Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alameda County, California

View on Wikipedia

Alameda County (/ˌæləˈmiːdə/ ⓘ AL-ə-MEE-də) is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,682,353,[4][6] making it the 7th-most populous county in the state[7] and 21st most populous nationally. The county seat is Oakland.[8] Alameda County is in the San Francisco Bay Area, occupying much of the East Bay region.

Key Information

The Spanish word alameda means either "a grove of poplars...or a tree lined street". The name was originally used to describe the Arroyo de la Alameda; the willow and sycamore trees along the banks of the river reminded the early Spanish explorers of a road lined with trees.[9][10]

Alameda County is part of the San Francisco–Oakland–Berkeley, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area, and the San Jose–San Francisco–Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area.

History

[edit]The county was formed on March 25, 1853, from a large portion of Contra Costa County and a smaller portion of Santa Clara County.

The county seat at the time of the county's formation was located at Alvarado, now part of Union City. In 1856, it was moved to San Leandro, where the county courthouse was destroyed by the devastating 1868 quake on the Hayward Fault. The county seat was then re-established in the town of Brooklyn from 1872 to 1875. Brooklyn is now part of Oakland, which has been the county seat since 1873.

Much of what is now an intensively urban region was initially developed as a trolley car suburb of San Francisco in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Key System moved commuters to and from the Key System Mole, where ferries bridged the gap across San Francisco Bay.

The historical progression from Native American tribal lands to Spanish then Mexican ranches, then to farms, ranches, and orchards, then to multiple city centers and suburbs, is shared with the adjacent and closely associated Contra Costa County.

Law, government and politics

[edit]

Government

[edit]The Government of Alameda County is defined and authorized under the California Constitution, California law, and the Charter of the County of Alameda.[11] Much of the Government of California is in practice the responsibility of county governments such as the Government of Alameda County, while municipalities such as the City of Oakland and the City of Berkeley provide additional, often non-essential services. The County government provides countywide services such as elections and voter registration, law enforcement, jails, vital records, property records, tax collection, and public health. In addition it is the local government for all unincorporated areas, and provides services such as law enforcement to some incorporated cities under a contract arrangement.

It is composed of the elected five-member Alameda County Board of Supervisors (BOS) as the county legislature, several other elected offices and officers including the Sheriff, the District Attorney, Assessor, Auditor-Controller/County Clerk/Recorder, Treasurer/Tax Collector, and numerous county departments and entities under the supervision of the County Administrator. In addition, several entities of the government of California have jurisdiction conterminous with Alameda County, such as the Alameda County Superior Court.

The current supervisors are:[12]

- David Haubert, district 1,

- Elisa Márquez, district 2,

- Lena Tam, district 3,

- Nate Miley, district 4, and

- Keith Carson, district 5.

The Board elects a president who presides at all meetings of the Board and appoints committees to handle work involving the major programs of the county. If the president is absent for a meeting, the vice president shall be responsible. A Board election occurs every two years for these positions. Supervisor Carson is serving currently as president; Supervisor Miley is vice president.

The county's law enforcement is overseen by an elected Sheriff/Coroner and an elected District Attorney. The Sheriff supervises the deputies of the Alameda County Sheriff's Office, whose primary responsibilities include policing unincorporated areas of the county and cities within the county which contract with the Sheriff's Office for police services; providing security and law enforcement for county buildings including courthouses, the county jail and other county properties; providing support resources, such as a forensics laboratory and search and rescue capabilities, to other law enforcement agencies throughout the county; and serving the process of the county's Superior Court system. The District Attorney's office is responsible for prosecuting all criminal violations of the laws of the state of California, the county, or its constituent municipalities, in the Alameda County Superior Court. The current Sheriff is Yesenia Sanchez, who was elected in 2022, succeeding Greg Ahern, who had served in the post for 16 years. The Sheriff's Office operates two jails: Santa Rita Jail in Dublin, and Glenn E. Dyer Detention Facility in downtown Oakland.

In 2009, Nancy E. O'Malley was appointed Alameda County district attorney after Tom Orloff retired. She served two terms and did not run for reelection in 2022.[13] Pamela Price was elected as district attorney in 2022.[14]

The Alameda County Fire Department (ACFD)[15] was formed on July 1, 1993, as a dependent district, with the Board of Supervisors as its governing body. Municipal and specialized fire departments have been consolidated into the ACFD over the years. 1993 brought in the Castro Valley and Eden Consolidated FD, and the County Fire Patrol. San Leandro joined in 1995, Dublin in 1997, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 2002, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 2007, The Alameda County Regional Emergency Communications Center in 2008, and Newark and Union City in 2010. Emeryville joined the ACFD in 2012.

The Alameda County Water District is a special district within Alameda County created to distribute water, but it is not operated by Alameda County administrators. It is operated by an elected board of directors.

Alameda County Superior Court operates in twelve separate locations throughout the county, with its central René C. Davidson Courthouse located in Oakland near Lake Merritt. Most major criminal trials and complex civil cases are heard at this location or in courtrooms within the County Administration Building across the street.

State and federal representation

[edit]In the California State Assembly, Alameda County is split between five districts:

- the 14th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Buffy Wicks

- the 16th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Rebecca Bauer-Kahan

- the 18th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Mia Bonta

- the 20th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Liz Ortega

- the 24th Assembly district, represented by Democrat Alex Lee[16]

In the California State Senate, the county is split between four districts:

- the 5th senatorial district, represented by Democrat Jerry McNerney

- the 7th senatorial district, represented by Democrat Jesse Arreguín

- the 9th senatorial district, represented by Democrat Tim Grayson

- the 10th senatorial district, represented by Democrat Aisha Wahab[17]

In the United States House of Representatives, the county is split between four districts:

- California's 10th congressional district, represented by Democrat Mark DeSaulnier

- California's 12th congressional district, represented by Democrat Lateefah Simon

- California's 14th congressional district, represented by Democrat Eric Swalwell

- California's 17th congressional district, represented by Democrat Ro Khanna

Politics

[edit]Since 1932, Alameda County has been a stronghold of the Democratic Party, with Dwight Eisenhower being the only Republican presidential nominee to have carried the county since. Prior to 1932, the county had been a Republican stronghold. Piedmont resident William F. Knowland was the Republican U.S. Senate Leader from 1953 to 1959. Even when Ronald Reagan won the national popular vote by an 18.3% margin in 1984, Walter Mondale won Alameda County by a larger margin. In 2004 it voted for John Kerry, who won over 75% of the vote. Every city and town voted Democratic.[18] George H.W. Bush in 1988 was the last Republican to break 30% of the county's vote and Ronald Reagan in 1984 was the last to break 40% of the vote (carrying 40.01%).[19]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 140,789 | 21.02% | 499,551 | 74.57% | 29,567 | 4.41% |

