Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

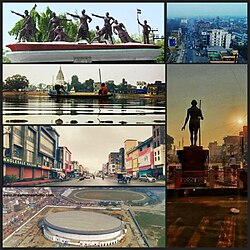

Bettiah

View on WikipediaThis article possibly contains original research. (May 2016) |

Bettiah is a city and the administrative headquarters of West Champaran district (Tirhut Division)[4] in the Indian state of Bihar. It is near the Indo-Nepal border, 225 kilometres (140 mi) northwest of Patna.

Key Information

History

[edit]

In 1244 A.D., Gangeshwar Dev, a Brahmin of the Jaitharia clan, settled at Jaithar in Champaran.[5] One of his descendants, Agar Sen, acquired large territories during the reign of Emperor Jahangir, and was bestowed the title of 'Raja' by Emperor Shah Jahan. In 1659, he was succeeded by his son Raja Gaj Singh, who built the palace of the family at Bettiah. He died in 1694 A.D. The palace stands today and is used as a marketplace.

In 1740, a Roman Catholic mission was founded in the city.[6] On 7 December 1745 AD, Father Joseph Mary, Father Cassen, and Nepali Christian Michael arrived in Bettiah from Nepal. The King of Bettiah provided them with a house located in front of the royal court. This three-room house became the center of their activities. One room served as a clinic where free medicines were distributed to the general public, the second room was a Christian prayer house—a small church, and the third room was dedicated to providing religious education. From this modest setting, the propagation of Christianity began in Bettiah, laying the foundation for what would later become the presence of the Catholic Church in the northern Indian subcontinent, as well as the foundation of the Bettiah Christian community.[7]

In 1765, when the East India Company acquired the Diwani, the Bettiah Raj held the largest amount of territory under its jurisdiction.[8] It consisted of all of Champaran except for a small portion held by the Ram Nagar Raj .[8]

Maharaja Sir Harendra Kishore Singh was the last king of Bettiah Raj.[5] He was born in 1854 and succeeded his father, the late Maharaja Rajendra Kishore Singh Bahadur in 1883. In 1884, he received the title of Maharaja Bahadur as a personal distinction and a Khilat and a sanad from the hands of the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, Sir Augustus Rivers Thompson. He was created a Knight Commander of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire on 1 March 1889. He was appointed a member of the Legislative Council of Bengal in January 1891. He was also a member of The Asiatic Society. He was the last ruler of Bettiah Raj. Maharaja Sir Harendra Kishore Singh Bahadur died heirless on 26 March 1893, leaving behind two widows, Maharani Sheo Ratna Kuer and Maharani Janki Kuer . There are a few institutions named after the queen Maharani Janki Kuer, such as M.J.K College and M.J.K Hospital.

The Bettiah Gharana was one of the oldest styles of vocalised music.[9] Madhuban was part of the erstwhile 'Bettiah Raj'. Internal disputes and family quarrels divided the Bettiah Raj as time went on. As a result, the Madhuban Raj was created.

In 1869, Bettiah was constituted and affirmed as a municipality.

A section of Dhrupad singers of Dilli Gharana (Delhi Gharana) from the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan's court had migrated to Bettiah under the patronage of Bettiah Raj, and thus was sown the seed of Bettiah Gharana.[9] The well-known Dagar brothers had praised the Bettiah Dhrupad singers and some of them were invited to the Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal to perform with other accomplished singers in 1990.[9]

The University of Bihar has a local branch of its college in Bettiah, M.J.K. College, first established in 1955 under the name of Bettiah Mahavidyalya. The current name is in honour of Maharani Janki Kunwar of the Bettiah Raj.[10]

On 26 December 2020, Bettiah became a municipal corporation. It includes Tola San Saraiya, Banuchapar, Kargahiya east and nearby areas. Development and upgrades to the local infrastructure are planned.[1]

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]The climate of Bettiah is characterised by high temperatures and high precipitation especially during the monsoon season. The Köppen Climate Classification sub-type for this climate is "Cwa" (Dry-winter humid subtropical climate).

| Climate data for Bettiah | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

26.3 (79.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

37.3 (99.1) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37 (99) |

33.5 (92.3) |

32.8 (91.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

24.6 (76.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.1) |

18.7 (65.6) |

24.2 (75.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

32 (89) |

32 (89) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.9 (84.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

25.4 (77.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.3) |

11.1 (51.9) |

16.1 (60.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.6 (76.2) |

26.2 (79.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.4 (77.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.6 (58.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

19.2 (66.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13 (0.5) |

13 (0.5) |

10 (0.4) |

18 (0.7) |

46 (1.8) |

200 (7.7) |

380 (14.9) |

360 (14) |

230 (8.9) |

66 (2.6) |

5.1 (0.2) |

5.1 (0.2) |

1,330 (52.4) |

| Average precipitation days | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 5.4 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 45.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 11.1 | 11.7 | 12.4 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 13.5 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 12.6 |

| Source: Weatherbase[11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]As of 2011 Indian Census, Bettiah NP had a total population of 132,209, of which 69,529 were males and 62,680 were females. Population within the age group of 0 to 6 years was 18,995. The total number of literates in Bettiah was 91,298, which constituted 69.1% of the population with male literacy of 72.7% and female literacy of 64.9%. The effective literacy rate of 7+ population of Bettiah was 80.6%, of which male literacy rate was 85.0% and female literacy rate was 75.8%. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes population was 8,266 and 828 respectively. Bettiah had 24,463 households in 2011.[12]

As per 2011 census, the Bettiah Urban Agglomeration had a total population of 156,200, with 82,663 males and 73,537 females. The population within the age group of 0 to 6 years was 22,067, and the effective literacy rate (literacy of people above the age of 7) was 80.89%.[13] The urban agglomeration includes Bettiah (municipal corporation), Tola Mansaraut (census town), Kargahia Purab (census town) and Hat Saraiya (census town).[14]

On 26 December 2020, Bettiah became a municipal corporation. It included Tola San Saraiya, Banuchapar, Kargahiya east, and other nearby areas. The total population at this time was 414,453[1]

Notable landmarks

[edit]- Amwaman Lake- state's first water sports zone[15]

- Sagar Pokhra Bettiah[16]

- Udaypur Wildlife Sanctuary

- Hajarimal Dharmshala- Shyam Baba Mandir

- Mata Ranisati Mandir

- Gopinath Panchayat Mandir

- Sant Ghat Mandir & River Bank

- Joda Shivalay Mandir

- Saraiyaman Jheel

- Shahid Smarak

- Raj Dwedhy- Raj Palace

- Raj Kachhary

- Nazarbagh Park

- Maa Kalibagh Dham

- Durgabagh Mandir

- Christian Quarter Catholic Church

- Jangi Mosque

- Machhli Lok

- Valmiki National Park- a tiger reserve

Transport

[edit]Railway

[edit]

Bettiah is connected to different cities of India through railways. Bettiah railway station is the main railway station serving the city. Direct trains are available to all the major destinations across India like Patna, Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Guwahati, Ahemdabad, Lucknow, Jaipur, Jammu & Katra, etc.

Prajapati Halt railway station, also known as Bettiah Cant Railway station, is another railway station serving the city.

Roadway

[edit]The National Highways 727, 139W, 28B, 727aa, and State Highway 54 pass through the city.

The National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) has declared a new Patna-Bettiah road as National Highway 139W, setting the stage for the construction of a high-quality four-lane road between the two towns that would reduce the distance between them to 167 kilometres from the current 200-odd km, and travel time to around two hours.[17]

The new Gopalganj-Bettiah Road passes through the New Town section of Tola San Saraiyan. Through this new road, a distance of 60 km (37 mi) is shortened from the commute to Gopalganj-Bettiah.[18]

A new expressway is currently being constructed via Bettiah which links Gorakhpur to Siliguri.[19]

A direct NH is being constructed to link Bettiah to Gorakhpur, designated 727aa. NH727AA connects Manuapul (Bettiah), Patzirwa, Paknaha, Pipraghat, and Sevrahi in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.[20]

Airway

[edit]The nearest airport is Kushinagar International Airport which is about 97 km (60 mi) from Bettiah. The nearest airport in Bihar is Jay Prakash Narayan International Airport located in Patna which is about 200 km (120 mi) from Muzaffarpur and 177 km (110 mi) from Areraj.

