Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Instrument landing system

View on Wikipedia

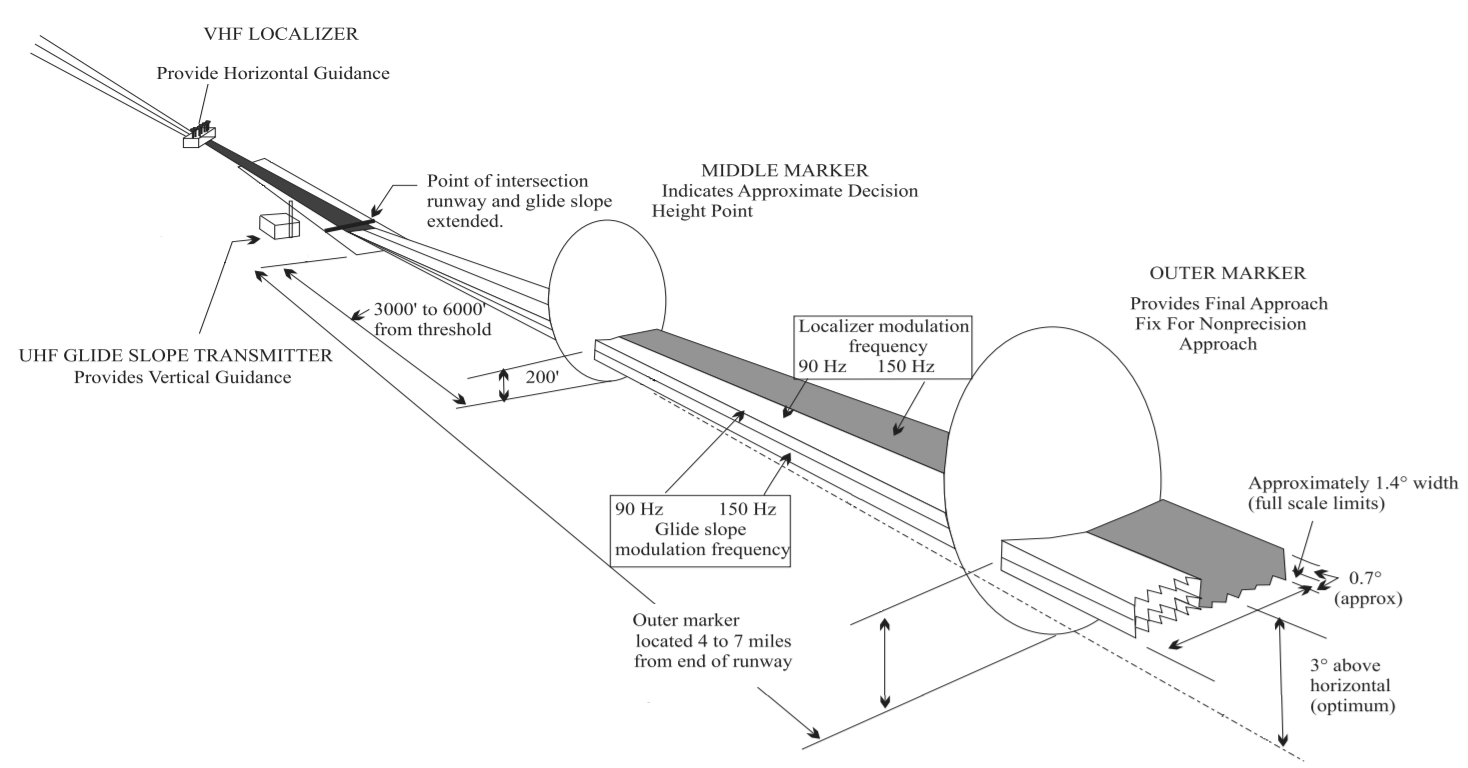

In aviation, the instrument landing system (ILS) is a precision radio navigation system that provides short-range guidance to aircraft to allow them to approach a runway at night or in bad weather. In its original form, it allows an aircraft to approach until it is 200 feet (61 m) over the ground, within a 1⁄2 mile (800 m) of the runway. At that point the runway should be visible to the pilot; if it is not, they perform a missed approach. Bringing the aircraft this close to the runway dramatically increases the range of weather conditions in which a safe landing can be made. Other versions of the system, or "categories", have further reduced the minimum altitudes, runway visual ranges (RVRs), and transmitter and monitoring configurations designed depending on the normal expected weather patterns and airport safety requirements.

ILS uses two directional radio signals, the localizer (108 to 112 MHz frequency), which provides horizontal guidance, and the glideslope (329.15 to 335 MHz frequency) for vertical guidance. The relationship between the aircraft's position and these signals is displayed on an aircraft instrument, often as additional pointers in the attitude indicator. The pilot attempts to maneuver the aircraft to keep the indicators centered while they approach the runway to the decision height. Optional marker beacon(s) provide distance information as the approach proceeds, including the middle marker (MM), placed close to the position of the (CAT 1) decision height. Markers are largely being phased out and replaced by distance measuring equipment (DME).

To aid the transition from instrument landing to visual, lighting on the runway is often extended towards the decision point using a series of high-intensity lights known as the approach lighting system.[1]

History of precision approach landing systems

[edit]A number of radio-based landing systems were developed between the 1920s and 1940s, notably the Lorenz beam, which was a blind-landing radio navigation system developed by C. Lorenz AG for bad weather landing, which saw relatively wide use in Europe and was also installed on a number of airports on other continents worldwide prior to World War II.[2] Later also the patent for adding vertical guidance like in today's ILS was awarded.[3][4]

The US-developed SCS-51 system provided a better accuracy for vertical and horizontal guidance. Many sets were installed at airbases in the United Kingdom during World War II. After the formation of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in 1947, ILS was selected as the first international standard precision approach system[5] and was published in ICAO Annex 10 in 1950.[6] Further development enabled ILS systems to provide up to CAT-III approaches.[5]

The Precision approach radar (PAR) radar-based ground-controlled approach (GCA), provides the pilot with the necessary horizontal and vertical guidance via VHF- or UHF-voice-communication link. The ATC-controller “talks the pilot down” with the PAR derived guidance information displayed on a special Plan position indicator (PPI) via VHF- or UHF-voice-communication. PAR GCA requires no equipment in the aircraft other than the VHF- or UHF-communication equipment, but requires the pilot and controller to be certified for this use.