| 2020 | 136,309 | 17.62% | 617,659 | 79.83% | 19,785 | 2.56% |

| 2016 | 95,922 | 14.54% | 514,842 | 78.06% | 48,779 | 7.40% |

| 2012 | 108,182 | 18.12% | 469,684 | 78.69% | 19,027 | 3.19% |

| 2008 | 119,555 | 19.19% | 489,106 | 78.52% | 14,252 | 2.29% |

| 2004 | 130,911 | 23.29% | 422,585 | 75.18% | 8,594 | 1.53% |

| 2000 | 119,279 | 24.13% | 342,889 | 69.36% | 32,168 | 6.51% |

| 1996 | 106,581 | 23.07% | 303,903 | 65.77% | 51,560 | 11.16% |

| 1992 | 109,292 | 20.62% | 334,224 | 63.04% | 86,629 | 16.34% |

| 1988 | 162,815 | 33.99% | 310,283 | 64.78% | 5,899 | 1.23% |

| 1984 | 192,408 | 40.01% | 282,041 | 58.65% | 6,425 | 1.34% |

| 1980 | 158,531 | 37.96% | 201,720 | 48.30% | 57,366 | 13.74% |

| 1976 | 155,280 | 38.09% | 235,988 | 57.89% | 16,413 | 4.03% |

| 1972 | 201,862 | 42.84% | 259,254 | 55.02% | 10,079 | 2.14% |

| 1968 | 153,285 | 37.63% | 219,545 | 53.90% | 34,519 | 8.47% |

| 1964 | 142,998 | 33.46% | 283,833 | 66.42% | 509 | 0.12% |

| 1960 | 183,354 | 45.61% | 217,172 | 54.02% | 1,474 | 0.37% |

| 1956 | 192,911 | 52.40% | 174,033 | 47.27% | 1,187 | 0.32% |

| 1952 | 201,976 | 52.69% | 178,239 | 46.50% | 3,079 | 0.80% |

| 1948 | 150,588 | 46.57% | 154,549 | 47.80% | 18,194 | 5.63% |

| 1944 | 122,982 | 41.83% | 169,631 | 57.70% | 1,374 | 0.47% |

| 1940 | 116,961 | 43.56% | 148,224 | 55.21% | 3,311 | 1.23% |

| 1936 | 82,352 | 35.09% | 149,323 | 63.63% | 3,011 | 1.28% |

| 1932 | 89,303 | 43.68% | 106,388 | 52.04% | 8,761 | 4.29% |

| 1928 | 118,539 | 65.42% | 60,875 | 33.60% | 1,780 | 0.98% |

| 1924 | 81,454 | 61.48% | 8,020 | 6.05% | 43,016 | 32.47% |

| 1920 | 73,177 | 69.11% | 21,468 | 20.27% | 11,244 | 10.62% |

| 1916 | 51,417 | 50.34% | 43,748 | 42.84% | 6,966 | 6.82% |

| 1912 | 0 | 0.00% | 24,418 | 36.75% | 42,034 | 63.25% |

| 1908 | 21,380 | 64.24% | 7,110 | 21.36% | 4,793 | 14.40% |

| 1904 | 19,065 | 70.32% | 4,399 | 16.23% | 3,646 | 13.45% |

| 1900 | 14,324 | 64.64% | 6,677 | 30.13% | 1,158 | 5.23% |

| 1896 | 13,429 | 60.43% | 8,394 | 37.77% | 400 | 1.80% |

| 1892 | 8,792 | 47.60% | 7,114 | 38.52% | 2,564 | 13.88% |

| 1888 | 8,840 | 57.18% | 5,693 | 36.82% | 928 | 6.00% |

| 1884 | 7,471 | 60.26% | 4,734 | 38.18% | 193 | 1.56% |

| 1880 | 5,899 | 59.65% | 3,894 | 39.38% | 96 | 0.97% |

On November 4, 2008, Alameda County voted 61.92% against Proposition 8, which won statewide, and which amended the California Constitution to ban same-sex marriage. The county garnered the sixth highest "no" vote, by percentage, of all California counties, and was the second largest county, by total voter turnout, to vote against it.[20]

Voter registration statistics as of October 24, 2022

[edit]| Population and registered voters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total eligible population[21] | 1,140,774 | |

| Registered voters[21][note 1] | 931,130 | 81.6% |

| Democratic[21] | 562,093 | 60.4% |

| Republican[21] | 100,977 | 10.8% |

| Democratic–Republican spread[21] | +461,116 | +49.6% |

| American Independent[21] | 21,621 | 2.3% |

| Libertarian[21] | 6,351 | 0.6% |

| Green[21] | 5,628 | 0.6% |

| Peace and Freedom[21] | 4,340 | 0.4% |

| Unknown[21] | 26 | 0.0% |

| Other[21] | 5,686 | 0.6% |

| No party preference[21] | 224,408 | 24.1% |

Cities by population and voter registration

[edit]| Cities by population and voter registration as of 2013 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[22] | Registered voters[23] [note 1] |

Democratic[23] | Republican[23] | D–R spread[23] | Other[23] | No party preference[23] |

| Alameda | 73,239 | 59.7% | 55.0% | 14.2% | +40.8% | 10.0% | 20.8% |

| Albany | 18,217 | 59.1% | 64.0% | 6.5% | +57.5% | 11.8% | 18.9% |

| Berkeley | 111,008 | 72.9% | 64.7% | 4.4% | +60.3% | 15.3% | 17.0% |

| Dublin | 44,171 | 52.7% | 42.7% | 24.6% | +18.1% | 14.3% | 21.3% |

| Emeryville | 9,698 | 64.7% | 59.6% | 7.6% | +52.0% | 15.3% | 19.5% |

| Fremont | 211,748 | 47.9% | 46.4% | 17.5% | +28.9% | 12.2% | 26.0% |

| Hayward | 142,936 | 43.7% | 60.1% | 12.7% | +47.4% | 11.0% | 18.4% |

| Livermore | 79,710 | 61.5% | 39.4% | 33.1% | +6.3% | 12.4% | 18.2% |

| Newark | 42,322 | 48.6% | 53.9% | 16.6% | +37.3% | 10.7% | 21.1% |

| Oakland | 389,397 | 55.4% | 66.7% | 5.9% | +60.8% | 12.1% | 16.9% |

| Piedmont | 10,640 | 79.7% | 56.0% | 19.6% | +36.4% | 8.4% | 17.9% |

| Pleasanton | 69,220 | 61.5% | 38.2% | 31.8% | +6.4% | 12.0% | 20.5% |

| San Leandro | 83,877 | 50.9% | 58.7% | 13.7% | +45.0% | 10.2% | 19.5% |

| Union City | 68,830 | 48.6% | 54.9% | 13.1% | +41.8% | 10.5% | 23.3% |

Geography and climate

[edit]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 821 square miles (2,130 km2), of which 739 square miles (1,910 km2) is land and 82 square miles (210 km2) (10%) is water.[24] The San Francisco Bay borders the county on the west.

The crest of the Berkeley Hills forms part of the northeastern boundary and reaches into the center of the county. A coastal plain several miles wide lines the bay; and is Oakland's most populous region. Livermore Valley lies in the eastern part of the county. Amador Valley abuts the western edge of Livermore Valley and continues west to the Pleasanton Ridge. The ridges and valleys of the Diablo Range, containing the county's highest peaks, cover the very sparsely populated southeast portion of the county.

The Hayward Fault, a major branch of the San Andreas Fault to the west, runs through the most populated parts of Alameda County, while the Calaveras Fault runs through the southeastern part of the county.

The areas near the Bay itself have a maritime warm-summer Mediterranean climate, whereas behind the mountains, summers are significantly warmer. The climate charts below are for Oakland and inland Livermore.

| Climate data for Oakland Museum (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1970–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

82 (28) |

88 (31) |

97 (36) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

99 (37) |

109 (43) |

103 (39) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 67.0 (19.4) |

72.4 (22.4) |

75.9 (24.4) |

82.8 (28.2) |

85.5 (29.7) |

89.1 (31.7) |

87.3 (30.7) |

88.7 (31.5) |

89.7 (32.1) |

87.8 (31.0) |

75.8 (24.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

94.7 (34.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.0 (14.4) |

61.8 (16.6) |

63.6 (17.6) |

66.0 (18.9) |

68.8 (20.4) |

71.2 (21.8) |

71.7 (22.1) |

73.0 (22.8) |

74.1 (23.4) |

71.7 (22.1) |

64.6 (18.1) |

58.1 (14.5) |

66.6 (19.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.4 (10.8) |

54.7 (12.6) |

56.4 (13.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

61.1 (16.2) |

63.5 (17.5) |

64.3 (17.9) |

65.6 (18.7) |

66.0 (18.9) |

63.3 (17.4) |

57.1 (13.9) |

51.8 (11.0) |

59.2 (15.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 44.7 (7.1) |

47.7 (8.7) |

49.1 (9.5) |

50.5 (10.3) |

53.5 (11.9) |

55.7 (13.2) |

56.9 (13.8) |

58.1 (14.5) |

57.8 (14.3) |

55.1 (12.8) |

49.8 (9.9) |

45.4 (7.4) |

51.9 (11.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 38.0 (3.3) |

40.0 (4.4) |

42.2 (5.7) |

45.2 (7.3) |

49.1 (9.5) |

51.9 (11.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

55.5 (13.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

49.0 (9.4) |

41.6 (5.3) |

37.3 (2.9) |

36.0 (2.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 30 (−1) |

29 (−2) |

34 (1) |

37 (3) |

43 (6) |

48 (9) |

51 (11) |

50 (10) |

48 (9) |

43 (6) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

26 (−3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.59 (117) |

4.65 (118) |

3.52 (89) |

1.32 (34) |

0.73 (19) |

0.12 (3.0) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.23 (5.8) |

1.29 (33) |

3.07 (78) |

4.44 (113) |

24.09 (612) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in.) | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 8.1 | 10.4 | 69.1 |

| Source: NOAA[25][26] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Livermore, California (1903–2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