Education

[edit]Schools

[edit]- Alok Bharati Shikshan Sansthan English Medium School, Bettiah[21]

- Amna Urdu High School, Bettiah[21]

- Oxford Public Boarding & High School, Bettiah[21]

- Assembly of God Church School, Bettiah[21]

- Bipin High School, Bettiah[21]

- Delhi Public School, Bettiah[21]

- Jawahar Navoday Vidyalaya, Vrindavan, Bettiah[22]

- Kendriya Vidyalaya, Bettiah[23]

- Khrist Raja High School, Bettiah[21]

- Kidzee Play School, Bettiah[21]

- Krishna International Public School, Bettiah[21]

- National Public Higher Secondary School, Bettiah[21]

- Notre Dame Public School, Bettiah[21]

- Raj Enter Secondary School, Bettiah[21]

- R.L international School, Bettiah[24]

- S.S. Girls High School, Bettiah[21]

- Sacred Heart High School, Bettiah[21]

- Sarsawati Vidya Mandir, Bettiah[21]

- St. Joseph’s School, Bettiah[21]

- St. Mary/Remijius High School, Bettiah[25]

- St. Michael’s Academy. Bettiah[21]

- St. Teresa's Girls' Senior Secondary School, Bettiah[21]

- St. Xavier's Higher Secondary School, Bettiah[21]

-

St. Xavier's Higher Secondary School

-

St. Joseph's School

-

St. Michael's Academy

-

Khrist Raja High School

-

Assembly of God Church School

Colleges

[edit]- Government Medical College, Bettiah

- Government Engineering College, West Champaran

- Government Polytechnic,West Champaran

- Maharani Janki Kunwar College, Bettiah[26]

- Ram Lakhan Singh Yadav College, Bettiah[26]

- Gulab Memorial College, Bettiah[27]

- MRRG College, Bettiah[28]

- MNM Mahila College, Bettiah

- St. Teresa Primary Teachers Training College, Bettiah[29]

- Chanakya College of Education, Bettiah[30]

- Raj Inter College, Bettiah[31]

-

GMC Academic block

-

Administrative block of Government Engineering College Bettiah, W.Champaran

-

Chanakya College of education

Notable people

[edit]- Manoj Bajpai, Indian film actor

- Prakash Jha, Indian film producer, director, and screenwriter

- Renu Devi, first female and 7th Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar

- Satish Chandra Dubey, politician and Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha

- Sanjay Jaiswal, politician and president of Bharatiya Janata Party, Bihar

- Damodar Raao, Indian film Music Director, Singer, Producer, and Lyrics writer

- Krishna Kumar Mishra, former member of Legislative assembly, Chanpatia (Bihar)

- Vikas Mishra, former Vice-Chancellor, Kurukshetra University

- Gopal Singh Nepali, Hindi poet and Bollywood lyricist

- Gauri Shankar Pandey, former member of Legislative assembly, Bettiah (Bihar)

- Kedar Pandey, 14th Chief Minister of Bihar

- Raj Kumar Shukla, Indian independence activist

The Literary History of Champaran

[edit]Freedom Fighter and author Ramesh Chandra Jha was the first person who penned down the rich literary history of Champaran. His research based books including Champaran Ki Sahitya Sadhana (चम्पारन की साहित्य साधना) (1958), Champaran:Literature & Literary Writers (चम्पारन: साहित्य और साहित्यकार) (1967) and Apne Aur Sapne:A Literary Journey Of Champaran (अपने और सपने: चम्पारन की साहित्य यात्रा) (1988) meticulously document the rich literary heritage and history of Champaran, Bihar. These seminal books continue to serve as foundational reference points for researchers, scholars, Ph.D. students, and journalists alike. Jha's insightful exploration and preservation of Champaran's historical and literary legacy have solidified his place as a cornerstone in the field of literary research.[32]

Art and Culture

[edit]

Kanyaputri Dolls represent a traditional folk craft of Bettiah and the wider West Champaran region, historically made by girls during the monsoon month of Saavan using scraps of cloth. The dolls—often created as sister-brother pairs or as bride-and-groom figures—were associated with rituals celebrating sibling affection and were sometimes sent with newly married women to their sasural as symbols of familial bonds and good fortune.[33] With the spread of mass-produced plastic toys in the late 20th century, this handmade tradition gradually declined and nearly disappeared.[34]

The craft was revived by Bihar State Handicrafts Award Winner Artist and Teacher Namita Azad[35] ,from Manjhariya village in Bettiah, who began recreating the dolls using upcycled fabric and later dedicated herself fully to training local women artisans. Her efforts received organisational and promotional support from Indian Social Entrepreneur Ranjan Mistry[36], helping the initiative expand through exhibitions, state craft platforms, and documentary work highlighting the heritage.[37] The revival has re-established Kanyaputri Dolls as an element of Champaran’s intangible cultural heritage, while also providing sustainable livelihood opportunities for rural women and promoting eco-friendly craft practices.[38] Kanyaputri Doll also recognized as the only State Doll of Bihar.[39]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "पश्चिम चंपारण में बेतिया बना नगर निगम, अब नागरिक सुविधाओं में होगा इजाफा". Dainik Jagran (in Hindi). 26 December 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ a b "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "Bhojpuri". Ethnologue. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Tirhut Division". tirhut-muzaffarpur.bih.nic.in. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- ^ a b Lethbridge, Sir Roper (2005). The Golden Book of India: A Genealogical and Biographical Dictionary of the Ruling Princes, Chiefs, Nobles, and Other Personages, Titled Or Decorated of the Indian Empire. Aakar Books. p. 67. ISBN 978-81-87879-54-1. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ "Bettiah | Bettiah | Town, Temple, Palace | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ पाएं, लिंक (10 January 2021). "History of Bettiah Catholic Church | बेतिया कैथोलिक चर्च का इतिहास" (in Hindi). Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ a b Ram, Bindeshwar (1998). Land and society in India: agrarian relations in colonial North Bihar. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0643-5.

- ^ a b c "Many Bihari artists ignored by SPIC MACAY". The Times of India. 13 October 2001. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "» History | Maharani Janki Kunwar College, Bettiah". www.mjkcollege.ac.in. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase. 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved on 27 August 2015.

- ^ "Census of India: Bettiah". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Urban Agglomerations/Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ "Constituents of urban Agglomerations Having Population 1 Lakh & above" (PDF). Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Amwa Man, the state's first water sports zone, opens for tourists". Dainik Jagran. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "boating started in sagar pokhra of bettiah". Dainik Bhaskar. 1 September 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Pathak, Subhash (9 July 2021). "New Patna-Bettiah NH gets a nod, to cut travel time to 2.5 hours". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Kumar, Arun (14 March 2016). "Need to shun politics for Bihar's growth: Nitish". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "बिहार के लिए खुशखबरी पश्चिम चंपारण होकर गुजरेगा सिलीगुड़ी गोरखपुर एक्सप्रेस हाइवें - Good news for Bihar Siliguri Gorakhpur Express Highway will pass through West Champaran". Jagran (in Hindi). 7 July 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "सड़क प琇रवहनप琇रवहनप琇रवहनप琇रवहन औरऔरऔरऔर राजमाग榁राजमाग榁राजमाग榁राजमाग榁 मं灴ालयमं灴ालयमं灴ालयमं灴ाल" (PDF). Egazette.nic.in. 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Schools". | Official Website of West Champaran | India. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "About JNV". navodaya.gov.in. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "Home| KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA BEIA". Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "R.L International School". Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "www.stremijius.online". Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Public Utilities". Official Website of West Champaran | India. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Mitra, Arnab (16 March 2022). "Bihar Board 12th Result 2022 Updates: BSEB Declares Inter Result; Marksheets At Results.biharboardonline.com". NDTV. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "mrrg college". Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "St. Teresa's Primary Teacher's Education College Bettiah". Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Chanakya College of Education, Bettiah". Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Raj Inter College Bettiah". Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Apne Aur Sapne : Online PDF book at Archive.org

- ^ "Toys of India - Thigma Art". 8 February 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

- ^ Editor (21 January 2022). "Kaniya Putri: An Organic Doll With A Beautiful Message... - E-Journal Times Magazine". journals-times.com. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Namita Azad: Revive the concept of dolls known as Kanyaputri Dolls from Champaran Bihar, Womenia Story, 6 March 2020, retrieved 19 November 2025

- ^ Smita, Juhi; Kumar, Manish; Sinha, Ritika; Kumari, Priti (20 January 2025). Social Entrepreneurs in Bharat. Amazon. ISBN 979-8-3083-0028-1.

