Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ashraf Hotak

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Shah Ashraf Hotak (Pashto/Persian: شاه اشرف هوتک; died 1730), also known as Shah Ashraf Ghilji or Ghilzay (شاه اشرف غلجي), was an Afghan ruler who reigned as Shah of Iran from 1725 to 1729.

He was a member of the Hotak tribe of the Ghilji Pashtuns, who revolted against the declining Safavid dynasty of Iran and conquered the capital Isfahan in 1722. He was the son of Abdul Aziz Hotak and a nephew of Mirwais Hotak. He served as a commander in the army of his cousin Mahmud Hotak during the revolt against the Safavids. Ashraf also participated in the Battle of Gulnabad. In 1725, he killed his cousin and reigned as Shah of Iran until 1729. His reign was noted for the sudden decline in the Hotak tribal rule under increasing pressure from Ottoman, Russian, and Persian forces.[2]

Ashraf Khan halted both the Russian and Ottoman onslaughts. In the Ottoman–Hotaki War, he defeated the Ottoman Empire, which wanted to restore the Safavids to the throne, in a battle near Kermanshah. A peace agreement was finally signed in October 1727, in which Ashraf was recognized as Shah.

Ultimately, the royal Persian army of Shah Tahmasp II (one of the Shah Sultan Husayn's sons) under the leadership of Nader decisively defeated Ashraf's forces at the Battle of Damghan in October 1729 again at Murche-Khort the next year, causing the collapse of the Afghan army. Ashraf was killed on the way back to Kandahar, possibly on the orders of his cousin Hussain Hotak.

Biography

[edit]Ashraf was born in southern Afghanistan in the early 18th century into a prominent family of the Hotak tribe, which led the Ghilji (or Ghilzay) Pashtun confederacy along with the Tokhi tribe. He was the oldest son of Abdul Aziz Hotak and a nephew of Mirwais Hotak;[3] the latter was a mayor of Kandahar who revolted against the Safavids in 1709 and remained an independent ruler until 1715.[4] Ashraf participated in the invasion of Iran by the Ghilji in 1721–1722, which resulted in the siege and capture of the Safavid capital of Isfahan in 1722. The Safavid shah Soltan Hoseyn was overthrown and replaced by Ashraf's cousin, Mahmud, with whom Ashraf had poor relations.[3] After this, Ashraf returned to Kandahar and remained there for a few years.[4] In the meantime, Mahmud faced difficulties as ruler and grew increasingly unstable. His attitude towards Ashraf worsened, and the latter appeared to become more popular as Mahmud's position weakened.[5] Ashraf was convinced by his companions that he would be a better king than Mahmud. He returned to Isfahan and began plotting against his cousin.[4] Mahmud had Ashraf imprisoned, but on 22 April 1725 part of the Afghan army freed Ashraf and overthrew Mahmud, who was probably murdered shortly afterwards.[6] Ashraf was crowned as Shah of Iran on 26 April 1725.[3] After taking power, Ashraf eliminated a number of potential threats to his rule. He blinded his own brother and executed most of the leaders of the coup which had placed him on the throne. He also married a daughter of the deposed Soltan Hoseyn.[7] Historian Michael Axworthy writes that Ashraf was "as brutal and ruthless as Mahmud, but more calculating, less impulsive, and less prone to self-doubt."[8]

Ashraf spent most of his four-year-long reign in conflict with internal and external enemies. He sought to recover the territories which had recently been conquered by the Ottoman and Russian empires in the north and northwest of Iran. He initially attempted to come to a peaceful settlement with the Ottoman Empire and sent an embassy there in October 1725. He asked the Ottomans to acknowledge him as a legitimate and independent Sunni ruler. He argued that the Afghans had taken control of Iran as "unclaimed" territory, and that because Istanbul and Isfahan were located in non-contiguous regions, Iran need not be subordinated to the Ottomans. Ashraf's appeal was rebuffed by the Ottoman sultan Ahmed III, who ordered a campaign against the Afghans in the spring of 1726.[4] After the Ottoman commander Ahmed Pasha sent a letter to Ashraf stating his intention to restore the legitimate Iranian ruler, Ashraf ordered the execution of Soltan Hoseyn.[9] The Afghan and Ottoman armies met at Khorramabad in November 1726. The Afghans damaged Ottoman morale by sending infiltrators who emphasized the common Sunni faith of the two sides.[4] The Afghans emerged victorious, and a peace agreement was reached in October 1727 (but not ratified) which allowed the Ottomans to keep the Iranian lands they had occupied while recognizing Ashraf's rule. Ashraf then confronted the Russians. Although he suffered a defeat close to Langarud in 1727, he signed a treaty with the Russians at Rasht in February 1729 which further strengthened his legitimacy.[3]

