Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

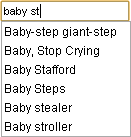

Autocomplete

View on Wikipedia

baby st being autocompleted to various optionsAutocomplete, or word completion, is a feature in which an application predicts the rest of a word a user is typing. In Android and iOS[1] smartphones, this is called predictive text. In graphical user interfaces, users can typically press the tab key to accept a suggestion or the down arrow key to accept one of several.

Autocomplete speeds up human-computer interactions when it correctly predicts the word a user intends to enter after only a few characters have been typed into a text input field. It works best in domains with a limited number of possible words (such as in command line interpreters), when some words are much more common (such as when addressing an e-mail), or writing structured and predictable text (as in source code editors).

Many autocomplete algorithms learn new words after the user has written them a few times, and can suggest alternatives based on the learned habits of the individual user.

Definition

[edit]Original purpose

[edit]The original purpose of word prediction software was to help people with physical disabilities increase their typing speed,[2] as well as to help them decrease the number of keystrokes needed in order to complete a word or a sentence.[3] The need to increase speed is noted by the fact that people who use speech-generating devices generally produce speech at a rate that is less than 10% as fast as people who use oral speech.[4] But the function is also very useful for anybody who writes text, particularly people–such as medical doctors–who frequently use long, hard-to-spell terminology that may be technical or medical in nature.

Description

[edit]Autocomplete or word completion works so that when the writer writes the first letter or letters of a word, the program predicts one or more possible words as choices. If the intended word is included in the list, the writer can select it, for example, by using the number keys. If the word that the user wants is not predicted, the writer must enter the next letter of the word. At this time, the word choice(s) is altered so that the words provided begin with the same letters as those that have been selected. When the word that the user wants appears it is selected, and the word is inserted into the text.[5][6] In another form of word prediction, words most likely to follow the just written one are predicted, based on recent word pairs used.[6] Word prediction uses language modeling, where within a set vocabulary the words are most likely to occur are calculated.[7] Along with language modeling, basic word prediction on AAC devices is often coupled with a frecency model, where words the AAC user has used recently and frequently are more likely to be predicted.[4] Word prediction software often also allows the user to enter their own words into the word prediction dictionaries either directly, or by "learning" words that have been written.[5][6] Some search returns related to genitals or other vulgar terms are often omitted from autocompletion technologies, as are morbid terms[8][9]

History

[edit]The autocomplete and predictive text technology was invented by Chinese scientists and linguists in the 1950s to solve the input inefficiency of the Chinese typewriter,[10] as the typing process involved finding and selecting thousands of logographic characters on a tray,[11] drastically slowing down the word processing speed.[12][13]

In the 1950s, typists came to rearrange the character layout from the standard dictionary layout to groups of common words and phrases.[14] Chinese typewriter engineers innovated mechanisms to access common characters accessible at the fastest speed possible by word prediction, a technique used today in Chinese input methods for computers, and in text messaging in many languages. According to Stanford University historian Thomas Mullaney, the development of modern Chinese typewriters from the 1960s to 1970s influenced the development of modern computer word processors and affected the development of computers themselves.[15][11][14]

Types of autocomplete tools

[edit]There are standalone tools that add autocomplete functionality to existing applications. These programs monitor user keystrokes and suggest a list of words based on first typed letter(s). Examples are Typingaid and Letmetype.[16][17] LetMeType, freeware, is no longer developed, the author has published the source code and allows anybody to continue development. Typingaid, also freeware, is actively developed. Intellicomplete, both a freeware and payware version, works only in certain programs which hook into the intellicomplete server program.[18] Many Autocomplete programs can also be used to create a Shorthand list. The original autocomplete software was Smartype, which dates back to the late 1980s and is still available today. It was initially developed for medical transcriptionists working in WordPerfect for MS/DOS, but it now functions for any application in any Windows or Web-based program.

Shorthand

[edit]Shorthand, also called Autoreplace, is a related feature that involves automatic replacement of a particular string with another one, usually one that is longer and harder to type, such as "myname" with "Lee John Nikolai François Al Rahman". This can also quietly fix simple typing errors, such as turning "teh" into "the". Several Autocomplete programs, standalone or integrated in text editors, based on word lists, also include a shorthand function for often used phrases.[citation needed]

Context completion

[edit]Context completion is a text editor feature, similar to word completion, which completes words (or entire phrases) based on the current context and context of other similar words within the same document, or within some training data set. The main advantage of context completion is the ability to predict anticipated words more precisely and even with no initial letters. The main disadvantage is the need of a training data set, which is typically larger for context completion than for simpler word completion. Most common use of context completion is seen in advanced programming language editors and IDEs, where training data set is inherently available and context completion makes more sense to the user than broad word completion would.[citation needed]