- ^ "Sorry for the inconvenience". cgihamburg.gov.in. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

- ^ "GNT Exclusive: Labubu और प्लास्टिक के बीच चंपारण की नमिता आज़ाद ने जिंदा की कन्यापुत्री गुड़िया की परंपरा, बिहार की खोई हुई संस्कृति को दे रहीं वैश्विक पहचान". Good News Today (in Hindi). Retrieved 19 November 2025.

- ^ education.vikaspedia.in https://education.vikaspedia.in/viewcontent/education/childrens-corner/toys-of-india?lgn=en. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

[edit]Bettiah

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient and Medieval Foundations

The Champaran region, encompassing Bettiah in present-day West Champaran district, bears traces of ancient settlement linked to its forested landscape, with the name Champaran evolving from Champaka aranya, denoting a tract of champa (Michelia champaca) forests known in early Indian texts and indicating pre-Mauryan human activity in agrarian and sylvan economies.[5] Archaeological excavations in the district reveal Mauryan-era infrastructure, particularly at Lauriya Nandangarh, approximately 35 kilometers northwest of Bettiah, where a polished sandstone Ashokan pillar—erected around 250 BCE—bears six of Ashoka's major rock edicts inscribed in Brahmi script, advocating ethical governance and non-violence.[6] Adjacent stupas at the site, unearthed in 19th- and 20th-century digs, point to early Buddhist monastic complexes, reflecting the region's incorporation into the Mauryan empire's dhamma propagation networks following Ashoka's Kalinga War conversion circa 261 BCE.[7] These monuments underscore Champaran's strategic position in ancient Bihar's Gangetic plains, where fertile alluvial soils supported rice and pulse cultivation, while proximity to the Siwalik foothills and Nepal border—about 50 kilometers north—likely enabled rudimentary overland exchanges of timber, sal (Shorea robusta) resin, and wild herbs with Himalayan polities, as evidenced by broader Indo-Nepalese trade patterns documented from the 6th century BCE onward.[3] No direct epigraphic or structural evidence confirms urban settlement at Bettiah itself in this era, but the area's continuity as a rural hinterland aligns with Mauryan administrative outposts extending from Pataliputra (modern Patna), approximately 200 kilometers southeast, fostering localized Jain and Buddhist influences amid Vedic agrarian societies.[7] By the medieval period (circa 1200–1700 CE), Champaran transitioned to fragmented polities under regional strongmen amid the decline of Pala and Sena dynasties in Bengal, with local chieftains consolidating agrarian control over villages through land revenue systems predating Mughal formalization.[3] The Bettiah area's indigenous development crystallized in the late 16th to early 17th century, when chieftain Ugra Sen established the proto-Bettiah Raj, a Bhumihar or Rajput-led estate spanning roughly 2,000 square miles of Champaran territory under nominal Mughal suzerainty from Bihar subah, emphasizing fortified villages and tribute collection from rice, sugarcane, and forest yields rather than expansive conquests.[1] This raj's foundations reflected causal adaptations to the Terai's flood-prone ecology and border dynamics, where cross-border raids and timber trade with Nepal hill states supplemented revenue, without reliance on unverified genealogical claims tracing further antiquity.[3]Colonial Era and the Bettiah Raj Estate

The Bettiah Raj originated in the mid-17th century when Raja Ugra Sen established control over the Champaran region as a zamindari under weakening Mughal authority, with his successors consolidating holdings through revenue collection from agricultural lands.[8] Following Raja Dhrub Singh's death in 1762 without a direct male heir, internal succession disputes fragmented the estate temporarily, but British intervention intensified after the East India Company's acquisition of the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1765, placing the Raj—the largest territorial unit under the new revenue jurisdiction—under indirect oversight via enhanced tax assessments and administrative regulations.[8] By the late 18th century, the estate encompassed roughly 2,000 square miles of fertile Champaran territory, yielding annual land revenue exceeding 2 million rupees, primarily from crops like rice and sugarcane, as documented in British revenue records that formalized zamindari rights under the Permanent Settlement of 1793.[3] Key rulers, including Maharaja Jugal Kishore Singh (r. 1762–1783), navigated early British demands, while 19th-century Maharajas such as Harendra Kishore Singh expanded infrastructure, including palace complexes modeled on European designs, amid ongoing negotiations over revenue shares and proprietary claims.[1] Administrative operations relied on a hierarchical structure of zamindars collecting fixed rents from ryots, with British collectors enforcing payments through periodic settlements and auctions for defaults, as evidenced in Champaran land records from the early 1800s that highlight disputes over estate boundaries and assessment rates without peasant uprisings.[3] By 1897, following Maharaja Sheoratan Singh's death in 1896, the British Court of Wards assumed direct management of the estate due to concerns over Maharani Janki Kuar's capacity to handle debts and administration, prioritizing revenue stability and legal oversight until the early 20th century.[3]Indigo Plantations and Agrarian Unrest

British indigo planters began establishing plantations in the Champaran region, encompassing Bettiah, during the late 18th century, capitalizing on the area's alluvial soils and proximity to Bengal's established trade networks for export to European textile markets.[9] By the early 19th century, cultivation expanded under the Permanent Settlement of 1793, which empowered zamindars and European lessees to enforce cash-crop mandates, displacing subsistence farming and integrating ryots into a global commodity chain where indigo fetched high prices abroad—Bengal's output dominated world supplies, with Bihar contributing significantly through Tirhut division factories.[10] [11] This shift prioritized export volumes over local needs, as planters invested capital in factories while ryots faced soil exhaustion from intensive indigo rotations, reducing yields of food grains like rice and wheat essential for regional self-sufficiency.[12] The tinkathia system formalized coercion, requiring ryots to allot 3 kathas per bigha (roughly 3/20 of their tenancy) to indigo under satta contracts—advances disbursed at usurious rates (often 50-100% effective interest via deductions)—locking cultivators into debt traps where repayments exceeded harvest values due to manipulated low procurement prices and penalties for substandard quality.[13] [14] Planters' agents (gomastas) enforced compliance through physical intimidation, eviction threats, and legal manipulation under colonial courts biased toward property rights, fostering a causal chain of impoverishment: diverted acreage spurred food shortages, indebtedness eroded savings, and export booms (Tirhut indigo shipments peaked mid-19th century before synthetic competition) enriched a few hundred European managers while ryot households averaged annual indigo earnings below subsistence levels amid rising rents.[15] [13] Empirical records from magistrate reports indicate no widespread ryot default absent coercion, underscoring systemic extraction over individual non-compliance as the unrest driver.[16] Agrarian resistance emerged episodically from the 1830s, when Tirhut's acting magistrate documented ryot refusals to sow indigo amid debt burdens, escalating to organized protests by the 1860s that echoed Bengal's Blue Mutiny through factory arsons and contract repudiations, though suppressed via military patrols and enhanced policing.[16] [12] Court records from Bihar courts reveal over 100 cases of planter-ryot disputes in Champaran by the 1870s, highlighting clashes over forced deliveries and illegal cesses (abwabs), with ryots leveraging petitions to colonial officials for relief that rarely materialized due to planter lobbying.[15] Tension peaked in 1907-1908 with violent unrest in Bettiah and nearby Sathi estates, where ryots destroyed indigo vats and confronted overseers, protesting tinkathia's rigidity amid falling global prices from German synthetic dyes, which halved export values by 1910 and exposed the system's unsustainability without addressing underlying land alienation.[17] [13] These pre-organized actions, rooted in economic calculus of unviable returns versus planter monopolies, set precedents for collective defiance but remained fragmented, as colonial agrarian laws like the 1885 Bengal Tenancy Act offered nominal occupancy rights insufficient against indigo-specific extortions.[18]Role in the Indian Independence Movement

