Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Swan Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mute swan (Cygnus olor) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Subfamily: | Anserinae |

| Genus: | Cygnus Garsault, 1764 |

| Type species | |

| Anas olor[3] (now Cygnus olor) Gmelin, 1789

| |

| Species | |

|

6 living, see text. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cygnanser Kretzoi, 1957 | |

Swans are birds of the genus Cygnus within the family Anatidae. The swans' closest relatives include geese and ducks. Swans are grouped with the closely related geese in the subfamily Anserinae, forming the tribe Cygnini. Sometimes, they are considered a distinct subfamily, Cygninae. They are the largest waterfowl and are often among the largest flighted birds in their range.

There are six living and many extinct species of swan; in addition, there is a species known as the coscoroba swan, which is no longer considered one of the true swans. Swans usually mate for life, although separation sometimes occurs, particularly following nesting failure, and if a mate dies, the remaining swan will take up with another. The number of eggs in each clutch ranges from three to eight.[4]

Taxonomy and terminology

[edit]The genus Cygnus was introduced in 1764 by the French naturalist François Alexandre Pierre de Garsault.[5][6] The English word swan, akin to the German Schwan, Dutch zwaan, and Swedish svan, is derived from the Indo-European root *swen(H) ('to sound, to sing').[7][8]

Young swans are known as cygnets, from Old French cigne or cisne (diminutive suffix et 'little'), from the Latin word cygnus, a variant form of cycnus 'swan', itself from the Greek κύκνος kýknos, a word of the same meaning.[9][10][11] An adult male is a cob, from Middle English cobbe (leader of a group); an adult female is a pen.[12] A group of swans is called a bevy[citation needed] or a wedge.[13]

Description

[edit]

Swans are the largest extant members of the waterfowl family Anatidae and are among the largest flying birds.[14] The largest living species, including the mute swan, trumpeter swan, and whooper swan, can reach a length of over 1.5 m (59 in) and weigh over 15 kg (33 lb). Their wingspans can be over 3.1 m (10 ft).[15] Compared to the closely related geese, they are much larger and have proportionally larger feet and necks.[16] Adults also have a patch of unfeathered skin between the eyes and bill. The sexes are alike in plumage, but males are generally bigger and heavier than females.[12] The biggest species of swan ever was the extinct Cygnus falconeri, a flightless giant swan known from fossils found on the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Sicily; its disappearance is thought to have resulted from extreme climate fluctuations or the arrival of superior predators and competitors.[17]

The Northern Hemisphere species of swan have pure white plumage, while the Southern Hemisphere species are mixed black and white. The Australian black swan (Cygnus atratus) is completely black except for the white flight feathers on its wings; the chicks of black swans are light grey. The South American black-necked swan has a white body with a black neck.[18]

The legs of most swans are typically a dark blackish-grey colour, except for the South American black-necked swan, which has pink legs. Bill colour varies: the four subarctic species have black bills with varying amounts of yellow, and all the others are patterned red and black. Although birds do not have teeth, swans, like other Anatidae, have beaks with serrated edges that look like small jagged "teeth" as part of their beaks, which are used for catching and eating aquatic plants and algae, as well as molluscs, small fish, frogs, and worms.[19] In the mute swan and black-necked swan, both sexes have a fleshy lump at the base of their bills on the upper mandible, known as the knob, which is larger in males and is condition-dependent, changing seasonally.[20][21]

Distribution and movements

[edit]

Swans are generally found in temperate environments, rarely occurring in the tropics. Four (or five) species occur in the Northern Hemisphere, one species is found in Australia, one extinct species was found in New Zealand and the Chatham Islands, and one species is distributed in southern South America. They are absent from tropical Asia, Central America, northern South America and the entirety of Africa. One species, the mute swan, has been introduced to North America, Australia and New Zealand.[16]

