Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dehydration

View on Wikipedia

| Dehydration | |

|---|---|

| |

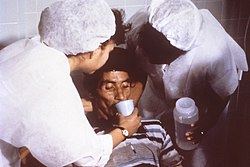

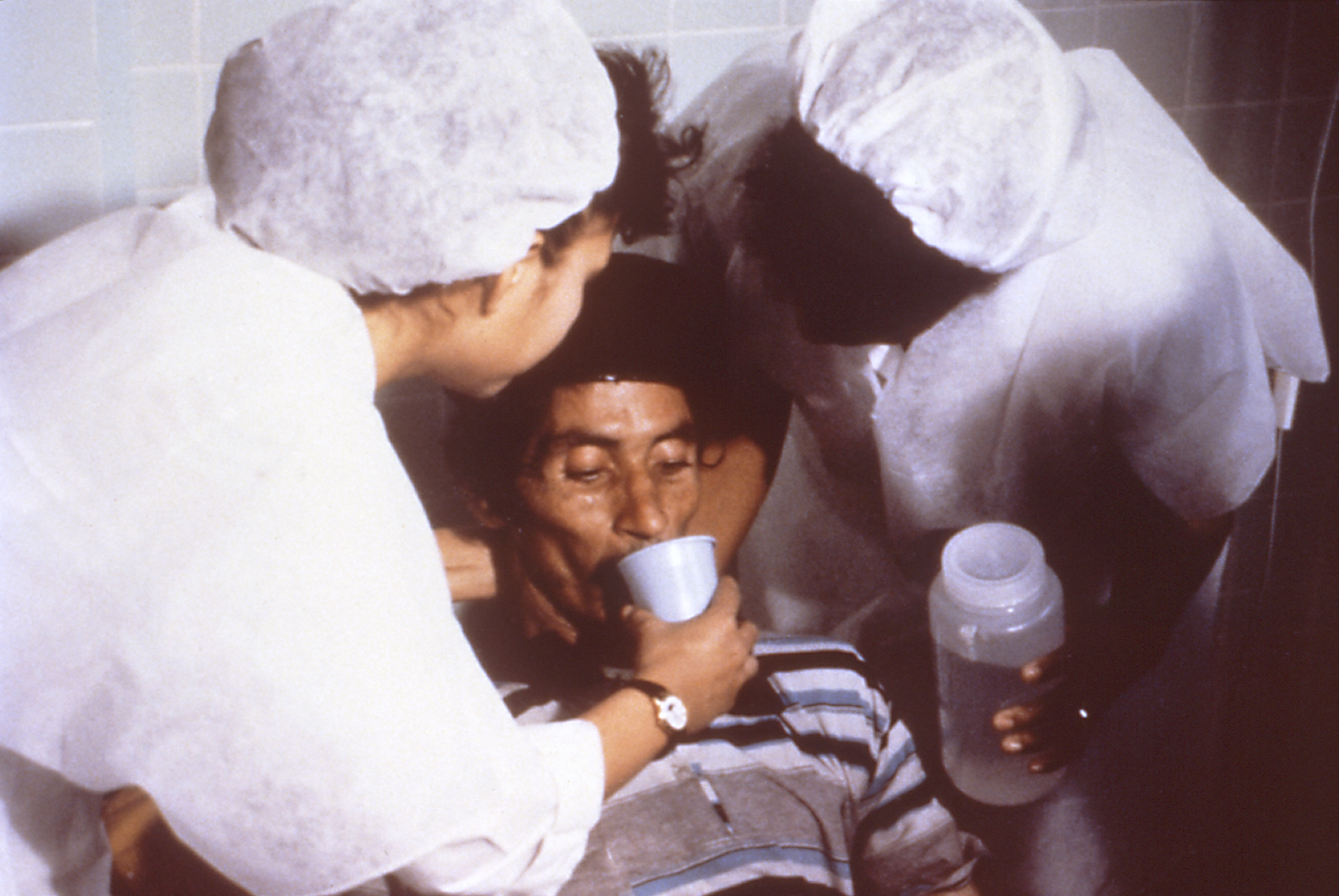

| Nurses encourage a patient to drink an oral rehydration solution to treat dehydration caused by cholera. | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Increased thirst, tiredness, decreased urine, dizziness, headaches, and confusion[1] |

| Complications | Low blood volume shock (hypovolemic shock), coma, seizures, urinary tract infection, kidney disease, heatstroke, hypernatremia, metabolic disease,[1] hypertension[2] |

| Causes | Loss of body water |

| Risk factors | Physical water scarcity, heatwaves, disease (most commonly from diseases that cause vomiting and/or diarrhea), exercise |

| Treatment | Drinking clean water |

| Medication | Saline |

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes.[3] It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild dehydration can also be caused by immersion diuresis, which may increase risk of decompression sickness in divers.