Raj Kumar Shukla, a prosperous agriculturist from Murali Bharahwa in Champaran, first approached Mahatma Gandhi at the 1916 Lucknow session of the Indian National Congress to highlight the forced indigo cultivation under the tinkathia system imposed on tenants by European planters.[19] Shukla's persistence led Gandhi to visit Champaran, departing Calcutta on April 9, 1917, and arriving in Motihari on April 15, 1917; two inquiry offices were established, one in Bettiah manned by Shukla to collect peasant testimonies.[19][20] In Bettiah, Gandhi based operations from April 22, 1917, at Babu Hazarimal's dharamshala, recording statements from tenants and inspecting villages like Laukaria and Sindhachhapra amid reports of coercion and illegal exactions.[19] Gandhi's on-site investigation defied a district order under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code to leave Champaran, resulting in his court appearance on April 18, 1917, and a brief arrest attempt that was withdrawn after public outcry, establishing a precedent for non-violent resistance against colonial authority.[19] This pressure prompted the British government to appoint the Champaran Agrarian Enquiry Committee on June 13, 1917, including Gandhi as a member, to probe landlord-tenant relations and indigo disputes; sessions convened at Bettiah Raj school from July 17, 1917, examining over 8,000 tenant statements.[19] The committee's report, submitted October 4, 1917, and accepted October 18, 1917, deemed tinkathia coercive and unnecessary for indigo production.[19] The ensuing Champaran Agrarian Act of 1918 abolished tinkathia, voiding contracts mandating indigo on 3 kathas per bigha of tenancy land, reduced sharahbeshi rent enhancements by 20-25 percent, and required planters to refund 25 percent of tawan fines extracted from tenants.[19][21] These reforms freed approximately 2.5 million tenants from indigo obligations, diminishing planter dominance and boosting peasant confidence, with indigo cultivation ceasing district-wide by 1928 and factories sold off.[19] However, deeper tenancy vulnerabilities endured, including abwabs in estates like Ramnagar Raj and unresolved occupancy rights, as the Act preserved underlying zamindari structures without addressing permanent tenure security or full rent rationalization.[19] The Champaran episode galvanized local support for broader nationalism, serving as a model for satyagraha and inspiring participation in subsequent campaigns; echoes appeared in Non-Cooperation Movement activities from 1920, with arrests of regional activists, and intensified during Quit India in 1942, when leaders like Prajapati Mishra in Bettiah faced detention amid strikes and sabotage against colonial infrastructure.[22] Yet, the Satyagraha's immediate agrarian gains did not eradicate systemic exploitation, with peasant unrest recurring until post-1947 zamindari abolition provided lasting redress.[19]Post-Independence Developments

In 1950, the Bihar Land Reforms Act abolished the zamindari system, vesting intermediary interests in land—including those of the Bettiah Raj estate—directly with the state for redistribution to cultivators, aiming to eliminate exploitative rents and enhance tenant security.[23] However, implementation fragmented holdings into uneconomically small parcels, often below viable thresholds for investment or mechanization, as ceilings imposed under the subsequent 1961 Bihar Land Reforms Act limited consolidation and incentivized subdivision among heirs, contributing to stagnant agricultural yields in regions like Champaran where average farm sizes dwindled to under 1 hectare by the 1970s.[24] This causal chain—intermediary removal without complementary credit or extension services—exacerbated productivity shortfalls, as empirical analyses of similar reforms indicate misallocation of land and labor reduced output per unit by distorting scale efficiencies, a pattern evident in Bihar's rice and wheat yields lagging national averages post-reform.[25] Administrative reconfiguration followed in 1972, when the unified Champaran district was divided into East and West Champaran, establishing Bettiah as the headquarters of the western segment to streamline governance over its 5,228 square kilometers and border proximity to Nepal.[1] This bifurcation facilitated localized administration but inherited reform-era disputes, including unresolved claims on Bettiah Raj properties exceeding 15,000 acres, where state acquisition efforts persist amid litigation over titles transferred inadequately in the 1950s.[26] Post-independence censuses document modest urbanization, with Bettiah's municipal population rising from approximately 50,000 in 1951 to over 130,000 by 2011 amid district-wide growth to 3.9 million residents, though urban share remained below 10% due to agrarian dominance and policy neglect of non-farm diversification.[27] Railway infrastructure, anchored by Bettiah station on the Muzaffarpur-Raxaul line, saw incremental electrification and freight enhancements in the late 20th century, yet expansions were constrained by underinvestment, limiting industrial spurs and perpetuating reliance on seasonal migrant labor outflows linked to reform-induced rural stagnation rather than exogenous factors.[28] These dynamics underscore how state interventions, while redistributive in intent, fostered dependency on remittances—evident in West Champaran's high interstate migration rates—by failing to address tenure insecurities that deterred long-term soil improvements or crop intensification.[29]Geography

Location and Topography

Bettiah is located at approximately 26.80°N latitude and 84.50°E longitude in the West Champaran district of Bihar, India.[30] The city sits at an average elevation of 78 meters above sea level, characteristic of the flat Indo-Gangetic Plain.[31] It lies a short distance east of the Gandak River, within its alluvial basin, and approximately 40-50 kilometers south of the Indo-Nepal border, with the district's northern blocks directly adjoining Nepal.[1][32] The topography consists of fertile alluvial plains formed by sediments from the Gandak and other Himalayan rivers, supporting extensive agriculture through rich, moisture-laden soils.[33] These younger alluvial deposits, however, render the area flood-prone, particularly during monsoons when river overflows deposit silt and cause inundation in low-lying zones.[33] The terrain is predominantly level with minimal elevation variations, facilitating settlement patterns centered around trade routes and water access but necessitating embankments and drainage for flood mitigation.[34] West Champaran district, encompassing Bettiah, spans 5,228 square kilometers and is bounded to the north by Nepal, to the south by Gopalganj and East Champaran districts, to the east by East Champaran, and to the west by Uttar Pradesh's Kushinagar district.[1] The urban core of Bettiah aligns with these plains, extending along key transport corridors without significant topographic barriers.[32]Climate Patterns

Bettiah exhibits a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Aw), dominated by seasonal rainfall patterns driven by the southwest monsoon, with hot summers, mild winters, and pronounced dry periods. Average annual precipitation measures approximately 1,472 mm, concentrated primarily between June and September, when the monsoon delivers over 85% of the yearly total, often exceeding 1,200 mm in peak months like July and August.[35] Temperatures fluctuate widely, with summer highs reaching 40°C or more from March to May, winter lows dipping to 7-10°C in December and January, and annual means hovering around 25°C.[31] Data from India Meteorological Department stations in West Champaran district reveal recurrent cycles of excess rainfall leading to flooding—particularly from Himalayan runoff and intensified monsoon depressions—and deficits causing droughts, with variability coefficients exceeding 25% annually. These patterns, evident in records since the early 1900s, show no consistent long-term directional shift in rainfall totals or intensity, but rather oscillations tied to natural phenomena like El Niño-Southern Oscillation influences, contrasting with broader claims of anthropogenic forcing lacking localized causal evidence.[36][37] Such variability directly affects moisture availability for rain-fed crops, including successors to historical indigo like sugarcane, where untimely dry spells or deluges disrupt growth cycles without evidence of novel extremes beyond historical norms.[36]| Season | Average Rainfall (mm) | Temperature Range (°C) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter (Dec-Feb) | 50-100 | 7-25 | Dry, foggy mornings; minimal precipitation |

| Summer (Mar-May) | 100-200 | 25-40+ | Hot, pre-monsoon thunderstorms (locally kal baishakhi) |

| Monsoon (Jun-Sep) | 1,200+ | 25-35 | Heavy, erratic downpours; flood risk |

| Post-Monsoon (Oct-Nov) | 100-150 | 15-30 | Retreating monsoon; occasional cyclones |

