Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Criminal record.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Criminal record

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Criminal record

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

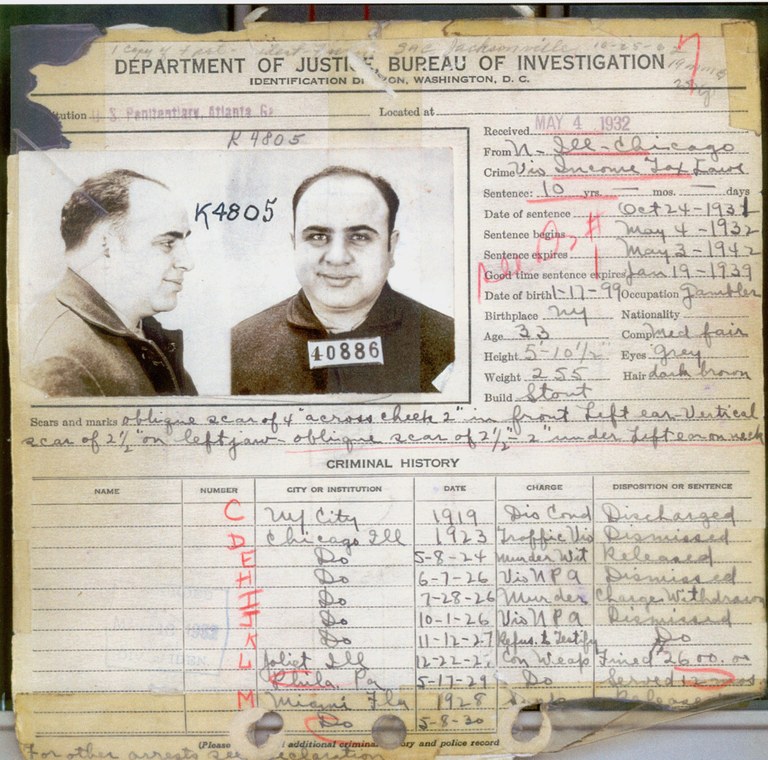

A criminal record is an official compilation of information collected by criminal justice agencies on individuals, consisting of identifiable descriptions and notations of arrests, detentions, indictments, or other formal criminal charges, along with dispositions such as acquittals, sentencing, correctional supervision, or other outcomes.[1] Maintained primarily by law enforcement, courts, and probation departments, these records serve to track prior offenses for purposes including enhanced sentencing in recidivism cases, parole eligibility assessments, and public safety evaluations during investigations.[2] In many jurisdictions, records distinguish between convictions—which form the core of permanent entries—and non-convictions like arrests without charges, though the latter may persist in some databases unless expunged or sealed through legal processes.[3]

The contents of a criminal record typically encompass the individual's demographics, offense classifications (e.g., felonies or misdemeanors), dates of incidents and court proceedings, and imposed penalties such as fines, probation terms, or incarceration periods, with federal systems often integrating state-level data via identifiers like FBI numbers.[2] Jurisdictional variations are significant; for instance, some U.S. states limit dissemination of juvenile records or allow automatic sealing after sentence completion for non-violent offenses, while others maintain broader access for employers and licensing bodies.[4] Internationally, equivalents like France's casier judiciaire focus more narrowly on convictions post-appeal, excluding unproven allegations to prioritize rehabilitative privacy.[5]

Criminal records exert substantial causal influence on post-conviction life trajectories by informing decisions in employment, housing, and professional licensing, where empirical studies link record disclosure to rejection rates exceeding 50% in certain sectors, thereby hindering economic stability and elevating recidivism risks through reduced legitimate opportunities.[6] Controversies arise from incomplete or erroneous entries persisting despite corrections, as well as debates over "ban the box" policies that delay record inquiries to mitigate initial bias, though evidence indicates such measures yield mixed results in altering hiring outcomes without addressing underlying enforcement disparities.[7] Expungement mechanisms exist to mitigate these effects for eligible low-level offenses, reflecting a tension between public safety imperatives and empirical recognition that lifelong stigmatization undermines desistance from crime.[8]

At the federal level, the Clean Slate Act was reintroduced in April 2025 to enable automatic sealing of certain non-violent federal convictions after waiting periods, though it remains pending without passage.[175] The Fresh Start Act, also introduced in 2025, proposes grants to states for automated record relief infrastructure.[176] These trends reflect a policy shift toward proactive clearance to address administrative backlogs—millions remain eligible but unprocessed under petition systems—while proponents cite empirical data linking record visibility to 50-75% lower employment rates for ex-offenders, though critics question enforcement feasibility and potential concealment of recidivism risks from employers and the public.[177][178]

Definition and Fundamentals

Definition

A criminal record, also referred to as a criminal history record or "rap sheet," constitutes an official compilation of documented interactions an individual has had with the criminal justice system, primarily focusing on arrests, charges, convictions, and associated sentences maintained by law enforcement or governmental agencies.[9][6] In the United States, federal regulations define criminal history record information as data collected by criminal justice agencies on individuals, including identifiable descriptions, notations of arrests, and details of judicial proceedings such as indictments, convictions, or acquittals.[10] This record serves as a factual ledger of proven or alleged criminal conduct, with entries typically verified through fingerprints or other biometric identifiers to ensure accuracy in linking events to specific persons.[11] Core elements of a criminal record generally encompass the date and location of offenses, the nature of charges (e.g., felonies or misdemeanors), court dispositions, and penalties imposed, such as incarceration, probation, or fines.[6] However, jurisdictions differ in scope: some, like Washington State, explicitly include citations, arrests based on probable cause, and even non-conviction records if they relate to criminal conduct, while others limit entries to adjudicated convictions to mitigate overreach.[12] Nevada statutes, for instance, describe it as information from records maintained by criminal justice entities, emphasizing arrests and convictions without mandating inclusion of dismissed charges unless specified.[13] These variations arise from statutory frameworks balancing public access for safety against privacy protections, with federal systems like the FBI's National Crime Information Center aggregating state-level data for interstate consistency.[9] Internationally, definitions align with similar principles but adapt to local legal traditions; for example, records may exclude juvenile offenses or spent convictions under rehabilitation schemes, reflecting empirical evidence that indefinite retention can hinder reintegration without proportionally enhancing deterrence. Despite these nuances, a defining feature across systems is the reliance on verifiable court or agency documentation, excluding unadjudicated allegations to uphold due process and causal accuracy in attributing criminal liability.[5]Core Components