Line completion is a type of context completion, first introduced by Juraj Simlovic in TED Notepad, in July 2006. The context in line completion is the current line, while the current document poses as a training data set. When the user begins a line that starts with a frequently used phrase, the editor automatically completes it, up to the position where similar lines differ, or proposes a list of common continuations.[citation needed]

Action completion in applications are standalone tools that add autocomplete functionality to existing applications or all existing applications of an OS, based on the current context. The main advantage of Action completion is the ability to predict anticipated actions. The main disadvantage is the need of a data set. Most common use of Action completion is seen in advanced programming language editors and IDEs. But there are also action completion tools that work globally, in parallel, across all applications of the entire PC without (very) hindering the action completion of the respective applications.[citation needed]

Software integration

[edit]In web browsers

[edit]

In web browsers, autocomplete is done in the address bar (using items from the browser's history) and in text boxes on frequently used pages, such as a search engine's search box. Autocomplete for web addresses is particularly convenient because the full addresses are often long and difficult to type correctly.

In web forms

[edit]Autocompletion or "autofill" is frequently found in web browsers, used to fill in web forms automatically. When a user inputs data into a form and subsequently submits it, the web browser will often save the form's contents by default.[citation needed]

This feature is commonly used to fill in login credentials. However, when a password field is detected, the web browser will typically ask the user for explicit confirmation before saving the password in its password store, often secured with a built-in password manager to allow the use of a "master password" before credentials can be autofilled.[19]

Most of the time, such as in Internet Explorer and Google Toolbar, the entries depend on the form field's name, so as to not enter street names in a last name field or vice versa. For this use, proposed names for such form fields, in earlier HTML 5 specifications this RFC is no longer referenced, thus leaving the selection of names up to each browser's implementation.

Certain web browsers such as Opera automatically autofill credit card information and addresses.[20]

An individual webpage may enable or disable browser autofill by default. This is done in HTML with the autocomplete attribute in a <form> element or its corresponding form elements.

<!-- Autocomplete turned on by default -->

<form autocomplete="on">

<!-- This form element has autocomplete turned on -->

<input name="username" autocomplete="on">

<!-- While this one inherits its parent form's value -->

<input name="password" type="password">

</form>

It has been shown that the autofill feature of modern browsers can be exploited in a phishing attack with the use of hidden form fields, which allows personal information such as the user's phone number to be collected.[21]

HTML has a datalist element that can be used to feed an input element with autcompletions.[22]

<label for="ice-cream-choice">Choose a flavor:</label>

<input list="ice-cream-flavors" id="ice-cream-choice" name="ice-cream-choice" />

<datalist id="ice-cream-flavors">

<option value="Chocolate"></option>

<option value="Coconut"></option>

<option value="Mint"></option>

<option value="Strawberry"></option>

<option value="Vanilla"></option>

</datalist>

In e-mail programs

[edit]In e-mail programs autocomplete is typically used to fill in the e-mail addresses of the intended recipients. Generally, there are a small number of frequently used e-mail addresses, hence it is relatively easy to use autocomplete to select among them. Like web addresses, e-mail addresses are often long, hence typing them completely is inconvenient.[citation needed]

For instance, Microsoft Outlook Express will find addresses based on the name that is used in the address book. Google's Gmail will find addresses by any string that occurs in the address or stored name.[citation needed]

In retail and ecommerce websites

[edit]Autocomplete, often called predictive search, is used to suggest relevant products, categories, or queries as a shopper types into the search bar. This feature helps reduce typing effort and guides users toward popular or high-converting search terms. Many ecommerce systems generate these suggestions dynamically, based on recent search data or trending products, to improve both speed and discoverability. [23]

In search engines

[edit]In search engines, autocomplete user interface features provide users with suggested queries or results as they type their query in the search box. This is also commonly called autosuggest or incremental search. This type of search often relies on matching algorithms that forgive entry errors such as phonetic Soundex algorithms or the language independent Levenshtein algorithm. The challenge remains to search large indices or popular query lists in under a few milliseconds so that the user sees results pop up while typing.

Autocomplete can have an adverse effect on individuals and businesses when negative search terms are suggested when a search takes place. Autocomplete has now become a part of reputation management as companies linked to negative search terms such as scam, complaints and fraud seek to alter the results. Google in particular have listed some of the aspects that affect how their algorithm works, but this is an area that is open to manipulation.[24]

In source code editors

[edit]

Autocompletion of source code is also known as code completion. In a source code editor, autocomplete is greatly simplified by the regular structure of the programming language. There are usually only a limited number of words meaningful in the current context or namespace, such as names of variables and functions. An example of code completion is Microsoft's IntelliSense design. It involves showing a pop-up list of possible completions for the current input prefix to allow the user to choose the right one. This is particularly useful in object-oriented programming because often the programmer will not know exactly what members a particular class has. Therefore, autocomplete then serves as a form of convenient documentation as well as an input method.