Ashraf's struggle against the foreign invaders gained him some supporters among the Iranian population, especially among Sunni Kurds and Zoroastrians but also members of the Shi'ite Shahsevan tribe. However, most of the population still would not accept Afghan rule, and a number of rebellions broke out which weakened the government.[3] Additionally, the Afghans themselves suffered from internal divisions.[4] Ashraf could not count on the support of the Ghilji chiefs in Kandahar, who had supported his cousin Mahmud and were displeased with his overthrow.[8] Several individuals claiming Safavid descent raised rebellions in different parts of the country. After the defeat and death of these pretenders, only Tahmasp, Soltan Hoseyn's only living son who was sheltering in Mazandaran, was able to rally support and pose a serious threat to Ashraf's role. Tahmasp gained the support of many chiefs from the Qajar and Afshar tribes, two powerful Turkic tribes in the northeast of Iran. His most important military support came from Nader Qoli Beg Afshar (later Nader Shah). Tahmasp's forces captured Mashhad in November 1726 and eventually took control of all of northeastern Iran, whence they planned to take control of the throne.[3]

Ashraf sent a force against Tahmasp, which was defeated by Nader at Mehmandust near Damghan on 29 September 1729. Nader followed up on this victory and went on the offensive, forcing Ashraf to withdraw from his base in Tehran to Isfahan. In order to deter a pro-Safavid uprising in Isfahan, Afghan forces plundered the city and massacred part of its population. Apparently having received support from the Ottomans, Ashraf's army faced Nader's at Murche-Khort, 35 miles (56 km) northwest of Isfahan. The Afghans took large casualties in the fierce fighting, and Ashraf fled Isfahan on 13 November 1729, three days before Nader entered the city. Even after this defeat, however, Ashraf had an army of around 20,000. Nader chased after Ashraf and defeated his forces again at Zarqan and Pol-e Fasa, causing the collapse of the Afghan army. After a failed attempt to reach Ottoman Basra by sea, he made his way towards Kandahar through inland Iran. Near the border of Sistan, he was attacked by a group of Baluchis and killed in early 1730. The Baluchis may have been sent by Hussain, Ashraf's cousin, to avenge the killing of Mahmud.[3] According to another account, Hussain sent his own son Ibrahim after Ashraf after the latter reached Kandahar province. Ibrahim's men found Ashraf in a small village and chased after him on horseback. Ashraf stabbed Ibrahim in the side with a dagger, but Ibrahim was able to shoot Ashraf dead.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley Blackwell. p. 224. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Browne, Edward G. (1928). A Literary History of Persia. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 130–133.

- ^ a b c d e f g Balland, D. (1987). "Ašraf Ḡilzay". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/8: Aśoka IV–Āṯār al-Wozarāʾ (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. pp. 796–797. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Tucker, Ernest (2009). Fleet, K.; Krämer, G.; Matringe, D.; Nawas, J.; Stewart, D. J. (eds.). "Ashraf Ghilzay". Encyclopaedia of Islam Three Online. Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23011. Retrieved 14 April 2025.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris. p. 65. ISBN 978-1850437062.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 67.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 86.

- ^ a b Axworthy 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 88.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. 105.

Further reading

[edit]- Moreen, Vera B. (2010). "Ashraf, Shah". In Norman A. Stillman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Brill Online.