The core components of a criminal record encompass the documented elements of an individual's interactions with the criminal justice system, primarily focusing on arrests, charges, dispositions, and sanctions. These records are maintained by law enforcement, courts, and correctional agencies to track criminal history, with variations across jurisdictions but consistent foundational elements. Identifying information forms the basis, including the subject's full name, aliases, date of birth, sex, race or ethnicity, physical descriptors (such as height, weight, and eye color), and biometric identifiers like fingerprints or photographs, which enable accurate matching across systems.[14][15] Arrest records constitute a primary component, detailing the date and location of apprehension, the arresting agency (e.g., local police or federal authorities), the circumstances of the arrest, and the specific offenses charged at booking. These entries often include booking photographs ("mug shots") and fingerprint impressions submitted to centralized databases like the FBI's Next Generation Identification system. Charges follow, specifying statutory violations, such as felonies or misdemeanors, with codes referencing relevant laws (e.g., under the U.S. Code or state penal codes).[16][6][17] Judicial dispositions represent the outcomes of charges, including convictions (guilty pleas or verdicts), acquittals, dismissals, diversions, or deferred adjudications, along with the presiding court, judge, and date of resolution. For convictions, records note the offense level (e.g., felony class) and any plea bargains. Sentencing details complete this phase, recording imposed penalties such as incarceration terms (with start and end dates), fines, probation conditions, restitution orders, or community service requirements; post-release supervision like parole is also tracked if applicable.[18][15][19] Additional components may include updates for record accuracy, such as expungements, pardons, or corrections to dispositions, though these do not erase underlying events from certain federal or state repositories. In the U.S., the FBI's Identity History Summary (rap sheet) standardizes these elements nationally, compiling data from contributing agencies while noting incomplete or pending information. Jurisdictional differences persist—for instance, some states limit inclusion of non-conviction arrests post a statutory period, but core records prioritize verifiable justice system events over unsubstantiated allegations.[20][16]Distinctions from Related Records

A criminal record specifically documents formal convictions for violations of criminal law, typically resulting from a guilty plea or trial verdict establishing guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, and includes details such as the offense, sentence imposed, and date of adjudication.[7] In contrast, an arrest record merely chronicles an individual's apprehension by law enforcement based on probable cause of criminal activity, without implying guilt or a final judicial outcome; arrests that do not proceed to conviction—due to dismissal, acquittal, or lack of charges—do not contribute to a criminal record.[21] This distinction is critical because arrest records can persist independently and may appear in background checks, potentially stigmatizing individuals absent proven wrongdoing, whereas criminal records reflect adjudicated culpability.[22] Relatedly, police records or incident reports differ by capturing raw investigative details, witness statements, and circumstances of alleged crimes without judicial validation; these are operational logs maintained by law enforcement for internal use rather than public or formal conviction histories.[23] A rap sheet, often used interchangeably with criminal record in colloquial terms, comprises a summary of both arrests and convictions from fingerprint-based submissions to centralized databases, but its inclusion of non-conviction data can blur lines with broader criminal history reports unless filtered for dispositions.[24] Unlike these, criminal records exclude unadjudicated arrests or mere police contacts, emphasizing only entries verified through court processes to align with principles of due process and presumption of innocence until proven guilty.[25] Criminal records must also be differentiated from civil records, which pertain to non-criminal disputes such as contracts, torts, or family matters resolved by preponderance of evidence standards, yielding remedies like monetary damages or injunctions rather than penal sanctions like imprisonment or fines tied to public offenses. Civil judgments do not denote criminality and thus fall outside criminal record repositories, though overlapping conduct (e.g., a fraud case with both civil and criminal tracks) may generate parallel but distinct documentation. This separation upholds the higher evidentiary threshold and societal condemnation inherent to criminal proceedings over civil liabilities. For offenses involving minors, juvenile records operate under specialized systems prioritizing rehabilitation over punishment, with adjudications termed "delinquency" rather than convictions; these do not equate to adult criminal records and are frequently sealed or expunged upon reaching majority to avoid lifelong barriers, reflecting empirical evidence that adolescent neurodevelopment warrants distinct treatment from adult culpability.[26] In jurisdictions like New York, youthful offender statuses for 16- to 18-year-olds result in automatically sealed records, insulating them from adult criminal record classifications even for serious acts.[27] Such delineations prevent conflation of rehabilitative interventions with punitive adult histories, supported by data showing juvenile records' limited public accessibility to foster reintegration.Historical Development

Origins and Early Systems

The earliest precursors to criminal records appeared in ancient Mesopotamia, where cuneiform clay tablets from the third millennium BC documented specific judicial rulings, trials, and punishments alongside legal codes like that of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100 BC).[28] These artifacts, preserved in archives such as those from Sumerian cities, recorded case outcomes for administrative and evidentiary purposes but lacked centralized tracking of individuals across incidents, functioning primarily as isolated ledgers of state or temple justice rather than personal offender dossiers.[29] In medieval Europe, particularly England from the 12th century, court rolls emerged as rudimentary systems for logging crimes and convictions, with royal itinerant courts (eyres) from 1194 to 1348 producing detailed rolls of pleas, presentments, and sentences for felonies like homicide and theft. Clerks inscribed these on parchment membranes, often in Latin, to facilitate fine collection and royal oversight, as seen in the Pipe Rolls and King's Bench records starting around 1200. However, these were jurisdiction-specific, accusatory in nature—requiring victims or communities to initiate proceedings—and did not aggregate lifelong criminal histories or enable cross-regional recidivism checks, reflecting a decentralized feudal structure where enforcement depended on local manorial or shire courts rather than state bureaucracies.[30] No formal registries for individual criminal careers existed before the early modern period; medieval records prioritized immediate fiscal and punitive resolution over preventive surveillance.[31] Developments in 18th-century England marked a transition, with hulks registers logging prisoner details like age from the 1770s and London sheriffs inventing criminal registers to catalog convictions more consistently amid rising urban crime and transportation practices.[32] Similarly, in colonial America and early U.S. locales, pre-1850 records comprised ad hoc notes by constables or watchmen, stored informally at jails or precincts without standardization.[33] These early mechanisms laid groundwork for later systems by institutionalizing written accountability, though their incompleteness stemmed from limited mobility, literacy, and state capacity.Modern Standardization (19th-20th Centuries)

