Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

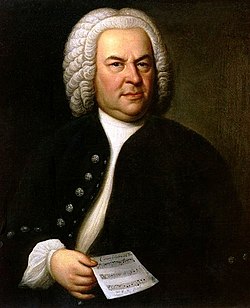

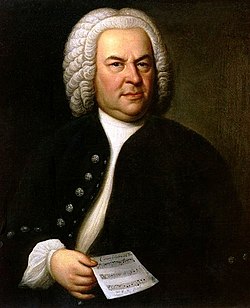

Johann Sebastian Bach

View on Wikipedia

Johann Sebastian Bach[n 1] (31 March [O.S. 21 March] 1685 – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety of instruments and forms, including the orchestral Brandenburg Concertos; solo instrumental works such as the cello suites and sonatas and partitas for solo violin; keyboard works such as the Goldberg Variations and The Well-Tempered Clavier; organ works such as the Schübler Chorales and the Toccata and Fugue in D minor; and choral works such as the St Matthew Passion and the Mass in B minor. Since the 19th-century Bach Revival, he has been widely regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music.

Key Information

The Bach family had already produced several composers when Johann Sebastian was born as the last child of a city musician, Johann Ambrosius, in Eisenach. After being orphaned at age 10, he lived for five years with his eldest brother, Johann Christoph, then continued his musical education in Lüneburg. In 1703 he returned to Thuringia, working as a musician for Protestant churches in Arnstadt and Mühlhausen. Around that time he also visited for longer periods the courts in Weimar, where he expanded his organ repertory, and the reformed court at Köthen, where he was mostly engaged with chamber music. By 1723 he was hired as Thomaskantor (cantor with related duties at St Thomas School) in Leipzig. There he composed music for the principal Lutheran churches of the city and Leipzig University's student ensemble, Collegium Musicum. In 1726 he began publishing his organ and other keyboard music. In Leipzig, as had happened during some of his earlier positions, he had difficult relations with his employer. This situation was somewhat remedied when his sovereign, Augustus III of Poland, granted him the title of court composer of the Elector of Saxony in 1736. In the last decades of his life, Bach reworked and extended many of his earlier compositions. He died due to complications following eye surgery in 1750 at the age of 65. Four of his twenty children, Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel, Johann Christoph Friedrich, and Johann Christian, became composers.

Bach enriched established German styles through his mastery of counterpoint, harmonic and motivic organisation, and his adaptation of rhythms, forms, and textures from abroad, particularly Italy and France. His compositions include hundreds of cantatas, both sacred and secular. He composed Latin church music, Passions, oratorios, and motets. He adopted Lutheran hymns, not only in his larger vocal works but also in such works as his four-part chorales and his sacred songs. Bach wrote extensively for organ and other keyboard instruments. He composed concertos, for instance for violin and for harpsichord, and suites, as chamber music as well as for orchestra. Many of his works use contrapuntal techniques like canon and fugue.

Several decades after the end of his life, in the 18th century, Bach was still primarily known as an organist. By 2013, more than 150 recordings had been made of his The Well-Tempered Clavier. Several biographies of Bach were published in the 19th century, and by the end of that century all of his known music had been printed.[5] Dissemination of Bach scholarship continued through periodicals (and later also websites) devoted to him, other publications such as the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV, a numbered catalogue of his works), and new critical editions of his compositions. His music was further popularised by a multitude of arrangements, including the "Air on the G String" and "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring", and recordings, among them three different box sets of performances of his complete oeuvre marking the 250th anniversary of his death.

Early life, marriages, and education

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach, the capital of the duchy of Saxe-Eisenach, in present-day Germany, on 21 March 1685 O.S.[7][8][n 2] He was the eighth and youngest child of Johann Ambrosius Bach, the director of the town musicians, and Maria Elisabeth née Lämmerhirt, daughter of a town councillor.[10][11][12] The Bach family, traditionally traced to the patriarch Vitus "Veit" Bach (d. 1619), produced three to four generations of musicians in the Thuringia region, whose insular cultural climate fostered conservative musicianship, with external influences arriving mainly via the courts.[13] Nothing is definitively known about Bach's early years before 1693; his musical education in particular is highly conjectural.[10] His family, particularly the uncles, were all professional musicians who worked as church organists, court chamber musicians, and composers.[14] Bach's father presumably taught him the violin, Ambrosius' own primary instrument, along with basic music theory principles.[15][16] One uncle, Johann Christoph Bach (1645–1693) may have introduced him to the organ, though this is debated since the uncle may not have been close to the immediate family.[15][16]

Bach's mother died in 1694, and his father eight months later in February 1695.[17] The 10-year-old Bach moved in with his eldest brother, Johann Christoph Bach (1671–1721), the organist at St Michael's Church in Ohrdruf, Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.[18] There he studied, performed, and copied music, including his brother's, despite being forbidden to do so because scores were so valuable and private and ledger paper was costly.[19][20] From his brother he also received instruction on the clavichord. Johann Christoph exposed him to the works of composers of the day, including South Germans such as Johann Caspar Kerll, Johann Jakob Froberger, and Johann Pachelbel (under whom Johann Christoph had studied); North Germans such as Georg Böhm, Johann Reincken and Friedrich Nicolaus Bruhns from Hamburg, and Dieterich Buxtehude;[21] Frenchmen such as Jean-Baptiste Lully, Louis Marchand, and Marin Marais;[22] and the Italian Girolamo Frescobaldi.[23] He learned theology, Latin, and Greek at the local gymnasium.[24]

By 3 April 1700 Bach and his school friend Georg Erdmann—who was two years older—began studies at St Michael's School in Lüneburg, two weeks' travel north of Ohrdruf.[25][26] Their journey was probably undertaken mostly on foot.[26] He sang in the choir and had opportunities to pursue his interest in instrumental music:[27] recently, evidence has come to light that he received organ lessons.[28] He also came into contact with sons of aristocrats from northern Germany who had been sent to the nearby Ritter-Academie to prepare for careers in other disciplines.[29]

Marriages and children

[edit]Four months after arriving at Mühlhausen in 1707, Bach married Maria Barbara Bach, his second cousin.[27] Later that year their first child, Catharina Dorothea, was born, and Maria Barbara's elder, unmarried sister joined them. She remained to help run the household until she died in 1729. Three sons were also born: Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel, and Johann Gottfried Bernhard. All became musicians, and the first two composers. Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara had seven children. Their twins born in 1713 died within a year, and their last son, Leopold, also died within a year of his birth.[30] On 7 July 1720, while Bach was away in Carlsbad with Prince Leopold, Maria Barbara suddenly died.[31] The next year, he met Anna Magdalena Wilcke, a gifted soprano 16 years his junior, while she was performing at the court in Köthen; they married on 3 December 1721.[32] Together they had 13 children, six of whom survived into adulthood: Gottfried Heinrich; Elisabeth Juliane Friederica (1726–1781); Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, who both became musicians; Johanna Carolina (1737–1781); and Regina Susanna (1742–1809).[33]

Career

[edit]Weimar, Arnstadt, and Mühlhausen (1703–1708)

[edit]

In January 1703, shortly after graduating from St. Michael's in 1702 and being turned down for the post of organist at Sangerhausen,[34] Bach was appointed court musician in the chapel of Duke Johann Ernst III in Weimar.[35] His role there is unclear, but it probably included menial, non-musical duties. During his seven-month tenure at Weimar, his reputation as a keyboardist spread so widely that he was invited to inspect the new organ and give the inaugural recital at the New Church (now Bach Church) in Arnstadt, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) southwest of Weimar.[36] On 14 August 1703 he became the organist at the New Church,[16] with light duties, a relatively generous salary, and a new organ tuned in a temperament that allowed music written in a wider range of keys to be played.[37]

Despite a musically enthusiastic employer, tension built up between Bach and his employer after several years in the post. For example, Bach upset his employer with a prolonged absence from Arnstadt: after obtaining leave for four weeks, he was absent for around four months in 1705–1706 to take lessons from the organist and composer Johann Adam Reincken and to hear him and Dieterich Buxtehude play in the northern city of Lübeck.[38] The visit to Buxtehude and Reincken involved a 450-kilometre (280 mi) journey each way, reportedly on foot.[39][40] Buxtehude probably introduced Bach to his friend Reincken so that he could learn from his compositional technique (especially his mastery of fugue), his organ playing and his skills with improvisation. Bach knew Reincken's music very well; he copied Reincken's monumental An Wasserflüssen Babylon when he was 15 years old. Bach later wrote several other works on the same theme. When Bach revisited Reincken in 1720 and showed him his improvisatory skills on the organ, Reincken reportedly remarked: "I thought that this art was dead, but I see that it lives in you."[41]