Another beneficial feature of autocomplete for source code is that it encourages the programmer to use longer, more descriptive variable names, hence making the source code more readable. Typing large words which may contain camel case like numberOfWordsPerParagraph can be difficult, but autocomplete allows a programmer to complete typing the word using a fraction of the keystrokes.

In database query tools

[edit]Autocompletion in database query tools allows the user to autocomplete the table names in an SQL statement and column names of the tables referenced in the SQL statement. As text is typed into the editor, the context of the cursor within the SQL statement provides an indication of whether the user needs a table completion or a table column completion. The table completion provides a list of tables available in the database server the user is connected to. The column completion provides a list of columns for only tables referenced in the SQL statement. SQL Server Management Studio provides autocomplete in query tools.[citation needed]

In word processors

[edit]In many word processing programs, autocompletion decreases the amount of time spent typing repetitive words and phrases. The source material for autocompletion is either gathered from the rest of the current document or from a list of common words defined by the user. Currently Apache OpenOffice, Calligra Suite, KOffice, LibreOffice and Microsoft Office include support for this kind of autocompletion, as do advanced text editors such as Emacs and Vim.

- Apache OpenOffice Writer and LibreOffice Writer have a working word completion program that proposes words previously typed in the text, rather than from the whole dictionary

- Microsoft Excel spreadsheet application has a working word completion program that proposes words previously typed in upper cells

In command-line interpreters

[edit]

In a command-line interpreter, such as Unix's sh or bash, or Windows's cmd.exe or PowerShell, or in similar command line interfaces, autocomplete of command names and file names may be accomplished by keeping track of all the possible names of things the user may access. Here autocomplete is usually done by pressing the Tab ↹ key after typing the first several letters of the word. For example, if the only file in the current directory that starts with x is xLongFileName, the user may prefer to type x and autocomplete to the complete name. If there were another file name or command starting with x in the same scope, the user would type more letters or press the Tab key repeatedly to select the appropriate text.

Efficiency

[edit]Research

[edit]Although research has shown that word prediction software does decrease the number of keystrokes needed and improves the written productivity of children with disabilities,[2] there are mixed results as to whether or not word prediction actually increases speed of output.[25][26] It is thought that the reason why word prediction does not always increase the rate of text entry is because of the increased cognitive load and requirement to move eye gaze from the keyboard to the monitor.[2]

In order to reduce this cognitive load, parameters such as reducing the list to five likely words, and having a vertical layout of those words may be used.[2] The vertical layout is meant to keep head and eye movements to a minimum, and also gives additional visual cues because the word length becomes apparent.[27] Although many software developers believe that if the word prediction list follows the cursor, that this will reduce eye movements,[2] in a study of children with spina bifida by Tam, Reid, O'Keefe & Nauman (2002) it was shown that typing was more accurate, and that the children also preferred when the list appeared at the bottom edge of the screen, at the midline. Several studies have found that word prediction performance and satisfaction increases when the word list is closer to the keyboard, because of the decreased amount of eye-movements needed.[28]

Software with word prediction is produced by multiple manufacturers. The software can be bought as an add-on to common programs such as Microsoft Word (for example, WordQ+SpeakQ, Typing Assistant,[29] Co:Writer,[citation needed] Wivik,[citation needed] Ghotit Dyslexia),[citation needed] or as one of many features on an AAC device (PRC's Pathfinder,[citation needed] Dynavox Systems,[citation needed] Saltillo's ChatPC products[citation needed]). Some well known programs: Intellicomplete,[citation needed] which is available in both a freeware and a payware version, but works only with programs which are made to work with it. Letmetype[citation needed] and Typingaid[citation needed] are both freeware programs which work in any text editor.

An early version of autocompletion was described in 1967 by H. Christopher Longuet-Higgins in his Computer-Assisted Typewriter (CAT),[30] "such words as 'BEGIN' or 'PROCEDURE' or identifiers introduced by the programmer, would be automatically completed by the CAT after the programmer had typed only one or two symbols."

See also

[edit]- Autocorrection – Feature on word processors to automatically correct misspelled words, automatic correction of misspelled words.

