Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Circadian rhythm

View on Wikipedia

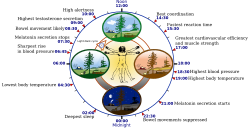

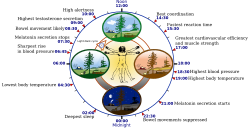

| Circadian rhythm | |

|---|---|

Features of the human circadian biological clock based on a person who goes to sleep at 10 PM | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Frequency | Repeats roughly every 24 hours |

A circadian rhythm (/sərˈkeɪdiən/), or circadian cycle, is a natural oscillation that repeats roughly every 24 hours. Circadian rhythms can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., endogenous) and responds to the environment (is entrained by the environment). Circadian rhythms are regulated by a circadian clock whose primary function is to rhythmically co-ordinate biological processes so they occur at the correct time to maximize the fitness of an individual. Circadian rhythms have been widely observed in animals, plants, fungi and cyanobacteria and there is evidence that they evolved independently in each of these kingdoms of life.[1][2]

The term circadian comes from the Latin circa, meaning "around", and dies, meaning "day". Processes with 24-hour cycles are more generally called diurnal rhythms; diurnal rhythms should not be called circadian rhythms unless they can be confirmed as endogenous, and not environmental.[3]

Although circadian rhythms are endogenous, they are adjusted to the local environment by external cues called zeitgebers (from German Zeitgeber (German: [ˈtsaɪtˌɡeːbɐ]; lit. 'time giver')), which include light, temperature and redox cycles. In clinical settings, an abnormal circadian rhythm in humans is known as a circadian rhythm sleep disorder.[4]

History

[edit]The earliest recorded account of a circadian process is credited to Theophrastus, dating from the 4th century BC, probably provided to him by report of Androsthenes, a ship's captain serving under Alexander the Great. In his book, 'Περὶ φυτῶν ἱστορία', or 'Enquiry into plants', Theophrastus describes a "tree with many leaves like the rose, and that this closes at night, but opens at sunrise, and by noon is completely unfolded; and at evening again it closes by degrees and remains shut at night, and the natives say that it goes to sleep."[5] The mentioned tree was much later identified as the tamarind tree by the botanist H. Bretzl, in his book on the botanical findings of the Alexandrian campaigns.[6]

The observation of a circadian or diurnal process in humans is mentioned in Chinese medical texts dated to around the 13th century, including the Noon and Midnight Manual and the Mnemonic Rhyme to Aid in the Selection of Acu-points According to the Diurnal Cycle, the Day of the Month and the Season of the Year.[7]

In 1729, French scientist Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan conducted the first experiment designed to distinguish an endogenous clock from responses to daily stimuli. He noted that 24-hour patterns in the movement of the leaves of the plant Mimosa pudica persisted, even when the plants were kept in constant darkness.[8][9]

In 1896, Patrick and Gilbert observed that during a prolonged period of sleep deprivation, sleepiness increases and decreases with a period of approximately 24 hours.[10] In 1918, J. S. Szymanski showed that animals are capable of maintaining 24-hour activity patterns in the absence of external cues such as light and changes in temperature.[11]

In the early 20th century, circadian rhythms were noticed in the rhythmic feeding times of bees. Auguste Forel, Ingeborg Beling, and Oskar Wahl conducted numerous experiments to determine whether this rhythm was attributable to an endogenous clock.[12] The existence of circadian rhythm was independently discovered in fruit flies in 1935 by two German zoologists, Hans Kalmus and Erwin Bünning.[13][14]

In 1954, an important experiment reported by Colin Pittendrigh demonstrated that eclosion (the process of pupa turning into adult) in Drosophila pseudoobscura was a circadian behaviour. He demonstrated that while temperature played a vital role in eclosion rhythm, the period of eclosion was delayed but not stopped when temperature was decreased.[15][14]

The term circadian was coined by Franz Halberg in 1959.[16] According to Halberg's original definition:

The term "circadian" was derived from circa (about) and dies (day); it may serve to imply that certain physiologic periods are close to 24 hours, if not exactly that length. Herein, "circadian" might be applied to all "24-hour" rhythms, whether or not their periods, individually or on the average, are different from 24 hours, longer or shorter, by a few minutes or hours.[17][18]

In 1977, the International Committee on Nomenclature of the International Society for Chronobiology formally adopted the definition:

Circadian: relating to biologic variations or rhythms with a frequency of 1 cycle in 24 ± 4 h; circa (about, approximately) and dies (day or 24 h). Note: term describes rhythms with an about 24-h cycle length, whether they are frequency-synchronized with (acceptable) or are desynchronized or free-running from the local environmental time scale, with periods of slightly yet consistently different from 24-h.[19]

Ron Konopka and Seymour Benzer identified the first clock mutation in Drosophila in 1971, naming the gene "period" (per) gene, the first discovered genetic determinant of behavioral rhythmicity.[20] The per gene was isolated in 1984 by two teams of researchers. Konopka, Jeffrey Hall, Michael Roshbash, and their team showed that the per locus is the centre of the circadian rhythm, and that loss of per stops circadian activity.[21][22] At the same time, Michael W. Young's team reported similar effects of per, and that the gene covers 7.1-kilobase (kb) interval on the X chromosome and encodes a 4.5-kb poly(A)+ RNA.[23][24] They went on to discover the key genes and neurones in Drosophila circadian system, for which Hall, Rosbash, and Young received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017.[25]

Joseph Takahashi discovered the first mammalian circadian clock mutation (clockΔ19) using mice in 1994.[26][27] However, recent studies show that deletion of clock does not lead to a behavioral phenotype (the animals still have normal circadian rhythms), which questions its importance in rhythm generation.[28][29]

The first human clock mutation was identified in an extended Utah family by Chris Jones, and genetically characterized by Ying-Hui Fu and Louis Ptacek. Affected individuals are extreme 'morning larks' with 4-hour advanced sleep and other rhythms. This form of familial advanced sleep phase syndrome is caused by a single amino acid change, S662➔G, in the human PER2 protein.[30][31]

Criteria

[edit]To be called circadian, a biological rhythm must meet these three general criteria:[32]

- The rhythm has an endogenously derived free-running period of time that lasts approximately 24 hours. The rhythm persists in constant conditions, i.e. constant darkness, with a period of about 24 hours. The period of the rhythm in constant conditions is called the free-running period and is denoted by the Greek letter τ (tau). The rationale for this criterion is to distinguish circadian rhythms from simple responses to daily external cues. A rhythm cannot be said to be endogenous unless it has been tested and persists in conditions without external periodic input. In diurnal animals (active during daylight hours), in general τ is slightly greater than 24 hours, whereas, in nocturnal animals (active at night), in general τ is shorter than 24 hours.[citation needed]

- The rhythms are entrainable. The rhythm can be reset by exposure to external stimuli (such as light and heat), a process called entrainment. The external stimulus used to entrain a rhythm is called the zeitgeber, or "time giver". Travel across time zones illustrates the ability of the human biological clock to adjust to the local time; a person will usually experience jet lag before entrainment of their circadian clock has brought it into sync with local time.

- The rhythms exhibit temperature compensation. In other words, they maintain circadian periodicity over a range of physiological temperatures. Many organisms live at a broad range of temperatures, and differences in thermal energy will affect the kinetics of all molecular processes in their cell(s). In order to keep track of time, the organism's circadian clock must maintain roughly a 24-hour periodicity despite the changing kinetics, a property known as temperature compensation. The Q10 temperature coefficient is a measure of this compensating effect. If the Q10 coefficient remains approximately 1 as temperature increases, the rhythm is considered to be temperature-compensated.

Origin

[edit]This section is missing information about independently evolved four times [PMID 11533719]. (September 2021) |

Circadian rhythms allow organisms to anticipate and prepare for precise and regular environmental changes. They thus enable organisms to make better use of environmental resources (e.g. light and food) compared to those that cannot predict such availability. It has therefore been suggested that circadian rhythms put organisms at a selective advantage in evolutionary terms. However, rhythmicity appears to be as important in regulating and coordinating internal metabolic processes, as in coordinating with the environment.[33] This is suggested by the maintenance (heritability) of circadian rhythms in fruit flies after several hundred generations in constant laboratory conditions,[34] as well as in creatures in constant darkness in the wild, and by the experimental elimination of behavioral—but not physiological—circadian rhythms in quail.[35][36]

What drove circadian rhythms to evolve has been an enigmatic question. Previous hypotheses emphasized that photosensitive proteins and circadian rhythms may have originated together in the earliest cells, with the purpose of protecting replicating DNA from high levels of damaging ultraviolet radiation during the daytime. As a result, replication was relegated to the dark. However, evidence for this is lacking: in fact the simplest organisms with a circadian rhythm, the cyanobacteria, do the opposite of this: they divide more in the daytime.[37] Recent studies instead highlight the importance of co-evolution of redox proteins with circadian oscillators in all three domains of life following the Great Oxidation Event approximately 2.3 billion years ago.[1][4] The current view is that circadian changes in environmental oxygen levels and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the presence of daylight are likely to have driven a need to evolve circadian rhythms to preempt, and therefore counteract, damaging redox reactions on a daily basis.

