Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Behemoth

View on Wikipedia

Behemoth (/bɪˈhiːməθ, ˈbiːə-/; Hebrew: בְּהֵמוֹת, bəhēmōṯ) is a beast from the biblical Book of Job, and is a form of the primeval chaos-monster created by God at the beginning of creation. Metaphorically, the name has come to be used for any extremely large or powerful entity.

Etymology

[edit]The Hebrew word behemoth has the same form as the plural of the Hebrew noun בהמה behemah, meaning "beast", suggesting an augmentative meaning "great beast". However, some theorize that the word might originate from an Egyptian word of the form pꜣ jḥ mw "the water-ox", meaning "hippopotamus", altered by folk etymology in Hebrew to resemble behemah.[1] However, this phrase with this meaning is unattested at any stage of Egyptian.[2] Even before the decipherment of Ancient Egyptian in the early 19th century, there was widespread identification of the biblical behemoth with the hippopotamus. The word for "hippopotamus" in Russian remains derivative of behemoth (бегемот), a meaning that entered the language in the mid-18th century.[3][4]

Biblical description

[edit]

The Hebrew word behemoth is mentioned only once in Biblical text, in a speech from the mouth of God in the Book of Job. It is a primeval creature created by God and so powerful that only God can overcome him:[5]

Take now behemoth, whom I made as I did you;

He eats grass, like the cattle.

His strength is in his loins,

His might in the muscles of his belly.

He makes his tail stand up like a cedar;

The sinews of his thighs are knit together.

His bones are like tubes of bronze,

His limbs like iron rods.

He is the first of God’s works;

Only his Maker can draw the sword against him.

The mountains yield him produce,

Where all the beasts of the field play.

He lies down beneath the lotuses,

In the cover of the swamp reeds.

The lotuses embower him with shade;

The willows of the brook surround him.

He can restrain the river from its rushing;

He is confident the stream will gush at his command.

Can he be taken by his eyes?

Can his nose be pierced by hooks?

— Job 40:15-24[6]

The passage later pairs Behemoth with the sea-monster Leviathan, both composite mythical creatures with enormous strength that humans could not hope to control, yet both are reduced to the status of divine pets.[7]

Later interpretations

[edit]In Jewish apocrypha and pseudepigrapha, such as the 2nd century BC Book of Enoch (60:7–10), Behemoth is the unconquerable male land-monster, living in an invisible desert (Duidain) east of the Garden of Eden, as Leviathan is the primeval female sea-monster, dwelling in "the Abyss", and Ziz the primordial sky-monster. Similarly, in the most ancient section of the Second Book of Esdras (6:47–52), written around AD 100 (3:1), the two are described as inhabiting the mountains and the seas, respectively, after being separated from each other, due to the sea's insufficiency to contain them both. Likewise, in the contemporaneous Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch (29:4), it is stated that Behemoth will come forth from his seclusion on land, and Leviathan out of the sea, and that the two gigantic monsters, created on the fifth day, will serve as food for the elect, who will survive in the days of the Messiah.[8]

A Jewish rabbinic legend describes a great battle that will take place between them at the end of time: "they will interlock with one another and engage in combat, with his horns the Behemoth will gore with strength, the fish [Leviathan] will leap to meet him with his fins, with power. Their Creator will approach them with his mighty sword [and slay them both];" then, "from the beautiful skin of the Leviathan, God will construct canopies to shelter the righteous, who will eat the meat of the Behemoth and the Leviathan amid great joy and merriment." In the Haggadah, Behemoth's strength reaches its peak on the summer solstice of every solar year (around 21 June). At this time of year, Behemoth lets out a loud roar that makes all animals tremble with fear, and thus renders them less ferocious for a whole year. As a result, weak animals live in safety away from the reach of wild animals. This mythical phenomenon is shown as an example of divine mercy and goodness. Without Behemoth's roar, traditions narrate, animals would grow more wild and ferocious, and hence go around butchering each other and humans.[9]

Modern interpretations of Behemoth tend to fall into several categories:

- Behemoth is an animal of the modern natural world, most often the hippopotamus (e.g. in Russian where the word begemot refers more often to hippopotamus rather than the Biblical animal), although the elephant and water buffalo could also be candidates. All three consume grass and chew it as an ox would, and the elephant and water buffalo both have mobile, sprucy tails that sway in a similar manner to a Lebanese cedar-tree sapling (though the text does not specify a sapling).

