Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

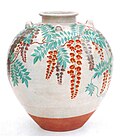

Suribachi

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Suribachi (擂鉢, lit. "grinding-bowl") and surikogi (擂粉木, lit. "grind-powder-wood") are a Japanese mortar and pestle. These mortars are used in Japanese cooking to crush different ingredients such as sesame seeds.[1]

Form

[edit]The suribachi is a pottery bowl, glazed on the outside and with a rough pattern called kushi-no-me on the unglazed inside. This surface is somewhat similar to the surface of the oroshigane (grater). The surikogi pestle is made from wood to avoid excessive wear on the suribachi. Traditionally, the wood from the sanshō tree (Japanese prickly ash) was used, which adds a slight flavor to the food, although nowadays other woods are more common. The bowls have a diameter from 10 to 30 centimeters (3.9 to 11.8 inches).

Use

[edit]To use the suribachi the bowl is set on a non-slip surface, such as a rubber mat or a damp towel, and the surikogi is used to grind the material. Recently, plastic versions of the suribachi have also become popular, but they have a much shorter life-span.

History

[edit]The suribachi and surikogi arrived in Japan from China around A.D. 1000. The mortar was first used for medicine, and only later for food products. A larger sized Japanese mortar used to pound rice is an usu with a pestle called kine.[2][3]

In culture

[edit]The highest mountain on Iwo Jima, Mount Suribachi, was named after this kitchen device.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Randal, Oulton (28 May 2005). "Suribachi". CooksInfo.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Suribachi - Japanese Mortar And Pestle". Gourmet Sleuth. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Itoh, Makiko (24 June 2017). "Getting in the groove with 'suribachi' and 'surikogi,' the Japanese mortar and pestle". The Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Japanese Mortar Bowl and Pestle". Good Gray. Archived from the original on 2024-03-20. Retrieved 2023-09-08.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Suribachi and surikogi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Suribachi and surikogi at Wikimedia Commons