Several species are migratory, either wholly or partly so. The mute swan is a partial migrant, being resident over areas of Western Europe but wholly migratory in Eastern Europe and Asia. The tundra swan is wholly migratory, and the whooper swan and trumpeter swan are almost entirely migratory.[16] There is some evidence that the black-necked swan is migratory over part of its range, but detailed studies have not established whether these movements constitute long- or short-range migration.[22]

Behaviour

[edit]

Swans feed in water and on land. They are almost entirely herbivorous, although they may eat small amounts of aquatic animals. In the water, food is obtained by up-ending or dabbling, and their diet is composed of the roots, tubers, stems, and leaves of aquatic and submerged plants.[16]

A familiar behaviour of swans is that they mate for life and typically bond even before they reach sexual maturity. Trumpeter swans, for example, can live as long as 24 years and only start breeding at the age of 4–7, forming monogamous pair bonds as early as 20 months.[23] "Divorce", though rare, does occur; one study of mute swans shows a 3% rate for pairs that breed successfully and 9% for pairs that do not.[24] The pair bonds are maintained year-round, even in gregarious and migratory species like the tundra swan, which congregate in large flocks in the wintering grounds.[25]

Swans' nests are on the ground near water and about a metre (3') across. Unlike many other ducks and geese, the male helps with the nest construction and will also take turns incubating the eggs.[26] Alongside the whistling ducks, swans are the only anatids that will do this. The average egg size (for the mute swan) is 113 × 74 mm (4+1⁄2 x 3 in), weighing 340 g (12 oz), in a clutch size of 4 to 7, with an incubation period of 34–45 days.[27] Swans are highly protective of their nests. They will viciously attack anything that they perceive as a threat to their chicks, including humans; one man was suspected to have drowned in such an attack.[28][29] Swans' intraspecific aggressive behaviour is shown more frequent than interspecific behaviour for food and shelter. The aggression with other species is shown more in tundra swans.[30]

Systematics and evolution

[edit]

Evidence suggests that the genus Cygnus evolved in Europe or western Eurasia during the Miocene, spreading all over the Northern Hemisphere until the Pliocene. When the southern species branched off is not known. The mute swan is closest to the Southern Hemisphere Cygnus;[31] its habits of carrying the neck curved (not straight) and the wings fluffed (not flush) as well as its bill colour and knob indicate that its closest living relative is the black swan. Given the biogeography and appearance of the subgenus Olor, it seems likely that these are of a more recent origin, as evidenced shows by their modern ranges (which were mostly uninhabitable during the last ice age) and great similarity between the taxa.[1]

Phylogeny

[edit]| Cygnus |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species

[edit]Genus Cygnus

| Subgenus | Image | Scientific name | Common name | Description | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus Cygnus |

|

Cygnus olor | Mute swan | Eurasian species that occurs across Europe into southern Russia, China, and the Russian Maritime Territory, at lower latitudes compared to the whooper swan and Bewick's swan. According to the British Ornithologists' Union, recent fossil records show that Cygnus olor is among the oldest bird species still extant; it has been upgraded to "native" status in several European countries since this bird has been found in fossil and bog specimens dating back thousands of years. While being common temperate Eurasian birds, often derived from semi-domesticated flocks, they are now naturalised in the United States and elsewhere. | Europe into southern Russia, China, and the Russian Maritime Territory; introduced populations in North America, Japan, Australasia, and southern Africa. |

| Subgenus Chenopis |

|

Cygnus atratus | Black swan | Nomadic with erratic migration patterns dependent upon climatic conditions. Black plumage and a red bill. | Australia, introduced into New Zealand and the Chatham Islands, with additional smaller introductions in Europe, the United States, Japan and China. |

| Subgenus Sthenelides |

|

Cygnus melancoryphus | Black-necked swan | South America | |

| Subgenus Olor |

|

Cygnus cygnus | Whooper swan | Breeds in Iceland and subarctic Europe and Asia, migrating to temperate Europe and Asia in winter | |

|

Cygnus buccinator | Trumpeter swan | The largest North American swan. Very similar to the whooper swan (and sometimes treated as a subspecies of it). It was hunted almost to extinction but has since recovered. | North America | |

|

Cygnus columbianus | Tundra swan | Breeds on the Arctic tundra and winters in more temperate regions of Eurasia and North America. It consists of two forms, generally regarded as subspecies, although some authorities treat them as separate species.[33]

|

North America, Eurasia |

The coscoroba swan (Coscoroba coscoroba) from South America, the only species in its genus, is not a true swan. Its phylogenetic position is not fully resolved; it is in some aspects more similar to geese and shelducks.[34]