The professionalization of police forces in the 19th century, driven by urbanization and rising crime rates in industrializing nations, necessitated standardized systems for identifying and tracking criminals to combat recidivism effectively. Prior to this, records were often localized and inconsistent, relying on descriptions or photographs without uniform metrics. In France, Alphonse Bertillon, a clerk at the Paris Prefecture of Police, developed anthropometry—known as the Bertillon system—in 1879, introducing precise measurements of 11 skeletal features (such as arm length, head width, and middle finger length) combined with standardized frontal and profile photographs, termed mugshots.[34][35] This method enabled classification and retrieval from centralized files, marking an early step toward modern record standardization by assuming bodily dimensions stabilized after puberty, thus allowing reliable matching across arrests.[36] Bertillonage rapidly gained international adoption; by the 1880s, it was implemented in major U.S. cities like New York and Chicago, as well as in Europe and South America, supplanting less systematic approaches and facilitating inter-jurisdictional record sharing.[37][38] However, its limitations became evident, including measurement errors due to human variability and the need for trained technicians, prompting a shift to more objective biometrics. In the late 19th century, British scientist Francis Galton advanced the scientific basis for fingerprints, demonstrating their uniqueness and permanence through empirical studies of ridge patterns.[39] This culminated in practical adoption: Argentina's police used fingerprints for a criminal identification in 1892 under Juan Vucetich, while the United Kingdom officially integrated them into Scotland Yard's procedures by 1901, phasing out anthropometry.[39][40] By the early 20th century, fingerprinting dominated as the cornerstone of criminal record standardization, enabling automated classification systems like the Henry classification scheme used in Britain and exported globally. In the United States, early adopters included the New York City Police Department in 1903, but true national standardization arrived with the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) establishment of its Identification Division on July 1, 1924, which centralized fingerprint cards from federal penitentiaries and state agencies, amassing millions of records for cross-referencing.[41][40][42] This federal repository addressed fragmented state-level systems, improving accuracy and efficiency in verifying identities and prior convictions, with the division processing over 700,000 cards annually by the 1930s.[43] Such developments reflected a causal emphasis on empirical identifiability to enhance public safety, though challenges like incomplete submissions persisted until later reforms.[44]Digital Era and Recent Reforms (Post-2000)

The transition to digital criminal records accelerated post-2000, driven by advancements in database technology and federal initiatives in the United States. The FBI's implementation of the Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS) in 1999 marked the onset of widespread digitization, enabling electronic storage and rapid querying of fingerprint and criminal history data across agencies.[43] By 2014, the FBI had digitized millions of files, including criminal history records dating to the early 1900s, as part of a modernization effort to replace paper-based systems with searchable electronic formats.[45] This shift extended to national systems like the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), a computerized index aggregating arrest, incarceration, and other justice data from federal, state, and local sources, facilitating real-time access for law enforcement.[46] Digitization enhanced efficiency but introduced challenges related to accessibility and permanence. Public court records, once requiring physical retrieval, became instantly available online, with state courts releasing over 147 million records annually by the early 2020s, often scraped into private commercial databases.[47] This proliferation perpetuated collateral consequences, as expunged or sealed records frequently persisted in third-party databases, undermining relief efforts and imposing what critics term "digital punishment" through barriers to employment and housing.[48] [47] Discrepancies between official state records and private checks further complicated accuracy, with studies revealing inconsistencies in up to 70% of cases due to incomplete data aggregation.[49] In response, reforms emphasized automated clearance and reintegration, adapting to digital realities. Since 2018, 11 U.S. states have enacted "clean slate" laws providing automatic expungement or sealing for eligible non-violent convictions after waiting periods, such as five to seven years crime-free, to mitigate online visibility without manual petitions.[50] Between 2019 and 2021 alone, over 400 new record-relief measures were adopted across states, expanding eligibility for marijuana-related offenses and misdemeanors amid cannabis legalization.[51] Empirical analysis from Michigan's 2018 expansion showed expunged individuals gained employment and earnings boosts of 20-30% without elevating recidivism rates, supporting causal links between record relief and reduced reoffending incentives.[52] Emerging tools, including AI-driven corrections for record errors, aim to improve data integrity in these systems.[53] Internationally, frameworks like the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (2018) imposed stricter controls on processing criminal data, requiring proportionality and erasure rights, though enforcement varies.[54]Purposes and Rationales

Public Safety and Risk Assessment

Criminal records serve as a primary data source for evaluating an individual's risk of future criminal behavior, thereby supporting decisions aimed at protecting public safety, such as pretrial release, sentencing, parole, and supervision levels.[55] Actuarial risk assessment tools, which integrate elements of criminal history like the number, recency, and severity of prior convictions, have demonstrated empirical validity in predicting recidivism, with criminal history emerging as one of the strongest static predictors across multiple studies.[56] [57] For instance, meta-analyses of offender recidivism consistently find that individuals with extensive prior records exhibit recidivism rates substantially higher than first-time offenders; in federal data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission, offenders with no prior criminal history had a rearrest rate of 6.8% within eight years, compared to 17.2% for those with minor priors and higher for those with more serious histories.[58] In practice, tools like the Level of Service Inventory-Revised (LSI-R) and the Public Safety Assessment (PSA) quantify risk by weighting criminal record factors—such as prior violent offenses or failure to appear—against dynamic variables, enabling jurisdictions to allocate resources efficiently, such as intensifying supervision for high-risk individuals to reduce community harm.[55] Bureau of Justice Statistics analyses of state prisoners released in 2012 showed that those with prior convictions faced rearrest rates up to 83% within five years, underscoring the causal link between historical offending patterns and future risk, which informs policies like denying bail to repeat violent offenders.[59] These assessments prioritize public safety by identifying low-risk individuals for alternatives to incarceration, as evidenced in Kentucky's PSA implementation, where structured use correlated with reduced pretrial misconduct without compromising safety metrics.[60] Empirical evaluations affirm that incorporating criminal records into risk models outperforms clinical judgment alone, with meta-analytic effect sizes for criminal history variables often exceeding those of demographic or psychological factors, though overall predictive accuracy remains moderate (AUC values typically 0.65-0.75), limited by base rate issues and incomplete data.[61] [57] Critics from advocacy groups argue tools may perpetuate disparities, but rigorous studies attribute much of this to genuine risk signals in records rather than bias, as validated instruments control for confounders and focus on behavioral history over protected traits.[62] Deployment of such systems has yielded tangible safety gains, including lower recidivism in supervised populations; for example, structured risk-based parole decisions have been linked to 10-20% reductions in reoffending compared to unstructured approaches in longitudinal state evaluations.[55]Deterrence and Incentive Structures

