Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shield (geology)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

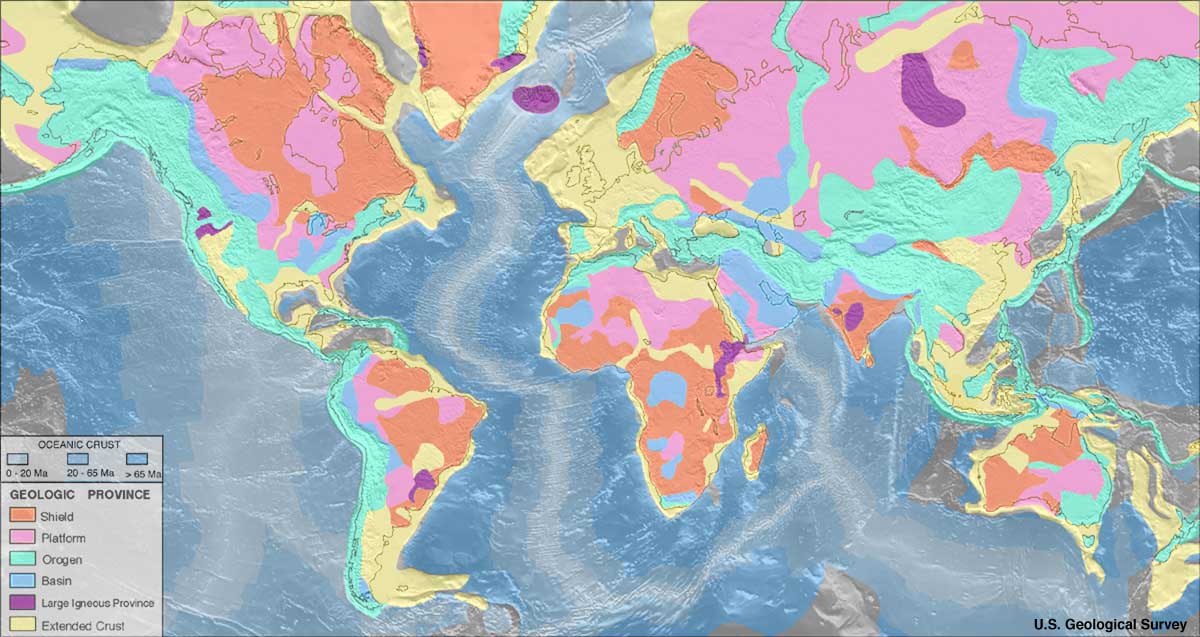

| Oceanic crust: 0–20 Ma 20–65 Ma >65 Ma |

A shield is a large area of exposed Precambrian crystalline igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks that form tectonically stable areas.[1] These rocks are older than 570 million years and sometimes date back to around 2 to 3.5 billion years.[citation needed] They have been little affected by tectonic events following the end of the Precambrian, and are relatively flat regions where mountain building, faulting, and other tectonic processes are minor, compared with the activity at their margins and between tectonic plates. Shields occur on all continents.

Terminology

[edit]

The term shield cannot be used interchangeably with the term craton. However, shield can be used interchangeably with the term basement. The difference is that a craton describes a basement overlain by a sedimentary platform while shield only describes the basement.

The term shield, used to describe this type of geographic region, appears in the 1901 English translation of Eduard Suess's Face of Earth by H. B. C. Sollas, and comes from the shape "not unlike a flat shield"[2] of the Canadian Shield which has an outline that "suggests the shape of the shields carried by soldiers in the days of hand-to-hand combat."[3]

Lithology

[edit]A shield is that part of the continental crust in which these usually Precambrian basement rocks crop out extensively at the surface. Shields can be very complex: they consist of vast areas of granitic or granodioritic gneisses, usually of tonalitic composition, and they also contain belts of sedimentary rocks, often surrounded by low-grade volcano-sedimentary sequences, or greenstone belts. These rocks are frequently metamorphosed greenschist, amphibolite, and granulite facies.[citation needed] It is estimated that over 50% of Earth's shields surface is made up of gneiss.[4]

Erosion and landforms

[edit]Being relatively stable regions, the relief of shields is rather old, with elements such as peneplains being shaped in Precambrian times. The oldest peneplain identifiable in a shield is called a "primary peneplain";[5] in the case of the Fennoscandian Shield, this is the Sub-Cambrian peneplain.[6]