The second ICAO standard system for precision approach up to CAT-III is the microwave landing system (MLS) which was also planned for implementation by NATO to replace PAR. Due to the foreseen availability of cost-free GPS service for civil use and later the promise of DGPS, to provide additional correctional data via a VHF-Data-Link to improve reliability up to CAT-I level, most states opted to delay, until today, the implementation of MLS. In addition to the cost for the ground-based MLS system, aircraft operators were forced to equip aircraft, in addition to the MLS-receiver, with a C-Band antenna. The retrofit of a C-Band antenna in the aircraft's fuselage is more time consuming and costly than just retrofitting an MLS-receiver. However more than thousand fixed and transportable MLS systems have been deployed, e.g. in Europe, and more than thousand civil and military aircraft were equipped with MLS equipment and antenna and in use for about a decade.

While the promised availability of free access to GPS signals and later additional global navigation satellite systems (GNSSs) for precision approaches reducing the need for the airport infrastructure compared to a single ILS-system (ILS-LLZ, GP and associated Monitors) looked promising. Ensuring safe 24/7 operation identical to ILS with the same continuity of service, under all operational weather conditions, aircraft orientation during all phases of a flight proved to be impossible without an additional augmentation VHF-Data-Link. One reason is the weak satellite based signals, which unlike much stronger ILS- or MLS- signals, very sensitive even to very weak RFI-, intentional Jamming- or Spoofing signals.

The DGPS system was, after further development and modifications, standardized by ICAO as GBAS ground-based augmentation system, in the US known as Local-Area Augmentation System (LAAS). Today GBAS is the third ICAO standard system for precision landing capable of up to CAT-III. Work on standards to support multi-constellation, which means adding support for the now available Galileo, GLONASS and BeiDou GNSS system is ongoing. Like for MLS aircraft require for GBAS a receiver for the GBAS datalink and a horizontally polarized VHF-antenna. While IFR certified civil aircraft are already all equipped with horizontally polarized VHF antennas for ILS- and VOR-reception, some military aircraft only have vertically polarized VHF antennas for VHF voice communication (e.g. USNY). While ICAO also standardized the use of the additional vertical polarization, so far no vertically polarized GBAS installation have been published to be available.

Similar to the MLS until today compared to ILS-installations that are in use worldwide, only a limited number of GBAS systems have been deployed and are still in use currently. While in principle a single omnidirectional augmentation signal was initially thought to suffice to provide service to one or even other airports within radio Line-of-sight propagation (RLOS), providing sufficient coverage within all approach paths provided to be difficult for complex airport layouts with large buildings and Hangars and varying aircraft antenna pattern. Today in Europe mostly serve only a single or parallel runways, e.g. Frankfurt am Main, but not all runways. By 2015, the number of US airports supporting ILS-like LPV approaches exceeded the number of ILS installations,[7] and this may lead to the eventual removal of ILS at most airports.

ILS therefore remains the only available precision approach systems supported by all IFR equipped civil aircraft.

Principle of operation

[edit]

An instrument landing system operates as a ground-based instrument approach system that provides precision lateral and vertical guidance to an aircraft approaching and landing on a runway, using a combination of radio signals and, in many cases, high-intensity lighting arrays to enable a safe landing during instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), such as low ceilings or reduced visibility due to fog, rain, or blowing snow.

Beam systems

[edit]Previous blind landing radio aids typically took the form of beam systems of various types. These normally consisted of a radio transmitter that was connected to a motorized switch to produce a pattern of Morse code dots and dashes. The switch also controlled which of two directional antennae the signal was sent to. The resulting signal sent into the air consists of dots sent to one side of the runway and dashes to the other. The beams were wide enough so they overlapped in the center.[8]

To use the system an aircraft only needed a conventional radio receiver. As they approached the airport they would tune in the signal and listen to it in their headphones. They would hear dots and dashes (Morse code "A" or "N"), if they were to the side of the runway, or if they were properly aligned, the two mixed together to produce a steady tone, the equisignal. The accuracy of this measurement was highly dependent on the skill of the operator, who listened to the signal on earphones in a noisy aircraft, often while communicating with the tower.[8]

Accuracy of the system was normally on the order of 3 degrees in azimuth. While this was useful for bringing the aircraft onto the direction of the runway, it was not accurate enough to safely bring the aircraft to visual range in bad weather; the radio course beams were used only for lateral guidance, and the system was not enough on its own to perform landings in heavy rain or fog. Nevertheless, the final decision to land was made at only 300 metres (980 ft) from the airport.[8]

ILS concept

[edit]The ILS, developed just prior to the start of World War II, used a more complex system of signals and an antenna array to achieve higher accuracy. This requires significantly more complexity in the ground station and transmitters, with the advantage that the signals can be accurately decoded in the aircraft using simple electronics and displayed directly on analog instruments.[8] The instruments can be placed in front of the pilot, eliminating the need for a radio operator to continually monitor the signals and relay the results to the pilot over the intercom.

Key to its operation is a concept known as the amplitude modulation index, a measure of how strongly the amplitude modulation is applied to the carrier frequency. In the earlier beam systems, the signal was turned on and off entirely, corresponding to a modulation index of 100%. The determination of angle within the beam is based on the comparison of the audible strength of the two signals.