80 (27) |

88 (31) |

96 (36) |

108 (42) |

113 (45) |

113 (45) |

112 (44) |

115 (46) |

106 (41) |

93 (34) |

79 (26) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.9 (19.4) |

71.4 (21.9) |

77.9 (25.5) |

85.8 (29.9) |

94.3 (34.6) |

102.0 (38.9) |

104.3 (40.2) |

102.8 (39.3) |

101.2 (38.4) |

92.6 (33.7) |

79.0 (26.1) |

67.8 (19.9) |

106.3 (41.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 56.8 (13.8) |

61.2 (16.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

70.5 (21.4) |

76.4 (24.7) |

83.1 (28.4) |

89.0 (31.7) |

88.2 (31.2) |

86.0 (30.0) |

77.7 (25.4) |

66.3 (19.1) |

57.5 (14.2) |

73.2 (22.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 36.7 (2.6) |

39.4 (4.1) |

41.3 (5.2) |

43.6 (6.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

51.7 (10.9) |

54.2 (12.3) |

54.0 (12.2) |

52.5 (11.4) |

47.7 (8.7) |

41.1 (5.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

45.6 (7.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 26.4 (−3.1) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

32.1 (0.1) |

34.9 (1.6) |

39.3 (4.1) |

44.4 (6.9) |

47.7 (8.7) |

47.8 (8.8) |

44.5 (6.9) |

38.3 (3.5) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

21 (−6) |

22 (−6) |

29 (−2) |

32 (0) |

38 (3) |

36 (2) |

36 (2) |

35 (2) |

29 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

18 (−8) |

18 (−8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.97 (75) |

2.47 (63) |

2.15 (55) |

1.00 (25) |

.44 (11) |

.11 (2.8) |

.02 (0.51) |

.04 (1.0) |

.22 (5.6) |

.67 (17) |

1.54 (39) |

2.56 (65) |

14.19 (359.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ .01 in) | 10 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 58 |

| Average snowy days | trace | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Source: WRCC[27] and pogodaiklimat.ru[28] | |||||||||||||

Adjacent counties

[edit]The City and County of San Francisco, California, borders the county on the west, and has a small land border with the city of Alameda, California due to land filling.[29]

Santa Clara County borders the county on the south.

San Joaquin County borders the county on the east.

Contra Costa County borders the county on the north.

Stanislaus County borders the county on the easternmost end of its southern boundary for 250 feet (76 m).[30]

National protected area

[edit]Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 8,927 | — | |

| 1870 | 24,237 | 171.5% | |

| 1880 | 62,976 | 159.8% | |

| 1890 | 93,864 | 49.0% | |

| 1900 | 130,197 | 38.7% | |

| 1910 | 246,131 | 89.0% | |

| 1920 | 344,177 | 39.8% | |

| 1930 | 474,883 | 38.0% | |

| 1940 | 513,011 | 8.0% | |

| 1950 | 740,315 | 44.3% | |

| 1960 | 908,209 | 22.7% | |

| 1970 | 1,073,184 | 18.2% | |

| 1980 | 1,105,379 | 3.0% | |

| 1990 | 1,279,182 | 15.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,443,741 | 12.9% | |

| 2010 | 1,510,271 | 4.6% | |

| 2020 | 1,682,353 | 11.4% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 1,649,060 | [31] | −2.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[32] 1790–1960[33] 1900–1990[34] 1990–2000[35] 2010[36] 2020[37] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1980[38] | Pop 1990[39] | Pop 2000[40] | Pop 2010[36] | Pop 2020[37] | % 1980 | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 675,338 | 680,017 | 591,095 | 514,559 | 472,277 | 61.10% | 53.16% | 40.94% | 34.07% | 28.07% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 200,950 | 222,873 | 211,124 | 184,126 | 159,499 | 18.18% | 17.42% | 14.62% | 12.19% | 9.48% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 7,446 | 6,763 | 5,306 | 4,189 | 4,131 | 0.67% | 0.53% | 0.37% | 0.28% | 0.25% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 85,899 | 184,813 | 292,673 | 390,524 | 540,511 | 7.77% | 14.45% | 20.27% | 25.86% | 32.13% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone (NH) | x | x | 8,458 | 11,931 | 13,209 | x | x | 0.59% | 0.79% | 0.79% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 5,784 | 2,911 | 4,676 | 4,191 | 10,440 | 0.52% | 0.23% | 0.32% | 0.28% | 0.62% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | x | x | 56,499 | 60,862 | 88,537 | x | x | 3.91% | 4.03% | 5.26% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 129,962 | 181,805 | 273,910 | 339,889 | 393,749 | 11.76% | 14.21% | 18.97% | 22.51% | 23.40% |

| Total | 1,105,379 | 1,279,182 | 1,443,741 | 1,510,271 | 1,682,353 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2014

[edit]

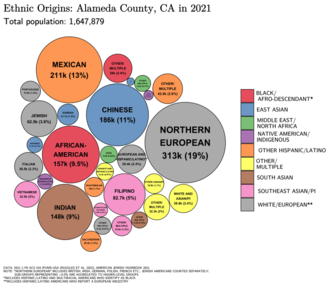

A 2014 analysis by The Atlantic found Alameda County to be the fourth most racially diverse county in the United States, in terms of closest to equal representation of each racial and ethnic group,—behind Aleutians West Census Area and Aleutians East Borough in Alaska, and Queens County in New York—as well as the most diverse county in California.[41] The 2020 census shows Alameda as having one of the highest Asian percentages and being one of two counties in the continental US, along with neighboring Santa Clara County, California, to have an Asian plurality - consisting largely of Chinese, Indian and Filipino ancestry.[42]

2011

[edit]| Population, race, and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population[22] | 1,494,876 | ||||

| White[22] | 690,261 | 46.2% | |||

| Asian[22] | 391,627 | 26.2% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[43] | 332,103 | 22.2% | |||

| Black or African American[22] | 186,326 | 12.5% | |||

| Some other race[22] | 131,958 | 8.8% | |||

| Two or more races[22] | 75,411 | 5.0% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander[22] | 12,191 | 0.8% | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native[22] | 7,102 | 0.5% | |||

| Per capita income[44] | $34,937 | ||||

| Median household income[45] | $70,821 | ||||

| Median family income[46] | $87,012 | ||||

Places by population, race, and income

[edit]| Places by population and race | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[47] | Population[22] | White[22] | Other[22] [note 2] |

Asian[22] | Black or African American[22] |

Native American[22] [note 3] |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[43] |

| Alameda | City | 73,239 | 49.5% | 9.8% | 33.1% | 6.7% | 0.9% | 11.8% |

| Albany | City | 18,217 | 60.7% | 7.0% | 29.1% | 3.0% | 0.1% | 9.7% |

| Ashland | CDP | 22,106 | 53.4% | 11.9% | 16.4% | 17.0% | 1.3% | 46.7% |

| Berkeley | City | 111,008 | 61.5% | 8.0% | 20.6% | 9.3% | 0.6% | 10.5% |

| Castro Valley | CDP | 60,882 | 62.9% | 7.9% | 21.7% | 6.8% | 0.8% | 17.4% |

| Cherryland | CDP | 14,394 | 46.8% | 31.1% | 9.0% | 8.6% | 4.5% | 55.9% |

| Dublin | City | 44,171 | 57.5% | 8.7% | 26.2% | 6.9% | 0.7% | 12.9% |

| Emeryville | City | 9,698 | 44.1% | 5.7% | 36.3% | 13.8% | 0.2% | 8.8% |

| Fairview | CDP | 9,597 | 49.2% | 13.5% | 18.1% | 17.7% | 1.5% | 18.5% |

| Fremont | City | 211,748 | 33.9% | 12.8% | 49.0% | 3.3% | 1.1% | 15.4% |

| Hayward | City | 142,936 | 36.9% | 24.9% | 23.6% | 11.4% | 3.2% | 39.9% |

| Livermore | City | 79,710 | 78.9% | 8.4% | 10.3% | 1.8% | 0.5% | 19.0% |

| Newark | City | 42,322 | 42.1% | 24.4% | 26.2% | 4.3% | 3.0% | 35.2% |

| Oakland | City | 389,397 | 39.0% | 15.7% | 16.1% | 28.1% | 1.1% | 25.0% |

| Piedmont | City | 10,640 | 76.1% | 3.4% | 19.5% | 0.9% | 0.1% | 3.9% |

| Pleasanton | City | 69,220 | 68.0% | 6.2% | 22.9% | 2.5% | 0.4% | 10.6% |

| San Leandro | City | 83,877 | 44.9% | 10.2% | 29.6% | 13.4% | 1.9% | 26.0% |

| San Lorenzo | CDP | 24,096 | 54.1% | 17.2% | 20.8% | 6.5% | 1.4% | 35.9% |

| Sunol | CDP | 760 | 84.3% | 11.6% | 4.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 15.8% |