Criminal records theoretically contribute to specific deterrence by imposing persistent collateral consequences that elevate the expected costs of future offending, including restricted access to employment, housing, and social welfare. These enduring penalties, such as statutory bars on occupational licensing or ineligibility for public benefits, signal to convicted individuals that prior crimes yield long-term repercussions, potentially incentivizing behavioral reform to mitigate further disadvantages. For example, in jurisdictions like the United States, federal and state laws attach over 44,000 collateral sanctions to convictions, many of which persist indefinitely unless explicitly relieved.[63] Empirical evidence, however, indicates that these structures often fail to deter and may instead promote recidivism by creating criminogenic barriers that hinder reintegration. A seminal audit study found that job applicants with criminal records in Milwaukee received 50% fewer employer callbacks than comparable applicants without records, with the disparity reaching 75% for black applicants, exacerbating unemployment and associated risks of reoffending.[64] Econometric research bounding causal effects estimates that employment denials triggered by criminal background checks raise three-year recidivism probabilities by 7 to 11 percentage points, as excluded individuals face heightened economic desperation without viable legal pathways to stability.[65] Incentive mechanisms tied to records, such as eligibility for expungement or sealing after demonstrated rehabilitation, aim to reward desistance but show mixed efficacy due to low uptake and selection effects. A study of Pennsylvania's set-aside process revealed that only 6.5% of eligible individuals obtained relief within five years, yet recipients exhibited a 7.1% rearrest rate over that period—substantially below rates for denied applicants (around 20-30% in similar cohorts)—suggesting that record relief can lower reoffending when accessed, though self-selection among low-risk individuals confounds interpretations.[66] Conversely, the opacity and severity of unmitigated records correlate with sustained criminal involvement, as collateral exclusions incentivize informal economies prone to illegality rather than lawful compliance.[67] Broader incentive structures leverage records for general deterrence by publicizing conviction histories, enabling employers, landlords, and communities to adjust behaviors and thereby increase the certainty of social and economic sanctions for potential offenders. Yet, systematic reviews of sanction severity find weak overall deterrent impacts from such non-custodial penalties, with recidivism patterns more strongly predicted by prior history than by record visibility alone.[68] Peer-reviewed analyses consistently highlight that while records facilitate risk-based exclusions for public safety, their net effect on individual incentives often tilts toward recidivism amplification, underscoring the tension between punitive permanence and rehabilitative pragmatism.[69]Empirical Evidence for Efficacy

Criminal history serves as a robust static predictor of recidivism, with meta-analyses confirming its association with future offending across diverse offender populations. For instance, extensive prior convictions correlate with recidivism rates 2-3 times higher than for first-time offenders, as evidenced in longitudinal studies tracking releasees over 3-5 years.[70] Actuarial risk assessment tools incorporating criminal record data, such as the Level of Service Inventory-Revised (LSI-R), demonstrate moderate predictive validity (AUC values of 0.65-0.70), outperforming clinical judgment alone in forecasting general recidivism within 1-3 years post-release.[71] These findings hold in community-supervised samples, where criminal history explains up to 20% of variance in re-arrest outcomes, supporting the use of records for targeted supervision and resource allocation to mitigate public safety risks.[72] In employment contexts, disclosure of criminal records enables employers to conduct background checks that reduce hiring of high-risk individuals, thereby lowering workplace recidivism incidents. A study of over 1,000 applicants found that denying employment based on criminal history decreased subsequent arrests by approximately 10-15% for those affected, as alternative opportunities were pursued without immediate desperation-driven crime.[65] Conversely, policies restricting early disclosure, such as "ban-the-box" laws implemented in jurisdictions like New York City from 2013 onward, have shown no net increase in employment for those with records and correlated with 3-5% rises in low-skilled job callbacks for minority applicants without records, potentially displacing safer hires and elevating overall crime rates by 4% in affected labor markets.[73][74] Empirical bounding of causal effects indicates that while non-disclosure may temporarily boost initial job attainment, it undermines long-term public safety by obscuring recidivism risks, with drug-related arrests increasing post-policy in states like Minnesota.[75] Regarding deterrence, criminal records contribute indirectly through incentive structures by signaling persistent risk and limiting access to licit opportunities, which meta-reviews link to reduced offending via opportunity costs rather than direct fear of record accrual. Offenders with visible records face 40-50% employment barriers, prompting desistance in 20-30% of cases via "stakes in conformity," though this efficacy diminishes after 7-10 crime-free years when recidivism risk aligns with non-offenders'.[64][76] However, criminology literature, often influenced by rehabilitation paradigms, overstates reformist interventions while underemphasizing records' role in certainty-based deterrence; rigorous panel data affirm that record-enabled sanctions (e.g., licensing denials) yield elastic responses, with a 10% increase in perceived detection probability reducing crime by 3-7%.[77] Overall, evidence supports records' efficacy for risk stratification over blanket expungement, though trade-offs exist in recidivism elevation from employment exclusion, resolvable via time-bound redemption thresholds informed by aging-out curves.[78]Creation and Management

