Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Comic opera

View on Wikipedia

Comic opera, sometimes known as light opera, is a sung dramatic work of a light or comic nature, usually with a happy ending and often including spoken dialogue.

Forms of comic opera first developed in late 17th-century Italy. By the 1730s, a new operatic genre, opera buffa, emerged as an alternative to opera seria. It quickly made its way to France, where it became opéra comique, and eventually, in the following century, French operetta, with Jacques Offenbach as its most accomplished practitioner.

The influence of Italian and French forms spread to other parts of Europe. Many countries developed their own genres of comic opera, incorporating the Italian and French models along with their own musical traditions. Examples include German singspiel, Viennese operetta, Spanish zarzuela, Russian comic opera, English ballad and Savoy opera, North American operetta and musical comedy.

Italian opera buffa

[edit]

In late 17th-century Italy, light-hearted musical plays began to be offered as an alternative to weightier opera seria (17th-century Italian opera based on classical mythology). Il Trespolo tutore (1679) by Alessandro Stradella was an early precursor of opera buffa. The opera has a farcical plot, and the characters of the ridiculous guardian Trespolo and the maid Despina are prototypes of characters widely used later in the opera buffa genre.

The form began to flourish in Naples with Alessandro Scarlatti's Il trionfo dell'onore (1718). At first written in Neapolitan dialect, these works became "Italianized" with the operas of Scarlatti, Pergolesi (La serva padrona, 1733), Galuppi (Il filosofo di campagna, 1754), Piccinni (La Cecchina, 1760), Paisiello (Nina, 1789), Cimarosa (Il matrimonio segreto, 1792), and then the great comic operas of Mozart and, later, Rossini and Donizetti.

At first, comic operas were generally presented as intermezzi between acts of more serious works. Neapolitan and then Italian comic opera grew into an independent form and became the most popular form of staged entertainment in Italy from about 1750 to 1800. In 1749, thirteen years after Pergolesi's death, his La serva padrona swept Italy and France, evoking the praise of such French Enlightenment figures as Rousseau.

In 1760, Niccolò Piccinni wrote the music to La Cecchina to a text by the great Venetian playwright, Carlo Goldoni. That text was based on Samuel Richardson's popular English novel, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740). Many years later, Verdi called La Cecchina the "first true Italian comic opera" – that is to say, it had everything: it was in standard Italian and not in dialect; it was no longer simply an intermezzo, but rather an independent piece; it had a real story that people liked; it had dramatic variety; and, musically, it had strong melodies and even strong supporting orchestral parts, including a strong "stand-alone" overture (i.e., you could even enjoy the overture as an independent orchestral piece). Verdi was also enthusiastic because the music was by a southern Italian and the text by a northerner, which appealed to Verdi's pan-Italian vision.

The genre was developed further in the first half of the 19th century by Gioachino Rossini in his works such as The Barber of Seville (1816) and La Cenerentola (1817) and by Gaetano Donizetti in L'elisir d'amore (1832) and Don Pasquale (1843), but declined in the mid-19th century, despite Giuseppe Verdi's Falstaff staged in 1893.

French opéra comique and operetta

[edit]

French composers eagerly seized upon the Italian model and made it their own, calling it opéra comique. Early proponents included the Italian Egidio Duni, François-André Philidor, Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny, André Grétry, François-Adrien Boïeldieu, Daniel François Auber and Adolphe Adam. Although originally reserved for less serious works, the term opéra comique came to refer to any opera that included spoken dialogue, including works such as Cherubini's Médée and Bizet's Carmen that are not "comic" in any sense of the word.

Florimond Hervé is credited as the inventor of French opéra bouffe, or opérette.[1] Working on the same model, Jacques Offenbach quickly surpassed him, writing over ninety operettas. Whereas earlier French comic operas had a mixture of sentiment and humour, Offenbach's works were intended solely to amuse. Though generally well crafted and full of humorous satire and grand opera parodies, plots and characters in his works were often interchangeable. Given the frenetic pace at which he worked, Offenbach sometimes used the same material in more than one opera. Another Frenchman who took up this form was Charles Lecocq.