Fossil record

[edit]The fossil record of the genus Cygnus is quite impressive, although allocation to the subgenera is often tentative; as indicated above, at least the early forms probably belong to the C. olor – Southern Hemisphere lineage, whereas the Pleistocene taxa from North America would be placed in Olor. Several prehistoric species have been described, mostly from the Northern Hemisphere. In the Mediterranean, the leg bones of the giant swan (C. falconeri) were found on the islands of Malta and Sicily; it may have been over 2 metres from tail to bill, which was taller (though not heavier) than the contemporary local dwarf elephants (Palaeoloxodon falconeri).

- Subgenus Chenopis

- †New Zealand swan, Cygnus sumnerensis, an extinct species related to the black swan of Australia

- Other subgenera (see above):

- †Cygnus atavus (Fraas 1870) Mlíkovský 1992 [Anas atava Fraas 1870; Anas cygniformis Fraas 1870; Palaelodus steinheimensis Fraas 1870; Anser atavus (Fraas 1870) Lambrecht 1933; Anser cygniformis (Fraas 1870) Lambrecht 1933] (Middle Miocene of Germany)

- †Cygnus csakvarensis Lambrecht 1933 [Cygnus csákvárensis Lambrecht 1931a nomen nudum; Cygnanser csakvarensis (Lambrecht 1933) Kretzoi 1957; Olor csakvarensis (Lambrecht 1933) Mlíkovský 1992b] (Late Miocene of Hungary)

- †Dwarf swan (Cygnus equitum) Bate 1916 sensu Livezey 1997 [Anser equitum (Bate 1916) Brodkorb 1964; Cygnus (Olor) equitum Bate 1916 sensu Northcote 1988a] (Middle – Late Pleistocene of Malta and Sicily, Mediterranean)

- †Giant swan (Cygnus falconeri) Parker 1865 sensu Livezey 1997a [Cygnus melitensis Falconer 1868; Palaeocygnus falconeri (Parker 1865) Oberholser 1908] (Middle Pleistocene of Malta and Sicily, Mediterranean)

- †Cygnus hibbardi Brodkorb 1958 (?Early Pleistocene of Idaho, U.S.)

- †Cygnus lacustris (De Vis 1905) [Archaeocycnus lacustris De Vis 1905] (Late Pleistocene of the Lake Eyre region, Australia)

- †Cygnus liskunae (Kuročkin 1976) [Anser liskunae Kuročkin 1976] (Middle Pliocene of western Mongolia)

- †Cygnus mariae Bickart 1990 (Late Miocene of Florida and Early Pliocene of Arizona, USA)[35][36]

- †Cygnus paloregonus Cope 1878 [Anser condoni Schufeldt 1892; Cygnus matthewi Schufeldt 1913] (Middle Pleistocene of west-central U.S.)