Recording Processes

The recording of a criminal record begins at the point of arrest, when law enforcement agencies document the incident through the booking process. Suspects are fingerprinted, photographed (often via mugshots), and subjected to biometric capture, with personal details such as full name, aliases, date of birth, physical description, and demographic information recorded alongside the offense details, arrest date, and charging agency.[79] This initial data entry occurs in local police or sheriff department systems, creating a preliminary arrest record that serves as the foundation for subsequent updates.[80] Fingerprints and associated data are then transmitted to centralized state or provincial repositories for identification against existing records, enabling linkage to prior offenses if applicable; in systems without matches, a new criminal history file is initiated.[81] In the United States, this often involves submission to the FBI's Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division via state identification bureaus, which maintain the Interstate Identification Index (III) for interstate record sharing.[82] Internationally, analogous processes occur through national police databases, such as the UK's Police National Computer or Australia's National Criminal History Record Check system, where arrests trigger automated or manual data uploads emphasizing fingerprint and DNA biometrics for accuracy.[16] Upon progression to court, the record is updated iteratively: prosecutors file charges, which are appended to the file, followed by disposition reporting after plea, trial, or dismissal. Convictions and sentences—detailing verdict date, offense classification, penalty imposed (e.g., incarceration term or probation duration), and court jurisdiction—are reported by judicial clerks, probation offices, or arresting agencies to the originating law enforcement entity and higher-level repositories, typically within 30-90 days depending on jurisdiction-specific mandates.[83] These updates employ standardized formats like the FBI's Disposition File Maintenance Submission (DSPE), which includes biographic and outcome data to ensure completeness and prevent incomplete arrest-only entries from persisting indefinitely.[82] Maintenance protocols require periodic validation, with agencies responsible for correcting errors through audits or individual challenges; for instance, U.S. states must comply with FBI uniformity standards under 28 CFR Part 20, mandating timely reporting of final dispositions to avoid discrepancies in national queries.[16] Non-conviction dispositions, such as acquittals or charges dropped, may trigger partial sealing or purging in some jurisdictions (e.g., automatic under certain U.S. state laws post-2010 reforms), but arrests often remain in summary histories unless formally expunged via court order.[84] Technological integration, including automated fingerprint identification systems (AFIS), facilitates real-time cross-jurisdictional checks, reducing duplication while enhancing causal traceability of offenses to individuals.[85]Technological Infrastructure and Accuracy

The technological infrastructure for criminal records primarily consists of centralized databases managed by national law enforcement agencies, interconnected with state and local systems to facilitate data sharing. In the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division operates the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), a computerized index aggregating criminal history, fugitive, stolen property, and missing persons data reported by law enforcement agencies nationwide.[86] [46] Complementing NCIC is the Interstate Identification Index (III), which links state repositories for fingerprint-based criminal history checks, while the Next Generation Identification (NGI) system integrates advanced biometrics such as fingerprints, palm prints, iris scans, and facial recognition to enhance identification accuracy beyond traditional alphanumeric records.[87] These systems rely on secure wide-area networks and are increasingly incorporating cloud-based models for on-demand access, though compliance with CJIS Security Policy mandates strict encryption and access controls to mitigate risks.[88] [89] Globally, infrastructure varies by jurisdiction but often features similar biometric-enabled repositories; for instance, Interpol's systems enable cross-border fingerprint and DNA matching, while countries like those in the European Union leverage shared databases under frameworks such as the Schengen Information System for harmonized criminal data exchange.[90] Biometric integration, including automated fingerprint identification and facial recognition, has improved linkage of records to individuals, reducing reliance on name-based matches prone to homonyms, with NGI processing millions of daily transactions for real-time verification.[91] [92] Despite these advancements, accuracy remains challenged by data entry errors, interoperability gaps, and aggregation issues across public and private sectors. A 2024 analysis of 101 sampled criminal records revealed significant discrepancies, with private background check reports showing false positives (non-matching charges) in up to 74% of reported offenses when compared to official state repositories, often due to mismatched identities or unverified bulk data scraping.[93] [94] Official FBI systems like the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) exhibit false negatives, particularly for delayed arrests occurring more than a day after incidents, as reporting lags prevent timely inclusion.[95] Multi-level studies tracking thousands of criminal events across databases highlight systemic errors from manual inputs, outdated dispositions (e.g., unupdated acquittals), and private data brokers amplifying inaccuracies through incomplete aggregation, leading to erroneous denials in employment and housing.[96] [97] Remediation efforts, such as AI-driven error correction in records management systems, aim to address these, but persistent human and procedural factors underscore the need for standardized validation protocols to ensure causal reliability in record-based decisions.[53]Juvenile and Specialized Records

Juvenile criminal records are typically handled with greater confidentiality than adult records to facilitate rehabilitation and reduce lifelong stigma for minors, whose brains and decision-making capacities are developmentally immature compared to adults. In the United States, juvenile records are governed by state laws emphasizing non-public access, with confidentiality often enshrined as a core principle to prevent records from becoming public unless exceptions apply, such as for serious violent offenses or transfer to adult court.[98] [99] This approach stems from the rehabilitative ethos of juvenile justice systems, established in the early 20th century, which prioritizes intervention over punishment, though empirical data on long-term outcomes shows mixed results, with confidentiality aiding access to education and employment but exceptions eroding privacy protections.[100] [101] Sealing and expungement represent key mechanisms for limiting juvenile record visibility, distinct in legal effect: sealing restricts public and some governmental access while preserving records for law enforcement, whereas expungement involves physical or digital destruction, rendering the offense legally nonexistent. As of 2020, only a minority of U.S. states provide automatic sealing or expungement for juvenile records upon reaching adulthood or case closure, such as at age 18 or after disposition expiration, with processes varying by offense severity—misdemeanors often qualify more readily than felonies.[102] [103] For instance, California's courts automatically seal certain non-violent juvenile cases, while petitioners must apply for others, requiring demonstration of rehabilitation and no subsequent offenses, typically after age 18.[104] Internationally, similar protections exist; China's 2022 Implementation Measures mandate sealing of juvenile criminal files, including electronic archives, upon case termination or age 18, excluding severe cases like homicide.[105] Exceptions persist for public safety, such as disclosure to schools or employers in high-risk scenarios, undermining absolute confidentiality and potentially perpetuating barriers despite policy intent.[99][100] Specialized records encompass subsets of criminal histories maintained for targeted monitoring, often overriding general sealing provisions due to heightened public safety risks, with sex offender registries exemplifying this category. In the U.S., federal law under the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) requires registration for convictions involving sexual offenses with physical contact, such as rape or sexual assault, with states like New York classifying offenders into three risk levels—low (Level 1, 20-year registration), moderate (Level 2), and high (Level 3, lifetime)—based on recidivism assessments, including designations as sexual predators or sexually violent offenders.[106] [107] These registries are publicly accessible online, enabling community notification, though juvenile sex offenders may qualify for limited confidentiality if adjudicated in juvenile court, with transfers to adult systems exposing them to full registration.[108] Empirical critiques note that broad registries may not proportionally reduce recidivism, as studies indicate registered offenders face twice the re-arrest risk from stigma-induced instability, yet they persist for deterrence and victim protection rationales.[109] Other specialized records include those for domestic violence or firearms prohibitions, though less uniformly public than sex offender lists; for example, federal prohibitions under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g) bar felons from possession without a dedicated registry, relying instead on background checks cross-referencing general records. Juvenile specialized records, when unsealed for grave offenses like murder, integrate into adult systems, balancing rehabilitation with accountability, as evidenced by state variations where only 10 U.S. jurisdictions maintain full confidentiality regardless of offense gravity.[110] Management of these records emphasizes technological separation, with law enforcement retaining access for risk assessment, though inaccuracies from legacy systems persist, highlighting tensions between privacy and causal prevention of repeat harms.[111]Access, Disclosure, and Utilization