| Union City | City | 68,830 | 21.5% | 17.8% | 53.3% | 6.2% | 1.2% | 21.5% |

| Places by population and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[47] | Population[48] | Per capita income[44] | Median household income[45] | Median family income[46] |

| Alameda | City | 73,239 | $39,160 | $75,832 | $93,349 |

| Albany | City | 18,217 | $37,552 | $72,479 | $87,500 |

| Ashland | CDP | 22,106 | $20,357 | $48,026 | $53,038 |

| Berkeley | City | 111,008 | $38,896 | $60,908 | $102,976 |

| Castro Valley | CDP | 60,882 | $38,535 | $82,370 | $97,628 |

| Cherryland | CDP | 14,394 | $19,610 | $50,987 | $48,120 |

| Dublin | City | 44,171 | $41,197 | $111,481 | $121,380 |

| Emeryville | City | 9,698 | $52,258 | $69,274 | $99,954 |

| Fairview | CDP | 9,597 | $38,267 | $85,288 | $97,969 |

| Fremont | City | 211,748 | $38,752 | $98,513 | $109,853 |

| Hayward | City | 142,936 | $24,987 | $62,115 | $69,044 |

| Livermore | City | 79,710 | $41,741 | $96,322 | $108,406 |

| Newark | City | 42,322 | $29,375 | $81,777 | $84,244 |

| Oakland | City | 389,397 | $31,675 | $51,144 | $58,237 |

| Piedmont | City | 10,640 | $92,232 | $199,304 | $221,875 |

| Pleasanton | City | 69,220 | $50,745 | $118,713 | $136,464 |

| San Leandro | City | 83,877 | $27,878 | $61,857 | $72,080 |

| San Lorenzo | CDP | 24,096 | $25,553 | $73,053 | $76,365 |

| Sunol | CDP | 760 | $62,651 | $72,656 | $86,250 |

| Union City | City | 68,830 | $29,612 | $82,634 | $91,176 |

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States census reported that Alameda County had a population of 1,510,271. The population density was 2,047.6 inhabitants per square mile (790.6/km2). The racial makeup of Alameda County was 649,122 (43.0%) White, 190,451 (12.6%) African American, 9,799 (0.6%) Native American, 394,560 (26.1%) Asian (9.7% Chinese, 5.5% Filipino, 4.8% Indian, 2.0% Vietnamese, 1.2% Korean, 0.8% Japanese, 2.2% Other Asian), 12,802 (0.8%) Pacific Islander, 162,540 (10.8%) from other races, and 90,997 (6.0%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 339,889 persons (22.5%): 16.4% Mexican, 0.8% Puerto Rican, 0.2% Cuban, 5.1% Other Hispanic.[49]

|

| Population reported at 2010 United States census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The County | Total Population |

White | African American |

Native American |

Asian | Pacific Islander |

other races |

two or more races |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| Alameda County | 1,510,271 | 649,122 | 190,451 | 9,799 | 394,560 | 12,802 | 162,540 | 90,997 | 339,889 |

| Incorporated cities |

Total Population |

White | African American |

Native American |

Asian | Pacific Islander |

other races |

two or more races |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| Alameda | 73,812 | 37,460 | 4,759 | 426 | 23,058 | 381 | 2,463 | 5,265 | 8,092 |

| Albany | 18,539 | 10,128 | 645 | 88 | 5,790 | 37 | 607 | 1,244 | 1,891 |

| Berkeley | 112,580 | 66,996 | 11,241 | 479 | 21,690 | 186 | 4,994 | 6,994 | 12,209 |

| Dublin | 46,036 | 23,634 | 4,347 | 246 | 12,321 | 287 | 2,458 | 2,743 | 6,663 |

| Emeryville | 10,080 | 4,490 | 1,764 | 44 | 2,775 | 16 | 348 | 643 | 927 |

| Fremont | 214,089 | 70,320 | 7,103 | 976 | 108,332 | 1,169 | 13,605 | 12,584 | 31,698 |

| Hayward | 144,186 | 49,309 | 17,099 | 1,396 | 31,666 | 4,535 | 30,004 | 10,177 | 58,730 |

| Livermore | 80,968 | 60,418 | 1,702 | 476 | 6,802 | 277 | 6,960 | 4,333 | 16,920 |

| Newark | 42,573 | 17,566 | 2,002 | 279 | 11,571 | 621 | 7,735 | 2,799 | 14,994 |

| Oakland | 390,724 | 134,925 | 109,471 | 3,040 | 65,811 | 2,222 | 53,378 | 21,877 | 99,068 |

| Piedmont | 10,667 | 7,917 | 144 | 6 | 1,939 | 13 | 94 | 554 | 421 |

| Pleasanton | 70,285 | 47,058 | 1,190 | 226 | 16,322 | 134 | 2,002 | 3,353 | 7,264 |

| San Leandro | 84,950 | 31,946 | 10,437 | 669 | 25,206 | 642 | 11,295 | 4,755 | 23,237 |

| Union City | 69,516 | 16,640 | 4,402 | 329 | 35,363 | 892 | 7,253 | 4,637 | 15,895 |

| Census-designated places |

Total Population |

White | African American |

Native American |

Asian | Pacific Islander |

other races |

two or more races |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| Ashland | 21,925 | 6,705 | 4,269 | 232 | 4,031 | 260 | 5,124 | 1,304 | 9,394 |

| Castro Valley | 61,388 | 35,602 | 4,260 | 329 | 13,140 | 417 | 3,757 | 3,883 | 10,689 |

| Cherryland | 14,728 | 6,035 | 1,698 | 200 | 1,404 | 310 | 4,016 | 1,065 | 7,955 |

| Fairview | 10,003 | 4,499 | 2,105 | 76 | 1,525 | 129 | 913 | 756 | 2,171 |

| San Lorenzo | 23,452 | 11,115 | 1,136 | 228 | 5,054 | 182 | 4,207 | 1,530 | 8,843 |

| Sunol | 913 | 780 | 1 | 6 | 48 | 7 | 19 | 52 | 91 |

| Other unincorporated areas |

Total Population |

White | African American |

Native American |

Asian | Pacific Islander |

other races |

two or more races |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

| All others not CDPs (combined) | 8,857 | 5,579 | 676 | 48 | 712 | 85 | 1,308 | 449 | 2,737 |

2000

[edit]As of the census[51] of 2000, there were 1,443,741 people, 523,366 households, out of which 32.6% had children under the age of 18 living within them, 47.0% married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.2% were non-families. 26.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.71 and the average family size was 3.31.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 24.6% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 33.9% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 10.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 96.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $55,946, and the median income for a family was $65,857 (these figures had risen to $66,430 and $81,341 respectively as of a 2007 estimate[52]). Males had a median income of $47,425 versus $36,921 for females. The per capita income for the county was $26,680. About 7.7% of families and 11.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.5% of those under age 18 and 8.1% of those age 65 or over.

In 2000, the largest denominational group was the Catholics (with 306,437 adherents).[53] The largest religious bodies were the Catholic Church (with 306,437 members) and Judaism (with 32,500 members).[53]

2019 United States Census Bureau American Community Survey estimates

[edit]|

Racial Makeup of Alameda County (2019)[54]

|

Racial Makeup of Alameda County excluding Hispanics from racial categories (2019)[54]

NH=Non-Hispanic

|

Racial Makeup of Hispanics in Alameda County (2019)[54]

|

According to 2019 US Census Bureau estimates, Alameda County's population was 38.8% White (30.4% Non-Hispanic White and 8.4% Hispanic White), 10.7% Black or African American, 31.1% Asian, 11.5% Some Other Race, 0.8% Native American and Alaskan Native, 0.8% Pacific Islander and 6.4% from two or more races.[54]

The White population continues to remain the largest racial category in Alameda County and includes the 37.7% of Hispanics who self-identify as White. The remainder of Hispanics self-identify as Other Race (49.2%), Multiracial (8.7%), American Indian and Alaskan Native (1.9%), Black (1.5%), Asian (0.9%), and Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (0.2%).[54]

The Black population continues to decline and at 10.7% (including Black Hispanics)[54] is below the national average of 12.8% (including Black Hispanics).[55] The Black population peaked in the 1980 Census at 18.4%.[56] Alameda county has the 2nd highest percentage of Black residents in California after Solano County at 13.4%.