Ashraf Hotak

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Background

Family Origins and Parentage

Ashraf Hotak was born circa 1700 as the son of Abdul Aziz Hotak, a prominent figure in the Hotak clan of the Ghilzai Pashtun tribal confederation.[2] The Ghilzai, one of the largest Pashtun groups, traditionally inhabited regions including Ghazni, Qalati Ghilji, and southern Afghanistan, with tribal genealogies often linking their origins to a union between a Ghurid prince named Shah Husayn and a woman named Bibi Mato from the Lodi tribe.[3] The Hotak subtribe, to which Ashraf's family belonged, was centered in the Kandahar area, where members like his uncle Mirwais Hotak rose as local leaders under Safavid Persian administration in the early 18th century.[3] Abdul Aziz Hotak succeeded his brother Mirwais as governor of Kandahar following Mirwais's death on November 22, 1715, but his rule lasted only until February 1717, when he was killed by his nephew Mahmud Hotak, son of Mirwais, amid internal family rivalries over leadership.[4] This patricidal act underscored the contentious dynamics within the Hotak family, which had gained prominence through Mirwais's rebellion against Safavid governors in 1709, establishing de facto independence in the Loy Kandahar region. Ashraf, as Abdul Aziz's son, thus inherited a lineage tied to both entrepreneurial wealth—Mirwais had been a prosperous trader—and martial traditions of the Ghilzai nomads and herders who resisted Persian Shiite impositions while adhering to Sunni Islam.[4]Involvement in the Hotak Revolt Against Safavids

Ashraf Hotak, a Ghilji Pashtun from the Hotak clan and cousin to Mahmud Hotak, served as a military commander in the forces rebelling against Safavid authority. The broader Hotak revolt originated in 1709 when Mirwais Hotak, Ashraf's uncle, assassinated the Safavid governor Gurgin Khan in Kandahar and established de facto independence in southern Afghanistan, exploiting Safavid decline amid internal strife and religious tensions over imposed Shiism on the Sunni Ghilzais. Ashraf's direct involvement intensified under Mahmud Hotak, who succeeded Mirwais in 1715 and escalated the uprising into a full invasion of Persian territories starting in 1721, mobilizing around 18,000-20,000 Ghilji warriors to challenge Safavid control.[5] In the 1722 campaign, Ashraf commanded units during the advance on Isfahan, the Safavid capital. On March 8, 1722, he participated in the Battle of Gulnabad, where Hotak forces decisively defeated a numerically superior Safavid army—estimates ranging from 40,000 to over 100,000 troops—through effective use of mobility, feigned retreats, and exploitation of Persian disarray, resulting in heavy Safavid losses and minimal Hotak casualties. This victory, achieved despite the Afghans' smaller numbers, stemmed from Safavid military weaknesses including poor leadership, low morale, and logistical failures under Shah Sultan Husayn.[6][7] Following Gulnabad, Ashraf helped enforce the subsequent siege of Isfahan, which began in March 1722 and endured for six months amid severe famine that killed tens of thousands of civilians. His role in sustaining the blockade contributed to the city's capitulation on October 22, 1722, when Sultan Husayn surrendered the throne to Mahmud Hotak, marking the effective collapse of Safavid central authority and the Hotaks' temporary conquest of Persia. Ashraf's command experience in these operations highlighted the Ghilzai emphasis on tribal cohesion and guerrilla tactics over Safavid reliance on cumbersome levies.[8]Ascension to Power

The Death of Mahmud Hotak

Mahmud Hotak's mental state declined sharply after the fall of Isfahan in 1722, marked by paranoia that prompted the execution of numerous Persian nobles, ministers, and suspected conspirators, including mass slaughters under false pretenses.[7] This instability extended to his own kin; he blinded his son on allegations of treason and imprisoned his cousin Ashraf Hotak, suspecting disloyalty amid growing factionalism among Afghan leaders in Persia.[9] Historical accounts, primarily from Persian chroniclers antagonistic to the Hotak invaders, portray these actions as evidence of outright madness, though such depictions may reflect biased efforts to undermine Afghan legitimacy rather than purely objective reporting.[7] On April 22, 1725, a group of Afghan officers loyal to Ashraf orchestrated a palace coup in Isfahan, freeing him from confinement and deposing Mahmud.[10] [9] Mahmud died the same day, either from acute illness or murder—possibly by suffocation—three days after an initial confrontation, according to varying reports that highlight the ambiguity in contemporary records.[7] Ashraf Hotak promptly assumed the throne as shah, consolidating power by executing remaining rivals and framing his ascension as a necessary stabilization of the Hotak regime.[9] This transition ended Mahmud's brief three-year rule over Persia, shifting control to Ashraf amid ongoing threats from Safavid loyalists and emerging Persian warlords.[10]Initial Consolidation and Victory at Murche-Khort