Legal Frameworks for Access

Access to criminal records is regulated by statutes that restrict dissemination to authorized entities, primarily law enforcement, courts, and employers for specific purposes, to balance public safety against individual privacy rights. In the United States, no comprehensive federal law standardizes non-criminal justice access; instead, the National Crime Prevention and Privacy Compact (enacted 1998) facilitates interstate sharing among state repositories while imposing confidentiality safeguards.[112] Federal access is permitted for national security positions under 5 U.S.C. § 9101, allowing agencies to query FBI records for eligibility in sensitive roles.[113] State laws govern most civilian access, with variations in disclosure requirements; for instance, many states mandate criminal history checks for certain licenses but prohibit blanket employer inquiries into non-conviction data to mitigate discriminatory impacts.[114] In the European Union, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, effective 2018) classifies criminal conviction data as sensitive, prohibiting processing except under explicit member-state laws or official authority oversight, with comprehensive registers controlled solely by public bodies.[115] Article 10 requires that any access for employment or other non-judicial uses comply with national legislation, often limiting disclosures to relevant offenses and prohibiting routine checks absent legal basis, to prevent disproportionate privacy intrusions.[116] Implementation differs across states; for example, Germany's Federal Data Protection Act permits limited employer access for fiduciary positions, while France's casier judiciaire system restricts bulletins to authorized requesters like judiciary or specific professions.[117] The United Kingdom operates a tiered Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) framework under the Police Act 1997 (as amended), enabling basic, standard, and enhanced checks for employers, with disclosures scaling by role risk—basic checks reveal only unspent convictions under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974, while enhanced include police intelligence for vulnerable groups.[118] Post-Brexit, UK GDPR mirrors EU restrictions on criminal data processing, confining it to lawful bases like substantial public interest, with the Information Commissioner's Office enforcing against unauthorized retention or sharing.[119] Internationally, frameworks diverge further: Australia's national police checks under the Spent Convictions Scheme limit disclosures of minor offenses after rehabilitation periods, Canada's Criminal Records Act allows pardoned convictions to be sealed from most checks, and the Netherlands restricts access via the Judicial Documentation System to judicial or vetted professional needs, reflecting broader emphasis on proportionality over uniform openness.[120] These variations underscore no global standard, with common themes of restricting access to "need-to-know" parties to curb stigma while enabling risk mitigation.[121]Employment and Background Checks

Employers commonly incorporate criminal background checks into hiring processes to evaluate applicants' potential risks, particularly for roles involving financial responsibility, public interaction, or safety. These checks search databases of arrests, convictions, and court dispositions, often through consumer reporting agencies, to identify patterns of behavior that may correlate with workplace unreliability or harm. In the United States, approximately 70 to 100 million adults—or one in three—possess some form of criminal record, making such screenings a widespread tool despite varying predictive validity.[122] Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), employers must obtain applicants' written consent prior to obtaining criminal history reports and notify individuals if adverse decisions are based on the findings, allowing opportunities to dispute inaccuracies. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) enforces Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, prohibiting employment practices with disparate impacts on protected groups unless justified by business necessity; this requires individualized assessments weighing offense severity, rehabilitation evidence, time elapsed since conviction, and job relevance rather than categorical bans. Recent EEOC regulations, effective as of late 2024, further limit reliance on arrest records without convictions and emphasize validated risk assessments over blanket policies. Compliance failures have led to multimillion-dollar settlements, underscoring legal risks for non-adherence.[123][124][125] Empirical studies reveal limited generalizability in using criminal records to forecast workplace misconduct. Analysis of over 300,000 retail employees found no overall association between disclosed criminal histories and performance metrics like termination for cause, though job-specific variations emerged—such as elevated misconduct-related turnover among sales staff with records. Similarly, longitudinal tracking of hires with records showed no heightened rates of on-the-job violations compared to peers, challenging assumptions of broad recidivism risk in non-criminal employment contexts. These findings suggest that while records may signal elevated risks in high-stakes roles (e.g., theft history for cash-handling positions), they often fail to predict behavior in low-risk jobs, prompting debates over over-reliance amid error-prone databases reporting outdated or expunged data.[126][127] Internationally, practices diverge sharply due to privacy laws and cultural norms. In the European Union, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) restricts processing criminal data to proportionate, necessary uses, often requiring explicit justification and limiting pre-employment inquiries unless legally mandated. Countries like Canada and Australia mandate police certificates for visa-linked employment but permit broader checks via private vendors, while nations such as Indonesia issue formal "no record" certificates for civil service applications. Global employers conducting cross-border hires face fragmented compliance, with services scanning records from up to 200 countries, though accessibility varies—e.g., incomplete in regions with decentralized or corrupt registries.[128][129]Applications in Housing, Licensing, and Travel

