Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electronic mail (usually shortened to email; alternatively hyphenated e-mail) is a method of transmitting and receiving digital messages using electronic devices over a computer network. It was conceived in the late–20th century as the digital version of, or counterpart to, mail (hence e- + mail). Email is a ubiquitous and very widely used communication medium; in current use, an email address is often treated as a basic and necessary part of many processes in business, commerce, government, education, entertainment, and other spheres of daily life in most countries.

Email operates across computer networks, primarily the Internet, and also local area networks. Today's email systems are based on a store-and-forward model. Email servers accept, forward, deliver, and store messages. Neither the users nor their computers are required to be online simultaneously; they need to connect, typically to a mail server or a webmail interface to send or receive messages or download it.

Originally a text-only ASCII communications medium, Internet email was extended by MIME to carry text in expanded character sets and multimedia content such as images. International email, with internationalized email addresses using UTF-8, is standardized but not widely adopted.[1]

Terminology

[edit]The term electronic mail has been in use with its modern meaning since 1975, and variations of the shorter E-mail have been in use since 1979:[2][3]

- email is now the common form, and recommended by style guides.[4][5][6] It is the form required by IETF Requests for Comments (RFC) and working groups.[7] This spelling also appears in most dictionaries.[8][9][4][10]

- e-mail was originally the form favored in edited published American English and British English writing, and was formerly preferred by some style guides.[4]

- E-mail is sometimes used.[11] The original usage in June 1979 occurred in the journal Electronics in reference to the United States Postal Service initiative called E-COM, which was developed in the late 1970s and operated in the early 1980s.[2][3]

- EMAIL was used by CompuServe starting in April 1981, which popularized the term.[12][13]

- EMail is a traditional form used in RFCs for the "Author's Address".

The service is often simply referred to as mail, and a single piece of electronic mail is called a message. The conventions for fields within emails—the "To", "From", "CC", "BCC" etc.—began with RFC-680 in 1975.[14]

An Internet email consists of an envelope and content;[15] the content consists of a header and a body.[16]

History

[edit]

Computer-based messaging between users of the same system became possible after the advent of time-sharing in the early 1960s, with a notable implementation by MIT's CTSS project in 1965.[17] Most developers of early mainframes and minicomputers developed similar, but generally incompatible, mail applications. In 1971 the first ARPANET network mail was sent, introducing the now-familiar address syntax with the '@' symbol designating the user's system address.[18] Over a series of RFCs, conventions were refined for sending mail messages over the File Transfer Protocol.

Proprietary electronic mail systems soon began to emerge. IBM, CompuServe and Xerox used in-house mail systems in the 1970s; CompuServe sold a commercial intraoffice mail product in 1978 to IBM and to Xerox from 1981.[nb 1][19][20][21] DEC's ALL-IN-1 and Hewlett-Packard's HPMAIL (later HP DeskManager) were released in 1982; development work on the former began in the late 1970s and the latter became the world's largest selling email system.[22][23]

The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) was implemented on the ARPANET in 1983. LAN email systems emerged in the mid-1980s. For a time in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it seemed likely that either a proprietary commercial system or the X.400 email system, part of the Government Open Systems Interconnection Profile (GOSIP), would predominate. However, once the final restrictions on carrying commercial traffic over the Internet ended in 1995,[24][25] a combination of factors made the current Internet suite of SMTP, POP3 and IMAP email protocols the standard (see Protocol Wars).[26][27]

Operation

[edit]The following is a typical sequence of events that takes place when sender Alice transmits a message using a mail user agent (MUA) addressed to the email address of the recipient.[28]

- The MUA formats the message in email format and uses the submission protocol, a profile of the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), to send the message content to the local mail submission agent (MSA), in this case smtp.a.org.

- The MSA determines the destination address provided in the SMTP protocol (not from the message header)—in this case, bob@b.org—which is a fully qualified domain address (FQDA). The part before the @ sign is the local part of the address, often the username of the recipient, and the part after the @ sign is a domain name. The MSA resolves a domain name to determine the fully qualified domain name of the mail server in the Domain Name System (DNS).

- The DNS server for the domain b.org (ns.b.org) responds with any MX records listing the mail exchange servers for that domain, in this case mx.b.org, a message transfer agent (MTA) server run by the recipient's ISP.[29]

- smtp.a.org sends the message to mx.b.org using SMTP. This server may need to forward the message to other MTAs before the message reaches the final message delivery agent (MDA).

- The MDA delivers it to the mailbox of user bob.

- Bob's MUA picks up the message using either the Post Office Protocol (POP3) or the Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP).

In addition to this example, alternatives and complications exist in the email system:

- Alice or Bob may use a client connected to a corporate email system, such as IBM Lotus Notes or Microsoft Exchange. These systems often have their own internal email format and their clients typically communicate with the email server using a vendor-specific, proprietary protocol. The server sends or receives email via the Internet through the product's Internet mail gateway which also does any necessary reformatting. If Alice and Bob work for the same company, the entire transaction may happen completely within a single corporate email system.

- Alice may not have an MUA on her computer but instead may connect to a webmail service.

- Alice's computer may run its own MTA, so avoiding the transfer at step 1.

- Bob may pick up his email in many ways, for example logging into mx.b.org and reading it directly, or by using a webmail service.

- Domains usually have several mail exchange servers so that they can continue to accept mail even if the primary is not available.

Many MTAs used to accept messages for any recipient on the Internet and do their best to deliver them. Such MTAs are called open mail relays. This was very important in the early days of the Internet when network connections were unreliable.[30][31] However, this mechanism proved to be exploitable by originators of unsolicited bulk email and as a consequence open mail relays have become rare,[32] and many MTAs do not accept messages from open mail relays.

Email pre-dates instant messaging, and transmission favors reliability over speed, in order to be able to cope with unreliable network links and busy servers (more common in the early days of the Internet). Reasons for slower delivery include:[33]

- Messages going to a large number of recipients require more processing

- Large messages (e.g. with large attachments) require more time to transmit over the network

- Messages need to pass through multiple servers (sometimes multiple servers inside the same organization)

- One or more mail servers are overloaded (possibly due to spam or denial-of-service attack) and queuing incoming mail or temporarily refusing incoming connections

- SMTP requires multiple back-and-forths, which can amplify the impact of a slow network or dropped packets

- Sender or recipient temporarily disconnected from the network (e.g. a laptop out of wifi range)

- Slow DNS response

- Server down for maintenance or malfunction

Mail can be queued and retried for up to five days before senders are notified of a permanent delivery failure.[33] Messages are timestamped as they pass through each server, allowing for diagnosis of slow delivery, though analysis is complicated by time zones and computer clocks that are inaccurately set.[33]

Email messages classified as spam by a spam filter may be sorted into a separate folder which the recipient must check manually, or may be dropped entirely.