Demographics

Population Dynamics and Census Data

According to the 2011 Census of India, Bettiah city recorded a population of 132,209, with 69,529 males and 62,680 females.[2] The sex ratio was 901 females per 1,000 males, below the national urban average of 926.[38] The Bettiah Urban Agglomeration, encompassing adjacent areas, had a total population of 155,518, maintaining the same sex ratio of 901.[38] The city's population grew from 116,670 in the 2001 Census to 132,209 in 2011, reflecting a decadal growth rate of 13.3%.[39] This equates to an average annual growth rate of approximately 1.25%, calculated as the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) using the formula: CAGR = (final value / initial value)^(1/n) - 1, where n=10 years. In the broader Bettiah subdivision, the total population was 224,200, with 66.3% (148,655) residing in urban areas and 33.7% (75,545) in rural areas, indicating moderate urbanization within the locality.[40] West Champaran district, of which Bettiah is the headquarters, had a 2011 population of 3,935,042, with only 9.99% of the district's residents in urban areas, underscoring Bettiah's role as the primary urban center.[41] No official census has been conducted since 2011 due to delays in the 2021 enumeration; unofficial projections for Bettiah's metropolitan area suggest around 214,000 residents by 2023, but these rely on extrapolations from historical trends rather than verified surveys.[38]| Census Year | Bettiah City Population | Decadal Growth Rate (%) | Sex Ratio (Females/1,000 Males) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 116,670 | - | Not specified in available data |

| 2011 | 132,209 | 13.3 | 901 |

Religious, Linguistic, and Socio-Economic Composition

Bettiah exhibits a diverse religious composition, with Hinduism predominant at 64.08% of the population according to the 2011 census, followed by Islam at 33.72%, Christianity at 1.90%, and smaller shares for Sikhs (0.11%), Buddhists (0.01%), and Jains (0.01%).[2] This urban profile reflects a higher proportion of Muslims compared to the surrounding Pashchim Champaran district, where Hindus constitute 77.44% and Muslims 21.98%.[42] The Christian presence, notably around 1.90%, aligns with missionary-influenced communities in the town.[2] Linguistically, Hindi dominates as the primary language spoken by over 70% of residents, serving as the official and administrative medium, while Urdu accounts for about 15-20% of speakers, correlating with the Muslim demographic.[43] Bhojpuri, a regional vernacular, is widely used in informal and rural-adjacent contexts within Bettiah, comprising up to 90% in the broader district alongside Hindi dialects.[44] English proficiency remains limited, primarily among educated urban elites. Socio-economically, Bettiah's population features significant OBC influence, with Yadavs and Kushwahas (Koeris) forming key agrarian and politically active groups amid Bihar's caste-based social structures.[45] Literacy stands at 73.35% for the town, exceeding the district average of 55.70%, though gender disparities persist with male literacy higher than female rates.[2] [42] Poverty affects approximately 30-40% of households, exacerbated by reliance on agriculture and limited industrialization, mirroring Bihar's statewide multidimensional poverty reduction from 51.91% in 2015-16 to around 34% by 2021-22 but remaining elevated in rural peripheries.[46] Scheduled Castes and Tribes represent about 14% and 6% district-wide, influencing lower socio-economic strata through land access and labor patterns.[42]Economy

Agricultural Base and Trade

The agricultural economy of Bettiah, situated in West Champaran district, centers on staple cereals and cash crops, with rice, wheat, maize, and sugarcane dominating production systems. Major cropping patterns include rice-wheat rotations during kharif and rabi seasons, alongside rice-sugarcane combinations that leverage the district's fertile alluvial soils and monsoon-dependent rainfall.[47] Sugarcane serves as a key cash crop, supporting local sugar mills, while maize contributes to both food security and fodder needs.[48] West Champaran ranks prominently in mango production among Bihar districts, yielding fruits for domestic markets due to favorable subtropical conditions.[49] Livestock rearing complements crop farming, with significant populations of buffaloes, goats, and indigenous cattle integral to dairy and meat production. The 2019 Livestock Census recorded approximately 178,085 goats in the district, reflecting a balanced mix of males and females suited to smallholder systems.[50] Buffalo populations, vital for milk output, have supported Bihar's statewide dairy expansion, though district-specific yields remain constrained by feed availability and veterinary access.[51] Bettiah functions as a regional trade hub through weekly markets and proximity to the Nepal border, facilitating exports of perishables like vegetables, fruits, and grains via informal cross-border channels. Border points near Bettiah, such as those in Lauria and Thakraha, handle substantial volumes of agricultural commodities, with disruptions from Nepal unrest in 2025 causing daily losses exceeding ₹200 crore in Bihar's frontier trade.[52] Informal networks exploit porous borders for commodities like fertilizers and produce, driven by price differentials, though this evades formal tariffs and contributes to smuggling risks.[53][54] Crop yields in the region experienced limited gains post-Green Revolution compared to northwest India, attributable to irregular irrigation coverage—historically below 50% in Bihar—and flood-prone topography in Champaran. Pre-1960s paddy yields averaged under 1,000 kg/ha without high-yielding varieties (HYVs), rising modestly to 2,000-3,000 kg/ha by the 2020s through partial HYV adoption and canal expansions like the Gandak project, yet causal factors such as soil erosion and input inefficiencies persist.[55] Wheat productivity followed suit, constrained by similar hydrological challenges rather than seed technology alone.[56] Irrigation deficits, covering only sporadic areas via wells and rivers, underscore ongoing causal barriers to scaling output despite varietal improvements.[57]Industrial Activities

Bettiah hosts a modest industrial base dominated by small-scale and cottage manufacturing, with the district's three industrial areas including one in Bettiah spanning 29.48 hectares.[58] Registered micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in West Champaran number 1,835, generating approximately 7,846 jobs in small-scale units alone, supplemented by 450 positions in the four large and six medium enterprises.[58] These activities contribute a minor share to the local economy, overshadowed by agriculture, with manufacturing focused on low-capital, labor-intensive operations rather than heavy industry. A notable cottage industry cluster in the Bettiah area produces brass and German silver utensils, comprising 28 functional units that employ 1,025 workers and generate annual turnover of ₹10 lakh, primarily for domestic markets.[58] Other small-scale manufacturing includes metal-based fabrication such as steel works, wood and furniture production (260 units), and limited cotton and jute textile processing, reflecting adaptation from the region's historical indigo cultivation and processing, which declined sharply after the introduction of synthetic dyes in the early 20th century.[58] Large units remain scarce, limited to four entities like the Bihar Seed Corporation in the Bettiah industrial area, constrained by inadequate power supply and infrastructure development.[58][59] Export-oriented production is negligible, with no major industrial exports recorded to neighboring Nepal despite the district's proximity to the border.[58] Recent initiatives, such as the 2024 approval for a multi-sector Special Economic Zone in nearby Kumarbagh, aim to bolster manufacturing prospects, but current activities emphasize localized, artisanal outputs over scaled operations.[60]Economic Challenges and Government Interventions

Bettiah faces persistent economic hurdles rooted in structural factors, including an unemployment rate mirroring Bihar's elevated levels, estimated at around 14% statewide as of 2025, with youth unemployment ranking ninth nationally and only 8.5% of the workforce in salaried jobs.[61][62] This contributes to high outmigration and underutilized labor, particularly in West Champaran, where fragmented landholdings and low skill development exacerbate dependency on agriculture vulnerable to seasonal disruptions. Recurrent floods from rivers like the Gandak inflict substantial damages, eroding agricultural productivity and infrastructure, with Bihar-wide flood losses hindering overall economic momentum by disrupting supply chains and causing asset destruction estimated in billions annually across the state.[63] Land encroachments, affecting over 50% of historical estates in the region, further constrain viable land for industrial or commercial expansion, limiting investment and perpetuating low productivity in key sectors.[64] Government responses have included targeted infrastructure projects to alleviate congestion and spur activity. In May 2025, the Bihar government approved a ₹19.32 crore, 2.36 km bypass road in Bettiah to reduce traffic bottlenecks, incorporating a 1.69 km main stretch and a 0.67 km link road, aimed at enhancing connectivity for trade and mobility.[65] Similarly, reconstruction of the Maharaja Stadium was announced in December 2024, with tenders floated by May 2025 at ₹50.50 crore to create a modern facility capable of hosting state-level events, potentially boosting local sports-related employment and tourism.[66][67] Broader initiatives encompass the Chanpatia startup zone near Bettiah, launched in 2020 to employ returnee migrants with over 57 units and ₹15 crore in sales initially, but by 2025, it has faltered due to inadequate sustained support, market access issues, and operational challenges, highlighting limited long-term efficacy in fostering self-sustaining industries.[68] These interventions reflect a policy tilt toward subsidies and grants, which critics argue entrenches dependency by prioritizing short-term relief over structural reforms like skill enhancement and market-driven incentives, as evidenced by Bihar's cycle of low per capita income sustaining demand for fiscal support equivalent to half its growth budget in sectors like power.[69][70] Empirical data on similar programs indicate mixed outcomes, with initial job creation in zones like Chanpatia not translating to scalable growth absent private investment and reduced reliance on state aid, underscoring the need for causal focus on enabling competitive markets over perpetual interventions.[71]Governance and Administration