- Autofill – Computing feature predicting ending to a word a user is typing

- Combo box – User interface element

- Context-sensitive user interface – Concept in human-computer interaction

- GitHub Copilot – Artificial intelligence tool

- Google Feud – Website game

- Incremental search – User interface method to search for text

- OpenSearch (specification) – Protocols for syndicating search results

- Predictive text – Input technology for mobile phone keypads

- Qwerty effect – Effects of computer keyboard layout on language and behavior

- Search suggest drop-down list – Query feature used in computing

- Snippet – Small amount of source code used for productivity

References

[edit]- ^ "How to use Auto-Correction and predictive text on your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch". Apple Support. Apple.

- ^ a b c d e Tam, Cynthia; Wells, David (2009). "Evaluating the Benefits of Displaying Word Prediction Lists on a Personal Digital Assistant at the Keyboard Level". Assistive Technology. 21 (3): 105–114. doi:10.1080/10400430903175473. PMID 19908678. S2CID 23183632.

- ^ Anson, D.; Moist, P.; Przywara, M.; Wells, H.; Saylor, H.; Maxime, H. (2006). "The Effects of Word Completion and Word Prediction on Typing Rates Using On-Screen Keyboards". Assistive Technology. 18 (2): 146–154. doi:10.1080/10400435.2006.10131913. PMID 17236473. S2CID 11193172.

- ^ a b Trnka, K.; Yarrington, J.M.; McCoy, K.F. (2007). "The Effects of Word Prediction on Communication Rate for AAC". NAACL-Short '07: Human Language Technologies 2007: The Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Vol. Companion Volume, Short Papers. Association for Computational Linguistics. pp. 173–6. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.363.2416.

- ^ a b Beukelman, D.R.; Mirenda, P. (2005). Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. p. 77. ISBN 9781557666840. OCLC 254228982.

- ^ a b c Witten, I.H.; Darragh, John J. (1992). The reactive keyboard. Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-521-40375-7.

- ^ Jelinek, F. (1990). "Self-Organized Language Modeling for Speech Recognition". In Waibel, A.; Lee, Kai-Fu (eds.). Readings in Speech Recognition. Morgan Kaufmann. p. 450. ISBN 9781558601246.

- ^ Oster, Jan (2015). "Communication, defamation and liability of intermediaries". Legal Studies. 35 (2): 348–368. doi:10.1111/lest.12064. S2CID 143005665.

- ^ McCulloch, Gretchen (11 February 2019). "Autocomplete Presents the Best Version of You". Wired. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Mcclure, Max (12 November 2012). "Chinese typewriter anticipated predictive text, finds historian".

- ^ a b Sorrel, Charlie (February 23, 2009). "How it Works: The Chinese Typewriter". Wired.

- ^ Greenwood, Veronique (14 December 2016). "Why predictive text is making you forget how to write". New Scientist.

- ^ O'Donovan, Caroline (16 August 2016). "How This Decades-Old Technology Ushered In Predictive Text". Buzzfeed.

- ^ a b Mullaney, Thomas S. (2018-07-16). "90,000 Characters on 1 Keyboard". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Featured Research – world's first history of the Chinese typewriter, Humanities at Stanford, January 2, 2010

- ^ "[AHK 1.1]TypingAid v2.22.0 — Word AutoCompletion Utility". AutoHotkey. 2010.

- ^ Clasohm, Carsten (2011). "LetMeType". Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2012-05-09.

- ^ "Medical Transcription Software — IntelliComplete". FlashPeak. 2014.

- ^ "Password Manager - Remember, delete and edit logins and passwords in Firefox". Firefox Support.

- ^ "Autofill: What web devs should know, but don't". Cloud Four. 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Browser Autofill Profiles Can Be Abused for Phishing Attacks". Bleeping Computer.

- ^ ": The HTML Data List element - HTML | MDN". developer.mozilla.org. 9 July 2025. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ Hearst, Marti A. (2009). Search user interfaces. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11379-3.

- ^ Davids, Neil (2015-06-03). "Changing Autocomplete Search Suggestions". Reputation Station. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Dabbagh, H.H.; Damper, R.I. (1985). "Average Selection Length and Time as Predictors of Communication Rate". In Brubaker, C.; Hobson, D.A. (eds.). Technology, a Bridge to Independence: Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology, Memphis, Tennessee, June 24–28th, 1985. Rehabilitation Engineering Society of North America. pp. 404–6. OCLC 15055289. 80177b42-e668-4ed5-a256-49b9440bdfa5.