In the United States, criminal records significantly impede access to rental housing, as private landlords routinely perform background checks and frequently reject applicants with convictions, particularly for felonies or recent offenses, affecting an estimated 70 million individuals with arrest or conviction histories.[130] Public housing authorities (PHAs), governed by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) regulations, impose mandatory lifetime bans for convictions related to methamphetamine production or distribution and discretionary three-year exclusions for other drug-related crimes, though HUD guidance since 2016 prohibits blanket denials to avoid disparate impact violations under the Fair Housing Act.[131] [132] These policies stem from statutory requirements under the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act of 1998, which authorize PHAs to screen for threats to resident safety, but implementation varies, with some jurisdictions applying individualized assessments rather than automatic exclusions.[133] For professional and occupational licensing, state boards often deny or condition approvals based on criminal histories deemed indicative of unfitness, such as crimes of moral turpitude in fields like medicine, law, or nursing, where 35 states plus the District of Columbia limit board authority to unrelated convictions as of recent analyses.[134] Examples include automatic disqualifications for certain felonies in cosmetology or real estate licensing in unreformed states, though reforms in over 20 states since 2019 require a "direct relation" between the offense and the licensed profession, aiming to reduce blanket barriers that affect up to one-third of adults with records.[135] [122] Driver's licenses face fewer restrictions post-conviction unless tied to specific offenses like DUI, but revocation or denial persists for habitual traffic violators with criminal driving records.[136] Criminal records constrain international travel primarily through foreign visa and entry policies, as over 40 countries, including Canada and Australia, bar individuals with sentences exceeding 12 months for serious crimes or drug offenses, requiring disclosure via police certificates during applications.[137] [138] U.S. citizens retain passport eligibility absent specific revocations, but registered sex offenders convicted of child exploitation offenses must notify authorities 21 days prior to foreign travel under the International Megan's Law of 2016, with passports marked by a unique identifier to alert destination countries.[139] Domestic travel faces minimal record-based hurdles beyond probation conditions, though enhanced screening applies at airports for those on watchlists tied to convictions.[140]Individual and Societal Impacts

Barriers for Ex-Offenders and Employment Outcomes

Ex-offenders encounter substantial employment barriers stemming from criminal records, which employers view as indicators of potential recidivism and liability risks. Audit studies demonstrate that applicants disclosing criminal histories receive 50% fewer callbacks compared to those without records, with the disparity persisting across industries and even for minor offenses.[141] This reluctance is grounded in empirical recidivism data, where approximately 68% of released prisoners are rearrested within three years, prompting rational employer caution to mitigate workplace risks such as theft or violence.[142] Unemployment rates among formerly incarcerated individuals remain elevated, often exceeding 27% for those aged 25-44, compared to the national average of around 4% in recent years; in specific cohorts like Illinois releases, post-incarceration unemployment reaches 46%.[143][144] Individuals with felony records are four to six times more likely to be unemployed than those without, a gap attributable not solely to incarceration effects but to the signaling value of records in hiring decisions.[145] Legal restrictions further compound this, barring ex-felons from fields like education, healthcare, and finance in many jurisdictions, limiting access to stable, higher-wage jobs.[146] Policies such as "ban-the-box" laws, which delay criminal history inquiries, have yielded mixed outcomes; while intended to reduce initial barriers, they can foster statistical discrimination, particularly against racial minorities perceived as higher-risk, without substantially boosting overall hiring of ex-offenders.[147] Employers' fears of negligent hiring lawsuits amplify hesitation, as records heighten perceived accountability for employee misconduct, despite limited evidence that hiring vetted ex-offenders increases firm-level risks when recidivism predictors like offense severity are considered.[148] These dynamics result in ex-offenders often relegated to low-wage, unstable "McJobs," perpetuating cycles of poverty and hindering long-term reintegration.[149]Effects on Recidivism and Public Safety

Empirical research indicates that visible criminal records often exacerbate recidivism by imposing barriers to employment and social reintegration, which are established protective factors against reoffending. Stable employment post-incarceration reduces the likelihood of rearrest and reincarceration, yet background checks revealing criminal histories frequently result in hiring denials, even for non-violent or dated offenses. A study of Michigan's expungement process found that sealing eligible convictions led to a 13% increase in employment odds and a 23% rise in quarterly wages (approximately $1,111) within one year, with no corresponding uptick in recidivism; in fact, expunged individuals exhibited rearrest rates of 7.1% over five years, lower than comparable non-expunged cohorts and the general population.[150] Similarly, perceived stigma from criminal labels correlates with anticipated future discrimination, indirectly undermining community adjustment and heightening reoffending risk through diminished economic stability, though direct links to recidivism vary by demographics such as race.[151] Policies limiting employer access to criminal records provide causal evidence of this dynamic. Massachusetts' 2010–2012 "ban the box" reform, which delayed initial disclosure of histories, decreased recidivism probability by 5.2 percentage points among ex-offenders, even after controlling for age, offense type, and economic conditions, suggesting that reduced visibility facilitates job attainment and thereby curbs reoffending.[152] Provisional employment clearances in high-risk sectors, such as New York healthcare, yielded a 4.2% drop in rearrests within three years for screened workers, underscoring how overcoming record-based barriers can enhance desistance without compromising oversight.[153] These findings align with redemption research showing that reoffending risk declines sharply with crime-free time—often reaching negligible levels after 7–10 years for many offenders—implying that perpetual record visibility inefficiently perpetuates marginalization for low-risk individuals.[153] Regarding public safety, while unrestricted access to records via background checks mitigates risks of negligent hiring in sensitive roles (e.g., childcare or finance), broad application may net harm by elevating recidivism through systemic exclusion. Inaccurate or outdated records—such as unresolved arrests—further distort assessments, potentially disqualifying reformed individuals while failing to flag persistent threats.[153] Reforms like targeted expungement for minor offenses preserve accountability for serious or recent crimes, as evidenced by sustained low violent recidivism (0.6% reconviction rate over five years) among Michigan expungement recipients, who remained 99.4% free of violent convictions.[150] Thus, calibrated record management—balancing deterrence for high-risk cases with relief for others—appears to optimize safety by promoting reintegration over indefinite stigmatization.[152][153]Economic and Social Analyses