- Behemoth was an invention of the poet who wrote the Book of Job.

- Behemoth and Leviathan were both separate mythical chaos-beasts.[10]

Additionally, some creationist fundamentalists, such as the Christian organization Answers in Genesis, claim that the Behemoth is some species of sauropod or other dinosaur based on the comparison of the tail to a cedar tree.[11]

Literary references

[edit]This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2024) |

The 17th-century political philosopher Thomas Hobbes named the Long Parliament 'Behemoth' in his book Behemoth. It accompanies his book of political theory that draws on the lessons of English Civil War, the rather more famous Leviathan.

The Dictionnaire Infernal version of Behemoth is a demon that resembles a round-bellied humanoid elephant. He works as the infernal watchman for Satan and oversees the banquets in Hell while having a good singing voice.

The Behemoth is also mentioned in the opera, Nixon in China, composed by John Adams, and written by Alice Goodman. At the beginning of the first act, the chorus sings "The people are the heroes now, Behemoth pulls the peasants' plow" several times.[12]

The Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov used a demonic cat with the name Behemoth as a character in his novel The Master and Margarita. In the book the cat could speak and walk on two legs and was part of the entourage of Woland, who represented Satan.

The webnovel Worm features the Endbringers, a trio of city-destroying monsters named Behemoth, Leviathan and the Simurgh.

See also

[edit]- Bamot

- Bahamut

- Bambotus, ancient name for the Senegal River

- The Beast (Revelation), two beasts described in the New Testament

- Dābbat al-Arḍ

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- The Giant Behemoth, an American-British science fiction giant monster film

- Tarasque

- Hadhayosh

- Behemoth (novel), novel by Scott Westerfeld

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "behemoth, n.". OED Online. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ "Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae - Login". aaew2.bbaw.de. Archived from the original on 2022-09-27. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- ^ "бегемот translations, 6 examples and declension". en.openrussian.org. Retrieved 2025-02-04.

- ^ "Словарь Академии Российской". runivers.ru. Retrieved 2025-02-04.

- ^ Dell 2003, p. 362.

- ^ "Job 40:15–16". www.sefaria.org.

- ^ Coogan 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Hirsch, Emil G.; Kohler, Kaufmann; Schechter, Solomon; Broydé, Isaac. "Leviathan and Behemoth". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Ginzberg 2006, p. 43–49.

- ^ Uehlinger 1999, p. 166–167.

- ^ Steel, Allan (1 August 2001). "Could Behemoth Have Been a Dinosaur?". Answers in Genesis. Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- ^ Goodman, Alice (21 February 1972). Nixon in China. Libretto (opera lyrics). Adams, John (score). Retrieved 4 February 2014 – via Opera-Arias.com.

Bibliography

[edit]- Coogan, Michael D. (2004). "Behemoth". In Metzger, Michael David, Bruce Manning; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176100.

- Dell, Katharine J. (2003). "Job". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Ginzberg, Louis (2006). Legends of the Jews. Vol. V. Cosimo. ISBN 9781596057920.

- Uehlinger, C. (1999). "Behemoth". In Toorn, Karel van der; Becking, Bob (eds.). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802824912.

