Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Barcode

View on Wikipedia

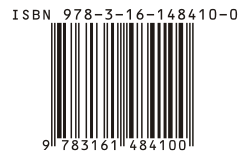

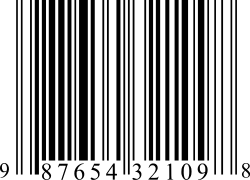

A barcode or bar code is a method of representing data in a visual, machine-readable form. Initially, barcodes represented data by varying the widths, spacings and sizes of parallel lines. These barcodes, now commonly referred to as linear or one-dimensional (1D), can be scanned by special optical scanners, called barcode readers, of which there are several types.

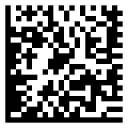

Later, two-dimensional (2D) variants were developed, using rectangles, dots, hexagons and other patterns, called matrix codes or 2D barcodes, although they do not use bars as such. Both can be read using purpose-built 2D optical scanners, which exist in a few different forms. Matrix codes can also be read by a digital camera connected to a microcomputer running software that takes a photographic image of the barcode and analyzes the image to deconstruct and decode the code. A mobile device with a built-in camera, such as a smartphone, can function as the latter type of barcode reader using specialized application software and is suitable for both 1D and 2D codes.

The barcode was invented by Norman Joseph Woodland and Bernard Silver and patented in the US in 1952.[1] The invention was based on Morse code[2] that was extended to thin and thick bars. However, it took over twenty years before this invention became commercially successful. UK magazine Modern Railways December 1962 pages 387–389 record how British Railways had already perfected a barcode-reading system capable of correctly reading rolling stock travelling at 100 mph (160 km/h) with no mistakes. An early use of one type of barcode in an industrial context was sponsored by the Association of American Railroads in the late 1960s. Developed by General Telephone and Electronics (GTE) and called KarTrak ACI (Automatic Car Identification), this scheme involved placing colored stripes in various combinations on steel plates which were affixed to the sides of railroad rolling stock. Two plates were used per car, one on each side, with the arrangement of the colored stripes encoding information such as ownership, type of equipment, and identification number.[3] The plates were read by a trackside scanner located, for instance, at the entrance to a classification yard, while the car was moving past.[4] The project was abandoned after about ten years because the system proved unreliable after long-term use.[3]

Barcodes became commercially successful when they were used to automate supermarket checkout systems, a task for which they have become almost universal. The Uniform Grocery Product Code Council had chosen, in 1973, the barcode design developed by George Laurer. Laurer's barcode, with vertical bars, printed better than the circular barcode developed by Woodland and Silver.[5] Their use has spread to many other tasks that are generically referred to as automatic identification and data capture (AIDC). The first successful system using barcodes was in the UK supermarket group Sainsbury's in 1972 using shelf-mounted barcodes which were developed by Plessey.[6][7] In June 1974, Marsh supermarket in Troy, Ohio used a scanner made by Photographic Sciences Corporation to scan the Universal Product Code (UPC) barcode on a pack of Wrigley's chewing gum.[8][5] QR codes, a specific type of 2D barcode, rose in popularity in the second decade of the 2000s due to the growth in smartphone ownership.[9]

Other systems have made inroads in the AIDC market, but the simplicity, universality and low cost of barcodes has limited the role of these other systems, particularly before technologies such as radio-frequency identification (RFID) became available after 2023.

History

[edit]This article duplicates the scope of other articles, specifically Universal Product Code#History. (December 2013) |

In 1948, Bernard Silver, a graduate student at Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US overheard the president of the local food chain, Food Fair, asking one of the deans to research a system to automatically read product information during checkout.[10] Silver told his friend Norman Joseph Woodland about the request, and they started working on a variety of systems. Their first working system used ultraviolet ink, but the ink faded too easily and was expensive.[11]

Convinced that the system was workable with further development, Woodland left Drexel, moved into his father's apartment in Florida, and continued working on the system. His next inspiration came from Morse code, and he formed his first barcode from sand on the beach. "I just extended the dots and dashes downwards and made narrow lines and wide lines out of them."[11] To read them, he adapted technology from optical soundtracks in movies, using a 500-watt incandescent light bulb shining through the paper onto an RCA935 photomultiplier tube (from a movie projector) on the far side. He later decided that the system would work better if it were printed as a circle instead of a line, allowing it to be scanned in any direction.

On 20 October 1949 Woodland and Silver filed a patent application for "Classifying Apparatus and Method", in which they described both the linear and bull's eye printing patterns, as well as the mechanical and electronic systems needed to read the code. The patent was issued on 7 October 1952 as US Patent 2,612,994.[1] In 1951, Woodland moved to IBM and continually tried to interest IBM in developing the system. The company eventually commissioned a report on the idea, which concluded that it was both feasible and interesting, but that processing the resulting information would require equipment that was some time off in the future.

IBM offered to buy the patent, but the offer was not accepted. Philco purchased the patent in 1962 and then sold it to RCA sometime later.[11]

Collins at Sylvania

[edit]During his time as an undergraduate, David Jarrett Collins worked at the Pennsylvania Railroad and became aware of the need to automatically identify railroad cars. Immediately after receiving his master's degree from MIT in 1959, he started work at GTE Sylvania and began addressing the problem. He developed a system called KarTrak using blue, white and red reflective stripes attached to the side of the cars, encoding a four-digit company identifier and a six-digit car number.[11] Light reflected off the colored stripes was read by photomultiplier vacuum tubes.[12]

The Boston and Maine Railroad tested the KarTrak system on their gravel cars in 1961. The tests continued until 1967, when the Association of American Railroads (AAR) selected it as a standard, automatic car identification, across the entire North American fleet. The installations began on 10 October 1967. However, the economic downturn and rash of bankruptcies in the industry in the early 1970s greatly slowed the rollout, and it was not until 1974 that 95% of the fleet was labeled. To add to its woes, the system was found to be easily fooled by dirt in certain applications, which greatly affected accuracy. The AAR abandoned the system in the late 1970s, and it was not until the mid-1980s that they introduced a similar system, this time based on radio tags.[13]

The railway project had failed, but a toll bridge in New Jersey requested a similar system so that it could quickly scan for cars that had purchased a monthly pass. Then the US Post Office requested a system to track trucks entering and leaving their facilities. These applications required special retroreflector labels. Finally, Kal Kan asked the Sylvania team for a simpler (and cheaper) version which they could put on cases of pet food for inventory control.

Computer Identics Corporation

[edit]In 1967, with the railway system maturing, Collins went to management looking for funding for a project to develop a black-and-white version of the code for other industries. They declined, saying that the railway project was large enough, and they saw no need to branch out so quickly.

Collins then quit Sylvania and formed the Computer Identics Corporation.[11] As its first innovations, Computer Identics moved from using incandescent light bulbs in its systems, replacing them with helium–neon lasers, and incorporated a mirror as well, making it capable of locating a barcode up to a meter (3 feet) in front of the scanner. This made the entire process much simpler and more reliable, and typically enabled these devices to deal with damaged labels, as well, by recognizing and reading the intact portions.

