Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

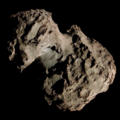

Coma (comet)

View on Wikipedia

The coma is the nebulous envelope around the nucleus of a comet, formed when the comet passes near the Sun in its highly elliptical orbit. As the comet warms, parts of it sublimate;[1] this gives a comet a diffuse appearance when viewed through telescopes and distinguishes it from stars. The word coma comes from the Greek κόμη (kómē), which means "hair" and is the origin of the word comet itself.[2][3]

The coma is generally made of ice and comet dust.[1] Water composes up to 90% of the volatiles that outflow from the nucleus when the comet is within 3–4 au (280–370 million mi; 450–600 million km) from the Sun.[1] The H2O parent molecule is destroyed primarily through photodissociation and to a much smaller extent photoionization.[1] The solar wind plays a minor role in the destruction of water compared to photochemistry.[1] Larger dust particles are left along the comet's orbital path while smaller particles are pushed away from the Sun into the comet's tail by light pressure.

On 11 August 2014, astronomers released studies, using the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) for the first time, that detailed the distribution of HCN, HNC, H2CO, and dust inside the comae of comets C/2012 F6 (Lemmon) and C/2012 S1 (ISON).[4][5] On 2 June 2015, NASA reported that the ALICE spectrograph on the Rosetta space probe studying comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko determined that electrons (within 1 km (0.62 mi) above the comet nucleus) produced from photoionization of water molecules by solar radiation, and not photons from the Sun as thought earlier, are responsible for the liberation of water and carbon dioxide molecules released from the comet nucleus into its coma.[6][7]

Size

[edit]

Comas typically grow in size as comets approach the Sun, and they can be as large as the diameter of Jupiter, even though the density is very low.[2] About a month after an outburst in October 2007, comet 17P/Holmes briefly had a tenuous dust atmosphere larger than the Sun.[8] The Great Comet of 1811 also had a coma roughly the diameter of the Sun.[9] Even though the coma can become quite large, its size can actually decrease about the time it crosses the orbit of Mars around 1.5 AU from the Sun.[9] At this distance the solar wind becomes strong enough to blow the gas and dust away from the coma, enlarging the tail.[9]

X-rays

[edit]

Comets were found to emit X-rays in late-March 1996.[10] This surprised researchers, because X-ray emission is usually associated with very high-temperature bodies. Thomas E. Cravens was the first to propose an explanation in early 1997.[11] The X-rays are thought to be generated by the interaction between comets and the solar wind: when highly charged ions fly through a cometary atmosphere, they collide with cometary atoms and molecules, "ripping off" one or more electrons from the comet. This ripping off leads to the emission of X-rays and far ultraviolet photons.[12]

Observation

[edit]With a basic Earth-surface based telescope and some technique, the size of the coma can be calculated.[13] Called the drift method, one locks the telescope in position and measures the time for the visible disc to pass through the field of view.[13] That time multiplied by the cosine of the comet's declination, times .25, should equal the coma's diameter in arcminutes.[13] If the distance to the comet is known, then the apparent size of the coma can be determined.[13]

In 2015, it was noted that the ALICE instrument on the ESA Rosetta spacecraft to comet 67/P, detected hydrogen, oxygen, carbon and nitrogen in the coma, which they also called the comet's atmosphere.[14] Alice is an ultraviolet spectrograph, and it found that electrons created by UV light were colliding and breaking up molecules of water and carbon monoxide.[14]

Hydrogen gas halo

[edit]

OAO-2 ('Stargazer') discovered large halos of hydrogen gas around comets.[15] Space probe Giotto detected hydrogen ions at distance of 7.8 million km away from Halley when it did a close flyby of the comet in 1986.[16] A hydrogen gas halo was detected to be 15 times the diameter of Sun (12.5 million miles). This triggered NASA to point the Pioneer Venus mission at the Comet, and it was determined that the Comet was emitting 12 tons of water per second. The hydrogen gas emission has not been detected from Earth's surface because those wavelengths are blocked by the atmosphere.[17] The process by which water is broken down into hydrogen and oxygen was studied by the ALICE instrument aboard the Rosetta spacecraft.[18] One of the issues is where the hydrogen is coming from and how (e.g. Water splitting):