Behemoth

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Etymology

Linguistic Roots

The term "Behemoth" originates from the Hebrew word בְּהֵמוֹת (bəhēmôṯ), an intensive plural form of בְּהֵמָה (bəhēmâ), which denotes "beast," "animal," or "cattle." This plural construction functions as an augmentative, emphasizing superlative size or monstrous proportions, akin to a "beast of beasts" or "great beast."[5][6] Scholars have proposed possible external influences on the term, including an Egyptian etymology from *pꜣ-jḥ-mw (p-ehe-mau), meaning "water-ox" and referring to the hippopotamus, though this connection remains debated and was rejected by some linguists like W. Max Müller due to phonetic and morphological discrepancies.[6] In ancient translations, the Septuagint rendered bəhēmôṯ as θηρίον (thēríon), the Greek term for "wild beast," generalizing it within the context of Job 40:15 without preserving the Hebrew specificity. The Latin Vulgate, translated by Jerome, transliterated it directly as "behemoth," maintaining the original form in Job 40:15. This Latin version influenced subsequent European renderings, culminating in the English King James Bible of 1611, which adopted "behemoth" verbatim, introducing the term into modern languages.[7][8][9] Post-biblically, in Hebrew and Aramaic texts like the Targums and rabbinical literature, bəhēmôṯ evolved semantically to denote a primeval monster or king of land beasts, often in eschatological contexts such as the Messianic banquet. Phonetically, it adapted in European languages through Latin intermediaries, with semantic shifts toward metaphorical uses signifying overwhelming power or chaos, as seen in English by the 19th century where "behemoth" broadly describes any colossal entity.[6][5]Biblical Context

Behemoth is introduced in the Hebrew Bible within the Book of Job, specifically in verses 40:15–24, as part of God's extended address to Job from the whirlwind. This passage occurs during the divine speeches that form the climax of the poetic section, following God's initial rhetorical questions about the foundations of the earth and the governance of natural phenomena in chapters 38–39, and immediately preceding the depiction of Leviathan in chapter 41. The narrative frames Behemoth as a creature made by God alongside Job himself, emphasizing its role within the broader discourse on creation. The Book of Job, part of the Wisdom literature tradition in the Hebrew Bible, is attributed to an anonymous author or authors and is generally dated by scholars to the 6th–4th centuries BCE, likely composed during or after the Babylonian Exile.[10] This timeframe aligns with linguistic features that resonate with exilic and post-exilic prophetic texts, such as echoes of Second Isaiah, while the prose frame (chapters 1–2 and 42) may reflect an earlier folkloric core expanded by later poetic insertions.[10] In the narrative structure, the description of Behemoth serves to underscore God's unparalleled creative authority and mastery over the wildest elements of the natural order, creatures that dwell peacefully under divine provision yet remain untamable by human hands.[11] This portrayal contrasts Job's quest for justification amid suffering with the vast, inscrutable scope of divine wisdom, prompting Job's eventual submission and restoration by highlighting humanity's limited perspective relative to God's dominion.[2] The primary textual witness for Job 40:15–24 is the Masoretic Text, the standardized Hebrew version from the 7th–10th centuries CE, which emphasizes Behemoth's habitat among reeds and rivers as a place of security under God's eye.[12] Surviving Dead Sea Scrolls fragments of Job (primarily from caves 4 and 11, dated 2nd century BCE–1st century CE) preserve portions of the book but do not include this specific passage, though where extant, they demonstrate close alignment with the Masoretic phrasing and overall content, suggesting textual stability in the tradition.[13]Biblical Description

Physical Attributes

In the Book of Job, Behemoth is described as a massive creature created by God alongside humanity, emphasizing its formidable physical presence through vivid poetic imagery. It is portrayed as an herbivore that "feeds on grass like an ox," with extraordinary strength evident in its loins and the powerful muscles of its belly.[14] Its tail sways like a cedar tree, a striking metaphor for its size and flexibility, while the sinews of its thighs are tightly knit for unyielding support.[14] The creature's skeletal structure is likened to tubes of bronze for its bones and rods of iron for its limbs, underscoring an almost indestructible robustness.[14] Behemoth's habitat is depicted as aquatic and riparian, dwelling securely in marshy environments where it lies hidden under lotus plants amid reeds and surrounded by poplars along streams.[14] It remains unalarmed by raging rivers or even the surging Jordan flooding its mouth, suggesting an amphibious nature adapted to watery domains without fear of inundation.[14] For sustenance, it grazes on the produce brought forth by hills, with wild animals playing nearby, reinforcing its role as a dominant yet peaceful herbivore in mountainous and riverine landscapes.[14] The text ranks Behemoth as "first among the works of God," highlighting its unparalleled scale and power, accessible only to its Creator with a sword, while humans lack the means to approach or subdue it.[14] Verses 15-24 poetically illustrate its movements—tail swaying gracefully, body emerging from concealment—and invulnerability, as no one can capture it by sight alone or trap and pierce its nose, evoking an image of majestic, untamable might.[14] This portrayal serves as a divine exemplar in Job's dialogue, showcasing God's sovereignty over creation's grandest forms.Symbolic Role