In 1706 Bach applied for a post as organist at the Blasius Church in Mühlhausen.[42][43] As part of his application, he had a cantata performed at Easter, 24 April 1707, that resembles his later Christ lag in Todes Banden BMV 4.[44] Bach's application was accepted a month later, and he took up the post in July.[42] The position included higher remuneration, improved conditions, and a better choir. Bach persuaded the church and town government at Mühlhausen to fund an expensive renovation of the organ at the Blasius Church. In 1708 Bach wrote Gott ist mein König, a festive cantata for the inauguration of the new council, which was published at the council's expense.[27][45] This was the only extant Bach cantata published in his lifetime.[46]

Return to Weimar (1708–1717)

[edit]

Bach left Mühlhausen in 1708, returning to Weimar this time as organist and from 1714 Konzertmeister (director of music) at the ducal court, where he could work with a large, well-funded contingent of professional musicians.[27] Bach and his wife moved into a house near the ducal palace.[47] Bach's time in Weimar began a sustained period of composing keyboard and orchestral works. He attained the proficiency and confidence to extend the prevailing structures and include influences from abroad. He learned to write dramatic openings and employ the dynamic rhythms and harmonic schemes used by Italians such as Vivaldi, Corelli, and Torelli. Bach absorbed these stylistic aspects to a certain extent by transcribing Vivaldi's string and wind concertos for harpsichord and organ. He was particularly attracted to the Italian style, in which one or more solo instruments alternate section-by-section with the full orchestra throughout a movement.[48]

In Weimar Bach continued to play and compose for the organ and perform concert music with the duke's ensemble.[27] He also began to write the preludes and fugues that were later assembled into the first volume of The Well-Tempered Clavier ("clavier" meaning clavichord or harpsichord),[49] which eventually comprised two volumes written over 20 years,[50] each containing 24 pairings of preludes and fugues in every major and minor key. In Weimar, Bach also started work on the Little Organ Book, containing traditional Lutheran chorale tunes set in complex textures. In 1713 Bach was offered a post in Halle when he advised the authorities during a renovation by Christoph Cuntzius of the main organ in the west gallery of the Market Church of Our Dear Lady.[51][52]

In early 1714 Bach was promoted to Konzertmeister, an honour that entailed performing a church cantata monthly in the castle church.[53] The first three cantatas in the new series Bach composed in Weimar were Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 182, for Palm Sunday, which coincided with the Annunciation that year; Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12, for Jubilate Sunday; and Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172, for Pentecost.[54] Bach's first Christmas cantata, Christen, ätzet diesen Tag, BWV 63, premiered in 1714 or 1715.[55][56] In 1717 Bach fell out of favour in Weimar and, according to the court secretary's report, was jailed for almost a month before being unfavourably dismissed: "On November 6, [1717,] the quondam [former] concertmaster and organist Bach was confined to the County Judge's place of detention for too stubbornly forcing the issue of his dismissal and finally on December 2 was freed from arrest with notice of his unfavourable discharge."[57]

Köthen (1717–1723)

[edit]

Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, hired Bach to serve as his Kapellmeister (director of music) in 1717. Himself a musician, Leopold appreciated Bach's talents, paid him well, and gave him considerable latitude in composing and performing. Leopold was a Calvinist and thus did not use elaborate music in his form of worship, so most of Bach's work from this period is secular,[58] including the orchestral suites, cello suites, sonatas and partitas for solo violin, and the Brandenburg Concertos.[59] Bach also composed secular cantatas for the court, such as Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a.[60]

Despite George Frideric Handel being born in the same year and only about 130 kilometres (80 mi) apart, Bach never met his celebrated contemporary. In 1719, Bach made the 35-kilometre (22 mi) journey from Köthen to Halle with the intention to meet Handel, but Handel had left town.[61][62] In 1730, Bach's oldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, travelled to Halle to invite Handel to visit the Bach family in Leipzig, but the visit did not take place.[63]

Leipzig (1723–1750)

[edit]Leipzig was "the leading cantorate in Protestant Germany",[64] located in the mercantile city in the Electorate of Saxony. In 1723, Bach was appointed Thomaskantor (director of church music) in Leipzig. He was responsible for directing the St Thomas School and for providing four churches with music, the St Thomas Church, the St Nicholas Church, and to a lesser extent, the New Church and St Peter's Church.[65] Bach held the position for 27 years, until his death. During that time, he gained further prestige through honorary appointments at the courts of Köthen and Weissenfels, as well as that of the Elector Frederick Augustus (who was also King of Poland) in Dresden.[64] Bach frequently disagreed with his employer, Leipzig's city council, whom he regarded as "penny-pinching".[66]

Appointment in Leipzig

[edit]

Johann Kuhnau had been Thomaskantor in Leipzig from 1701 until his death on 5 June 1722. Bach had visited Leipzig during Kuhnau's tenure: in 1714 he attended the service at the St. Thomas Church on the first Sunday of Advent,[67] and in 1717 he had tested the organ of the St. Paul's Church.[68] In 1716 Bach and Kuhnau met on the occasion of the testing and inauguration of an organ in Halle.[52] The position was offered to Bach only after it had been offered to Georg Philipp Telemann and then Christoph Graupner—both of whom chose to stay where they were, Telemann in Hamburg and Graupner in Darmstadt—after using the Leipzig offer to negotiate better terms of employment.[69][70] Bach was required to instruct the Thomasschule students in singing and provide music for Leipzig's main churches. He was also assigned to teach Latin, but was allowed to employ four "prefects" (deputies) to do this instead. The prefects also aided with musical instruction.[71] A cantata was required for the church services on each Sunday and additional church holidays during the liturgical year.[72]

Cantata cycle years (1723–1729)

[edit]Bach usually led performances of his cantatas, most composed within three years of his relocation to Leipzig. He assumed the office of Thomaskantor on 30 May 1723, presenting the first new cantata, Die Elenden sollen essen, BWV 75, in the St. Nicholas Church on the first Sunday after Trinity.[73] Bach collected his cantatas in annual cycles, with the first starting in 1723. Five are mentioned in obituaries, and three are extant.[54] Of the more than 300 cantatas he composed in Leipzig, over 100 have been lost.[74] Most of these works expound on the Gospel readings prescribed for every Sunday and feast day in the Lutheran year. Bach started a second annual cycle on the first Sunday after the Trinity of 1724 and composed only chorale cantatas, each based on a single church hymn. These include O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort, BWV 20, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62, and Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 1.[75]

Bach drew the soprano and alto choristers from the school and the tenors and basses from the school and elsewhere in Leipzig. Performing at weddings and funerals provided extra income for these groups; probably for this purpose, and for in-school training, he wrote at least six motets, such as BWV 227.[76] As part of his regular church work, he performed other composers' motets, which served as formal models for his own.[77] Bach's predecessor as cantor, Johann Kuhnau, had also been music director for the Paulinerkirch (St Paul's Church), the church of Leipzig University. But when Bach was installed as cantor in 1723, he was put in charge only of music for church holiday services at the Paulinerkirch; his request to also provide music for regular Sunday services there for an added fee was denied.