- †Cygnus verae Boev 2000 (Early Pliocene of Bulgaria)[37]

- †Cygnus sp. Louchart et al. 1998 (Early Pleistocene of Turkey)[38]

- †Cygnus sp. (Pleistocene of Australia)[39][40]

- Other genera

The supposed fossil swans "Cygnus" bilinicus and "Cygnus" herrenthalsi were, respectively, a stork and some large bird of unknown affinity (due to the bad state of preservation of the referred material).[41]

In culture

[edit]European motifs

[edit]Many of the cultural aspects refer to the mute swan of Europe. Perhaps the best-known story about a swan is the fairy tale "The Ugly Duckling". Swans are frequently regarded as symbols of love or fidelity, owing to their enduring and seemingly monogamous pair bonds. Swans feature prominently in two Wagner operas, Lohengrin and Parsifal.[42][43]

As food

[edit]Swan meat was regarded as a luxury food in England during the reign of Elizabeth I. A recipe for baked swan survives from that time: "To bake a Swan[,] scald it and take out the bones, and parboil it, then season it very well with Pepper, Salt and Ginger, then lard it, and put it in a deep Coffin of Rye Paste with store of Butter, close it and bake it very well, and when it is baked, fill up the Vent-hole with melted Butter, and so keep it; serve it in as you do the Beef-Pie."[44] Swans being raised for food were sometimes kept in swan pits.

The Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a religious confraternity that existed in 's-Hertogenbosch in the late Middle Ages, had "sworn members", also called "swan-brethren" because they used to donate a swan for the yearly banquet.

A common misconception holds that the British monarch owns all the swans in the United Kingdom and is uniquely permitted to eat them.[45][46]

Heraldry

[edit]-

A swan depicted on an Irish commemorative coin in celebration of its EU Council presidency

-

Coat of arms of writer Henryk Sienkiewicz's family, a variant of the Polish–Lithuanian coat of arms "Łabędź" (Polish for "Swan")

-

The flag of the Swiss municipality of Horgen; the swan symbolizes the town's location along the south bank of the Lake Zurich and its political status as the administrative capital of the Horgen District.

-

Coat of arms of the now-abolished Buckinghamshire County Council; a similar design is featured in the historic county's flag.

-

Coat of arms of Western Australia, with a black swan.

Ancient Greece and Rome

[edit]Swans feature strongly in mythology. In Greek mythology, the story of Leda and the Swan recounts that Helen of Troy was conceived in a union of Zeus disguised as a swan and Leda, Queen of Sparta.[47] Four different men (Cycnus, Cycnus, Cycnus, and Cycnus) are said to have been transformed into swans by the gods.

Other references in classical literature include the belief that, upon death, the mute swan would sing beautifully — hence the phrase "swan song".[48]

The mute swan is one of Apollo's sacred birds, associated both with light and with the concept of a "swan song". Apollo is often shown riding a chariot pulled by, or made of, swans during his ascension from Delos.

In the second century, the Roman poet Juvenal made a sarcastic reference to a good woman being a "rare bird, as rare on earth as a black swan" (black swans being completely unknown in the Northern Hemisphere until Dutch explorers reached Australia in the 1600s), from which comes the Latin phrase rara avis ("rare bird").[49]

Irish lore and poetry

[edit]The Irish legend of the Children of Lir is about a stepmother who transformed her children into swans for 900 years.[50]

In the legend The Wooing of Etain, the king of the Sidhe (subterranean-dwelling, supernatural beings) transforms himself and the most beautiful woman in Ireland, Etain, into swans to escape from the king of Ireland and Ireland's armies. The swan has recently been depicted on an Irish commemorative coin.

Swans are also present in Irish literature in the poetry of W. B. Yeats; "The Wild Swans at Coole" has a heavy focus on the mesmerising characteristics of the swan. Yeats also recounts the myth of Leda and the Swan in the poem of the same name.

Nordic lore

[edit]In Norse mythology, two swans drink from the sacred Well of Urd in the realm of Asgard, home of the gods. According to the Prose Edda, the water of this well is so pure and holy that all things that touch it turn white, including this original pair of swans and all others descended from them. The poem Volundarkvida, or the Lay of Volund, part of the Poetic Edda, also features swan maidens.