In ILS, a more complex system of signals and antennas varies the modulation of two signals across the entire width of the beam pattern. The system relies on the use of sidebands, secondary frequencies that are created when two different signals are mixed. For instance, if one takes a radio frequency signal at 10 MHz and mixes that with an audible tone at 2500 Hz, four signals will be produced, at the original signals' frequencies of 2500 and 10000000 Hz, and sidebands 9997500 and 10002500 Hz. The original 2500 Hz signal's frequency is too low to travel far from an antenna, but the other three signals are all radio frequency and can be effectively transmitted.[9]

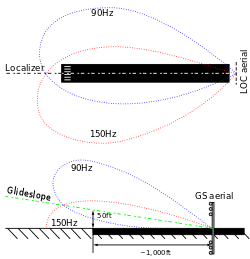

ILS starts by mixing two modulating signals to the carrier, one at 90 Hz and another at 150. This creates a signal with five radio frequencies in total, the carrier and four sidebands. This combined signal, known as the CSB for "carrier and sidebands", is sent out evenly from an antenna array. The CSB is also sent into a circuit that suppresses the original carrier, leaving only the four sideband signals. This signal, known as SBO for "sidebands only", is also sent to the antenna array.[9]

For lateral guidance, known as the localizer, the antenna is normally placed centrally at the far end of the runway and consists of multiple antennas in an array normally about the width of the runway. Each individual antenna has a particular phase shift and power level applied only to the SBO signal such that the resulting signal is retarded 90 degrees on the left side of the runway and advanced 90 degrees on the right. Additionally, the 150 Hz signal is inverted on one side of the pattern, another 180 degree shift. Due to the way the signals mix in space the SBO signals destructively interfere with and almost eliminate each other along the centerline, leaving the CSB signal predominating. At any other location, on either side of the centerline, the SBO and CSB signals combine in different ways so that one modulating signal predominates.[9]

A receiver in front of the array will receive both of these signals mixed together. Using simple electronic filters, the original carrier and two sidebands can be separated and demodulated to extract the original amplitude-modulated 90 and 150 Hz signals. These are then averaged to produce two direct current (DC) signals. Each of these signals represents not the strength of the original signal, but the strength of the modulation relative to the carrier, which varies across the beam pattern. This has the great advantage that the measurement of angle is independent of range.[9]

The two DC signals are then sent to a conventional voltmeter, with the 90 Hz output pulling the needle right and the other left. Along the centreline the two modulating tones of the sidebands will be cancelled out and both voltages will be zero, leaving the needle centered in the display. If the aircraft is far to the left, the 90 Hz signal will produce a strong DC voltage (predominates), and the 150 Hz signal is minimised, pulling the needle all the way to the right. This means the voltmeter directly displays both the direction and magnitude of the turn needed to bring the aircraft back to the runway centreline.[9] As the measurement compares different parts of a single signal entirely in electronics, it provides angular resolution of less than a degree, and allows the construction of a precision approach.[9]

Although the encoding scheme is complex, and requires a considerable amount of ground equipment, the resulting signal is both far more accurate than the older beam-based systems and is far more resistant to common forms of interference. For instance, static in the signal will affect both sub-signals equally, so it will have no effect on the result. Similarly, changes in overall signal strength as the aircraft approaches the runway, or changes due to fading, will have little effect on the resulting measurement because they would normally affect both channels equally. The system is subject to multipath distortion effects due to the use of multiple frequencies, but because those effects are dependent on the terrain, they are generally fixed in location and can be accounted for through adjustments in the antenna or phase shifters.[9]

Additionally, because it is the encoding of the signal within the beam that contains the angle information, not the strength of the beam, the signal does not have to be tightly focussed in space. In the older beam systems, the accuracy of the equisignal area was a function of the pattern of the two directional signals, which demanded that they be relatively narrow. The ILS pattern can be much wider. ILS installations are normally required to be usable within 10 degrees on either side of the runway centerline at 25 nautical miles (46 km; 29 mi), and 35 degrees on either side at 17 nautical miles (31 km; 20 mi). This allows for a wide variety of approach paths.[10]

The glideslope works in the same general fashion as the localizer and uses the same encoding, but is normally transmitted to produce a centerline at an angle of 3 degrees above horizontal[a] from an antenna beside the runway instead of the end. The only difference between the signals is that the localizer is transmitted using lower carrier frequencies, using 40 selected channels between 108.10 MHz and 111.95 MHz, whereas the glideslope has a corresponding set of 40 channels between 328.6 and 335.4 MHz. The higher frequencies generally result in the glideslope radiating antennas being smaller. The channel pairs are not linear; localizer channel 1 is at 108.10 and paired with glideslope at 334.70, whereas channel two is 108.15 and 334.55. There are gaps and jumps through both bands.[10][11]

Many illustrations of the ILS concept show the system operating more similarly to beam systems with the 90 Hz signal on one side and the 150 on the other. These illustrations are inaccurate; both signals are radiated across the entire beam pattern, it is their relative difference in the depth of modulation (DDM) that changes dependent upon the position of the approaching aircraft.

Using ILS

[edit]An instrument approach procedure chart (or 'approach plate') is published for each ILS approach to provide the information needed to fly an ILS approach during instrument flight rules (IFR) operations. A chart includes the radio frequencies used by the ILS components or navaids and the prescribed minimum visibility requirements.

An aircraft approaching a runway is guided by the ILS receivers in the aircraft by performing modulation depth comparisons. Many aircraft can route signals into the autopilot to fly the approach automatically. An ILS consists of two independent sub-systems. The localizer provides lateral guidance; the glide slope provides vertical guidance.

Localizer

[edit]

A localizer (LOC, or LLZ until ICAO standardisation[12]) is an antenna array normally located beyond the departure end of the runway and generally consists of several pairs of directional antennas.