Message format

[edit]The basic Internet message format used for email[34] is defined by RFC 5322, with encoding of non-ASCII data and multimedia content attachments defined in RFC 2045 through RFC 2049, collectively called Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions or MIME. The extensions in International email apply only to email. RFC 5322 replaced RFC 2822 in 2008. Earlier, in 2001, RFC 2822 had in turn replaced RFC 822, which had been the standard for Internet email for decades. Published in 1982, RFC 822 was based on the earlier RFC 733 for the ARPANET.[35]

Internet email messages consist of two sections, "header" and "body". These are known as "content".[36][37] The header is structured into fields such as From, To, CC, Subject, Date, and other information about the email. In the process of transporting email messages between systems, SMTP communicates delivery parameters and information using message header fields. The body contains the message, as unstructured text, sometimes containing a signature block at the end. The header is separated from the body by a blank line.

Message header

[edit]RFC 5322 specifies the syntax of the email header. Each email message has a header (the "header section" of the message, according to the specification), comprising a number of fields ("header fields"). Each field has a name ("field name" or "header field name"), followed by the separator character ":", and a value ("field body" or "header field body").

Each field name begins in the first character of a new line in the header section, and begins with a non-whitespace printable character. It ends with the separator character ":". The separator is followed by the field value (the "field body"). The value can continue onto subsequent lines if those lines have space or tab as their first character. Field names and, without SMTPUTF8, field bodies are restricted to 7-bit ASCII characters. Some non-ASCII values may be represented using MIME encoded words.

Header fields

[edit]Email header fields can be multi-line, with each line recommended to be no more than 78 characters, although the limit is 998 characters.[38] Header fields defined by RFC 5322 contain only US-ASCII characters; for encoding characters in other sets, a syntax specified in RFC 2047 may be used.[39] In some examples, the IETF EAI working group defines some standards track extensions,[40][41] replacing previous experimental extensions so UTF-8 encoded Unicode characters may be used within the header. In particular, this allows email addresses to use non-ASCII characters. Such addresses are supported by Google and Microsoft products, and promoted by some government agents.[42]

The message header must include at least the following fields:[43][44]

- From: The email address, and, optionally, the name of the author(s). Some email clients are changeable through account settings.

- Date: The local time and date the message was written. Like the From: field, many email clients fill this in automatically before sending. The recipient's client may display the time in the format and time zone local to them.

RFC 3864 describes registration procedures for message header fields at the IANA; it provides for permanent and provisional field names, including also fields defined for MIME, netnews, and HTTP, and referencing relevant RFCs. Common header fields for email include:[45]

- To: The email address(es), and optionally name(s) of the message's recipient(s). Indicates primary recipients (multiple allowed), for secondary recipients see Cc: and Bcc: below.

- Subject: A brief summary of the topic of the message. Certain abbreviations are commonly used in the subject, including "RE:" and "FW:".

- Cc: Carbon copy; Many email clients mark email in one's inbox differently depending on whether they are in the To: or Cc: list.

- Bcc: Blind carbon copy; addresses are usually only specified during SMTP delivery, and not usually listed in the message header.

- Content-Type: Information about how the message is to be displayed, usually a MIME type.

- Precedence: commonly with values "bulk", "junk", or "list"; used to indicate automated "vacation" or "out of office" responses should not be returned for this mail, e.g. to prevent vacation notices from sent to all other subscribers of a mailing list. Sendmail uses this field to affect prioritization of queued email, with "Precedence: special-delivery" messages delivered sooner. With modern high-bandwidth networks, delivery priority is less of an issue than it was. Microsoft Exchange respects a fine-grained automatic response suppression mechanism, the X-Auto-Response-Suppress field.[46]

- Message-ID: Also an automatic-generated field to prevent multiple deliveries and for reference in In-Reply-To: (see below).

- In-Reply-To: Message-ID of the message this is a reply to. Used to link related messages together. This field only applies to reply messages.

- List-Unsubscribe: HTTP link to unsubscribe from a mailing list.

- References: Message-ID of the message this is a reply to, and the message-id of the message the previous reply was a reply to, etc.

- Reply-To: Address should be used to reply to the message.

- Sender: Address of the sender acting on behalf of the author listed in the From: field (secretary, list manager, etc.).

- Archived-At: A direct link to the archived form of an individual email message.

The To: field may be unrelated to the addresses to which the message is delivered. The delivery list is supplied separately to the transport protocol, SMTP, which may be extracted from the header content. The "To:" field is similar to the addressing at the top of a conventional letter delivered according to the address on the outer envelope. In the same way, the "From:" field may not be the sender. Some mail servers apply email authentication systems to messages relayed. Data pertaining to the server's activity is also part of the header, as defined below.

SMTP defines the trace information of a message saved in the header using the following two fields:[47]

- Received: after an SMTP server accepts a message, it inserts this trace record at the top of the header (last to first).

- Return-Path: after the delivery SMTP server makes the final delivery of a message, it inserts this field at the top of the header.

Other fields added on top of the header by the receiving server may be called trace fields.[48]

- Authentication-Results: after a server verifies authentication, it can save the results in this field for consumption by downstream agents.[49]

- Received-SPF: stores results of SPF checks in more detail than Authentication-Results.[50]

- DKIM-Signature: stores results of DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) decryption to verify the message was not changed after it was sent.[51]

- Auto-Submitted: is used to mark automatic-generated messages.[52]

- VBR-Info: claims VBR whitelisting[53]

Message body

[edit]Content encoding

[edit]Internet email was designed for 7-bit ASCII.[54] Most email software is 8-bit clean, but must assume it will communicate with 7-bit servers and mail readers. The MIME standard introduced character set specifiers and two content transfer encodings to enable transmission of non-ASCII data: quoted printable for mostly 7-bit content with a few characters outside that range and base64 for arbitrary binary data. The 8BITMIME and BINARY extensions were introduced to allow transmission of mail without the need for these encodings, but many mail transport agents may not support them. In some countries, e-mail software violates RFC 5322 by sending raw[nb 2] non-ASCII text and several encoding schemes co-exist; as a result, by default, the message in a non-Latin alphabet language appears in non-readable form (the only exception is a coincidence if the sender and receiver use the same encoding scheme). Therefore, for international character sets, Unicode is growing in popularity.[55]

Plain text and HTML

[edit]Most modern graphic email clients allow the use of either plain text or HTML for the message body at the option of the user. HTML email messages often include an automatic-generated plain text copy for compatibility.

