Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gold rush

View on Wikipedia

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, Greece, Venezuela, New Zealand, Brazil, Chile, South Africa, the United States, and Canada while smaller gold rushes took place elsewhere.

In the 19th century, the wealth that resulted was distributed widely because of reduced migration costs and low barriers to entry. While gold mining itself proved unprofitable for most diggers and mine owners, some people made large fortunes, and merchants and transportation facilities made large profits. The resulting increase in the world's gold supply stimulated global trade and investment. Historians have written extensively about the mass migration, trade, colonization, and environmental history associated with gold rushes.[2]

Gold rushes were typically marked by a general buoyant feeling of a "free-for-all" in income mobility, in which any single individual might become abundantly wealthy almost instantly, as expressed in the California Dream.

Gold rushes helped spur waves of immigration that often led to the permanent settlement of new regions. Activities propelled by gold rushes define significant aspects of the culture of the Australian and North American frontiers. At a time when the world's money supply was based on gold, the newly-mined gold provided economic stimulus far beyond the goldfields, feeding into local and wider economic booms.

The Gold Rush was a topic that inspired many TV shows and books considering it was a very important topic at the time. During various gold rushes, many books were published including The Call of the Wild, which had much success during the period.

Gold rushes occurred as early as the times of ancient Greece, whose gold mining was described by Diodarus Sicules and Pliny the Elder.

Surviving the gold rush

[edit]

Within each mining rush there is typically a transition through progressively higher capital expenditures, larger organizations, and more specialized knowledge.

A rush typically begins with the discovery of placer gold made by an individual. At first the gold may be washed from the sand and gravel by individual miners with little training, using a gold pan or similar simple instrument. Once it is clear that the volume of gold-bearing sediment is larger than a few cubic metres, the placer miners will build rockers or sluice boxes, with which a small group can wash gold from the sediment many times faster than using gold pans. Winning the gold in this manner requires almost no capital investment, only a simple pan or equipment that may be built on the spot, and only simple organisation. The low investment, the high value per unit weight of gold, and the ability of gold dust and gold nuggets to serve as a medium of exchange, allow placer gold rushes to occur even in remote locations.

After the sluice-box stage, placer mining may become increasingly large scale, requiring larger organisations and higher capital expenditures. Small claims owned and mined by individuals may need to be merged into larger tracts. Difficult-to-reach placer deposits may be mined by tunnels. Water may be diverted by dams and canals to placer mine active river beds or to deliver water needed to wash dry placers. The more advanced techniques of ground sluicing, hydraulic mining and dredging may be used.

Typically the heyday of a placer gold rush would last only a few years. The free gold supply in stream beds would become depleted somewhat quickly, and the initial phase would be followed by prospecting for veins of lode gold that were the original source of the placer gold. Hard rock mining, like placer mining, may evolve from low capital investment and simple technology to progressively higher capital and technology. The surface outcrop of a gold-bearing vein may be oxidized, so that the gold occurs as native gold, and the ore needs only to be crushed and washed (free milling ore). The first miners may at first build a simple arrastra to crush their ore; later, they may build stamp mills to crush ore at greater speed. As the miners venture downwards, they may find that the deeper part of vein contains gold locked in sulfide or telluride minerals, which will require smelting. If the ore is still sufficiently rich, it may be worth shipping to a distant smelter (direct shipping ore). Lower-grade ore may require on-site treatment to either recover the gold or to produce a concentrate sufficiently rich for transport to the smelter. As the district turns to lower-grade ore, the mining may change from underground mining to large open-pit mining.

Many silver rushes followed upon gold rushes. As transportation and infrastructure improve, the focus may change progressively from gold to silver to base metals. In this way, Leadville, Colorado started as a placer gold discovery, achieved fame as a silver-mining district, then relied on lead and zinc in its later days. Butte, Montana began mining placer gold, then became a silver-mining district, then became for a time the world's largest copper producer.

By region

[edit]Australia and New Zealand

[edit]

Various gold rushes occurred in Australia over the second half of the 19th century. The most significant of these, although not the only ones, were the New South Wales gold rush and Victorian gold rush in 1851,[3] and the Western Australian gold rushes of the 1890s. They were highly significant to their respective colonies' political and economic development as they brought many immigrants, and promoted massive government spending on infrastructure to support the new arrivals who came looking for gold. While some found their fortune, those who did not often remained in the colonies and took advantage of extremely liberal land laws to take up farming.

Gold rushes happened at or around:

- Ballarat, Victoria

- Bathurst, New South Wales

- Beechworth, Victoria

- Bendigo, Victoria

- Canoona, Queensland

- Charters Towers, Queensland

- Coolgardie, Western Australia

- Gympie, Queensland

- Gulgong, New South Wales

- Halls Creek, Western Australia

- Hill End, New South Wales

- Kalgoorlie, Western Australia

- Queenstown, Tasmania

In New Zealand the Otago gold rush from 1861 attracted prospectors from the California gold rush and the Victorian gold rush and many moved on to the West Coast gold rush from 1864.

North America

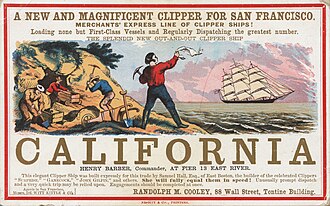

[edit]The first significant gold rush in the United States was in Cabarrus County, North Carolina (east of Charlotte), in 1799 at today's Reed's Gold Mine.[4] Thirty years later, in 1829, the Georgia Gold Rush in the southern Appalachians occurred. It was followed by the California Gold Rush of 1848–55 in the Sierra Nevada, which captured the popular imagination. The California Gold Rush led to an influx of gold miners and newfound gold wealth, which led to California's rapid industrialization, as businesses sprung up to serve the increased population and financial and political institutions to handle the increased wealth.[5] One of these political institutions was statehood; the need for new laws in a sparsely-governed land led to the state's rapid entry into the Union in 1850.[6]

The gold rush in 1849 also stimulated worldwide interest in prospecting for gold, leading to further rushes in Australia, South Africa, Wales and Scotland. Successive gold rushes occurred in western North America: Fraser Canyon, the Cariboo district and other parts of British Columbia, in Nevada, in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, eastern Oregon, and western New Mexico Territory and along the lower Colorado River. There was a gold rush in Nova Scotia (1861–1876) which produced nearly 210,000 ounces of gold.[7] Resurrection Creek, near Hope, Alaska was the site of Alaska's first gold rush in the mid–1890s.[8] Other notable Alaska Gold Rushes were Nome, Fairbanks, and the Fortymile River.

One of the last "great gold rushes" was the Klondike Gold Rush in the Yukon Territory (1896–99). This gold rush is featured in the novels of Jack London, and Charlie Chaplin's film The Gold Rush. Robert William Service depicted in his poetries the Gold Rush, especially in the book The Trail of '98.[9] The main goldfield was along the south flank of the Klondike River near its confluence with the Yukon River near what was to become Dawson City in Yukon Territory, but it also helped open up the relatively new US possession of Alaska to exploration and settlement, and promoted the discovery of other gold finds.

The most successful of the North American gold rushes was the Porcupine Gold Rush in Timmins, Ontario area. This gold rush was unique compared to others by the method of extraction of the gold. Placer mining techniques were not able to be used to access the gold in the area due to it being embedded into the Canadian Shield, so larger mining operations involving significantly more expensive equipment was required. While this gold rush peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, it is still active today with over 200 million[10] ounces of gold having been produced from the region. The gold deposits in this area are identified as one of the largest in the world.[11]

Africa

[edit]In South Africa, the Witwatersrand Gold Rush in the Transvaal was important to that country's history, leading to the founding of Johannesburg and tensions between the Boers and British settlers as well as the Chinese miners.[12]

South African gold production went from zero in 1886 to 23% of the total world output in 1896. At the time of the South African rush, gold production benefited from the newly discovered techniques by Scottish chemists, the MacArthur-Forrest process, of using potassium cyanide to extract gold from low-grade ore.[13]

South America and the Caribbean

[edit]

With the arrival of Nicolás de Ovando's settlement expedition in 1502, the construction of the first colonial society in the Hispaniola island began, focused on the search for and exploitation of gold of Cibao valley. The influx of immigrants was massive until 1510, when the island's gold production reached its peak. The mining industry rested on the forced work of the Taíno indigenous, who quickly became extinct. With the decline of the Taíno labor force and the depletion of deposits, gold production also declined, surpassing that of Puerto Rico and Cuba by the second decade of the century.[14]

The gold mine at El Callao (Venezuela), started in 1871, was for a time one of the richest in the world, and the goldfields as a whole saw over a million ounces exported between 1860 and 1883. The gold mining was dominated by immigrants from the British Isles and the British West Indies, giving an appearance of almost creating an English colony on Venezuelan territory.