The simplest known circadian clocks are bacterial circadian rhythms, exemplified by the prokaryote cyanobacteria. Recent research has demonstrated that the circadian clock of Synechococcus elongatus can be reconstituted in vitro with just the three proteins (KaiA, KaiB, KaiC)[38] of their central oscillator. This clock has been shown to sustain a 22-hour rhythm over several days upon the addition of ATP. Previous explanations of the prokaryotic circadian timekeeper were dependent upon a DNA transcription/translation feedback mechanism.[citation needed]

A defect in the human homologue of the Drosophila "period" gene was identified as a cause of the sleep disorder FASPS (Familial advanced sleep phase syndrome), underscoring the conserved nature of the molecular circadian clock through evolution. Many more genetic components of the biological clock are now known. Their interactions result in an interlocked feedback loop of gene products resulting in periodic fluctuations that the cells of the body interpret as a specific time of the day.[39]

It is now known that the molecular circadian clock can function within a single cell. That is, it is cell-autonomous.[40] This was shown by Gene Block in isolated mollusk basal retinal neurons (BRNs).[41] At the same time, different cells may communicate with each other resulting in a synchronized output of electrical signaling. These may interface with endocrine glands of the brain to result in periodic release of hormones. The receptors for these hormones may be located far across the body and synchronize the peripheral clocks of various organs. Thus, the information of the time of the day as relayed by the eyes travels to the clock in the brain, and, through that, clocks in the rest of the body may be synchronized. This is how the timing of, for example, sleep/wake, body temperature, thirst, and appetite are coordinately controlled by the biological clock.[42][43]

Importance in animals

[edit]Circadian rhythmicity is present in the sleeping and feeding patterns of animals, including human beings. There are also clear patterns of core body temperature, brain wave activity, hormone production, cell regeneration, and other biological activities. In addition, photoperiodism, the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night, is vital to both plants and animals, and the circadian system plays a role in the measurement and interpretation of day length. Timely prediction of seasonal periods of weather conditions, food availability, or predator activity is crucial for survival of many species. Although not the only parameter, the changing length of the photoperiod (day length) is the most predictive environmental cue for the seasonal timing of physiology and behavior, most notably for timing of migration, hibernation, and reproduction.[44]

Effect of circadian disruption

[edit]Mutations or deletions of clock genes in mice have demonstrated the importance of body clocks to ensure the proper timing of cellular/metabolic events; clock-mutant mice are hyperphagic and obese, and have altered glucose metabolism.[45] In mice, deletion of the Rev-ErbA alpha clock gene can result in diet-induced obesity and changes the balance between glucose and lipid utilization, predisposing to diabetes.[46] However, it is not clear whether there is a strong association between clock gene polymorphisms in humans and the susceptibility to develop the metabolic syndrome.[47][48]

Effect of light–dark cycle

[edit]The rhythm is linked to the light–dark cycle. Animals, including humans, kept in total darkness for extended periods eventually function with a free-running rhythm. Their sleep cycle is pushed back or forward each "day", depending on whether their "day", their endogenous period, is shorter or longer than 24 hours. The environmental cues that reset the rhythms each day are called zeitgebers.[49] Totally blind subterranean mammals (e.g., blind mole rat Spalax sp.) are able to maintain their endogenous clocks in the apparent absence of external stimuli. Although they lack image-forming eyes, their photoreceptors (which detect light) are still functional; they do surface periodically as well.[page needed][50]

Free-running organisms that normally have one or two consolidated sleep episodes will still have them when in an environment shielded from external cues, but the rhythm is not entrained to the 24-hour light–dark cycle in nature. The sleep–wake rhythm may, in these circumstances, become out of phase with other circadian or ultradian rhythms such as metabolic, hormonal, CNS electrical, or neurotransmitter rhythms.[51]

Recent research has influenced the design of spacecraft environments, as systems that mimic the light–dark cycle have been found to be highly beneficial to astronauts.[unreliable medical source?][52] Light therapy has been trialed as a treatment for sleep disorders.

Arctic animals

[edit]Norwegian researchers at the University of Tromsø have shown that some Arctic animals (e.g., ptarmigan, reindeer) show circadian rhythms only in the parts of the year that have daily sunrises and sunsets. In one study of reindeer, animals at 70 degrees North showed circadian rhythms in the autumn, winter and spring, but not in the summer. Reindeer on Svalbard at 78 degrees North showed such rhythms only in autumn and spring. The researchers suspect that other Arctic animals as well may not show circadian rhythms in the constant light of summer and the constant dark of winter.[53]

A 2006 study in northern Alaska found that day-living ground squirrels and nocturnal porcupines strictly maintain their circadian rhythms through 82 days and nights of sunshine. The researchers speculate that these two rodents notice that the apparent distance between the sun and the horizon is shortest once a day, and thus have a sufficient signal to entrain (adjust) by.[54]

Butterflies and moths

[edit]The navigation of the fall migration of the Eastern North American monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) to their overwintering grounds in central Mexico uses a time-compensated sun compass that depends upon a circadian clock in their antennae.[55][56] Circadian rhythm is also known to control mating behavioral in certain moth species such as Spodoptera littoralis, where females produce a specific pheromone that attracts and resets the male circadian rhythm to induce mating at night.[57]

Other synchronizers of circadian rhythms

[edit]Although light is the primary synchronizer of the circadian rhythm through the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), other environmental signals also influence the biological clock. Feeding plays a key role in regulating peripheral clocks found in the liver, muscles, and adipose tissues. Time-restricted feeding can adjust these clocks by modifying light signals. Additionally, physical activity affects the circadian phase, notably by adjusting melatonin production and body temperature. Temperature itself is an important synchronizer, capable of modifying cellular circadian rhythms. Finally, stress and the release of glucocorticoids influence the expression of clock genes, potentially disrupting biological cycles. Integrating these factors is essential for understanding circadian rhythms beyond simple light regulation.[58]

In plants

[edit]

Plant circadian rhythms tell the plant what season it is and when to flower for the best chance of attracting pollinators. Behaviors showing rhythms include leaf movement (Nyctinasty), growth, germination, stomatal/gas exchange, enzyme activity, photosynthetic activity, and fragrance emission, among others.[59] Circadian rhythms occur as a plant entrains to synchronize with the light cycle of its surrounding environment. These rhythms are endogenously generated, self-sustaining and are relatively constant over a range of ambient temperatures. Important features include two interacting transcription-translation feedback loops: proteins containing PAS domains, which facilitate protein-protein interactions; and several photoreceptors that fine-tune the clock to different light conditions. Anticipation of changes in the environment allows appropriate changes in a plant's physiological state, conferring an adaptive advantage.[60] A better understanding of plant circadian rhythms has applications in agriculture, such as helping farmers stagger crop harvests to extend crop availability and securing against massive losses due to weather.

Light is the signal by which plants synchronize their internal clocks to their environment and is sensed by a wide variety of photoreceptors. Red and blue light are absorbed through several phytochromes and cryptochromes. Phytochrome A, phyA, is light labile and allows germination and de-etiolation when light is scarce.[61] Phytochromes B–E are more stable with phyB, the main phytochrome in seedlings grown in the light. The cryptochrome (cry) gene is also a light-sensitive component of the circadian clock and is thought to be involved both as a photoreceptor and as part of the clock's endogenous pacemaker mechanism. Cryptochromes 1–2 (involved in blue–UVA) help to maintain the period length in the clock through a whole range of light conditions.[59][60]

The central oscillator generates a self-sustaining rhythm and is driven by two interacting feedback loops that are active at different times of day. The morning loop consists of CCA1 (Circadian and Clock-Associated 1) and LHY (Late Elongated Hypocotyl), which encode closely related MYB transcription factors that regulate circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis, as well as PRR 7 and 9 (Pseudo-Response Regulators.) The evening loop consists of GI (Gigantea) and ELF4, both involved in regulation of flowering time genes.[62][63] When CCA1 and LHY are overexpressed (under constant light or dark conditions), plants become arrhythmic, and mRNA signals reduce, contributing to a negative feedback loop. Gene expression of CCA1 and LHY oscillates and peaks in the early morning, whereas TOC1 gene expression oscillates and peaks in the early evening. While it was previously hypothesised that these three genes model a negative feedback loop in which over-expressed CCA1 and LHY repress TOC1 and over-expressed TOC1 is a positive regulator of CCA1 and LHY,[60] it was shown in 2012 by Andrew Millar and others that TOC1, in fact, serves as a repressor not only of CCA1, LHY, and PRR7 and 9 in the morning loop but also of GI and ELF4 in the evening loop. This finding and further computational modeling of TOC1 gene functions and interactions suggest a reframing of the plant circadian clock as a triple negative-component repressilator model rather than the positive/negative-element feedback loop characterizing the clock in mammals.[64]