In 1725 Bach "lost interest" in working even for festal services at the Paulinerkirch and decided to appear there only on "special occasions".[78] The Paulinerkirch had a much better and newer (1716) organ than the St Thomas Church or the St Nicholas Church.[79] Bach was not required to play any organ in his official duties, but it is believed he liked to play on the Paulinerkirch organ for his own pleasure.[80] Bach's last newly composed chorale cantata in his second year (his second annual cycle for cantata composition) in Leipzig was Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 1, for the feast of the Annunciation on 25 March, which fell on Palm Sunday in 1725. Of the chorale cantatas composed before Palm Sunday 1725, only K 77, 84, 89, 95, 96, and 109 (BWV 135, 113, 130, 80, 115, and 111) were not included in the chorale cantata cycle that was still extant in Leipzig in 1830.[81]

Bach broadened his composing and performing beyond the liturgy by taking over, in March 1729, the directorship of the Collegium Musicum, a secular performance ensemble Telemann had started. This was one of the dozens of private societies in the major German-speaking cities established by musically active university students; they had become increasingly important in public musical life and were typically led by the most prominent professionals in a city. In the words of Christoph Wolff, assuming the directorship was a shrewd move that "consolidated Bach's firm grip on Leipzig's principal musical institutions".[82] Every week, the Collegium Musicum gave two-hour performances, in winter at the Café Zimmermann, a coffeehouse on Catherine Street off the main market square, and in summer in the owner Gottfried Zimmerman's outdoor coffee garden just outside the town walls, near the East Gate. The concerts, all free of charge, ended with Zimmermann's death in 1741. Apart from showcasing his earlier orchestral repertoire, such as the Brandenburg Concertos and orchestral suites, many of Bach's newly composed or reworked pieces were performed for these venues, including parts of his Clavier-Übung (Keyboard Practice), his violin and keyboard concertos, and the Coffee Cantata.[27][83]

Middle years in Leipzig (1730–1739)

[edit]Before starting on the Gospel of Mark after 1730, Bach had composed the St John Passion and the St Matthew Passion; the St Matthew Passion was first performed on Good Friday 11 April 1727.[84] The 1731 St Mark Passion (German: Markus-Passion), BWV 247, is a lost Passion setting by Bach, first performed in Leipzig on Good Friday, 23 March 1731. Though Bach's music is lost, the libretto by Picander is extant, and the work can to some degree be reconstructed from it.[85] In 1733 Bach composed a Kyrie–Gloria Mass in B minor for the court in Dresden, which had become Catholic, that he later used in his Mass in B minor. He presented the manuscript to the Elector in a successful bid to persuade the prince to give him the title of Court Composer.[86] He later extended this work into a full mass by adding a Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei, the music for which was partly based on his own cantatas and partly original. Bach's appointment as Court Composer was part of his long struggle to achieve greater bargaining power with the Leipzig council.

Bach composed his Christmas Oratorio for the 1734–35 Christmas season in Leipzig, by using works he had already composed such as the Christmas cantatas and other church music for all seven occasions of the Christmas season including part of his Weimar cantata cycle and Christen, ätzet diesen Tag, BWV 63.[87] In 1735 Bach started preparing his first organ music publication, which was printed as the third Clavier-Übung in 1739.[88] From around that year he started to compile and compose the set of preludes and fugues for harpsichord that became the second book of The Well-Tempered Clavier.[89] He received the title of "Royal Court Composer" from Augustus III in 1736.[86][17] Between 1737 and 1739 Bach's former pupil Carl Gotthelf Gerlach held the directorship of the Collegium Musicum.[90]

Final years (1740–1750)

[edit]From 1740 to 1748 Bach copied, transcribed, expanded or programmed music in an older polyphonic style (stile antico) by, among others, Palestrina (BNB I/P/2),[91] Kerll (BWV 241),[92] Torri (BWV Anh. 30),[93] Bassani (BWV 1081),[94] Gasparini (Missa Canonica),[95] and Caldara (BWV 1082).[96] Bach's style shifted in the last decade of his life, showing an increased integration of elements of the stile antico, including polyphonic structures and canons.[97] His fourth and last Clavier-Übung volume, the Goldberg Variations for two-manual harpsichord, contains nine canons and was published in 1741.[98] During this period, Bach also continued to adapt music of contemporaries such as Handel (BNB I/K/2)[99] and Stölzel (BWV 200),[100] and gave many of his own earlier compositions, such as the St Matthew and St John Passions and the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes,[101] their final revisions. He also programmed and adapted music by composers of a younger generation, including Pergolesi (BWV 1083),[102] and his own students, such as Goldberg (BNB I/G/2).[103]

In 1746 Bach was preparing to enter Lorenz Christoph Mizler's Society of Musical Sciences.[104] To be admitted, he had to submit a composition. He chose his Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch da komm' ich her", and a portrait painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann that featured Bach's Canon triplex á 6 Voc.[105] In May 1747, Bach visited the court of King Frederick II of Prussia in Potsdam. The king played a theme for Bach and challenged him to improvise a fugue based on it. Bach obliged, playing a three-part fugue on one of Frederick's early prototypes of a fortepiano,[106] a new type of instrument at the time. Upon his return to Leipzig he composed a set of fugues and canons and a trio sonata based on the Thema Regium ("King's Theme"). Within a few weeks this music was published as The Musical Offering and dedicated to Frederick. The Schübler Chorales, a set of six chorale preludes transcribed from cantata movements Bach had written two decades earlier, were published within a year.[107][108] Around the same time, the set of five canonic variations Bach had submitted when entering Mizler's society in 1747 were also printed.[109]

Two large-scale compositions occupied a central place in Bach's last years. Beginning around 1742 he wrote and revised the various canons and fugues of The Art of Fugue, which he continued to prepare for publication until shortly before his death.[110][111] After extracting a cantata, BWV 191 from his 1733 Kyrie-Gloria Mass for the Dresden court in the mid-1740s, Bach expanded that setting into his Mass in B minor in the last years of his life. The complete mass was not performed during his lifetime. It is considered among the greatest choral works in history.[112] In January 1749, with Bach in declining health, his daughter Elisabeth Juliane Friederica married his pupil Johann Christoph Altnickol. On 2 June Heinrich von Brühl wrote to one of the Leipzig burgomasters to request that his music director, Gottlob Harrer, fill the Thomaskantor and Director musices posts "upon the eventual ... decease of Mr. Bach".[113] His eyesight failing, Bach underwent eye surgery in March 1750 and again in April by the British eye surgeon John Taylor, a man widely understood today as a charlatan and believed to have blinded hundreds of people.[114]

Death and burial

[edit]Bach died on 28 July 1750 from complications due to unsuccessful eye surgery.[115] He had a stroke a few days before his death.[116][117][118] He was originally buried at Old St John's Cemetery in Leipzig, where his grave went unmarked for nearly 150 years. In 1894, his remains were found and moved to a vault in St John's Church. This building was destroyed by Allied bombing during the Second World War, and in 1950 Bach's remains were taken to their present grave in St Thomas Church.[27] Later research has called into question whether the remains in the grave are actually Bach's.[119]

An inventory drawn up a few months after Bach's death shows that his estate included five harpsichords, two lute-harpsichords, three violins, three violas, two cellos, a viola da gamba, a lute, a spinet, and 52 "sacred books", including works by Martin Luther and Josephus.[120] C. P. E. Bach saw to it that The Art of Fugue, though unfinished, was published in 1751.[121] Together with one of J. S. Bach's former students, Johann Friedrich Agricola, C. P. E. Bach also wrote the obituary ("Nekrolog"), which was published in Mizler's Musikalische Bibliothek, a periodical journal produced by the Society of Musical Sciences, in 1754.[109]

Music

[edit]| Lists of |

| Compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach |

|---|

Antecedents and influences

[edit]In addition to his study of German composers and without visiting France or Italy, Bach absorbed influences from French and Italian music. From an early age, Bach studied the works of his musical contemporaries of the Baroque period and those of earlier generations, and those influences are reflected in his music.[122]

Italian influences including Weimar concerto transcriptions

[edit]The court at Weimar was particularly interested in Italian music. There have been questions of attribution about some of the music Bach was exposed to there, but Antonio Vivaldi was certainly an important influence on him. In particular, Bach borrowed the idea of propulsive rhythmic patterns.[123][124]

- The model for BWV 974 has been variously attributed to Vivaldi, Benedetto Marcello, and Alessandro Marcello. In the second half of the 20th century, the oboe concerto that was the model for Bach's transcription was attributed to Allesandro Marcello again—as it had been in its 1717 printed edition—through research of scholars such as Eleanor Selfridge-Field.[125][126][127]

- The model for BWV 979 has been attributed to Vivaldi and to Giuseppe Torelli. Listed as No. 10 in the Anhang (Appendix) of the Ryom-Verzeichnis (RV), it was generally attributed to Torelli. Federico Maria Sardelli argued against the attribution to Torelli, and in favour of an attribution to Vivaldi, in an article published in 2005. Consequently, the concerto was relisted as RV 813. The composition originated before 1711: its seven movements and second viola part are not compatible with Vivaldi's later style.[124][128][129]

- No models have been identified for BWV 977, 983, and 986. Stylistically BWV 977 is more Italianate than BWV 983 and 986. David Schulenberg supposes an Italian model for BWV 977, and German models for the other two concertos.[130]

Bach realised his other transcriptions of Vivaldi concertos after versions circulating as manuscript. Later versions of some of these were published in his Op. 4 and 7:

- After Vivaldi's Violin Concerto in B-flat major (later version published as Op. 4 No. 1, RV 383a): Concerto in G major, BWV 980 (harpsichord)[123]

- After Vivaldi's Violin Concerto in G minor, RV 316 (later version published as Op. 4 No. 6, RV 316a): Concerto in G minor, BWV 975 (harpsichord)[123]

- After Vivaldi's Violin Concerto in G major (later version published as Op. 7 No. 8, RV 299): Concerto in G major, BWV 973 (harpsichord)[123]

- After Vivaldi's Violin Concerto Grosso Mogul in D major, RV 208 (later version published as Op. 7 No. 11, RV 208a): Concerto in C major, BWV 594 (organ)[123]

- After Vivaldi's Violin Concerto in D minor, RV 813 (formerly RV Anh. 10 often attributed to Torelli):[124] Concerto in B minor, BWV 979 (harpsichord)

Bach also used the theme of the first movement of the "Spring" concerto from The Four Seasons for the third movement (aria) of his cantata Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende? BWV 27. Bach was deeply influenced by Vivaldi's concertos and arias (recalled in his St John Passion, St Matthew Passion, and cantatas). According to Christoph Wolff and Walter Emery, Bach transcribed six of Vivaldi's concerti for solo keyboard, three for organ, and one for four harpsichords, strings, and basso continuo (BWV 1065) based on Vivaldi's concerto for four violins, two violas, cello, and basso continuo (RV 580).[16][131]

Arcangelo Corelli's influence in chamber music was not confined to his native Italy; his works were key in the development of the music of an entire generation of composers, including Bach, Vivaldi, Georg Friedrich Handel, and François Couperin. Bach studied Corelli's work and based an organ fugue (BWV 579) on his Opus 3 of 1689. Handel's Opus 6 Concerti Grossi take Corelli's older Opus 6 Concerti as models, rather than the later three-movement Venetian concerto of Vivaldi favoured by Bach.[132]

French influences

[edit]Jean-Baptiste Lully is credited with the invention in the 1650s of the French overture, a form used extensively in the Baroque and Classical eras, especially by Bach and Handel.[133] The later French composer François Couperin has been seen as an influence on the dance-based movements of Bach's keyboard suites.[134] The influence of Lully's music produced a radical revolution in the style and composition of the dances of the French court, which Bach made use of in his music. Instead of the slow and stately movements that had prevailed until Lully began composing, Lully introduced lively ballets of rapid rhythm, often based on well-known dance types such as gavottes, menuets, rigaudons, and sarabandes, forms often used by Bach.[135][136]

Creative range

[edit]

Bach's creative range and musical style encompassed four-part harmony,[137] modulation,[138] ornamentation,[139] use of continuo instruments solos,[140] virtuoso instrumentation,[141] counterpoint,[142] and a refined attention to structure and lyrics.[143][144] Like his contemporaries Handel, Telemann, and Vivaldi, Bach composed concertos, suites, recitatives, da capo arias, and four-part choral music, and employed basso continuo. Most of the prints of Bach's music that appeared during his lifetime were commissioned by the composer.[145] His music is harmonically more innovative than his peers', employing surprisingly dissonant chords and progressions, often extensively exploring harmonic possibilities within one piece.[146]

Bach's hundreds of sacred works are usually seen as manifesting not just his craft but also a deep faith in God.[147][148] His commitment to the Lutheran faith was reflected in his teaching Luther's Small Catechism as the Thomaskantor in Leipzig, and some of his pieces represent it.[149] The Lutheran chorale was the basis of much of his work. In elaborating these hymns into his chorale preludes, he wrote more cogent and tightly integrated works than most, even when they were massive and lengthy.[150][151] The large-scale structure of every major Bach sacred vocal work is evidence of subtle, elaborate planning to create religiously and musically powerful expression.[152] Bach published or carefully compiled in manuscript many collections of pieces that explored the range of artistic and technical possibilities inherent in almost every genre of his time except opera. For example, The Well-Tempered Clavier comprises two books, each of which presents a prelude and fugue in every major and minor key.[153]

Compositional style in the High Baroque

[edit]Four-part harmony

[edit]

Four-part harmony predates Bach, but he lived during a time when modal music in Western tradition was largely supplanted by the tonal system. In this system a piece of music progresses from one chord to the next according to certain rules, with each chord characterised by four notes. The principles of four-part harmony are found not only in Bach's four-part choral music; he also prescribes it for instance in figured bass accompaniment.[137] The new system was at the core of Bach's style. Some examples of this characteristic of Bach's style and its influence:

- When in the 1740s Bach staged his arrangement of Pergolesi's Stabat Mater, he upgraded the viola part (which in the original composition plays in unison with the bass part) to fill in the harmony, thus adapting the composition to four-part harmony.[154]

- When, starting in the 19th century in Russia, there was a discussion about the authenticity of four-part court chant settings compared to earlier Russian traditions, Bach's four-part chorale settings, such as those ending his Chorale cantatas, were considered foreign-influenced models, but such influence was deemed unavoidable.[155]

Bach's insistence on the tonal system and contribution to shaping it did not imply he was less at ease with the older modal system and the genres associated with it: more than his contemporaries (who had "moved on" to the tonal system without much exception), he often returned to the then-antiquated modes and genres. His Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, emulating the chromatic fantasia genre used by earlier composers such as John Dowland and Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck in D Dorian mode (comparable to D minor in the tonal system), is an example. Bach's first biographer, Johann Nikolaus Forkel, wrote of Bach's original approach to this: "I have expended much effort to find another piece of this type by Bach. But it was in vain. This fantasy is unique and has always been second to none."[156]

Modulation

[edit]Modulation, or changing key in the course of a piece, is another style characteristic where Bach goes beyond the norm in his time. Baroque instruments vastly limited modulation possibilities: keyboard instruments, before a workable system of temperament, limited the keys that could be modulated to, and wind instruments, especially brass instruments such as trumpets and horns, about a century before they were fitted with valves and crooks, were tied to the key of their tuning. Bach pushed the limits: he added "strange tones" in his organ playing, confusing the singers, according to an indictment he had to face in Arnstadt,[138] and Louis Marchand, another early experimenter with modulation, seems to have avoided confrontation with Bach because the latter went further than anyone had done before.[157] In the "Suscepit Israel" of his 1723 Magnificat, he had the trumpets in E-flat play a melody in the enharmonic scale of C minor.[158]

The major development in Bach's time to which he contributed in no small way was a temperament for keyboard instruments that allowed their use in every key (12 major and 12 minor) and also modulation without retuning. His Capriccio on the departure of a beloved brother, a very early work, showed a gusto for modulation unlike any contemporary work it has been compared to,[159] but the full expansion came with The Well-Tempered Clavier, using all keys, which Bach apparently had been developing since around 1720, the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach being one of its earliest examples.[160]

Ornamentation

[edit]

The second page of the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach is an ornament notation and performance guide that Bach wrote for his then nine-year-old eldest son. Bach was generally quite specific on ornamentation in his compositions (in his time, much ornamentation was not written out by composers but rather considered a liberty of the performer),[139] and his ornamentation was often quite elaborate. For instance, the "Aria" of the Goldberg Variations has rich ornamentation in nearly every measure. Bach's approach to ornamentation can also be seen in a keyboard arrangement he made of Marcello's Oboe Concerto: he added explicit ornamentation, which centuries later is still played.[161]

Although Bach wrote no operas, he was not averse to the genre or its ornamented vocal style. In church music, Italian composers had imitated the operatic vocal style in genres such as the Neapolitan mass. In Protestant surroundings, there was more reluctance to adopt such a style for liturgical music. Kuhnau had notoriously shunned opera and Italian virtuoso vocal music.[162] Bach was less moved. After a performance of his St Matthew Passion it was described as sounding like opera.[163]

Continuo instrument solos

[edit]In concerted playing in Bach's time, the basso continuo, consisting of instruments such as viola da gamba or cello, and harpsichord or organ, usually had the role of accompaniment, providing a piece's harmonic and rhythmic foundation. Beginning in the 1720s Bach had the organ play concertante (i.e., as a soloist) with the orchestra in instrumental cantata movements,[164] a decade before Handel published his first organ concertos.[165] Apart from the fifth Brandenburg Concerto and the Triple Concerto, which already had harpsichord soloists in the 1720s, Bach wrote and arranged his harpsichord concertos in the 1730s,[166] and in his sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord neither instrument plays a continuo part: they are treated as equal soloists, far beyond the figured bass. In this way, Bach played a key role in the development of genres such as the keyboard concerto.[140]