The localizer will allow the aircraft to turn and match the aircraft with the runway. After that, the pilots will activate approach phase (APP).

Glide slope (G/S)

[edit]

The pilot controls the aircraft so that the glide slope indicator remains centered on the display to ensure the aircraft is following the glide path of approximately 3° above horizontal (ground level) to remain above obstructions and reach the runway at the proper touchdown point (i.e. it provides vertical guidance).

Limitations

[edit]Due to the complexity of ILS localizer and glide slope systems, there are some limitations. Localizer systems are sensitive to obstructions in the signal broadcast area, such as large buildings or hangars. Glide slope systems are also limited by the terrain in front of the glide slope antennas. If terrain is sloping or uneven, reflections can create an uneven glidepath, causing unwanted needle deflections. Additionally, since the ILS signals are pointed in one direction by the positioning of the arrays, glide slope supports only straight-line approaches with a constant angle of descent. Installation of an ILS can be costly because of siting criteria and the complexity of the antenna system.

ILS critical areas and ILS sensitive areas are established to avoid hazardous reflections that would affect the radiated signal. The location of these critical areas can prevent aircraft from using certain taxiways[13] leading to delays in takeoffs, increased hold times, and increased separation between aircraft.

Variant

[edit]- Instrument guidance system (IGS) (localizer type directional aid (LDA) in the United States) – a modified ILS to accommodate a non-straight approach; the most famous example was for the approach to runway 13 at Kai Tak Airport, Hong Kong.[14][15]

- Instrument carrier landing system (ICLS) – a modified ILS for (aircraft) carrier landing.

Identification

[edit]In addition to the previously mentioned navigational signals, the localizer provides for ILS facility identification by periodically transmitting a 1,020 Hz Morse code identification signal, that always starts with Morse Code letter "I", for ILS, two dots. For example, the ILS for runway 4R at John F. Kennedy International Airport transmits IJFK to identify itself, while runway 4L is known as IHIQ. This lets users know the facility is operating normally and that they are tuned to the correct ILS. The glide slope station transmits no identification signal, so ILS equipment relies on the localizer for identification.

Monitoring

[edit]It is essential that any failure of the ILS to provide safe guidance be detected immediately by the pilot. To achieve this, monitors continually assess the vital characteristics of the transmissions. If any significant deviation beyond strict limits is detected, either the ILS is automatically switched off or the navigation and identification components are removed from the carrier.[16] Either of these actions will activate an indication ('failure flag') on the instruments of an aircraft using the ILS.

Localizer back course

[edit]Modern localizer antennas are highly directional. However, usage of older, less directional antennas allows a runway to have a non-precision approach called a localizer back course. This lets aircraft land using the signal transmitted from the back of the localizer array. Highly directional antennas do not provide a sufficient signal to support a back course. In the United States, back course approaches are typically associated with Category I systems at smaller airports that do not have an ILS on both ends of the primary runway. Pilots flying a back course should disregard any glide slope indication.

Marker beacons

[edit]On some legacy installations, marker beacons operating at a carrier frequency of 75 MHz are provided. When the transmission from a marker beacon is received it activates an indicator on the pilot's instrument panel and the identity code and tone of the beacon is audible to the pilot. The distance from the runway at which this indication should be received is published in the documentation for that approach, together with the height at which the aircraft should be if correctly established on the ILS. This provides a check on the correct function of the glide slope. Instead of marker beacons, modern ILS installations use DME. Co-located with the ILS glidepath transmitter near the touchdown point, the DME provides a display of aircraft distance to the runway.

DME substitution

[edit]Distance measuring equipment (DME) provides pilots with a slant range measurement of distance to the runway. DMEs are augmenting or replacing markers in many installations. The DME provides more accurate and continuous monitoring of correct progress on the ILS glide slope to the pilot, and does not require an installation outside the airport boundary. When used in conjunction with a dual runway approach ILS, the DME is often sited midway between the reciprocal runway thresholds with the internal delay modified so that one unit can provide distance information to either runway threshold. For approaches where a DME is specified in lieu of marker beacons, DME required is noted on the instrument approach procedure and the aircraft must have at least one operating DME unit, or an IFR-approved system using a GNSS (an RNAV system meeting TSO-C129/ -C145/-C146),[17] to begin the approach.

Compass locator

[edit]Compass locators are low-powered (less than 25 W) non-directional beacons and are received and indicated by the automatic direction finder receiver. It ranges over 15 miles and operate between 190 and 535 kHz. When used in conjunction with an ILS front course, the compass locator facilities are collocated with the outer and/or middle marker facilities and can be used to substitute an outer marker, in which case it will transmit at 400 W. The coding identification of the outer locator consists of the first two letters of the three-letter identifier of the associated localizer.[18][19]

Approach lighting

[edit]

Some installations include medium- or high-intensity approach light systems (abbreviated ALS). Most often, these are at larger airports but many small general aviation airports in the U.S. have approach lights to support their ILS installations and obtain low-visibility minimums. The ALS assists the pilot in transitioning from instrument to visual flight, and to align the aircraft visually with the runway centerline. Pilot observation of the approach lighting system at the Decision Altitude allows the pilot to continue descending towards the runway, even if the runway or runway lights cannot be seen, since the ALS counts as runway end environment. In the U.S., an ILS without approach lights may have CAT I ILS visibility minimums as low as 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) (runway visual range of 4,000 feet (1,200 m)) if the required obstacle clearance surfaces are clear of obstructions.