In 2018, researchers found that the expression of PRR5 and TOC1 hnRNA nascent transcripts follows the same oscillatory pattern as processed mRNA transcripts rhythmically in A. thaliana. LNKs binds to the 5'region of PRR5 and TOC1 and interacts with RNAP II and other transcription factors. Moreover, RVE8-LNKs interaction enables a permissive histone-methylation pattern (H3K4me3) to be modified and the histone-modification itself parallels the oscillation of clock gene expression.[65]

It has previously been found that matching a plant's circadian rhythm to its external environment's light and dark cycles has the potential to positively affect the plant.[66] Researchers came to this conclusion by performing experiments on three different varieties of Arabidopsis thaliana. One of these varieties had a normal 24-hour circadian cycle.[66] The other two varieties were mutated, one to have a circadian cycle of more than 27 hours, and one to have a shorter than normal circadian cycle of 20 hours.[66]

The Arabidopsis with the 24-hour circadian cycle was grown in three different environments.[66] One of these environments had a 20-hour light and dark cycle (10 hours of light and 10 hours of dark), the other had a 24-hour light and dark cycle (12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark), and the final environment had a 28-hour light and dark cycle (14 hours of light and 14 hours of dark).[66] The two mutated plants were grown in both an environment that had a 20-hour light and dark cycle and in an environment that had a 28-hour light and dark cycle.[66] It was found that the variety of Arabidopsis with a 24-hour circadian rhythm cycle grew best in an environment that also had a 24-hour light and dark cycle.[66] Overall, it was found that all the varieties of Arabidopsis thaliana had greater levels of chlorophyll and increased growth in environments whose light and dark cycles matched their circadian rhythm.[66]

Researchers suggested that a reason for this could be that matching an Arabidopsis's circadian rhythm to its environment could allow the plant to be better prepared for dawn and dusk, and thus be able to better synchronize its processes.[66] In this study, it was also found that the genes that help to control chlorophyll peaked a few hours after dawn.[66] This appears to be consistent with the proposed phenomenon known as metabolic dawn.[67]

According to the metabolic dawn hypothesis, sugars produced by photosynthesis have potential to help regulate the circadian rhythm and certain photosynthetic and metabolic pathways.[67][68] As the sun rises, more light becomes available, which normally allows more photosynthesis to occur.[67] The sugars produced by photosynthesis repress PRR7.[69] This repression of PRR7 then leads to the increased expression of CCA1.[69] On the other hand, decreased photosynthetic sugar levels increase PRR7 expression and decrease CCA1 expression.[67] This feedback loop between CCA1 and PRR7 is what is proposed to cause metabolic dawn.[67][70]

In Drosophila

[edit]

The molecular mechanism of circadian rhythm and light perception are best understood in Drosophila. Clock genes are discovered from Drosophila, and they act together with the clock neurones. There are two unique rhythms, one during the process of hatching (called eclosion) from the pupa, and the other during mating.[71] The clock neurones are located in distinct clusters in the central brain. The best-understood clock neurones are the large and small lateral ventral neurons (l-LNvs and s-LNvs) of the optic lobe. These neurones produce pigment dispersing factor (PDF), a neuropeptide that acts as a circadian neuromodulator between different clock neurones.[72]

Drosophila circadian rhythm is through a transcription-translation feedback loop. The core clock mechanism consists of two interdependent feedback loops, namely the PER/TIM loop and the CLK/CYC loop.[73] The CLK/CYC loop occurs during the day and initiates the transcription of the per and tim genes. But their proteins levels remain low until dusk, because during daylight also activates the doubletime (dbt) gene. DBT protein causes phosphorylation and turnover of monomeric PER proteins.[74][75] TIM is also phosphorylated by shaggy until sunset. After sunset, DBT disappears, so that PER molecules stably bind to TIM. PER/TIM dimer enters the nucleus several at night, and binds to CLK/CYC dimers. Bound PER completely stops the transcriptional activity of CLK and CYC.[76]

In the early morning, light activates the cry gene and its protein CRY causes the breakdown of TIM. Thus PER/TIM dimer dissociates, and the unbound PER becomes unstable. PER undergoes progressive phosphorylation and ultimately degradation. Absence of PER and TIM allows activation of clk and cyc genes. Thus, the clock is reset to start the next circadian cycle.[77]

PER-TIM model

[edit]This protein model was developed based on the oscillations of the PER and TIM proteins in the Drosophila.[78] It is based on its predecessor, the PER model where it was explained how the PER gene and its protein influence the biological clock.[79] The model includes the formation of a nuclear PER-TIM complex which influences the transcription of the PER and the TIM genes (by providing negative feedback) and the multiple phosphorylation of these two proteins. The circadian oscillations of these two proteins seem to synchronise with the light-dark cycle even if they are not necessarily dependent on it.[80][78] Both PER and TIM proteins are phosphorylated and after they form the PER-TIM nuclear complex they return inside the nucleus to stop the expression of the PER and TIM mRNA. This inhibition lasts as long as the protein, or the mRNA is not degraded.[78] When this happens, the complex releases the inhibition. Here can also be mentioned that the degradation of the TIM protein is sped up by light.[80]

In mammals

[edit]

The primary circadian clock in mammals is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (or nuclei) (SCN), a pair of distinct groups of cells located in the hypothalamus. Destruction of the SCN results in the complete absence of a regular sleep–wake rhythm. The SCN receives information about illumination through the eyes. The retina of the eye contains "classical" photoreceptors ("rods" and "cones"), which are used for conventional vision. But the retina also contains specialized ganglion cells that are directly photosensitive, and project directly to the SCN, where they help in the entrainment (synchronization) of this master circadian clock. The proteins involved in the SCN clock are homologous to those found in the fruit fly.[81]

These cells contain the photopigment melanopsin and their signals follow a pathway called the retinohypothalamic tract, leading to the SCN. If cells from the SCN are removed and cultured, they maintain their own rhythm in the absence of external cues.[82]

The SCN takes the information on the lengths of the day and night from the retina, interprets it, and passes it on to the pineal gland, a tiny structure shaped like a pine cone and located on the epithalamus. In response, the pineal secretes the hormone melatonin.[83] Secretion of melatonin peaks at night and ebbs during the day and its presence provides information about night-length.

Several studies have indicated that pineal melatonin feeds back on SCN rhythmicity to modulate circadian patterns of activity and other processes. However, the nature and system-level significance of this feedback are unknown.[84]

The circadian rhythms of humans can be entrained to slightly shorter and longer periods than the Earth's 24 hours. Researchers at Harvard have shown that human subjects can at least be entrained to a 23.5-hour cycle and a 24.65-hour cycle.[85]

Humans

[edit]

Early research into circadian rhythms suggested that most people preferred a day closer to 25 hours when isolated from external stimuli like daylight and timekeeping. However, this research was faulty because it failed to shield the participants from artificial light. Although subjects were shielded from time cues (like clocks) and daylight, the researchers were not aware of the phase-delaying effects of indoor electric lights.[86][dubious – discuss] The subjects were allowed to turn on light when they were awake and to turn it off when they wanted to sleep. Electric light in the evening delayed their circadian phase.[87] A more stringent study conducted in 1999 by Harvard University estimated the natural human rhythm to be closer to 24 hours and 11 minutes: much closer to the solar day.[88] Consistent with this research was a more recent study from 2010, which also identified sex differences, with the circadian period for women being slightly shorter (24.09 hours) than for men (24.19 hours).[89] In this study, women tended to wake up earlier than men and exhibit a greater preference for morning activities than men, although the underlying biological mechanisms for these differences are unknown.[89]

Biological markers and effects

[edit]The classic phase markers for measuring the timing of a mammal's circadian rhythm are:

- melatonin secretion by the pineal gland,[90]

- core body temperature minimum,[90] and

- plasma level of cortisol.[91]

For temperature studies, subjects must remain awake but calm and semi-reclined in near darkness while their rectal temperatures are taken continuously. Though variation is great among normal chronotypes, the average human adult's temperature reaches its minimum at about 5:00 a.m., about two hours before habitual wake time. Baehr et al.[92] found that, in young adults, the daily body temperature minimum occurred at about 04:00 (4 a.m.) for morning types, but at about 06:00 (6 a.m.) for evening types. This minimum occurred at approximately the middle of the eight-hour sleep period for morning types, but closer to waking in evening types.