If Hispanics are treated as a separate category from race, Alameda County's population was 30.4% White, 30.9% Asian, 22.3% Hispanic-Latino, 10.3% Black or African American, 0.5% Some Other Race, 0.3% Native American and Alaskan Native, 0.8% Pacific Islander and 4.4% from two or more races.[57]

Asian Americans are now the largest racial/ethnic group at 30.9% (excluding Asian Hispanics).[54]

White Non-Hispanic Americans are the largest minority group at 30.4% of the population.[54]

By ethnicity, 22.3% of the total population is Hispanic-Latino (of any race) and 77.7% is Non-Hispanic (of any race). If treated as a category separate from race, Hispanics are the third largest minority group in Alameda County.[54]

The largest ancestry group of Hispanics in Alameda County (2018) are of Mexican descent (72.9% of Hispanics) followed by Salvadoran descent (5.5% of Hispanics), Guatemalan descent (3.9%), Puerto Rican descent (3.4%), Spaniard descent (2.0%), Nicaraguan descent (1.7%), Peruvian descent (1.4%), Cuban descent (1.2%), Colombian descent (1.1%), and those of other Hispanic ethnicity or of mixed Hispanic ethnicity (6.9%).[58]

Crime

[edit]The following table includes the number of incidents reported and the rate per 1,000 persons for each type of offense.

| Population and crime rates in 2009 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population[22] | 1,494,876 | |

| Violent crime[59] | 11,189 | 7.48 |

| Homicide[59] | 138 | 0.09 |

| Forcible rape[59] | 553 | 0.37 |

| Robbery[59] | 5,215 | 3.49 |

| Aggravated assault[59] | 5,283 | 3.53 |

| Property crime[59] | 33,395 | 22.34 |

| Burglary[59] | 11,478 | 7.68 |

| Larceny-theft[59][note 4] | 32,102 | 21.47 |

| Motor vehicle theft[59] | 12,768 | 8.54 |

| Arson[59] | 457 | 0.31 |

Cities by population and crime rates

[edit]| Cities by population and crime rates in 2012 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[60] | Violent crimes[60] | Violent crime rate per 1,000 persons |

Property crimes[60] | Property crime rate per 1,000 persons | |||

| Alameda | 75,467 | 160 | 2.12 | 1,892 | 25.07 | |||

| Albany | 18,960 | 35 | 1.85 | 537 | 28.32 | |||

| Berkeley | 114,961 | 487 | 4.24 | 5,696 | 49.55 | |||

| Dublin | 49,890 | 84 | 1.79 | 731 | 15.55 | |||

| Emeryville | 10,309 | 175 | 16.98 | 1,735 | 168.30 | |||

| Fremont | 218,927 | 306 | 1.40 | 4,259 | 19.45 | |||

| Hayward | 147,424 | 613 | 4.16 | 4,792 | 32.50 | |||

| Livermore | 82,800 | 301 | 3.64 | 1,805 | 21.80 | |||

| Newark | 43,539 | 169 | 3.88 | 1,349 | 30.98 | |||

| Oakland | 399,487 | 7,963 | 19.93 | 26,342 | 65.94 | |||

| Piedmont | 10,909 | 13 | 1.19 | 333 | 30.53 | |||

| Pleasanton | 71,875 | 49 | 0.68 | 1,279 | 17.79 | |||

| San Leandro | 86,869 | 437 | 5.03 | 3,585 | 41.27 | |||

| Union City | 71,089 | 235 | 3.31 | 1,808 | 25.43 | |||

Education

[edit]The Alameda County Office of Education oversees seventeen K–12 school districts and one K–8 district in Alameda County. In all, there are approximately 10,000 teachers serving 225,000 students. The ACOE also services three community college districts with a total enrollment of approximately 55,000 students.

The Alameda County Library operates libraries in the cities of Albany, Dublin, Fremont, Newark and Union City and the unincorporated communities of Castro Valley and San Lorenzo. The cities of Alameda, Berkeley, Hayward, Livermore, Oakland, San Leandro, and Pleasanton have their own library systems.

Colleges and universities

[edit]Alameda County is home to the University of California, Berkeley, the flagship campus of the University of California system, and one of the largest and most prestigious research universities in the world.

Other colleges and universities located within Alameda county include:

- Berkeley City College

- California State University, East Bay, one of the campuses of the California State University system

- Chabot College, a two-year community college, part of the Chabot-Las Positas Community College District

- College of Alameda, a two-year community college, part of the Peralta Community College District of northern Alameda County

- Graduate Theological Union, a consortium of several Bay Area seminaries, affiliated with the University of California, Berkeley.

- Laney College, a two-year community college, part of the Peralta Community College system

- Las Positas College

- Merritt College, a two-year community college, part of the Peralta Community College system

- Mills College at Northeastern University, a private 4 year women's college and coeducational graduate school

- Ohlone College, part of the Ohlone Community College District

- Samuel Merritt University

Other local colleges and universities which have now closed include:

- SAE Expression College, a for-profit school specializing in creative media

- Holy Names University

Public schools

[edit]- School districts[61]

K–12 unified school districts:

- Alameda Unified School District

- Albany Unified School District

- Berkeley Unified School District

- Castro Valley Unified School District

- Dublin Unified School District

- Emery Unified School District

- Fremont Unified School District

- Hayward Unified School District

- Livermore Valley Joint Unified School District

- New Haven Unified School District

- Newark Unified School District

- Oakland Unified School District

- Piedmont Unified School District

- Pleasanton Unified School District

- San Leandro Unified School District

- San Lorenzo Unified School District

- Sunol Glen Unified School District

Others:

- Lammersville Joint Unified School District (high)

- Mountain House Elementary School District (elementary)

- State-operated schools

Arts

[edit]The Alameda County Arts Commission, a division of the county administration, under the California Arts Council, was created in 1965. Its fifteen appointed members act in an advisory capacity to the board of supervisors, in promoting the arts. The Oakland Museum of California has a substantial collection of California art works and historical artifacts.

Sports

[edit]The following sports teams play in Alameda County:

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California Golden Bears | NCAA | 1868 | NCAA: ACC | California Memorial Stadium (Football), Haas Pavilion (Basketball), Evans Diamond (Baseball) |

| East Bay FC Stompers | Soccer | 2012 (in San Francisco from 2012 to 2015) | National Premier Soccer League: Golden Gate Conference | Pioneer Stadium |

| Oakland Roots | Soccer | 2018 | USL Championship | Pioneer Stadium |

Events

[edit]The annual county fair is held at the Alameda County Fairgrounds in Pleasanton. The fair runs for four weekends from June to July. Attractions include horse racing, carnival rides, 4-H exhibits, and live bands.

Parks and recreation

[edit]There are more than 350 parks located within the county.[62] The East Bay Regional Park District operates within Alameda and neighboring Contra Costa County, with numerous parks within the county, including Tilden Regional Park, Redwood Regional Park, Anthony Chabot Regional Park, Coyote Hills Regional Park, Ardenwood Historic Farm, Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park and Vargas Plateau Regional Park. Eastshore State Park is located partially along the bay shore of northern Alameda County. The San Francisco Bay Trail, a project of the Association of Bay Area Governments, will run along the bay shore of the county.[63] The Hayward Area Recreation and Park District is the largest special park district in California.

Transportation

[edit]Major highways

[edit] I-80

I-80 I-205

I-205

I-238 / SR 238

I-238 / SR 238 I-580

I-580 I-680

I-680 I-880

I-880 I-980

I-980 SR 13

SR 13 SR 24

SR 24 SR 61

SR 61 SR 77

SR 77 SR 84

SR 84 SR 92

SR 92 SR 123 – former US 40

SR 123 – former US 40 SR 185

SR 185 SR 262

SR 262

Mass transit

[edit]Rail

[edit]- Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) – commuter rail using existing railroad tracks; primarily brings commuters from San Joaquin County to Santa Clara County

- Amtrak

- California Zephyr – intercity train route running between Emeryville and Chicago.

- Capitol Corridor – commuter rail using existing railroad tracks, extending from San Jose to Sacramento, running through western Alameda County

- Coast Starlight – intercity train route running between Los Angeles and Seattle via Oakland and Emeryville

- Gold Runner – Amtrak route between Oakland and Bakersfield through Fresno and the Central Valley

- Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) – rapid transit commuter rail centered on northwest Oakland, primarily serving commuters to downtown San Francisco and downtown Oakland

- Valley Link – planned commuter rail running between the Tri-Valley and San Joaquin County (expected to commence in 2028)

Bus

[edit]- AC Transit – local bus system in western Alameda County and west Contra Costa County, with additional service across the three bridges from Alameda County to downtown San Francisco, San Mateo, and Palo Alto

- WHEELS – bus system in the cities of southeastern Alameda County

- Union City Transit – local city bus service within Union City in addition to AC Transit

- Emery-Go-Round – free bus service in Emeryville

- Dumbarton Express – additional service across the Dumbarton Bridge between Fremont and Palo Alto

- Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) – commuter service between southern Alameda county and job centers in the Silicon Valley

Ferry

[edit]- Alameda / Oakland Ferry and Harbor Bay Ferry – connect Oakland, Alameda, and Bay Farm Island with downtown San Francisco

Airports

[edit]The main airport is the Oakland San Francisco Bay Airport, with two general aviation airports, the Hayward Executive Airport and Livermore Municipal Airport.