Visibility minimums of 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) (runway visual range of 2,400 feet (730 m)) are possible with a CAT I ILS approach supported by a 1,400-to-3,000-foot-long (430 to 910 m) ALS, and 3⁄8 mile (600 m) visibility 1,800-foot (550 m) visual range is possible if the runway has high-intensity edge lights, touchdown zone and centerline lights, and an ALS that is at least 2,400 feet (730 m) long (see Table 3-3-1 "Minimum visibility values" in FAA Order 8260.3C).[20] In effect, ALS extends the runway environment out towards the landing aircraft and allows low-visibility operations. CAT II and III ILS approaches generally require complex high-intensity approach light systems, while medium-intensity systems are usually paired with CAT I ILS approaches. At some non-towered airports, the pilot controls the lighting system; for example, the pilot can key the microphone seven times to turn on the lights on the high intensity, five times to medium intensity or three times for low intensity.[citation needed]

Decision altitude and height

[edit]Once established on an approach, the pilot follows the ILS approach path indicated by the localizer and descends along the glide path to the decision height. This is the height at which the pilot must have adequate visual reference to the landing environment (e.g. approach or runway lighting) to decide whether to continue the descent to a landing; otherwise, the pilot must execute a missed approach procedure, then try the same approach again, try a different approach, or divert to another airport. Usually, the decision on whether or not the pilot continues with the approach relies on whether the runway is visible or not, or if the runway is clear or not.

ILS categories

[edit]| Category | Decision height | Runway visual range (RVR) |

|---|---|---|

| I[22] | > 200 ft (60 m)[b] | > 550 m (1,800 ft)[c] or visibility > 800 m (2,600 ft)[d] |

| II | 100–200 ft (30–60 m) | > 1,000 ft (300 m)[e] or > 1,200 ft (350 m) |

| III A | < 100 ft (30 m) | > 700 ft (200 m) |

| III B | < 50 ft (15 m) | 150–700 ft (50–200 m) |

| III C[f] | No limit | None |

- ^ The slope is selected by the airport, London City Airport has an unusually high glideslope angle of 5.5 degrees.

- ^ 150 ft (46 m) allowed by FAA with RVR > 1,400 ft (430 m), CAT II aircraft and crew, CAT II/III HUD and CAT II/III missed approach.[23]

- ^ Properly equipped runways (HIAL, TDZL, CL) and/or use of FD or AP or HUD to DA.[24] 2,600 ft (790 m) RVR for single crew[citation needed]

- ^ No touchdown zone, no centerline lighting

- ^ Airports approved for scheduled air carrier operations with less than 1,200 feet of RVR are required to have additional lighting systems.[24]

- ^ Not used as an aircraft would have to be towed from the runway.[22]

| Category | Decision height | Runway visual range (RVR) |

|---|---|---|

| Type A | ≥ 250 ft (75 m) | Not specified |

| Type B – CAT I | 200–250 ft (60–75 m) | ≥ 1,800 ft (550 m) or visibility ≥ 2,400 ft (800 m) |

| Type B – CAT II | 100–200 ft (30–60 m) | ≥ 1,000 ft (300 m) |

| Type B – CAT III | < 100 ft (30 m) |

Smaller aircraft generally are equipped to fly only a CAT I ILS. On larger aircraft, these approaches typically are controlled by the flight control system with the flight crew providing supervision. CAT I relies only on altimeter indications for decision height, whereas CAT II and CAT III approaches use radio altimeter (RA) to determine decision height.[26]

An ILS must shut down upon internal detection of a fault condition. Higher categories require shorter response times; therefore, ILS equipment is required to shut down more quickly. For example, a CAT I localizer must shut down within 10 seconds of detecting a fault, but a CAT III localizer must shut down in less than 2 seconds.[16]

Special CAT II and CAT III operations

[edit]

In contrast to other operations, CAT III weather minima do not provide sufficient visual references to allow a manual landing to be made. CAT IIIb minima depend on roll-out control and redundancy of the autopilot,[citation needed] because they give only enough time for the pilot to decide whether the aircraft will land in the touchdown zone (basically CAT IIIa) and to ensure safety during rollout (basically CAT IIIb). Therefore, an automatic landing system is mandatory to perform Category III operations. Its reliability must be sufficient to control the aircraft to touchdown in CAT IIIa operations and through rollout to a safe taxi speed in CAT IIIb (and CAT IIIc when authorized).[27] However, special approval has been granted to some operators for hand-flown CAT III approaches using a head-up display (HUD) guidance that provides the pilot with an image viewed through the windshield with eyes focused at infinity, of necessary electronic guidance to land the airplane with no true outside visual references.

In the United States, airports with CAT III approaches have listings for CAT IIIa and IIIb or just CAT III on the instrument approach plate (U.S. Terminal Procedures). CAT IIIb RVR minimums are limited by the runway/taxiway lighting and support facilities, and are consistent with the airport surface movement guidance control system (SMGCS) plan. Operations below 600 ft RVR require taxiway centerline lights and taxiway red stop bar lights. If the CAT IIIb RVR minimums on a runway end are 600 feet (180 m), which is a common figure in the U.S., ILS approaches to that runway end with RVR below 600 feet (180 m) qualify as CAT IIIc and require special taxi procedures, lighting, and approval conditions to permit the landings. FAA Order 8400.13D limits CAT III to 300 ft RVR or better. Order 8400.13D (2009) allows special authorization CAT II approaches to runways without ALSF-2 approach lights and/or touchdown zone/centerline lights, which has expanded the number of potential CAT II runways.

In each case, a suitably equipped aircraft and appropriately qualified crew are required. For example, CAT IIIb requires a fail-operational system, along with a crew who are qualified and current, while CAT I does not. A HUD that allows the pilot to perform aircraft maneuvers rather than an automatic system is considered as fail-operational. A HUD allows the flight crew to fly the aircraft using the guidance cues from the ILS sensors such that if a safe landing is in doubt, the crew can respond in an appropriate and timely manner. HUD is becoming increasingly popular with "feeder" airlines and most manufacturers of regional jets are now offering HUDs as either standard or optional equipment.[citation needed] A HUD can provide capability to take off in low visibility.