First, an ultraviolet photon from the Sun hits a water molecule in the comet's coma and ionises it, knocking out an energetic electron. This electron then hits another water molecule in the coma, breaking it apart into two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen, and energising them in the process. These atoms then emit ultraviolet light that is detected at characteristic wavelengths by Alice.[18]

A hydrogen gas halo three times the size of the Sun was detected by Skylab around Comet Kohoutek in the 1970s.[19] SOHO detected a hydrogen gas halo bigger than 1 AU in radius around Comet Hale–Bopp.[20] Water emitted by the comet is broken up by sunlight, and the hydrogen in turn emits ultra-violet light.[21] The halos have been measured to be ten billion meters across, many times bigger than the Sun.[21] The hydrogen atom are very light so they can travel a long distance before they are themselves ionized by the Sun.[21] When the hydrogen atoms are ionized they are especially swept away by the solar wind.[21]

Composition

[edit]

The Rosetta mission found carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ammonia, methane and methanol in the Coma of Comet 67P, as well as small amounts of formaldehyde, hydrogen sulfide, hydrogen cyanide, sulfur dioxide and carbon disulfide.[22]

The four top gases in 67P's halo were water, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and oxygen.[23] The ratio of oxygen to water coming off the comet remained constant for several months.[23]

Coma spectrum

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Combi, Michael R.; Harris, W. M.; Smyth, W. H. (2004). "Gas Dynamics and Kinetics in the Cometary Coma: Theory and Observations" (PDF). Comets II. 745. Lunar and Planetary Institute: 523–552. Bibcode:2004come.book..523C. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ^ a b "Chapter 14, Section 2 | Comet appearance and structure". lifeng.lamost.org. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ "comet". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ^ Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Neal-Jones, Nancy (11 August 2014). "RELEASE 14-038 - NASA's 3-D Study of Comets Reveals Chemical Factory at Work". NASA. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ Cordiner, M.A.; et al. (11 August 2014). "Mapping the Release of Volatiles in the Inner Comae of Comets C/2012 F6 (Lemmon) and C/2012 S1 (ISON) Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array". The Astrophysical Journal. 792 (1): L2. arXiv:1408.2458. Bibcode:2014ApJ...792L...2C. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/792/1/L2. S2CID 26277035.

- ^ Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne; Fohn, Joe; Bauer, Markus (2 June 2015). "NASA Instrument on Rosetta Makes Comet Atmosphere Discovery". NASA. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ Feldman, Paul D.; A'Hearn, Michael F.; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Feaga, Lori M.; Parker, Joel Wm.; et al. (2 June 2015). "Measurements of the near-nucleus coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko with the Alice far-ultraviolet spectrograph on Rosetta" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 583: A8. arXiv:1506.01203. Bibcode:2015A&A...583A...8F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525925. S2CID 119104807.

- ^ Jewitt, David (2007-11-09). "Comet Holmes Bigger Than The Sun". Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ a b c Gary W. Kronk. "The Comet Primer". Cometography.com. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ "First X-Rays from a Comet Discovered". Goddard Spaceflight Center. Archived from the original on 2012-07-25. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ Cravens, T. E. (1997). "Comet Hyakutake x-ray source: Charge transfer of solar wind heavy ions". Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (1).

- ^ "Interaction model – Probing space weather with comets". KVI atomics physics. Archived from the original on 2006-02-13. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ a b c d Levy, D.H. (2003). David Levy's Guide to Observing and Discovering Comets. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780521520515. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ a b "Ultraviolet study reveals surprises in comet coma / Rosetta / Space Science / Our Activities / ESA". esa.int. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ "Orbiting Astronomical Observatory OAO-2". sal.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ "Giotto overview / Space Science / Our Activities / ESA". esa.int. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ "About Comets". lpi.usra.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ a b "Ultraviolet study reveals surprises in comet coma | Rosetta – ESA's comet chaser". blogs.esa.int. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ Lundquist, C. A. (January 1979). "SP-404 Skylab's Astronomy and Space Sciences Chapter 4 Observations of Comet Kohoutek". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ Burnham, R. (2000). Great Comets. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780521646000. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ a b c d "NASA's Cosmos". ase.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ "The scent of a comet: Rotten eggs and pee – CNET". cnet.com. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ a b "Rosetta finds molecular oxygen on comet 67P (Update)". phys.org. Retrieved 2017-01-08.