In the Finnish epic Kalevala, a swan lives in the Tuoni River located in Tuonela, the underworld realm of the dead; according to the story, whoever killed a swan would perish as well. Jean Sibelius composed the Lemminkäinen Suite based on the Kalevala, with the second piece entitled Swan of Tuonela (Tuonelan joutsen). Today, five flying swans are the symbol of the Nordic countries; the whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) is the national bird of Finland,[51] and the mute swan is the national bird of Denmark.[52]

Swan Lake ballet

[edit]The ballet Swan Lake is one of the most canonical classical ballets. Based on the 1875–76 score by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the most promulgated choreographic version was created by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov (1895), the premiere of which was danced by the Imperial Ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. The ballet's lead dual roles of Odette (white swan)/Odile (black swan) represent good and evil,[53] and they are among the most challenging roles created in Romantic classical ballet. The ballet is included in the repertories of ballet companies worldwide.[54]

Christianity

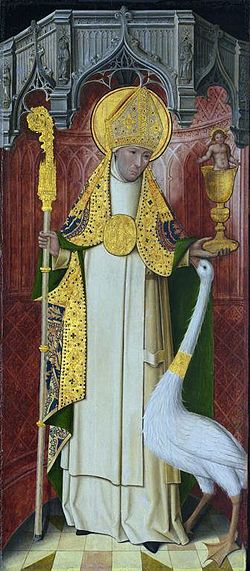

[edit]

A swan is one of the attributes of St. Hugh of Lincoln, based on the story of a swan that was devoted to him.[55]

Spanish language literature

[edit]In Latin American literature, the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío (1867–1916) consecrated the swan as a symbol of artistic inspiration by drawing attention to the constancy of swan imagery in Western culture, beginning with the rape of Leda and ending with Wagner's Lohengrin. Darío's most famous poem in this regard is Blasón – "Coat of Arms" (1896), and his use of the swan made it a symbol for the Modernismo poetic movement that dominated Spanish language poetry from the 1880s until the First World War. Such was the dominance of Modernismo in Spanish language poetry that the Mexican poet Enrique González Martínez attempted to announce the end of Modernismo with a sonnet provocatively entitled Tuércele el cuello al cisne – "Wring the Swan's Neck" (1910).

Hinduism

[edit]In Hinduism, swans are revered and likened to saintly persons who live in the world without attachment, much like a swan's feather stays dry in water. The Sanskrit word for swan is hamsa and the "Raja Hamsam" or the Royal Swan is the vehicle of the Devi Saraswati, which symbolises the Sattva Guna ("purity par excellence"). The swan, if offered a mixture of milk and water, is said to be able to drink the milk alone. Therefore, Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, is seen riding the swan because the swan thus symbolizes Viveka, i.e. prudence and discrimination between the good and the bad or between the eternal and the transient; this is seen as a great quality, as shown by this Sanskrit verse:

|

|

As mentioned several times in the Vedic literature, persons who have attained great spiritual capabilities are sometimes called Paramahamsa ("Supreme Swan") on account of their spiritual grace and ability to travel between various spiritual worlds. In the Vedas, swans are said to reside on Lake Manasarovar during the summer and to migrate to Indian lakes for the winter; they are also believed to possess some powers, such as the ability to eat pearls.

Indo-European religions

[edit]Swans are intimately associated with the divine twins in Indo-European religions, and it is thought that in Proto-Indo-European times, swans were a solar symbol associated with the divine twins and the original Indo-European sun goddess.[56]

See also

[edit]- Swan upping (an annual ceremony happening since the 16th century, in which mute swans on the River Thames are rounded up, caught, ringed, and released, on behalf of the British Crown, the Worshipful Company of Vintners and the Worshipful Company of Dyers, each of which is entitled to one-third of the Thames swans).

- Royal Swans (swans given by Queen Elizabeth II to the city of Ottawa in 1967, and their progeny)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Northcote, E. M. (1981). "Size difference between limb bones of recent and subfossil Mute Swans (Cygnus olor)". J. Archaeol. Sci. 8 (1): 89–98. Bibcode:1981JArSc...8...89N. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(81)90014-5.