Melatonin is absent from the system or undetectably low during daytime. Its onset in dim light, dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO), at roughly 21:00 (9 p.m.) can be measured in the blood or the saliva. Its major metabolite can also be measured in morning urine. Both DLMO and the midpoint (in time) of the presence of the hormone in the blood or saliva have been used as circadian markers. However, newer research indicates that the melatonin offset may be the more reliable marker. Benloucif et al.[90] found that melatonin phase markers were more stable and more highly correlated with the timing of sleep than the core temperature minimum. They found that both sleep offset and melatonin offset are more strongly correlated with phase markers than the onset of sleep. In addition, the declining phase of the melatonin levels is more reliable and stable than the termination of melatonin synthesis.

Other physiological changes that occur according to a circadian rhythm include heart rate and many cellular processes "including oxidative stress, cell metabolism, immune and inflammatory responses,[93] epigenetic modification, hypoxia/hyperoxia response pathways, endoplasmic reticular stress, autophagy, and regulation of the stem cell environment."[94] In a study of young men, it was found that the heart rate reaches its lowest average rate during sleep, and its highest average rate shortly after waking.[95]

In contradiction to previous studies, it has been found that there is no effect of body temperature on performance on psychological tests. This is likely due to evolutionary pressures for higher cognitive function compared to the other areas of function examined in previous studies.[96]

Outside the "master clock"

[edit]More-or-less independent circadian rhythms are found in many organs and cells in the body outside the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), the "master clock". Indeed, neuroscientist Joseph Takahashi and colleagues stated in a 2013 article that "almost every cell in the body contains a circadian clock".[97] For example, these clocks, called peripheral oscillators, have been found in the adrenal gland, oesophagus, lungs, liver, pancreas, spleen, thymus, and skin.[98][99][100] There is also some evidence that the olfactory bulb[101] and prostate[102] may experience oscillations, at least when cultured.

Though oscillators in the skin respond to light, a systemic influence has not been proven.[103] In addition, many oscillators, such as liver cells, for example, have been shown to respond to inputs other than light, such as feeding.[104]

Light and the biological clock

[edit]

Light resets the biological clock in accordance with the phase response curve (PRC). Depending on the timing, light can advance or delay the circadian rhythm. Both the PRC and the required illuminance vary from species to species, and lower light levels are required to reset the clocks in nocturnal rodents than in humans.[105] Light systems designed to support circadian rhythms, such as the CircadianLux ceiling round, can dynamically adjust lighting levels based on metrics such as melanopic equivalent daylight illuminance (M-EDI), aiming to better support the biological clock[106].

Enforced longer or shorter cycles

[edit]Various studies on humans have made use of enforced sleep/wake cycles strongly different from 24 hours, such as those conducted by Nathaniel Kleitman in 1938 (28 hours) and Derk-Jan Dijk and Charles Czeisler in the 1990s (20 hours). Because people with a normal (typical) circadian clock cannot entrain to such abnormal day/night rhythms,[107] this is referred to as a forced desynchrony protocol. Under such a protocol, sleep and wake episodes are uncoupled from the body's endogenous circadian period, which allows researchers to assess the effects of circadian phase (i.e., the relative timing of the circadian cycle) on aspects of sleep and wakefulness including sleep latency and other functions - both physiological, behavioral, and cognitive.[108][109][110][111][112]

Studies also show that Cyclosa turbinata is unique in that its locomotor and web-building activity cause it to have an exceptionally short-period circadian clock, about 19 hours. When C. turbinata spiders are placed into chambers with periods of 19, 24, or 29 hours of evenly split light and dark, none of the spiders exhibited decreased longevity in their own circadian clock. These findings suggest that C. turbinata do not have the same costs of extreme desynchronization as do other species of animals.

Human health

[edit]

Foundation of circadian medicine

[edit]The leading edge of circadian biology research is translation of basic body clock mechanisms into clinical tools, and this is especially relevant to the treatment of cardiovascular disease.[113][114][115][116] Timing of medical treatment in coordination with the body clock, chronotherapeutics, may also benefit patients with hypertension (high blood pressure) by significantly increasing efficacy and reduce drug toxicity or adverse reactions.[117] 3) "Circadian Pharmacology" or drugs targeting the circadian clock mechanism have been shown experimentally in rodent models to significantly reduce the damage due to heart attacks and prevent heart failure.[118] Importantly, for rational translation of the most promising Circadian Medicine therapies to clinical practice, it is imperative that we understand how it helps treat disease in both biological sexes.[119][120][121][122]

Causes of disruption to circadian rhythms

[edit]Indoor lighting

[edit]Lighting requirements for circadian regulation are not simply the same as those for vision; planning of indoor lighting in offices and institutions is beginning to take this into account.[123] Animal studies on the effects of light in laboratory conditions have until recently considered light intensity (irradiance) but not color, which can be shown to "act as an essential regulator of biological timing in more natural settings".[124]

Blue LED lighting suppresses melatonin production five times more than the orange-yellow high-pressure sodium (HPS) light; a metal halide lamp, which is white light, suppresses melatonin at a rate more than three times greater than HPS.[125] Depression symptoms from long term nighttime light exposure can be undone by returning to a normal cycle.[126]

Airline pilots and cabin crew

[edit]Due to the nature of work of airline pilots, who often cross several time zones and regions of sunlight and darkness in one day, and spend many hours awake both day and night, they are often unable to maintain sleep patterns that correspond to the natural human circadian rhythm; this situation can easily lead to fatigue. The NTSB cites this as contributing to many accidents,[127] and has conducted several research studies in order to find methods of combating fatigue in pilots.[128]

Effect of drugs

[edit]Studies conducted on both animals and humans show major bidirectional relationships between the circadian system and abusive drugs. It is indicated that these abusive drugs affect the central circadian pacemaker. Individuals with substance use disorder display disrupted rhythms. These disrupted rhythms can increase the risk for substance abuse and relapse. It is possible that genetic and/or environmental disturbances to the normal sleep and wake cycle can increase the susceptibility to addiction.[129]

It is difficult to determine if a disturbance in the circadian rhythm is at fault for an increase in prevalence for substance abuse—or if other environmental factors such as stress are to blame. Changes to the circadian rhythm and sleep occur once an individual begins abusing drugs and alcohol. Once an individual stops using drugs and alcohol, the circadian rhythm continues to be disrupted.[129]

Alcohol consumption disrupts circadian rhythms, with acute intake causing dose-dependent alterations in melatonin and cortisol levels, as well as core body temperature, which normalize the following morning, while chronic alcohol use leads to more severe and persistent disruptions that are associated with alcohol use disorders (AUD) and withdrawal symptoms.[130]

The stabilization of sleep and the circadian rhythm might possibly help to reduce the vulnerability to addiction and reduce the chances of relapse.[129]

Circadian rhythms and clock genes expressed in brain regions outside the suprachiasmatic nucleus may significantly influence the effects produced by drugs such as cocaine.[131] Moreover, genetic manipulations of clock genes profoundly affect cocaine's actions.[132]

Consequences of disruption to circadian rhythms

[edit]Disruption

[edit]Disruption to rhythms usually has a negative effect. Many travelers have experienced the condition known as jet lag, with its associated symptoms of fatigue, disorientation and insomnia.[133]

A number of other disorders, such as bipolar disorder, depression, and some sleep disorders such as delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD), are associated with irregular or pathological functioning of circadian rhythms.[134][135][136][137]

Disruption to rhythms in the longer term is believed to have significant adverse health consequences for peripheral organs outside the brain, in particular in the development or exacerbation of cardiovascular disease.[138][139]

Studies have shown that maintaining normal sleep and circadian rhythms is important for many aspects of brain and health.[138] A number of studies have also indicated that a power-nap, a short period of sleep during the day, can reduce stress and may improve productivity without any measurable effect on normal circadian rhythms.[140][141][142] Circadian rhythms also play a part in the reticular activating system, which is crucial for maintaining a state of consciousness. A reversal[clarification needed] in the sleep–wake cycle may be a sign or complication of uremia,[143] azotemia or acute kidney injury.[144][145] Studies have also helped elucidate how light has a direct effect on human health through its influence on the circadian biology.[146]

Relationship with cardiovascular disease

[edit]One of the first studies to determine how disruption of circadian rhythms causes cardiovascular disease was performed in the Tau hamsters, which have a genetic defect in their circadian clock mechanism.[147] When maintained in a 24-hour light-dark cycle that was "out of sync" with their normal 22 circadian mechanism they developed profound cardiovascular and renal disease; however, when the Tau animals were raised for their entire lifespan on a 22-hour daily light-dark cycle they had a healthy cardiovascular system.[147] The adverse effects of circadian misalignment on human physiology has been studied in the laboratory using a misalignment protocol,[148][149] and by studying shift workers.[113][150][151] Circadian misalignment is associated with many risk factors of cardiovascular disease. High levels of the atherosclerosis biomarker, resistin, have been reported in shift workers indicating the link between circadian misalignment and plaque build up in arteries.[151] Additionally, elevated triacylglyceride levels (molecules used to store excess fatty acids) were observed and contribute to the hardening of arteries, which is associated with cardiovascular diseases including heart attack, stroke and heart disease.[151][152] Shift work and the resulting circadian misalignment is also associated with hypertension.[153]