Services

[edit]Alameda Health System operates the public health system in Alameda County. It operates five hospitals (Alameda Hospital, Fairmont Hospital, Highland Hospital, John George Psychiatric Hospital, and San Leandro Hospital), and four primary care medical clinics (called ambulatory wellness centers) within the county.

The Alameda County Community Food Bank nonprofit provides food bank resources to residents. The Family Emergency Shelter Coalition coordinates services for homeless families.

Landmarks

[edit]Alameda County has eight National Historic Landmarks: The Abbey, Joaquin Miller House, First Church of Christ, Scientist, USS Hornet (CVS-12) (aircraft carrier), Lake Merritt Wild Duck Refuge, Lightship WAL-605, Relief, Paramount Theatre, Potomac (Presidential yacht), and Room 307, Gilman Hall, University of California. The county has a large number of National Historic Places, as well as a number of California Historical Landmarks.

Sister counties

[edit]Alameda has two sister county: Taoyuan County, Taiwan (now Taoyuan City) and Zhongshan in China.[64]

Communities

[edit]

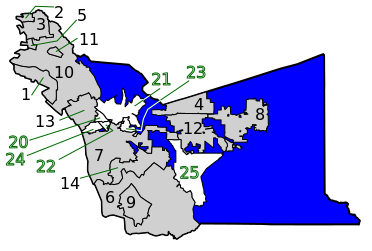

Cities

[edit]| No. on Map |

City | Year incorporated |

Population, 2020[65] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alameda | 1854 | 78,280 |

| 2 | Albany | 1908 | 20,271 |

| 3 | Berkeley | 1878 | 124,321 |

| 4 | Dublin | 1982 | 72,589 |

| 5 | Emeryville | 1896 | 12,905 |

| 6 | Fremont | 1956 | 230,504 |

| 7 | Hayward | 1876 | 162,954 |

| 8 | Livermore | 1876 | 87,955 |

| 9 | Newark | 1955 | 47,529 |

| 10 | Oakland (county seat) | 1852 | 440,646 |

| 11 | Piedmont | 1907 | 11,270 |

| 12 | Pleasanton | 1894 | 79,871 |

| 13 | San Leandro | 1872 | 91,008 |

| 14 | Union City | 1959 | 70,143 |

Census-designated places

[edit]Unincorporated communities

[edit]Former townships

[edit]

- Oakland Township – the northern portion subsequently became the cities of Berkeley and Albany.

- Alameda Township – now essentially coterminous with the City of Alameda.

- Brooklyn Township – mostly contained within Oakland and Piedmont.

- Eden Township – partly incorporated into San Leandro and Hayward, the rest contains the communities of Castro Valley, San Lorenzo, and other unincorporated areas.

- Washington Township – contains Union City, Newark, Fremont, and small unincorporated areas nearby.

- Murray Township — Contains cities of Dublin, Pleasanton, and Livermore, and substantial unincorporated areas including Sunol.

Population ranking

[edit]The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2020 census of Alameda County.[66]

† county seat

| Rank | City/Town/etc. | Municipal type | Population (2020 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | † Oakland | City | 440,646 |

| 2 | Fremont | City | 230,504 |

| 3 | Hayward | City | 162,954 |

| 4 | Berkeley | City | 124,321 |

| 5 | San Leandro | City | 91,008 |

| 6 | Livermore | City | 87,955 |

| 7 | Pleasanton | City | 79,871 |

| 8 | Alameda | City | 78,280 |

| 9 | Dublin | City | 72,589 |

| 10 | Union City | City | 70,143 |

| 11 | Castro Valley | CDP | 66,441 |

| 12 | Newark | City | 47,529 |

| 13 | San Lorenzo | CDP | 29,581 |

| 14 | Ashland | CDP | 23,823 |

| 15 | Albany | City | 20,271 |

| 16 | Cherryland | CDP | 15,808 |

| 17 | Emeryville | City | 12,905 |

| 18 | Fairview | CDP | 11,341 |

| 19 | Piedmont | City | 11,270 |

| 20 | Sunol | CDP | 922 |

See also

[edit]- USS Alameda County (LST-32), the only US Naval vessel named after the county

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Alameda County, California

- Solar power in Alameda County

- List of counties in California

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Percentage of registered voters with respect to total population. Percentages of party members with respect to registered voters follow.

- ^ Other = Some other race + Two or more races

- ^ Native American = Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander + American Indian or Alaska Native

- ^ Only larceny-theft cases involving property over $400 in value are reported as property crimes.

References

[edit]- ^ "Alameda County". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ "Home | Board of Supervisors | Alameda County". bos.acgov.org.

- ^ "Discovery Peak". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau. 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product: All Industries in Alameda County, CA". fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ "Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ About Alameda County – County of Alameda – Superior Court of California Archived June 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Alameda.courts.ca.gov. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "ALAMEDA English Definition and Meaning". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Definition of ALAMEDA". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ California Government Code § 23004

- ^ "Board of Supervisors". Alameda County. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Morris, Scott (July 15, 2021). "Alameda County District Attorney Nancy O'Malley is stepping aside". The Oaklandside. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Sharpe, Joshua (November 19, 2022). "Civil rights attorney Pamela Price makes history as Alameda County's next district attorney". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Alameda County Fire Department". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- ^ "Senators". State of California. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- ^ pres_general_ssov_for_all.xls

- ^ a b Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ "Statement of Vote" (PDF). www.sos.ca.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Statement of Vote, November 8, 2022, General Election" (PDF). California Secretary of State. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B02001. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f California Secretary of State. February 10, 2013 – Report of Registration Archived July 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ "CA Oakland Museum". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ "LIVERMORE, CALIFORNIA – Climate Summary". www.wrcc.dri.edu. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "Климат Ливермора – Погода и климат". www.pogodaiklimat.ru. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ "Why Is Part of Alameda Island in San Francisco?". KQED. November 1, 2018.

- ^ "The National Map - Advanced Viewer".

- ^ "QuickFacts Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 9, 2025.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing from 1790-2000". US Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "California: 1980, General Social and Economic Characteristics, Part 1" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "California: 1990, Part 1" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ Narula, Svati Kirsten (April 29, 2014). "The 5 U.S. Counties Where Racial Diversity Is Highest—and Lowest". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ "Justice Map - Visualize race and income data for your community". Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B03003. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19301. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19013. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19113. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B01003. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "2010 Census P.L. 94-171 Summary File Data". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Bay Area Census". www.bayareacensus.ca.gov.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Community Facts > Alameda County, California". Archived from the original on February 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "County Membership Reports". thearda.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "B03002 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY RACE – Alameda County, California – 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "B03002 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY RACE – United States – 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Alameda County Decennial Census data". Bay Area Census. Archived from the original on October 11, 2004. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "B03002 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY RACE – Alameda County, California – 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "B03001 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN – Alameda County, California – 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Office of the Attorney General, Department of Justice, State of California. Table 11: Crimes – 2009 Archived December 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2012, Table 8 (California). Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Alameda County, CA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 19, 2022. - Text list

- ^ Alameda County California Parks. California.hometownlocator.com. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ San Francisco Baytrail. Baytrail.abag.ca.gov. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ Alameda – Taoyuan Sister County Association – Homepage. Acgov.org. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Alameda County, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "By Decade".