Instrumentation

[edit]Bach wrote virtuoso music for specific instruments as well as music independent of instrumentation. For instance, the sonatas and partitas for solo violin are considered among the finest works written for violin, within reach of only accomplished players. The music fits the instrument, using the full gamut of its possibilities and requiring virtuosity but without bravura.[141] Notwithstanding that the music and the instrument seem inseparable, Bach transcribed some pieces in this collection for other instruments. For example, Bach transcribed one of the cello suites for lute.[167] In this sense, it is no surprise that Bach's music is easily and often performed on instruments it was not written for, that it is transcribed so often, and that his melodies turn up in unexpected places, such as jazz music. Apart from this, Bach left several compositions without specified instrumentation: the canons BWV 1072–1078 are in that category, as is the bulk of the Musical Offering and the Art of Fugue.[168]

Counterpoint

[edit]Another characteristic of Bach's style is his extensive use of counterpoint, as opposed to the homophony used in his four-part chorale settings, for example. Bach's canons, and especially his fugues, are the most characteristic of this style, which he did not invent but contributed to so fundamentally as to influence many followers.[169] Fugues are as characteristic of Bach's style as, for instance, sonata form is of the composers of the Classical period.[142]

These strictly contrapuntal compositions, and most of Bach's music in general, are characterised by distinct melodic lines for each voice, where the chords formed by the notes sounding at a given point follow the rules of four-part harmony. Forkel, Bach's first biographer, gives this description of this feature of Bach's music, which sets it apart from most other music:

If the language of music is merely the utterance of a melodic line, a simple sequence of musical notes, it can justly be accused of poverty. The addition of a Bass puts it upon a harmonic foundation and clarifies it but defines rather than gives it added richness. A melody so accompanied—even though all the notes are not those of the true Bass—or treated with simple embellishments in the upper parts or with simple chords used to be called "homophony". But it is a very different thing when two melodies are so interwoven that they converse together like two persons upon a footing of pleasant equality/... From 1720, when he was thirty-five until he died in 1750, Bach's harmony consists in this melodic interweaving of independent melodies, so perfect in their union that each part seems to constitute the true melody... Even in his four-part writing, we can, not infrequently, leave out the upper and lower parts and still find the middle parts harmonious and agreeable.[170]

Structure and lyrics

[edit]Bach devoted more attention than his contemporaries to the structure of his compositions. This can be seen in minor adjustments he made when adapting someone else's work, such as his earliest version of the "Keiser" St Mark Passion, where he enhances scene transitions,[171] and in the architecture of his own work, such as his Magnificat[158] and Leipzig Passions. In his last years, Bach revised several of his compositions, sometimes by recasting them in an enhanced structure for emphasis, as with, for example, the Mass in B minor. Bach's known preoccupation with structure led to various numerological analyses of his compositions. These peaked around the 1970s. Many were later rejected, especially those that wandered into symbolism-ridden hermeneutics.[172][173]

The librettos, or lyrics, of his vocal compositions played an essential role for Bach. He sought collaboration with various text authors for his cantatas and major vocal compositions, possibly writing or adapting such texts himself to make them fit the structure of the composition when he could not rely on the talents of other text authors. His collaboration with Picander for the St Matthew Passion libretto is best known, but there was a similar process in achieving a multi-layered structure for his St John Passion libretto a few years earlier.[174][175]

Fugue structure

[edit]Among the compositional techniques Bach used, the form of the fugue recurs throughout his lifetime; a fugue (derives from the Latin with the meaning "flight" or "escape"[176]) is a contrapuntal, polyphonic compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches), which recurs frequently throughout the composition. Most fugues open with the subject,[177] which then sounds successively in each voice. When each voice has completed its entry of the subject, the exposition is complete. This is often followed by a connecting passage, or episode, developed from previously heard material; further "entries" of the subject are then heard in related keys. Episodes (if applicable) and entries are usually alternated until the final entry of the subject, at which point the music has returned to the opening key, or tonic, which is often followed by a coda.[178][179][180] Bach was well known for his fugues and shaped his own works after those of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Johann Jakob Froberger, Johann Pachelbel, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Dieterich Buxtehude and others.[181]

Copies, arrangements, and uncertain attributions

[edit]In his early youth, Bach copied pieces by other composers to learn from them.[182] Later, he copied and arranged music for performance or as study material for his pupils. Some of these pieces, like "Bist du bei mir" (copied not by Bach but by Anna Magdalena), became famous before being associated with Bach. Bach copied and arranged Italian masters such as Vivaldi (e.g. BWV 1065), Pergolesi (BWV 1083) and Palestrina (Missa Sine nomine), French masters such as François Couperin (BWV Anh. 183), and various German masters, including Telemann (e.g. BWV 824=TWV 32:14) and Handel (arias from Brockes Passion), and music by members of his own family. He also often copied and arranged his own music (e.g. movements from cantatas for his short masses BWV 233–236), as his music was likewise copied and arranged by others. Some of these arrangements, like the late 19th-century "Air on the G String", helped to popularise Bach's music.[183][184][185]

The question of "who copied whom" is sometimes unclear. For instance, Forkel mentions a Mass for double chorus among Bach's works. It was published and performed in the early 19th century. Although a score partially in Bach's handwriting exists, the work was later considered spurious.[186] In 1950, the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis was designed to keep such works out of the main catalogue; if there was a strong association with Bach, they could be listed in its appendix (German: Anhang, abbreviated as Anh.). Thus, for instance, the Mass for double chorus became BWV Anh. 167. But this was far from the end of the attribution problems. For instance, Schlage doch, gewünschte Stunde, BWV 53, was later attributed to Melchior Hoffmann. For other works, Bach's authorship was put in doubt: the best-known organ composition in the BWV catalogue, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565, was one of these uncertain works in the late 20th century.[187]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

In the 18th century Bach's music was appreciated mostly by distinguished connoisseurs. The 19th century started with the publication of the first biography of Bach and ended with the Bach Gesellschaft's completion and publication of all his known works. Starting with the Bach Revival, he began to be regarded as one of the greatest composers, a reputation he has maintained. The BACH motif, which Bach occasionally used in his compositions, has been used in dozens of tributes to him since the 19th century.[188]

18th century

[edit]

In his own time, Bach was highly regarded by his colleagues,[189] but his reputation outside this small circle of connoisseurs was due not to his compositions (which had an extremely narrow circulation),[16] but to his virtuosic abilities. Nevertheless, during his life, Bach received public recognition, such as the title of court composer by Augustus III of Poland and the appreciation he was shown by Frederick the Great and Hermann Karl von Keyserling. This appreciation contrasted with the humiliations he faced, for instance, in Leipzig.[190] Bach also had detractors in the contemporary press (Johann Adolf Scheibe suggested he write less complex music) and supporters, such as Johann Mattheson and Lorenz Christoph Mizler.[191][192][193] After his death, Bach's reputation as a composer initially declined: his work was regarded as old-fashioned compared to the emerging galant style.[194] He was remembered more as a virtuoso organ player and a teacher. The bulk of the music printed during his lifetime was for organ or harpsichord.[46]

Bach's surviving family members, who inherited many of his manuscripts, were not all equally concerned with preserving them, leading to considerable losses.[195] Carl Philipp Emanuel, his second-eldest son, was most active in safeguarding his father's legacy: he co-authored his father's obituary, contributed to the publication of his four-part chorales,[196] presented some of his works, and helped preserve the bulk of his previously unpublished work.[197][198] Later, just after the turn of the century in 1805, Abraham Mendelssohn, who had married one of Itzig's granddaughters, bought a substantial collection of Bach manuscripts that had come down from C. P. E. Bach, and donated it to the Berlin Sing-Akademie.[199]

Wilhelm Friedemann, the eldest son, performed several of his father's cantatas in Halle but, after becoming unemployed, sold part of his large collection of his father's works.[200][201][202] Several students of Bach, such as his son-in-law Johann Christoph Altnickol, Johann Friedrich Agricola, Johann Kirnberger, and Johann Ludwig Krebs, contributed to the dissemination of his legacy. The early devotees were not all musicians; for example, in Berlin, Daniel Itzig, a high official of Frederick the Great's court, venerated Bach.[203] His eldest daughters took lessons from Kirnberger and their sister Sara from Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, who was in Berlin from 1774 to 1784.[203][204] Sara Itzig Levy became an avid collector of work by J. S. Bach and his sons and was a patron of C. P. E. Bach.[204]