- ^ Goodenough-Trepagnier, C.; Rosen, M.J. (1988). "Predictive Assessment for Communication Aid Prescription: Motor-Determined Maximum Communication Rate". In Bernstein, L.E. (ed.). The vocally impaired: Clinical Practice and Research. Philadelphia: Grune & Stratton. pp. 165–185. ISBN 9780808919087. OCLC 567938402. as cited in Tam & Wells 2009

- ^ Swiffin, A.L.; Arnott, J.L.; Pickering, J.A.; Newell, A.F. (1987). "Adaptive and predictive techniques in a communication prosthesis". Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 3 (4): 181–191. doi:10.1080/07434618712331274499. as cited in Tam & Wells 2009

- ^ Tam, C.; Reid, D.; Naumann, S.; O'Keefe, B. (2002). "Perceived benefits of word prediction intervention on written productivity in children with spina bifida and hydrocephalus". Occupational Therapy International. 9 (3): 237–255. doi:10.1002/oti.167. PMID 12374999. as cited in Tam & Wells 2009.

- ^ Sumit Software (2010). "Typing Assistant – New generation of word prediction software". PRLog: Press Release Distribution.

- ^ Longuet-Higgins, H.C.; Ortony, A. (1968). "The Adaptive Memorization of Sequences". Machine Intelligence 3, Proceedings of the Third Annual Machine Intelligence Workshop, University of Edinburgh, September 1967. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 311–322.

External links

[edit]- Live Search Explained—Examples and explanations of working web examples plus a discussion of the usability benefits compared to traditional search.

- Google Feud—The first and most popular of many games built using autocomplete data, which won a Webby Award for "Best Game" in 2016.

- Mimicking Google's Search Autocomplete With a Single MigratoryData Server—Optimize search autocomplete using persistent WebSocket connections to achieve both low-latency search experience and bandwidth improvement.

Autocomplete

View on GrokipediaDefinition

Core Concept

Autocomplete is a user interface feature that provides predictive suggestions to complete partial user inputs in real-time, thereby enhancing typing efficiency and reducing cognitive load during data entry or search tasks.[10] As users enter characters into an input field, such as a text box or search bar, the system generates and displays possible completions based on patterns from prior data or predefined dictionaries. This predictive mechanism operates dynamically with each keystroke, offering options that users can select to avoid typing the full term.[8] At its core, autocomplete relies on prefix matching, where suggestions are derived from terms in a database that begin with the exact sequence of characters entered by the user.[11] For instance, typing "aut" might suggest "autocomplete," "automatic," or "author" if those align with the input prefix. This approach ensures relevance by focusing on initial character sequences, facilitating quick recognition and selection without requiring full spelling.[12] Unlike auto-correction, which automatically replaces or flags misspelled words to fix errors during typing, autocomplete emphasizes prediction and suggestion without altering the original input unless explicitly chosen by the user.[13] Auto-correction targets inaccuracies like typos, whereas autocomplete aids in proactive completion for accurate, intended entries.[14] Simple implementations often appear as dropdown lists beneath input fields in web forms, allowing users to hover or click on highlighted suggestions for instant insertion.[15] These lists typically limit options to a few top matches to maintain usability, appearing only after a minimum number of characters to balance responsiveness and precision.[16]Original Purpose

Autocomplete was originally developed to minimize the number of keystrokes required for input and to alleviate cognitive load by anticipating user intent through recognition of common patterns in text or commands. This primary goal addressed the inefficiencies of manual data entry in early computing environments, where repetitive tasks demanded significant user effort. By suggesting completions based on partial inputs, the technology enabled faster interactions, particularly for users engaging in frequent typing or command execution.[17] The origins of autocomplete lie in the need for efficiency during repetitive tasks, such as command entry in command-line interfaces and form filling in early software systems. In these contexts, partial matches to predefined commands or fields allowed users to complete inputs rapidly without typing full sequences, reducing errors from manual repetition. An important application of word prediction techniques has been to assist individuals with disabilities by reducing the physical demands of typing and improving accessibility.[17] Autocomplete shares conceptual similarities with analog practices like shorthand notations in telegraphy and typing, where abbreviations and symbolic systems were used to accelerate communication and minimize transmission or writing costs. For example, telegraph operators employed shortened forms to convey messages more swiftly, drawing on common patterns to save time and reduce errors. These techniques inspired the principle of pattern-based efficiency in digital tools for faster data entry.[18]History