Some commercial aircraft are equipped with automatic landing systems that allow the aircraft to land without transitioning from instruments to visual conditions for a normal landing. Such autoland operations require specialized equipment, procedures and training, and involve the aircraft, airport, and the crew. Autoland is the only way some major airports such as Charles de Gaulle Airport remain operational every day of the year. Some modern aircraft are equipped with enhanced flight vision systems based on infrared sensors, that provide a day-like visual environment and allow operations in conditions and at airports that would otherwise not be suitable for a landing. Commercial aircraft also frequently use such equipment for takeoffs when takeoff minima are not met.[28]

For both automatic and HUD landing systems, the equipment requires special approval for its design and also for each individual installation. The design takes into consideration additional safety requirements for operating an aircraft close to the ground and the ability of the flight crew to react to a system anomaly. The equipment also has additional maintenance requirements to ensure that it is capable of supporting reduced visibility operations.

Nearly all of this pilot training and qualification work is done in simulators with various degrees of fidelity.

Use

[edit]At a controlled airport, air traffic control will direct aircraft to the localizer course via assigned headings, making sure aircraft do not get too close to each other (maintain separation), but also avoiding delay as much as possible. Several aircraft can be on the ILS at the same time, several miles apart. An aircraft that has turned onto the inbound heading and is within two and a half degrees of the localizer course (half scale deflection or less shown by the course deviation indicator) is said to be established on the approach. Typically, an aircraft is established by at least 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) prior to the final approach fix (glideslope intercept at the specified altitude).

Aircraft deviation from the optimal path is indicated to the flight crew by means of a display dial (a carryover from when an analog meter movement indicated deviation from the course line via voltages sent from the ILS receiver).

The output from the ILS receiver goes to the display system (head-down display and head-up display if installed) and may go to a Flight Control Computer. An aircraft landing procedure can be either coupled where the autopilot or Flight Control Computer directly flies the aircraft and the flight crew monitor the operation, or uncoupled where the flight crew flies the aircraft manually to keep the localizer and glideslope indicators centered.

History

[edit]

Tests of the ILS began in 1929 in the United States, with Jimmy Doolittle becoming the first pilot to take off, fly and land an airplane using instruments alone, without a view outside the cockpit.[29][30] Doolittle flew a Consolidated NY2 equipped with a Sperry artificial horizon and gyroscope, a Paul Kollsman altimeter, and a tuned reed indicator to visualize his relationship to a National Bureau of Standards localizer.[31][32]

In 1928, the NSB's Harry Diamond proposed modifying low-frequency radio range as a localizer directional beam, supplemented with two high frequency beacons aligned with the approach path, while Francis Dunmore proposed a landing beam angled up from the ground as a safe glide slope. The combination of localizer, marker beacons, and glide slope provided a three dimensional path to the airport. In 1934, United Airlines, working with Bendix Aviation, modified this NSB system with a UHF localizer, producing an approach aid. Though not appropriate for blind landings, it became a system for instrument low approaches to within an altitude of two hundred feet, from which a pilot could then land visually. Duplicated in Japan, the Soviet Union, while in 1932, Ernst Kramar developed the idea in a joint project between Lorenz, Telefunken and Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt. This version was quickly adopted in Europe.[31]: 59–78

Between 1931 and 1933, Albert Francis Hegenberger developed the U.S. Army system called A-1. WWI radio direction finders, radio compasses, were deployed on aircraft as an automatic direction finder by Geoffrey Kreusi. The A-1 system used two omnidirectional radio transmitters called compass locators, one next to the airport, and another 1.5 miles away. After WWII, a compass locator was added to the NSB marker beacon as an approach aid. In 1933, the U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence cloned the NSB system into their YB system. Though unsuitable for carrier landings, the navy used it for seaplanes. In 1938, a commercial version of the YB system manufactured by Air-Track Corporation was used in the first passenger flight blind landing.[31]

A basic system, fully operative, was introduced in 1932 at Berlin-Tempelhof Central Airport (Germany) named LFF or "Lorenz beam" after its inventor, the C. Lorenz AG company. The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) of the United States authorized installation of the system in 1941 at six locations. The first landing of a scheduled U.S. passenger airliner using ILS was on January 26, 1938, when a Pennsylvania Central Airlines Boeing 247D flew from Washington, D.C., to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and landed in a snowstorm using only the Instrument Landing System.[33]

Yet, the NSB system, and derivatives, had several limitations, including not having a straight glide path. The current curved glidepath resulted in flying at an altitude of 50 feet, a half mile before entering the airport boundary. A straight glide path was needed to simplify the approach and ensure obstacle clearance. The army wanted a ten mile straight glide path. The current system also used the earth's surface as a reflector, which destabilized and distorted the glidepath with changing surface conditions. In 1938, the Bureau of Air Commerce contracted the ITT to improve the NSB system. In 1939, the improved system was demonstrated in Indianapolis, though it still had a 2-3 mile curved glide slope. In 1940, President Roosevelt approved a National Academy of Sciences recommendation allowing the Civil Aeronautics Authority to install ten ITT Indianapolis systems , while the army pursued a microwave system development project with MIT. With the advent of WWII in 1941, the army began deploying the CAA localizer and marker beacon systems throughout the U.S., while the AAF and CAA adopted standard approach procedures for each airport.[31]: 83–89, 104, 109

In 1942, the Army Air Force (AAF) took over the CAA Indianapolis facility and began developing an army version with the help of ITT's International Telephone and Radio Manufacturing Company. The 110 MHz localizer and 93.7 MHz glide path were both replaced with 330 MHz electronics, which reduced environmental influences, the glidepath was made straight, and the system made portable with standard vacuum tube sets. In 1942, the AAF initiated testing of this SCS-51 system. In 1943, the system became the standard for both the army and navy, and was deployed along the North Atlantic air ferry route. In 1944, the SCS-51 was adopted by the Eighth Air Force, the Ninth Air Force, and the RAF, in the European theater.[31]: 104–113 .