Between 1883 and 1906 Tierra del Fuego experienced a gold rush attracting many Chileans, Argentines and Europeans to the archipelago. The gold rush began in 1884 following discovery of gold during the rescue of the French steamship Arctique near Cape Virgenes.[15]

Mining industry today

[edit]There are about 10 to 30 million small-scale miners around the world, according to Communities and Small-Scale Mining (CASM). Approximately 100 million people are directly or indirectly dependent on small-scale mining. For example, there are 800,000 to 1.5 million artisanal miners in Democratic Republic of Congo, 350,000 to 650,000 in Sierra Leone, and 150,000 to 250,000 in Ghana, with millions more across Africa.[16]

In an exclusive report, Reuters accounted the smuggling of billions of dollars' worth of gold out of Africa through the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East, which further acts as a gateway to the markets in the United States, Europe and more. The news agency evaluated the worth and magnitude of illegal gold trade occurring in African nations like Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia, by comparing the total gold imports recorded into the UAE with the exports affirmed by the African states. According to Africa's industrial mining firms, they have not exported any amount of gold to the UAE – confirming that the imports come from other, illegal sources. As per customs data, the UAE imported gold worth $15.1 billion from Africa in 2016, with a total weight of 446 tons, in variable degrees of purity. Much of the exports were not recorded in the African states, which means a huge volume of gold imports were carried out with no taxes paid to the states producing it.[17]

By date

[edit]Before 1860

[edit]- El Cibao valley at Hispaniola island (1494)

- Zacatecas Gold Rush, Viceroyalty of New Spain (1546)

- Parral, Chihuahua (1631)

- Brazilian Gold Rush, Minas Gerais (1695)[18]

- El Oro Gold Rush, El Oro de Hidalgo (1787)

- Carolina Gold Rush, Cabarrus County, North Carolina, US (1799)[4]

- Georgia Gold Rush, Georgia, US (1828)

- California Gold Rush (1848–55)

- Siberian Gold Rush, Siberia, Russian Empire (19th century)

- Queen Charlottes Gold Rush, British Columbia, Canada (1850); the first of many British Columbia gold rushes

- Northern Nevada Gold Rush (1850–1934)[clarification needed]

- Victorian gold rush, Victoria, Australia (1851–late 1860s). Known as the Golden Triangle, it incorporated areas such as Ararat, Castlemaine, Marybororgh, Clunes, Bendigo, Ballarat, Daylesford, Beechworth, and Eldorado.

- Kern River Gold Rush, California (1853–58)

- Idaho Gold Rush, near Colville, Washington (1855; also known as the Fort Colville Gold Rush)

- Gila Placers Rush, New Mexico Territory (present-day Arizona; 1858–59)

- Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, British Columbia (1858–61)

- Rock Creek Gold Rush, British Columbia (1859–60s)[clarification needed]

- Pike's Peak Gold Rush, Pikes Peak, Kansas Territory (present-day Colorado; 1859)

1860s

[edit]- Holcomb Valley Gold Rush, California (1860–61)

- Clearwater Gold Rush, Idaho (1860)

- Otago gold rush, New Zealand (1861)

- Eldorado Canyon Rush, New Mexico Territory (present-day Nevada; 1861)

- Colorado River Gold Rush, Arizona Territory (1862–64)

- Boise Basin Gold Rush, Idaho (1862)

- Cariboo Gold Rush, British Columbia (1862–65)

- Montana Gold Rush (1862–69), including:[19]

- Bannack, Virginia City (Alder Gulch), and Helena (Last Chance Gulch) (1862–64)

- Confederate Gulch (1864–69)

- Stikine Gold Rush, British Columbia (1863)

- Owyhee Gold Rush, Southeastern Oregon, Southwestern Idaho (1863)

- Owens Valley Rush, Owens Valley, California (1863–64)

- Leechtown Gold Rush, (south of Sooke Lake), Leech River, Vancouver Island (1864–65)

- West Coast gold rush, South Island, New Zealand (1864–67)

- Big Bend Gold Rush, British Columbia (1865–66)

- Francistown Gold Rush, British Protectorate of Bechuanaland (1867)[20]

- Omineca Gold Rush, British Columbia (1869)

- Wild Horse Creek Gold Rush, British Columbia (1860s)[clarification needed]

- Eastern Oregon Gold Rush (1860s–70s)[clarification needed]

- Kildonan Gold Rush, Sutherland, Scotland (1869)[21]

1870s

[edit]- Lapland gold rush, Finland, 1870

- El Callao Gold Rush, Venezuela, 1871

- Cassiar Gold Rush, British Columbia, 1871

- Palmer River Gold Rush, Palmer River, Queensland, Australia (1872)

- Pilgrim's Rest, South Africa (1873)

- Black Hills Gold Rush, Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming (1874–78)

- Bodie Gold Rush, Bodie, California (1876)

- Kumara Gold Rush, Kumara and Dillmanstown, New Zealand (1876)[22]

- Millwood, South Africa (1876)

1880s

[edit]- Barberton Gold Rush, South Africa (1883)

- Witwatersrand Gold Rush, Transvaal, South Africa (1886); discovery of the largest deposit of gold in the world. The resulting influx of miners became one of the triggers of the Second Boer War of 1899–1902.

- Cayoosh Gold Rush in Lillooet, British Columbia (1884–87)

- Tulameen Gold Rush, near Princeton, British Columbia[when?]

- Tierra del Fuego Gold Rush, southernmost Chile and Argentina (1884–1906)

- Baja California Gold Rush, in the Santa Clara mountains about sixty miles southeast of Ensenada (1889)[23]

- Amur gold rush, on the China-Russia border. Some miners in the region formed independent proto-states such as the Zheltuga Republic.

1890s

[edit]- Cripple Creek Gold Rush, Cripple Creek, Colorado (1891)

- Western Australian gold rushes, Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie, Western Australia (1893, 1896)

- Mount Baker Gold Rush, Whatcom County, Washington, United States (1897–1920s)

- Klondike Gold Rush, centered on Dawson City, Yukon, Canada (1896–99)

- Atlin Gold Rush, Atlin, British Columbia (1898)

- Nome Gold Rush, Nome, Alaska (1899–1909)

- Fairview Goldrush, Oliver (Fairview), British Columbia, Canada

20th century

[edit]- Fairbanks Gold Rush, Fairbanks, Alaska (1902–05)

- Goldfield Gold Rush, Goldfield, Nevada[when?]

- Porcupine Gold Rush, 1909–11, Timmins, Ontario, Canada – little known, but one of the largest in terms of gold mined, 67 million ounces as of 2001

- Iditarod Gold Rush, Flat, Alaska, 1910–12, where gold was discovered by John Beaton and William A. Dikeman in 1908

- Soviet gold rush - notably involving Gulag slave labor in the Kolyma region[24]

- Andacollo gold rush, Chile, 1932–1938[25]

- Kakamega gold rush, Kenya, 1932

- Vatukoula Gold Rush, Fiji, 1932

- Serra Pelada, Brazil

- Mount Diwata Gold Rush, Monkayo, Philippines, 1983–1987[26]

- Amazon Gold Rush, Amazon region, Brazil[when?][27]

- Mount Kare Gold Rush, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea[28][29]

21st century

[edit]- Great Mongolian Gold Rush, Mongolia (2001)[30]

- Bouaflé Gold Rush, Ivory Coast (2005)[31]

- Apuí Gold Rush, Apuí, Amazonas, Brazil (2006);[32] approximately 500,000 miners are thought to work in the Amazon's gold mines (Brazilian Portuguese: garimpos).[33]

- Peruvian Amazon gold rush, Madre de Dios (2009)[34]

- Tibesti Mountains gold rush, Chad, Libya and Niger (2012)[35]

- Djado Plateau Gold Rush, Ténéré Desert and Aïr Massif, Niger (2014)[36]

- Gold rush in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (2021)[37][38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ralph K. Andrist (2015). The Gold Rush. New Word City. p. 29. ISBN 978-1612308975.