German singspiel and Viennese operetta

[edit]The singspiel developed in 18th-century Vienna and spread throughout Austria and Germany. As in the French opéra comique, the singspiel was an opera with spoken dialogue, and usually a comic subject, such as Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782) and The Magic Flute (1791). Later singspiels, such as Beethoven's Fidelio (1805) and Weber's Der Freischütz (1821), retained the form, but explored more serious subjects.

19th century Viennese operetta was built on both the singspiel and the French model. Franz von Suppé is remembered mainly for his overtures. Johann Strauss II, the "waltz king", contributed Die Fledermaus (1874) and The Gypsy Baron (1885). Carl Millöcker a long-time conductor at the Theater an der Wien, also composed some of the most popular Viennese operettas of the late 19th century, including Der Bettelstudent (1882), Gasparone (1884) and Der arme Jonathan (1890).

After the turn of the 20th century, Franz Lehár wrote The Merry Widow (1905); Oscar Straus supplied Ein Walzertraum ("A Waltz Dream", 1907) and The Chocolate Soldier (1908); and Emmerich Kálmán composed Die Csárdásfürstin (1915).

Spanish zarzuela

[edit]Zarzuela, introduced in Spain in the 17th century, is rooted in popular Spanish traditional musical theatre. It alternates between spoken and sung scenes, the latter incorporating dances, with chorus numbers and humorous scenes that are usually duets. These works are relatively short, and ticket prices were often low, to appeal to the general public. There are two main forms of zarzuela: Baroque zarzuela (c. 1630–1750), the earliest style, and Romantic zarzuela (c. 1850–1950), which can be further divided into the two subgenres of género grande and género chico.

Pedro Calderón de la Barca was the first playwright to adopt the term zarzuela for his work entitled El golfo de las sirenas ("The Gulf of the Sirens", 1657). Lope de Vega soon wrote a work titled La selva sin amor, drama con orquesta ("The Loveless Jungle, A Drama with Orchestra"). The instruments orchestra was hidden from the audience, the actors sang in harmony, and the musical composition itself was intended to evoke an emotional response. Some of these early pieces were lost, but Los celos hacen estrellas ("Jealousies Turn Into Stars") by Juan Hidalgo and Juan Vélez, which premiered in 1672, survives and gives us some sense of what the genre was like in the 17th century.

In the 18th century, the Italian operatic style influenced zarzuela. But beginning with the reign of Bourbon King Charles III, anti-Italian sentiment increased. Zarzuela returned to its roots in popular Spanish tradition in works such as the sainetes (or Entr'actes) of Don Ramón de la Cruz. This author's first work in this genre was Las segadoras de Vallecas ("The Reapers of Vallecas", 1768), with music by Rodríguez de Hita.

Single act zarzuelas were classified as género chico (the "little genre" or "little form") and zarzuelas of three or more acts were género grande (the "big genre" or "big form"). Zarzuela grande battled on at the Teatro de la Zarzuela de Madrid, but with little success and light attendance. In spite of this, in 1873 a new theater, the Teatro Apolo, was opened for zarzuela grande, which shared the failures of the Teatro de la Zarzuela, until it was forced to change its program to género chico.

Russian comic opera

[edit]The first opera presented in Russia, in 1731, was a comic opera (or "commedia per musica"), Calandro, by an Italian composer, Giovanni Alberto Ristori. It was followed by the comic operas of other Italians, like Galuppi, Paisiello and Cimarosa, and also Belgian/French composer Grétry.

The first Russian comic opera was Anyuta (1772). The text was written by Mikhail Popov, with music by an unknown composer, consisting of a selection of popular songs specified in the libretto. Another successful comic opera, The miller who was a wizard, a cheat and a matchmaker, text by Alexander Ablesimov (1779), on a subject resembling Rousseau's Devin, is attributed to Mikhail Sokolovsky. Ivan Kerzelli, Vasily Pashkevich and Yevstigney Fomin also wrote a series of successful comic operas in the 18th century.