Early Developments

The concept of autocomplete has roots in 19th-century communication technologies, where efficiency in transmission and recording anticipated modern predictive mechanisms. In telegraphy, operators developed extensive shorthand systems of abbreviations to accelerate message sending over limited bandwidth. By the late 1800s, the Western Union 92 Code, a standard list of 92 abbreviations, was widely adopted for common words and phrases, such as "30" for "go ahead" or "RU" for "are you," allowing operators to anticipate and shorten frequent terms without losing meaning.[19][18] This practice effectively prefigured autocomplete by relying on patterned completions to reduce manual input. Similarly, stenography systems in the same era provided foundational ideas for rapid text entry through symbolic anticipation. Gregg shorthand, devised by John Robert Gregg and first published in 1888, employed a phonemic approach with curvilinear strokes that represented sounds and word endings, enabling writers to predict and abbreviate based on phonetic patterns rather than full orthography.[20] This method, which prioritized brevity and speed for professional transcription, influenced later input efficiency tools by demonstrating how structured prediction could streamline human writing processes. In the 1960s, these analog precursors transitioned to digital environments within early timesharing operating systems. One of the earliest implementations of digital autocomplete appeared in the Berkeley Timesharing System, developed at the University of California, Berkeley, for the SDS 940 computer between 1964 and 1967. This system featured command completion in its editor and interface, where partial inputs triggered automatic filling of filenames or commands, enhancing user efficiency in multi-user environments.[21] The origins of autocomplete trace back further to 1959, when MIT researcher Samuel Hawks Caldwell developed the Sinotype machine for inputting Chinese characters on a QWERTY keyboard, incorporating "minimum spelling" to suggest completions based on partial stroke inputs stored in electronic memory.[3] By the late 1960s and into the 1970s, similar features emerged in other systems like Multics (initiated in 1964 and operational by 1969), where file path completion in command-line interfaces allowed users to expand abbreviated directory paths interactively. In the 1970s, systems like Tenex introduced file name and command completion features to streamline terminal interactions.[22] These developments laid the groundwork for autocomplete as an efficiency tool in computing, focusing on reducing keystrokes in resource-constrained hardware.Key Milestones

In the 1980s, autocomplete features began to appear in productivity software, particularly word processors. WordPerfect, first released for DOS in 1982, integrated glossary capabilities that allowed users to create abbreviations expanding automatically into predefined text blocks, enhancing typing efficiency in professional writing tasks. The 1990s marked the transition of autocomplete to web-based applications. Netscape Navigator, launched in December 1994, introduced address bar completion, drawing from browsing history to suggest and auto-fill URLs as users typed, streamlining navigation in the emerging graphical web.[23] AltaVista's search engine, publicly launched in late 1995 and refined in 1996, offered advanced search operators to improve result relevance amid growing web content.[24] During the 2000s, autocomplete expanded to mobile devices and advanced search interfaces. The T9 predictive text system, invented in 1997 by Cliff Kushler at Tegic Communications, enabled efficient word prediction on numeric keypads and achieved widespread adoption by the early 2000s in feature phones, reducing keystrokes for SMS composition.[25] By the 1980s, the tcsh shell extended these capabilities, using the Escape key for completions in Unix environments.[5] In the 1990s, autocomplete advanced in programming tools, with Microsoft launching IntelliSense in Visual C++ 6.0 in 1998, providing code suggestions, parameter information, and browsing features to boost developer productivity.[6] The feature's popularity surged in web search with Google's 2004 release of Google Suggest, which used big data and JavaScript to predict queries in real-time.[7] Google's Instant Search, unveiled on September 8, 2010, revolutionized web querying by dynamically updating results in real time as users typed, reportedly saving 2 to 5 seconds per search on average.[26] The 2010s and 2020s brought AI-driven evolutions to autocomplete, shifting from rule-based to machine learning paradigms. Apple debuted QuickType in June 2014 with iOS 8, a predictive keyboard that analyzed context, recipient, and usage patterns to suggest personalized word completions, marking a leap in mobile input intelligence. In May 2018, Gmail rolled out Smart Compose, leveraging recurrent neural networks and language models to generate inline phrase and sentence suggestions during email drafting, boosting productivity for over a billion users.[27] More recently, GitHub Copilot, launched in technical preview on June 29, 2021, in partnership with OpenAI, extended AI autocomplete to code generation, suggesting entire functions and lines based on natural language prompts and context within integrated development environments.[28] As of 2025, further advancements include agentic AI tools like Devin, enabling multi-step code generation and autonomous development assistance beyond traditional line-level suggestions.[29]Types