Computer Identics Corporation installed one of its first two scanning systems in the spring of 1969 at a General Motors (Buick) factory in Flint, Michigan.[11] The system was used to identify a dozen types of transmissions moving on an overhead conveyor from production to shipping. The other scanning system was installed at General Trading Company's distribution center in Carlstadt, New Jersey to direct shipments to the proper loading bay.

Universal Product Code

[edit]In 1966 the National Association of Food Chains (NAFC) held a meeting on the idea of automated checkout systems. RCA, which had purchased the rights to the original Woodland patent, attended the meeting and initiated an internal project to develop a system based on the bullseye code. The Kroger grocery chain volunteered to test it.

In the mid-1970s the NAFC established the Ad-Hoc Committee for U.S. Supermarkets on a Uniform Grocery-Product Code to set guidelines for barcode development. In addition, it created a symbol-selection subcommittee to help standardize the approach. In cooperation with consulting firm, McKinsey & Co., they developed a standardized 11-digit code for identifying products. The committee then sent out a contract tender to develop a barcode system to print and read the code. The request went to Singer, National Cash Register (NCR), Litton Industries, RCA, Pitney-Bowes, IBM and many others.[14] A wide variety of barcode approaches was studied, including linear codes, RCA's bullseye concentric circle code, starburst patterns and others.

In the spring of 1971 RCA demonstrated their bullseye code at another industry meeting. IBM executives at the meeting noticed the crowds at the RCA booth and immediately developed their own system. IBM marketing specialist Alec Jablonover remembered that the company still employed Woodland, and he established a new facility in Research Triangle Park to lead development.

In July 1972 RCA began an 18-month test in a Kroger store in Cincinnati. Barcodes were printed on small pieces of adhesive paper, and attached by hand by store employees when they were adding price tags. The code proved to have a serious problem; the printers would sometimes smear ink, rendering the code unreadable in most orientations. However, a linear code, like the one being developed by Woodland at IBM, was printed in the direction of the stripes, so extra ink would simply make the code "taller" while remaining readable. So on 3 April 1973 the IBM UPC was selected as the NAFC standard. IBM had designed five versions of UPC symbology for future industry requirements: UPC A, B, C, D, and E.[15]

NCR installed a testbed system at Marsh's Supermarket in Troy, Ohio, near the factory that was producing the equipment. On 26 June 1974, a 10-pack of Wrigley's Juicy Fruit gum was scanned, registering the first commercial use of the UPC.[16]

In 1971 an IBM team was assembled for an intensive planning session, threshing out, 12 to 18 hours a day, how the technology would be deployed and operate cohesively across the system, and scheduling a roll-out plan. By 1973, the team were meeting with grocery manufacturers to introduce the symbol that would need to be printed on the packaging or labels of all of their products. There were no cost savings for a grocery to use it, unless at least 70% of the grocery's products had the barcode printed on the product by the manufacturer. IBM projected that 75% would be needed in 1975.

Economic studies conducted for the grocery industry committee projected over $40 million in savings to the industry from scanning by the mid-1970s. Those numbers were not achieved in that time-frame and some predicted the demise of barcode scanning. The usefulness of the barcode required the adoption of expensive scanners by a critical mass of retailers while manufacturers simultaneously adopted barcode labels. Neither wanted to move first and results were not promising for the first couple of years, with Business Week proclaiming "The Supermarket Scanner That Failed" in a 1976 article.[16][17]

Sims Supermarkets were the first location in Australia to use barcodes, starting in 1979.[18]

Barcode system

[edit]A barcode system is a network of hardware and software, consisting primarily of mobile computers, printers, handheld scanners, infrastructure, and supporting software. Barcode systems are used to automate data collection where hand recording is neither timely nor cost effective. Despite often being provided by the same company, Barcoding systems are not radio-frequency identification (RFID) systems. Many companies use both technologies as part of larger resource management systems.

A typical barcode system consist of some infrastructure, either wired or wireless that connects some number of mobile computers, handheld scanners, and printers to one or many databases that store and analyze the data collected by the system. At some level there must be some software to manage the system. The software may be as simple as code that manages the connection between the hardware and the database or as complex as an ERP, MRP, or some other inventory management software.

Hardware

[edit]A wide range of hardware is manufactured for use in barcode systems by such manufacturers as Datalogic, Intermec, HHP (Hand Held Products), Microscan Systems, Unitech, Metrologic, PSC, and PANMOBIL, with the best known brand of handheld scanners and mobile computers being produced by Symbol,[citation needed] a division of Motorola.

Software

[edit]Some ERP, MRP, and other inventory management software have built in support for barcode reading. Alternatively, custom interfaces can be created using a language such as C++, C#, Java, Visual Basic.NET, and many others. In addition, software development kits are produced to aid the process.

Industrial adoption

[edit]In 1981 the United States Department of Defense adopted the use of Code 39 for marking all products sold to the United States military. This system, Logistics Applications of Automated Marking and Reading Symbols (LOGMARS), is still used by DoD and is widely viewed as the catalyst for widespread adoption of barcoding in industrial uses.[19]

Use

[edit]

Barcodes are widely used around the world in many contexts. In stores, UPC barcodes are pre-printed on most items other than fresh produce from a grocery store. This speeds up processing at check-outs and helps track items and also reduces instances of shoplifting involving price tag swapping, although shoplifters can now print their own barcodes.[20] Barcodes that encode a book's ISBN are also widely pre-printed on books, journals and other printed materials. In addition, retail chain membership cards use barcodes to identify customers, allowing for customized marketing and greater understanding of individual consumer shopping patterns. At the point of sale, shoppers can get product discounts or special marketing offers through the address or e-mail address provided at registration.

Barcodes are widely used in healthcare and hospital settings, ranging from patient identification (to access patient data, including medical history, drug allergies, etc.) to creating SOAP notes[21] with barcodes to medication management. They are also used to facilitate the separation and indexing of documents that have been imaged in batch scanning applications, track the organization of species in biology,[22] and integrate with in-motion checkweighers to identify the item being weighed in a conveyor line for data collection.

They can also be used to keep track of objects and people; they are used to keep track of rental cars, airline luggage, nuclear waste, express mail, and parcels. Barcoded tickets (which may be printed by the customer on their home printer, or stored on their mobile device) allow the holder to enter sports arenas, cinemas, theatres, fairgrounds, and transportation, and are used to record the arrival and departure of vehicles from rental facilities etc. This can allow proprietors to identify duplicate or fraudulent tickets more easily. Barcodes are widely used in shop floor control applications software where employees can scan work orders and track the time spent on a job.