In the 19th century, Russian comic opera was further developed by Alexey Verstovsky who composed more 30 opera-vaudevilles and 6 grand operas (most of them with spoken dialogue). Later, Modest Mussorgsky worked on two comic operas, The Fair at Sorochyntsi and Zhenitba ("The Marriage"), which he left unfinished (they were completed only in the 20th century). Pyotr Tchaikovsky wrote a comic opera, Cherevichki (1885). Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov composed May Night 1878–1879 and The Golden Cockerel 1906–1907.

In the 20th century, the best examples of comic opera by Russian composers were Igor Stravinsky's Mavra (1922) and The Rake's Progress (1951), Sergey Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges (1919) and Betrothal in a Monastery (1940–1941, staged 1946), and Dmitri Shostakovich's The Nose (1927–1928, staged 1930). Simultaneously, the genres of light music, operetta, musical comedy, and later, rock opera, were developed by such composers as Isaak Dunayevsky, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Dmitri Shostakovich (Opus 105: Moscow, Cheryomushki, operetta in 3 acts, (1958)), Tikhon Khrennikov, and later by Gennady Gladkov, Alexey Rybnikov and Alexander Zhurbin.

The 21st century in Russian comic opera began with the noisy premieres of two works whose genre could be described as "opera-farce": Tsar Demyan (Царь Демьян) – A frightful opera performance. A collective project of five authors wrote the work: Leonid Desyatnikov and Vyacheslav Gaivoronsky from St. Petersburg, Iraida Yusupova and Vladimir Nikolayev from Moscow, and the creative collective "Kompozitor", which is a pseudonym for the well-known music critic Pyotr Pospelov. The libretto is by Elena Polenova, based on a folk-drama, Tsar Maksimilyan, and the work premiered on June 20, 2001, at the Mariinski Theatre, St Petersburg. Prize "Gold Mask, 2002" and "Gold Soffit, 2002".

The Children of Rosenthal (Дети Розенталя), an opera in two acts by Leonid Desyatnikov, with a libretto by Vladimir Sorokin. This work was commissioned by the Bolshoi theatre and premiered on March 23, 2005. The staging of the opera was accompanied by juicy scandal; however it was an enormous success.

English ballad and Savoy opera

[edit]England traces its light opera tradition to the ballad opera, typically a comic play that incorporated songs set to popular tunes. John Gay's The Beggar's Opera was the earliest and most popular of these. Richard Brinsley Sheridan's The Duenna (1775), with a score by Thomas Linley, was expressly described as "a comic opera".[2][3]

By the second half of the 19th century, the London musical stage was dominated by pantomime and musical burlesque, as well as bawdy, badly translated continental operettas, often including "ballets" featuring much prurient interest, and visiting the theatre became distasteful to the respectable public, especially women and children. Mr. and Mrs. Thomas German Reed, beginning in 1855, and a number of other Britons, deplored the risqué state of musical theatre and introduced short comic operas designed to be more family-friendly and to elevate the intellectual level of musical entertainments. Jessie Bond wrote,

The stage was at a low ebb, Elizabethan glories and Georgian artificialities had alike faded into the past, stilted tragedy and vulgar farce were all the would-be playgoer had to choose from, and the theatre had become a place of evil repute to the righteous British householder.... A first effort to bridge the gap was made by the German Reed Entertainers.[4]