- ^ Reeves, Keir; Frost, Lionel; Fahey, Charles (22 June 2010). "Integrating the Historiography of the Nineteenth-Century Gold Rushes". Australian Economic History Review. 50 (2): 111–128. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8446.2010.00296.x.

- ^ Wendy Lewis, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ^ a b "The North Carolina Gold Rush". Tar Heel Junior Historian 45, no. 2 (Spring 2006) copyright North Carolina Museum of History.

- ^ Nash, Gerald D. (1998). "A Veritable Revolution: The Global Economic Significance of the California Gold Rush". California History. 77 (4): 276–292. JSTOR 25462518.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- ^ "Gold Rushes: The First Gold Rush". Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Halloran, Jim (September 2010). "Alaska's Hope-Sunrise Mining District". Prospecting and Mining Journal. 80 (1). Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Biographie".

- ^ "The gold exploration surge continues in Timmins". 22 August 2022.

- ^ Turner, Bob; Quat, Marianne; Debicki, Ruth; Thurston, Phil (2015), "Timmins: Canada's greatest goldfields!" (PDF), Natural Resources Canada and Ontario Geological Survey 2015, GeoTours Northern Ontario series

- ^ Ngai, Mae M. (2021). The Chinese question : the gold rushes and global politics. New York. ISBN 978-0-393-63416-7. OCLC 1196176649.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Micheloud, François (2004). "The Crime of 1873: Gold Inflation this time". FX Micheloud Monetary History. François Micheloud: www.micheloud.com. Archived from the original on 2006-05-20.

- ^ Moya Pons, Frank. El oro en la historia dominicana. Primera edicion 1944. Series Academia Dominicana de la Historia. Academia Dominicana de la Historia. Santo Domingo, 2016.

- ^ Martinic Beros, Mateo. Crónica de las Tierras del Canal Beagle. 1973. Editorial Francisco de Aguirre S.A. pp. 55–65

- ^ Soaring prices drive a modern, illegal gold rush, New York Times, July 14, 2008

- ^ "Gold worth billions smuggled out of Africa". Reuters. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Gold rush". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- ^ Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. (1991). "Chapter 4, The Mining Frontier". Montana : a history of two centuries (Rev. ed.). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. pp. 64–91. ISBN 978-0-295-97129-2. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Murphy, Alan; Armstrong, Kate; Bainbridge, James; Firestone, Matthew D. (January 27, 2010). Southern Africa. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781740595452 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Baile an Or project– Scotland's Gold Rush Retrieved: 2010-03-31". Archived from the original on 2011-06-25. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ^ Dollimore, Edward Stewart. – "Kumara, Westland". – Encyclopedia of New Zealand (1966).

- ^ Flanigan, Sylvia K. (Winter 1980). Thomas L. Scharf (ed.). "The Baja California gold rush of 1889". The Journal of San Diego History. 26 (1). San Diego Historical Society Quarterly.

- ^

Levitan, Gregory (2008). "1: History of gold exploration and mining in the CIS". Gold Deposits Of The CIS. Xlibris Corporation. p. 24. ISBN 9781462836024. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

The early 1930s were marked by the decision of the Communist Party Politburo to reinstate the institution of prospectors who had been banned as antisocialist elements in the second half of the 1920s. Littlepage described in his book (1938) that by 1933 all plans to put prospectors back to work in the field had been worked out and implemented as rapidly as possible. Regulations to govern relations between prospectors and Gold Thrust were drawn up, setting in motion a Soviet gold rush.

- ^ Millán, Augusto (2006). La minería metálica en Chile en el siglo XX [Metal Mining in Chile in the Twentieth Century] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria. pp. 13–14. ISBN 956-11-1849-1.

- ^ Rationalizing Mining Operations at the Diwalwal Gold Rush Area, Monkayo, Compostela Valley

- ^ Marlise Simons (1988-04-25). "In Amazon Jungle, a Gold Rush Like None Before". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- ^ Henton, Dave, and Andi Flower. 2007. Mount Kare Gold Rush: Papua New Guinea 1988 – 1994. ISBN 978-0646482811.

- ^ Ryan, Peter. 1991. Black Bonanza: A Landslide of Gold. Hyland House. ISBN 978-0947062804.

- ^ Grainger David (December 22, 2003). "The Great Mongolian Gold Rush The land of Genghis Khan has the biggest mining find in a very long time. A visit to the core of a frenzy in the middle of nowhere". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ Yassin Ciyow (2021-07-06). "In Côte d'Ivoire, the precarious life of women gold prospectors". Le Monde.fr. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ Jens Glüsing (February 9, 2007). "Gold Rush in the Rainforest: Brazilians Flock to Seek their Fortunes in the Amazon". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ Tom Phillips (January 11, 2007). "Brazilian goldminers flock to 'new Eldorado'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ Lauren Keane (December 19, 2009). "Rising prices spark a new gold rush in Peruvian Amazon". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ Chamberlain, Gethin (January 17, 2018). "The deadly African gold rush fuelled by people smugglers' promises". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ Alissa Descotes-Toyosaki (2 April 2018). "Niger: the gold rush". Paris Match. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "In Congo's gold rush, the money is in beer and brothels". The Economist. 2020-12-19. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ "Congo bans mining in South Kivu village after gold rush". Reuters. 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

Further reading

[edit]- Ngai, Mae. The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics (2021), Mid 19c in California, Australia and South Africa [ISBN missing]

- White, Franklin. Miner with a Heart of Gold – Biography of a Mineral Science and Engineering Educator. FriesenPress. 2020. ISBN 978-1-5255-7765-9 (Hardcover) ISBN 978-1-5255-7766-6 (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-5255-7767-3 (eBook).

External links

[edit]- Object of History: the Gold Nugget

- PBS' American Experience: The Gold Rush

- Exploring the California Gold Rush

- The Australian Gold Rush

- Off to the Klondike! The Search for Gold Archived 2016-04-02 at the Wayback Machine – illustrated historical essay

Gold rush

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Elements of a Gold Rush

A gold rush refers to the sudden and large-scale migration of prospectors to a region following the discovery of accessible gold deposits, typically in placer or alluvial formations that permit extraction through rudimentary techniques. This phenomenon is initiated by a verifiable find, often by an individual or small group, which disseminates via reports, letters, or newspapers, creating a feedback loop of anticipation and movement. Unlike planned economic ventures, gold rushes embody speculative behavior where participants weigh the high variance of outcomes—potential riches against failure rates exceeding 90% for most claimants—driven by gold's intrinsic value as a store of wealth and medium of exchange.[5][6] Central to gold rushes is the dominance of short-term placer mining, involving methods like panning, sluicing, and rocking to separate gold from loose sediments using water and gravity, which contrasts sharply with sustained lode mining of quartz veins requiring capital, machinery, and engineering for deep extraction. These initial phases exploit surface-level accumulations formed by erosion, yielding quick but finite returns that deplete within months to years, fostering boom-bust cycles rather than enduring operations. Empirical observations indicate temporary population surges in remote locales, transforming sparse outposts into tent cities with service economies for supplies, gambling, and vice, before abandonment as easy gold vanishes.[7][8][9] The primary causal mechanisms stem from individual risk-taking in response to market signals of untapped opportunity, where gold's scarcity and universal demand incentivize relocation over stable livelihoods, independent of governmental promotion or subsidies. This decentralized dynamic relies on personal initiative and information asymmetry resolution through rumor and verification, underscoring how fortune-seeking aligns with human incentives under conditions of high-reward uncertainty, rather than collective or institutional direction.[5][10]Economic Drivers and Migration Dynamics