Barcodes are also used in some kinds of non-contact 1D and 2D position sensors. A series of barcodes are used in some kinds of absolute 1D linear encoder. The barcodes are packed close enough together that the reader always has one or two barcodes in its field of view. As a kind of fiducial marker, the relative position of the barcode in the field of view of the reader gives incremental precise positioning, in some cases with sub-pixel resolution. The data decoded from the barcode gives the absolute coarse position. An "address carpet", used in digital paper, such as Howell's binary pattern and the Anoto dot pattern, is a 2D barcode designed so that a reader, even though only a tiny portion of the complete carpet is in the field of view of the reader, can find its absolute X, Y position and rotation in the carpet.[23][24]

Matrix codes can embed a hyperlink to a web page. A mobile device with a built-in camera might be used to read the pattern and browse the linked website, which can help a shopper find the best price for an item in the vicinity. Since 2005, airlines use an IATA-standard 2D barcode on boarding passes (Bar Coded Boarding Pass (BCBP)), and since 2008 2D barcodes sent to mobile phones enable electronic boarding passes.[25]

Some applications for barcodes have fallen out of use. In the 1970s and 1980s, software source code was occasionally encoded in a barcode and printed on paper (Cauzin Softstrip and Paperbyte[26] are barcode symbologies specifically designed for this application), and the 1991 Barcode Battler computer game system used any standard barcode to generate combat statistics.

Artists have used barcodes in art, such as Scott Blake's Barcode Jesus, as part of the post-modernism movement.

Symbologies

[edit]The mapping between messages and barcodes is called a symbology. The specification of a symbology includes the encoding of the message into bars and spaces, any required start and stop markers, the size of the quiet zone required to be before and after the barcode, and the computation of a checksum.

Linear symbologies can be classified mainly by two properties:

- Continuous vs. discrete

- Characters in discrete symbologies are composed of n bars and n − 1 spaces. There is an additional space between characters, but it does not convey information, and may have any width as long as it is not confused with the end of the code.

- Characters in continuous symbologies are composed of n bars and n spaces, and usually abut, with one character ending with a space and the next beginning with a bar, or vice versa. A special end pattern that has bars on both ends is required to end the code.

- Two-width vs. many-width

- A two-width, also called a binary bar code, contains bars and spaces of two widths, "wide" and "narrow". The precise width of the wide bars and spaces is not critical; typically, it is permitted to be anywhere between 2 and 3 times the width of the narrow equivalents.

- Some other symbologies use bars of two different heights (POSTNET), or the presence or absence of bars (CPC Binary Barcode). These are normally also considered binary bar codes.

- Bars and spaces in many-width symbologies are all multiples of a basic width called the module; most such codes use four widths of 1, 2, 3 and 4 modules.

Some symbologies use interleaving. The first character is encoded using black bars of varying width. The second character is then encoded by varying the width of the white spaces between these bars. Thus, characters are encoded in pairs over the same section of the barcode. Interleaved 2 of 5 is an example of this.

Stacked symbologies repeat a given linear symbology vertically.

The most common among the many 2D symbologies are matrix codes, which feature square or dot-shaped modules arranged on a grid pattern. 2D symbologies also come in circular and other patterns and may employ steganography, hiding modules within an image (for example, DataGlyphs).

Linear symbologies are optimized for laser scanners, which sweep a light beam across the barcode in a straight line, reading a slice of the barcode light-dark patterns. Scanning at an angle makes the modules appear wider, but does not change the width ratios. Stacked symbologies are also optimized for laser scanning, with the laser making multiple passes across the barcode.

In the 1990s development of charge-coupled device (CCD) imagers to read barcodes was pioneered by Welch Allyn. Imaging does not require moving parts, as a laser scanner does. In 2007, linear imaging had begun to supplant laser scanning as the preferred scan engine for its performance and durability.

2D symbologies cannot be read by a laser, as there is typically no sweep pattern that can encompass the entire symbol. They must be scanned by an image-based scanner employing a CCD or other digital camera sensor technology.

Barcode readers

[edit]

The earliest, and still[when?] the cheapest, barcode scanners are built from a fixed light and a single photosensor that is manually moved across the barcode. Barcode scanners can be classified into three categories based on their connection to the computer. The older type is the RS-232 barcode scanner. This type requires special programming for transferring the input data to the application program. Keyboard interface scanners connect to a computer using a PS/2 or AT keyboard–compatible adaptor cable (a "keyboard wedge"). The barcode's data is sent to the computer as if it had been typed on the keyboard.

Like the keyboard interface scanner, USB scanners do not need custom code for transferring input data to the application program. On PCs running Windows the human interface device emulates the data merging action of a hardware "keyboard wedge", and the scanner automatically behaves like an additional keyboard.

Most modern smartphones are able to decode barcode using their built-in camera. Google's mobile Android operating system can use their own Google Lens application to scan QR codes, or third-party apps like Barcode Scanner to read both one-dimensional barcodes and QR codes. Google's Pixel devices can natively read QR codes inside the default Pixel Camera app. Nokia's Symbian operating system featured a barcode scanner,[27] while mbarcode[28] is a QR code reader for the Maemo operating system. In Apple iOS 11, the native camera app can decode QR codes and can link to URLs, join wireless networks, or perform other operations depending on the QR Code contents.[29] Other paid and free apps are available with scanning capabilities for other symbologies or for earlier iOS versions.[30] With BlackBerry devices, the App World application can natively scan barcodes and load any recognized Web URLs on the device's Web browser. Windows Phone 7.5 is able to scan barcodes through the Bing search app. However, these devices are not designed specifically for the capturing of barcodes. As a result, they do not decode nearly as quickly or accurately as a dedicated barcode scanner or portable data terminal.[citation needed]

Quality control and verification

[edit]It is common for producers and users of bar codes to have a quality management system which includes verification and validation of bar codes.[31] Barcode verification examines scanability and the quality of the barcode in comparison to industry standards and specifications.[32] Barcode verifiers are primarily used by businesses that print and use barcodes. Any trading partner in the supply chain can test barcode quality. It is important to verify a barcode to ensure that any reader in the supply chain can successfully interpret a barcode with a low error rate. Retailers levy large penalties for non-compliant barcodes. These chargebacks can reduce a manufacturer's revenue by 2% to 10%.[33]

A barcode verifier works the way a reader does, but instead of simply decoding a barcode, a verifier performs a series of tests. For linear barcodes these tests are:

- Edge contrast (EC)[34]

- The difference between the space reflectance (Rs) and adjoining bar reflectance (Rb). EC=Rs-Rb

- Minimum bar reflectance (Rb)[34]

- The smallest reflectance value in a bar.

- Minimum space reflectance (Rs)[34]

- The smallest reflectance value in a space.