In 1946, the Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization adopted the VOR and DME airways model. Nations took over, and expanded, the facilities established during the war by the Air Transport Command. The SCS-51 was also adopted as the international standard, since the system also was available to use immediately, easy and inexpensive to manufacture, without any proprietary or military secrets.[31]: 119–122

The first fully automatic landing by a commercial airliner using ILS occurred in March 1964 at Bedford Airport in the UK.[citation needed]

Market

[edit]The instrument landing systems market revenue was US$1,215 million in 2019, and is expected to reach US$1,667 million in 2025, with a CAGR of 5.41% during 2020–2025 even with the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.[34]

Suppliers

[edit]The top 10 manufacturers of instrument landing systems are:

Alternatives

[edit]- The microwave landing system (MLS) allowed for curved approaches. It was introduced in the 1970s[35] to replace ILS but fell out of favor because of the introduction of satellite based systems. In the 1980s, there was a major US and European effort to establish MLS. But a combination of airline reluctance to invest and the rise of global navigation satellite system (GNSS) resulted in its not being adopted in civil aviation. At the time ILS and MLS were the only standardized systems in Civil Aviation that meet requirements for Category III automated landings.[36] The first Category III MLS for civil aviation was commissioned at Heathrow airport in March 2009 and removed from service in 2017.[37]

- Transponder landing system (TLS) can be used where a conventional ILS cannot work or is not cost-effective.

- Localizer performance with vertical guidance (LPV) is based on the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS), LPV has similar minima to ILS for appropriately equipped aircraft. As of November 2008[update], the FAA has published more LPV approaches than Category I ILS procedures.

- Ground-based augmentation system (GBAS) (local-area augmentation system in the United States) is a safety-critical system that augments the GNSS Standard Positioning Service (SPS) and provides enhanced levels of service. It supports all phases of approach, landing, departure, and surface operations within the VHF coverage volume. GBAS is expected to play a key role in modernization and in all-weather operations capability at CATI/II and III airports, terminal area navigation, missed approach guidance and surface operations. GBAS provides the capability to service the entire airport with a single frequency (VHF transmission) whereas ILS requires a separate frequency for each runway end. GBAS CAT-I is seen as a necessary step towards the more stringent operations of CAT-II/III precision approach and landing. The technical risk of implementing GBAS delayed widespread acceptance of the technology. The FAA, along with industry, have fielded Provably Safe Prototype GBAS stations that mitigate the impact of satellite signal deformation, ionosphere differential error, ephemeris error, and multipath.

Future

[edit]The advent of the Global Positioning System (GPS) provides an alternative source of approach guidance for aircraft. In the US, the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) has been available in many regions to provide precision guidance to Category I standards since 2007. The equivalent European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS) was certified for use in safety of life applications in March 2011.[38] As such, the number of Cat I ILS installations may be reduced, however there are no plans in the United States to phase out any Cat II or Cat III systems.[39]

Local Area Augmentation System (LAAS) is under development to provide for Category III minimums or lower. The FAA Ground-Based Augmentation System (GBAS) office is currently working with the industry in anticipation of the certification of the first GBAS ground stations in Memphis, TN; Sydney, Australia; Bremen, Germany; Spain; and Newark, NJ. All four countries have installed GBAS ground stations and are involved in technical and operational evaluation activities.

The Honeywell and FAA team obtained System Design Approval of the world's first non-federal U.S. approval for LAAS Category I at Newark Liberty International Airport, operations in September 2009 and Operational Approval on September 28, 2012.[40]

In Norway, a D-GPS based landing system, called SCAT-I, is in operation on some short runway airports.

See also

[edit]- Acronyms and abbreviations in avionics

- Airspeed

- AN/CRN-2 SCS-51 glide slope

- AN/MRN-1 SCS-51 localizer

- AN/MRN-3 SCS-51 marker beacon

- Autoland

- Blind approach beacon system (BABS)

- CFIT

- Distance measuring equipment (DME)

- EGPWS

- Flight director, FD

- Fog

- George Vernon Holloman – the pilot who made first automated landing

- Global Positioning System (GPS)

- HUD

- Instrument flight rules (IFR)

- Local Area Augmentation System (LAAS)

- Localizer performance with vertical guidance (LPV)

- Lorenz beam

- Microwave landing system (MLS)

- Non-directional beacon (NDB)

- Precision approach radar (PAR)

- Space modulation

- Transponder landing system (TLS)

- Visual flight rules (VFR)

- VHF omnidirectional range (VOR)

- Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Wragg, David W. (1973). A Dictionary of Aviation (1st ed.). Osprey. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-85045-163-4.

- ^ "Ultra-Short Wave Radio Landing Beam, The C. Lorenz-A.G. Radio Beacon Guide Beam System, R. ELSNER AND E. KRAMAR," (PDF). Electrical Communication, January.1937, No.3, Vol.15, p. 195 ff (PDF).

- ^ Reichspatentamt Patentschrift Nr. 720 890, Anordnung zur Erzeugung einer gradlinigen Gleitwegführung für Flugzeuglandezwecke, Dr.-Ing. Ernst Kramar, Dr.-Ing. Werner Gerbes, 1937.November.5 (PDF).

- ^ Ultra-Short Wave Radio Landing Beam, The C. Lorenz-A.G. Radio Beacon Guide Beam System, R. Elsner and E. Kramar, Electrical Communication, January.1937, No.3, Vol.15, p. 195 ff (PDF).

- ^ a b The Development of the Civil Aeronautics Authority Instrument Landing System at Indianapolis, W. E. Jackson, A. Alford, P. F. Byrne, H. B. Fischer, Electrical Communication, April.1940, Vol.18, Number 4 (PDF).

