Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Celadon

View on Wikipedia| Celadon | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 青瓷 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 青瓷 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "blue-green porcelain" | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Celadon (/ˈsɛlədɒn/) is a term for pottery denoting both wares glazed in the jade green celadon color, also known as greenware or "green ware" (the term specialists now tend to use),[1] and a type of transparent glaze, often with small cracks, that was first used on greenware, but later used on other porcelains. Celadon originated in China, though the term is purely European, and notable kilns such as the Longquan kiln in Zhejiang province are renowned for their celadon glazes.[2] Celadon production later spread to other parts of East Asia, such as Japan and Korea,[3] as well as Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand. Eventually, European potteries produced some pieces, but it was never a major element there. Finer pieces are in porcelain, but both the color and the glaze can be produced in stoneware and earthenware. Most of the earlier Longquan celadon is on the border of stoneware and porcelain, meeting the Chinese but not the European definitions of porcelain.

For many centuries, celadon wares were highly regarded by the Chinese imperial court, before being replaced in fashion by painted wares, especially the new blue and white porcelain under the Yuan dynasty. The similarity of the color to jade, traditionally the most highly valued material in China, was a large part of its attraction. Celadon continued to be produced in China at a lower level, often with a conscious sense of reviving older styles. In Korea, the celadon produced during Goryeo period (918–1392) are regarded as classic wares of Korean porcelain.

The celadon color is classically produced by firing a glaze containing a little iron oxide at a high temperature in a reducing kiln. The materials must be refined, as other chemicals can alter the color completely. Too little iron oxide causes a blue color (sometimes a desired effect), and too much gives olive and finally black; the right amount is between 0.75% and 2.5%. The presence of other chemicals may have effects; titanium dioxide gives a yellowish tinge.[4]

Etymology

[edit]

The term "celadon" for the pottery's pale jade-green glaze was coined by European connoisseurs of the wares. The most commonly accepted theory is that the term first appeared in France in the 17th century and that it is named after the shepherd Celadon in Honoré d'Urfé's French pastoral romance L'Astrée (1627),[5] who wore pale green ribbons. (D'Urfé, in turn, borrowed his character from Ovid's Metamorphoses V.144.) Another theory is that the term is a corruption of the name of Saladin (Salah ad-Din), the Ayyubid Sultan, who in 1171 sent forty pieces of the ceramic to Nur ad-Din Zengi, Sultan of Syria.[6]

Production and characteristics

[edit]

Celadon glaze refers to a family of usually partly transparent but colored glazes, many with pronounced (and sometimes accentuated) "crackle", or tiny cracks in the glaze produced in a wide variety of colors, generally used on stoneware or porcelain pottery bodies.

So-called "true celadon", which requires a minimum 1,260 °C (2,300 °F) furnace temperature, a preferred range of 1,285 to 1,305 °C (2,340 to 2,380 °F), and firing in a reducing atmosphere, originated at the beginning of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127),[7] at least on one strict definition. The unique grey or green celadon glaze is a result of iron oxide's transformation from ferric to ferrous iron (Fe2O3 → FeO) during the firing process.[7][8] Individual pieces in a single firing can have significantly different colors, from small variations in conditions in different parts of the kiln. Most of the time, green was the desired color, reminding the Chinese of jade, always the most valued material in Chinese culture.

Celadon glazes can be produced in a variety of colors, including white, grey, blue and yellow, depending on several factors:

- the thickness of the applied glaze,

- the type of clay to which it is applied,

- the exact chemical makeup of the glaze,

- the firing temperature

- the degree of reduction in the kiln atmosphere and

- the degree of opacity in the glaze.

The most famous and desired shades range from a very pale green to deep intense green, often meaning to mimic the green shades of jade. The main color effect is produced by iron oxide in the glaze recipe or clay body. Celadons are almost exclusively fired in a reducing atmosphere kiln as the chemical changes in the iron oxide which accompany depriving it of free oxygen are what produce the desired colors.

East Asia

[edit]Chinese celadons

[edit]

Greenwares are found in earthenware from the Shang dynasty onwards.[4] Archaeologist Wang Zhongshu states that shards with a celadon ceramic glaze have been recovered from Eastern Han dynasty (AD 25–220) tomb excavations in Zhejiang, and that this type of ceramic became well known during the Three Kingdoms (220–265).[9] These are now often called proto-celadons, and tend to browns and yellows, without much green.

The earliest major type of celadon was Yue ware,[10] which was succeeded by a number of kilns in north China producing wares known as Northern Celadons, sometimes used by the imperial court. The best known of these is Yaozhou ware.[11] All these types were already widely exported to the rest of East Asia and the Islamic world.

Longquan celadon wares were first made during the Northern Song, but flourished under the Southern Song, as the capital moved to the south and the northern kilns declined.[12] This had bluish, blue-green, and olive green glazes and the bodies increasingly had high silica and alkali contents which resembled later porcelain wares made at Jingdezhen and Dehua rather than stonewares.[13]

All the wares mentioned above were mostly in, or aiming to be in, some shade of green. Other wares which can be classified as celadons, were more often in shades of pale blue, very highly valued by the Chinese, or various browns and off-whites. These were often the most highly regarded at the time and by later Chinese connoisseurs, and sometimes made more or less exclusively for the court. These include Ru ware, Guan ware and Ge ware,[14] as well as earlier types such as the "secret color" (mi se) wares,[15] finally identified when the crypt at the Famen Temple was opened.