Advantages of HTML include the ability to include in-line links and images, set apart previous messages in block quotes, wrap naturally on any display, use emphasis such as underlines and italics, and change font styles. Disadvantages include the increased size of the email, privacy concerns about web bugs, abuse of HTML email as a vector for phishing attacks and the spread of malicious software.[56]

Some e-mail clients interpret the body as HTML even in the absence of a Content-Type: html header field; this may cause various problems.

Some web-based mailing lists recommend all posts be made in plain text, with 72 or 80 characters per line for all the above reasons,[57][58] and because they have a significant number of readers using text-based email clients such as Mutt. Various informal conventions evolved for marking up plain text in email and usenet posts, which later led to the development of formal languages like setext (c. 1992) and many others, the most popular of them being markdown.

Some Microsoft email clients may allow rich formatting using their proprietary Rich Text Format (RTF), but this should be avoided unless the recipient is guaranteed to have a compatible email client.[59]

Servers and client applications

[edit]

Messages are exchanged between hosts using the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol with software programs called mail transfer agents (MTAs); and delivered to a mail store by programs called mail delivery agents (MDAs, also sometimes called local delivery agents, LDAs). Accepting a message obliges an MTA to deliver it,[60] and when a message cannot be delivered, that MTA must send a bounce message back to the sender, indicating the problem.

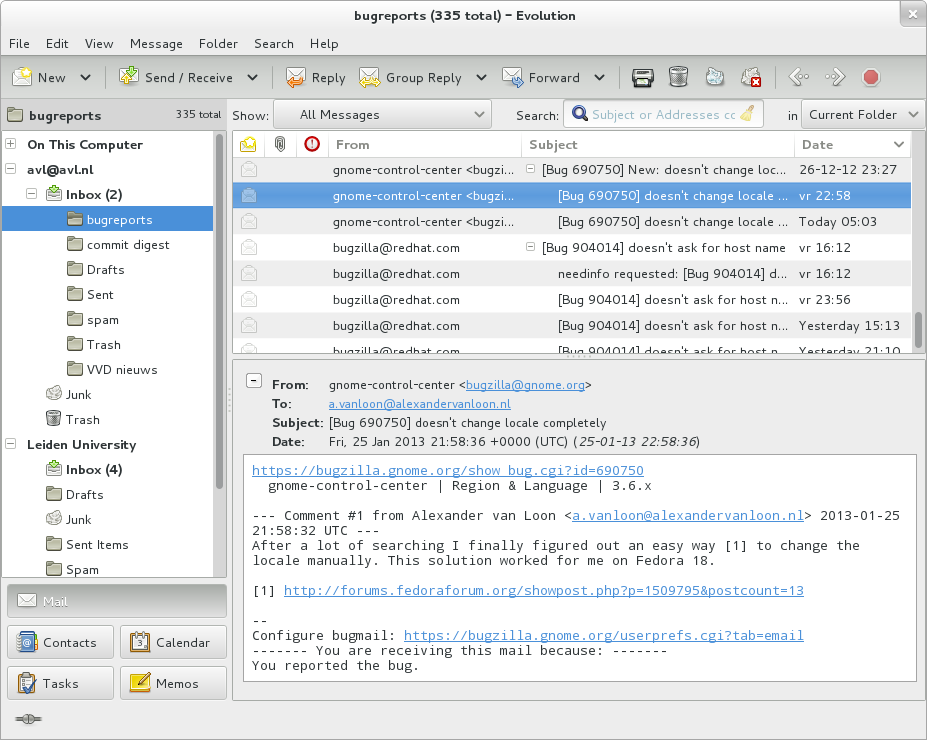

Users can retrieve their messages from servers using standard protocols such as POP or IMAP, or, as is more likely in a large corporate environment, with a proprietary protocol specific to Novell Groupwise, Lotus Notes or Microsoft Exchange Servers. Programs used by users for retrieving, reading, and managing email are called mail user agents (MUAs).

When opening an email, it is marked as "read", which typically visibly distinguishes it from "unread" messages on clients' user interfaces. Email clients may allow hiding read emails from the inbox so the user can focus on the unread.[61]

Mail can be stored on the client, on the server side, or in both places. Standard formats for mailboxes include Maildir and mbox. Several prominent email clients use their own proprietary format and require conversion software to transfer email between them. Server-side storage is often in a proprietary format but since access is through a standard protocol such as IMAP, moving email from one server to another can be done with any MUA supporting the protocol.

Many current email users do not run MTA, MDA or MUA programs themselves, but use a web-based email platform, such as Gmail or Yahoo! Mail, that performs the same tasks.[62] Such webmail interfaces allow users to access their mail with any standard web browser, from any computer, rather than relying on a local email client.

Filename extensions

[edit]Upon reception of email messages, email client applications save messages in operating system files in the file system. Some clients save individual messages as separate files, while others use various database formats, often proprietary, for collective storage. A historical standard of storage is the mbox format. The specific format used is often indicated by special filename extensions:

eml- Used by many email clients including Novell GroupWise, Microsoft Outlook Express, Lotus notes, Windows Mail, Mozilla Thunderbird, and Postbox. The files contain the email contents as plain text in MIME format, containing the email header and body, including attachments in one or more of several formats.

emlx- Used by Apple Mail.

msg- Used by Microsoft Office Outlook and OfficeLogic Groupware.

mbx- Used by Opera Mail, KMail, and Apple Mail based on the mbox format.

Some applications (like Apple Mail) leave attachments encoded in messages for searching while also saving separate copies of the attachments. Others separate attachments from messages and save them in a specific directory.

URI scheme mailto

[edit]The URI scheme, as registered with the IANA, defines the mailto: scheme for SMTP email addresses. Though its use is not strictly defined, URLs of this form are intended to be used to open the new message window of the user's mail client when the URL is activated, with the address as defined by the URL in the To: field.[63][64] Many clients also support query string parameters for the other email fields, such as its subject line or carbon copy recipients.[65]

Types

[edit]Web-based email

[edit]Many email providers have a web-based email client. This allows users to log into the email account by using any compatible web browser to send and receive their email. Mail is typically not downloaded to the web client, so it cannot be read without a current Internet connection.

