Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chawan

View on Wikipedia

| Chawan | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 茶碗 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "tea bowl" | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Alternate Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 茶盞 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 茶盏 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "tea cup" | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | trà oản | ||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 茶碗 | ||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 찻사발, 다완 | ||||||||||||||

| Hanja | n/a, 茶碗 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "tea bowl" | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 茶碗 | ||||||||||||||

| Kana | ちゃわん | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

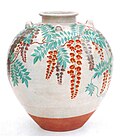

A chawan (茶碗; literally "tea bowl") is a bowl used for preparing and drinking tea. Many types of chawan are used in East Asian tea ceremonies.

History

[edit]

The chawan originated in China. The earliest chawan in Japan were imported from China between the 13th and the 16th centuries.[1]

The Jian chawan, a Chinese tea bowl known as Tenmoku chawan in Japan, was the preferred tea bowl for the Japanese tea ceremony until the 16th century.[2] In Japan, tea was also mainly drunk from this Chinese variety of tea bowls until about the 15th century.[3] The Japanese term tenmoku is derived from the name of the Tianmu Mountain, where Japanese priests acquired these tea bowls from Chinese temples to bring back to Japan, according to tradition.[4]

An 11th-century resident of Fujian wrote about the Jian tea wares:

Tea is of light colour and looks best in black cups. The cups made at Jianyang are bluish-black in colour, marked like the fur of a hare. Being of rather thick fabric, they retain the heat, so that when once warmed through, they cool very slowly, and they are additionally valued on this account. None of the cups produced at other places can rival these. Blue and white cups are not used by those who give tea-tasting parties.[5]

By the end of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), as the custom of tea drinking spread throughout Japan and the Tenmoku chawan became desired by all ranks of society, the Japanese began to make their own copies in Seto (in present-day Aichi Prefecture).[6] Although the Tenmoku chawan was derived from the original Chinese that came in various colors, shapes, and designs, the Japanese particularly liked the bowls with a tapered shape, so most Seto-made Tenmoku chawan had this shape.[6]

With the rise of the wabi tea ceremony in the late Muromachi period (1336–1573), the Ido chawan, which originated from a Met-Saabal or a large bowl used for rice in Korea, also became highly prized in Japan.[7] These Korean-influenced bowls were favored by the tea master Sen no Rikyū because of their rough simplicity.[8]

Over time and with the development of the Japanese tea ceremony as a distinct form, local Japanese pottery and porcelain became more highly priced and developed. Around the Edo period, the chawan was often made in Japan. The most esteemed pieces for a tea ceremony chawan are raku ware, Hagi ware, and Karatsu ware. A saying in the tea ceremony schools for the preferred types of chawan relates: "Raku first, Hagi second, Karatsu third."[9]

Another chawan type that became slightly popular during the Edo period from abroad was the Annan ware from Vietnam (Annam), which were originally used there as rice bowls. Annan ware is blue and white, with a high foot.

Usage

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

A cloth called chakin (茶巾) is used to wipe the bowl clean.

Normally the bowl would be wrapped in an orange turmeric-coloured cloth called ukon-nuno (ウコン布) for storage in the box, which apparently helps ward insects away.

A cloth bag shifuku (仕服) made out of silk or brocade can be used for storage of special tea bowls, especially for tenmoku chawan types. This is supported by four smaller cushions on each side inside the wooden box to help stabilise and protect the bowl. A more simpler cloth bag gomotsu-bukuro (御物袋) can also be used instead.

Shapes

[edit]Japanese chawan have various shapes and types, many of which have specific names:[10]

- Circle shape (鉄鉢形, Wa-nari)[11]

- Wooden bowl shape (椀形, Wan-nari)[12]

- Goki type (呉記型, Goki-gata)[13]

- Half cylinder shape (半筒型, Han tsutsu-gata)[14]

- Cylinder type (筒型, Tsutsu-gata)[15]

- Go stone box type (碁笥底型, Gokezoko-gata)

- Waist type (胴締, Dojimari-gata)[16]

- Rider's cup (馬上杯, Bajyohai)

- Cedar shape (杉形, Sugi-nari)[17]

- Ido or well type (井戸型, Ido-gata)[18][19]

- Tenmoku type (天目型, Tenmoku-gata)[20]

- Komogai shape (Komogai-nari)[21][18] – formerly imported from the Korean port of Ungcheon-dong now part of Changwon

- Curving lip type (端反り型, Hatazori-gata)

- Flat shape (平形, Hira-gata)[22]

- Horse bucket (馬盥, Badarai)

- Clog or shoe shape (沓形, Kutsu-gata)[23]

- Shoreline type (砂浜形, Suhama-gata)

- Peach shape (桃形, Momo-gata)

- Brush washer shape (筆洗形, Hissen-gata)[24]