Following the death of Mahmud Hotak on 25 April 1725, Ashraf Hotak seized power through a palace coup supported by dissident Afghan military officers who had grown disillusioned with Mahmud's erratic rule and mental instability.[11] Ashraf, previously confined by his cousin, was proclaimed shah on 26 April 1725, marking the beginning of his efforts to stabilize Hotak authority in Persia amid widespread resentment toward the Afghan occupiers and lingering Safavid loyalties.[12] To consolidate control, Ashraf focused on neutralizing internal threats, including Safavid restorationists in southern Persia who challenged Hotak dominance. He struck coins in his name to assert legitimacy as shah and pursued diplomatic outreach to neighboring powers, attempting negotiations with the Ottoman Empire to secure recognition and deter further encroachments on Persian territory.[11] A key measure was the execution of the deposed Safavid shah Sultan Husayn on 9 September 1726 (or 1727 per some accounts), ordered by Ashraf despite prior assurances of safety; this act, prompted by Husayn's alleged insulting correspondence with external actors, aimed to eradicate a symbolic focal point for opposition but alienated potential Persian allies.[7][12] Ashraf's early military actions further aided consolidation, as he repelled Ottoman advances into western Persia during the 1726–1727 conflict, defeating Turkish forces near Khoramabad and thereby securing Hotak holdings against external rivals seeking to exploit the power vacuum.) These victories temporarily bolstered his position, allowing him to maintain control over Isfahan and central Persia while addressing revolts in outlying regions. However, persistent Safavid loyalist movements and the rise of regional warlords like Nader Qoli Beg foreshadowed the fragility of his rule.Reign and Governance

Military Engagements and Defense of Territory

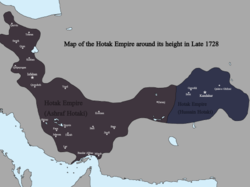

During his reign from 1725 to 1729, Ashraf Hotak focused on repelling Ottoman advances into western and northwestern Persia, where Ottoman forces had exploited the Safavid collapse to seize territories including Azerbaijan and Hamadan. In spring 1726, Ottoman offensives intensified, prompting Ashraf to dispatch an embassy in October 1725 seeking recognition as a Sunni sovereign, though this failed to avert conflict. Afghan forces achieved a notable victory at Khurramabad in November 1726, employing infiltrators to disrupt Ottoman lines and halt their momentum toward Isfahan.[11] This success enabled negotiations, culminating in the Treaty of Hamedan signed in October 1727, whereby the Ottomans formally recognized Ashraf as Shah of Persia while retaining their prior territorial gains from 1722–1724, such as parts of Azerbaijan, Hamadan, Kermanshah, and Lorestan. The agreement marked a temporary stabilization of Hotak control over central Persia, averting further Ottoman incursions despite Ashraf's demands for full restitution of annexed lands.[11] Ashraf also confronted Russian expansions in northern Persia, where Russian forces had occupied Caspian coastal regions following the 1722 Treaty of St. Petersburg with Safavid remnants. Hotak armies engaged Russian troops near Langarud in 1727, suffering a setback that limited immediate counteroffensives. Diplomatic efforts persisted, leading to an agreement at Rasht in February 1729, in which Russia acknowledged Ashraf's legitimacy as ruler, effectively checking further Russian probes into core Hotak-held territories without ceding additional ground.[11] These engagements demonstrated Ashraf's tactical acumen in leveraging guerrilla-style infiltrations and selective battles to defend the Hotak empire's extent, as depicted in contemporary maps of 1728 showing control over central Iran amid encirclement by Ottoman, Russian, and Uzbek pressures. However, the treaties conceded peripheral regions, reflecting the dynasty's overextension and reliance on fragile alliances rather than decisive conquests.[7]Diplomatic Relations and External Pressures