While Bach was in Leipzig, performances of his church music were limited to some of his motets and, under his student cantor Johann Friedrich Doles, some of his Passions.[205] A new generation of Bach aficionados emerged who studiously collected and copied his music, including some of his large-scale works, such as the Mass in B minor, and performed it privately. One was Gottfried van Swieten, a high-ranking Austrian official who was instrumental in passing Bach's legacy on to the composers of the Viennese school. Haydn owned manuscript copies of The Well-Tempered Clavier and the Mass in B minor and was influenced by Bach's music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart owned a copy of one of Bach's motets,[206] transcribed some of his instrumental works (Preludes and Fugues for Violin, Viola and Cello, K. 404a (1782), Fugues for 2 Violins, Viola and Cello, K. 405 (1782)),[207][208] and wrote contrapuntal music influenced by his style.[209][210] Ludwig van Beethoven had learned The Well-Tempered Clavier in its entirety by the time he was 11 in 1781 and called Bach the Urvater der Harmonie (progenitor of harmony).[5][211][212][213][214]

19th century

[edit]

In 1802 Johann Nikolaus Forkel published Johann Sebastian Bach: His Life, Art, and Work, the first Bach biography, dedicated to van Swieten.[215] In 1805, Abraham Mendelssohn bought a substantial collection of Bach manuscripts that had come down from C. P. E. Bach, and donated it to the Berlin Sing-Akademie.[203] The Sing-Akademie occasionally performed Bach's works in public concerts, for instance, his first keyboard concerto, with Sara Itzig Levy at the piano.[203] Since the 19th-century Bach Revival, he has been widely regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music.[216]

The first decades of the 19th century saw an increasing number of first publications of Bach's music: Breitkopf & Härtel started publishing chorale preludes,[217] Hoffmeister harpsichord music,[218] and The Well-Tempered Clavier was printed concurrently by N. Simrock (Germany), Hans Georg Nägeli (Switzerland) and Franz Anton Hoffmeister (Germany and Austria) in 1801.[219] Vocal music was also published: motets in 1802 and 1803, followed by the E♭ major version of the Magnificat, the Kyrie-Gloria Mass in A major, and the cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (BWV 80).[220] In 1818 the publisher Hans Georg Nägeli called the Mass in B minor the greatest composition ever.[5] Bach's influence was felt in the next generation of early Romantic composers.[211] Abraham's son Felix, aged 13, produced his first Magnificat setting in 1822, and it is clearly inspired by the then-unpublished D major version of Bach's Magnificat.[221]

Felix Mendelssohn's 1829 performance of the St Matthew Passion precipitated the Bach Revival.[222] The St John Passion saw its 19th-century premiere in 1833, and the first public performance of the Mass in B minor followed in 1844. Besides these and other public performances and increased coverage of the composer and his compositions in printed media, the 1830s and 1840s also saw the first publication of more Bach vocal works: six cantatas, the St Matthew Passion, and the Mass in B minor. A series of organ compositions were first published in 1833.[223] Frédéric Chopin started composing his 24 Preludes, Op. 28, inspired by The Well-Tempered Clavier,[224] in 1835, and Robert Schumann published his Sechs Fugen über den Namen BACH in 1845. Bach's music was transcribed and arranged to suit contemporary tastes and performance practice by composers such as Carl Friedrich Zelter, Robert Franz, and Franz Liszt, or combined with new music such as the melody line of Charles Gounod's "Ave Maria".[5][225]

In 1850 the Bach-Gesellschaft (Bach Society) was founded to promote Bach's music. The Society chose Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 1 as the first composition in the first volume of the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (BGA). Robert Schumann, the publisher of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Thomaskantor Moritz Hauptmann, and the philologist Otto Jahn initiated this first complete edition of Bach's works a century after his death.[226][227] Its first volume was published in 1851, edited by Hauptmann.[228] In the second half of the 19th century, the Society published a comprehensive edition of his works. In 1854, Bach was deemed one of the Three Bs by Peter Cornelius, the others being Beethoven and Hector Berlioz. (Hans von Bülow later replaced Berlioz with Brahms.) From 1873 to 1880 Philipp Spitta published Johann Sebastian Bach, the standard work on Bach's life and music.[229] During the 19th century, 200 books were published on Bach. By the end of the century, local Bach societies were established in several cities, and his music had been performed in all major musical centres.[5] In 19th-century Germany, Bach was coupled with nationalist feeling. In England, Bach was coupled with a revival of religious and Baroque music. By the end of the century, Bach was firmly established as one of the greatest composers, recognised for both his instrumental and his vocal music.[5]

20th century

[edit]During the 20th century, recognition of the musical and pedagogic value of Bach's works continued, as in the promotion of the cello suites by Pablo Casals, the first major performer to record them.[230] Claude Debussy called Bach a "benevolent God" "to whom musicians should offer a prayer before setting to work so that they may be preserved from mediocrity."[231] Glenn Gould's debut 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations transformed the work from an obscure piece often considered "esoteric" to part of the standard piano repertoire.[232] The album had "astonishing" sales for a classical work: it was reported to have sold 40,000 copies by 1960, and had sold more than 100,000 by the time of Gould's death in 1982.[233][234] Andres Segovia left behind a large body of edited works and transcriptions for classical guitar, notably a transcription of the Chaconne from the 2nd Partita for Violin (BWV 1004).[235]

A significant development in the later 20th century was historically informed performance practice, with forerunners such as Nikolaus Harnoncourt acquiring prominence through their performances of Bach's music.[236] Bach's keyboard music was again performed on the harpsichord and other Baroque instruments rather than on modern pianos and 19th-century romantic organs. Ensembles playing and singing Bach's music not only kept to the instruments and the performance style of his day but were also reduced to the size of the groups Bach used for his performances.[237] But that was not the only way Bach's music came to the forefront in the 20th century: his music was heard in versions ranging from Ferruccio Busoni's late-romantic Bach-Busoni Editions for piano to the orchestrations of Leopold Stokowski, whose interpretation of the Toccata and Fugue in D minor opened Disney's Fantasia film.[238]

Bach's music has influenced other genres. Jazz musicians have adapted it, with Jacques Loussier,[239] Ian Anderson, Uri Caine, and the Modern Jazz Quartet among those creating jazz versions of his works.[240] Several 20th-century composers referred to Bach or his music, for example Eugène Ysaÿe in Six Sonatas for solo violin,[241] Dmitri Shostakovich in 24 Preludes and Fugues,[242] and Heitor Villa-Lobos in Bachianas Brasileiras (tr. Bach-inspired Brazilian pieces). A wide variety of publications involved Bach: there were the Bach Jahrbuch publications of the Neue Bachgesellschaft and various other biographies and studies by, among others, Albert Schweitzer, Charles Sanford Terry, Alfred Dürr, Christoph Wolff, Peter Williams, and John Butt,[n 3] and the 1950 first edition of the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis. Books such as Gödel, Escher, Bach put the composer's art in a wider perspective. Bach's music was extensively listened to, performed, broadcast, arranged, adapted, and commented upon in the 1990s.[243] Around 2000, the 250th anniversary of Bach's death, three record companies issued box sets of recordings of his complete works.[244][245][246]

Three works by Bach are featured on the Voyager Golden Record, a gramophone record containing a broad sample of the images, sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into space with the two Voyager probes: the first movement of Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 (conducted by Karl Richter), the "Gavotte en rondeaux" from the Partita for Violin No. 3 (played by Arthur Grumiaux), and the Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C major from The Well-Tempered Clavier (played by Glenn Gould).[247] Twentieth-century tributes to Bach include statues erected in his honour and things such as streets and space objects named after him.[248][249] A multitude of musical ensembles, such as the Bach Aria Group, Deutsche Bachsolisten, Bachchor Stuttgart, and Bach Collegium Japan took the composer's name. Bach festivals were held on several continents, and competitions and prizes such as the International Johann Sebastian Bach Competition and the Royal Academy of Music Bach Prize were named after him. While by the end of the 19th century, Bach had been inscribed in nationalism and religious revival, the late 20th century saw Bach as the subject of a secularised art-as-religion (Kunstreligion).[5][243]