Most people can tolerate a 3–4% decrease in total body water without difficulty or adverse health effects. A 5–8% decrease can cause fatigue and dizziness. Loss of over 10% of total body water can cause physical and mental deterioration, accompanied by severe thirst. Death occurs with a 15 and 25% loss of body water.[4] Mild dehydration usually resolves with oral rehydration, but severe cases may need intravenous fluids.

Dehydration can cause hypernatremia (high levels of sodium ions in the blood). This is distinct from hypovolemia (loss of blood volume, particularly blood plasma).

Chronic dehydration can cause kidney stones as well as the development of chronic kidney disease.[5][6]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The hallmarks of dehydration include thirst and neurological changes such as headaches, general discomfort, loss of appetite, nausea, decreased urine volume (unless polyuria is the cause of dehydration), confusion, unexplained tiredness, purple fingernails, and seizures.[7] The symptoms of dehydration become increasingly severe with greater total body water loss. A body water loss of 1–2%, considered mild dehydration, is shown to impair cognitive performance.[8] While in people over age 50, the body's thirst sensation diminishes with age, a study found that there was no difference in fluid intake between young and old people.[9] Many older people have symptoms of dehydration, with the most common being fatigue.[10] Dehydration contributes to morbidity in the elderly population, especially during conditions that promote insensible free water losses, such as hot weather.

Cause

[edit]Risk factors for dehydration include but are not limited to: exerting oneself in hot and humid weather, habitation at high altitudes, endurance athletics, elderly adults, infants, children and people living with chronic illnesses.[11][12][13][14]

Dehydration can also come as a side effect from many different types of drugs and medications.[15]

In the elderly, blunted response to thirst or inadequate ability to access free water in the face of excess free water losses (especially hyperglycemia related) seem to be the main causes of dehydration.[16] Excess free water or hypotonic water can leave the body in two ways – sensible loss such as osmotic diuresis, sweating, vomiting and diarrhea, and insensible water loss, occurring mainly through the skin and respiratory tract. In humans, dehydration can be caused by a wide range of diseases and states that impair water homeostasis in the body. These occur primarily through either impaired thirst/water access or sodium excess.[17]

Mechanism

[edit]

Water content of a human body varies from 70–75% in newborns to 40% and less in obese adults,[19] an average value of 60% is suggested.[20] Within the body, water is classified as intracellular fluid or extracellular fluid. Intracellular fluid refers to water that is contained within the cells. This consists of approximately 57% of the total body water weight.[19] Fluid inside the cells has high concentrations of potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and proteins.[21] Extracellular fluid consists of all fluid outside of the cells, and it includes blood and interstitial fluid. This makes up approximately 43% of the total body water weight. The most common ions in extracellular fluid include sodium, chloride, and bicarbonate.

The concentration of dissolved molecules and ions in the fluid is described as Osmolarity and is measured in osmoles per liter (Osm/L).[21] When the body experiences a free water deficit, the concentration of solutes is increased. This leads to a higher serum osmolarity. When serum osmolarity is elevated, this is detected by osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus. These receptors trigger the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH).[22] ADH resists dehydration by increasing water absorption in the kidneys and constricting blood vessels. It acts on the V2 receptors in the cells of the collecting tubule of the nephron to increase expression of aquaporin. In more extreme cases of low blood pressure, the hypothalamus releases higher amounts of ADH which also acts on V1 receptors.[23] These receptors cause contractions in the peripheral vascular smooth muscle. This increases systemic vascular resistance and raises blood pressure.

Diagnosis

[edit]Definition

[edit]Dehydration occurs when water intake does not replace free water lost due to normal physiologic processes, including breathing, urination, perspiration, or other causes, including diarrhea, and vomiting. Dehydration can be life-threatening when severe and lead to seizures or respiratory arrest, and also carries the risk of osmotic cerebral edema if rehydration is overly rapid.[24]

The term "dehydration" has sometimes been used incorrectly as a proxy for the separate, related condition of hypovolemia, which specifically refers to a decrease in volume of blood plasma.[3] The two are regulated through independent mechanisms in humans;[3] the distinction is important in guiding treatment.[25]

Physical examination

[edit]Common exam findings of dehydration include dry mucous membranes, dry axillae, increased capillary refill time, sunken eyes, and poor skin turgor.[27][10] More extreme cases of dehydration can lead to orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, weakness, and altered mental status.[28] Depending on the underlying cause of dehydration, other symptoms may be present as well. Excessive sweating from exercise may be associated with muscle cramps. Patients with gastrointestinal water loss from vomiting or diarrhea may also have fever or other systemic signs of infection.