Upon assuming power in October 1725, Ashraf Hotak prioritized diplomatic engagement with the Ottoman Empire to secure legitimacy for his rule over Persia, dispatching an embassy that October to negotiate recognition and avert conflict over contested western territories.[13] Tensions escalated into the Ottoman-Hotaki War (1726–1727), during which Ottoman forces advanced into northwestern Iran, but Ashraf's military resistance stalled their progress, prompting negotiations. The resulting Treaty of Hamedan, signed in October 1727, marked a significant diplomatic achievement for Ashraf: the Ottoman Sultan, as Caliph, formally acknowledged him as the legitimate Shah of Persia, conferring Islamic legitimacy on his regime in exchange for Hotak confirmation of Ottoman sovereignty over western and northwestern Iranian provinces, including Azerbaijan, Hamadan, Kermanshah, Lorestan, and related districts.[13] This arrangement temporarily stabilized the western frontier, allowing Ashraf to redirect resources eastward, though it effectively partitioned Persia and highlighted the opportunistic territorial gains by neighboring powers amid Safavid collapse. Concurrent external pressures emanated from Russian forces, who had occupied Caspian coastal regions (such as Derbent, Baku, and Astrabad) following their 1723 treaty with the crumbling Safavid regime. Ashraf mounted a campaign against these holdings in 1727, achieving initial successes but ultimately suffering a reversal near Langarud; by February 1729, he concluded a treaty at Rasht that ratified Russian control over the northern provinces to forestall further incursions.[13] These concessions underscored the multifaceted threats to Hotak authority, as Russian expansionism compounded Ottoman ambitions and internal Persian resistance, eroding Ashraf's capacity to maintain centralized control despite his diplomatic maneuvers. No formal alliances or treaties with the Mughal Empire are recorded during his reign, though Hotak control over eastern territories like Kandahar indirectly checked Mughal influence in the region without direct negotiation.[13]Administrative Measures and Internal Policies

Ashraf Hotak sought to stabilize governance in Persia following his ascension, issuing a key reconciliatory edict in Ẕu ol-Qaʿdeh 1138 AH (July 1726) directed at the residents of Isfahan, the Hotak capital.[14] This document, styled as a "charter of justice" (manshur ol-ʿedāleh), prohibited Afghan warriors from committing violence or seizing property from local inhabitants, regulated intermarriages between Afghans and Persians, and pledged equitable administration of justice to foster coexistence.[14] Aimed primarily at bridging tensions between the Sunni Afghan occupiers and the Shiʿi Persian population—exacerbated by the prior siege of Isfahan—the edict represented an effort to legitimize Hotak authority, mitigate resentment, and restore basic order amid economic distress and factional strife.[14] To support administrative continuity, Ashraf commissioned the Taẕkerat ol-Moluk in the mid-1720s, a manual outlining protocols for state administration that drew on Persian bureaucratic traditions.[14] In 1139 AH (1727), he requested archival diplomatic correspondence from the Ottoman Empire to revive the functions of the Safavid Secretariat, indicating an intent to maintain Persia’s external administrative apparatus despite the dynastic rupture.[14] Internally, the chancellery incorporated Sunni officials from Darjazin alongside residual Safavid personnel, blending Afghan tribal elements with established Persian clerical expertise to handle decrees and seals.[14] Ashraf further bolstered legitimacy through Persianate regnal titles evoking historical rulers like Anushirvan and invocations of Qurʾanic authority on seals, which affirmed his Sunni orientation while appealing to broader imperial precedents.[14] These measures reflected pragmatic adaptation to ruling a diverse, war-torn empire, prioritizing short-term pacification over sweeping reforms amid persistent revolts and fiscal collapse in Isfahan.[14] However, the brevity of Ashraf's reign—ending in 1729—and mounting external pressures limited implementation, with administrative efforts overshadowed by military imperatives and local non-compliance.[14]Downfall and Defeat