- Symbol contrast (SC)[34]

- Symbol contrast is the difference in reflectance values of the lightest space (including the quiet zone) and the darkest bar of the symbol. The greater the difference, the higher the grade. The parameter is graded as either A, B, C, D, or F. SC=Rmax-Rmin

- Minimum edge contrast (ECmin)[34]

- The difference between the space reflectance (Rs) and adjoining bar reflectance (Rb). EC=Rs-Rb

- Modulation (MOD)[34]

- The parameter is graded either A, B, C, D, or F. This grade is based on the relationship between minimum edge contrast (ECmin) and symbol contrast (SC). MOD=ECmin/SC The greater the difference between minimum edge contrast and symbol contrast, the lower the grade. Scanners and verifiers perceive the narrower bars and spaces to have less intensity than wider bars and spaces; the comparison of the lesser intensity of narrow elements to the wide elements is called modulation. This condition is affected by aperture size.

- Inter-character gap[34]

- In discrete barcodes, the space that disconnects the two contiguous characters. When present, inter-character gaps are considered spaces (elements) for purposes of edge determination and reflectance parameter grades.

- Defects

- Decode[34]

- Extracting the information which has been encoded in a bar code symbol.

- Decodability[34]

- Can be graded as A, B, C, D, or F. The Decodability grade indicates the amount of error in the width of the most deviant element in the symbol. The less deviation in the symbology, the higher the grade. Decodability is a measure of print accuracy using the symbology reference decode algorithm.

2D matrix symbols look at the parameters:

- Symbol contrast[34]

- Modulation[34]

- Decode[34]

- Unused error correction

- Fixed (finder) pattern damage

- Grid non-uniformity

- Axial non-uniformity[35]

Depending on the parameter, each ANSI test is graded from 0.0 to 4.0 (F to A), or given a pass or fail mark. Each grade is determined by analyzing the scan reflectance profile (SRP), an analog graph of a single scan line across the entire symbol. The lowest of the 8 grades is the scan grade, and the overall ISO symbol grade is the average of the individual scan grades. For most applications a 2.5 (C) is the minimal acceptable symbol grade.[36]

Compared with a reader, a verifier measures a barcode's optical characteristics to international and industry standards. The measurement must be repeatable and consistent. Doing so requires constant conditions such as distance, illumination angle, sensor angle and verifier aperture. Based on the verification results, the production process can be adjusted to print higher quality barcodes that will scan down the supply chain.

Bar code validation may include evaluations after use (and abuse) testing such as sunlight, abrasion, impact, moisture, etc.[37]

Barcode verifier standards

[edit]Barcode verifier standards are defined by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), in ISO/IEC 15426-1 (linear) or ISO/IEC 15426-2 (2D).[citation needed] The current international barcode quality specification is ISO/IEC 15416 (linear) and ISO/IEC 15415 (2D).[citation needed] The European Standard EN 1635 has been withdrawn and replaced by ISO/IEC 15416. The original U.S. barcode quality specification was ANSI X3.182. (UPCs used in the US – ANSI/UCC5).[citation needed] As of 2011 the ISO workgroup JTC1 SC31 was developing a Direct Part Marking (DPM) quality standard: ISO/IEC TR 29158.[38]

Benefits

[edit]In point-of-sale management, barcode systems can provide detailed up-to-date information on the business, accelerating decisions and with more confidence. For example:

- Fast-selling items can be identified quickly and automatically reordered.

- Slow-selling items can be identified, preventing inventory build-up.

- The effects of merchandising changes can be monitored, allowing fast-moving, more profitable items to occupy the best space.

- Historical data can be used to predict seasonal fluctuations very accurately.

- Items may be repriced on the shelf to reflect both sale prices and price increases.

- This technology also enables the profiling of individual consumers, typically through a voluntary registration of discount cards. While pitched as a benefit to the consumer, this practice is considered to be potentially dangerous by privacy advocates.[which?]

Besides sales and inventory tracking, barcodes are very useful in logistics and supply chain management.

- When a manufacturer packs a box for shipment, a unique identifying number (UID) can be assigned to the box.

- A database can link the UID to relevant information about the box; such as order number, items packed, quantity packed, destination, etc.

- The information can be transmitted through a communication system such as electronic data interchange (EDI) so the retailer has the information about a shipment before it arrives.

- Shipments that are sent to a distribution center (DC) are tracked before forwarding. When the shipment reaches its final destination, the UID gets scanned, so the store knows the shipment's source, contents, and cost.

Barcode scanners are relatively low cost and extremely accurate compared to key-entry, with only about 1 substitution error in 15,000 to 36 trillion characters entered.[39][unreliable source?] The exact error rate depends on the type of barcode.

Types of barcodes

[edit]Linear barcodes

[edit]A first generation, "one dimensional" barcode that is made up of lines and spaces of various widths or sizes that create specific patterns.

| Example | Symbology | Continuous or discrete | Bar type | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codabar | Discrete | Two | Old format used in libraries and blood banks and on airbills (out of date, but still widely used in libraries) | |

| Code 25 – Non-interleaved 2 of 5 | Continuous | Two | Industrial | |

| Code 25 – Interleaved 2 of 5 | Continuous | Two | Wholesale, libraries International standard ISO/IEC 16390 | |

|

Code 11 | Discrete | Two | Telephones (out of date) |

|

Farmacode or Code 32 | Discrete | Two | Italian pharmacode – use Code 39 (no international standard available) |

|

Code 39 | Discrete | Two | Various – international standard ISO/IEC 16388 |

|

Code 93 | Continuous | Many | Various |

|

Code 128 | Continuous | Many | Various – International Standard ISO/IEC 15417 |

| CPC Binary | Discrete | Two | ||

|

Data Logic 2 of 5 | Discrete | Two | Datalogic 2 of 5 can encode digits 0–9 and was used mostly in Chinese Postal Services. |

|

EAN 2 | Continuous | Many | Addon code (magazines), GS1-approved – not an own symbology – to be used only with an EAN/UPC according to ISO/IEC 15420 |

|

EAN 5 | Continuous | Many | Addon code (books), GS1-approved – not an own symbology – to be used only with an EAN/UPC according to ISO/IEC 15420 |

|

EAN-8, EAN-13 | Continuous | Many | Worldwide retail, GS1-approved – International Standard ISO/IEC 15420 |

| || | || | Facing Identification Mark | Discrete | Two | USPS business reply mail |

| GS1-128 (formerly named UCC/EAN-128), incorrectly referenced as EAN 128 and UCC 128 | Continuous | Many | Various, GS1-approved – just an application of the Code 128 (ISO/IEC 15417) using the ANS MH10.8.2 AI Datastructures. It is not a separate symbology. | |

|

GS1 DataBar, formerly Reduced Space Symbology (RSS) | Continuous | Many | Various, GS1-approved |

|

IATA 2 of 5 | Discrete | Two | IATA 2 of 5 version of Industrial 2 of 5 is used by International Air Transport Association had fixed 17 digits length with 16 valuable package identification digit and 17-th check digit. |

| Industrial 2 of 5 | Discrete | Two | Industrial 2 of 5 can encode only digits 0–9 and at this time has only historical value. | |

| ITF-14 | Continuous | Two | Non-retail packaging levels, GS1-approved – is just an Interleaved 2/5 Code (ISO/IEC 16390) with a few additional specifications, according to the GS1 General Specifications | |