POP3 email servers

[edit]The Post Office Protocol 3 (POP3) is a mail access protocol used by a client application to read messages from the mail server. Received messages are often deleted from the server. POP supports simple download-and-delete requirements for access to remote mailboxes (termed maildrop in the POP RFC's).[66] POP3 allows downloading messages on a local computer and reading them even when offline.[67][68]

IMAP email servers

[edit]The Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) provides features to manage a mailbox from multiple devices. Small portable devices like smartphones are increasingly used to check email while traveling and to make brief replies, larger devices with better keyboard access being used to reply at greater length. IMAP shows the headers of messages, the sender and the subject and the device needs to request to download specific messages. Usually, the mail is left in folders in the mail server.

MAPI email servers

[edit]Messaging Application Programming Interface (MAPI) is used by Microsoft Outlook to communicate to Microsoft Exchange Server—and to a range of other email server products such as Axigen Mail Server, Kerio Connect, Scalix, Zimbra, HP OpenMail, IBM Lotus Notes, Zarafa, and Bynari where vendors have added MAPI support to allow their products to be accessed directly via Outlook.

Uses

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

Business and organizational use

[edit]Email has been widely accepted by businesses, governments and non-governmental organizations in the developed world, and it is one of the key parts of an 'e-revolution' in workplace communication (with the other key plank being widespread adoption of highspeed Internet). A sponsored 2010 study on workplace communication found 83% of U.S. knowledge workers felt email was critical to their success and productivity at work.[69]

It has some key benefits to business and other organizations, including:

- Facilitating logistics

- Much of the business world relies on communications between people who are not physically in the same building, area, or even country; setting up and attending an in-person meeting, telephone call, or conference call can be inconvenient, time-consuming, and costly. Email provides a method of exchanging information between two or more people with no set-up costs and that is generally far less expensive than a physical meeting or phone call.

- Helping with synchronization

- With real time communication by meetings or phone calls, participants must work on the same schedule, and each participant must spend the same amount of time in the meeting or call. Email allows asynchrony: each participant may control their schedule independently. Batch processing of incoming emails can improve workflow compared to interrupting calls.

- Reducing cost

- Sending an email is much less expensive than sending postal mail, or long distance telephone calls, telex or telegrams.

- Increasing speed

- Much faster than most of the alternatives.

- Creating a "written" record

- Unlike a telephone or in-person conversation, email by its nature creates a detailed written record of the communication, the identity of the sender(s) and recipient(s) and the date and time the message was sent. In the event of a contract or legal dispute, saved emails can be used to prove that an individual was advised of certain issues, as each email has the date and time recorded on it.

- Possibility of auto-processing and improved distribution

- As well pre-processing of customer's orders or addressing the person in charge can be realized by automated procedures.

Email marketing

[edit]Email marketing via "opt-in" is often successfully used to send special sales offerings and new product information.[70] Depending on the recipient's culture,[71] email sent without permission—such as an "opt-in"—is likely to be viewed as unwelcome "email spam".

Personal use

[edit]Personal computer

[edit]Many users access their personal emails from friends and family members using a personal computer in their house or apartment.

Mobile

[edit]Email has become used on smartphones and on all types of computers. Mobile "apps" for email increase accessibility to the medium for users who are out of their homes. While in the earliest years of email, users could only access email on desktop computers, in the 2010s, it is possible for users to check their email when they are away from home, whether they are across town or across the world. Alerts can also be sent to the smartphone or other devices to notify them immediately of new messages. This has given email the ability to be used for more frequent communication between users and allowed them to check their email and write messages throughout the day. As of 2011[update], there were approximately 1.4 billion email users worldwide and 50 billion non-spam emails that were sent daily.[64]

Individuals often check emails on smartphones for both personal and work-related messages. It was found that US adults check their email more than they browse the web or check their Facebook accounts, making email the most popular activity for users to do on their smartphones. 78% of the respondents in the study revealed that they check their email on their phone.[72] It was also found that 30% of consumers use only their smartphone to check their email, and 91% were likely to check their email at least once per day on their smartphone. However, the percentage of consumers using email on a smartphone ranges and differs dramatically across different countries. For example, in comparison to 75% of those consumers in the US who used it, only 17% in India did.[73]

Declining use among young people

[edit]As of 2010[update], the number of Americans visiting email web sites had fallen 6 percent after peaking in November 2009. For persons 12 to 17, the number was down 18 percent. Young people preferred instant messaging, texting and social media. Technology writer Matt Richtel said in The New York Times that email was like the VCR, vinyl records and film cameras—no longer cool and something older people do.[74][75]

A 2015 survey of Android users showed that persons 13 to 24 used messaging apps 3.5 times as much as those over 45, and were far less likely to use email.[76]

Issues

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2016) |

Attachment size limitation

[edit]Email messages may have one or more attachments, which are additional files that are appended to the email. Typical attachments include Microsoft Word documents, PDF documents, and scanned images of paper documents. In principle, there is no technical restriction on the size or number of attachments. However, in practice, email clients, servers, and Internet service providers implement various limitations on the size of files, or complete email – typically to 25MB or less.[77][78][79] Furthermore, due to technical reasons, attachment sizes as seen by these transport systems can differ from what the user sees,[80] which can be confusing to senders when trying to assess whether they can safely send a file by email. Where larger files need to be shared, various file hosting services are available and commonly used.[81][82]

Information overload

[edit]The ubiquity of email for knowledge workers and "white collar" employees has led to concerns that recipients face an "information overload" in dealing with increasing volumes of email.[83][84] With the growth in mobile devices, by default employees may also receive work-related emails outside of their working day. This can lead to increased stress and decreased satisfaction with work. Some observers even argue it could have a significant negative economic effect,[85] as efforts to read the many emails could reduce productivity.