The landforms and shallow deposits of northern shields that have been subject to Quaternary glaciation and periglaciation are distinct from those found closer to the equator.[5] Shield relief, including peneplains, can be protected from erosion by various means.[5][7] Shield surfaces exposed to sub-tropical and tropical climate for long enough time can end up being silicified, becoming hard and extremely difficult to erode.[7] Erosion of peneplains by glaciers in shield regions is limited.[7][8] In the Fennoscandian Shield, average glacier erosion during the Quaternary has amounted to tens of meters, though this was not evenly distributed.[8] For glacier erosion to be effective in shields, a long "preparation period" of weathering under non-glacial conditions may be a requirement.[7]

In weathered and eroded shields, inselbergs are common sights.[9]

List of shields

[edit]- The Canadian Shield forms the nucleus of North America and extends from Lake Superior on the south to the Arctic Islands on the north, and from western Canada eastward across to include most of Greenland.[10]

- The Atlantic Shield

- The Amazonian (Brazilian) Shield on the eastern bulge portion of South America. Bordering this is the Guiana Shield to the north, and the Platian Shield to the south.

- The Uruguayan Shield

- The Baltic (Fennoscandian) Shield is located in eastern Norway, Finland and Sweden.

- The African (Ethiopian) Shield is located in Africa.

- The Tuareg Shield is located in northern Africa, primarily within southern Algeria, northern Mali, and western Niger.

- The Australian Shield occupies most of the western half of Australia.

- The Arabian-Nubian Shield on the western edge of Arabia.

- The Antarctic Shield.

- In Asia, an area in China and North Korea is sometimes referred to as the China-Korean Shield.

- The Angaran Shield, as it is sometimes called, is bounded by the Yenisey River on the west, the Lena River on the east, the Arctic Ocean on the north, and Lake Baikal on the south.

- The Indian Shield occupies two-thirds of the southern Indian peninsula.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Kearey, P. (2001). The new Penguin dictionary of geology (2nd ed.). London: Penguin. p. 243. ISBN 0-14-051494-5. OCLC 59494925.

- ^ Suess, Eduard; Sollas, William Johnson; Sollas, Hertha B. C. (3 June 2018). The face of the earth (Das antlitz der erde). Oxford, Clarendon press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Miall, Andrew D. "Geological Regions". thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.

- ^ Austrheim, Håkon; Corfu, Fernando; Bryhni, Inge; Andersen, Torgeir B. (2003). "The Proterozoic Hustad igneous complex: a low strain enclave with a key to the history of the Western Gneiss Region of Norway" (PDF). Precambrian Research. 120 (1–2): 149–175. Bibcode:2003PreR..120..149A. doi:10.1016/S0301-9268(02)00167-5.

- ^ a b c Fairbridge, Rhodes W.; Finkl Jr., Charles W. (1980). "Cratonic erosion unconformities and peneplains". The Journal of Geology. 88 (1): 69–86. Bibcode:1980JG.....88...69F. doi:10.1086/628474. S2CID 129231129.

- ^ Lidmar-Bergström, Karna (1988). "Denudation surfaces of a shield area in south Sweden". Geografiska Annaler. 70 A (4): 337–350. doi:10.1080/04353676.1988.11880265.

- ^ a b c d Fairbridge, Rhodes W. (1988). "Cyclical patterns of exposure, weathering and burial of cratonic surfaces, with some examples from North America and Australia". Geografiska Annaler. 70 A (4): 277–283. doi:10.1080/04353676.1988.11880257.

- ^ a b Lidmar-Bergström, Karna (1997). "A long-term perspective on glacial erosion". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 22 (3): 297–306. Bibcode:1997ESPL...22..297L. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9837(199703)22:3<297::AID-ESP758>3.0.CO;2-R.

- ^ Nenonen, Keijo; Johansson, Peter; Sallasmaa, Olli; Sarala, Pertti; Palmu, Jukka-Pekka (2018). "The inselberg landscape in Finnish Lapland: a morphological study based on the LiDAR data interpretation". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Finland. 90 (2): 239–256. doi:10.17741/bgsf/90.2.008.

- ^ Merriam, D. F. (2005). Encyclopedia of Geology. Selley, Richard C., 1939-, Cocks, L. R. M. (Leonard Robert Morrison), 1938-, Plimer, I. R. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic. p. 21. ISBN 9781601193674. OCLC 183883048.