In the Book of Job, Behemoth serves as a potent symbol of primordial chaos subdued by divine order, echoing ancient Near Eastern myths such as the Babylonian Enuma Elish and Ugaritic tales where deities like Marduk or Baal battle massive beasts representing disorder to establish cosmic stability.[15] Unlike those narratives, however, Job portrays Behemoth not as an adversarial force overcome in a primordial conflict but as a creature fully under Yahweh's dominion, emphasizing creation's inherent harmony rather than a violent conquest.[16] This depiction underscores the theological theme of Yahweh's absolute sovereignty, as God invokes Behemoth in Job 40:15-24 to humble the protagonist by demonstrating mastery over even the most formidable elements of the natural world, thereby addressing Job's existential questions about suffering without providing direct explanations.[16] Behemoth functions as the terrestrial counterpart to Leviathan, the aquatic chaos monster described in Job 41, together reinforcing biblical motifs of dualistic creation where land and sea threats are tamed by the creator.[15] This pairing evokes broader scriptural imagery, such as Psalm 74:13-14, where Yahweh crushes sea dragons, but in Job, it highlights ongoing divine control rather than eschatological judgment, affirming that all creation—chaotic or otherwise—exists at God's pleasure.[6] Early Jewish exegesis in rabbinic literature, particularly the Midrash, interprets Behemoth's role in the messianic era. In texts like Bava Batra 74a, Behemoth's flesh is reserved for a banquet for the righteous at the advent of the Messiah, signifying divine provision and triumph over worldly forces.[6] Additionally, midrashic traditions in Vayikra Rabbah 13:3 portray the righteous hunting Behemoth, symbolizing enjoyment and divine triumph in the Messianic age rather than pagan sports.[6]Historical Interpretations

Ancient and Medieval Views

In ancient Jewish exegesis, Behemoth was often viewed as a primeval creature preserved for eschatological purposes, such as the Messianic banquet described in rabbinic literature. Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki), in his 11th-century commentary on Job 40:15, interprets "Behemoth" as a beast "prepared for the future," emphasizing its role in divine plans rather than a specific zoological identification, though later traditions drew on the biblical description to associate it with large river-dwelling animals like the hippopotamus. [17] [6] The Zohar, the foundational 13th-century kabbalistic text attributed to Moses de León, offers an esoteric interpretation, portraying Behemoth as a cosmic force tied to the material world and demonic influences, symbolizing the untamed energies of creation that must be subdued in the divine order. This view aligns with broader kabbalistic themes of balancing chaotic primordial elements. [18] Early Christian patristic writers employed allegorical methods to interpret Behemoth. Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE), in works like The Literal Meaning of Genesis and City of God, took a more naturalistic approach, linking Behemoth to known animals such as the hippopotamus to illustrate God's power over creation, while still noting its moral lessons against carnal excess. [19] In the medieval period, Thomas Aquinas, in his Commentary on Job, allegorized Behemoth as a metaphor for the devil or carnal desires, emphasizing its role in demonstrating human limitations before divine wisdom.[20] Islamic traditions parallel Behemoth with Bahamut, a colossal fish or whale in medieval cosmography that supports the earth on its back, preventing cosmic collapse. This concept appears in the 11th-century Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ by al-Thaʿlabī, where Bahamut (sometimes called Lutiya) is subdued by God and integrated into the foundational structure of the world, echoing themes of divine control over chaotic forces. [21] In European medieval bestiaries, Behemoth was frequently depicted as a monstrous land beast ridden by a demon, serving as a moral symbol of gluttony and uncontrolled appetite, warning against the sin of overindulgence in earthly pleasures. The 12th-century Aberdeen Bestiary, for example, illustrates such creatures in contexts that emphasize ethical lessons, aligning with the Physiologus tradition of using animals for Christian moral instruction. [22] [23]Early Modern Perspectives