|

ITF-6 | Continuous | Two | Interleaved 2 of 5 barcode to encode an addon to ITF-14 and ITF-16 barcodes. The code is used to encode additional data such as items quantity or container weight |

|

JAN | Continuous | Many | Used in Japan, similar to and compatible with EAN-13 (ISO/IEC 15420) |

|

Matrix 2 of 5 | Discrete | Two | Matrix 2 of 5 can encode digits 0–9 and was uses for warehouse sorting, photo finishing, and airline ticket marking. |

|

MSI | Continuous | Two | Used for warehouse shelves and inventory |

|

Pharmacode | Discrete | Two | Pharmaceutical packaging (no international standard available) |

| PLANET | Continuous | Tall/short | United States Postal Service (no international standard available) | |

| Plessey | Continuous | Two | Catalogs, store shelves, inventory (no international standard available) | |

| Telepen | Continuous | Two | Libraries (UK) | |

|

Universal Product Code (UPC-A and UPC-E) | Continuous | Many | Worldwide retail, GS1-approved – International Standard ISO/IEC 15420 |

2D barcodes

[edit]2D barcodes consist of bars, but use both dimensions for encoding.

| Example | Symbology | Continuous or discrete | Bar type | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia Post barcode | Discrete | 4 bar heights | An Australia Post 4-state barcode as used on a business reply paid envelope and applied by automated sorting machines to other mail when initially processed in fluorescent ink.[40] | |

|

Codablock | Continuous | Many | Codablock is a family of stacked 1D barcodes (in some cases counted as stacked 2D barcodes) which are used in health care industry (HIBC). |

|

Code 49 | Continuous | Many | Various |

|

Code 16K | The Code 16K (1988) is a multi-row bar code developed by Ted Williams at Laserlight Systems (USA) in 1992. In the US and France, the code is used in the electronics industry to identify chips and printed circuit boards. Medical applications in the USA are well known. Williams also developed Code 128, and the structure of 16K is based on Code 128. Not coincidentally, 128 squared happened to equal 16,384 or 16K for short. Code 16K resolved an inherent problem with Code 49. Code 49's structure requires a large amount of memory for encoding and decoding tables and algorithms. 16K is a stacked symbology.[41][42] | ||

|

DX film edge barcode | Neither | Tall/short | Color print film |

| Intelligent Mail barcode | Discrete | 4 bar heights | United States Postal Service, replaces both POSTNET and PLANET symbols (formerly named OneCode) | |

| Japan Post barcode | Discrete | 4 bar heights | Japan Post | |

|

KarTrak ACI | Discrete | Coloured bars | Used in North America on railroad rolling equipment |

| PostBar | Discrete | 4 bar heights | Canadian Post office | |

| POSTNET | Discrete | Tall/short | United States Postal Service (no international standard available) | |

|

RM4SCC / KIX | Discrete | 4 bar heights | Royal Mail / PostNL |

| RM Mailmark C | Discrete | 4 bar heights | Royal Mail | |

| RM Mailmark L | Discrete | 4 bar heights | Royal Mail | |

| Spotify codes | Discrete | 23 bar heights | Spotify codes point to artists, songs, podcasts, playlists, and albums. The information is encoded in the height of the bars;[43] so as long as the bar heights are maintained, the code can be handwritten and can vary in color.[44] Patented under EP3444755. |

Matrix (2D) codes

[edit]A matrix code or simply a 2D code, is a two-dimensional way to represent information. It can represent more data per unit area. Apart from dots various other patterns can be used.

| Example | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

App Clip Code | Apple-proprietary code for launching "App Clips", a type of applet. 5 concentric rings of three colors (light, dark, middle).[45] |

|

ArUco code | ArUco markers are black-and-white square patterns used as visual tags that can be easily detected and identified by a camera. They are commonly used in augmented reality, robotics, and camera calibration to determine the position and orientation of objects. Their design includes error correction, making them reliable even under partial occlusion or in challenging lighting conditions.[46] |

|

AR Code | A type of marker used for placing content inside augmented reality applications. Some AR Codes can contain QR codes inside, so that AR content can be linked to.[47] See also ARTag. |

|

Aztec Code | Designed by Andrew Longacre at Welch Allyn (now Honeywell Scanning and Mobility). Public domain. – International Standard: ISO/IEC 24778 |

|

bCode | A matrix designed for the study of insect behavior.[48] Encodes an 11 bit identifier and 16 bits of read error detection and error correction information. Predominantly used for marking honey bees, but can also be applied to other animals. |

|

BEEtag | A 25 bit (5x5) code matrix of black and white pixels that is unique to each tag surrounded by a white pixel border and a black pixel border. The 25-bit matrix consists of a 15-bit identity code, and a 10-bit error check.[49] It is designed to be a low-cost, image-based tracking system for the study of animal behavior and locomotion. |

|

BeeTagg | A 2D code with honeycomb structures suitable for mobile tagging developed by the Swiss company connvision AG. |

| Bokode | A type of data tag which holds much more information than a barcode over the same area. They were developed by a team led by Ramesh Raskar at the MIT Media Lab. The bokode pattern is a tiled series of Data Matrix codes. | |

|

Boxing | A high-capacity 2D code is used on piqlFilm by Piql AS[50] |

| Cauzin Softstrip | Softstrip code was used in the 1980s to encode software, which could be transferred by special scanners from printed journals into computer hardware. | |

|

Code 1 | Public domain. Code 1 is currently used in the health care industry for medicine labels and the recycling industry to encode container content for sorting.[51] |

|

ColorCode | ColorZip[52] developed colour barcodes that can be read by camera phones from TV screens; mainly used in Korea.[53] |

|

Color Construct Code | Color Construct Code is one of the few code symbologies designed to take advantage of multiple colors.[54][55] |

|

Cronto Visual Cryptogram | The Cronto Visual Cryptogram (also called photoTAN) is a specialized color barcode, spun out from research at the University of Cambridge by Igor Drokov, Steven Murdoch, and Elena Punskaya.[56] It is used for transaction signing in e-banking; the barcode contains encrypted transaction data which is then used as a challenge to compute a transaction authentication number using a security token.[57] |

|

CyberCode | CyberCode is a visual tagging system utilizing 2D barcodes, designed for recognition by standard cameras, enabling the identification and 3D positioning of tagged objects. Its design incorporates visual fiduciary markers, allowing computers to determine both the identity and orientation of objects, making it suitable for augmented reality applications. However, its data capacity is limited to 24 bits, restricting the amount of information each tag can convey. From Sony. |

| d-touch | Readable when printed on deformable gloves and stretched and distorted[58][59] | |

|

DataGlyphs | From Palo Alto Research Center (also termed Xerox PARC).[60]