Spam

[edit]Email "spam" is unsolicited bulk email. The low cost of sending such email meant that, by 2003, up to 30% of total email traffic was spam,[86][87][88] and was threatening the usefulness of email as a practical tool. The US CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 and similar laws elsewhere[89] had some impact, and a number of effective anti-spam techniques now largely mitigate the impact of spam by filtering or rejecting it for most users,[90] but the volume sent is still very high—and increasingly consists not of advertisements for products, but malicious content or links.[91] In September 2017, for example, the proportion of spam to legitimate email rose to 59.56%.[92] The percentage of spam email in 2021 is estimated to be 85%.[93][better source needed]

Malware

[edit]Emails are a major vector for the distribution of malware.[94] This is often achieved by attaching malicious programs to the message and persuading potential victims to open the file.[95] Types of malware distributed via email include computer worms[96] and ransomware.[97]

Email spoofing

[edit]Email spoofing occurs when the email message header is designed to make the message appear to come from a known or trusted source. Email spam and phishing methods typically use spoofing to mislead the recipient about the true message origin. Email spoofing may be done as a prank, or as part of a criminal effort to defraud an individual or organization. An example of a potentially fraudulent email spoofing is if an individual creates an email that appears to be an invoice from a major company, and then sends it to one or more recipients. In some cases, these fraudulent emails incorporate the logo of the purported organization and even the email address may appear legitimate.

Email bombing

[edit]Email bombing is the intentional sending of large volumes of messages to a target address. The overloading of the target email address can render it unusable and can even cause the mail server to crash.

Privacy concerns

[edit]Today it can be important to distinguish between the Internet and internal email systems. Internet email may travel and be stored on networks and computers without the sender's or the recipient's control. During the transit time it is possible that third parties read or even modify the content. Internal mail systems, in which the information never leaves the organizational network, may be more secure, although information technology personnel and others whose function may involve monitoring or managing may be accessing the email of other employees.

Email privacy, without some security precautions, can be compromised because:

- email messages are generally not encrypted.

- email messages have to go through intermediate computers before reaching their destination, meaning it is relatively easy for others to intercept and read messages.

- many Internet Service Providers (ISP) store copies of email messages on their mail servers before they are delivered. The backups of these can remain for up to several months on their server, despite deletion from the mailbox.

- the "Received:"-fields and other information in the email can often identify the sender, preventing anonymous communication.

- web bugs invisibly embedded in HTML content can alert the sender of any email whenever an email is rendered as HTML (some e-mail clients do this when the user reads, or re-reads the e-mail) and from which IP address. It can also reveal whether an email was read on a smartphone or a PC, or Apple Mac device via the user agent string.

There are cryptography applications that can serve as a remedy to one or more of the above. For example, Virtual Private Networks or the Tor network can be used to encrypt traffic from the user machine to a safer network while GPG, PGP, SMEmail,[98] or S/MIME can be used for end-to-end message encryption, and SMTP STARTTLS or SMTP over Transport Layer Security/Secure Sockets Layer can be used to encrypt communications for a single mail hop between the SMTP client and the SMTP server.

Additionally, many mail user agents do not protect logins and passwords, making them easy to intercept by an attacker. Encrypted authentication schemes such as SASL prevent this. Finally, the attached files share many of the same hazards as those found in peer-to-peer filesharing. Attached files may contain trojans or viruses.

Legal contracts

[edit]It is possible for an exchange of emails to form a binding contract, so users must be careful about what they send through email correspondence.[99][100] A signature block on an email may be interpreted as satisfying a signature requirement for a contract.[101]

Flaming

[edit]Flaming occurs when a person sends a message (or many messages) with angry or antagonistic content. The term is derived from the use of the word incendiary to describe particularly heated email discussions. The ease and impersonality of email communications mean that the social norms that encourage civility in person or via telephone do not exist and civility may be forgotten.[102]

Email bankruptcy

[edit]Also known as "email fatigue", email bankruptcy is when a user ignores a large number of email messages after falling behind in reading and answering them. The reason for falling behind is often due to information overload and a general sense there is so much information that it is not possible to read it all. As a solution, people occasionally send a "boilerplate" message explaining that their email inbox is full, and that they are in the process of clearing out all the messages. Harvard University law professor Lawrence Lessig is credited with coining this term, but he may only have popularized it.[103]

Internationalization

[edit]Originally Internet email was completely ASCII text-based. MIME now allows body content text and some header content text in international character sets, but other headers and email addresses using UTF-8, while standardized[104] have yet to be widely adopted.[1][105]

Tracking of sent mail

[edit]The original SMTP mail service provides limited mechanisms for tracking a transmitted message, and none for verifying that it has been delivered or read. It requires that each mail server must either deliver it onward or return a failure notice (bounce message), but both software bugs and system failures can cause messages to be lost. To remedy this, the IETF introduced Delivery Status Notifications (delivery receipts) and Message Disposition Notifications (return receipts); however, these are not universally deployed in production.[nb 3]

Many ISPs now deliberately disable non-delivery reports (NDRs) and delivery receipts due to the activities of spammers:

- Delivery Reports can be used to verify whether an address exists and if so, this indicates to a spammer that it is available to be spammed.

- If the spammer uses a forged sender email address (email spoofing), then the innocent email address that was used can be flooded with NDRs from the many invalid email addresses the spammer may have attempted to mail. These NDRs then constitute spam (backscatter) from the ISP to the innocent user.

In the absence of standard methods, a range of system based around the use of web bugs have been developed. However, these are often seen as underhand or raising privacy concerns,[108][109] and only work with email clients that support rendering of HTML. Many mail clients now default to not showing "web content".[110] Webmail providers can also disrupt web bugs by pre-caching images.[111]

See also

[edit]- Anonymous remailer

- Anti-spam techniques

- biff

- Bounce message

- Comparison of email clients

- Dark Mail Alliance

- Disposable email address

- E-card

- Electronic mailing list

- Email art

- Email authentication

- Email digest

- Email encryption

- Email hosting service

- Email hub

- Email storm

- Email tracking

- HTML email

- Information overload

- Internet fax

- List of email subject abbreviations

- MCI Mail

- Netiquette

- Posting style

- Privacy-enhanced Electronic Mail

- Push email

- RSS

- Telegraphy

- Unicode and email

- Usenet quoting

- Webmail, Comparison of webmail providers

- X-Originating-IP

- X.400

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "DataMail: World's first free linguistic email service supports eight India languages". Archived from the original on October 22, 2016.

- ^ a b "email noun earlier than 1979". Oxford English Dictionary. October 25, 2012. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Ohlheiser, Abby (July 28, 2015). "Why the first use of the word 'e-mail' may be lost forever". Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c "From E-mail to Email: Is the Sky Falling?". CMOS Shop Talk. Chicago Manual of Style. October 11, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2024.