-

1908 Statue of Bach in front of the Thomaskirche in Leipzig

-

28 July 1950: memorial service for Bach in Leipzig's Thomaskirche, on the 200th anniversary of the composer's death

21st century

[edit]In the 21st century Bach's compositions have become available online, for instance at the International Music Score Library Project.[250] High-resolution facsimiles of Bach's autographs became available at the Bach Digital website.[251] 21st-century biographers include Christoph Wolff, Peter Williams, and John Eliot Gardiner.[n 4] In 2011 Anthony Tommasini, chief classical music critic of The New York Times, ranked Bach the greatest composer of all time, "for his matchless combination of masterly musical engineering (as one reader put it) and profound expressivity. Since writing about Bach in the first article of this series I have been thinking more about the perception that he was considered old-fashioned in his day. Haydn was 18 when Bach died, in 1750, and Classicism was stirring. Bach was surely aware of the new trends. Yet he reacted by digging deeper into his way of doing things. In his austerely beautiful Art of Fugue, left incomplete at his death, Bach reduced complex counterpoint to its bare essentials, not even indicating the instrument (or instruments) for which these works were composed... through his chorales alone Bach explored the far reaches of tonal harmony."[252]

Alex Ross wrote, "Bach became an absolute master of his art by never ceasing to be a student of it. His most exalted sacred works—the two extant Passions, from the seventeen-twenties, and the Mass in B Minor, completed not long before his death in 1750—are feats of synthesis, mobilizing secular devices to spiritual ends. They are rooted in archaic chants, hymns, and chorales. They honour, with consummate skill, the scholastic discipline of canon and fugue... Their furious development of brief motifs anticipates Beethoven, who worshipped Bach when he was young. And their most daring harmonic adventures—for example, the otherworldly modulations in the 'Confiteor' of the B-Minor Mass—look ahead to Wagner, even to Schoenberg."[253] The liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church has a feast day for Bach on 28 July;[254] on the same day, the Calendar of Saints of some Lutheran churches, such as the ELCA, remembers Bach, Handel, and Heinrich Schütz.[255] As of 2013 over 150 recordings have been made of The Well-Tempered Clavier.[256] In 2015 Bach's handwritten personal copy of the Mass in B minor, held by the Berlin State Library, was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[257] On March 21, 2019, Bach was celebrated in an interactive Google Doodle that used machine learning to synthesize a tune in his signature style.[258]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ German pronunciation: [ˈjoːhan zeˈbasti̯a(ː)n ˈbax] ⓘ. The surname is pronounced /bɑːx/ BAHKH[2][3] or /bɑːk/ BAHK[4] in English.

- ^ Bach's birthdate—21 March 1685—is according to the Julian calendar (Old Style; O.S.), used in German regions at the time of his birth. From 18 February 1700 onwards, Protestant Germany introduced the Gregorian calendar, under which Bach's birthdate would be 31 March 1685 (New Style; N.S.).[9]

- ^ See Schweitzer 1911 (1905 and 1908 editions; Terry 1928; Dürr 1981; Dürr & Jones 2006 (English translation); Wolff 1991; Wolff 2000; Williams 1980; Butt 1997

- ^ See Wolff 2000; Williams 2003a; Williams 2007; Williams 2016; Gardiner 2013

Citations

[edit]- ^ Wolff & Emery 2001, "10. Iconography".

- ^ "Bach, Johann Sebastian". Lexico. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Bach". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Bach". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 30 April 2025. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g McKay, Cory. "The Bach Reception in the 18th and 19th century"

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Geck 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 525.

- ^ a b Boyd 1999, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 5.

- ^ Williams 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Boyd 1999, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Wolff et al. 2018, II. List of all family members alphabetically by first name.

- ^ a b Boyd 1999, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Wolff & Emery 2001.

- ^ a b Miles 1962, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Boyd 1999, pp. 7–8.

- ^ David, Mendel & Wolff 1998, p. 299.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 19, 46.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 170.

- ^ Spitta 1899a, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b Eidam 2001, Ch. I

- ^ a b c d e f g "Johann Sebastian Bach: A Detailed Informative Biography". The Baroque Music Site. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Researchers Find Bach's Oldest Manuscripts" (Press release). 2006.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Forkel 1920, Table VII, p. 309.

- ^ Spitta 1899b, p. 11.

- ^ Geiringer 1966, p. 50.

- ^ Wolff 1983, pp. 98, 111.

- ^ Rich 1995, p. 27.

- ^ Boyd 1999, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Chiapusso 1968, p. 62.

- ^ Williams 2003a, p. 40.

- ^ Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc., 2000), 96.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 83ff

- ^ Snyder, Kerala J. (2007). Dieterich Buxtehude: Organist in Lübeck (2nd ed.). University Rochester Press. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-1-58046-253-2. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015.

- ^ Sojourn: Jan Adams Reincken Archived 22 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, by Timothy A. Smith

- ^ a b Wolff 2000, pp. 102–104

- ^ Williams 2003a, p. 38–39.

- ^ Bach Digital Work 00005 at www

.bach-digital .de - ^ Isoyama, Tadashi (1995). "Cantata No. 71: Gott ist mein König (BWV 71)" (PDF). Bach-Cantatas. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ a b Emans & Hiemke 2015, pp. 227–234.

- ^ "History of the Bach House". Bach House Weimar. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Thornburgh, Elaine. "Baroque Music – Part One". Music in Our World. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ Chiapusso 1968, p. 168.

- ^ Schweitzer 1923, p. 331.

- ^ Koster, Jan. "Weimar (II) 1708–1717". J. S. Bach Archive and Bibliography. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ a b Sadie, Julie Anne, ed. (1998). Companion to Baroque Music. University of California Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-520-21414-9. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015.

- ^ Wolff 2000, pp. 147, 156.

- ^ a b Wolff 1991, p. 30

- ^ Gardiner, John Eliot (2010). "Cantatas for Christmas Day: Herderkirche, Weimar" (PDF). pp. 1–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Wolff, Christoph (1996). "From Konzertmeister to Thomaskantor: Bach's Cantata Production 1713–1723" (PDF). pp. 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ David, Mendel & Wolff 1998, p. 80.

- ^ Miles 1962, p. 57.

- ^ Boyd 1999, p. 74.

- ^ Dellal 2018.

- ^ Van Til 2007, pp. 69, 372.

- ^ Dent 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Spaeth 1937, p. 37.

- ^ a b Wolff 2013, p. 253

- ^ Spitta 1899b, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Wolff 2013, p. 345.

- ^ Spitta 1899b, p. 265.

- ^ Spitta 1899b, p. 184.

- ^ "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)". British Library: Online Gallery. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ Wolff 2013, p. 348.

- ^ Wolff 2013, p. 349.

- ^ Alfred Dörffel. Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe Volume 27: Thematisches Verzeichniss der Kirchencantaten No. 1–120. Breitkopf & Härtel, 1878. Introduction, p. VI

- ^ Dürr & Jones 2006, p. 384.

- ^ Wolff 1997, p. 5

- ^ Wolff 2002.

- ^ "Motets BWV 225–231". Bach Cantatas Website. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "Works of Other Composers Performed by J.S. Bach". Bach Cantatas Website. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Boyd 1999, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Spitta 1899b, pp. 288–290.

- ^ Spitta 1899b, pp. 281, 287.

- ^ Alfred Dörffel. Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe Volume 27: Thematisches Verzeichniss der Kirchencantaten No. 1–120. Breitkopf & Härtel, 1878. Introduction, pp. V–IX

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 341.

- ^ Stauffer 2008

- ^ Robin A. Leaver, "St Matthew Passion" Oxford Composer Companions: J. S. Bach, ed. Malcolm Boyd. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1999): 430. "Until 1975 it was thought that the St Matthew Passion was originally composed for Good Friday 1729, but modern research strongly suggests that it was performed two years earlier."

- ^ Work 01680 at Bach Digital website, 17 October 2015

- ^ a b "Bach Mass in B Minor BWV 232". The Baroque Music Site. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Bach Digital Work 00079

- ^ US-PRu M 3.1. B2 C5. 1739q Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ GB-Lbl Add. MS. 35021 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ Glöckner 2001

- ^ D-B Mus. ms. 16714 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-Cv A.V,1109,(1), 1a Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine and 1b Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 195 Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B Mus. ms. 1160 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-WFe 191 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website (RISM 250000899)

- ^ D-Bsa SA 301, Fascicle 1 Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine and Fascicle 2 Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ Neuaufgefundenes Bach-Autograph in Weißenfels Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at lisa

.gerda-henkel-stiftung .de - ^ F-Pn Ms. 17669 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B N. Mus. ms. 468 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine and Privatbesitz C. Thiele, BWV deest (NBA Serie II:5) Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B N. Mus. ms. 307 Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 271, Fascicle 2 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B Mus. ms. 30199, Fascicle 14 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine and D-B Mus. ms. 17155/16 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ D-B Mus. ms. 7918 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- ^ Musikalische Bibliothek, III.2 [1746], 353 Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Felbick 2012, 284. In 1746, Mizler announced the membership of three famous members, Musikalische Bibliothek, III.2 [1746], 357 Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Musikalische Bibliothek, IV.1 [1754], 108 and Tab. IV, fig. 16 (Source online); letter of Mizler to Spieß, 29 June 1748, in: Hans Rudolf Jung and Hans-Eberhard Dentler: Briefe von Lorenz Mizler und Zeitgenossen an Meinrad Spieß, in: Studi musicali 2003, Nr. 32, 115.