The primary economic driver of gold rushes was the prospect of extraordinarily high returns to individual labor during the initial discovery and extraction phases, where accessible placer deposits allowed early prospectors to recover significant quantities of gold using basic tools like pans and rockers, often yielding daily outputs valued at multiples of prevailing wages elsewhere. In the California Gold Rush's opening months of 1848, for example, prospectors at Sutter's Mill and nearby sites extracted gold at rates equivalent to $20 per day—ten to twenty times the $1 daily wage typical for unskilled labor in the eastern United States—creating a stark gold-to-labor value ratio that attracted profit-seeking migrants ranging from farmers and merchants to professionals willing to forgo stable employment for high-variance opportunities.[11] This incentive structure operated on first-principles of marginal productivity: untapped alluvial deposits minimized upfront capital needs, enabling even low-skilled entrants to capture rents until competition eroded yields. Migration dynamics amplified these drivers through rapid, decentralized dissemination of information, which exploited asymmetries between exaggerated reports of easy riches and the actual stochastic nature of finds, generating self-reinforcing speculative fervor without orchestrated coordination. News of the 1848 California discovery propagated initially via word-of-mouth among local traders and Mormon Battalion members, then accelerated through letters to family and early San Francisco newspapers like the Californian, reaching eastern U.S. audiences by December 1848 and igniting transcontinental movements.[12] Transport costs, ranging from $100–$300 for sea passages via Panama or Cape Horn to $400 for overland wagon trains in 1849, represented 3–12 months' equivalent wages for many migrants yet proved surmountable given perceived expected values, drawing over 40,000 arrivals by year's end and peaking at 300,000 by 1852—a pattern replicated in Australian and Klondike rushes where similar hype via global telegraph and press outpaced verification of deposit sustainability.[13] Despite initial allure, empirical failure rates underscored the selective pressures of these dynamics, with most migrants confronting diminishing returns as claims crowded and surface gold depleted, resulting in estimates that fewer than half achieved even modest net profits after expenses, and sustained profitability confined to a small entrepreneurial subset adept at adaptation or diversification into supply trades.[14] This <10% success threshold for significant wealth accumulation, derived from post-rush censuses and diaries revealing widespread abandonment or penury, highlighted how information lags and overoptimism propelled oversupply, filtering for resilient operators while imposing high personal costs on the majority.[3] Such uncoordinated influxes, driven purely by individual arbitrage of yield differentials, exemplify causal mechanisms of boom-bust cycles in extractive frontiers.Historical Overview

Pre-19th Century Gold Rushes

One of the earliest instances resembling a gold rush occurred in the Roman Empire's exploitation of Dacia following its conquest by Emperor Trajan between 101 and 106 AD, where gold deposits at sites like Alburnus Maior (modern Roșia Montană, Romania) drew organized mining efforts yielding significant output through hydraulic techniques and slave labor, though production was state-controlled rather than driven by individual prospectors.[15] Similarly, in northwestern Spain's Las Médulas region during the 1st century AD, Romans engineered vast open-pit operations using water channels to extract an estimated 20 million cubic meters of sediment, producing up to 3 tons of gold annually in peak years, marking one of the first large-scale rushes fueled by imperial expansion and technological innovation like ruina montium collapse methods, but limited by reliance on manual labor and rudimentary tools.[16] These efforts highlighted localized economic booms, with gold funding military campaigns, yet constrained by the absence of mechanization, leading to environmental devastation and eventual depletion without widespread migration akin to later events. In colonial Brazil, the discovery of alluvial gold in the interior highlands of Minas Gerais in the 1690s triggered the Portuguese Empire's first major gold rush, beginning with bandeirante expeditions in 1693 that uncovered payable deposits, attracting thousands of prospectors and slaves from coastal settlements and Portugal, resulting in annual production exceeding 10 tons by the 1720s through panning and basic sluicing.[16] This rush, peaking around 1750, extracted over 800 tons of gold in total from the colony, stimulating urban growth in areas like Ouro Preto but burdened by royal fifths taxation (20% levy) and primitive techniques that favored surface deposits, often exhausting fields within decades due to flooding and erosion without deeper shaft capabilities.[17] Localized impacts included social upheaval from enslaved African labor and conflicts with indigenous groups, setting patterns of boom-and-bust cycles under colonial oversight. In North America, the 1799 discovery at Reed Gold Mine in Cabarrus County, North Carolina, by 12-year-old Conrad Reed, who found a 17-pound nugget in Little Meadow Creek, initiated the first documented U.S. gold find, prompting small-scale placer mining that spread to adjacent counties and produced modest yields—totaling about 100,000 ounces over decades—using simple tools like rockers and pans amid technological limits that prevented large operations until steam power later.[18] This event spurred early American interest in domestic gold, with John Reed's family developing the site into a rudimentary mine by 1803, but output remained localized due to shallow veins and lack of capital, influencing state geology surveys without triggering mass migration.[19] These pre-19th century examples underscore rushes as regionally confined phenomena, dependent on surface discoveries and constrained by pre-industrial methods, foreshadowing the scale enabled by later advancements.Mid-19th Century North American and Australian Rushes

The California Gold Rush commenced on January 24, 1848, following James W. Marshall's discovery of gold flakes at Sutter's Mill on the South Fork of the American River in Coloma, California, while constructing a sawmill for landowner John Sutter. [20] News spread rapidly via newspapers and returning miners, igniting a migration frenzy that drew approximately 80,000 arrivals in 1849 alone and swelled to an estimated 300,000 by 1852, primarily young men from the United States, Europe, Latin America, and China seeking placer deposits amenable to rudimentary panning and sluicing. [3] Production peaked in 1852 at roughly $81 million in gold value, equivalent to about 3.9 million troy ounces, before declining as surface deposits depleted; cumulatively, the rush yielded around $2 billion in gold at period prices through 1855.[21] This surge not only flooded local economies with liquidity but accelerated California's admission as the 31st U.S. state on September 9, 1850, amid the population boom that transformed a remote territory into a viable polity. Inspired in part by California reports and prospectors who relocated southward, Australia's Victorian Gold Rush ignited in mid-1851 with major finds at Ballarat and Bendigo in the Port Phillip District (later Victoria), following earlier minor discoveries in New South Wales.[22] The colonial government issued miner's licenses—initially £30 per month, later reduced—to regulate access, applying uniformly to British subjects and immigrants alike, which fostered initial egalitarian access to claims but sparked resentment over fees and arbitrary enforcement, culminating in events like the 1854 Eureka Stockade.[23] Victoria's population exploded from 76,000 in 1851 to over 540,000 by 1860, part of Australia's broader quadrupling from 430,000 to 1.7 million between 1851 and 1871, fueled by migrants from Britain, Europe, China, and even California veterans.[22] [23] Yields were prodigious, with Victoria extracting hundreds of tons annually in peak years, contributing over £87 million in gold from 1851 to 1860 and accounting for more than one-third of Australia's lifetime output of approximately 2,400 tonnes.[24] These contemporaneous rushes—California's from 1848-1855 and Victoria's peaking through the 1850s—collectively amplified global gold production, with the two regions supplying over 40% of world output in the decade, effectively doubling available stocks from pre-rush levels of around 200-300 tonnes annually.[25] This influx constituted a positive monetary shock under prevailing bimetallic and gold standards, expanding circulating specie to match industrial-era growth without inducing hyperinflation, as absorption into expanding economies mitigated price spikes; for instance, U.S. wholesale prices rose modestly before stabilizing.[25] Causal linkages included trans-Pacific knowledge diffusion, where California's validated placer techniques and tales of nuggets encouraged Australian exploration, while both booms stemmed from geological alluvial concentrations overlooked amid prior colonial underpopulation.[22]Late 19th Century Global Rushes