Rise of Nader Shah Afshar

Nader Shah Afshar, born in November 1688 in Darra Gaz near Khorasan to a family of the Qirqlu clan of the Afshar Turkmen tribe, emerged as a military leader amid the collapse of Safavid authority following the Hotak Afghan conquest of Isfahan in 1722.[15] Initially based in Abivard north of Mashhad, he allied with local Afshar ruler Baba Ali Beg and gained prominence through tribal warfare and defense against incursions, leveraging his skills in pastoral Turkmen warfare traditions.[15] In the mid-1720s, as regional warlords proliferated in the power vacuum, Nader distinguished himself by defeating Malek Mahmud Sistani, a claimant to Saffarid lineage who controlled parts of Sistan and had terrorized Khorasan; this victory, achieved through superior tactics and mobilization of Afshar and other Turkmen forces, solidified his reputation and expanded his influence over local tribes.[15] By late 1726, he recaptured Mashhad from minor Afghan garrisons and Afghan-aligned factions, establishing a base for further consolidation in Khorasan while suppressing rebellions among Turkic and Kurdish tribes, thereby securing the province's loyalty and resources for larger campaigns.[16] [9] Seeking legitimacy beyond tribal authority, Nader allied with Tahmasp Mirza, son of the deposed Safavid shah Sultan Husayn, in Qazvin around 1726, receiving the title Tahmasp-qoli Khan and command of Safavid loyalist forces as qurchi-bashi (imperial guards commander).[15] Under this nominal Safavid banner, he extended control to Sistan, Kerman, and Mazandaran by 1728, integrating diverse levies including Turkmen cavalry and Persian infantry, which numbered in the tens of thousands by estimates from contemporary accounts, positioning his forces as the primary counterweight to Hotak dominance in central Persia.[17] In early 1729, Nader turned eastward to neutralize threats from Abdali Afghan tribes raiding Khorasan, defeating them near Herat in May and incorporating some contingents into his army, which enhanced his mobility and intelligence on Hotak movements.[16] This series of victories transformed Nader from a regional chieftain into the de facto restorer of Persian sovereignty in the east, drawing defectors from Hotak garrisons disillusioned with Ashraf Hotak's overstretched rule and Ottoman encroachments, setting the stage for a direct challenge to Afghan control over the Iranian plateau.[15]Battle of Damghan and Collapse of Hotak Control

In September 1729, Ashraf Hotak dispatched an army to intercept Nader, who was advancing from Khorasan with Shah Tahmasp II to reclaim Persian territories from Hotak control. The two forces clashed at the Battle of Damghan on 29 September 1729 (6th Rabi' I 1142 AH), near the village of Mehmandust outside Damghan.[18] Nader commanded approximately 25,000 troops, while Ashraf fielded a larger force estimated at 40,000 to 50,000 men.[18] Nader deployed his army in a compact formation, with musketeers and artillery positioned to encircle the main body, withholding fire until Ashraf's charging divisions closed to musket range. The Hotak forces advanced in three divisions targeting Nader's center and flanks, but sustained heavy losses from Persian artillery that targeted and destroyed Afghan zanbūrak camel-mounted swivel guns. The death of the Afghan standard-bearer triggered a rout among Ashraf's troops, resulting in approximately 12,000 Hotak casualties compared to 4,000 on the Persian side. Nader's forces, though victorious, did not pursue aggressively due to their relative inexperience.[18] The defeat at Damghan shattered Hotak military cohesion in northern and central Persia. Ashraf retreated westward to Varamin and then Isfahan, his capital, but faced mounting desertions and inability to regroup effectively. Nader pressed the advantage, advancing southward and liberating key regions from Hotak garrisons through subsequent engagements, including victories at Murchakhur and Zarqan by early 1730.[18] Ashraf ultimately abandoned Isfahan in December 1729 without further major resistance, fleeing eastward toward Shiraz and eventually into Afghanistan, thereby relinquishing control over the Persian heartland.[18] This collapse confined Hotak authority to peripheral strongholds in southern Afghanistan, particularly Kandahar, where Ashraf's cousin Hussain Hotak maintained resistance until Nader's siege and conquest in 1738. The rapid unraveling of Hotak dominion in Persia stemmed from Nader's tactical acumen, superior discipline, and exploitation of ethnic and sectarian divisions among Hotak levies, many of whom were non-Afghan auxiliaries alienated by Ghilzai dominance. By restoring Tahmasp II to Isfahan, Nader effectively ended the seven-year Afghan interregnum, though he would later supplant the Safavids himself in 1736.[18]Death and Immediate Aftermath