- ^ ICAO, International Standards and Recommended Practices, Aeronautical Telecommunications, Annex 10, ed. 1, Mai 1950.

- ^ "Satellite Navigation – GPS/WAAS Approaches".

- ^ a b c d "History of Radio Flight Navigation Systems" (PDF). Radar World. pp. 2–4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Balmus, Elena (16 April 2019). "An Introduction into the Signals of ILS, DME and VOR". SkyRadar.

- ^ a b "Instrument Landing System" (PDF). Nordian.

- ^ "Localizer and Glide slope Frequency Pairing". FCC.

- ^ "ICAO DOC8400 Amendment 28". icao.int. Archived from the original on 2014-02-23.

- ^ FAA, ILS Glide Slope Critical Area Advisory (archived): pg 4, ILS Course Distortion

- ^ "Approach chart of Kai Tak Airport runway 13". flyingtigersgroup.org. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03.

- ^ Kai Tak Airport#Runway 13 approach

- ^ a b Department of Transportation and Department of Defense (March 25, 2002). "2001 Federal Radionavigation Systems" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2005.

- ^ "AC90-108" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ "Chapter 9. Navigation Systems". Instrument Flying Handbook (PDF) (FAA-H-8083-15B ed.). Federal Aviation Administration Flight Standards Service. 2012. p. 38.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "ENR 4.1 Navigation Aids – En Route". Aeronautical Information Publication. Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ FAA Order 8260.3C, United States Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS) Archived 2017-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, effective 2016-03-14, accessed 2017-12-04

- ^ "Getting to grips with CAT II / CAT III operations" (PDF). Airbus. Oct 2001.

- ^ a b "Navigation instrumentation – ILS" (PDF). IVAO training. 31 May 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Order 8400.13D". FAA. May 15, 2018. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ^ a b "FAA Order 8400.13E - Procedures for the Evaluation and Approval of Facilities for Special Authorization Category I Operations and All Category II and III Operations" (PDF). faa.gov. Retrieved 15 December 2025.

- ^ "Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/208 of 14 December 2021 amending Regulation (EU) No 139/2014 as regards the requirements for all-weather operations (Text with EEA relevance)". EUR-Lex / Official Journal of the European Union. 2022-02-17. Retrieved 2025-09-19.

- ^ ICAO Annex 10 Aeronautical Telecommunications, Volume 1 (Radio Navigation Aids) 2.1.1 (incomplete citation)

- ^ "Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance Material (GM) to Part-SPA" (PDF). Annex to ED Decision 2012-019-R. EASA. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ For example, Southwest Airlines flies HUD equipped Boeing 737 aircraft to fog-prone airports such as Sacramento International (KSMF), allowing flights to take off when they would otherwise be unable to do so.

- ^ Preston, Edmund (ed.). "FAA Historical Chronology: Civil Aviation and the Federal Government, 1926–1996" (PDF). Repository and Open Science Access Portal; National Transportation Library; United States Department of Transportation. United States Federal Aviation Administration. p. 9. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

Sep 24, 1929: At Mitchel Field, N.Y., Army Lt. James H. Doolittle became the first pilot to use only instrument guidance to take off, fly a set course, and land. Doolittle received directional guidance from a radio range course aligned with the airport runway, while radio marker beacons indicated his distance from the runway. [...] He flew in a hooded cockpit, but was accompanied by a check pilot who could have intervened in an emergency.

- ^ "Planes Are Landing By Radio When Fog Hides The Field", February 1931, Popular Mechanics bottom-right of page

- ^ a b c d e f Conway, Erik (2006). Blind Landings: Low-Visibility Operations in American Aviation, 1918-1958. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 52–62. ISBN 9780801884498.

- ^ Dunmore, F.W. (1928). "Design of Tuned Reed Course Indicators for Aircraft Radiobeacon" (PDF). Bureau of Standards Journal of Research. pp. 751–769. Retrieved 16 December 2025.

- ^ Mola, Roger. "History of Aircraft Landing Aids". centennialofflight.net. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Instrument Landing Systems(Ils) Market Share, Size Global Regional Analysis, Key Findings, Growth Factors, Industry Demand, Key Players Profiles, Future Prospects and Forecasts to 2025 (Marketwatch) https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/instrument-landing-systemsils-market-share-size-global-regional-analysis-key-findings-growth-factors-industry-demand-key-players-profiles-future-prospects-and-forecasts-to-2025-2021-08-26 Archived 2021-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Microwave Landing System For Jets Is Demonstrated". New York Times. May 20, 1976.

- ^ "Annex 10 – Aeronautical Telecommunications, Volume I (Radio Navigation Aids) Amendment 81" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-15.

- ^ NATS (March 26, 2009). "Worlds first low-visibility microwave landing system comes into operation at Heathrow". atc-network.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07.

- ^ "EGNOS navigation system begins serving Europe's aircraft". Archived from the original on 2011-03-06. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

References

[edit]- ICAO Annex 10 Volume 1, Radio Navigation Aids, Fifth Edition — July 1996

- Aeronautical Information Manual, FAA – February 11, 2010

- Digital Terminal Procedures, FAA – May 2010

External links

[edit]- History of Aircraft Landing Aids – U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission

- "Happy Landings In Fog", June 1933, Popular Mechanics article on the early system setup in the USA.

- ILS Basics

- ILS Tutorial Animations

- Website dedicated to the description of ILS

- ILS Tutorial Animation Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine - Illustrates and describes how ILS navigation signals are displayed on board of an aircraft in various positions, which may occur during a safe approach for landing.

- Categories of the ILS Archived 2014-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Jackson, Hagan L. (January 1947). "New Instrument System Proposed for Flight and Landing Safety". Aviation. Vol. 46, no. 1. pp. 86–88. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Instrument Landing System (ILS): Enhancing Aircraft Precision and Safety