The late 19th century saw gold rushes extend into increasingly remote and inhospitable regions, as accessible placer deposits in earlier fields dwindled, compelling prospectors to adapt to extreme climates and more labor-intensive extraction in areas like the subarctic Yukon and arid South African reefs.[26] These migrations, peaking between 1886 and 1899, involved tens of thousands drawn by reports of rich strikes, but yields often proved fleeting, underscoring the finite nature of surface gold and the need for technological shifts toward mechanized recovery.[27] The Klondike Gold Rush, ignited by the August 1896 discovery on Bonanza Creek in Canada's Yukon Territory, exemplifies this push into subarctic frontiers. An estimated 100,000 prospectors departed for the region by 1897, though only about 30,000 reached the fields after enduring grueling overland treks, including the 1,000-meter Chilkoot Pass ascent amid avalanches and sub-zero temperatures that claimed hundreds of lives. Initial annual outputs reached $14 million in 1899, contributing to a rush total of nearly $29 million by 1900, primarily from placer mining via sluices and rockers under frozen ground conditions requiring winter thawing fires.[28][29][30] These harsh exigencies spurred early innovations like steam-powered dredges for riverbed processing, though easy nuggets depleted rapidly, forcing many to abandon claims by 1900.[31] In South Africa, the 1886 Witwatersrand discovery marked a pivot from alluvial to deep-vein reef mining, transforming Johannesburg from a tent camp into an industrial hub by 1890. Unlike prior surface rushes, gold here lay in quartz conglomerates up to 2 kilometers deep, necessitating cyanide leaching and steam-driven hoists that by 1898 surpassed U.S. output, capturing 23% of global production that year and fueling British imperial finance through exports funding wars and railways.[32][33] Production scaled to dominate 25% of world supply by 1900, but at the cost of exploitative labor systems importing 100,000+ migrant workers annually under compound conditions, highlighting the rush's role in entrenching economic inequalities rather than widespread individual fortunes.[34][35] New Zealand's Otago fields, initially rushed in 1861, experienced late-19th-century revivals around 1890 via hydraulic sluicing and bucket dredges that reworked exhausted gravels, yielding secondary booms despite primary placer depletion. Annual output, which had peaked at over 17,000 kilograms (about 560,000 ounces) in 1863, fell to sustained but lower levels of several thousand ounces per major operation by the 1890s, as dredges processed vast tailings but faced rapid resource exhaustion and environmental scarring of river valleys.[36][37] This trajectory illustrated the limits of technological adaptation to finite deposits, with total Otago gold nearing 4 million ounces by century's end, prompting diversification into quartz crushing amid declining yields.[38][39]20th and 21st Century Developments

In the twentieth century, gold mining transitioned from episodic rushes characterized by individual prospectors to systematic industrial operations, with cyanide leaching—initially commercialized in the late 1890s—enabling the viable recovery of gold from low-grade sulfide ores previously uneconomical. This process, involving the dissolution of gold in a cyanide solution followed by precipitation, facilitated sustained output from mature deposits rather than reliance on new bonanzas. In Alaska, post-Klondike activities extended into the early 1900s through placer dredging in regions like the Nome and Fairbanks districts, maintaining production amid declining surface deposits but without the mass migrations of prior decades.[40][41] By the mid-twentieth century, corporate entities increasingly dominated, employing heap leaching variants of cyanidation to reprocess tailings and expand from hardrock sources, further diminishing the prospect of classic rushes as regulatory frameworks and capital requirements favored established firms over solo ventures. This era marked a stabilization in North American production, with Alaska's output peaking in the 1930s before wartime demands and post-war mechanization supported consistent yields into the 1950s and beyond.[42] The twenty-first century has seen no equivalents to nineteenth-century mass migrations, as large-scale corporate mining—accounting for the bulk of output—preempted disorganized influxes through advanced exploration and permitting. Global mine production hovered around 3,600 tonnes annually in the early 2020s, with China, Russia, and Australia leading via industrial complexes rather than artisanal scrambles.[43][44] Elevated gold prices, exceeding $2,700 per ounce in 2024 and climbing further into 2025 amid geopolitical tensions and inflation, instead boosted informal artisanal mining in poverty-stricken areas like northwest Tanzania, where booms since the 2000s drove localized urbanization and labor shifts without broader migrations. Similar expansions occurred in Peru and parts of sub-Saharan Africa, often unregulated and environmentally taxing, contributing 10-20% of global supply but framed by experts as livelihood responses rather than speculative frenzies. In developed nations such as the United States, high prices prompted increased scrap recycling and jewelry liquidation over new prospecting, underscoring the era's emphasis on secondary markets.[45][46][47]Mining Methods and Technological Advances

Placer and Alluvial Techniques

Placer mining extracts gold from loose, unconsolidated alluvial deposits such as river gravels and sandbars, where heavy gold particles have accumulated due to gravity separation from lighter sediments over geological time.[48] These methods exploit the high density of gold (19.3 g/cm³) compared to surrounding materials (typically 2.6-2.7 g/cm³ for quartz), allowing separation via water flow and agitation without crushing ore.[49] Early techniques required minimal equipment and enabled rapid exploitation by inexperienced prospectors, contributing to the explosive initial phases of gold rushes. The simplest method, gold panning, involves swirling sediment-water mixtures in a shallow metal pan to wash away lighter materials, leaving heavier gold concentrates at the bottom.[50] Skilled panners could process several cubic feet of gravel daily, yielding fractions of an ounce in productive areas, though averages were often lower due to variable deposit richness.[7] More efficient devices like the rocker box—a wooden cradle with riffles—combined manual shoveling with rocking motion to agitate larger volumes (up to 1-2 cubic yards per day), improving throughput while still relying on gravity.[7] Sluice boxes extended this principle, using long wooden troughs (10-50 feet) with transverse riffles and continuous water flow to trap gold flakes and nuggets as sediment passed over.[51] Recovery efficiencies in these early methods were limited, often capturing no more than 60% of available gold, with significant losses of fine particles ("flour gold") that escaped riffles and flowed away with tailings.[49] Success depended critically on sediment characteristics, such as loose, permeable gravels that allowed easy digging and gold liberation, and reliable water access for washing—factors that determined workable sites near streams or with diverted flows.[48] In water-scarce areas, dry washing variants sifted material by wind or manual beating, but yields dropped sharply without hydraulic aid.[52] These techniques' low entry barriers—requiring only basic tools and physical labor—drove mass participation in rushes, allowing non-experts to test claims quickly and fueling rapid migration.[53] However, surface placers typically exhausted within 2-5 years as accessible deposits were depleted, shifting focus to deeper or harder materials.[7]Transition to Industrial Extraction

As placer deposits in regions like California and Australia began to deplete by the mid-1850s, miners turned to more capital-intensive techniques to access deeper or harder gold-bearing materials, marking the shift toward industrial extraction. Hydraulic mining, pioneered in California's Sierra Nevada foothills around 1853, utilized high-pressure water cannons—known as "monitors"—to erode entire hillsides and dislodge gravel containing gold particles, channeling the resulting slurry through sluices for separation.[54] This method dramatically boosted productivity compared to manual panning or rocker boxes, allowing operations to process vast volumes of material that individual prospectors could not handle, though exact multiples varied by site conditions.[55] The technique's efficiency stemmed from engineering innovations like iron nozzles and pressurized water systems derived from local ditches and flumes, but it generated massive silt loads that clogged downstream rivers and farmlands, prompting legal challenges. In 1884, the U.S. Circuit Court ruling in Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company—known as the Sawyer Decision—effectively banned unregulated hydraulic mining in California by holding companies liable for debris damage, halting widespread use despite its prior dominance in counties such as Nevada and Placer.[56] [55] This restriction accelerated exploration of lode deposits, where gold was embedded in quartz veins requiring crushing and chemical processing. By the 1890s, further mechanization emerged with steam-powered dredges for reworking river gravels and tailings piles, alongside the cyanide leaching process, which dissolved gold from low-grade ores using dilute sodium cyanide solutions followed by precipitation, achieving recovery rates up to 96 percent where amalgamation had failed.[57] First commercially applied in 1890 at the Randfontein mine on South Africa's Witwatersrand reef, cyanide enabled profitable extraction from refractory ores, complementing stamp mills that crushed up to several tons of quartz per hour per battery.[57] These advancements, driven by depleting surface resources and fixed gold prices around $20 per ounce, leveraged economies of scale—through larger equipment and centralized operations—to lower per-ounce extraction costs from labor-intensive highs exceeding $10 in early rushes to under $5 by the early 20th century in major districts.[7]Socio-Economic Impacts