During the Reformation era, Martin Luther's 1545 translation of the Bible promoted a literalist approach to Scripture, interpreting Behemoth in Job 40 as a real creature, potentially an extinct land animal known to ancient observers, to underscore God's sovereignty over creation.[24] This view aligned with the period's emphasis on the Bible's historical accuracy, bridging medieval symbolism with emerging empirical observation, where Behemoth served as evidence of divine power manifested in tangible beasts.[25] In 17th-century natural history, scholars began integrating biblical descriptions with observed fauna. Edward Topsell's Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes (1607) symbolically associated Behemoth with the elephant, highlighting its immense strength and grass-eating habits as emblematic of Job's passage, while incorporating classical and contemporary accounts of exotic animals.[26] Similarly, John Jonston's Historiae Naturalis de Quadrupedibus (1650) illustrated Behemoth as akin to a rhinoceros or buffalo, classifying it among large herbivores to reconcile scriptural text with emerging zoological catalogs.[27] These works marked a proto-scientific shift, treating Behemoth as a historical species rather than pure allegory. The 18th century's rationalist Enlightenment brought skepticism toward biblical literalism. Voltaire, in his critiques of the Old Testament, derided the Behemoth description as mythological exaggeration, portraying it as an Oriental fable inflated for poetic effect to humble human presumption, as seen in his broader assaults on scriptural inconsistencies.[28] Concurrently, Carl Linnaeus's taxonomic system influenced tentative classifications of biblical beasts, aligning Behemoth with pachydermatous mammals like elephants or rhinoceroses under orders emphasizing thick hides and herbivorous diets, reflecting efforts to systematize ancient references within natural philosophy.[29] By the 19th century, biblical criticism advanced source analysis. Building on documentary methods, scholars questioned the Book of Job's compositional unity, viewing the Behemoth pericope (Job 40:15–24) as a possible later interpolation added to the poetic dialogues during the post-exilic period to enhance theological motifs of divine mastery over chaos.[30] This perspective integrated linguistic and historical evidence, prioritizing textual evolution over literal historicity.Modern Interpretations

Scientific and Zoological Theories

One of the most enduring zoological interpretations identifies Behemoth with the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), a view advanced by 20th-century biblical scholars including Robert Gordis in his commentary The Book of Job. This hypothesis aligns with the biblical portrayal of Behemoth as a grass-eating creature (Job 40:15) that dwells among reeds and rivers (Job 40:21–23), reflecting the hippopotamus's herbivorous diet and semi-aquatic habitat in ancient Near Eastern river systems. Gordis emphasized these behavioral and ecological matches as evidence of the text's grounding in observable wildlife known to the author.[31] However, this identification faces challenges, particularly the description of Behemoth's tail as "like a cedar" (Job 40:17), which contrasts with the hippopotamus's short, thin appendage measuring only about 35–50 cm in length; scholars note this poetic exaggeration may emphasize strength rather than literal anatomy but still creates a mismatch. Alternative zoological proposals include the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) or white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum), as suggested in modern study Bibles like the NIV Study Bible, which highlight anatomical parallels such as massive bone structure—"bones like bars of iron" and "limbs like rods of bronze" (Job 40:18)—capable of supporting immense weight up to 6,000 kg for elephants or 3,600 kg for rhinoceroses. These large herbivores also graze on grass like oxen (Job 40:15), and their robust limbs and overall scale position them as "chief of the ways of God" (Job 40:19) among terrestrial mammals, though the tail description again poses interpretive difficulties, potentially referring poetically to the elephant's trunk or the rhinoceros's stubby tail.[32][33] In paleontological circles, particularly among young-earth creationists, Behemoth has been linked to extinct sauropod dinosaurs like Brachiosaurus, a theory articulated by Henry M. Morris in The Genesis Record (1976), who compared the cedar-like tail to the long, whip-like tails of sauropods reaching up to 12 meters and capable of high-speed movement. Morris argued that the creature's enormous size, with bones strong enough to support a body over 20 meters long and weighing 30–50 tons, fits the text's emphasis on unmatched terrestrial power (Job 40:19), suggesting post-Flood survival of dinosaurs into human history. This interpretation gained broader popular traction following the 1993 release of Jurassic Park, which revitalized public fascination with dinosaurs and encouraged retroactive biblical associations in non-academic discussions.[34] Critiques of these theories underscore significant anachronisms and evidential gaps: the Book of Job, composed between the 7th and 4th centuries BCE, predates the 19th-century discovery of dinosaurs by Richard Owen, making direct reference to sauropods implausible without modern paleontological knowledge. Moreover, 21st-century fossil records confirm sauropod extinction around 66 million years ago at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, with no transitional forms or DNA evidence linking them to biblical-era fauna, while living candidates like the hippopotamus or elephant fail to match all attributes simultaneously, such as the tail or habitat versatility. These discrepancies lead many scholars to view the descriptions as hyperbolic depictions of familiar animals rather than precise zoological portraits.[35]Mythological and Cryptozoological Views