Local Government Structure

Bettiah's urban local governance is managed by the Bettiah Nagar Nigam, a municipal corporation upgraded from nagar parishad status in December 2020 under Bihar state legislation, originally established in 1889 to administer civic affairs over an area of 11.63 square kilometers divided into 46 electoral wards.[72][28] The corporation's structure follows the Bihar Municipal Act, 2007, featuring an elected municipal council with a mayor as chairperson, ward councilors, empowered standing committees for specialized oversight, and an executive wing led by a municipal commissioner responsible for day-to-day operations including property tax collection, building permissions, and trade licensing.[73][74] Key functions encompass public health and sanitation, such as waste management and drainage maintenance; water supply and sewerage systems; urban road upkeep and street lighting; and preventive measures against fire hazards and contagious diseases, with internal audits periodically assessing compliance and financial accountability in these areas.[73][75] Overarching district administration for West Champaran, with headquarters in Bettiah, centers on the district collectorate headed by the District Magistrate, who coordinates revenue divisions through three sub-divisions—Bettiah, Bagaha, and Narkatiyaganj—and supervises 18 development blocks encompassing rural governance via gram panchayats for village-level planning and resource allocation across 1,507 revenue villages.[76][77][58]Political Representation and Dynamics

Bettiah falls under the Paschim Champaran Lok Sabha constituency, represented since 2014 by Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) MP Dr. Sanjay Jaiswal, who secured re-election in June 2024 with 603,706 votes against Indian National Congress (INC) candidate Madan Mohan Tiwari's 466,127 votes, achieving a margin of 137,579 votes.[78][79][80] The Bettiah Assembly constituency, one of seven within Paschim Champaran, is held by BJP MLA Renu Devi, elected in November 2020 with 84,496 votes (52.83% share), defeating INC's Tiwari by 18,079 votes in a contest marked by high turnout of approximately 62%.[81][82] Electoral dynamics in Bettiah reflect broader Bihar patterns, where voting alignments often align with caste identities, including upper castes and Scheduled Castes favoring BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) coalitions, while Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) draws Yadav and Muslim support.[83] Historically dominated by Congress until the 1990s, the area saw shifts toward RJD during Lalu Prasad Yadav's era amid Mandal-era caste mobilization, but NDA regained ground post-2005 with BJP-JDU governance emphasizing development over identity politics.[84] In Paschim Champaran, BJP has held the Lok Sabha seat consecutively since 2014, with 2020 assembly results showing NDA capturing five of seven seats, including Bettiah, underscoring a decade-long hold amid alliance volatility like Nitish Kumar's 2022 NDA rejoining.[85] Corruption allegations persist, exemplified by the May 2025 arrest of Bettiah District Education Officer Rajnikanth Praveen under the Prevention of Corruption Act for bribery and criminal misconduct involving disproportionate assets.[86] An August 2025 incident involved suspension of West Champaran revenue staff after a video of bribe-taking surfaced, highlighting ongoing administrative graft despite NDA anti-corruption drives.[87] As Bihar approaches 2025 assembly polls, NDA's incumbency faces challenges from INDIA bloc resurgence, with caste arithmetic poised to influence outcomes in upper-caste leaning Bettiah.[88]Bettiah Raj Properties Dispute and Land Encroachments

The Bihar Legislative Assembly passed the Vesting of Bettiah Raj Properties Bill, 2024, on November 26, 2024, enabling the state government to acquire approximately 15,215 acres of land historically associated with the erstwhile Bettiah Raj estate in West Champaran district.[89][90] The legislation, notified via gazette on December 11, 2024, vests these properties directly in the state, overriding prior claims and authorizing the removal of encroachments, including permanent structures, to facilitate public development projects such as infrastructure and welfare initiatives.[91][92] Officials estimated the land's market value at around ₹8,000 crore, with significant portions—up to 66% or roughly 6,505 acres—reportedly encroached upon through unauthorized occupations that proliferated due to lax post-abolition enforcement following the Bihar Land Reforms Act of 1950.[93][94] Proponents within the government argued that the vesting addresses decades of mismanagement under the Court of Wards, where illegal settlements and forged revenue records undermined potential public utility, positioning the takeover as a means to reclaim assets for equitable development amid Bihar's infrastructure deficits.[95][96] The Revenue and Land Reforms Department planned to verify occupants' documents post-enactment, emphasizing that genuine long-term lessees or allottees would receive fair consideration, though critics highlighted risks of arbitrary evictions without robust adjudication.[97] This approach reflects a causal pattern in post-independence land governance, where abolition of zamindari systems without effective state stewardship enabled widespread informal appropriations, potentially justifying state intervention for broader welfare but raising concerns over compensatory adequacy and selective enforcement. Heir claimants to the Bettiah Raj estate, referencing Supreme Court rulings such as State of Bihar v. Radha Devi that had previously adjudicated inheritance disputes, formally opposed the bill by petitioning Bihar Governor Rajendra Arlekar on December 9, 2024, urging withholding of assent on grounds that it unlawfully extinguishes vested private rights without due process or compensation equivalent to the properties' historical and economic value.[98][91] They contended that the estate's remnants, preserved under Court of Wards oversight after zamindari abolition, represented legitimate successor interests, and that the state's development rationale masked overreach, potentially prioritizing political expediency over property protections enshrined in Article 300A of the Indian Constitution.[99] Despite these objections, the governor assented, formalizing the transfer and empowering district collectors to execute clearances, though implementation challenges persist, including interstate claims extending to areas like Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh. The dispute underscores tensions between public infrastructure imperatives and individual property safeguards, with empirical evidence of encroachments supporting reclamation needs while historical mismanagement implicates state accountability in prior failures to curb illegal occupations.[100]Culture and Society

Religious Practices and Festivals

Bettiah's religious landscape features Hindu-majority practices centered on festivals like Chhath Puja, observed annually in October or November with devotees fasting for 36 hours and offering prayers to the rising and setting sun at ghats such as Sant Ghat, attracting thousands for rituals including thekua offerings and holy dips. Diwali involves lighting diyas and fireworks, while Durga Puja features idol immersions and pandal visits, reflecting seasonal agricultural cycles and community gatherings. These events, tied to ancient Vedic traditions, emphasize empirical devotion through prolonged exposure to natural elements, though participation rates vary by caste and rural-urban divides, with urban Bettiah seeing organized ghats prepared by municipal authorities.[101] Muslim communities mark Eid-ul-Fitr and Eid-ul-Adha with prayers at mosques like Jangi Masjid, followed by feasts and charity, aligning with lunar calendar observances that coincide sporadically with Hindu events, occasionally heightening local sensitivities over processions. The historic Bettiah Christian community, tracing to Capuchin missions established in 1740, celebrates Christmas with midnight masses and Easter processions, alongside diocesan events like the annual Bible Festival involving youth dramatizations and dances to reinforce scriptural knowledge. These minority practices, numbering around 5-10% of the population based on district demographics, maintain distinct liturgical calendars without widespread syncretic fusion, often limited to pragmatic civic accommodations during shared public spaces.[102] Annual temple fairs at sites like Sagar Pokhra Shiv Mandir and Joda Shivalaya draw pilgrims for Shiva worship during Maha Shivratri, featuring bhajans, Prasad distribution, and temporary melas with over 10,000 attendees, as evidenced by local records of Bettiah Raj patronage constructing 56 such temples with Suryadev idols. Kali temples host similar Navratri observances with animal sacrifices in some rural extensions, underscoring ritualistic causality in warding perceived misfortunes. However, interfaith dynamics reveal tensions, as in the August 9, 2013, Nag Panchami procession where provocative messages incited Hindu-Muslim stone-pelting, arson of official vehicles, and a curfew, resulting in injuries and arrests, highlighting how religious processions can escalate underlying land or political disputes rather than foster cohesion. Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar attributed such incidents to deliberate misuse of fetes for communal provocation, with data showing a tripling of clashes post-2013 political shifts, underscoring empirical risks over idealized harmony narratives.[103][104][105]Literary History of Champaran