Patented.[61] DataGlyphs can be embedded into a half-tone image or background shading pattern in a way that is almost perceptually invisible, similar to steganography.[62][63] |

|

Data Matrix | From Microscan Systems, formerly RVSI Acuity CiMatrix/Siemens. Public domain. Increasingly used throughout the United States. Single segment Data Matrix is also termed Semacode. – International Standard: ISO/IEC 16022. |

| Datastrip Code | From Datastrip, Inc. | |

| Digimarc code | The Digimarc Code is a unique identifier, or code, based on imperceptible patterns that can be applied to marketing materials, including packaging, displays, ads in magazines, circulars, radio and television[64] | |

| digital paper | Patterned paper used in conjunction with a digital pen to create handwritten digital documents. The printed dot pattern uniquely identifies the position coordinates on the paper. | |

| Dolby Digital | Digital sound code for printing on cinematic film between the threading holes | |

|

DotCode | Standardized as ISS DotCode Symbology Specification 4.0. Public domain. Extended 2D replacement of Code 128 barcode. At this time is used to track individual cigarette and pharmaceutical packages. |

| Dot Code A | Also known as Philips Dot Code.[65] Patented in 1988.[66] | |

| DWCode | Introduced by GS1 US and GS1 Germany, the DWCode is a unique, imperceptible data carrier that is repeated across the entire graphics design of a package[67] | |

|

EZcode | Designed for decoding by cameraphones;[68] from ScanLife.[69] |

|

Han Xin code | Code designed to encode Chinese characters, invented in 2007 by Chinese company The Article Numbering Center of China, introduced by Association for Automatic Identification and Mobility in 2011 and published as ISO/IEC 20830:2021 in 2021. |

|

High Capacity Color Barcode | HCCB was developed by Microsoft; licensed by ISAN-IA. |

| HueCode | From Robot Design Associates. Uses greyscale or colour.[70] | |

| InterCode | From Iconlab, Inc. The standard 2D Code in South Korea. All 3 South Korean mobile carriers put the scanner program of this code into their handsets to access mobile internet, as a default embedded program. | |

| JAB Code | Just Another Bar Code is a colored 2D Code. Square or rectangle. License free. | |

|

MaxiCode | Used by United Parcel Service. Now public domain. |

| mCode | Designed by NextCode Corporation, specifically to work with mobile phones and mobile services.[71] It is implementing an independent error detection technique preventing false decoding, it uses a variable-size error correction polynomial, which depends on the exact size of the code.[72] | |

|

Messenger Codes | Proprietary ring-shaped code for Facebook Messenger. Defunct as of 2019, replaced by standard QR codes. |

|

Micro QR code | Micro QR code is a smaller version of the QR code standard for applications where symbol size is limited. |

|

Micro PDF417 | MicroPDF417 is a restricted size barcode, similar to PDF417, which is used to add additional data to linear barcodes. |

| MMCC | Designed to disseminate high capacity mobile phone content via existing colour print and electronic media, without the need for network connectivity | |

|

NaviLens | NaviLens is a colour matrix barcode intended to help blind and visually impaired people find their way around railway and subway stations, museums, libraries, and other public spaces. |

|

NexCode | NexCode is developed and patented by S5 Systems. |

| Nintendo Dot code | Developed by Olympus Corporation to store songs, images, and mini-games for Game Boy Advance on Pokémon trading cards. | |

|

PDF417 | Originated by Symbol Technologies. Public domain. – International standard: ISO/IEC 15438 |

| Ocode | A proprietary matrix code in hexagonal shape.[73] | |

|

Qode | American proprietary and patented 2D Code from NeoMedia Technologies, Inc.[69] |

|

QR code | Initially developed, patented and owned by Denso Wave for automotive components management; they have chosen not to exercise their patent rights. Can encode Latin and Japanese Kanji and Kana characters, music, images, URLs, emails. De facto standard for most modern smartphones. Used with BlackBerry Messenger to pick up contacts rather than using a PIN code. The most frequently used type of code to scan with smartphones, and one of the most widely used 2D Codes.[74] Public domain. – International standard: ISO/IEC 18004 |

|

Rectangular Micro QR Code (rMQR Code) | Rectangular extension of QR Code Originated by Denso Wave. Public domain. – International standard: ISO/IEC 23941 |

| Screencode | Developed and patented[75][76] by Hewlett-Packard Labs. A time-varying 2D pattern using to encode data via brightness fluctuations in an image, for the purpose of high bandwidth data transfer from computer displays to smartphones via smartphone camera input. Inventors Timothy Kindberg and John Collomosse, publicly disclosed at ACM HotMobile 2008.[77] | |

|

ShotCode | Circular pattern codes for camera phones. Originally from High Energy Magic Ltd in name Spotcode. Before that most likely termed TRIPCode. |

|

Snapcode, also called Boo-R code | Used by Snapchat, Spectacles, etc. US9111164B1[78][79][80] |

| Snowflake Code | A proprietary code developed by Electronic Automation Ltd. in 1981. It is possible to encode more than 100 numeric digits in a space of only 5mm x 5mm. User selectable error correction allows up to 40% of the code to be destroyed and still remain readable. The code is used in the pharmaceutical industry and has an advantage that it can be applied to products and materials in a wide variety of ways, including printed labels, ink-jet printing, laser-etching, indenting or hole punching.[41][81][82] | |

|

SPARQCode | QR code encoding standard from MSKYNET, Inc. |

| TLC39 | This is a combination of the two barcodes Code 39 and MicroPDF417, forming a 2D pattern. It is also known as Telecommunications Industry Forum (TCIF) Code 39 or TCIF Linked Code 39.[83] | |

| Trillcode | Designed for mobile phone scanning.[84] Developed by Lark Computer, a Romanian company.[72] | |

| VOICEYE | Developed and patented by VOICEYE, Inc. in South Korea, it aims to allow blind and visually impaired people to access printed information. It also claims to be the 2D Code that has the world's largest storage capacity. | |

|

WeChat Mini Program code | A circular code with outward-projecting lines.[85] |

Example images

[edit]- First, second and third generation barcodes

-

GTIN-12 number encoded in UPC-A barcode symbol. First and last digit are always placed outside the symbol to indicate Quiet Zones that are necessary for barcode scanners to work properly

-

EAN-13 (GTIN-13) number encoded in EAN-13 barcode symbol. First digit is always placed outside the symbol, additionally right quiet zone indicator (>) is used to indicate Quiet Zones that are necessary for barcode scanners to work properly

-

"Wikipedia" encoded in Code 93

-

"*WIKI39*" encoded in Code 39

-

"Wikipedia" encoded in Code 128

-

An example of a stacked barcode. Specifically a "Codablock" barcode.