In mythological traditions, Behemoth is often interpreted as a land-based chaos monster paralleling ancient Near Eastern deities, such as the Babylonian Tiamat, whose serpentine form embodied primordial disorder subdued by divine order.[36] This connection draws from shared motifs in Semitic lore, where Behemoth represents untamed terrestrial forces, contrasting with sea-dwelling counterparts like Leviathan.[37] Similarly, Egyptian mythology links Behemoth-like descriptions to the god Set, depicted in hippo form as a chaotic entity battling order, with the Hebrew term "behemoth" echoing the Egyptian "pehemu," denoting a massive water ox or hippopotamus symbolizing destructive power.[38] Cryptozoological speculation in the mid-20th century positioned Behemoth as a potential surviving megaherbivore, with Belgian zoologist Bernard Heuvelmans describing reports of elephant-killing beasts in the Congo Basin during the 1950s, terming one the "Emela-ntouka" or "Congo Behemoth" in his 1978 work Les Derniers Dragons d'Afrique.[39] Heuvelmans, a foundational figure in cryptozoology, cataloged these as horned, rhinoceros-like herbivores evading extinction, based on indigenous accounts from the Likouala region.[40] Later explorers, such as Roy Mackal in his 1987 expedition reports, extended this to the Mokele-mbembe legend, a long-necked swamp dweller in Congolese folklore, proposing it as a modern echo of Behemoth through shared traits like immense size and riverine habitat.[40] Esoteric interpretations within 19th-century Theosophy, founded by Helena Blavatsky, frame Behemoth as a relic of Atlantean eras, symbolizing the degenerate fauna of the fourth root-race destroyed in cataclysms, as outlined in her 1888 The Secret Doctrine.[41] Blavatsky's cosmology posits such biblical beasts as distorted memories of pre-human evolutionary stages, blending chaos symbolism with lost continent lore. Post-2000 pseudoscientific theories, prevalent in young-earth creationist circles, recast Behemoth as a pre-Flood monster tied to Nephilim hybrids—offspring of fallen angels and humans—whose genetic corruption allegedly produced aberrant mega-fauna before Noah's deluge.[42] Proponents, including authors like Brian Godawa in his 2010s series on ancient myths, argue these hybrids explain Job's description as evidence of rapid post-Edenic speciation, aligning with a 6,000-year timeline where dinosaurs coexisted with early humans.[43] Online forums and publications from organizations like Answers in Genesis reinforce this by portraying Behemoth as a sauropod-like survivor of Edenic perfection warped by angelic rebellion.[44]Cultural Depictions