- ^ "Yahoo style guide". Styleguide.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ "AP Removes Hyphen From 'Email' In Style Guide". Huffington Post. New York City. March 18, 2011. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015.

- ^ "RFC Editor Terms List". IETF. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. This is suggested by the RFC Document Style Guide Archived 2015-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ AskOxford Language Query team. "What is the correct way to spell 'e' words such as 'email', 'ecommerce', 'egovernment'?". FAQ. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on July 1, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

We recommend email, this is the common form

- ^ "Reference.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ ""RFC Style Guide", Table of decisions on consistent use in RFC". Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ Israel, Mark. "How do you spell "e-mail"?". Alt-usage-english.org. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ thaigh (2015). "Did V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai Invent Email?". SIGCIS. Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Masnick, Mike (May 22, 2019). "Laying Out All The Evidence: Shiva Ayyadurai Did Not Invent Email". Techdirt. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Pexton, Patrick B. (March 1, 2012). "Origins of e-mail: My mea culpa". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "Mail Objects". Simple Mail Transfer Protocol. IETF. sec. 2.3.1. doi:10.17487/RFC5321. RFC 5321.

SMTP transports a mail object. A mail object contains an envelope and content.

- ^ "Mail Objects". Simple Mail Transfer Protocol. IETF. sec. 2.3.1. doi:10.17487/RFC5321. RFC 5321.

The SMTP content is sent in the SMTP DATA protocol unit, and has two parts: the header section and the body. If the content conforms to other contemporary standards, the header section is a collection of header fields, each consisting of a header name, a colon, and data, structured as in the message format specification

- ^ Tom Van Vleck. "The History of Electronic Mail". Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2005.

- ^ Ray Tomlinson. "The First Network Email". Openmap.bbn.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ Gardner, P. C. (1981). "A system for the automated office environment". IBM Systems Journal. 20 (3): 321–345. doi:10.1147/sj.203.0321. ISSN 0018-8670; "IBM100 - The Networked Business Place". IBM. August 2, 2020. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Connie Winkler (October 22, 1979). "CompuServe pins hopes on MicroNET, InfoPlex". Computerworld. Vol. 13, no. 42. p. 69; Dylan Tweney (September 24, 1979). "Sept. 24, 1979: First Online Service for Consumers Debuts". Wired.

- ^ Ollig, Mark (October 31, 2011). "They could have owned the computer industry". Herald Journal. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021; "Tech before its time: Xerox's shooting Star computer". New Scientist. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022; "The Xerox Star". toastytech.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "ALL-IN-1". DIGITAL Computing Timeline. January 30, 1998. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "HP Computer Museum". Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ "Retiring the NSFNET Backbone Service: Chronicling the End of an Era" Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, Susan R. Harris, Ph.D., and Elise Gerich, ConneXions, Vol. 10, No. 4, April 1996

- ^ Leiner, Barry M.; Cerf, Vinton G.; Clark, David D.; Kahn, Robert E.; Kleinrock, Leonard; Lynch, Daniel C.; Postel, Jon; Roberts, Larry G.; Wolf, Stephen (1999). "A Brief History of the Internet". arXiv:cs/9901011. Bibcode:1999cs........1011L. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015.

- ^ Rutter, Dorian (2005). From Diversity to Convergence: British Computer Networks and the Internet, 1970-1995 (PDF) (Computer Science thesis). The University of Warwick. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin; Garcia-Swartz, Daniel D (2013). "The History of the Internet: The Missing Narratives". Journal of Information Technology. 28 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1057/jit.2013.4. ISSN 0268-3962. S2CID 41013. SSRN 867087.

- ^ How E-mail Works. howstuffworks.com. 2008. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017.

- ^ "MX Record Explanation" Archived 2015-01-17 at the Wayback Machine, it.cornell.edu

- ^ "What is open relay?". WhatIs.com. Indiana University. July 19, 2004. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Ch Seetha Ram (2010). Information Technology for Management. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 164. ISBN 978-81-8450-267-1.

- ^ Hoffman, Paul (August 20, 2002). "Allowing Relaying in SMTP: A Series of Surveys". IMC Reports. Internet Mail Consortium. Archived from the original on January 18, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c Why Email is Not Instantaneous — and Not Supposed to Be

- ^ The Internet message format is also used for network news

- ^ Simpson, Ken (October 3, 2008). "An update to the email standards". MailChannels Blog Entry. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008.

- ^ J. Klensin (October 2008), "Mail Objects", Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, sec. 2.3.1, doi:10.17487/RFC5321, RFC 5321,

SMTP transports a mail object. A mail object contains an envelope and content. ... The SMTP content is sent in the SMTP DATA protocol unit, and has two parts: the header section and the body.

- ^ D. Crocker (July 2009), "Message Data", Internet Mail Architecture, sec. 4.1, doi:10.17487/RFC5598, RFC 5598,

A message comprises a transit-handling envelope and the message content. The envelope contains information used by the MHS. The content is divided into a structured header and the body.

- ^ P. Resnick, ed. (October 2008). Internet Message Format. IETF Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC5322. RFC 5322. Draft Standard. Obsoletes RFC 2822. Updates RFC 4021. Updated by RFC 6854.

- ^ K. Moore (November 1996). MIME (Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) Part Three: Message Header Extensions for Non-ASCII Text. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC2047. RFC 2047. Draft Standard. Updated by RFC 2184 and 2231. Obsoletes RFC 1590, 1522 and 1521.

- ^ A. Yang; S. Steele; N. Freed (February 2012). Internationalized Email Headers. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6532. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 6532. Proposed Standard. Obsoletes RFC 5335. Updates RFC 2045.

- ^ J. Yao; W. Mao (February 2012). SMTP Extension for Internationalized Email. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6531. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 6531. Proposed Standard. Obsoletes RFC 5336.

- ^ "Now, get your email address in Hindi - The Economic Times". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Resnick, P, ed. (October 2008). "Field Definitions". Internet Message Format. sec. 3.6. doi:10.17487/RFC5322. RFC 5322. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ Resnick, P, ed. (October 2008). "Identification Fields". Internet Message Format. sec. 3.6.4. doi:10.17487/RFC5322. RFC 5322. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ M. Duerst (December 2007). The Archived-At Message Header Field. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC5064. RFC 5064. Proposed Standard.