Obesity and diabetes

[edit]Obesity and diabetes are associated with lifestyle and genetic factors. Among those factors, disruption of the circadian clockwork and/or misalignment of the circadian timing system with the external environment (e.g., light–dark cycle) can play a role in the development of metabolic disorders.[138]

Shift work or chronic jet lag have profound consequences for circadian and metabolic events in the body. Animals that are forced to eat during their resting period show increased body mass and altered expression of clock and metabolic genes.[154][152] In humans, shift work that favours irregular eating times is associated with altered insulin sensitivity, diabetes and higher body mass.[153][152][155]

Cognitive effects

[edit]Reduced cognitive function has been associated with circadian misalignment. Chronic shift workers display increased rates of operational error, impaired visual-motor performance and processing efficacy which can lead to both a reduction in performance and potential safety issues.[156] Increased risk of dementia is associated with chronic night shift workers compared to day shift workers, particularly for individuals over 50 years old.[157][158][159]

Society and culture

[edit]In 2017, Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael W. Young, and Michael Rosbash were awarded Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm".[160][161]

Circadian rhythms was taken as an example of scientific knowledge being transferred into the public sphere.[162]

See also

[edit]- Actigraphy (also known as actimetry)

- ARNTL

- ARNTL2

- Bacterial circadian rhythms

- Circadian rhythm sleep disorders, such as

- Chronobiology

- Chronodisruption

- CLOCK

- Circasemidian rhythm

- Circaseptan, 7-day biological cycle

- Cryptochrome

- CRY1 and CRY2: the cryptochrome family genes

- Diurnal cycle

- Light effects on circadian rhythm

- Light in school buildings

- PER1, PER2, and PER3: the period family genes

- Photosensitive ganglion cell: part of the eye which is involved in regulating circadian rhythm.

- Polyphasic sleep

- Rev-ErbA alpha

- Segmented sleep

- Sleep architecture (sleep in humans)

- Sleep in non-human animals

- Stefania Follini

- Ultradian rhythm

References

[edit]- ^ a b Edgar RS, Green EW, Zhao Y, van Ooijen G, Olmedo M, Qin X, et al. (May 2012). "Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms". Nature. 485 (7399): 459–464. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..459E. doi:10.1038/nature11088. PMC 3398137. PMID 22622569.

- ^ Young MW, Kay SA (September 2001). "Time zones: a comparative genetics of circadian clocks". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 2 (9): 702–715. doi:10.1038/35088576. PMID 11533719. S2CID 13286388.

- ^ Vitaterna MH, Takahashi JS, Turek FW (2001). "Overview of circadian rhythms". Alcohol Research & Health. 25 (2): 85–93. PMC 6707128. PMID 11584554.

- ^ a b Bass J (November 2012). "Circadian topology of metabolism". Nature. 491 (7424): 348–356. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..348B. doi:10.1038/nature11704. PMID 23151577. S2CID 27778254.

- ^ Theophrastus, 'Περὶ φυτῶν ἱστορία'. "Enquiry into plants and minor works on odours and weather signs, with an English translation by Sir Arthur Hort, bart 1916". Archived from the original on 2022-04-13.

- ^ Bretzl H (1903). Botanische Forschungen des Alexanderzuges. Leipzig: Teubner.[page needed]

- ^ Lu GD (25 October 2002). Celestial Lancets. Psychology Press. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-0-7007-1458-2.

- ^ de Mairan JJ (1729). "Observation Botanique". Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences: 35–36.

- ^ Gardner MJ, Hubbard KE, Hotta CT, Dodd AN, Webb AA (July 2006). "How plants tell the time". The Biochemical Journal. 397 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1042/BJ20060484. PMC 1479754. PMID 16761955.

- ^ Dijk DJ, von Schantz M (August 2005). "Timing and consolidation of human sleep, wakefulness, and performance by a symphony of oscillators". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 20 (4): 279–290. doi:10.1177/0748730405278292. PMID 16077148. S2CID 13538323.

- ^ Danchin A. "Important dates 1900–1919". HKU-Pasteur Research Centre. Archived from the original on 2003-10-20. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ Antle MC, Silver R (November 2009). "Neural basis of timing and anticipatory behaviors". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (9): 1643–1649. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06959.x. PMC 2929840. PMID 19878281.

- ^ Bruce VG, Pittendrigh CS (1957). "Endogenous Rhythms in Insects and Microorganisms". The American Naturalist. 91 (858): 179–195. Bibcode:1957ANat...91..179B. doi:10.1086/281977. S2CID 83886607.

- ^ a b Pittendrigh CS (1993). "Temporal organization: reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher". Annual Review of Physiology. 55 (1): 16–54. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.000313. PMID 8466172. S2CID 45054898.

- ^ Pittendrigh CS (October 1954). "On Temperature Independence in the Clock System Controlling Emergence Time in Drosophila". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 40 (10): 1018–1029. Bibcode:1954PNAS...40.1018P. doi:10.1073/pnas.40.10.1018. PMC 534216. PMID 16589583.

- ^ Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Katinas G, Syutkina EV, Sothern RB, Zaslavskaya R, et al. (October 2003). "Transdisciplinary unifying implications of circadian findings in the 1950s". Journal of Circadian Rhythms. 1 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/1740-3391-1-2. PMC 317388. PMID 14728726.

Eventually I reverted, for the same reason, to "circadian" ...

- ^ Halberg F (1959). "[Physiologic 24-hour periodicity; general and procedural considerations with reference to the adrenal cycle]". Internationale Zeitschrift für Vitaminforschung. Beiheft. 10: 225–296. PMID 14398945.

- ^ Koukkari WL, Sothern RB (2006). Introducing Biological Rhythms: A Primer on the Temporal Organization of Life, with Implications for Health, Society, Reproduction, and the Natural Environment. New York: Springer. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4020-3691-0.

- ^ Halberg F, Carandente F, Cornelissen G, Katinas GS (1977). "[Glossary of chronobiology (author's transl)]". Chronobiologia. 4 (Suppl 1): 1–189. PMID 352650.

- ^ Konopka RJ, Benzer S (September 1971). "Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 68 (9): 2112–2116. Bibcode:1971PNAS...68.2112K. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. PMC 389363. PMID 5002428.

- ^ Reddy P, Zehring WA, Wheeler DA, Pirrotta V, Hadfield C, Hall JC, et al. (October 1984). "Molecular analysis of the period locus in Drosophila melanogaster and identification of a transcript involved in biological rhythms". Cell. 38 (3): 701–710. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90265-4. PMID 6435882. S2CID 316424.

- ^ Zehring WA, Wheeler DA, Reddy P, Konopka RJ, Kyriacou CP, Rosbash M, et al. (December 1984). "P-element transformation with period locus DNA restores rhythmicity to mutant, arrhythmic Drosophila melanogaster". Cell. 39 (2 Pt 1): 369–376. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90015-1. PMID 6094014.

- ^ Bargiello TA, Jackson FR, Young MW (1984). "Restoration of circadian behavioural rhythms by gene transfer in Drosophila". Nature. 312 (5996): 752–754. Bibcode:1984Natur.312..752B. doi:10.1038/312752a0. PMID 6440029. S2CID 4259316.

- ^ Bargiello TA, Young MW (April 1984). "Molecular genetics of a biological clock in Drosophila". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (7): 2142–2146. Bibcode:1984Natur.312..752B. doi:10.1038/312752a0. PMC 345453. PMID 16593450.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] "Gene Discovered in Mice that Regulates Biological Clock". Chicago Tribune. 29 April 1994.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang AM, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, McDonald JD, et al. (April 1994). "Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior". Science. 264 (5159): 719–725. Bibcode:1994Sci...264..719H. doi:10.1126/science.8171325. PMC 3839659. PMID 8171325.

- ^ Debruyne JP, Noton E, Lambert CM, Maywood ES, Weaver DR, Reppert SM (May 2006). "A clock shock: mouse CLOCK is not required for circadian oscillator function". Neuron. 50 (3): 465–477. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.041. PMID 16675400. S2CID 19028601.

- ^ Collins B, Blau J (May 2006). "Keeping time without a clock". Neuron. 50 (3): 348–350. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.022. PMID 16675389.

- ^ Toh KL, Jones CR, He Y, Eide EJ, Hinz WA, Virshup DM, et al. (February 2001). "An hPer2 phosphorylation site mutation in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome". Science. 291 (5506): 1040–1043. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.1040T. doi:10.1126/science.1057499. PMID 11232563. S2CID 1848310.