The exploitation of indigo cultivation in Champaran drew early attention in colonial administrative records, with the first documented peasant disturbance occurring in 1867, as planters enforced the tinkathia system requiring farmers to devote 3/20th of their land to indigo.[106] British reports from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including those on agrarian relations, detailed the coercive practices but often framed them within economic imperatives of the indigo trade, which peaked under European planters until synthetic dyes reduced demand post-1910.[9] These documents, such as district gazetteers and revenue surveys, provided empirical data on yields and rents but rarely critiqued the systemic abuses, reflecting the colonial government's alignment with planter interests.[13] Mahatma Gandhi's 1917 intervention marked a pivotal shift, as he compiled over 8,000 peasant testimonies in vernacular languages, including Bhojpuri, exposing illegal abwabs (extractions) and physical coercion by planters.[107] His report to the Champaran Agrarian Enquiry Committee, submitted in 1917, advocated abolishing the tinkathia system based on direct evidence from ryots, leading to the committee's recommendations for rent reductions and voluntary indigo planting.[108] Gandhi later recounted the events in The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1927-1929), portraying Champaran as the genesis of large-scale satyagraha in India, with the writings circulating through pamphlets and newspapers to rally support.[109] Rajendra Prasad's Satyagraha in Champaran (1928), drawing on eyewitness accounts, further documented the campaign's tactics and outcomes, emphasizing non-violent resistance against entrenched planter power.[19] Post-independence, 20th-century Hindi and Bhojpuri literature reflected on the satyagraha's legacy, with journalistic pieces like those by Pir Muhammad Munis in the 1910s highlighting peasant plight through serialized reports in Urdu-Hindi presses.[110] Bhojpuri oral traditions and translated testimonies preserved local narratives of indigo resistance, though their circulation remained regional until anthologized in works like the 2017 collection of 165 peasant statements.[107] Modern publications, such as Gandhi and the Champaran Satyagraha: Select Readings (2022), compile contemporary reflections but show limited causal influence beyond reinforcing Gandhian historiography, as evidenced by their academic rather than mass dissemination.[111] The writings' impact on nationalism was confined to inspiring satyagraha's replication in other regions, substantiated by Gandhi's own application in Kheda (1918), rather than widespread literary emulation in Champaran-specific folk forms.[112]Education

Schools and Primary Education

Primary education in Bettiah, part of West Champaran district, relies on a mix of government-run and private institutions, with the district featuring 1,340 government primary schools serving foundational learning for children aged 6-10.[1] Enrollment in primary and upper primary levels across the district reached significant numbers by 2019-2020, though precise Bettiah-specific figures highlight urban concentration amid broader rural shortages.[113] The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), initiated in 2001 as India's flagship program for universal elementary education, has boosted access through infrastructure upgrades like additional classrooms and toilets in West Champaran schools, though quality improvements lag due to persistent teacher absenteeism and learning outcomes.[114] Post-2000s literacy drives under SSA increased gross enrollment ratios toward 95-98% for ages 6-14 in Bihar, but rural Bettiah areas show uneven implementation with gaps in functional facilities.[115] Dropout rates at the primary level in Bihar stand at approximately 9.06%, with West Champaran mirroring this trend around 10% based on 2021-2022 district data, often linked to economic pressures and inadequate rural infrastructure.[116][117] Surveys from the 2020s, including ASER reports, indicate student attendance below 60% in primary grades district-wide, underscoring retention challenges despite SSA interventions.[118] Christian missionary institutions have historically advanced primary education in Bettiah since 1816, when schools for converts were established, predating widespread government efforts and emphasizing English-medium instruction in places like St. Xavier's Higher Secondary School (founded 1998) and Khrist Raja High School.[119] These private entities, including St. Joseph's and St. Michael's Academy, continue to supplement government schools by offering better facilities in urban pockets, though rural access remains limited by distance and poverty.[120] Infrastructure disparities persist, with 2020s UDISE+ data revealing incomplete electrification and sanitation in many rural primaries, hindering equitable foundational learning.[121]Colleges and Higher Education Institutions

Higher education in Bettiah primarily consists of colleges affiliated with Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar Bihar University (BRABU) for arts, science, and commerce programs, alongside specialized government institutions for medical and engineering fields. Key undergraduate colleges include Maharani Janki Kunwar College and Ram Lakhan Singh Yadav College, both constituent units of BRABU offering degrees in humanities, sciences, and vocational subjects aligned with regional needs such as agriculture-related courses.[122][123] The Government Medical College, Bettiah, established with Letter of Permission in 2013 by the Medical Council of India (now National Medical Commission), admits 120 students annually for MBBS through NEET-UG, focusing on medical education and healthcare training attached to the historic Maharani Janki Kunwar Hospital.[124][125] The Government Engineering College, West Champaran, founded in 2019 under the Bihar government's "Saat Nischaya" initiative, provides B.Tech programs in branches like civil, mechanical, and computer science engineering, approved by AICTE and affiliated with Bihar Engineering University to address technical skill gaps and reduce youth out-migration for higher studies.[126][127] Quality assessments vary; Ram Lakhan Singh Yadav College holds NAAC accreditation from its first cycle evaluation, indicating basic standards in infrastructure and academics, while newer institutions like the engineering college emphasize expansion to meet demand amid Bihar's low gross enrollment ratio in higher education.[128] These facilities support vocational training in agriculture and technology, though challenges persist with faculty shortages and infrastructure needs to retain local talent.[129]Infrastructure

Transport Networks

Bettiah is linked to the national road network primarily through National Highway 727, which connects the city to Bagaha in the west and integrates with broader corridors like NH-139W for access to northern Bihar districts.[130] This highway facilitates vehicular traffic, including goods transport towards Uttar Pradesh and Nepal border points, though specific usage volumes remain undocumented in public records. Auxiliary routes such as NH-727AA extend from Bettiah towards Sevrahi in Uttar Pradesh, spanning 39 km and supporting regional connectivity.[131] The Bettiah railway station serves as a key junction on the Muzaffarpur–Gorakhpur main line, enabling passenger and freight movement across Bihar and into Uttar Pradesh.[132] The network benefits from Bihar's complete railway electrification achieved by 2025, improving operational efficiency with electric traction across the state.[133] Station redevelopment under the Amrit Bharat scheme, costing approximately ₹54 crore, enhances amenities but focuses on existing infrastructure rather than expanding lines.[134] Bus services provide intra-state and inter-state connectivity, with multiple daily departures from Bettiah to Patna covering 202 km in about 3 hours 40 minutes via operators including Bihar State Road Transport Corporation (BSRTC) and private firms.[135] Routes to Delhi operate with fares ranging from ₹1,599 to ₹3,000, accommodating long-distance travel demands.[136] Proximity to the Nepal border leverages road links for informal trade, though formalized bus services to Nepal are limited, relying instead on rail and highway extensions for cross-border logistics.[130]Urban Development Projects