- ^ Microsoft, Auto Response Suppress, 2010, Microsoft reference Archived 2011-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2010 Sep 22

- ^ John Klensin (October 2008). "Trace Information". Simple Mail Transfer Protocol. IETF. sec. 4.4. doi:10.17487/RFC5321. RFC 5321.

- ^ John Levine (January 14, 2012). "Trace headers". email message. IETF. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

there are many more trace fields than those two

- ^ This extensible field is defined by RFC 7001, this also defines an IANA registry of Email Authentication Parameters.

- ^ RFC 7208.

- ^ D. Crocker; T. Hansen; M. Kucherawy, eds. (September 2011). DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) Signatures. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6376. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 6376. Internet Standard. Updated by RFC 8301, 8463, 8553 and 8616. Obsoletes RFC 4871 and 5672.

- ^ Defined in RFC 3834, and updated by RFC 5436.

- ^ RFC 5518.

- ^ Craig Hunt (2002). TCP/IP Network Administration. O'Reilly Media. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-596-00297-8.

- ^ "What is unicode?". Konfinity. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ "Email policies that prevent viruses". Advosys Consulting. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Problem Solving: Sending Messages in Plain Text". RootsWeb HelpDesk. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

When posting to a RootsWeb mailing list, your message should be sent as "plain text."

- ^ "OpenBSD Mailing Lists". OpenBSD. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

Plain text, 72 characters per line

- ^ "Verhindern, dass die Datei "Winmail.dat" an Internetbenutzer gesendet wird" [How to Prevent the Winmail.dat File from Being Sent to Internet Users]. Microsoft Support. July 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ In practice, some accepted messages may nowadays not be delivered to the recipient's InBox, but instead to a Spam or Junk folder which, especially in a corporate environment, may be inaccessible to the recipient

- ^ "View only unread messages". support.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Free Email Providers in the Yahoo! Directory". dir.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014.

- ^ RFC 2368 section 3 : by Paul Hoffman in 1998 discusses operation of the "mailto" URL.

- ^ a b Hansen, Derek; Smith, Marc A.; Heer, Jeffrey (2011). "E-Mail". In Barnett, George A (ed.). Encyclopedia of social networks. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage. p. 245. ISBN 9781412994170. OCLC 959670912.

- ^ "Creating hyperlinks § E-mail links". MDN Web Docs. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Allen, David (2004). Windows to Linux. Prentice Hall. p. 192. ISBN 978-1423902454. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016.

- ^ "Implementation and Operation". DISTRIBUTED ELECTRONIC MAIL MODELS IN IMAP4. sec. 4.5. doi:10.17487/RFC1733. RFC 1733.

- ^ "Message Store (MS)". Internet Mail Architecture. sec. 4.2.2. doi:10.17487/RFC5598. RFC 5598.

- ^ By Om Malik, GigaOm. "Is Email a Curse or a Boon? Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine" September 22, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ Martin, Brett A. S.; Van Durme, Joel; Raulas, Mika; Merisavo, Marko (2003). "E-mail Marketing: Exploratory Insights from Finland" (PDF). Journal of Advertising Research. 43 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1017/s0021849903030265. ISSN 0021-8499. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2012.

- ^ Lev, Amir (October 2, 2009). "Spam culture, part 1: China". Archived from the original on November 10, 2016.

- ^ "Email Is Top Activity On Smartphones, Ahead Of Web Browsing & Facebook [Study]". March 28, 2013. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014.

- ^ "The ultimate mobile email statistics overview". Archived from the original on July 11, 2014.

- ^ Richtel, Matt (December 20, 2010). "E-Mail Gets an Instant Makeover". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Gustini, Ray (December 21, 2010). "Why Are Young People Abandoning Email?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Perez, Sarah (March 24, 2016). "Email is dying among mobile's youngest users". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Suneja, Bharat (September 10, 2007). "Set Message Size Limits in Exchange 2010 and Exchange 2007". Exchangepedia. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013.

- ^ Humphries, Matthew (June 29, 2009). "Google updates file size limits for Gmail and YouTube". Geek.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011.

- ^ "Maximum attachment size", Gmail Help. Archived October 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Walther, Henrik (January 2009). "Mysterious Attachment Size Increases, Replicating Public Folders, and More". TechNet Magazine. Retrieved November 7, 2021 – via Microsoft Docs. Exchange Queue & A.

- ^ "Send large files to other people" Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine, Microsoft.com

- ^ "8 ways to email large attachments" Archived 2016-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Chris Hoffman, December 21, 2012, makeuseof.com

- ^ Radicati, Sara. "Email Statistics Report, 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 1, 2011.

- ^ Gross, Doug (October 20, 2010). "Happy Information Overload Day!". CNN. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ Stross, Randall (April 20, 2008). "Struggling to Evade the E-Mail Tsunami". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ "Seeing Spam? How To Take Care of Your Google Analytics Data". sitepronews.com. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ Rich Kawanagh. The top ten email spam list of 2005. ITVibe news, 2006, January 02, ITvibe.com Archived 2008-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ How Microsoft is losing the war on spam Salon.com Archived 2008-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spam Bill 2003 (PDF Archived 2006-09-11 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Google Says Its AI Catches 99.9 Percent of Gmail Spam" Archived 2016-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, Cade Metz, July 09 2015, wired.com

- ^ "Spam and phishing in Q1 2016" Archived 2016-08-09 at the Wayback Machine, May 12, 2016, securelist.com

- ^ "Kaspersky Lab Spam and Phishing report". May 26, 2021. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "2021 Email Usage Statistics". October 5, 2021. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Waichulis, Arin (April 5, 2024). "Security Bite: iCloud Mail, Gmail, others shockingly bad at detecting malware, study finds". 9to5Mac. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "When are email attachments safe to open?". Cloudflare. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Griffiths, James (May 2, 2020). "How a badly-coded computer virus caused billions in damage | CNN Business". CNN. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ French, Laura (May 14, 2024). "LockBit ransomware spread in millions of emails via Phorpiex botnet". SC Media. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ SMEmail – A New Protocol for the Secure E-mail in Mobile Environments, Proceedings of the Australian Telecommunications Networks and Applications Conference (ATNAC'08), pp. 39–44, Adelaide, Australia, Dec. 2008.

- ^ "When Email Exchanges Become Binding Contracts". law.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Catarina, Jessica; Feitel, Jesse (2019). "Inadvertent Contract Formation via Email under New York Law: An Update" (PDF). Syracuse Law Review. 69.