External links

[edit]- Official website

- map of Alameda County with supervisorial district boundaries

- Alameda County Fairgrounds – Annual county fair June to July

- A short film about Alameda County from 1958

- Alameda County Fire Department Archived March 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Alameda County Fire Department Training Division

- Hiking trails in Alameda County, at the Berkeley Wiki website

Alameda County, California

View on GrokipediaGeography

Physical Features and Climate

Alameda County lies in the East Bay portion of the San Francisco Bay Area, encompassing a varied terrain of coastal lowlands, alluvial plains, and inland hills. The western sector features flatlands along the San Francisco Bay shoreline, including reclaimed marshes and the elongated Alameda Island, while the central region rises into the Oakland Hills with elevations up to 2,500 feet at peaks like Mission Peak.[9] To the east, the landscape opens into the Livermore Valley, flanked by foothills of the Diablo Range that reach higher elevations around 3,000 feet, shaped by tectonic uplift and erosion.[10] This topography results from ongoing plate boundary interactions along the San Andreas Fault system, promoting seismic activity.[10] The county's primary water features include over 100 miles of San Francisco Bay waterfront, forming estuaries and tidal flats that influence sediment deposition and coastal morphology. The bay's proximity creates microclimatic variations, with evaporation cooling summer air along the shore and retaining heat to temper winter lows. Inland areas experience greater diurnal temperature swings due to less maritime moderation.[11] Alameda County exhibits a Mediterranean climate, with mild temperatures, low annual precipitation, and distinct seasonal patterns driven by Pacific storm tracks. Average annual rainfall measures approximately 22 inches, mostly falling between October and April, while summers remain arid with negligible precipitation. High temperatures average 58°F in January and 74°F in September, with lows rarely dropping below 37°F or exceeding 85°F annually.[12] [13] Seismically, the Hayward Fault bisects the county, generating right-lateral strike-slip motion and posing high risk for destructive quakes; models indicate a magnitude 6.9 event could rupture 50-70 miles, amplifying ground shaking in sedimentary basins of the flatlands and causing liquefaction in bay-adjacent zones. This fault's activity has historically limited dense development on unstable slopes, channeling urban growth to stable plains, though flood vulnerability persists in low-elevation areas prone to tidal surges and subsidence.[14] [15]Boundaries and Adjacent Areas

Alameda County encompasses approximately 739 square miles, including 656 square miles of land and 82 square miles of water, primarily from the San Francisco Bay. Its boundaries are legally defined in California Government Code Section 23006, commencing at the intersection of the southern boundary of Contra Costa County and extending along specified lines through natural features and survey points.[16] [17] The county shares land borders with three adjacent counties: Contra Costa County to the north, along the crest of the Berkeley Hills and segments near the Carquinez Strait; San Joaquin County to the east, primarily through the Livermore Valley and Altamont Pass region; and Santa Clara County to the south, delineated by ridgelines such as those of Mission Peak. To the west, the San Francisco Bay forms a water boundary, separating Alameda County from San Francisco and San Mateo counties without direct terrestrial contiguity to the latter, though proximity across the bay influences regional interactions via bridges like the San Mateo Bridge.[18] [19] Portions of the county's boundaries incorporate protected natural areas managed collaboratively with neighbors, notably through the East Bay Regional Park District, which administers 73 parks totaling 125,496 acres across Alameda and Contra Costa counties, including shoreline and hillside preserves along their shared northern frontier. This district facilitates cross-boundary conservation and recreation, with trails and habitats extending seamlessly into adjacent jurisdictions.[20] Geographic adjacency drives economic interdependencies, including substantial cross-county commuting; for instance, many residents travel daily to Contra Costa via State Route 24 or to Santa Clara via Interstate 680, contributing to integrated labor markets in the East Bay subregion. U.S. Census Bureau data reflect this, showing over 40% of Alameda County workers commuting outside the county, underscoring the blurred functional boundaries despite formal lines.[21][22]History

Indigenous and Early Settlement Periods

The territory comprising present-day Alameda County was long inhabited by Ohlone (also known as Costanoan) peoples, whose ancestors occupied the San Francisco Bay Area for at least 2,000 years, as demonstrated by ancient DNA analysis from burial sites linking modern Muwekma Ohlone descendants to pre-colonial remains near Mission San Jose and other East Bay locations.[23] Archaeological evidence, including shell middens and village sites along creeks like San Lorenzo and Alameda, indicates semi-sedentary communities that exploited diverse ecosystems through acorn gathering, fishing in the Bay, hunting deer and rabbits, and seasonal migrations for resources, with estimated pre-contact populations in the thousands across the peninsula and East Bay.[24] These groups, part of broader Ohlone linguistic and cultural clusters, maintained villages such as those near modern Fremont and Oakland, practicing controlled burns for habitat management and trade networks extending to Central Valley tribes.[25] European contact began with the Portolá expedition in 1769–1770, which traversed the East Bay but left initial impacts limited to transient exploration; sustained colonization followed with the establishment of Mission San José in 1797, drawing local Ohlone bands into coerced labor systems for agriculture and herding, resulting in catastrophic population declines from introduced diseases like smallpox and syphilis, as well as malnutrition and violence, reducing Bay Area Ohlone numbers from approximately 7,000–10,000 in 1770 to under 2,000 by the 1830s.[24] Mission records document neophyte resistance through flight and uprisings, yet systemic encomienda-style exploitation integrated survivors into ranchos post-secularization under Mexican rule after 1834, fragmenting traditional land use and dispersing communities into small rancherías.[26] Under Mexican governance from 1821, large ranchos were granted to Californio elites, including the 44,800-acre Rancho San Antonio awarded to Luís María Peralta in 1820 (confirmed in 1842), encompassing much of modern Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda, used primarily for cattle ranching on former Ohlone territories.[27] Other grants, such as Arroyo de la Alameda (Bartolomé Pacheco, 1839) and Rancho San Lorenzo (Guillermo Castro, 1841), facilitated hacienda-style operations reliant on peon labor from mission remnants.[28] The U.S. conquest via the Bear Flag Revolt (1846) and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) introduced American squatters challenging Mexican titles, accelerated by the Gold Rush discovery at Sutter's Mill in January 1848, which drew thousands of migrants seeking Bay Area ports and fertile valleys for provisioning mines, initiating subdivision of ranchos through legal claims under the Land Act of 1851.[29] Alameda County was formally established on May 10, 1853, carved from northern portions of Santa Clara County and eastern segments of Contra Costa County to accommodate growing Anglo-American settlements in the East Bay, with initial boundaries reflecting the need for local governance amid rapid influxes of farmers and speculators displacing remaining Ohlone and Californio landholders.[2] Early county organization centered on provisional seats like San Leandro, marking the transition from indigenous and Hispanic pastoralism to U.S. agrarian expansion.[30]Industrialization and Urban Growth (1850–1945)

Oakland, the county's largest city, was incorporated on May 4, 1852, amid the California Gold Rush's population influx, establishing it as a key East Bay hub for trade and settlement.[31] Berkeley followed with incorporation on April 4, 1878, driven by the University of California's relocation and suburban expansion needs.[32] These incorporations facilitated infrastructural growth, including the arrival of the first transcontinental railroad's western terminus in Oakland in 1869, which spurred port development along the waterfront and connected the region to national markets via rail lines extending eastward along the estuary.[31] By the late 19th century, the Port of Oakland emerged as a vital deepwater facility, handling Gold Rush-era cargo and later agricultural exports, with waterfront control shifting to municipal oversight by 1910 to enable systematic expansion.[33][34] Industrial diversification accelerated post-1900, with food processing dominating as Alameda County's primary peacetime industry; the region led California in canned fruit and vegetable output, supported by five major canneries, including the large Hunt Brothers facility in Hayward that processed local harvests of apricots, pears, and other produce.[35][36] Rail and port infrastructure enabled efficient transport of these goods, while early manufacturing clusters formed along the Oakland estuary, leveraging proximity to San Francisco Bay for shipping. Shipbuilding also took root along the estuary and Alameda Point, producing wooden hulls for lumber schooners and coastal vessels by the early 20th century.[37] The 1906 San Francisco earthquake inflicted significant damage across Alameda County, toppling brick structures and frame houses in Oakland, Alameda, and Berkeley, while causing liquefaction at waterfronts.[38][39] However, the disaster redirected growth eastward, drawing over 150,000 refugees to Oakland and fueling a construction boom that doubled its population by 1910 and enhanced port infrastructure.[40][41] World War I and II amplified naval and shipbuilding activities, particularly in Alameda, where facilities on the North Shore constructed troop transports and repaired vessels; by World War II, the commissioning of Naval Air Station Alameda in 1940 supported aircraft manufacturing and maintenance across 271 trades, contributing to the Bay Area's output of over 1,400 ships between 1940 and 1945.[42][43][44] These wartime efforts industrialized the waterfront further, employing thousands and solidifying the county's role in defense production through 1945.[45]Postwar Expansion and Suburbanization (1946–2000)