Rule-Based Systems

Rule-based autocomplete systems employ fixed vocabularies, such as static dictionaries, combined with deterministic matching rules to generate suggestions. These rules typically involve exact prefix matching, where suggestions begin with the characters entered by the user, or fuzzy logic techniques that tolerate minor variations like misspellings through predefined similarity thresholds, such as edit distance calculations.[30][31] A prominent example is T9 predictive text, developed by Tegic Communications in 1995, which maps letters to the numeric keys 2 through 9 on mobile phone keypads and uses dictionary-based disambiguation to predict intended words from ambiguous key sequences.[25] Another instance is abbreviation expanders in text editors, where users define shortcuts that automatically replace short forms with predefined full phrases or sentences upon completion of the abbreviation, as implemented in tools like GNU Emacs' abbrev-mode. These systems offer predictability in behavior, as outcomes depend solely on explicit rules without variability from training data, and they incur low computational overhead, making them suitable for resource-constrained environments.[30] However, they are constrained to predefined phrases in the dictionary, struggling with novel or context-specific inputs that fall outside the fixed ruleset.[30] Rule-based approaches dominated autocomplete implementations from the 1990s through the 2000s, particularly in mobile phones where T9 became standard for SMS input on devices like Nokia handsets, and in early search engines employing simple dictionary lookups for query suggestions.[32][33]AI-Driven Systems

AI-driven autocomplete systems leverage machine learning algorithms to produce dynamic, context-sensitive suggestions that adapt to user input patterns, surpassing the limitations of predefined rules by learning from vast datasets of text sequences.[34] These systems employ probabilistic modeling to anticipate completions, enabling real-time personalization and improved accuracy in diverse scenarios such as query formulation or text entry.[35] Key techniques in AI-driven autocomplete include n-gram models, which estimate the probability of subsequent words based on sequences of preceding tokens observed in training corpora, providing a foundational statistical approach for prediction.[36] More advanced methods utilize recurrent neural networks (RNNs), particularly long short-term memory (LSTM) variants, to capture long-range dependencies in sequential data, allowing the model to maintain contextual memory across extended inputs.[37] Transformers further enhance this capability through self-attention mechanisms, enabling parallel processing of entire sequences to generate highly coherent suggestions without sequential bottlenecks. Notable examples include Google's Gboard, introduced in 2016, which integrates deep learning models for next-word prediction on mobile keyboards, processing touch inputs to suggest completions that account for typing errors and user habits.[37] In conversational interfaces, large language models (LLMs) power autocomplete features, as seen in platforms like ChatGPT since its 2022 launch, where they generate prompt continuations to streamline user interactions.[38] Recent advancements emphasize personalization by incorporating user history into model training, such as through federated learning techniques that update predictions based on aggregated, privacy-preserving data from individual devices. Multilingual support has also advanced via LLMs trained on diverse language corpora, facilitating seamless autocomplete across languages without language-specific rule sets, with notable improvements in models from 2023 onward.[39]Technologies

Algorithms and Data Structures

Autocomplete systems rely on specialized data structures to store and retrieve strings efficiently based on user prefixes. The trie, also known as a prefix tree, is a foundational structure for this purpose, organizing a collection of strings in a tree where each node represents a single character, and edges denote transitions between characters. This allows for rapid prefix matching, as searching for a prefix of length requires traversing nodes, independent of the total number of strings in the dataset. The trie was first proposed by René de la Briandais in 1959 for efficient file searching with variable-length keys, enabling storage and lookup in a way that minimizes comparisons for common prefixes.[40] To address space inefficiencies in standard tries, where long chains of single-child nodes can consume excessive memory, radix trees (also called compressed or Patricia tries) apply path compression by merging such chains into single edges labeled with substrings. This reduces the number of nodes while preserving lookup time for exact prefixes, making radix trees particularly suitable for large vocabularies in autocomplete applications. The radix tree concept was introduced by Donald R. Morrison in 1968 as PATRICIA, a practical algorithm for retrieving alphanumeric information with economical index space.[41] For search engine autocomplete, inverted indexes extend traditional full-text search structures to support prefix queries over query logs or document titles. An inverted index maps terms to postings lists of documents or queries containing them, but for autocomplete, it is adapted to index prefixes or n-grams, allowing quick retrieval of candidate completions from massive datasets. This approach combines inverted indexes with succinct data structures to achieve low-latency suggestions even for billions of historical queries. Hash tables provide an alternative for quick dictionary access in simpler autocomplete scenarios, such as local spell-checkers, where exact string lookups are hashed for average-case retrieval, though they lack inherent support for prefix operations without additional modifications.[42] Basic algorithms for generating suggestions often involve traversing the trie structure after reaching the prefix node. Depth-first search (DFS) can enumerate and rank completions by recursively visiting child nodes, prioritizing based on frequency or other metrics stored at leaf nodes. For handling user typos, approximate matching using Levenshtein distance (edit distance) computes the minimum operations (insertions, deletions, substitutions) needed to transform the input prefix into a valid string, enabling error-tolerant suggestions within a bounded distance threshold. This is integrated into trie-based systems by searching nearby nodes or using dynamic programming on the tree paths.[43] Scalability in autocomplete requires handling real-time queries on vast datasets, such as the billions processed daily by major search engines. Techniques like distributed indexing across clusters, caching frequent prefixes, and using compressed tries ensure sub-millisecond response times, with systems partitioning data by prefix to parallelize lookups.[42]Prediction Mechanisms