Flight and Assassination

Following his decisive defeat by Nader Shah at the Battle of Damghan on October 29, 1729, Ashraf Hotak withdrew his forces southward, but Nader's relentless pursuit led to further Afghan losses at the Battle of Murche Khort on November 11, 1729, prompting Ashraf to evacuate Isfahan and flee toward his Ghilzai strongholds in southern Afghanistan. Nader continued the chase, culminating in the Battle of Zarghan near Farah on January 15, 1730, where Ashraf's army of approximately 10,000–20,000 was routed by Nader's 20,000–30,000 Persians, resulting in heavy Afghan casualties and the collapse of Hotak authority in Persia. With his military position untenable, Ashraf escaped the battlefield with remnants of his forces, directing his flight through the arid regions of Sistan and into Balochistan en route to Kandahar.[19] During this retreat in early 1730, Ashraf was intercepted and captured by Mir Mohabbat Khan Baloch, the Khan of Kalat, a local Baloch ruler whose territory lay across the escape path. Mir Mohabbat Khan executed Ashraf, effectively ending the Hotak interregnum in Persia and eliminating Ashraf as a contender for regional power. Some accounts suggest the killing stemmed from tribal rivalries or opportunistic seizure of Ashraf's remaining treasury and followers, though primary contemporary records are sparse and the precise motive remains unverified beyond Baloch agency in the assassination.[20][21]Succession Within the Hotak Dynasty

Following Ashraf Hotak's defeat at the Battle of Damghan in October 1729 and his subsequent assassination in early 1730 while fleeing toward Afghanistan, Hussain Hotak—Ashraf's cousin and a prominent Ghilzai leader—emerged as the effective head of the remaining Hotak domains centered in Kandahar.[22][23] Hussain had already been administering Kandahar and surrounding territories in southern Afghanistan during Ashraf's tenure over Persia, providing a base of tribal support independent of the Persian campaigns.[19] This arrangement reflected the decentralized nature of Hotak authority, where familial and tribal loyalties sustained control amid the dynasty's overextension.[22] Hussain's rule from 1729 to 1738 marked the final phase of Hotak governance, confined primarily to Kandahar and parts of Qandahar province, as Persian territories were reclaimed by Nader Shah Afshar.[19] He fortified defenses against encroaching Persian forces, leveraging local Ghilzai alliances and the rugged terrain to resist incursions for nearly a decade.[23] No significant internal challenges to Hussain's succession are recorded, likely due to his prior role in the dynasty's eastern strongholds and the absence of viable rivals following Ashraf's demise; some accounts suggest Hussain may have influenced the circumstances of Ashraf's death to consolidate power and avenge prior familial disputes, such as Ashraf's seizure of the throne from Mahmud Hotak in 1725.[24][22] The dynasty's end came in 1738 after Nader Shah's prolonged siege of Kandahar, which lasted over two years and involved encircling the city with trenches and blockades to starve out defenders.[25] Hussain surrendered in mid-1738, leading to the Hotak loss of their last stronghold; he was subsequently exiled to Mazandaran in northern Persia, where he died in captivity.[23] This defeat extinguished organized Hotak resistance, fragmenting Ghilzai tribal power and paving the way for Nader Shah's reconsolidation of Persian authority over former Safavid lands, including Afghanistan.[19]Legacy and Historical Assessment