- ^ Corfield, Gareth (September 30, 2019). "UK court ruling says email signature blocks can sign binding contracts". The Register. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ S. Kiesler; D. Zubrow; A.M. Moses; V. Geller (1985). "Affect in computer-mediated communication: an experiment in synchronous terminal-to-terminal discussion". Human-Computer Interaction. 1: 77–104. doi:10.1207/s15327051hci0101_3.

- ^ Barrett, Grant (December 23, 2007). "All We Are Saying". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ^ "Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs) | Registry.In". registry.in. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ "Made In India 'Datamail' Empowers Russia With Email Address In Russian Language - Digital Conqueror". December 7, 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017.

- ^ RFC 3885, SMTP Service Extension for Message Tracking

- ^ RFC 3888, Message Tracking Model and Requirements

- ^ Amy Harmon (November 22, 2000). "Software That Tracks E-Mail Is Raising Privacy Concerns". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "About.com". Email.about.com. December 19, 2013. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ "Outlook: Web Bugs & Blocked HTML Images" Archived 2015-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, slipstick.com

- ^ "Gmail blows up e-mail marketing..." Archived 2017-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, Ron Amadeo, Dec 13 2013, Ars Technica

Further reading

[edit]- Cemil Betanov, Introduction to X.400, Artech House, ISBN 0-89006-597-7.

- Marsha Egan, "Inbox Detox and The Habit of Email Excellence Archived May 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine", Acanthus Publishing ISBN 978-0-9815589-8-1

- Lawrence Hughes, Internet e-mail Protocols, Standards and Implementation, Artech House Publishers, ISBN 0-89006-939-5.

- Kevin Johnson, Internet Email Protocols: A Developer's Guide, Addison-Wesley Professional, ISBN 0-201-43288-9.

- Pete Loshin, Essential Email Standards: RFCs and Protocols Made Practical, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-34597-0.

- Partridge, Craig (April–June 2008). "The Technical Development of Internet Email" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 30 (2): 3–29. doi:10.1109/mahc.2008.32. ISSN 1934-1547. S2CID 206442868. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2016.

- Sara Radicati, Electronic Mail: An Introduction to the X.400 Message Handling Standards, Mcgraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-051104-7.

- John Rhoton, Programmer's Guide to Internet Mail: SMTP, POP, IMAP, and LDAP, Elsevier, ISBN 1-55558-212-5.

- John Rhoton, X.400 and SMTP: Battle of the E-mail Protocols, Elsevier, ISBN 1-55558-165-X.

- David Wood, Programming Internet Mail, O'Reilly, ISBN 1-56592-479-7.

External links

[edit]- IANA's list of standard header fields

- The History of Email is Dave Crocker's attempt at capturing the sequence of 'significant' occurrences in the evolution of email; a collaborative effort that also cites this page.

- The History of Electronic Mail is a personal memoir by the implementer of an early email system

- A Look at the Origins of Network Email is a short, yet vivid recap of the key historical facts

- Business E-Mail Compromise - An Emerging Global Threat, FBI

- Explained from first principles, a 2021 article attempting to summarize more than 100 RFCs

Terminology and Concepts

Definitions and Etymology

Email, short for electronic mail, refers to the exchange of digital messages between computer users over a communications network, such as the Internet, using standardized protocols to ensure reliable delivery and retrieval.[4] This system enables asynchronous communication, where messages are stored on servers until the recipient accesses them, distinguishing it from real-time methods.[8] The term "electronic mail" originated in the early 1970s amid the rise of networked computing, with Ray Tomlinson credited for implementing the first networked email system in 1971 while working on ARPANET.[9] The abbreviation "email" (or "e-mail") first appeared in print in 1979 and became common in the 1980s, reflecting the technology's evolution from time-sharing systems to widespread internet use.[10] Developers chose "electronic mail" to parallel traditional postal services, emphasizing structured delivery and addressing to make the concept accessible to non-technical users. Email differs from postal mail, which relies on physical transport and can take days, by providing near-instantaneous digital transmission without tangible media.[8] In contrast to instant messaging, which supports synchronous, conversation-like exchanges often requiring both parties to be online simultaneously, email allows deferred reading and attachment of files or multimedia.[11] Short Message Service (SMS), meanwhile, is constrained to brief texts via cellular networks, lacking email's capacity for complex formatting or long-form content.[12] Many email-specific terms draw from postal analogies to aid user familiarity. "Inbox" and "outbox" mimic physical trays for incoming and outgoing correspondence in office mailrooms, a convention established in early email software to simulate interoffice memo handling.[13] The term "spam," denoting unsolicited bulk messages, stems from a 1970 Monty Python comedy sketch where the word "Spam" is repeated incessantly, a metaphor first applied to disruptive online posts in 1980s multi-user dungeons (MUDs) and later to email in the early 1990s.[14]Core Components

An email system relies on several interconnected core components to facilitate the composition, submission, transfer, storage, and retrieval of messages. At its foundation, the sender's device hosts a Message User Agent (MUA), which serves as the interface for composing and submitting emails. This client software interacts with a Mail Submission Agent (MSA) to initiate the process, ensuring messages are properly formatted and authenticated before entering the network.[8] On the recipient side, a corresponding Recipient MUA (rMUA) enables the viewing and management of incoming messages, typically after retrieval from a remote server.[8] Central to the system's operation are the message servers, which handle the intermediary roles of transfer and delivery. Message Transfer Agents (MTAs) act as relays, routing emails across networks by examining addresses and forwarding them hop-by-hop without modifying the content, except for adding trace information. Mail Delivery Agents (MDAs), in turn, perform the final deposition of messages into designated storage. These server-based components operate within Administrative Management Domains (ADMDs), distinguishing local ecosystems—such as intra-organizational handling within a single domain—from remote ones that span multiple domains and require boundary relays for secure handoff.[8] Email addresses play a pivotal role in this architecture, structured in the format<local-part>@<domain>, where the local-part identifies a specific mailbox within the domain, and the domain specifies the responsible ADMD for routing and delivery. Domains are resolved globally via the Domain Name System (DNS), enabling accurate navigation through the decentralized network. Mailboxes function as digital repositories within a Message Store (MS) on the recipient's server, holding incoming messages until accessed by the rMUA; they also support storage for outgoing drafts or sent items on the sender's side. This separation underscores the conceptual divide between local components, like an individual's MUA on their device, and remote ones, such as MTAs and MDAs hosted on infrastructure servers.[8]