Autocomplete prediction mechanisms begin with the tokenization of the user's input prefix into discrete units, typically at the word level, to enable efficient matching and scoring against stored data structures. Once tokenized, the core process involves computing conditional probabilities for potential completions, estimating the likelihood P(completion|prefix) to generate candidate suggestions. This probabilistic scoring often relies on Bayes' theorem to invert dependencies, formulated as P(completion|prefix) = P(prefix|completion) * P(completion) / P(prefix), where P(completion) reflects prior frequencies from query logs, and the likelihood terms capture how well the prefix aligns with historical completions. Such approaches ensure that suggestions are generated dynamically post-retrieval, prioritizing completions that maximize the posterior probability based on observed data. A foundational method for probability estimation in these systems is the n-gram model, which approximates the conditional probability of the next word given the preceding n-1 words: P(w_i | w_{i-n+1} ... w_{i-1}). This is typically computed via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) from a training corpus, where the probability is the normalized count of the n-gram divided by the count of its prefix: P(w_i | w_{i-n+1} ... w_{i-1}) = C(w_{i-n+1} ... w_i) / C(w_{i-n+1} ... w_{i-1}), with C denoting empirical counts.[44] For instance, in query auto-completion, trigram models derived from search logs have been used to predict subsequent terms, enhancing relevance for short prefixes by leveraging sequential patterns.[42] Ranking of generated candidates commonly employs frequency-based methods, such as the Most Popular Completion (MPC) approach, which scores suggestions by their historical query frequency and ranks the most common first to reflect user intent patterns.[42] Context-aware ranking extends this by incorporating semantic similarity through embeddings in vector spaces; for example, whole-query embeddings generated via models like fastText compute cosine distances between the prefix and candidate completions, adjusting scores to favor semantically related suggestions within user sessions.[45] In advanced neural models, prediction often integrates beam search to explore the top-k probable paths during generation, balancing completeness and efficiency by maintaining a fixed-width beam of hypotheses and selecting the highest-scoring sequence at each step.[46] As of 2025, transformer-based large language models (LLMs) have further advanced these mechanisms, providing generative and highly contextual predictions for autocomplete in search engines and applications. For example, integrations like Google's AI Mode in autocomplete suggestions leverage LLMs to offer more intuitive, multi-turn query completions.[47] Personalization further refines these mechanisms by adjusting probability scores with user-specific data, such as boosting rankings for queries matching n-gram similarities in short-term session history or long-term profiles, yielding improvements like up to 9.42% in mean reciprocal rank (MRR) on large-scale search engines.[48]Applications

Web and Search Interfaces

Autocomplete plays a central role in web browsers' address bars, where it provides URL and history-based suggestions to streamline navigation. In Google Chrome, the Omnibox—introduced with the browser's launch in 2008—integrates the address and search fields into a single interface that offers autocomplete suggestions drawn from local browsing history and bookmarks as well as remote data from search providers.[49] This hybrid approach allows users to receive instant predictions for frequently visited sites or search queries, reducing typing effort and enhancing efficiency.[49] In web forms, autocomplete enhances user input for fields such as emails, addresses, or phone numbers by suggesting predefined or contextual options. The HTML5<datalist> element enables this functionality by associating a list of <option> elements with an <input> field via the list attribute, allowing browsers to display a dropdown of suggestions as the user types.[50] This standard-compliant feature, part of the HTML specification, supports various input types including email and URL, promoting faster form completion while maintaining accessibility.[51]

Search engines leverage autocomplete to predict and suggest queries based on aggregated user data, significantly improving search discovery. Google's Suggest feature, launched in December 2004 as a Labs project, draws from global query logs to provide real-time suggestions that reflect popular or trending terms, helping users refine their searches efficiently.[52] This API-driven system has since become integral to search interfaces, influencing how billions of daily queries are initiated.[52]

On mobile web platforms, autocomplete adapts to touch-based interactions, with browsers optimizing for smaller screens and gesture inputs. Apple's Safari on iOS, for instance, incorporates AutoFill for address bar suggestions and form fields, using contact information and history to offer predictions that users can select via taps or swipes, a capability refined throughout the 2010s to support seamless mobile browsing.[53] These adaptations ensure that autocomplete remains intuitive on touch devices, integrating with iOS features like iCloud Keychain for secure, cross-device consistency.[53]