- ^ Jones CR, Campbell SS, Zone SE, Cooper F, DeSano A, Murphy PJ, et al. (September 1999). "Familial advanced sleep-phase syndrome: A short-period circadian rhythm variant in humans". Nature Medicine. 5 (9): 1062–1065. doi:10.1038/12502. PMID 10470086. S2CID 14809619.

- ^ Johnson C (2004). Chronobiology: Biological Timekeeping. Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. pp. 67–105.

- ^ Sharma VK (November 2003). "Adaptive significance of circadian clocks". Chronobiology International. 20 (6): 901–919. doi:10.1081/CBI-120026099. PMID 14680135. S2CID 10899279.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Sheeba V, Sharma VK, Chandrashekaran MK, Joshi A (September 1999). "Persistence of eclosion rhythm in Drosophila melanogaster after 600 generations in an aperiodic environment". Die Naturwissenschaften. 86 (9): 448–449. Bibcode:1999NW.....86..448S. doi:10.1007/s001140050651. PMID 10501695. S2CID 13401297.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Guyomarc'h C, Lumineau S, Richard JP (May 1998). "Circadian rhythm of activity in Japanese quail in constant darkness: variability of clarity and possibility of selection". Chronobiology International. 15 (3): 219–230. doi:10.3109/07420529808998685. PMID 9653576.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Zivkovic BD, Underwood H, Steele CT, Edmonds K (October 1999). "Formal properties of the circadian and photoperiodic systems of Japanese quail: phase response curve and effects of T-cycles". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 14 (5): 378–390. doi:10.1177/074873099129000786. PMID 10511005. S2CID 13390422.

- ^ Mori T, Johnson CH (April 2001). "Independence of circadian timing from cell division in cyanobacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 183 (8): 2439–2444. doi:10.1128/JB.183.8.2439-2444.2001. PMC 95159. PMID 11274102.

- ^ Hut RA, Beersma DG (July 2011). "Evolution of time-keeping mechanisms: early emergence and adaptation to photoperiod". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 366 (1574): 2141–2154. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0409. PMC 3130368. PMID 21690131.

- ^ Dubowy C, Sehgal A (April 2017). "Circadian Rhythms and Sleep in Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics. 205 (4): 1373–1397. doi:10.1534/genetics.115.185157. PMC 5378101. PMID 28360128.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Nagoshi E, Saini C, Bauer C, Laroche T, Naef F, Schibler U (November 2004). "Circadian gene expression in individual fibroblasts: cell-autonomous and self-sustained oscillators pass time to daughter cells". Cell. 119 (5): 693–705. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.015. PMID 15550250. S2CID 15633902.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Michel S, Geusz ME, Zaritsky JJ, Block GD (January 1993). "Circadian rhythm in membrane conductance expressed in isolated neurons". Science. 259 (5092): 239–241. Bibcode:1993Sci...259..239M. doi:10.1126/science.8421785. PMID 8421785.

- ^ Refinetti R (January 2010). "The circadian rhythm of body temperature". Frontiers in Bioscience. 15 (2): 564–594. doi:10.2741/3634. PMID 20036834. S2CID 36170900.

- ^ Scheer FA, Morris CJ, Shea SA (March 2013). "The internal circadian clock increases hunger and appetite in the evening independent of food intake and other behaviors". Obesity. 21 (3): 421–423. doi:10.1002/oby.20351. PMC 3655529. PMID 23456944.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Zivkovic BC (2007-07-25). "Clock Tutorial #16: Photoperiodism – Models and Experimental Approaches (original work from 2005-08-13)". A Blog Around the Clock. ScienceBlogs. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Turek FW, Joshu C, Kohsaka A, Lin E, Ivanova G, McDearmon E, et al. (May 2005). "Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice". Science. 308 (5724): 1043–1045. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1043T. doi:10.1126/science.1108750. PMC 3764501. PMID 15845877.

- ^ Delezie J, Dumont S, Dardente H, Oudart H, Gréchez-Cassiau A, Klosen P, et al. (August 2012). "The nuclear receptor REV-ERBα is required for the daily balance of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism". FASEB Journal. 26 (8): 3321–3335. doi:10.1096/fj.12-208751. PMID 22562834. S2CID 31204290.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Delezie J, Dumont S, Dardente H, Oudart H, Gréchez-Cassiau A, Klosen P, et al. (August 2012). "The nuclear receptor REV-ERBα is required for the daily balance of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism". FASEB Journal. 26 (8): 3321–3335. doi:10.1096/fj.12-208751. PMID 22562834. S2CID 31204290.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Scott EM, Carter AM, Grant PJ (April 2008). "Association between polymorphisms in the Clock gene, obesity and the metabolic syndrome in man". International Journal of Obesity. 32 (4): 658–662. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803778. PMID 18071340.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Shneerson JM, Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA (2007). "Circadian rhythms". Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Armenian Medical Network. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ "The Rhythms of Life: The Biological Clocks That Control the Daily Lives of Every Living Thing" Russell Foster & Leon Kreitzman, Publisher: Profile Books Ltd.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Regestein QR, Pavlova M (September 1995). "Treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome". General Hospital Psychiatry. 17 (5): 335–345. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(95)00062-V. PMID 8522148.

- ^ Howell E (14 December 2012). "Space Station to Get New Insomnia-Fighting Light Bulbs". Space.com. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Spilde I (December 2005). "Reinsdyr uten døgnrytme" (in Norwegian Bokmål). forskning.no. Archived from the original on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

...så det ikke ut til at reinen hadde noen døgnrytme om sommeren. Svalbardreinen hadde det heller ikke om vinteren.

- ^ Folk GE, Thrift DL, Zimmerman MB, Reimann P (2006-12-01). "Mammalian activity – rest rhythms in Arctic continuous daylight". Biological Rhythm Research. 37 (6): 455–469. Bibcode:2006BioRR..37..455F. doi:10.1080/09291010600738551. S2CID 84625255.

Would local animals maintained under natural continuous daylight demonstrate the Aschoff effect described in previously published laboratory experiments using continuous light, in which rats' circadian activity patterns changed systematically to a longer period, expressing a 26-hour day of activity and rest?

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Merlin C, Gegear RJ, Reppert SM (September 2009). "Antennal circadian clocks coordinate sun compass orientation in migratory monarch butterflies". Science. 325 (5948): 1700–1704. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1700M. doi:10.1126/science.1176221. PMC 2754321. PMID 19779201.

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Kyriacou CP (September 2009). "Physiology. Unraveling traveling". Science. 325 (5948): 1629–1630. doi:10.1126/science.1178935. PMID 19779177. S2CID 206522416.

- ^ Silvegren G, Löfstedt C, Qi Rosén W (March 2005). "Circadian mating activity and effect of pheromone pre-exposure on pheromone response rhythms in the moth Spodoptera littoralis". Journal of Insect Physiology. 51 (3): 277–286. Bibcode:2005JInsP..51..277S. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.11.013. PMID 15749110.

- ^ Takahashi JS (2017). "Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock". Nature Reviews Genetics. 18 (3): 164–179. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.150. PMC 5501165. PMID 27990019.

- ^ a b Webb AA (November 2003). "The physiology of circadian rhythms in plants". The New Phytologist. 160 (2): 281–303. Bibcode:2003NewPh.160..281W. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00895.x. JSTOR 1514280. PMID 33832173. S2CID 15688409.

- ^ a b c McClung CR (April 2006). "Plant circadian rhythms". The Plant Cell. 18 (4): 792–803. Bibcode:2006PlanC..18..792M. doi:10.1105/tpc.106.040980. PMC 1425852. PMID 16595397.

- ^ Legris M, Ince YÇ, Fankhauser C (November 2019). "Molecular mechanisms underlying phytochrome-controlled morphogenesis in plants". Nature Communications. 10 (1) 5219. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.5219L. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13045-0. PMC 6864062. PMID 31745087.

- ^ Mizoguchi T, Wright L, Fujiwara S, Cremer F, Lee K, Onouchi H, et al. (August 2005). "Distinct roles of GIGANTEA in promoting flowering and regulating circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis". The Plant Cell. 17 (8): 2255–2270. Bibcode:2005PlanC..17.2255M. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.033464. PMC 1182487. PMID 16006578.

- ^ Kolmos E, Davis SJ (September 2007). "ELF4 as a Central Gene in the Circadian Clock". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2 (5): 370–372. Bibcode:2007PlSiB...2..370K. doi:10.4161/psb.2.5.4463. PMC 2634215. PMID 19704602.

- ^ Pokhilko A, Fernández AP, Edwards KD, Southern MM, Halliday KJ, Millar AJ (March 2012). "The clock gene circuit in Arabidopsis includes a repressilator with additional feedback loops". Molecular Systems Biology. 8: 574. doi:10.1038/msb.2012.6. PMC 3321525. PMID 22395476.