Large quantities of Longquan celadon were exported throughout East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East in the 13th–15th century. Large celadon dishes were especially welcomed in Islamic nations. Since about 1420 the Counts of Katzenelnbogen have owned the oldest European import of celadon, reaching Europe indirectly via the Islamic world. This is a cup mounted in metal in Europe, and exhibited in Kassel in the Landesmuseum.[16] After the development of blue and white porcelain in Jingdezhen ware in the early 14th century, celadon gradually went out of fashion in both Chinese and export markets, and after about 1500 both the quality and quantity of production was much reduced, though there were some antiquarian revivals of celadon glazes on Jingdezhen porcelain in later centuries.[17]

Decoration in Chinese celadons is normally only by shaping the body or creating shallow designs on the flat surface which allow the glaze to pool in depressions, giving a much deeper color to accentuate the design. In both methods carving, moulding and a range of other techniques may be used. There is very rarely any contrast with a completely different color, except where parts of a piece are sometimes left as unglazed biscuit in Longquan celadon.

-

Yaozhou ware (Northern Celadon), with carved and engraved decoration, 10th century.

-

Yaozhou ware, Shaanxi province, Song dynasty, 10th–11th century

-

Centre areas left unglazed in 'biscuit state', 14th century.

-

Warming Bowl in the Shape of a Flower with Light Bluish-green Glaze, Ru ware

-

Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 1100s–1200s AD

-

Flower vase with Iron Brown Spots (飛青磁花生), Longquan kiln, Yuan dynasty, 13–14th century (National Treasure)

-

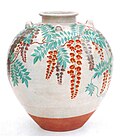

Longquan celadon from Zhejiang, Ming dynasty, 14–15th century

-

Ewer, lidded tripod with handles, used for heating certain alcoholic drinks. Stoneware with pale green (celadon) glaze. Six Dynasties, 500-580 CE. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Japanese celadons

[edit]

The Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters for greenware is seiji (青磁). It was introduced during the Song dynasty (960–1270) from China and via Korea. Even though Japan has arguably the most diverse styles of ceramic art in the modern era, greenware was mostly avoided by potters because of the high loss rate of up to 80%.[18] Kaolinite, the ceramic material usually used for the production of porcelain, also does not exist in large quantities like in China. One of the sources for kaolin in Japan is from Amakusa in Kyushu. Nevertheless, a number of artists emerged whose works received critical acclaim in regards to the quality and color of the glazes achieved, as well as later on in the innovation of modern design.

Three pieces originally from China have been registered by the government as national treasures. They are two flower vases from the Longquan kiln dating to the southern Song dynasty in the 13th century, and a flower vase with iron brown spots also from Longquan kiln dating to the Yuan dynasty in the 13–14th century.

Production in the style of Longquan was centered around Arita, Saga and in the Saga Domain under the lords of the Nabeshima clan.[19] Greenware is also closed entwined with hakuji (白磁) white porcelain. The glaze with a mixed subtle color gradations of icy, bluish white is called seihakuji (青白磁) porcelain.[20] In Chinese this type of glaze is known as Qingbai ware.[21] Qingbai's history goes back to the Song dynasty. It is biscuit-fired and painted with a glaze containing small amounts of iron. This turns a bluish color when fired again. Japanese artists and clients tend to favor the seihakuji bluish white glaze over the completely green glaze.[19]

Pieces that are produced are normally tea or rice bowls, sake cups, vases, and plates, and mizusashi water jars for tea ceremony, censers and boxes. Some post-modern ceramic artists have however expanded into the area of sculpture and abstract art as well.

Artists from the early Showa era are Itaya Hazan (1872–1963), Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886–1963), Kato Hajme (1900–1968), Tsukamoto Kaiji (塚本快示) (1912–1990), and Okabe Mineo (1919–1990), who specialized in Guan ware with its crackled glaze. Tsukamoto Kaiji was nominated a Living National Treasure in 1983 for his works in seihakuji. Artists from the mid- to late Showa era were Shimizu Uichi (1926–?), who also specialized in crackled glaze, Suzuki Osamu (1926–2001), Miura Koheiji (1933–?),[18] Suzuki Sansei (b. 1936), Fukami Sueharu (b. 1947), and Takenaka Ko (b. 1941). During the Heisei era artists are Masamichi Yoshikawa (b. 1946),[22] Kawase Shinobu (b. 1950),[23] Minegishi Seiko (b. 1952),[24] Kubota Atsuko (b. 1953), Yagi Akira (b. 1955) and Kato Tsubusa (加藤委) (b. 1962).

Artists such as Fukami Sueharu, Masamichi Yoshikawa, and Kato Tsubusa also produce abstract pieces, and their works are part of a number of national and international museum collections.[25] Kato Tsubusa works with kaolin from New Zealand.[26]

Korean celadons

[edit]

Korean celadon has its own tradition of greenware production, dating back to the Three Kingdoms period. Korea has a tradition of making jewels and crowns with jade in gogok shapes as a symbol of creativity, universe, divinity, and leadership. Chinese greenwares inspired local potters as well. Exceptional high-quality celadons were produced in Korea during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties.[27] An inlaid greenware technique known as sanggam, where potters would engrave semi-dried pottery with designs and place black or white clay materials within the engraving, was invented in Korea during this time.[27][28][29]

Korean greenware, also known as "Goryeo celadon" is usually a pale green-blue in color. The glaze was developed and refined during the 10th and 11th centuries during the Goryeo period, from which it derives its name. Korean greenware reached its zenith between the 12th and early 13th centuries, however, the Mongol invasions of Korea in the 13th century and persecution by the Joseon dynasty government destroyed the craft.[citation needed]

The Gangjin Kiln Sites produced a large number of Goryeo wares and were a complex of 188 kilns. The kiln sites are located in Gangjin County, South Jeolla Province near the sea. Mountains in the north provided the necessary raw materials such as firewood, kaolin and silicon dioxide for the master potters while a well established system of distribution transported pottery throughout Korea and facilitated export to China and Japan. The sites are tentatively listed as a World Heritage by the South Korean government. Celadon was used as a "spirit vessel" or Chy- Tang to summon spirits to bring positivity, in many Korean temples from the 14th century.