Wealth Generation and Market Effects

The California Gold Rush produced gold valued at $550 million from 1848 to 1857, representing approximately 1.8% of U.S. gross domestic product during that decade.[58] This output averaged around 76 tons annually in the peak years, dwarfing prior U.S. production and injecting liquidity into a gold-standard economy previously strained by shortages.[58] The resulting monetary expansion drove a 30% rise in wholesale prices between 1850 and 1855, countering deflationary trends and bolstering gold's viability against bimetallic alternatives by increasing global supplies and stabilizing exchange ratios.[58] Economic multipliers amplified direct gold values, as heightened demand spurred ancillary sectors; real wages in California surged 515% from late 1847 to 1849 and remained four times national levels by 1860, fostering capital accumulation that indirectly supported national infrastructure like the transcontinental railroad completed in 1869.[58][58] Such gains refute zero-sum interpretations, as the rush integrated peripheral regions into core markets, elevating overall productivity rather than merely redistributing existing wealth. In Australia, Victorian gold fields yielded over a third of global output in the 1850s, displacing wool as the colony's top export until the 1870s and driving exports from New South Wales and Victoria up sixfold within three years of 1851 discoveries.[59][60] Mining accounted for 35% of GDP in 1852, with sustained contributions of 17.5% by 1861, financing infrastructure booms—including Victorian road expenditures jumping from £11,000 in 1851 to £520,000 in 1853 via London borrowing enabled by gold revenues—and wage increases of 250% from 1850 to 1853.[60][60][60] These per capita wealth elevations, alongside export-led growth, demonstrate net positive legacies, as resource windfalls diversified into urban and transport investments without derailing long-term productivity. Across rushes, empirical outcomes favored adaptive innovators over passive prospectors; while most migrants yielded modest or negative returns, high-variance payoffs—concentrated in early entrants and suppliers of tools, claims, and logistics—mirrored risk-adjusted incentives akin to proto-venture financing, channeling human capital toward scalable enterprises and countering narratives of systemic waste through verifiable GDP uplifts and monetary stabilization.[59][58]Infrastructure and Urban Development

The California Gold Rush prompted swift infrastructure enhancements centered on San Francisco as the chief entry port, where private merchants constructed wharves and warehouses to manage arriving steamships laden with provisions for miners. Wagon roads and stagecoach routes proliferated through entrepreneurial efforts to link the city to Sierra Nevada diggings, forming a foundational transportation web that endured beyond placer mining's decline.[61][62] By 1856, the Sacramento Valley Railroad commenced operations as California's inaugural rail line, spanning 22 miles from Sacramento to Folsom and easing goods transport to gold districts, with subsequent telegraph lines—completed to San Francisco by 1861—accelerating communications for supply coordination. These developments, largely financed by private capital responding to mining demands, outstripped governmental initiatives in speed and scope, establishing supply chains exemplified by Levi Strauss & Co.'s 1853 founding to outfit prospectors with durable textiles.[63][64] In Australia, the Victorian gold rush from 1851 fueled Melbourne's expansion as a logistics hub, with port facilities upgraded to handle migrant ships and exports, while roads radiated to fields like Ballarat, which evolved from tent camps into a sustained urban center boasting brick buildings and rail connections by the 1860s. Victoria's populace escalated from 77,345 in 1851 to 538,628 by 1861, underwriting permanent networks that integrated rural mines with coastal trade.[65] Later rushes yielded enduring outposts, such as Juneau, Alaska, established in 1880 amid coastal gold strikes and persisting as the state capital with developed harbors and roads supporting ongoing resource extraction. These cases illustrate how gold influxes spurred verifiable, investor-driven builds—roads, rails, and ports—that transitioned transient booms into lasting economic frameworks, often via private ventures prioritizing profitability over public delay.[66]Labor, Immigration, and Class Dynamics

The California Gold Rush drew a diverse influx of laborers, with foreign-born individuals comprising a significant portion of the population; by 1852, approximately 20,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived, representing about 30% of that year's arrivals amid a total influx of 67,000 people.[67] Overall, immigrants from Europe, Latin America, and Asia formed key segments of the workforce, including Europeans such as Irish and Germans alongside Chinese miners who at their peak accounted for up to 25% of mining labor in certain regions.[68] This diversity stemmed from global news of gold discoveries, prompting migrations driven by economic opportunity rather than state sponsorship. Wage premiums were substantial initially, with gold miners earning $8 to $20 per day in 1849-1850, compared to $1 to $3 daily for unskilled or skilled laborers in the eastern United States.[69][70] These rates, often 5 to 10 times higher, reflected acute labor shortages in the remote frontier, incentivizing rapid inflows and enabling short-term accumulations of wealth for efficient workers.[71] Class structures exhibited notable fluidity, as the absence of entrenched hierarchies allowed merit-based advancement; many laborers transitioned from mining to mercantile roles by leveraging skills in trade or organization, with literacy and adaptability correlating positively with migration success and subsequent prosperity.[72] Empirical patterns indicate that while most individual miners realized limited net gains due to high costs and risks, a subset—estimated at 20-30% based on occupational shifts—achieved upward mobility through entrepreneurial pivots, underscoring the role of personal capability over inherited status.[14] As competition intensified post-1850, labor market dynamics eroded these premiums, with daily wages declining to around $10 by 1850 and further amid oversupply, effectively selecting for persistent, skilled participants while marginalizing less adaptable ones.[73] This process aligned with supply-driven equilibrium, where influxes of labor integrated California wages toward national levels, fostering a more stratified yet still relatively open system compared to rigid eastern economies.[71]Social and Cultural Dimensions

Demographic Shifts and Community Formation

The California Gold Rush initiated a predominantly male migration, with the 1850 U.S. census documenting that women comprised only 8% of the non-Indian population totaling 92,597 individuals.[74] This extreme gender imbalance, estimated at roughly 12 men per woman in the immediate aftermath of the 1848 discovery, resulted in transient, single-sex communities characterized by makeshift mining camps rather than settled family units.[75] Such demographics precluded stable social structures, leading to reliance on informal gathering spots like saloons for camaraderie, dispute resolution, and basic social functions among the overwhelmingly young, unmarried male prospectors. By the mid-1850s, as initial placer deposits waned, chain migrations brought increasing numbers of families and women, gradually moderating the sex ratio and enabling more permanent community formation.[75] The state's population surged to 379,994 by the 1860 census, reflecting a more than 300% increase from 1850 and incorporating diverse ethnic groups that contributed to emerging voluntary associations.[76] These shifts stabilized regions like San Francisco, where the population exploded from 812 in 1848 to 25,000 by 1850, fostering rudimentary institutions such as multidenominational churches that served as hubs for moral guidance and social cohesion amid the chaos.[77] Similar patterns emerged in other rushes, such as Australia's Victorian fields, where initial male-heavy influxes from 1851 yielded rapid urbanization but delayed family-based settlements until the late 1850s, promoting ad-hoc networks over enduring kinship ties. In these contexts, census-equivalent records highlight how skewed demographics initially hindered conventional community bonds, only yielding to stabilization as economic realities prompted broader migrations.[2]Interactions with Indigenous Peoples

The indigenous population of California, estimated at approximately 310,000 prior to Spanish colonization, had declined to around 150,000 by 1848 due to diseases introduced by European contact, harsh labor conditions, and high mortality rates in the mission system established from 1769 onward, with about one-third of the losses attributable directly to mission-era factors including epidemics of measles, syphilis, and influenza to which natives lacked immunity.[78][79] The Gold Rush accelerated this demographic collapse, reducing the population to roughly 30,000 by 1870 through a combination of renewed disease outbreaks from transient miners, habitat disruption from placer mining that destroyed traditional foraging areas like oak groves and salmon streams, and direct competition for resources leading to starvation.[80][79] Interactions varied by region and group, with some indigenous individuals and bands engaging in trade for goods like blankets and tools in exchange for labor or information on gold deposits, and occasionally prospecting alongside miners using traditional digging techniques; for instance, tribes such as the Miwok and Ohlone provided workforce support in early camps, reflecting pragmatic economic adaptations amid encroachment.[81] However, mutual alliances were limited, as mining claims rapidly formalized under norms of first discovery and continuous occupancy, enabling settlers to stake unclaimed lands—territories not enclosed, titled, or intensively cultivated by natives—without prior negotiation, consistent with international precedents for unoccupied domains under effective control.[82][83] Violence intensified conflicts, particularly from 1849 to 1855, as miners targeted native villages in retaliatory raids over thefts or competition, with state-legislated militias expending over $1.5 million in bounties and expeditions that killed thousands, though empirical tallies of direct fatalities remain imprecise amid overlapping causes like exposure and displacement.[80][83] These encounters stemmed causally from resource scarcity in contested watersheds, where native seasonal use yielded to permanent settler extraction, rather than systematic extermination policies, as evidenced by surviving populations' relocation to fringes rather than total eradication.[79][78]Governance, Law, and Vigilantism