- Straw hat (編笠, Amikasa)

- Triangular shape (三角形, Sankaku-gata)

- Four sided shape (四方形, Shiho-gata)

- Iron bowl (鉄鉢形, tetsubachi-nari / teppatsu-nari)[25]

- Silver tenmoku (銀天目茶碗, silver tea bowl made in the tenmoku style)

-

circle shape (鉄鉢形, Wa-nari)

-

Tenmoku type (天目型, Tenmoku-gata)

-

Ido or well type (井戸型, Ido-gata)

-

Komogai shape (Komogai-nari)

-

clog or shoe shape type (沓形, Kutsu-gata)

-

four sided shape type (四方形, Shiho-gata)

-

Black raku bowl used for thick tea, Azuchi-Momoyama period, 16th century

Foot

[edit]The foot (高台 Kōdai) of the Japanese chawan can be in various different shapes and sizes. The most known are:[26]

- Ring foot (輪高台, Wa Kōdai)

- Snake’s eye foot (蛇ノ目高台 or 普通高台, Janome or Futsū Kōdai)

- Double foot (二重高台, Nijū Kōdai)

- Crescent moon foot (三日月高台, Mikazuki Kōdai)

- Shamisen plectrum foot (撥高台, Bachi Kōdai)

- Bamboo node foot (竹節高台, Takenofushi Kōdai)

- Cherry blossom foot (桜高台, Sakura Kōdai)

- Four directions foot (四角高台, Shiho Kōdai)

- Go stone box foot (碁石高台, Gokezoko-Kōdai)

- Nail carved foot (釘彫高台, Kugibori Kōdai)

- Spiral shell foot (貝尻高台, Kaijiri Kōdai)

- Whirlpool foot (渦巻高台, Uzumaki Kōdai)

- Helmet foot (兜巾, Tokin Kōdai)

- Crinkled cloth foot (縮緬高台, Chirimen Kōdai)

- Split foot (割高台, Wari Kōdai)

- Cut foot (切高台, Kiri Kōdai)

- Two split foot (割一文字高台, Wariichimonji Kōdai)

- Bar cut foot (釘彫高台, Kiriichimonji Kōdai)

- Four split foot (割十文字高台, Warijūmonji Kōdai)

- Cross cut foot (切十文字高台, Kirijūmonji Kōdai)

-

Split foot (割高台, Wari Kōdai)

-

Cut foot (切高台, Kiri Kōdai)

-

Four split foot (割十文字高台, Warijūmonji Kōdai)

See also

[edit]- List of Japanese tea ceremony utensils

- Yunomi, teacups used in Japan for everyday use

References

[edit]- ^ Kodansha encyclopedia of Japan, Volume 2. Tokyo: Kodansha. 1983. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-87011-622-3.

- ^ "Jian ware". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Tsuchiya, Yoshio (2002). The fine art of Japanese food arrangement. London: Kodansha Europe Ltd. p. 67. ISBN 978-4-7700-2930-0.

- ^ "Tea bowl (China) (91.1.226)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010.

- ^ Bushell, S.W. (1977). Chinese pottery and porcelain. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580372-8.

- ^ a b Ono, Yoshihiro; Rinne, Melissa M. "Tenmoku Teabowls". Kyoto National Museum. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "일본국보사발은 왜 조선의 제기인가" (in Korean). 28 January 2004.

- ^ Sadler, A.L. Cha-No-Yu: The Japanese Tea Ceremony. Tokyo: Tuttle, 1962, 67.

- ^ "Veteran of Hagi continues rediscovery". 22 January 2000.

- ^ "Japanese Tea Bowl Shapes". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "鉄鉢形, Wa-nari: Circle Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "椀形, Wan-nari: Wooden Bowl Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "呉記型, Goki-gata: Goki Type Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "半筒型, Han tsutsu-gata: Half Cylinder Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "筒型, Tsutsu-gata: Cylinder Type Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "胴締, Dojimari-gata: Waist Type Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "杉形, Sugi-nari: Cedar Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ a b "Korean tea bowls imported to Japan" (in Japanese and English). Miho Museum.

- ^ "井戸型, Ido-gata: Ido or Well Type Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "天目型, Tenmoku-gata: Tenmoku Type Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "Komogai-nari: Komogai Shape Tea Bowls". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "平形, Hiragata: Flat Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "沓形, Kutsu-gata: Clog or Shoe Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "筆洗形, Hissen-gata: Brush Washer Shape Tea Bowls (抹茶茶碗)". flyeschool.com.

- ^ "Chado - Reviving History through a Cup of Tea". 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Japanese Tea Bowl Feet". flyeschool.com.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Chawan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chawan at Wikimedia Commons

- JNT, Joy of the Noble Teacup: International Chawan Exhibition

- Official page of an international traveling chawan Exhibition

- A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics from the Metropolitan Museum of Art