- ^ "Fossilworks Cygnus Garsault 1764 (waterfowl) Reptilia – Anseriformes – Anatidae PaleoDB taxon number: 83418 Parent taxon: Anatidae according to T. H. Worthy and J. A. Grant-Mackie 2003 See also Bickart 1990, Howard 1972, Parmalee 1992 and Wetmore 1933". Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ "Anatidae". aviansystematics.org. The Trust for Avian Systematics. Retrieved 2023-08-05.

- ^ "Swan Breeding Profile: Pairing, Incubation, Nesting / Raising of Young". Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Garsault, François Alexandre Pierre de (1764). Les figures des plantes et animaux d'usage en medecine, décrits dans la Matiere Medicale de Geoffroy Medecin (in French). Vol. 5. Paris: Desprez. Plate 688.

- ^ Welter-Schultes, F.W.; Klug, R. (2009). "Nomenclatural consequences resulting from the rediscovery of Les figures des plantes et animaux d'usage en médecine, a rare work published by Garsault in 1764, in the zoological literature". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 66 (3): 225–241 [238]. doi:10.21805/bzn.v66i3.a1.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "swan". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-19-928791-0.

- ^ cycnus. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ κύκνος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "cygnet". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Young, Peter (2008). Swan. London: Reaktion. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-86189-349-9.

- ^ Lipton, James (1977). An Exaltation of Larks: Or, The Venereal Game. Internet Archive (Expanded 2nd ed.). New York : Viking. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-670-30044-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ "ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA Swan". Archived from the original on 2018-05-21. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1988). Waterfowl: An Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-46727-5.

- ^ a b c d Kear, Janet, ed. (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans. Bird Families of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861008-3.

- ^ "Mindat.org". www.mindat.org. Archived from the original on 2021-11-27. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Young, Peter (2008). Swan. London: Reaktion. pp. 18–27. ISBN 978-1-86189-349-9.

- ^ "Mute Swan. Feeding" Archived 25 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

- ^ Young, Peter (2008). Swan. London: Reaktion. pp. 20 and 27. ISBN 978-1-86189-349-9.

- ^ Horrocks, N., Perrins, C. and Charmantier, A., 2009. Seasonal changes in male and female bill knob size in the mute swan Cygnus olor. Journal of avian biology, 40(5), pp.511-519.

- ^ Schlatter, Roberto; Navarro, Rene A.; Corti, Paulo (2002). "Effects of El Nino Southern Oscillation on Numbers of Black-Necked Swans at Rio Cruces Sanctuary, Chile". Waterbirds. 25 (Special Publication 1): 114–122. JSTOR 1522341.

- ^ Ross, Drew (March–April 1998). "Gaining Ground: A Swan's Song". National Parks. 72 (3–4): 35. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

- ^ Berger, Michele (11 June 2018). "Till Death do them Part: 8 Birds that Mate for Life". National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018 – via www.audubon.org.

- ^ Scott, D. K. (1980). "Functional aspects of the pair bond in winter in Bewick's swans (Cygnus columbianus bewickii)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 7 (4): 323–327. Bibcode:1980BEcoS...7..323S. doi:10.1007/BF00300673. S2CID 32804332.

- ^ Scott, Dafila (1995). Swans. Grantown-on-Spey, Scotland: Colin Baxter Photography. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-948661-63-1.

- ^ "Mute Swan" Archived 2012-07-08 at archive.today. British Trust for Ornithology

- ^ Waldren, Ben (16 April 2012). "Killer Swan Blamed for Man's Drowning". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Who, What, Why: How dangerous are swans?". BBC News. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012.

- ^ Wood, Kevin A.; Ham, Phoebe; Scales, Jake; Wyeth, Eleanor; Rose, Paul E. (7 August 2020). "Aggressive behavioural interactions between swans (Cygnus spp.) and other waterbirds during winter: a webcam-based study". Avian Research. 11 (1): 30. doi:10.1186/s40657-020-00216-7. hdl:10871/126306. ISSN 2053-7166.