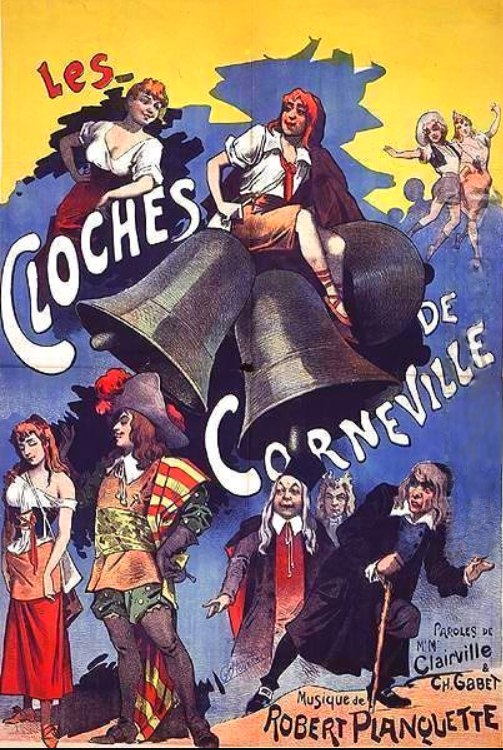

Nevertheless, an 1867 production of Offenbach's The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein (seven months after its French première) ignited the English appetite for light operas with more carefully crafted librettos and scores, and continental European operettas continued to be extremely popular in Britain in the 1860s and 1870s, including Les Cloches de Corneville, Madame Favart and others into the 1880s, often adapted by H. B. Farnie and Robert Reece.[3] F. C. Burnand collaborated with several composers, including Arthur Sullivan in Cox and Box, to write several comic operas on English themes in the 1860s and 1870s.

In 1875, Richard D'Oyly Carte, one of the impresarios aiming to establish an English school of family-friendly light opera by composers such as Frederic Clay and Edward Solomon as a countermeasure to the continental operettas, commissioned Clay's collaborator, W. S. Gilbert, and the promising young composer, Arthur Sullivan, to write a short one-act opera that would serve as an afterpiece to Offenbach's La Périchole. The result was Trial by Jury; its success launched the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership. "Mr. R. D'Oyly Carte's Opera Bouffe Company" took Trial on tour, playing it alongside French works by Offenbach and Alexandre Charles Lecocq. Eager to liberate the English stage from risqué French influences, and emboldened by the success of Trial by Jury, Carte formed a syndicate in 1877 to perform "light opera of a legitimate kind".[5] Gilbert and Sullivan were commissioned to write a new comic opera, The Sorcerer, starting the series that came to be known as the Savoy operas (named for the Savoy Theatre, which Carte later built for these works) that included H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado, which became popular around the world. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company continued to perform Gilbert and Sullivan almost continuously until it closed in 1982.

The Gilbert and Sullivan style was widely imitated by their contemporaries (for example, in Dorothy), and the creators themselves wrote works in this style with other collaborators in the 1890s. None of these, however, had lasting popularity, leaving the Savoy Operas as practically the sole representatives of the genre surviving today. Only recently, some of these other English light operas have begun to be explored by scholars and to receive performances and recordings.

North American operetta and musical comedy

[edit]

In the United States, Victor Herbert was one of the first to pick up the family-friendly style of light opera that Gilbert and Sullivan had made popular, although his music was also influenced by the European operetta composers. His earliest pieces, starting with Prince Ananias in 1894, were styled "comic operas", but his later works were described as "musical extravaganza", "musical comedy", "musical play", "musical farce", and even "opera comique". His two most successful pieces, out of more than half a dozen hits, were Babes in Toyland (1903) and Naughty Marietta (1910).[6]

Others who wrote in a similar vein included Reginald de Koven, John Philip Sousa, Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml. The modern American musical incorporated elements of the British and American light operas, with works like Show Boat and West Side Story, that explored more serious subjects and featured a tight integration among book, movement and lyrics.

In Canada, Oscar Ferdinand Telgmann and George Frederick Cameron composed in the Gilbert and Sullivan style of light opera. Leo, the Royal Cadet was performed for the first time on 11 July 1889 at Martin's Opera House in Kingston, Ontario.

The line between light opera and other recent forms is difficult to draw. Several works are variously called operettas or musicals, such as Candide and Sweeney Todd, depending on whether they are performed in opera houses or in theaters. In addition, some recent American and British musicals make use of an operatic structure, for example, containing recurring motifs, and may even be sung through without dialogue. Those with orchestral scores are usually styled "musicals", while those played on electronic instruments are often styled rock operas.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Operette001 at Theatrehistory.com, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ "The Duenna", Mary S. Van Deusen, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ a b Gillan, Don. "The Origins of Comic Opera" at the stagebeauty website, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ Bond, Jessie. Introduction to Jessie Bond's Reminiscences reprinted at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 7 November 2009

- ^ Stone, David. "Richard D'Oyly Carte", Archived 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, accessed 4 January 2009

- ^ "Victor Herbert" at the Musical Theatre Guide, accessed 4 January 2009