-

PDF417 sample

-

"This is an example Aztec symbol for Wikipedia" encoded in Aztec Code

-

Text 'EZcode'

-

High Capacity Color Barcode of the URL for Wikipedia's article on High Capacity Color Barcode

-

"Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia" in several languages encoded in DataGlyphs

-

Two different 2D barcodes used in film: Dolby Digital between the sprocket holes with the "Double-D" logo in the middle, and Sony Dynamic Digital Sound in the blue area to the left of the sprocket holes

-

MaxiCode example. This encodes the string "Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia"

-

ShotCode sample

-

detail of Twibright Optar scan from laser printed paper, carrying 32 kbit/s Ogg Vorbis digital music (48 seconds per A4 page)

-

A KarTrak railroad Automatic Equipment Identification label on a caboose in Florida

In popular culture

[edit]In architecture, a building in Lingang New City by German architects Gerkan, Marg and Partners incorporates a barcode design,[87] as does a shopping mall called Shtrikh-kod (Russian for barcode) in Narodnaya ulitsa ("People's Street") in the Nevskiy district of St. Petersburg, Russia.[88]

In media, in 2011, the National Film Board of Canada and ARTE France launched a web documentary entitled Barcode.tv, which allows users to view films about everyday objects by scanning the product's barcode with their iPhone camera.[89][90]

In professional wrestling, the WWE stable D-Generation X incorporated a barcode into their entrance video, as well as on a T-shirt.[91][92]

In video games, the protagonist of the Hitman video game series has a barcode tattoo on the back of his head; QR codes can also be scanned in a side mission in Watch Dogs. The 2018 videogame Judgment features QR Codes that protagonist Takayuki Yagami can photograph with his phone camera. These are mostly to unlock parts for Yagami's Drone.[93]

Interactive Textbooks were first published by Harcourt College Publishers to Expand Education Technology with Interactive Textbooks.[94]

Designed barcodes

[edit]Some companies integrate custom designs into barcodes on their consumer products without impairing their readability.

Opposition

[edit]Some have regarded barcodes to be an intrusive surveillance technology. Some Christians, pioneered by a 1982 book The New Money System 666 by Mary Stewart Relfe, believe the codes hide the number 666, representing the "Number of the beast".[95] Old Believers, a separation of the Russian Orthodox Church, believe barcodes are the stamp of the Antichrist.[96] Television host Phil Donahue described barcodes as a "corporate plot against consumers".[97]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b US patent 2612994

- ^ "How Barcodes Work". Stuff You Should Know. 4 June 2019. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ a b Cranstone, Ian. "A guide to ACI (Automatic Car Identification)/KarTrak". Canadian Freight Cars A resource page for the Canadian Freight Car Enthusiast. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Keyes, John (22 August 2003). "KarTrak". John Keyes Boston photoblogger. Images from Boston, New England, and beyond. John Keyes. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ a b Roberts, Sam (11 December 2019). "George Laurer, Who Developed the Bar Code, Is Dead at 94". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Brown, Derrick (Spring 2023). "The Birth of the Barcode". The Journal of the Computer Conservation Society (101). ISSN 0958-7403.

- ^ Brown, Derrick (20 March 2023). "The Birth of the Barcode". British Computer Society. Archived from the original on 6 August 2024. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (15 June 2011). "Alan Haberman, Who Ushered in the Bar Code, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ G. F. (2 November 2017). "Why QR codes are on the rise". The Economist. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ Fishman, Charles (1 August 2001). "The Killer App – Bar None". American Way. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Seideman, Tony (Spring 1993), "Barcodes Sweep the World", Wonders of Modern Technology, archived from the original on 16 October 2016

- ^ Dunn, Peter (20 October 2015). "David Collins, SM '59: Making his mark on the world with bar codes". technologyreview.com. MIT. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Graham-White, Sean (August 1999). "Do You Know Where Your Boxcar Is?". Trains. 59 (8): 48–53.

- ^ Laurer, George. "Development of the U.P.C. Symbol". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008.

- ^ Nelson, Benjamin (1997). Punched Cards To Bar Codes: A 200-year journey. Peterborough, N.H.: Helmers. ISBN 978-0-911261-12-7.

- ^ a b Varchaver, Nicholas (31 May 2004). "Scanning the Globe". Fortune. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ Rawsthorn, Alice (23 February 2010). "Scan Artists". New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "World hails barcode on important birthday". ATN. 1 July 2014. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "A Short History of Bar Code". BarCode 1. Adams Communications. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ "Barcode". iWatch Systems. 2 May 2011. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Oberfield, Craig. "QNotes Barcode System". US Patented #5296688. Quick Notes Inc. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ National Geographic, May 2010, page 30

- ^ Hecht, David L. (March 2001). "Printed Embedded Data Graphical User Interfaces" (PDF). IEEE Computer. 34 (3). Xerox Palo Alto Research Center: 47–55. Bibcode:2001Compr..34c..47H. doi:10.1109/2.910893. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2013.

- ^ Howell, Jon; Kotay, Keith (March 2000). "Landmarks for absolute localization" (PDF). Dartmouth Computer Science Technical Report TR2000-364. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020.

- ^ "IATA.org". IATA.org. 21 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ "Paperbyte Bar Codes for Waduzitdo". Byte magazine. September 1978. p. 172. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ "Nokia N80 Support". Nokia Europe. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011.

- ^ "package overview for mbarcode". Maemo.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Sargent, Mikah (24 September 2017). "How to use QR codes in iOS 11". iMore. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "15+ Best Barcode Scanner iPhone Applications". iPhoneness. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ David, H (28 November 2018), "Barcodes – Validation vs Verification in GS1", Labeling News, archived from the original on 7 June 2020, retrieved 6 June 2020

- ^ "Layman's Guide to ANSI, CEN, and ISO Barcode Print Quality Documents" (PDF). Association for Automatic Identification and Data Capture Technologies (AIM). 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Zieger, Anne (October 2003). "Retailer chargebacks: is there an upside? Retailer compliance initiatives can lead to efficiency". Frontline Solutions. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Corp, Express. "Barcode Glossary | Express". Express Corp. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Bar Code Verification Best Practice work team (May 2010). "GS1 DataMatrix: An introduction and technical overview of the most advanced GS1 Application Identifiers compliant symbology" (PDF). Global Standards 1. 1 (17): 34–36. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ GS1 Bar Code Verification Best Practice work team (May 2009). "GS1 Bar Code Verification for Linear Symbols" (PDF). Global Standards 1. 4 (3): 23–32. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Garner, J (2019), Results of Data Matrix Barcode Testing for Field Applications, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, retrieved 6 June 2020

- ^ "Technical committees – JTC 1/SC 31 – Automatic identification and data capture techniques". ISO. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Harmon, Craig K.; Adams, Russ (1989). Reading Between The Lines:An Introduction to Bar Code Technology. Peterborough, NH: Helmers. p. 13. ISBN 0-911261-00-1.

- ^ "Barcoding fact sheet" (PDF). Australia Post. October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2024.

- ^ a b "2-Dimensional Bar Code Page". www.adams1.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Code 16K Specs" (PDF). www.gomaro.ch. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Boone, Peter (13 November 2020). "How do Spotify Codes work?". boonepeter.github.io. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Scan these new QR-style Spotify Codes to instantly play a song". TechCrunch. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Creating App Clip Codes". Apple Developer Documentation.