In the absence of formal government following the 1848 gold discovery, California miners rapidly established self-governing associations to regulate claims and resolve disputes. These groups convened meetings to adopt mining codes that defined claim sizes—typically 16 feet square for individual placer operations—required marking and recording of claims, and mandated continuous labor to retain rights, preventing abandonment or speculation.[84] Such rules emerged organically in mining districts, enforcing property norms through peer consensus and occasional expulsion of violators, fostering order amid the influx of tens of thousands without state oversight.[85] Vigilante committees supplemented these codes by addressing rampant crime, including arson, robbery, and murder, which surged with population growth. In San Francisco, the 1851 Committee of Vigilance, formed in response to gangs like the Sydney Ducks, arrested hundreds, tried dozens, hanged four, and banished over 1,000 perceived criminals, thereby restoring public confidence and curbing lawlessness until formal institutions strengthened post-statehood in 1850.[86] Similar committees operated in mining camps, conducting trials and executions that paralleled judicial processes, evolving into precedents for codified law as territorial authorities formalized miner customs into statutes by the mid-1850s.[87] Challenges arose from state interventions, such as the 1850 Foreign Miners' Tax, which imposed a $20 monthly fee on non-citizens, prompting protests and localized violence, including expulsions of Mexican and Chilean miners in southern districts.[88] Despite such tensions, which led to tax revisions exempting certain white foreigners, the era's private enforcement mechanisms laid enduring foundations for rule-of-law principles, prioritizing productive claims and community stability over centralized fiat.[82]Environmental Effects

Short-Term Habitat and Resource Alterations

Hydraulic mining during the California Gold Rush profoundly altered local hydrology and geomorphology by blasting hillsides with high-pressure water jets, displacing vast quantities of overburden. This technique mobilized approximately 1.5 billion cubic yards of soil, gravel, and rock, which was sluiced for gold and dumped into waterways, causing riverbeds to aggrade and channels to shift.[89] Downstream, the sediment load triggered recurrent flooding, as seen in the Yuba and Feather Rivers, where deposits raised riverbeds by tens of feet and inundated farmland in the Sacramento Valley during the 1860s and 1870s.[90] To support these operations, extensive timber was harvested for flumes, sluices, and structural supports, leading to widespread deforestation in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Logging from 1850 onward cleared over 1.3 million acres in the northern Sierra by 1902, with much of the early activity tied to mining infrastructure rather than commercial lumber.[91] Denuded slopes accelerated soil erosion, funneling additional sediment into streams and amplifying habitat disruption from mining debris. Aquatic ecosystems suffered immediate biodiversity losses from siltation, which smothered benthic habitats and spawning gravels essential for fish reproduction. In affected Sierra streams, salmon and trout populations declined sharply due to egg suffocation and reduced water quality, with historical records indicating near-elimination of viable runs in heavily mined drainages by the late 1850s.[92] These changes were localized to mining districts, sparing upstream or remote tributaries, but demonstrated clear causal links between extraction intensity and short-term ecological impairment.[92]Persistent Pollution and Ecosystem Recovery

During the California Gold Rush, miners employed mercury amalgamation to extract gold from placer deposits and tailings, releasing an estimated 10 million pounds of mercury into the environment through losses of 10 to 30 percent per processing season.[93] This legacy contamination persists in Sierra Nevada watersheds, where methylation of inorganic mercury by anaerobic bacteria in sediments converts it to bioavailable methylmercury, leading to elevated concentrations in fish tissues exceeding safe consumption thresholds (e.g., >0.3 ppm in trout from streams like the South Yuba River).[94] Similar patterns occurred in other rushes, such as the Klondike, where pre-1925 hand-mining sites retain mercury residues detectable in tree rings and sediments from amalgamation practices.[96][40] Despite persistence in sediments and aquatic biota, empirical evidence indicates partial ecosystem recovery in many abandoned sites once anthropogenic disturbance ceased. In alluvial gold mining areas, natural revegetation through spontaneous succession has recolonized disturbed landscapes adjacent to intact native vegetation, with soil stabilization and plant cover restoring hydrological functions over decades.[97] Yukon rivers affected by Klondike-era placer mining, including mercury-impacted tributaries, exhibited improved water quality and benthic habitats post-1900 as claim abandonment reduced sediment inputs, enabling macroinvertebrate and fish populations to rebound without extensive intervention.[92] Contemporary remediation leverages biological methods to accelerate mitigation, countering claims of irreversible damage. Phytoremediation trials at legacy sites, including those with mercury from historical gold processing, demonstrate plant uptake and microbial volatilization reducing soil concentrations by up to 50 percent in field applications during the 2020s.[98][99] Market-driven efforts, such as private landowner initiatives and voluntary cleanups, have addressed hotspots (e.g., Alaska's Coal Creek project removing contaminated tailings in the 1990s), with costs often internalized via property value incentives rather than solely externalized.[100] These approaches, informed by USGS monitoring, show that while bioaccumulation risks endure in high-sediment zones, proactive and natural processes enable functional recovery without perpetual ecological collapse.[101]Controversies and Critical Perspectives

Debunking Romanticized Myths

The notion of gold rushes as egalitarian lotteries offering easy wealth to any determined prospector persists in popular culture, yet empirical evidence from participant records and economic analyses contradicts this. In the California Gold Rush, the archetypal event attracting over 300,000 migrants between 1848 and 1855, individual miners typically realized small or negative returns after accounting for travel costs, equipment, and living expenses, which often exceeded $1,000 per person in 1849 dollars.[72] Success was rare, with fortunes instead accruing disproportionately to merchants supplying goods at inflated prices—such as Levi Strauss with denim trousers or Samuel Brannan via wholesale—rather than to claim holders panning streams.[25] Miners' diaries and census data further underscore the disparity: many, including professionals like doctors and lawyers who abandoned stable careers, extracted mere ounces daily after initial surface deposits depleted by 1850, yielding insufficient to offset hardships like scurvy, violence, and claim disputes. By 1852, when annual gold output peaked at approximately 3 million ounces before declining, over half of arrivals had departed penniless, turning to farming, ranching, or wage labor in emerging cities like San Francisco.[102] This pattern repeated in later rushes, such as the 1890s Klondike, where of 100,000 stampeders, only about 4,000 found workable claims, and fewer than 100 amassed significant stakes amid supply shortages and territorial attrition rates exceeding 70 percent.[103] Romanticized depictions, including 19th-century newspapers hyping "Forty-Niners" as heroic pioneers and later media like Charlie Chaplin's 1925 film The Gold Rush, obscured these realities by foregrounding isolated windfalls—such as the 128-pound nugget found in 1853—while ignoring systemic failures. These narratives fostered a survivorship bias, elevating tales of outliers like John Sutter's fleeting discovery while eliding that placer mining's low barriers to entry invited oversaturation, driving yields below subsistence for most within months. In truth, gold rushes functioned as brutal selection processes, winnowing participants through diminishing marginal returns and environmental rigors rather than rewarding universal pluck; only those pivoting to infrastructure or corporate extraction endured, highlighting causal dynamics of resource exhaustion over lottery-like fortune.[104]Property Rights Conflicts and Legal Precedents