Traditional Korean greenware has distinctive decorative elements. The most distinctive are decorated by overlaying glaze on contrasting clay bodies. With inlaid designs, known as sanggam in Korean, small pieces of colored clay are inlaid in the base clay. Carved or slip-carved designs require layers of a different colored clay adhered to the base clay of the piece. The layers are then carved away to reveal the varying colors.

A number of items dating from the Goryeo dynasty have been registered by the government as a National Treasure of South Korea, such as a Dragon kettle from the 12th century (National Treasure No. 61), a maebyeong vase with sanggam engraved cranes (National Treasure No. 68), an elaborate censer with kingfisher glaze (National Treasure No. 95), and a pitcher in the shape of a Dragon Turtle (National Treasure No. 96).

Beginning in the early 20th century, potters, using modern materials and tools, attempted to recreate the techniques of ancient Korean Goyeo celadons. Playing a leading role in its revival was Yu Geun-Hyeong (유근형; 柳根瀅), a Living National Treasure whose work was documented in the 1979 short film, Koryo Celadon. Another notable potter and Living National Treasure was Ji Suntaku (1912–1993). Today, hundreds of potters showcase their work at the Icheon Ceramics Village, which features contemporary work from Sugwang-ri, Sindun-myeon, and Saeum-dong, Icheon.[30]

In the late 20th century ceramists like Shin Sang-ho and Kim Se-yong created their own styles based upon traditional Goryeo ware. Kim came to prominence for his double-openwork his highly detailed which sometimes featured more than 1500 individually formed chrysanthemum flowers.[31]

The National Museum of Korea in Seoul houses important celadon works and national treasures. The Haegang Ceramics Museum and the Goryeo Celadon Museum are two regional museums that focus on Korean greenware.

-

Dragon turtle kettle, Goryeo dynasty, 12th century (National Treasure No. 61)

-

Maebyeong vase with sanggam engraved cranes, hand carved 12th century Goryeo dynasty, (National Treasure No. 68)

-

Goryeo dynasty bowl with sanggam inlay

-

Goryeo celadon incense burner with Girin mystic sacred animal lid on it

-

Goryeo celadon of Korean Chamoe (yellow water melon) shaped motif, 12th century

-

tea cup with flower inlays, Goryeo dynasty

-

horibyeong, Korea celadon of Goryeo period

-

creative design of baby bamboo, virtue for scholars, water dropper for calligraphy, Seoye

-

Goryeo celadon ewer or tea pot inside a cup

-

a step to the white porcelain, Goryeo celadon

-

Pitcher in the shape of a Dragon Turtle, Goryeo dynasty, (National Treasure No. 96)

-

inlay carved tea cup with silver lining, Goryeo celadon

-

incense burner, Goryeo Celadon

-

incense burner of Goryeo, celadon

-

pillow, celadon example of Goryeo period single-wall openwork

-

celadon hand-carved inlaid and colored red, decorated with grapes

-

Goryeo incense keeping case hand carved and inlaid with white and black, white cranes decorated

-

Korea Goryeo dynasty object of a seated immortal

-

Korean water melon Chamowe shape tea pot or ewer became popular

-

Celadon openwork chairs, objects for calligraphy ceremony Seoye

-

lighter glazed tea cup Goryeo celadon, incised parrot

-

celadon vase, Goryeo period

-

aromatic oil container with four other incense boxed

-

molded and carved lotus, Gangjin kilns, 1100–1250 celadon

-

face washing plate called sesoodaeya, Goryeo celadon

-

Lidded Jar, Joseon dynasty (National Treasure No. 1071)

-

Goryeo celadon incense burner with duck lid on, 12th century, duck symbolizes a sacred guide to the sky on the way across a hwangcheon river after death

Southeast Asia

[edit]Thai celadon

[edit]Thai ceramics has its own tradition of greenware production. Medieval Thai wares were initially influenced by Chinese greenware, but went on to develop its own unique style and technique. One of the most famous kilns during the Sukhothai Kingdom were at S(r)i Satchanalai, around Si Satchanalai District and Sawankhalok District, Sukhothai Province, north-central Thailand. Production started in the 13th century CE and continued until the 16th century. The art reached its apex in the 14th century.[32]

-

Bowl with incised peony designs, Sri Satchanalai, 15th century

-

Bottle with two shoulder lugs, Sawankhalok, 15th century

Vietnamese celadon

[edit]-

Teapot, Lý dynasty period, 11th–12th century

-

Tea cup, Lý dynasty period, 11th–12th century

-

Green celadon jar, Trần dynasty period, 14th century

Others

[edit]

Outside of East Asia, a number of artists also worked with greenware to varying degrees of success in regard to purity and quality. These include Thomas Bezanson of Weston Priory in the US and Wanda Golakowska (1901–1975) of Poland, whose works are part of the collection of the National Museum, Warsaw and National Museum, Kraków.

Citations

[edit]- ^ British Museum glossary; Christie's Collector's Guide; this is not to be confused with "greenware", meaning unfired clay pottery, as a stage of production.

- ^ "Chinese Porcelain Glossary: Celadon". Gotheborg.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Goryeo Celadon | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ a b Vainker, S. J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Press, pp. 53–55, ISBN 9780714114705.

- ^ Gompertz, 21

- ^ Dennis Krueger. "Why On Earth Do They Call It Throwing?" Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine from Ceramics Today

- ^ a b Dewar, Richard. (2002). Stoneware. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1837-X, p. 42.

- ^ Hagras, Hamada (2022-01-01). "Chinese Islamic Ceramics at the Museum of Niujie Mosque "An analytical Study"". مجلة کلية الآثار . جامعة القاهرة. 12 (2022): 319–341. doi:10.21608/jarch.2022.212076. ISSN 1110-5801.

- ^ Wang, Zhongshu. (1982). Han Civilization. Translated by K.C. Chang and Collaborators. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02723-0.