- ^ "OpenCV: Detection of ArUco Markers". Open Source Computer Vision.

- ^ ""AR Code Generator"". Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Gernat, Tim; Rao, Vikyath D.; Middendorf, Martin; Dankowicz, Harry; Goldenfeld, Nigel; Robinson, Gene E. (13 February 2018). "Automated monitoring of behavior reveals bursty interaction patterns and rapid spreading dynamics in honeybee social networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (7): 1433–1438. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.1433G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713568115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5816157. PMID 29378954.

- ^ Combes, Stacey A.; Mountcastle, Andrew M.; Gravish, Nick; Crall, James D. (2 September 2015). "BEEtag: A Low-Cost, Image-Based Tracking System for the Study of Animal Behavior and Locomotion". PLOS ONE. 10 (9) e0136487. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1036487C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136487. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4558030. PMID 26332211.

- ^ "GitHub – piql/Boxing: High capacity 2D barcode format". GitHub. 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Adams, Russ (15 June 2009). "2-Dimensional Bar Code Page". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Colorzip.com". Colorzip.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ "Barcodes for TV Commercials". Adverlab. 31 January 2006. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "About". Colour Code Technologies. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". ColorCCode. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "New system to combat online banking fraud". University of Cambridge. University of Cambridge. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Cronto Visual Transaction Signing, OneSpan, archived from the original on 6 December 2019, retrieved 6 December 2019

- ^ d-touch topological fiducial recognition, MIT, archived from the original on 2 March 2008.

- ^ d-touch markers are applied to deformable gloves, MIT, archived from the original on 21 June 2008.

- ^ See Xerox.com Archived 7 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine for details.

- ^ "DataGlyphs: Embedding Digital Data". Microglyphs. 3 May 2006. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ ""DataGlyph" Embedded Digital Data". Tauzero. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ "DataGlyphs". Xerox. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ "Better Barcodes, Better Business" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Dot Code A Archived 9 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine at barcode.ro

- ^ "Dot Code A Patent" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "GS1 Germany and Digimarc Announce Collaboration to Bring DWCode to the German Market" (Press release).

- ^ "Scanbuy". Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ a b Steeman, Jeroen. "Online QR Code Decoder". Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "BarCode-1 2-Dimensional Bar Code Page". Adams. Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Global Research Solutions – 2D Barcodes". grs.weebly.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ a b Kato, Hiroko; Tan, Keng T.; Chai, Douglas (8 April 2010). Barcodes for Mobile Devices. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48751-1.

- ^ "Ocode – Authentifiez vos produits par le marquage d'un code unique". www.ocode.fr (in French). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Chen, Rongjun; Yu, Yongxing; Xu, Xiansheng; Wang, Leijun; Zhao, Huimin; Tan, Hong-Zhou (11 December 2019). "Adaptive Binarization of QR Code Images for Fast Automatic Sorting in Warehouse Systems". Sensors. 19 (24): 5466. Bibcode:2019Senso..19.5466C. doi:10.3390/s19245466. PMC 6960674. PMID 31835866.

- ^ ""US Patent 9270846: Content encoded luminosity modulation"". Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ ""US Patent 8180163: Encoder and decoder and methods of encoding and decoding sequence information with inserted monitor flags"". Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ ""Screen Codes: Visual Hyperlinks for Displays"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ ""Snapchat is changing the way you watch snaps and add friends"". July 2015. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ ""Snapchat Lets You Add People Via QR Snaptags Thanks To Secret Scan.me Acquisition"". 28 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ ""How Snapchat Made QR Codes Cool Again"". 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ US 5825015, Chan, John Paul & GB, "Machine readable binary codes", issued 20 October 1998

- ^ "US Patent 5825015". pdfpiw.uspto.gov. 20 October 1998. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Understanding TLC-39 Barcodes: All You Need to Know". 9 August 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Trillcode Barcode". Barcoding, Inc. 17 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Getting Mini Program Code". Weixin public doc.

- ^ (株)デンソーウェーブ Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, denso-wave.com (in Japanese) Copyright

- ^ "Barcode Halls, Standard Facades for Manufacturing Buildings – Projects – gmp Architekten". www.gmp.de. 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "image". Peterburg2.ru. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Lavigne, Anne-Marie (5 October 2011). "Introducing Barcode.tv, a new interactive doc about the objects that surround us". NFB Blog. National Film Board of Canada. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ Anderson, Kelly (6 October 2011). "NFB, ARTE France launch 'Bar Code'". Reelscreen. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ [1] Archived 16 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dx theme song 2009–2010". YouTube. 19 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Diego Agruello (27 June 2019). "Judgment QR code locations to upgrade Drone Parts explained • Eurogamer.net". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ "CueCat History". CueCat History. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "What about barcodes and 666: The Mark of the Beast?". Av1611.org. 1999. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Serafino, Jay (26 July 2018). "The Russian Family That Cut Itself Off From Civilization for More Than 40 Years". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Bishop, Tricia (5 July 2004). "UPC bar code has been in use 30 years". SFgate.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2004. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Automating Management Information Systems: Barcode Engineering and Implementation – Harry E. Burke, Thomson Learning, ISBN 0-442-20712-3

- Automating Management Information Systems: Principles of Barcode Applications – Harry E. Burke, Thomson Learning, ISBN 0-442-20667-4

- The Bar Code Book – Roger C. Palmer, Helmers Publishing, ISBN 0-911261-09-5, 386 pages

- The Bar Code Manual – Eugene F. Brighan, Thompson Learning, ISBN 0-03-016173-8

- Handbook of Bar Coding Systems – Harry E. Burke, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, ISBN 978-0-442-21430-2, 219 pages

- Information Technology for Retail:Automatic Identification & Data Capture Systems – Girdhar Joshi, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-569796-0, 416 pages

- Lines of Communication – Craig K. Harmon, Helmers Publishing, ISBN 0-911261-07-9, 425 pages

- Punched Cards to Bar Codes – Benjamin Nelson, Helmers Publishing, ISBN 0-911261-12-5, 434 pages

- Revolution at the Checkout Counter: The Explosion of the Bar Code – Stephen A. Brown, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-76720-9

- Reading Between The Lines – Craig K. Harmon and Russ Adams, Helmers Publishing, ISBN 0-911261-00-1, 297 pages

- The Black and White Solution: Bar Code and the IBM PC – Russ Adams and Joyce Lane, Helmers Publishing, ISBN 0-911261-01-X, 169 pages

- Sourcebook of Automatic Identification and Data Collection – Russ Adams, Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 0-442-31850-2, 298 pages

- Inside Out: The Wonders of Modern Technology – Carol J. Amato, Smithmark Pub, ISBN 0831746572, 1993

![The QR code for the Wikipedia URL. "Quick Response", the most popular 2D barcode. It is open in that the specification is disclosed and the patent is not exercised.[86]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/WikiQRCode.svg/120px-WikiQRCode.svg.png)