- ^ del Hoyo; et al., eds. (1992). Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 1. Lynx Edicions.

- ^ Boyd, John H. "Anserini species tree" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Overzicht van alle vogels waargenomen in Nederland". Dutch Avifauna (in Dutch). Retrieved 2025-05-17.

- ^ "COSCOROBA SWAN". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016.

- ^ Bickart, K.J. (1990). "Part I: The birds of the late Miocene-early Pliocene Big Sandy Formation, Mohave County, Arizona". Ornithological Monographs. 44 (1): 1–72. doi:10.2307/40166673. JSTOR 40166673.

- ^ Steadman, David; Takano, Oona (April 2019). "A new genus and species of heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the late Miocene of Florida". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 55 (9): 174–186. doi:10.58782/flmnh.qskt9951. ISSN 2373-9991.

- ^ Boev, Z. 2000. "Cygnus verae sp. n. (Anseriformes: Anatidae) from the Early Pliocene of Sofia (Bulgaria)". Acta zoologica cracovienzia, Krakow, 43 (1–2): 185–192.

- ^ Louchart, Antoine; Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile; Guleç, Erksin; Howell, Francis Clark; White, Tim D. (1998). "L'Avifaune de Dursunlu, Turquie, Pléistocène inférieur: Climat, environnement et biogéographie" [The avifauna of Dursunlu, Turkey, Lower Pleistocene: climate, environment and biogeography]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences - Series IIA - Earth and Planetary Science. 327 (5): 341–346. Bibcode:1998CRASE.327..341L. doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(98)80053-0.

- ^ Louchart, Antoine; Vignaud, Patrick; Likius, Andossa; Mackaye, Hassane T.; Brunet, Michel (27 June 2005). "A New Swan (Aves: Anatidae) in Africa, from the Latest Miocene of Chad and Libya". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 384–392. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0384:ANSAAI]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524452. S2CID 85860957.

- ^ Sfetcu, Nicolae (2011). The Birds World. ISBN 9781447875857.

- ^ Mlíkovský, Jiří (2002). Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe (PDF). Vol. 121. Prague: Ninox Press. p. 123. doi:10.1093/auk/121.2.623. ISBN 80-901105-3-8

{{isbn}}: ignored ISBN errors (link). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2016.{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Rahim, Sameer (4 June 2013). "The opera novice: Wagner's Lohengrin". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Rahim, Sameer (5 March 2013). "The opera novice: Parsifal by Richard Wagner". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Baked Swan. Old Elizabethan Recipe". elizabethan-era.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010.

- ^ Cleaver, Emily (July 31, 2017). "The Fascinating, Regal History Behind Britain's Swans". Smithsonian. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Little girl asks to borrow swan, Queen responds". The New Zealand Herald. September 2, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Young, Peter (2008). Swan. London: Reaktion. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-86189-349-9.

- ^ "What is the origin of the phrase 'Swan song'?". phrases.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Young, Peter (2008). Swan. London: Reaktion. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-86189-349-9.

- ^ "The Fate of the Children of Lir". ancienttexts.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Whooper Swan". wwf.panda.org. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "BIRDS OF DENMARK". birdlist.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ MacAulay, Alastair (12 June 2018). "All About Odette, Tchaikovsky's Swan Queen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Inside Swan Lake: Why the Classic Ballet is Truly Timeless". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2019-07-31. Retrieved 2019-07-31.

- ^ Young, Peter (2008). Swan. London: Reaktion. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-86189-349-9.

- ^ O'Brien, Steven (1982). "Dioscuric Elements in Celtic and Germanic Mythology". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 10 (1 & 2): 117–136.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Louchart, Antoine; Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile; Guleç, Erksin; Howell, Francis Clark & White, Tim D. (1998): L'avifaune de Dursunlu, Turquie, Pléistocène inférieur: climat, environnement et biogéographie. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris IIA 327(5): 341–346. [French with English abridged version] doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(98)80053-0

- A History of British Birds

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . . 1914.