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 1

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 4

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 6

- ^ Wood, Nigel. (1999). Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3476-6, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 4 and 5

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 3

- ^ "Katzenelnbogener Weltrekorde: Erster RIESLING und erste BRATWURST!". Graf-von-katzenelnbogen.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ Gompertz, Ch. 7 & 8

- ^ a b "CELADON Menu – EY Net Japanese Pottery Primer". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ a b "Ambient Green Flow _ 青韻流動". Exhibition.ceramics.ntpc.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "PORCELAIN Menu – EY Net Japanese Pottery Primer". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ ""Pure-pure" Seihakuji bowl | Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art". Museum.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

- ^ "Yoshikawa Masamichi – Artists – Joan B Mirviss LTD | Japanese Fine Art". Mirviss.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Kawase Shinobu, Japanese Celadon Artist". E-yakimono.net. 2000-04-19. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Minegishi Seiko, Celadon Artist from Japan". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Collection | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Kato Tsubusa – White Porcelain Artist". E-yakimono.net. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ International, Rotary (December 1988). The Rotarian. p. 15. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ Rose Kerr; Joseph Needham; Nigel Wood (2004-10-14). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical …. Cambridge University Press. p. 719. ISBN 9780521838337. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ "Icheon Ceramics Village (이천도예마을)". VisitKorea.or.kr. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ Seong, Chang-hee. "Sechang master Kim Se-yong, life and soul captured in celadon for 50 years... Ceramic art blooms [명장을 찾아서] 세창 김세용 명장, 50년 청자에 담은 삶과 혼…도자예술 꽃 피우다:동아경제". www.daenews.co.kr. Retrieved 2024-04-19.

- ^ Roxanna M. Brown: The Sukhothai and Sawankhalok Kilns. In: Dies.: The Ceramics of South-East Asia: Their Dating and Identification. 2nd edition. Art Media Resources, Chicago, 2000, ISBN 1-878529-70-6, S. 56–80.

General and cited references

[edit]- Gompertz, G. St. G. M., Chinese Celadon Wares, 1980 (2nd ed.), Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571180035.

Further reading

[edit]- Yong-i Yun; Regina Krahl. Korean Art from the Gompertz and Other Collections in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

- Valenstein, Suzanne G. (1975): A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

External links

[edit]Celadon

View on GrokipediaEtymology and History

Etymology

The term "celadon" originates from the French word céladon, referring to a pale grayish-green color first recorded in English in 1768. It derives from the name of the character Céladon, a shepherd in Honoré d'Urfé's 17th-century pastoral romance L'Astrée (published 1607–1627), who was often depicted wearing attire in soft green tones, including ribbons and a coat of that hue. The character's name itself traces back to the Greek Keladôn from Ovid's Metamorphoses, possibly meaning "sounding with din or clamor," though this etymology pertains more to the literary figure than the color association.[4][1] In the 18th century, European collectors and connoisseurs began applying "celadon" to describe imported East Asian ceramics featuring a jade-like green glaze, with the first known use for such pottery dating to 1763. Initially, the term was used broadly in Europe to encompass various green-glazed wares, regardless of precise composition or origin, reflecting the exotic appeal of these imports from China that reached European markets via trade routes. Over time, however, its meaning refined to denote specifically the high-fired stoneware with a translucent, crackled jade-green glaze, distinguishing it from other green ceramics.[4][3] Unlike the broader Chinese term qingci (青瓷), which translates to "green porcelain" or "greenware" and applies to any high-temperature glazed ceramics in green tones dating back to ancient prototypes, "celadon" as adopted in the West emphasizes the aesthetic and technical qualities of East Asian traditions, particularly those from the Song dynasty onward. This European nomenclature highlights a cultural lens on the pottery's color rather than its production methods, though some scholars critique it as a romanticized misnomer for qingci.[5][1]Origins and Early Development

Celadon ware originated in China during the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE), with early examples produced at the Yue kilns in Zhejiang province. These pieces marked the development of proto-porcelain stoneware bodies coated in iron-rich glazes, which, when fired in a reduction atmosphere, yielded the distinctive pale green color associated with celadon. The Yue kilns, located near Shanglin Lake, produced fine gray stoneware vessels with subtle olive-green glazes that often exhibited natural crackling due to the glaze's contraction during cooling.[6][7][8] The craft reached its artistic zenith during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), particularly through the Longquan kilns in southern Zhejiang, where celadon production flourished under imperial patronage. Emperors such as Huizong actively supported ceramic innovation, commissioning wares that emphasized jade-like translucency and refined crackle patterns in the glaze, symbolizing harmony and natural beauty in Song aesthetics. Longquan celadons, often in simple forms like bowls and ewers, became prized for their even, ice-crackled surfaces and subtle color variations from grayish-green to bluish tones, reflecting advancements in kiln control and glaze formulation.[9][10][11] Celadon's influence spread rapidly via the Silk Road overland routes and maritime trade networks, with exports reaching the Middle East by the 9th century, where fragments have been excavated at sites like Samarra in Iraq and Fustat in Egypt, inspiring local Islamic potters to imitate the green glazes. By the 10th century, the technology had been introduced to Korea, where prototypes appeared late in the century, as evidenced by dated pieces from 993 CE that adapted Chinese techniques to local stoneware.[6][12][13] After the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 CE), celadon's prominence in China waned domestically due to the rising popularity of blue-and-white porcelain, which gained favor for its vibrant underglaze decoration using cobalt imported via trade routes. Nonetheless, celadon persisted as a key export commodity, maintaining production at sites like Longquan for international markets into the Ming period.[6][14]Characteristics and Production