In Literature and Poetry

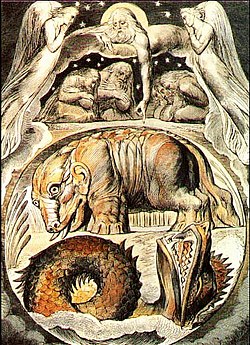

Behemoth originates as a literary figure in the Book of Job (Job 40:15–24), where it serves as a divine exemplar of untamable natural power, challenging human comprehension of God's creation and underscoring themes of humility and cosmic order.[45] In early modern literature, John Milton invokes Behemoth in Paradise Lost (1667), Book VII, as part of Raphael's account of creation: "Behemoth, biggest born of earth, upheaved / His vastness." Here, the creature embodies the raw, primordial forces shaped into divine harmony, contrasting chaos with ordered cosmos to illustrate God's sovereignty over all matter.[46] William Blake reimagines Behemoth in his 1825 engravings for Illustrations of the Book of Job, particularly plate 15, "Behold now Behemoth," portraying it as a coiled, vital energy symbolizing the dynamic interplay of divine imagination and earthly vitality in human experience. Blake's depiction, integrated with biblical verse, elevates the beast to a prophetic emblem of creative exuberance amid suffering.[47] Nineteenth-century works draw on Behemoth for explorations of nature's immensity and human insignificance. Herman Melville alludes to biblical monsters like Behemoth in Moby-Dick (1851), where the white whale evokes Job's land-sea ambiguities, representing evolutionary strife and uncontrollable forces; scholarly analysis positions Behemoth as the whale's terrestrial counterpart, amplifying themes of monstrous scale in a post-Darwinian world.[48] Alfred Lord Tennyson's In Memoriam A.H.H. (1850) indirectly engages such motifs through reflections on nature's brutality and evolutionary flux, though without direct naming, aligning Behemoth-like imagery with grief over lost order.[49] Twentieth-century authors adapt Behemoth metaphorically for speculative and theological ends. C.S. Lewis references it in his poem "Le Roi S'Amuse" (published posthumously in Poems, 1964), envisioning "gay Behemoth on a sable field" amid resurrected creation, symbolizing joyful renewal in a Christian eschatology where beasts partake in divine festivity.[50] In Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy (1995–2000), daemons echo Behemoth as archetypal animal-soul companions, embodying primal instincts and human-nature bonds in a multiverse of moral conflict, though not explicitly named.[51] Contemporary literature twists Behemoth into eco-horror paradigms. Jeff VanderMeer's Dead Astronauts (2019) features "Botch Behemoth," a colossal, mutating entity born from corporate biotech ruin, embodying environmental collapse and the grotesque fusion of technology with biblical monstrosity. Seamus Heaney's poetry, such as in Human Chain (2010), adapts ancient beast motifs in explorations of human-nature tensions, evoking Behemoth's scale in bog-preserved relics to meditate on historical violence and ecological memory.In Art, Film, and Media

In medieval illuminated manuscripts, Behemoth is frequently portrayed as a formidable, hybrid beast embodying chaos and divine creation from the Book of Job. One notable depiction appears in the 12th-century Liber Floridus, a encyclopedic manuscript compiled by Lambert of Saint-Omer, where Satan rides a massive, horned Behemoth-like creature, emphasizing its role as a symbol of infernal power subdued by God.[52] This representation aligns with broader medieval bestiary traditions, where Behemoth is illustrated as an ox-like monster with exaggerated strength to illustrate biblical themes of God's sovereignty over nature.[53] During the Renaissance, artistic interpretations of Behemoth remained sparse but influential in symbolic engravings and sketches exploring biblical mythology. Although no confirmed sketches of Behemoth by Albrecht Dürer exist, his detailed studies of fantastical creatures in works like the Apocalypse series (1498) influenced later depictions of biblical monsters, blending realism with mythic exaggeration.[54] In 19th- and 20th-century illustrations, Behemoth gained more realistic yet dramatic portrayals in biblical art. Gustave Doré's 1866 engravings for La Grande Bible de Tours include a striking image of Behemoth as a massive, hippopotamus-inspired beast emerging from reeds, capturing its immense tail "like a cedar" and herbivorous might from Job 40:15–24 to evoke awe at divine creation.[55] This style carried into modern comics, such as Mike Mignola's Hellboy series, where Behemoth is depicted as a demonic, tentacled spawn of the Ogdru Jahad, reimagined as an apocalyptic harbinger tied to occult lore.[56] Behemoth features in film and television as a symbol of ancient mysteries, often blending biblical literalism with speculative effects. Documentaries like Ancient Aliens (2009–present) on the History Channel portray Behemoth as evidence of extraterrestrial engineering or lost megafauna, linking it to ancient astronaut theories in episodes exploring biblical giants and chaos monsters.[57] In video games and contemporary media, Behemoth manifests as an interactive antagonist drawing from its mythic ferocity. The Polish black metal band Behemoth, formed in 1991, explicitly references the creature in its name and lyrics, subverting biblical imagery—such as inverting passages from Job and Revelation—to critique religious dogma, as seen in tracks like "Blow Your Trumpets Gabriel" from The Satanist (2014).[58]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Book_of_Enoch_(Charles)/Chapter_60