Following World War II, Alameda County experienced rapid population growth driven by the baby boom and migration to California for economic opportunities, with the population increasing from 740,315 in 1950 to 990,038 by 1960, a 34% rise attributed to influxes of veterans and families seeking suburban housing.[46] This expansion was facilitated by extensive freeway construction under the Interstate Highway System, initiated in 1956, including segments of I-80, I-580, and I-880 through the county in the late 1950s and 1960s, which enabled automobile-dependent suburban development in areas like Fremont and Livermore.[47] These infrastructure projects supported the shift from urban density in Oakland and Berkeley to sprawling residential tracts, converting agricultural lands into housing subdivisions amid postwar housing demand.[48] The inception of Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) in the 1960s responded to this suburban surge, with planning dating to 1946 but construction commencing in 1964, including Oakland subway segments by 1966, aimed at connecting East Bay suburbs to San Francisco employment centers.[49] Economic diversification emerged through spillover from Silicon Valley's nascent tech sector in adjacent counties and the influence of the University of California, Berkeley, which expanded enrollment and research post-1945, drawing skilled workers and fostering ancillary industries in the East Bay. However, unchecked development prompted environmental activism, notably the 1961 founding of Save the Bay by East Bay residents opposing bay fill projects that threatened estuarine habitats, leading to the 1965 McAteer-Petris Act establishing the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission to regulate land-use changes.[50][51] The period culminated in the October 17, 1989, Loma Prieta earthquake, magnitude 6.9, which caused significant infrastructure damage in Alameda County, including the collapse of the Cypress Street Viaduct on I-880 in Oakland, killing 42 people and disrupting suburban commuting patterns. The event, centered 70 miles south in Santa Cruz County, resulted in over $6 billion in regional damage, with Alameda County facing liquefaction in areas like Harbor Bay and prompting seismic retrofits that influenced subsequent land-use planning and suburban resilience measures.[52][53] Despite these shocks, the county's population stabilized around 1.3 million by 1990, reflecting a maturing suburban landscape shaped by transportation, economic drivers, and regulatory responses to growth pressures.[46]Modern Developments and Challenges (2001–Present)

Following the dot-com bust of 2000–2002, which slowed office market recovery in Alameda County due to reduced demand from tech firms, the local economy rebounded through diversification into professional services and adjacent sectors. By the 2010s, the Oakland-Hayward-Berkeley metropolitan area, encompassing much of the county, experienced steady job growth in professional, scientific, and technical services, adding positions even during national recessions, as this sector expanded by over 20% from 2000 to 2018. Biotech emerged as a key driver, with the industry generating approximately $850 million in economic impact and 4,700 jobs in Alameda County by 2013, clustered in areas like Emeryville and fostering ecosystems for life sciences and cleantech innovation.[54][55][56][57] Housing affordability emerged as a persistent challenge amid population pressures and regulatory constraints, prompting the county to adopt a 10-Year Housing Plan in July 2025 to address the crisis through targeted investments and streamlined permitting. This framework builds on the 6th Cycle Housing Element for 2023–2031, which mandates accommodating 4,711 new units in unincorporated areas via zoning reforms and incentives for affordable development, though implementation faces hurdles from community resistance and infrastructure limits. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated shortages, with remote work shifts contributing to Bay Area office vacancy rates reaching 24% by 2025, reducing downtown Oakland foot traffic and straining commercial real estate tied to housing demand.[58][59][60] The Port of Oakland, a vital economic engine handling over 99% of Northern California's containerized imports, navigated COVID-19 disruptions with initial volume dips in early 2020 followed by surges, including record cargo levels in 2021 driven by e-commerce demand and supply chain shifts, though persistent congestion highlighted vulnerabilities in labor and logistics. Meanwhile, Oakland grappled with accelerating urban challenges, including a 70% rise in homelessness by 2025, with encampments proliferating despite policies like the 2021 Encampment Management approach that closed over 500 sites by 2023 but left 1,500 unresolved, correlating with progressive governance emphases on non-enforcement and shelter-first strategies that empirical outcomes suggest have yielded limited containment amid fiscal strains.[61][4][62][63][64][65][66]Government and Politics

County Governance Structure

Alameda County operates as a charter county under the California Constitution, with its charter adopted by voters on November 4, 1980, granting it home rule authority beyond general law counties.[67] The county's legislative and executive powers are vested in a five-member Board of Supervisors, elected to staggered four-year terms from single-member districts on a non-partisan basis.[68] The Board enacts ordinances, adopts the annual budget, appoints department heads and advisory boards, and oversees county operations including public health, social services, and infrastructure in unincorporated areas.[69] It also exercises quasi-judicial functions, such as hearing appeals on land use and zoning matters.[70] Key elected officials independent of the Board include the Assessor, who determines property values for taxation purposes to ensure fair assessment ratios under Proposition 13; the Sheriff-Coroner, responsible for law enforcement in unincorporated areas, operating county jails, serving civil processes, and conducting death investigations; and the District Attorney, who prosecutes violations of state law and county ordinances, advises law enforcement, and represents the county in civil actions.[71][72][70] These row offices maintain autonomy to prevent consolidation of power, differing from city governance where councils often directly appoint department heads without separate constitutional elections for such roles.[73] The county budget process begins with departmental submissions in early calendar year, followed by review by the County Administrator's office, public hearings, and final adoption by the Board no later than June 30 for the fiscal year starting July 1.[74] For fiscal year 2025-2026, the proposed $5.1 billion budget addressed a $105.7 million structural deficit through expenditure controls, revenue enhancements, and one-time reserves, amid declining state supplemental funding and regional tech sector layoffs impacting sales and property tax revenues.[75][76] Unlike cities, which focus on municipal services like local policing and zoning within boundaries, county budgets encompass mandatory statewide programs such as welfare and probation, exposing them to broader fiscal volatilities from state policy shifts.[70]Electoral Representation

Alameda County is apportioned across three United States congressional districts as established by the California Citizens Redistricting Commission's maps adopted in December 2021, following the 2020 United States Census and effective for elections starting in 2022.[77] These boundaries reflect population shifts, with denser urban areas in the western county (such as Oakland and Berkeley) consolidated in the 12th District, central suburban zones (including Fremont and Hayward) in the 14th, and southeastern suburban-rural expanses (such as Pleasanton and parts of Fremont) in the 17th, thereby delineating urban cores from peripheral growth areas without crossing major geographic divides like the Diablo Range foothills.[77] The current representatives, serving terms beginning January 3, 2025, after the November 2024 elections, are:| District | Representative | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 12th | Lateefah Simon | Democrat[78] |

| 14th | Eric Swalwell | Democrat[79] |

| 17th | Ro Khanna | Democrat |

| District | Senator | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 7th | Jesse Arreguín | Democrat[80] |

| 9th | Tim Grayson | Democrat[80] |

| 10th | Aisha Wahab | Democrat[81] |

| District | Assemblymember | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 14th | Buffy Wicks | Democrat |

| 16th | Rebecca Bauer-Kahan | Democrat[82] |

| 18th | Mia Bonta | Democrat[83] |

| 20th | Liz Ortega | Democrat[84] |

| 24th | Alex Lee | Democrat |

Voter Demographics and Political Trends

Alameda County maintains a pronounced Democratic Party advantage in voter registration, with 57.9% of registered voters (558,980 individuals) affiliated with the Democrats as of the latest county data.[85] No Party Preference registrants comprise 24.7% (238,627), while Republican affiliation remains minimal at under 10%, alongside smaller shares for parties such as American Independent (2.8%), Green (0.7%), and Libertarian (0.7%).[85] This partisan imbalance reflects broader Bay Area patterns, where Democratic registration has hovered above 50% since at least the 1990s, driven by urban and suburban demographics favoring progressive policies on issues like housing, environment, and social services. Presidential election results underscore this dominance, with Democratic candidates consistently securing margins exceeding 60% since 1992. In 2000, Al Gore received 69.4% of the vote against George W. Bush's 24.2%; by 2020, Joe Biden captured 79.8% to Donald Trump's 17.6%.[86][87] Voter turnout in countywide elections typically aligns with state averages, reaching around 80% in high-stakes presidential cycles, though lower in off-year contests. Empirical data indicate that while registration tilts heavily Democratic, actual voting behavior shows some cross-over from independents, yet the county's one-party electoral lock has correlated with stagnant economic mobility and elevated urban crime rates in areas like Oakland, where property crimes rose 20% annually from 2020 to 2023 under aligned local leadership.[88] Recent trends reveal fissures in this hegemony, particularly backlash against far-left prosecutorial and administrative approaches. In November 2024, voters recalled Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price by a 62.9% to 37.1% margin, citing leniency policies linked to recidivism spikes.) Concurrently, Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao faced successful recall with over 50% support, reflecting discontent with governance amid rising homicides and retail thefts that exceeded state averages by 40% during her tenure.[89] These outcomes, amid 58% Democratic registration, signal a pragmatic revolt within the electorate against ideological extremes, as moderate and independent voters prioritized public safety and fiscal accountability over partisan loyalty—evident in similar 2022-2024 municipal upsets across California urban counties.[90]Governance Controversies and Reforms