Glaze Composition and Properties

Celadon glazes are primarily feldspathic in composition, consisting of a base mixture of feldspar, silica (SiO₂), and lime (CaO) as key fluxing agents, applied over a stoneware or porcelain body.[15] The addition of iron oxide (Fe₂O₃) at concentrations typically ranging from 0.2% to 3% serves as the primary chromophore, with lower levels producing pale greens and higher amounts yielding deeper tones.[16][17] This iron content, often derived from natural impurities in the raw materials, is crucial for the glaze's characteristic coloration.[18] The signature green hues of celadon arise from the reduction firing process, which alters the oxidation state of iron from Fe³⁺ (in Fe₂O₃) to Fe²⁺, absorbing certain wavelengths of light to create jade-like green tones.[19] In contrast, oxidation firing maintains higher Fe³⁺ levels, resulting in brownish shades rather than the desired greens.[20] The Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ ratio, influenced by the controlled reduction atmosphere, directly impacts the intensity and subtlety of the color, with higher ratios producing more bluish-green tones.[19] These glazes exhibit translucency due to their thin to moderate application, allowing the underlying body to subtly influence the overall appearance.[21] A common surface feature is crackle or crazing, resulting from thermal expansion mismatch between the glaze and body, where the glaze contracts more rapidly upon cooling; this is often enhanced by high sodium and potassium content from the feldspar. Such crazing contributes to the textured, aged aesthetic valued in traditional celadons.[21] Variations in celadon glazes occur within firing temperatures of 1200–1300°C, where subtle impurities in the clay or raw materials, such as titania, can shift colors toward blues or grays.[21][22] Modern analysis of these glazes frequently employs X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy to quantify iron content and other elemental compositions, confirming the low iron levels (under 2 wt%) essential for authentic green development.[23][18]Firing Techniques and Forms

Celadon production traditionally relies on specialized kiln designs that facilitate high-temperature firing while accommodating large-scale output. In China, dragon kilns, also known as climbing kilns, were pivotal for high-volume production, featuring elongated, multi-chambered structures built along slopes to utilize natural draft for efficient heat distribution and continuous firing.[24] These kilns, often fueled by wood, allowed potters to fire thousands of pieces simultaneously, contributing to the widespread dissemination of celadon wares during peak production periods. In Japan, similar principles informed the nobori-gama, a multi-chamber climbing kiln that influenced celadon firing among select potters, emphasizing controlled flame paths for varied atmospheric effects.[25] The firing process for celadon emphasizes a wood-fired reduction atmosphere to enhance the glaze's subtle hues and textures, typically lasting 12 to 24 hours or longer in traditional setups. Potters load bisque-fired vessels into the kiln, often using saggars—refractory boxes—to stack pieces securely and prevent glaze runs from dripping ash or molten material during the intense heat, which reaches 1,250–1,350°C.[26][27] The reduction environment, created by limiting oxygen through controlled wood combustion, interacts with trace iron in the glaze to produce the characteristic jade-like finish, while periodic stoking maintains temperature zones for differential effects.[28] In Longquan celadon traditions, this process involves a multi-stage cycle of heating and cooling to ensure even vitrification without cracking.[29] Common forms of celadon include utilitarian and decorative objects such as bowls, vases, ewers, and architectural tiles, shaped on wheels or molds for symmetry and functionality. Decorations are typically applied before glazing, featuring incised or molded motifs like peonies, which symbolize prosperity and are carved into the unfired clay surface to create subtle reliefs that catch light post-firing. These forms prioritize elegance and balance, with ewers often featuring spout and handle integrations inspired by metalwork, while tiles served practical roles in building facades or pavements.[30] Quality control in celadon firing centers on achieving the prized "moon in water" effect, a poetic term for the glaze's soft, reflective sheen that evokes elusive lunar glows on liquid surfaces, resulting from precise reduction and cooling to minimize imperfections.[31] Artisans inspect for defects such as pinholes, caused by gas bubbles from organic residues or carbonates escaping during firing and failing to heal in the molten glaze, which can compromise the surface's integrity if not addressed through refined clay preparation or extended soaks.[32] Techniques evolved significantly with the introduction of ash glazes during the Song era (960–1279 CE), where wood ash flux was incorporated to yield natural variations in texture and subtle crackling, enhancing the organic interplay between fire and material beyond earlier uniform finishes.[33] This innovation, combined with refined kiln management, allowed for greater aesthetic diversity while maintaining the reduction atmosphere's role in color development through iron's subtle influence.[29]East Asian Traditions