- ^ Ma Y, Gil S, Grasser KD, Mas P (April 2018). "Targeted Recruitment of the Basal Transcriptional Machinery by LNK Clock Components Controls the Circadian Rhythms of Nascent RNAs in Arabidopsis". The Plant Cell. 30 (4): 907–924. Bibcode:2018PlanC..30..907M. doi:10.1105/tpc.18.00052. PMC 5973845. PMID 29618629.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dodd AN, Salathia N, Hall A, Kévei E, Tóth R, Nagy F, et al. (July 2005). "Plant circadian clocks increase photosynthesis, growth, survival, and competitive advantage". Science. 309 (5734): 630–633. Bibcode:2005Sci...309..630D. doi:10.1126/science.1115581. PMID 16040710. S2CID 25739247.

- ^ a b c d e Dodd AN, Belbin FE, Frank A, Webb AA (2015). "Interactions between circadian clocks and photosynthesis for the temporal and spatial coordination of metabolism". Frontiers in Plant Science. 6: 245. Bibcode:2015FrPS....6..245D. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00245. PMC 4391236. PMID 25914715.

- ^ Webb AA, Seki M, Satake A, Caldana C (February 2019). "Continuous dynamic adjustment of the plant circadian oscillator". Nature Communications. 10 (1) 550. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..550W. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08398-5. PMC 6358598. PMID 30710080.

- ^ a b Haydon MJ, Mielczarek O, Robertson FC, Hubbard KE, Webb AA (October 2013). "Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock". Nature. 502 (7473): 689–692. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..689H. doi:10.1038/nature12603. PMC 3827739. PMID 24153186.

- ^ Farré EM, Kay SA (November 2007). "PRR7 protein levels are regulated by light and the circadian clock in Arabidopsis". The Plant Journal. 52 (3): 548–560. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03258.x. PMID 17877705.

- ^ Veleri S, Wülbeck C (May 2004). "Unique self-sustaining circadian oscillators within the brain of Drosophila melanogaster". Chronobiology International. 21 (3): 329–342. doi:10.1081/CBI-120038597. PMID 15332440. S2CID 15099796.

- ^ Yoshii T, Hermann-Luibl C, Helfrich-Förster C (2015). "Circadian light-input pathways in Drosophila". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 9 (1) e1102805. doi:10.1080/19420889.2015.1102805. PMC 4802797. PMID 27066180.

- ^ Boothroyd CE, Young MW (2008). "The in(put)s and out(put)s of the Drosophila circadian clock". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1129 (1): 350–357. Bibcode:2008NYASA1129..350B. doi:10.1196/annals.1417.006. PMID 18591494. S2CID 2639040.

- ^ Grima B, Lamouroux A, Chélot E, Papin C, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Rouyer F (November 2002). "The F-box protein slimb controls the levels of clock proteins period and timeless". Nature. 420 (6912): 178–182. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..178G. doi:10.1038/nature01122. PMID 12432393. S2CID 4428779.

- ^ Ko HW, Jiang J, Edery I (December 2002). "Role for Slimb in the degradation of Drosophila Period protein phosphorylated by Doubletime". Nature. 420 (6916): 673–678. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..673K. doi:10.1038/nature01272. PMID 12442174. S2CID 4414176.

- ^ Helfrich-Förster C (March 2005). "Neurobiology of the fruit fly's circadian clock". Genes, Brain and Behavior. 4 (2): 65–76. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00092.x. PMID 15720403. S2CID 26099539.

- ^ Lalchhandama K (2017). "The path to the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Science Vision. 3 (Suppl): 1–13.

- ^ a b c Leloup JC, Goldbeter A (February 1998). "A model for circadian rhythms in Drosophila incorporating the formation of a complex between the PER and TIM proteins". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 13 (1): 70–87. doi:10.1177/074873098128999934. PMID 9486845. S2CID 17944849.

- ^ Goldbeter A (September 1995). "A model for circadian oscillations in the Drosophila period protein (PER)". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 261 (1362): 319–324. Bibcode:1995RSPSB.261..319G. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0153. PMID 8587874. S2CID 7024361.

- ^ a b Goldbeter A (November 2002). "Computational approaches to cellular rhythms". Nature. 420 (6912): 238–245. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..238G. doi:10.1038/nature01259. PMID 12432409. S2CID 452149.

- ^ "Biological Clock in Mammals". BioInteractive. Howard Hughes Medical Institute. 4 February 2000. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Welsh DK, Takahashi JS, Kay SA (March 2010). "Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties". Annual Review of Physiology. 72: 551–77. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135919. PMC 3758475. PMID 20148688.

- ^ Pfeffer M, Korf HW, Wicht H (March 2018). "Synchronizing effects of melatonin on diurnal and circadian rhythms". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 258: 215–221. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.05.013. PMID 28533170.

- ^ Kalpesh J. "Wellness With Artificial Light". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Scheer FA, Wright KP, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA (August 2007). "Plasticity of the intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system". PLOS ONE. 2 (8) e721. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..721S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000721. PMC 1934931. PMID 17684566.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Duffy JF, Wright KP (August 2005). "Entrainment of the human circadian system by light". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 20 (4): 326–38. doi:10.1177/0748730405277983. PMID 16077152. S2CID 20140030.

- ^ Khalsa SB, Jewett ME, Cajochen C, Czeisler CA (June 2003). "A phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjects". The Journal of Physiology. 549 (Pt 3): 945–52. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040477. PMC 2342968. PMID 12717008.

- ^ Cromie W (1999-07-15). "Human Biological Clock Set Back an Hour". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2015-07-04.

- ^ a b Duffy JF, Cain SW, Chang AM, Phillips AJ, Münch MY, Gronfier C, et al. (September 2011). "Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (Supplement_3): 15602–8. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10815602D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010666108. PMC 3176605. PMID 21536890.

- ^ a b c Benloucif S, Guico MJ, Reid KJ, Wolfe LF, L'hermite-Balériaux M, Zee PC (April 2005). "Stability of melatonin and temperature as circadian phase markers and their relation to sleep times in humans". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 20 (2): 178–88. doi:10.1177/0748730404273983. PMID 15834114. S2CID 36360463.

- ^ Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE (September 2017). "Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 83: 25–41. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.018. PMC 5568897. PMID 28578301.

- ^ Baehr EK, Revelle W, Eastman CI (June 2000). "Individual differences in the phase and amplitude of the human circadian temperature rhythm: with an emphasis on morningness-eveningness". Journal of Sleep Research. 9 (2): 117–27. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00196.x. PMID 10849238. S2CID 6104127.

- ^ Seizer L, Cornélissen-Guillaume G, Schiepek GK, Chamson E, Bliem HR and Schubert C (2022) About-Weekly Pattern in the Dynamic Complexity of a Healthy Subject's Cellular Immune Activity: A Biopsychosocial Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 13:799214. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.799214

- ^ "NHLBI Workshop: "Circadian Clock at the Interface of Lung Health and Disease" 28-29 April 2014 Executive Summary". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-10-04. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Degaute JP, van de Borne P, Linkowski P, Van Cauter E (August 1991). "Quantitative analysis of the 24-hour blood pressure and heart rate patterns in young men". Hypertension. 18 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.18.2.199. PMID 1885228.

- ^ Quartel L (2014). "The effect of the circadian rhythm of body temperature on A-level exam performance". Undergraduate Journal of Psychology. 27 (1).

- ^ Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS (July 14, 2013). "Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 35: 445–62. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. PMC 3710582. PMID 22483041.

- ^ Id.

- ^ Pendergast JS, Niswender KD, Yamazaki S (January 11, 2012). "Tissue-specific function of Period3 in circadian rhythmicity". PLOS ONE. 7 (1) e30254. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730254P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030254. PMC 3256228. PMID 22253927.

- ^ Singh M (10 Oct 2013). "Our Skin's Sense Of Time Helps Protect Against UV Damage". NPR. Retrieved 19 Feb 2019.

- ^ Abraham U, Granada AE, Westermark PO, Heine M, Kramer A, Herzel H (November 2010). "Coupling governs entrainment range of circadian clocks". Molecular Systems Biology. 6: 438. doi:10.1038/msb.2010.92. PMC 3010105. PMID 21119632.

- ^ Cao Q, Gery S, Dashti A, Yin D, Zhou Y, Gu J, et al. (October 2009). "A role for the clock gene per1 in prostate cancer". Cancer Research. 69 (19): 7619–25. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4199. PMC 2756309. PMID 19752089.

- ^ Kawara S, Mydlarski R, Mamelak AJ, Freed I, Wang B, Watanabe H, et al. (December 2002). "Low-dose ultraviolet B rays alter the mRNA expression of the circadian clock genes in cultured human keratinocytes". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 119 (6): 1220–3. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19619.x. PMID 12485420.