The reconstruction of Maharaja Stadium in Bettiah, announced by Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar on December 23, 2024, aims to upgrade the facility to host state and national-level sports events, replacing the existing dilapidated structure at an estimated cost exceeding ₹50.50 crore under an EPC mode tender floated by the Bihar State Building Construction Corporation Limited in May 2025.[67][66] As of late 2025, the project remains in the tendering phase with no reported completion timeline, funded through state sports infrastructure allocations.[137] In May 2025, the Bihar government sanctioned ₹19.32 crore for a 2.36 km bypass road in Bettiah to mitigate chronic traffic congestion in the city center, with construction directed to commence promptly under state road development funds.[65] This initiative, reiterated by the Chief Minister during a December 2024 review of West Champaran projects, targets improved urban mobility without specified completion dates as of October 2025.[138] Expansion of the Chanpatia industrial area, a startup zone established post-2020 for migrant returnees with 57 operational units generating over ₹15 crore in sales, was proposed by the Chief Minister in December 2024 to accommodate additional manufacturing sheds and boost local employment under the Bihar Industrial Area Development Authority.[139][138] Despite initial successes, the zone has faced operational challenges including lease disputes and declining unit activity by mid-2025, with expansion plans lacking detailed funding or timelines beyond state industrial budgets.[68] The National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), in partnership with Bihar's Board of Revenue, initiated a two-phased integrated master plan in July 2025 for the strategic development and optimal utilization of Bettiah Raj lands, encompassing historic estate properties to foster coordinated urban growth including potential commercial and residential zones.[140] This effort, funded via state collaboration without disclosed specific budgets, involves GIS mapping and brainstorming sessions but remains in the planning stage as of October 2025, prioritizing evidence-based land use over prior encroachments.[141]Landmarks and Heritage

Religious and Temple Sites

Bettiah features several historic temples constructed under the patronage of the Bettiah Raj, reflecting the region's Hindu devotional traditions. These sites include shrines dedicated to deities such as Kali, Durga, and Shiva, with structures originating from the 17th to 19th centuries. The temples served as centers of worship and were integral to local royal legacy, often featuring idols of Suryadev alongside primary deities.[142] The Kali Bagh Mandir, also known as Kaalibagh Temple, stands as one of the oldest religious sites, constructed around 1614 AD by the royal family of Bettiah. Located near the Bettiah Palace, it witnessed significant historical events, including the Champaran Satyagraha led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1917. Dedicated to Goddess Kali, the temple complex spans approximately 13 acres, including a central pond, and remains an active place of worship.[143][144] Durga Bagh Mandir, situated in Hathikhana, is dedicated to Maa Durga and was built by Maharaja Harendra Kishore Singh of Bettiah Raj in the 19th century. This temple exemplifies the architectural patronage of the era, serving as a focal point for devotees.[145][146] The Sagar Pokhra Shiv Mandir, associated with the ancient Sagar Pokhara pond excavated by Maharani Janki Kunwar, honors Lord Shiva, locally revered as Manokamna Mahadev. Constructed by Maharaja Harendra Kishore, the temple draws worshippers to its serene pondside location, emphasizing its role in ongoing Shiva veneration.[147][148] Other notable temples include the ancient Nara Devi Temple and Gauri Shankar Temple, both preserved from earlier periods under Bettiah Raj influence, alongside Shiva-Parvati shrines mentioned in district records. These sites collectively represent over 50 temples erected by the Maharajas, underscoring the dynasty's contributions to religious infrastructure.[5][149][142]Historical Structures and Monuments

The remnants of the Bettiah Raj Palace, constructed as the headquarters of a prominent 17th-century zamindari estate spanning about 2,000 square miles, stand as a primary non-religious historical edifice in Bettiah.[150] These structures, including the Ghanta Ghar clock tower, reflect the architectural legacy of the estate's rulers, who traced their lineage to Mughal-era grants.[151] Currently, the palace properties face significant encroachment, with surveys indicating that roughly half of the associated 15,000 acres of Bettiah Raj land has been illegally occupied, prompting state government intervention through the Vesting of Bettiah Raj Properties Act, 2024, to facilitate removal and potential restoration.[93][152] Approximately 22-28 kilometers northwest of Bettiah lies the Lauriya Nandangarh site, featuring a well-preserved Ashokan pillar from the Mauryan era, erected around the 3rd century BCE to propagate edicts of Emperor Ashoka.[153] This monolithic polished sandstone column, standing over 10 meters tall with a single lion capital, marks one of the few surviving examples of Ashokan monumental architecture in the region, underscoring the area's archaeological ties to early imperial administration and Buddhist propagation without overt religious iconography.[154] Excavations at the site have uncovered additional Mauryan artifacts, highlighting its significance for understanding ancient urban and infrastructural development in Champaran.[5] Preservation efforts for these monuments are challenged by ongoing encroachments on surrounding lands and environmental threats, such as periodic flooding that has submerged parts of the Ashokan pillar, as documented in 2021 reports.[155] The Bihar government's recent acquisition of Bettiah Raj assets aims to address mismanagement and enable heritage development plans, potentially enhancing tourism by safeguarding these sites from further degradation.[26] Despite their historical value, limited infrastructure has curtailed visitor access, though the pillars' proximity to Bettiah positions the area for expanded archaeological tourism if restoration proceeds.[152]Notable Individuals

Historical Figures

Maharaja Gaj Singh, who ruled in the late 17th to early 18th century, consolidated the Bettiah Raj as a significant zamindari estate under Mughal suzerainty, receiving the title of Raja from Emperor Shah Jahan and expanding agricultural domains including indigo cultivation that bolstered regional economy but later fueled tenant discontent.[3][150] His administration maintained feudal structures emphasizing land revenue collection, which, while stabilizing local governance, entrenched hierarchical land relations prone to exploitation amid fluctuating crop demands.[150] Maharaja Sir Harendra Kishore Singh (1854–1893), the last independent ruler of Bettiah Raj, succeeded in 1883 and focused on modernization efforts, including patronage of Western education through support for institutions like St. Xavier's School and the establishment of the Maharaja Harendra Kishore Public Library in Bettiah, reflecting an attempt to blend traditional authority with progressive reforms.[151][150] Despite these initiatives, his reign occurred amid growing British oversight via the Court of Wards post his death, underscoring the inefficiencies of the zamindari system, which relied on absentee landlords and rigid tenancy laws that exacerbated agrarian tensions without adaptive economic diversification.[3] Raj Kumar Shukla (1875–1929), an indigo cultivator from the Champaran region encompassing Bettiah, emerged as a pivotal resister against planter exploitation by persistently lobbying Mahatma Gandhi at the 1916 Lucknow Congress session to investigate tenant abuses, culminating in the 1917 Champaran Satyagraha that exposed coercive indigo contracts and prompted legal inquiries into estate practices.[156][157] Shukla's grassroots advocacy highlighted systemic flaws in the Bettiah Raj's administrative model, where revenue imperatives often prioritized export crops over ryot welfare, leading to widespread peasant mobilization and partial relief through the Champaran Agrarian Act of 1918.[158]Contemporary Personalities

Manoj Bajpayee, born on April 23, 1969, in Belwa village near Bettiah in West Champaran district, Bihar, is an acclaimed Indian actor known for his versatile roles in Hindi cinema.[159] He gained prominence with his National Film Award-winning performance as Bhiku Mhatre in Satya (1998) and has since starred in critically praised films such as Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) and Aligarh (2015), earning multiple Filmfare Awards for his portrayals of complex characters often rooted in rural Indian settings.[160] Bajpayee's work extends to web series like The Family Man (2019–present), where he plays a intelligence officer, reflecting his commitment to narratives addressing social and political issues.[161] Prakash Jha, born on February 27, 1952, in Barharwa near Bettiah, West Champaran, Bihar, is a prominent film director, producer, and screenwriter specializing in political and social dramas.[162] He debuted with Hip Hip Hurray (1984) and achieved commercial success with films like Gangajal (2003), which critiqued corruption in policing, followed by Raajneeti (2010) and Aarakshan (2011) that explored electoral politics and reservation policies, respectively.[163] Jha's production house has backed over 20 feature films, often drawing from Bihar's socio-political landscape, and he continues to direct series such as Aashram (2020–present) addressing themes of power and exploitation.[164] Renu Devi, born on November 1, 1959, and representing Bettiah as a Bharatiya Janata Party legislator since 2000, served as Bihar's first female Deputy Chief Minister from November 2020 to August 2022.[165] A four-time Member of the Legislative Assembly from the Bettiah constituency, she has held ministerial portfolios including Backward Classes and Disability Welfare, focusing on welfare schemes for marginalized groups in West Champaran.[166] Devi's political rise from an insurance agent to a senior BJP leader underscores her advocacy for women's empowerment and rural development in the region.[167]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shiv_Temple%2C_Bettiah.jpg