Chinese Celadon

Chinese celadon production flourished during the Song dynasty (960–1279), with key kilns emerging in northern and southern China that defined imperial and elite aesthetics. The Ru kilns, located in Qingliangsi village, Baofeng County, Henan province, operated primarily in the late 11th century under imperial patronage, yielding rare stoneware pieces coated in a subtle, sky-blue celadon glaze often exhibiting fine crackle patterns. These wares, produced in limited quantities for the court, represent the pinnacle of northern celadon refinement, with only about 60 authentic examples known to survive today.[34][35] In contrast, the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang province, particularly around Dayao and Jincun, expanded dramatically from the Southern Song period onward, reaching their peak output in the 13th–14th centuries during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). These southern kilns supported widespread production of durable, jade-like green-glazed stoneware, enabling the creation of large-scale vessels and facilitating extensive maritime trade to regions including the Middle East.[6][36] Distinct stylistic variations characterized Chinese celadon, reflecting regional techniques and artistic preferences. Ge ware, associated with kilns near Hangzhou, featured intentional fine and coarse crackle glazes in grayish-green tones, prized for their textured, ice-like appearance that evoked natural imperfections. Guan ware, produced at imperial kilns in the same area, offered smoother, more even opalescent glazes in pale blue-green hues, often with subtle crackling that enhanced the serene, jade-emulating surface. Decorative motifs commonly included raised relief designs of dragons symbolizing imperial power or floral elements like peonies representing prosperity, incised or molded directly into the clay before glazing.[37][38][39] Celadon held profound cultural significance in China, its jade-like translucency symbolizing purity, harmony with nature, and immortality—qualities long attributed to jade in Confucian and Daoist traditions. Valued for these associations, celadon vessels were integral to Song dynasty tea ceremonies, where their subtle green tones complemented the frothy whisked tea favored by elites, fostering rituals of mindfulness and social refinement. In funerary contexts, Longquan celadons were commonly interred in tombs to provision the afterlife, as seen in burial jars containing grains for ancestral rites. During the Yuan dynasty, imperial policies spurred mass production at Longquan, with higher alumina bodies allowing for larger forms; historical records indicate that up to 80% of exported ceramics were celadons, shipped via coastal ports to Southeast Asia, the Islamic world, and beyond, underscoring their role in Silk Road commerce.[40][41][42][43][44][45] Following the Yuan, celadon production declined sharply after the 14th century as Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province rose to dominance with underglaze blue-and-white porcelain, which captured export markets and imperial favor due to its vibrant decoration and translucency. By the 16th century, many Longquan kilns had ceased operations, shifting focus to painted wares amid Ming dynasty innovations. A revival occurred in the 20th century, particularly post-1949, when Longquan artisans resumed traditional techniques amid cultural heritage initiatives, producing modern interpretations that echo Song-Yuan aesthetics while incorporating contemporary forms. A notable surviving artifact is the British Museum's Ru ware bowl from the Northern Song dynasty (dated 1086–1125), featuring a lavender-blue celadon glaze with fine crackle and an imperial inscription praising its rarity and virtuous symbolism.[6][46][47][34]Korean Celadon

Celadon ceramics were introduced to Korea from China during the early Goryeo dynasty (918–1392 CE), with production beginning in the 11th century and rapidly evolving into a distinctly Korean art form.[1][30] By the mid-12th century, celadon reached its peak, becoming the primary ceramic type on the peninsula, with major kilns concentrated in Jeollanam-do province, particularly at Gangjin, where archaeological evidence reveals extensive firing sites and waster deposits indicating large-scale output.[1][48] These innovations distinguished Korean celadon from its Chinese prototypes through refined techniques and aesthetics tailored to Goryeo's Buddhist-influenced elite culture.[30] A signature innovation was the sanggam inlay technique, unique to Goryeo celadon, where potters carved designs into the unfired clay body—often motifs like cranes, clouds, peonies, or auspicious symbols—then filled the incisions with white and black slips for contrast, applied a translucent glaze, and fired the piece in a reducing atmosphere at temperatures up to 1150°C.[1] This method produced intricate, almost incised-like decorations that enhanced the vessels' elegance without relying on painted slips common in Chinese wares.[48] The resulting glaze achieved a lighter, more translucent "kingfisher" green hue—a soft gray-green tone derived from iron content in the local clay and glaze—prized for its jade-like luster and subtlety, evoking natural beauty over the denser greens of Chinese celadons.[1][30] Korean celadons served primarily as ritual vessels for Buddhist monasteries and refined tableware for the aristocracy, reflecting Goryeo's devout Buddhism and Confucian-influenced court life; forms included ewers, bottles, and bowls adorned with symbolic imagery promoting harmony and longevity.[1] A renowned example is the 12th-century maebyeong (plum vase) in the National Museum of Korea, featuring sanggam inlays of clouds, cranes, and children at play, exemplifying the period's masterful balance of form and decoration.[1][30] Production declined sharply in the 13th century following Mongol invasions (1231–1259 CE), which disrupted kiln operations, displaced artisans, and shifted resources toward military needs, leading to coarser wares and eventual abandonment of major sites by the dynasty's end.[1][48] During the subsequent Joseon dynasty (1392–1910 CE), there was a brief revival of celadon techniques, but preferences evolved toward undecorated white porcelain as the new standard for elite ceramics, relegating celadon to lesser use.[1]Japanese Celadon

Celadon techniques were introduced to Japan from Korea during the 13th century, with Goryeo dynasty imports influencing early Japanese ceramics through trade and cultural exchange.[30] During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), these imported pieces, prized for their jade-like green glazes, inspired local adaptations, leading to production at major kiln sites such as Seto and Tokoname in Aichi Prefecture.[49] Seto kilns, active since the 13th century, began replicating celadon glazes on stoneware forms, marking the start of sustained domestic output.[50] A prominent style emerged in Tokoname during the 17th century, featuring ash-based glazes that produced subtle green tones through the interaction of iron content and high-temperature firing.[51] These glazes, applied over iron-rich clay bodies, created distinctive natural variations, differing from the low-fired, matte finishes of Raku ware while sharing a utilitarian ethos suited to everyday and ceremonial use.[52] In Japanese tea culture, known as chanoyu, celadon vessels became integral, embodying wabi-sabi aesthetics through intentional imperfections such as ash drips and uneven glazing that evoke transience and humility.[53] Post-World War II, potters like Hamada Shōji spearheaded a revival of traditional techniques, incorporating celadon glazes into modern folk pottery at sites like Mashiko while drawing on Seto and Tokoname legacies.[54] Contemporary Seto kilns continue this tradition, producing celadon pieces for both domestic markets and international export, often emphasizing sustainable wood-firing methods to achieve authentic green hues. A notable example is the 16th-century Karatsu celadon dish held in the Tokyo National Museum, showcasing early regional adaptations with its subtle ash-glazed surface and simple form.[55]Southeast Asian Adaptations