- ^ Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U (December 2000). "Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus". Genes & Development. 14 (23): 2950–61. doi:10.1101/gad.183500. PMC 317100. PMID 11114885.

- ^ Duffy JF, Czeisler CA (June 2009). "Effect of Light on Human Circadian Physiology". Sleep Medicine Clinics. 4 (2): 165–177. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.01.004. PMC 2717723. PMID 20161220.

- ^ Kuipers J, Cheung B (July 2025). A Circadian Lighting System For Care Facilities For Older People: A Practical Example To Support Sleep And Wellbeing. International Conference of Dementia Innovation Readiness. Hong Kong.

- ^ Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, et al. (June 1999). "Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker". Science. 284 (5423): 2177–81. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2177. PMID 10381883. S2CID 8516106.

- ^ Aldrich MS (1999). Sleep medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512957-1.

- ^ Wyatt JK, Ritz-De Cecco A, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ (October 1999). "Circadian temperature and melatonin rhythms, sleep, and neurobehavioral function in humans living on a 20-h day". The American Journal of Physiology. 277 (4 Pt 2): R1152-63. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.4.R1152. PMID 10516257. S2CID 4474347.

- ^ Wright KP, Hull JT, Czeisler CA (December 2002). "Relationship between alertness, performance, and body temperature in humans". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 283 (6): R1370-7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1030.9291. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00205.2002. PMID 12388468.

- ^ Zhou X, Ferguson SA, Matthews RW, Sargent C, Darwent D, Kennaway DJ, et al. (July 2011). "Sleep, wake and phase dependent changes in neurobehavioral function under forced desynchrony". Sleep. 34 (7): 931–41. doi:10.5665/SLEEP.1130. PMC 3119835. PMID 21731143.

- ^ Kosmadopoulos A, Sargent C, Darwent D, Zhou X, Dawson D, Roach GD (December 2014). "The effects of a split sleep-wake schedule on neurobehavioural performance and predictions of performance under conditions of forced desynchrony". Chronobiology International. 31 (10): 1209–17. doi:10.3109/07420528.2014.957763. PMID 25222348. S2CID 11643058.

- ^ a b Alibhai FJ, Tsimakouridze EV, Reitz CJ, Pyle WG, Martino TA (July 2015). "Consequences of Circadian and Sleep Disturbances for the Cardiovascular System". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 31 (7): 860–872. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.015. PMID 26031297.

- ^ Martino TA, Young ME (June 2015). "Influence of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock on cardiac physiology and pathophysiology". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 30 (3): 183–205. doi:10.1177/0748730415575246. PMID 25800587. S2CID 21868234.

- ^ Mistry P, Duong A, Kirshenbaum L, Martino TA (October 2017). "Cardiac Clocks and Preclinical Translation". Heart Failure Clinics. 13 (4): 657–672. doi:10.1016/j.hfc.2017.05.002. PMID 28865775.

- ^ Aziz IS, McMahon AM, Friedman D, Rabinovich-Nikitin I, Kirshenbaum LA, Martino TA (April 2021). "Circadian influence on inflammatory response during cardiovascular disease". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 57: 60–70. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2020.11.007. PMID 33340915. S2CID 229332749.

- ^ Grote L, Mayer J, Penzel T, Cassel W, Krzyzanek E, Peter JH, et al. (1994). "Nocturnal hypertension and cardiovascular risk: consequences for diagnosis and treatment". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 24 (Suppl 2): S26 – S38. doi:10.1097/00005344-199412001-00006. PMID 7898092.

- ^ Reitz CJ, Alibhai FJ, Khatua TN, Rasouli M, Bridle BW, Burris TP, et al. (2019). "SR9009 administered for one day after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion prevents heart failure in mice by targeting the cardiac inflammasome". Communications Biology. 2 353. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0595-z. PMC 6776554. PMID 31602405.

- ^ Alibhai FJ, Reitz CJ, Peppler WT, Basu P, Sheppard P, Choleris E, et al. (February 2018). "Female ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice are protected from the development of age-dependent cardiomyopathy". Cardiovascular Research. 114 (2): 259–271. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvx185. PMID 28927226.

- ^ Alibhai FJ, LaMarre J, Reitz CJ, Tsimakouridze EV, Kroetsch JT, Bolz SS, et al. (April 2017). "Disrupting the key circadian regulator CLOCK leads to age-dependent cardiovascular disease". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 105: 24–37. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.01.008. PMID 28223222.

- ^ Bennardo M, Alibhai F, Tsimakouridze E, Chinnappareddy N, Podobed P, Reitz C, et al. (December 2016). "Day-night dependence of gene expression and inflammatory responses in the remodeling murine heart post-myocardial infarction". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 311 (6): R1243 – R1254. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00200.2016. PMID 27733386. S2CID 36325095.

- ^ Pyle WG, Martino TA (October 2018). "Circadian rhythms influence cardiovascular disease differently in males and females: role of sex and gender". Current Opinion in Physiology. 5: 30–37. doi:10.1016/j.cophys.2018.05.003. ISSN 2468-8673. S2CID 80632426.

- ^ Rea MS, Figueiro M, Bullough J (May 2002). "Circadian photobiology: an emerging framework for lighting practice and research". Lighting Research & Technology. 34 (3): 177–187. doi:10.1191/1365782802lt057oa. S2CID 109776194.

- ^ Walmsley L, Hanna L, Mouland J, Martial F, West A, Smedley AR, et al. (April 2015). "Colour as a signal for entraining the mammalian circadian clock". PLOS Biology. 13 (4) e1002127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002127. PMC 4401556. PMID 25884537.

- ^ Hardt R (1970-01-01). "The Dangers of LED-Blue light-The Suppression of Melatonin-Resulting in-Insomnia-And Cancers | Robert Hardt". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-24.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bedrosian TA, Nelson RJ (January 2017). "Timing of light exposure affects mood and brain circuits". Translational Psychiatry. 7 (1): e1017. doi:10.1038/tp.2016.262. PMC 5299389. PMID 28140399.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Circadian Rhythm Disruption and Flying. FAA at https://www.faa.gov/pilots/safety/pilotsafetybrochures/media/Circadian_Rhythm.pdf Archived 2017-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Logan RW, Williams WP, McClung CA (June 2014). "Circadian rhythms and addiction: mechanistic insights and future directions". Behavioral Neuroscience. 128 (3): 387–412. doi:10.1037/a0036268. PMC 4041815. PMID 24731209.

- ^ Meyrel M, Rolland B, Geoffroy PA (20 April 2020). "Alterations in circadian rhythms following alcohol use: A systematic review". Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 99 109831. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109831. PMID 31809833.

- ^ Falcón E, McClung CA (2009-01-01). "A role for the circadian genes in drug addiction". Neuropharmacology. Frontiers in Addiction Research: Celebrating the 35th Anniversary of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. 56 (Suppl 1): 91–96. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.054. ISSN 0028-3908. PMC 2635341. PMID 18644396.

- ^ Prosser RA, Glass JD (June 2015). "Assessing ethanol's actions in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock using in vivo and in vitro approaches". Alcohol. 49 (4): 321–339. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.016. PMC 4402095. PMID 25457753.

- ^ "The science of jet lag". Timeshifter. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ Gold AK, Kinrys G (March 2019). "Treating Circadian Rhythm Disruption in Bipolar Disorder". Current Psychiatry Reports. 21 (3) 14. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1001-8. PMC 6812517. PMID 30826893.

- ^ Zhu L, Zee PC (November 2012). "Circadian rhythm sleep disorders". Neurologic Clinics. 30 (4): 1167–1191. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.011. PMC 3523094. PMID 23099133.

- ^ Crouse JJ, Carpenter JS, Song YJ, Hockey SJ, Naismith SL, Grunstein RR, et al. (September 2021). "Circadian rhythm sleep–wake disturbances and depression in young people: implications for prevention and early intervention". The Lancet Psychiatry. 8 (9): 813–823. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00034-1. PMID 34419186.

- ^ Scott J, Etain B, Miklowitz D, Crouse JJ, Carpenter J, Marwaha S, et al. (April 2022). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of sleep and circadian rhythms disturbances in individuals at high-risk of developing or with early onset of bipolar disorders". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 135 104585. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104585. PMC 8957543. PMID 35182537.

- ^ a b c Zelinski EL, Deibel SH, McDonald RJ (March 2014). "The trouble with circadian clock dysfunction: multiple deleterious effects on the brain and body". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 40 (40): 80–101. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.007. PMID 24468109. S2CID 6809964.

- ^ Oritz-Tuldela E, Martinez-Nicolas A, Diaz-Mardomingo C, Garcia-Herranz S, Pereda-Perez I, Valencia A, Peraita H, Venero C, Madrid J, Rol M. 2014. The Characterization of Biological Rhythms in Mild Cognitive Impairment. BioMed Research International.