- ^ David, Mendel & Wolff 1998, p. 224.

- ^ US-PRscheide BWV 645–650 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine (original print of the Schübler Chorales with Bach's handwritten corrections and additions from before August 1748 – description at Bach Digital website)

- ^ Breig, Werner (2010). "Introduction Archived 22 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine" (pp. 14, 17–18) in Vol. 6: Clavierübung III, Schübler-Chorales, Canonische Veränderungen Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine of Johann Sebastian Bach: Complete Organ Works. Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Breitkopf.

- ^ a b Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel; Agricola, Johann Friedrich (1754). "Nekrolog". Musikalische Bibliothek (in German). IV.1. Mizlerischer Bücherverlag: 158–173. Printed in translation in David, Mendel & Wolff 1998, p. 299.

- ^ Hans Gunter Hoke: "Neue Studien zur Kunst der Fuge BWV 1080", in: Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 17 (1975), 95–115; Hans-Eberhard Dentler: "Johann Sebastian Bachs Kunst der Fuge – Ein pythagoreisches Werk und seine Verwirklichung", Mainz 2004; Hans-Eberhard Dentler: "Johann Sebastian Bachs Musicalisches Opfer – Musik als Abbild der Sphärenharmonie", Mainz 2008.

- ^ Chiapusso 1968, p. 277.

- ^ Rathey, Markus (15 July 2014). Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B Minor: The Greatest Artwork of All Times and All People (PDF). The Tangeman Lecture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2014.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 442, from David, Mendel & Wolff 1998

- ^ Zegers, Richard H.C. (2005). "The Eyes of Johann Sebastian Bach". Archives of Ophthalmology. 123 (10): 1427–1430. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.10.1427. ISSN 0003-9950. PMID 16219736.

- ^ Hanford, Jan. "J.S. Bach: Timeline of His Life". J.S. Bach Home Page. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "Johann Sebastian Bach – Eine Chronologie | Bach-Archiv Leipzig" [Johann Sebastian Bach – A Chronology | Bach Archive Leipzig]. www.bach-leipzig.de. Retrieved 16 September 2025.

- ^ David, Mendel & Wolff 1998, p. 188.

- ^ Spitta 1899c, p. 274.

- ^ Zegers, Richard H.C.; Maas, Mario; Koopman, A.G. & Maat, George J.R. (2009). "Are the Alleged Remains of Johann Sebastian Bach Authentic?" (PDF). The Medical Journal of Australia. 190 (4): 213–216. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02354.x. PMID 19220191. S2CID 7925258. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2013.

- ^ David, Mendel & Wolff 1998, pp. 191–197.

- ^ "Did Bach Really Leave Art of Fugue Unfinished?". The Art of Fugue. American Public Media. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Wolff 2000, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e Butler 2011

- ^ a b c Talbot 2011, pp. 28–29 and p. 54

- ^ "Concerto II: del Sig. Alexandro Marcello" in Concerti a Cinque: Con Violini, Oboè, Violetta, Violoncello e Basso Continuo, Del Signori G. Valentini, A. Vivaldi, T. Albinoni, F. M. Veracini, G. Saint Martin, A. Marcello, G. Rampin, A. Predieri. – Volume I. Amsterdam: Jeanne Roger (Catalogue No. 432), [1717]

- ^ D935 and Z799 in Selfridge-Field 1990

- ^ Jones 2007, pp. 143–144

- ^ Schulenberg 2013, pp. 132-133 and footnote 38, pp. 462–463

- ^ Schulenberg 2016.

- ^ Schulenberg 2013, pp. 117-1339fn

- ^ Talbot & Lockey 2020.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Corelli, Arcangelo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 143.

- ^ Waterman, George Gow, and James R. Anthony. 2001. "French Overture". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ Lockspeiser, E. “French Influences on Bach.” Music & Letters, vol. 16, no. 4, 1935, pp. 312–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/728728. Accessed 6 June 2025.

- ^ The Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago. 1990. p. 445, Volume 10.

- ^ The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 1. Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. 11 January 2013. p. 230. ISBN 9780415994033.

- ^ a b Spitta 1899c, vol. 3, appendix XII, p. 315.

- ^ a b Eidam 2001, Ch. IV.

- ^ a b Donington 1982, p. 91.

- ^ a b Schulenberg 2006, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Lester 1999, pp. 3–24

- ^ a b Eidam 2001, Ch. XXX.

- ^ Don O. Franklin. "The Libretto of Bach's John Passion and the Doctrine of Reconciliation: An Historical Perspective", pp. 179–203 Archived 31 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Vol. 143 edited by A. A. Clement, 1995.

- ^ Blanning, T. C. W. (2008). The Triumph of Music: The Rise of Composers, Musicians and Their Art. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-674-03104-3.

And of course the greatest master of harmony and counterpoint of all time was Johann Sebastian Bach, 'the Homer of music'.

- ^ Emans & Hiemke 2015, p. 227.

- ^ "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)". British Library. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Herl 2004, p. 123.

- ^ Fuller Maitland, J. A., ed. (1911). "Johann Sebastian Bach". Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 1. Macmillan Publishers. p. 154.

- ^ Leaver 2007, pp. 280, 289–291.

- ^ E, Matt (14 January 2019). "A Beginner's Guide to 4-Part Harmony: Notation, Ranges, Rules & Tips". School of Composition. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ Marshall and Leaver 2001.

- ^ Huizenga, Tom. "A Visitor's Guide to the St. Matthew Passion". NPR Music. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "The Well Tempered Clavier BWV 846–869". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Clemens Romijn. Liner notes for Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden, BWV 1083 (after Pergolesi's Stabat Mater). Brilliant Classics, 2000. (2014 reissue: J.S. Bach Complete Edition. "Liner notes" Archived 22 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine p. 54)

- ^ Jopi Harri. St. Petersburg Court Chant and the Tradition of Eastern Slavic Church Singing. Archived 20 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine Finland: University of Turku (2011), p. 24

- ^ Cristoph Rueger (ed.): "Johann Sebastian Bach" in Harenberg Klaviermusikführer. Harenberg, Dortmund 1984, ISBN 3-611-00679-3, pp. 85–86

- ^ Eidam 2001, Ch. IX.

- ^ a b Marshall, Robert L. (1989). Franklin, Don O. (ed.). On the Origin of Bach's Magnificat: A Lutheran Composer's Challenge. Vol. Bach Studies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-0-521-34105-9. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016.

- ^ Eidam 2001, Ch. III.

- ^ Klavierbüchlein für W. F. Bach Archived 18 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine at www

.bachdigital .de - ^ "Concerto in d Minor". Netherlands Bach Society.

- ^ Kuhnau, Johann (1700), Der musicalische Quack-Salber

- ^ Eidam 2001, Ch. XVIII.

- ^ André Isoir (organ) and Le Parlement de Musique conducted by Martin Gester. Johann Sebastian Bach: L'oeuvre pour orgue et orchestre. Calliope 1993. Liner notes by Gilles Cantagrel.

- ^ George Frideric Handel. 6 Organ Concertos, Op. 4 at IMSLP website

- ^ Peter Wollny, "Harpsichord Concertos," Archived 22 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine booklet notes for Andreas Staier's 2015 recording of the concertos, Harmonia mundi HMC 902181.82

- ^ BWV995 Archived 2009-09-04 at the Wayback Machine at JSBach.org. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ "Did Bach Intend Art of Fugue to Be Performed?". The Art of Fugue. American Public Media. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Walker, Paul (2001). "Fugue, §6: Late 18th century". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Forkel 1920, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Bach Digital Work 01677 at www

.bachdigital .de - ^ Williams 1980, p. 217