Vietnamese Celadon

Vietnamese celadon production began as early as the 5th–6th centuries CE at sites like Dai Lai and Gia Luong in Bac Ninh Province, but flourished during the Ly dynasty (1009–1225 CE), with kilns concentrated in the Red River Delta region. These early wares were heavily influenced by Song dynasty Chinese ceramics, adopting techniques for green-glazed stoneware, but incorporated local fine-grain off-white clay bodies to create distinct forms such as covered urns and inlaid decorations. Earlier sites like Tam Tho in Thanh Hoa province produced green-glazed stoneware from the 1st–3rd centuries CE.[56][57] Production reflected a blend of imported technology and indigenous adaptation, marking the beginning of a vibrant ceramic tradition in northern Vietnam.[56] The style reached its peak during the Le dynasty (1428–1789 CE), particularly at the Bat Trang kilns near Hanoi, where potters produced sophisticated wares featuring incised lotus motifs and other floral designs carved into the clay before glazing. These pieces typically employed transparent green celadon glazes, often exhibiting brown edges or bases resulting from oxidation during firing, alongside chocolate-brown slips for contrast. Bat Trang became a major center for high-quality stoneware, including bowls, dishes, and vases that showcased technical refinement and aesthetic innovation.[56] Vietnamese celadon played a significant role in regional trade, with exports reaching ports across Southeast Asia, including Cham territories, and finding use in imperial courts and Buddhist temples for ceremonial and decorative purposes. Wares from northern kilns influenced local productions in neighboring regions and were distributed as far as Japan and the Middle East, underscoring Vietnam's position in maritime networks.[56] In the 20th century, following colonial rule, Vietnamese celadon experienced a revival, particularly at enduring sites like Bat Trang, where production shifted toward tourism-oriented items blending traditional techniques with modern designs. A notable artifact exemplifying early mastery is an 11th–14th century ewer from the Ly-Tran period, featuring brown and celadon glazes, housed in Hanoi's National Museum of Vietnamese History.[58]Thai Celadon

Thai celadon production emerged in the 14th century at the Ban Ko Noi kilns in the Sukhothai kingdom (1238–1438 CE), where local potters created green-glazed stoneware vessels drawing inspiration from Chinese Longquan celadons imported through regional trade routes.[59] These early wares were fired in dragon kilns along the Yom River, utilizing local iron-rich clays to produce durable, high-fired stoneware that marked Thailand's entry into celadon craftsmanship.[60] Archaeological excavations have uncovered hundreds of kilns at sites like Ban Ko Noi and Ban Pa Yang, confirming sustained output from the mid-14th to 16th centuries, with pieces exported across Southeast Asia via maritime networks.[61] During the Ayutthaya kingdom (1351–1767 CE), Chinese influence intensified through extensive trade, as Ayutthaya served as a hub for porcelain imports and re-export, prompting Thai artisans to refine celadon techniques with local adaptations.[62] This period saw the integration of celadon into Ayutthaya's economy, with kilns producing wares that blended imported aesthetics and indigenous forms, such as ewers and dishes, to meet demand in royal courts and international markets.[63] Signature features of Thai celadon include thick, celadon-green glazes applied over buff-colored stoneware bodies, often developing distinctive crackle patterns due to the glaze's composition and cooling process; these glazes were achieved using ash-based fluxes and fired at temperatures around 1200–1300°C. Motifs frequently incorporated incised or molded designs like floral patterns or mythical elements, including naga serpents symbolizing protection in Buddhist iconography, particularly on vessels intended for temple offerings.[64] A prominent example is a 15th-century pear-shaped vase from the Si Satchanalai kilns, housed in the National Museum in Bangkok, which exemplifies the era's elegant forms and glossy, subtly crackled surface.[65] In Theravada Buddhist contexts, Thai celadon served as ritual vessels for offerings, such as water jars and bowls placed in temples to symbolize purity and merit-making, often alongside celadon-like Sawankhalok stoneware from the same kiln complexes.[63] These wares were valued for their serene green hue, evoking natural elements aligned with Buddhist cosmology, and were commonly used in monastic ceremonies or as dedicatory gifts. The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a revival of celadon production under the patronage of King Rama V (r. 1868–1910), who promoted traditional crafts amid modernization efforts, leading to renewed interest in ancient techniques.[66] Contemporary kilns in Ratchaburi continue this legacy, employing wood-fired methods to produce export-oriented pieces that echo historical styles while incorporating modern refinements for durability and aesthetics.[67]Global Influences and Modern Developments

Celadon in Other Regions

Chinese celadon reached East Africa through 14th–15th century Indian Ocean trade, with archaeological evidence from sites like Kilwa and Gedi in Kenya and Zanzibar in Tanzania revealing Longquan celadon sherds used in elite Swahili households and tombs. These imports, valued for their jade-like quality, influenced local ivory and beadwork aesthetics but did not lead to widespread imitation due to technological differences.[68]Middle East

Chinese celadon wares reached the Middle East through maritime trade routes along the Persian Gulf and Red Sea during the 9th to 12th centuries, arriving in Persia and inspiring local production at sites like Samarra in Iraq.[6] These imports, primarily from Tang and Song dynasty kilns, were valued for their jade-like green glazes and were distributed via Abbasid ports such as Basra and Siraf, where Muslim merchants facilitated exchange with Chinese traders.[69] At Samarra, the Abbasid capital under Caliph Al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842 CE), excavations have uncovered fragments of Chinese celadon alongside Iraqi imitations, highlighting the site's role as a hub for ceramic innovation blending Eastern aesthetics with Islamic motifs.[70] Abbasid potters developed imitations using alkaline glazes tinted with copper to achieve turquoise or bluish-green hues, closely mimicking the subtle jade tones of Chinese celadon while adapting forms like open bowls for local use.[71] These recreations, often on fritware bodies, emerged around the 9th century in Iraq and spread to Persia and Egypt, where potters at Fustat produced green-glazed vessels detected in archaeological contexts dating to the 10th–12th centuries.[72] The turquoise variants, in particular, reflected technological adaptations to available materials, with copper oxide providing the color under reducing kiln atmospheres, and were prized for their perceived ability to detect poison—a belief rooted in Chinese lore transmitted via trade.[73] This emulation extended Islamic ceramic traditions, filling a gap in high-fired stoneware production and influencing later Ilkhanid and Timurid wares in Persia.[6]South Asia