Long-Term Impact on Persia and Afghanistan

The Hotak occupation of Persia, culminating under Ashraf's rule from 1725 to 1729, inflicted severe devastation on key urban centers like Isfahan, where a six-month siege in 1722 caused widespread famine, disease, and an estimated 80,000 civilian deaths, drastically reducing the city's population from around 600,000 and leaving many buildings in ruins.[26][27] This economic and demographic collapse eroded Persia's administrative infrastructure, with brutal taxation under Hotak governance sparking rebellions and further instability, preventing any meaningful recovery of Safavid authority.[7] The resulting power vacuum facilitated the rise of Nader Shah Afshar, who defeated Ashraf at the Battle of Damghan on October 29, 1729, expelled the Hotaks by 1730, and transitioned from restoring puppet Safavid rulers to founding the Afsharid dynasty in 1736, shifting Persian governance toward aggressive militarism and territorial reconquest.[7] In the longer term, the Hotak interlude marked the irreversible decline of centralized Safavid cosmopolitanism, contributing to a fragmented political landscape that persisted through the Afsharid and subsequent Zand periods until the Qajar consolidation in the late 18th century, with Isfahan permanently losing its status as the empire's cultural and economic hub.[26] The era's anarchy also invited opportunistic annexations by Ottomans and Russians, weakening Persia's borders and necessitating Nader's expansive campaigns to reclaim lost territories, though his regime's brutality sowed seeds for further instability after his assassination in 1747.[7] For Afghanistan, Ashraf's branch of the Hotak dynasty represented a high-water mark of Ghilji Pashtun expansion, but its collapse after Nader's siege of Kandahar in 1738—achieved with aid from rival Abdali tribes—exposed internal divisions that undermined sustained unity.[7] This fragmentation, rooted in tribal rivalries between Ghilji Hotaks and Abdali/Durrani factions, cleared the path for Ahmad Shah Durrani's election as leader in 1747, founding the Durrani Empire and establishing the first enduring Afghan state that unified Pashtun territories and resisted Persian reconquest.[28] The Hotak legacy thus fostered a precedent for Afghan independence from Persian domination, originating with Mirwais Hotak's 1709 revolt, but ultimately yielded to Durrani hegemony, shaping enduring ethnic and political dynamics in the region.[28]Evaluations of Achievements and Failures

Ashraf Hotak's achievements primarily lie in diplomatic maneuvering and temporary military successes that briefly stabilized Hotak control over central Persia following the instability of his predecessor Mahmud Hotak. In 1726–1727, during the Ottoman–Hotaki War, Hotak forces under Ashraf's command defeated an Ottoman army near Kermanshah, preventing further incursions toward Isfahan and demonstrating tactical effectiveness against a numerically superior foe.[29] This victory facilitated the Treaty of Hamedan in October 1727, in which the Ottoman Empire recognized Ashraf as Shah of Persia, affirming Hotak sovereignty over core Iranian territories while conceding western provinces such as Azerbaijan and Hamadan to Ottoman control.[30] Such recognition provided a measure of international legitimacy to the Hotak regime, which had seized power through the 1722 conquest of Isfahan from the Safavids. However, these gains were undermined by critical failures in governance and strategic foresight. Ashraf's execution of the deposed Safavid Shah Sultan Husayn in 1725, despite oaths guaranteeing his safety, eroded legitimacy among Persian elites and intensified Safavid restorationist movements, alienating potential administrative collaborators reliant on traditional loyalties.[7] Internally, his rule struggled with factionalism within the Ghilzai Pashtun tribal confederation, limiting effective administration and revenue collection across the vast territory nominally under Hotak sway, as evidenced by persistent rebellions in provinces like Khorasan.[9] Militarily, Ashraf's overextension became evident in 1729 against the resurgent Persian forces led by Nader Qoli Beg. Despite initial defenses, Hotak armies suffered catastrophic defeats at the Battle of Damghan on October 12, 1729, and subsequent engagements, resulting in the collapse of Hotak dominance in Persia and Ashraf's flight to Kandahar.[19] Historians attribute this downfall to Ashraf's failure to forge a cohesive imperial structure beyond tribal alliances, contrasting with Nader's ability to integrate diverse Persian factions, and to underestimating the motivational force of Safavid symbolism in rallying opposition.[29] Overall, while Ashraf extended the Hotak interregnum through adroit short-term diplomacy, his regime's reliance on conquest without institutional adaptation precluded enduring achievements, marking it as a transient disruption rather than a viable alternative to Safavid or subsequent Afsharid governance.