During the California Gold Rush, disputes over mining claims arose frequently due to the absence of formal property titles on public lands, with claim-jumping—reoccupying sites deemed abandoned through insufficient labor—serving as a standard mechanism for reallocating underutilized resources rather than outright theft.[105] Miners' districts, self-organized groups of prospectors, codified rules requiring continuous work to retain claims, typically limiting sizes to 16 feet square per individual for placer deposits, and enforced these through communal arbitration at public meetings, which resolved conflicts efficiently amid sparse state authority.[82] This bottom-up process minimized violence by recognizing both incumbents' investments and newcomers' incentives, fostering a customary law that prioritized productive use over static ownership.[106] State courts gradually integrated these district customs into precedents, as seen in early 1850s rulings affirming possessory rights based on prior discovery and diligent labor, without requiring federal patents until extraction proved viable.[107] The prior appropriation doctrine, emerging from gold rush litigation over water diversions for mining, extended analogous principles to claims by validating first effective possession, as upheld in cases like Irwin v. Phillips (1855), which prioritized users who beneficially applied resources ahead of later arrivals.[108] Weak judicial enforcement in remote areas perpetuated reliance on private adjudication, which proved adaptive and low-cost, prefiguring formal systems like the 1866 federal mining act that codified similar labor-based forfeitures.[87] Conflicts involving foreign miners highlighted tensions in claim eligibility, exemplified by the April 1850 Foreign Miners' Tax imposing $20 monthly on non-citizens, ostensibly for revenue but effectively to curb competition from Chilean, Mexican, and Chinese prospectors amid native-born Americans' perceptions of overcrowding.[109] The levy provoked riots in places like Downieville in 1850 and yielded only sporadic enforcement before repeal in 1851, replaced by lower $3-4 fees that still discriminated but allowed partial integration, influencing later definitions of mineral rights tied to citizenship or residency under evolving common law.[110] These episodes underscored how exclusionary policies clashed with the rush's merit-based ethos, ultimately yielding to pragmatic precedents favoring economic productivity over nativist barriers.Balancing Exploitation Claims Against Innovation Benefits

While claims of exploitation during gold rushes emphasize indigenous displacements and wealth concentration among few participants, quantifiable economic outputs demonstrate broader societal gains that outweighed localized harms. The California Gold Rush generated approximately $400 million in gold between 1848 and 1855, equivalent to roughly $15 billion in modern terms, which accelerated state infrastructure development, including railroads and ports, and supported California's rapid admission to the Union in 1850 as the 31st state.[3] This influx funded agricultural expansion and commerce, transforming a sparsely populated territory into an economic hub without relying on zero-sum redistribution, as newly discovered deposits expanded the global gold supply and stimulated monetary velocity.[111] Similarly, Australian gold rushes from 1851 onward yielded over 2,000 tons of gold by 1900, boosting colonial revenues and population growth from 430,000 in 1851 to over 3.7 million by 1901, which underpinned economic diversification and the push toward federation in 1901 by fostering inter-colonial trade networks and fiscal independence.[22] Critics' plunder narratives overlook how these revenues enabled progressive governance shifts, converting resource-dependent outposts into industrialized societies, with gold taxes alone comprising up to 40% of Victorian government income in the 1850s.[22] Technological advancements born of necessity further illustrate innovation's spillover benefits. The adoption of dynamite, patented in 1867, slashed hardrock mining costs by enabling efficient blasting of ore veins, a technique that miners refined during California and later rushes, yielding productivity gains of up to 40% in excavation while generalizing to civil engineering projects like railroads and canals worldwide.[112] Such developments rewarded entrepreneurial foresight under minimal initial regulation, as free-entry claims incentivized prospecting risks that uncovered viable deposits, rather than stifling output through preemptive controls often justified retrospectively on environmental grounds.[113] Empirical outputs thus affirm that gold rushes created net value through supply expansion and process improvements, countering exploitation framings that undervalue causal links to sustained prosperity.[3]Enduring Legacy

Contributions to Capitalism and Exploration

The California Gold Rush catalyzed the development of financial institutions that underpinned emerging capitalist markets. In San Francisco, the rapid influx of prospectors and capital led to the establishment of multiple mining stock exchanges; by 1864, six such exchanges operated in the city, with nine more near the Comstock Lode and others in Sacramento, facilitating investment in mining claims and joint ventures.[114] The San Francisco Stock and Exchange Board, formed in 1862, marked a pivotal step in organizing speculative trading, drawing eastern capital and professionalizing equity markets for resource extraction.[115] Banking innovations followed suit, including secure express services for gold transport and early forms of deposit insurance; Wells, Fargo & Co., founded on March 18, 1852, pioneered integrated shipping and banking to handle remittances, reducing risks in frontier finance and enabling scalable credit extension.[116] These developments fostered a culture of speculative investment, where individual risk-taking translated into pooled capital for large-scale operations. Gold rushes injected substantial wealth into economies, linking directly to measurable growth. During the 1850s, California's gold production totaled approximately $550 million, equivalent to about 1.8% of U.S. gross domestic product over the decade, spurring ancillary sectors like manufacturing, lumber, and retail to meet surging demand from an influx of over 300,000 migrants.[58] This economic multiplier effect extended beyond extraction, as high gold prices stimulated trade explosions in port cities, with San Francisco's population surging from 1,000 in 1848 to 25,000 by 1850, driving service industries and infrastructure that embedded market-oriented production in the West.[117] Such booms exemplified a risk-reward paradigm, where high-stakes individual ventures—often yielding fortunes or failure—normalized entrepreneurial speculation, reshaping Anglo-American attitudes toward uncertainty and frontier opportunity.[118] The rushes modeled exploration as a high-reward endeavor, influencing subsequent frontier expansions. They accelerated transportation and communication technologies, redirecting steamships and telegraph lines to remote areas, which later informed resource pursuits like oil drilling in the late 19th century.[119] In Australia, the 1850s Victorian rushes pushed settlement into inland Queensland and Western Australia, demonstrating how gold discoveries could compress decades of gradual expansion into rapid colonization driven by prospector mobility.[120] This pattern ingrained a causal logic of incentivized risk: verifiable deposits promised outsized returns, compelling migrants to traverse oceans or mountains, a dynamic echoed in 20th-century tech booms where venture capital mirrored mining stakes. Globally, gold rushes bolstered monetary frameworks that stabilized trade. The California discoveries provided a positive supply shock under the prevailing gold standard, increasing reserves and easing convertibility pressures, which U.S. authorities reinforced by opening a San Francisco mint branch in 1854 to streamline coinage and reduce transport costs.[25] By linking currencies to gold, post-rush adoptions—formalized in Britain by 1821 and spreading internationally—minimized exchange rate volatility, facilitating cross-border commerce as fixed parities encouraged investment flows without hedging premiums.[121] This stability amplified trade volumes, as evidenced by inflationary pressures in supplier regions like China and Mexico during the 1850s, underscoring gold's role in integrating disparate markets under a unified value measure.[14]Lessons for Resource Economics Today

High gold prices, reaching over $3,800 per ounce by October 2025, continue to incentivize exploration and development by junior miners, mirroring the speculative booms of historical rushes where price signals drove rapid resource discovery.[122] However, unlike the individual prospectors dominant in 19th-century rushes, contemporary extraction is led by large corporations with economies of scale, as juniors face funding challenges despite gold's 30% price gain in 2024, often trading at discounts to spot prices.[123] [124] This shift underscores a lesson in resource economics: while high incentives spur entry, barriers to capital and scale favor established entities, potentially concentrating benefits but ensuring sustained output over chaotic individual efforts. Clear property rights regimes, evolved from gold rush precedents like California's 1866 Mining Act establishing private claims on public lands, demonstrably reduce conflicts by minimizing disputes over overlapping tenures that plagued early rushes.[125] [126] Modern applications, such as formalized concessions in stable jurisdictions, correlate with lower incidence of community or inter-firm clashes compared to ambiguous state-controlled systems, as empirical studies of mining districts show that defined titles facilitate investment and orderly development.[127] Technological parallels abound, with AI-driven analytics and drone-based hyperspectral imaging in the 2020s enabling precise prospecting akin to 19th-century hydraulic methods, but with greater efficiency and reduced surface disturbance.[128] [129] Historical rushes empirically validated the superiority of voluntary, private governance in maximizing resource extraction efficiency over state monopolies, as self-organized mining camps enforced rules and allocated claims without central authority, yielding California's transformation from frontier to economic powerhouse within years.[105] [130] Today, this informs caution against overregulation, which can delay projects and inflate costs—evident in U.S. federal permitting backlogs—while innovations like biomining and automation advance sustainability by curbing environmental impacts without prohibitive mandates.[131] [132] Excessive restrictions risk undermining the energy transition's mineral demands, as private incentives historically proved more adept at balancing extraction with adaptive improvements than rigid state controls.[133]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/235082190_Mercury_Bioaccumulation_in_Fish_in_a_Region_Affected_by_Historic_Gold_Mining_The_South_Yuba_River_Deer_Creek_and_Bear_River_Watersheds_California_1999