Celadon arrived in South Asia through 14th-century maritime trade networks connecting Chinese ports to Indian coastal regions, with archaeological evidence from Gujarat ports like Cambay and sites along the Malabar Coast revealing Longquan celadon sherds integrated into elite households and temple rituals.[74] These imports, shipped via the Indian Ocean from Zhejiang Province kilns, included high-quality green-glazed ceramics that fueled exchange amid the Delhi Sultanate's expansion, often traded alongside spices and textiles.[75] Under Mughal rule from the 16th century, these influences merged with Persian aesthetics, leading to green-glazed ceramics that echoed celadon's subtlety in imperial workshops at Lahore and Agra.[6] Mughal potters, drawing on earlier trade traditions, experimented with copper-tinted glazes on earthenware, producing vessels for courtly use that blended Indo-Islamic motifs with the serene jade tones of imported prototypes.[76] This synthesis, evident in 17th-century pieces from Rajasthan and Gujarat, underscored celadon's role in elevating local pottery to luxury status within the empire's vast trade networks.[6]Europe

In 19th-century Europe, British factories like Minton in Staffordshire revived celadon styles using lead glazes to replicate the translucent greens of Asian originals, with production peaking in the 1860s under designer Leon Arnoux.[77] Minton's majolica line incorporated celadon-inspired hues through vibrant, semi-translucent lead-based formulas fired at lower temperatures, applied to earthenware forms mimicking Chinese bowls and vases for the Victorian market.[78] These imitations, showcased at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, blended historicist revival with industrial techniques, achieving a glossy jade effect prized in middle-class homes.[79] The Art Nouveau movement around 1900 further adapted celadon in France and Austria, where designers at Amphora in Vienna used soft green glazes on organic-shaped porcelain to evoke natural forms.[79] These revivals emphasized fluid lines and matte greens derived from reduced iron content, departing from Minton's brighter tones to align with the style's emphasis on asymmetry and japonisme influences.[79] Productions at Sèvres and other centers produced limited-edition vases, marking celadon's transition from exotic import to modernist decorative art.[79]Americas

Celadon traditions entered the Americas in the 20th century through Asian immigration, particularly from China and Korea, who established pottery workshops in urban centers like San Francisco and Los Angeles.[80] Chinese immigrants, arriving post-1900 amid exclusionary laws, adapted celadon techniques in backyard kilns, producing green-glazed wares for ethnic communities and exporting to broader markets.[81] By the mid-century, Korean potters in California revived Goryeo-style celadons, firing stoneware with iron glazes to supply the growing Asian American diaspora.[82] In Mexico, talavera pottery features green glaze variants achieved with copper oxides for verdigris hues, with 20th-century potters in Puebla producing hand-painted tiles and vessels using tin-glaze methods fired at high temperatures for durability.[83] These adaptations, seen in architectural decoration, emerged via Pacific trade and migration routes, merging with colonial Spanish techniques.[84] Talavera's green iterations became staples in architectural decoration, reflecting enduring appeal in hybrid American contexts.[85]Contemporary Production and Collectibility

Contemporary celadon production thrives in key global centers, with South Korea's Icheon region standing out as a major hub due to its extensive kiln networks and the annual Icheon Ceramic Festival, which has been held since the late 1980s to showcase traditional and innovative celadon alongside other Korean ceramics.[86][87] This event, recognized as Korea's largest ceramics festival, draws international attention and supports ongoing production through workshops and exhibitions.[88] In Japan, the Mashiko area continues to produce celadon-inspired wares within its mingei folk pottery tradition, where artists experiment with celadon glazes on functional stoneware forms suited for everyday use.[89][90] In the United States, studio potters adapt celadon glazes for modern applications, creating pieces that blend Asian influences with contemporary aesthetics, as seen in works by artists like Gloria Cohen who incorporate celadon finishes on wheel-thrown vessels.[91] Technological and stylistic innovations have revitalized celadon production, including the widespread adoption of electric kilns that minimize wood consumption and emissions compared to traditional firing methods, making the process more accessible and environmentally friendly for small-scale studios.[92][93] Sustainable practices, such as sourcing wood ash from managed forestry byproducts, further address ecological concerns in glaze formulation.[92] Additionally, celadon aesthetics have merged with Western minimalism, evident in the subtle, unadorned porcelain works of artists like Edmund de Waal, who apply celadon glazes to evoke serenity and restraint in sculptural installations.[94] Celadon's collectibility remains strong, driven by the high market value of historical pieces; for example, a Goryeo dynasty inlaid celadon maebyong vase fetched $85,000 at auction, underscoring demand for rare antique examples.[95] To combat fakes, thermoluminescence dating is routinely employed, as it measures trapped electrons in the clay to determine the object's last firing date and verify authenticity.[96][97] Efforts to revive celadon culturally include UNESCO's recent project (2024–2025) to safeguard the living heritage of Koryo celadon in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, focusing on traditional making practices and kiln sites.[98] Contemporary artists like Park Young Sook contribute to this revival through her masterful porcelain moon jars glazed in celadon tones, which reinterpret Joseon-era forms with precise technical innovation.[99][100] Post-2020 market trends reflect growing interest in eco-friendly ceramics, with sustainable celadon gaining traction amid heightened consumer awareness of environmental impact, as evidenced by a surge in Etsy searches for "eco" related items.[101] Online platforms like Etsy and 1stDibs have boosted accessibility, enabling direct sales of handmade, low-impact celadon pieces to global collectors.[101][102]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ewer,_Ly-Tran_dynasty,_11th-14th_century_AD,_brown_and_celadon_glazed_ceramic_-_National_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History_-_Hanoi,_Vietnam_-_DSC05514.JPG