Criminal records impose substantial economic burdens on individuals and society, primarily through diminished employment prospects and associated lost productivity. Empirical field experiments demonstrate that applicants with criminal records receive approximately 60% fewer callbacks from employers compared to otherwise identical candidates without records, even for minor offenses unrelated to the job.[141] This discrimination persists across industries and is driven by employers' rational assessments of recidivism risk, as individuals with records exhibit higher reoffending rates—estimated at 67% within three years post-release in U.S. federal data—potentially leading to workplace liabilities.[153] Over lifetimes, such barriers translate to forgone earnings exceeding $500,000 per affected individual, with aggregate U.S. losses from incarceration-related records reaching hundreds of billions annually when factoring in reduced tax revenues and increased welfare dependency.[154] Societally, these economic effects compound through elevated recidivism and public safety costs, as unemployment correlates with a 20-30% higher likelihood of reoffending due to financial desperation rather than inherent stigma alone.[153] Analyses of background check policies indicate that access to records enables employers to mitigate hiring risks, potentially lowering overall crime rates by allocating jobs to lower-risk candidates; jurisdictions restricting such access have observed no net employment gains for ex-offenders but increased recidivism in some cohorts.[145] Cost-benefit evaluations of record persistence versus expungement reveal mixed outcomes: while targeted expungements for low-risk individuals may yield modest employment boosts in gig economies, broad sealing shows negligible average improvements in labor market trajectories and can impose administrative costs on courts exceeding $100 million yearly in large states, without commensurate reductions in reoffense rates.[155][156] Socially, criminal records engender stigma that exacerbates family disruption and intergenerational poverty, with children of recorded parents facing 2-3 times higher odds of juvenile delinquency due to modeled behaviors and economic instability rather than mere labeling effects.[64] This causal chain—rooted in disrupted human capital from prior offenses—undermines community cohesion, as ex-offenders' exclusion from stable housing and social networks perpetuates cycles of isolation; surveys of reintegration programs highlight that persistent records signal unremedied risk, justifying employer and landlord caution amid evidence of non-compliance in up to 40% of parolees.[151] Critiques from advocacy sources often overstate discriminatory intent, ignoring first-principles employer incentives to prioritize verifiable safety over unproven rehabilitation claims, though empirical data affirm that records' transparency correlates with lower societal victimization costs by informing allocative decisions in labor and housing markets.[157][158]Expungement, Sealing, and Record Relief

Mechanisms and Eligibility Criteria

Expungement refers to the legal process by which arrests, charges, or convictions are removed from public criminal records, effectively treating them as if they never occurred, though records may persist in limited government databases for law enforcement purposes.[159] This mechanism typically requires filing a petition with the court where the case originated, providing evidence of eligibility, and obtaining judicial approval after a hearing, during which prosecutors may object based on public safety concerns.[160] In some jurisdictions, automatic expungement applies to non-conviction records or low-level offenses after a statutory waiting period without further legal action required from the individual.[161] Sealing, distinct from expungement, restricts public access to records while preserving them for use by courts, law enforcement, and certain licensing agencies, meaning the conviction is not erased but concealed from general background checks.[162] The process mirrors petition-based expungement, involving a court filing, verification of qualifications, and an order directing agencies to limit disclosure, though digital footprints in private or federal systems often remain accessible.[163] Other record relief options include set-asides, which vacate the conviction judgment while noting the original plea or finding, and nondisclosure orders, which seal records from employers but allow government access, as implemented in states like Texas for eligible deferred adjudications.[164] Eligibility for these mechanisms generally hinges on completion of all sentence terms, including probation and restitution, followed by a crime-free waiting period ranging from three to ten years depending on the jurisdiction and offense severity.[165] Qualifying offenses are typically limited to misdemeanors or non-violent felonies, excluding serious crimes such as murder, sexual assault, or offenses involving minors, with 38 U.S. states and the District of Columbia permitting relief for at least some felony convictions as of March 2024.[166] Applicants must demonstrate rehabilitation through lack of subsequent arrests, stable employment, or community ties, though federal convictions face stricter barriers, with no routine expungement available for adult felonies and relief confined to pardons or juvenile records.[167] Discretionary denials occur if the offense poses ongoing risks, underscoring that relief is not guaranteed even for eligible cases.[163]Recent Legislative Trends (2020s Clean Slate Laws)

In the 2020s, a growing number of U.S. states enacted Clean Slate laws establishing automated processes for sealing or expunging eligible criminal records, primarily for non-violent misdemeanors and select felonies, after specified periods of offense-free behavior typically ranging from three to eight years.[168] These laws aim to alleviate barriers to employment and reintegration by limiting public access to records without requiring individual petitions, building on Pennsylvania's pioneering 2018 legislation.[169] By mid-2025, at least 12 states plus Washington, D.C., had implemented such automated mechanisms, with bipartisan support evident in passages across red, blue, and purple jurisdictions.[169] Eligibility often excludes serious violent offenses, sex crimes, and recent convictions, though implementation varies in scope and timelines.[170] Key enactments in the decade include Michigan's Clean Slate law, signed on October 13, 2020, and effective April 11, 2021, which automates the set-aside of certain misdemeanors after five years and eligible felonies after seven years of good conduct.[171] Connecticut followed in June 2021 with a law effective January 1, 2023, automatically erasing records of most misdemeanors after seven years and certain Class D felonies after eight years.[161] Other states passing similar measures include Utah (2020), New Jersey, New York, and Virginia, with Virginia expanding automatic sealing for select misdemeanors effective July 1, 2025.[168][172] Maryland's Expungement Reform Act of 2025, passed in May and initiating processes from October 1, 2025, automates misdemeanor sealing after seven years while broadening eligibility by not disqualifying individuals solely for probation violations.[173][174]| State | Enactment Year | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Michigan | 2020 | Automates misdemeanors after 5 years, felonies after 7 years; excludes violent crimes.[171] |

| Connecticut | 2021 | Misdemeanors after 7 years, select felonies after 8 years; effective 2023.[161] |

| Virginia | 2025 expansion | Automatic sealing for misdemeanors like petit larceny; effective July 1, 2025.[172] |

| Maryland | 2025 | Misdemeanor automation after 7 years; clarifies probation non-disqualification.[173] |