The skin turgor test can be used to support the diagnosis of dehydration. The skin turgor test is conducted by pinching skin on the patient's body, in a location such as the forearm or the back of the hand, and watching to see how quickly it returns to its normal position. The skin turgor test can be unreliable in patients who have reduced skin elasticity, such as the elderly.[29]

Laboratory tests

[edit]While there is no single gold standard test to diagnose dehydration, evidence can be seen in multiple laboratory tests involving blood and urine. Serum osmolarity above 295 mOsm/kg is typically seen in dehydration due to free water loss.[10] A urinalysis, which is a test that performs chemical and microscopic analysis of urine, may find darker color or foul odor with severe dehydration.[30] Urinary sodium also provides information about the type of dehydration. For hyponatremic dehydration, such as from vomiting or diarrhea, urinary sodium will be less than 10 mmol/L due to increased sodium retention by the kidneys in an effort to conserve water.[31] In dehydrated patients with sodium loss due to diuretics or renal dysfunction, urinary sodium may be elevated above 20 mmol/L.[32] Patients may also have elevated serum levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine. Both of these molecules are normally excreted by the kidney, but when the circulating blood volume is low, the kidney can become injured.[33] This causes decreased kidney function and results in elevated BUN and creatinine in the serum.[34]

Prevention

[edit]For routine activities, thirst is normally an adequate guide to maintain proper hydration.[35] Minimum water intake will vary individually depending on weight, energy expenditure, age, sex, physical activity, environment, diet, and genetics.[36][37] With exercise, exposure to hot environments, or a decreased thirst response, additional water may be required. In athletes in competition, drinking to thirst optimizes performance and safety, despite weight loss, and as of 2010, there was no scientific study showing that it is beneficial to stay ahead of thirst and maintain weight during exercise.[38]

In warm or humid weather, or during heavy exertion, water loss can increase markedly, because humans have a large and widely variable capacity for sweating. Whole-body sweat losses in men can exceed 2 L/h during competitive sport, with rates of 3–4 L/h observed during short-duration, high-intensity exercise in the heat.[39] When such large amounts of water are being lost through perspiration, electrolytes, especially sodium, are also being lost.[40]

In most athletes exercising and sweating for 4–5 hours with a sweat sodium concentration of less than 50 mmol/L, the total sodium lost is less than 10% of total body stores (total stores are approximately 2,500 mmol, or 58 g for a 70-kg person).[41] These losses appear to be well tolerated by most people. The inclusion of sodium in fluid replacement drinks has some theoretical benefits[41] and poses little or no risk, so long as these fluids are hypotonic (since the mainstay of dehydration prevention is the replacement of free water losses).

Treatment

[edit]The most effective treatment for minor dehydration is widely considered to be drinking water and reducing fluid loss. Plain water restores only the volume of the blood plasma, inhibiting the thirst mechanism before solute levels can be replenished.[42] Consumption of solid foods can also contribute to hydration. It is estimated approximately 22% of American water intake comes from food.[43] Urine concentration and frequency will return to normal as dehydration resolves.[44]

In some cases, correction of a dehydrated state is accomplished by the replenishment of necessary water and electrolytes (through oral rehydration therapy, or fluid replacement by intravenous therapy). As oral rehydration is less painful, non-invasive, inexpensive, and easier to provide, it is the treatment of choice for mild dehydration.[45] Solutions used for intravenous rehydration may be isotonic, hypertonic, or hypotonic depending on the cause of dehydration as well as the sodium concentration in the blood.[46] Pure water injected into the veins will cause the breakdown (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes).[47]

When fresh water is unavailable (e.g. at sea or in a desert), seawater or drinks with significant alcohol concentration will worsen dehydration. Urine contains a lower solute concentration than seawater; this requires the kidneys to create more urine to remove the excess salt, causing more water to be lost than was consumed from seawater.[48]

For severe cases of dehydration where fainting, unconsciousness, or other severely inhibiting symptoms are present (the patient is incapable of standing upright or thinking clearly), emergency attention is required. Fluids containing a proper balance of replacement electrolytes are given orally or intravenously with continuing assessment of electrolyte status; complete resolution is normal in all but the most extreme cases.[49][50]

Prognosis

[edit]The prognosis for dehydration depends on the cause and extent of dehydration. Mild dehydration normally resolves with oral hydration. Chronic dehydration, such as from physically demanding jobs or decreased thirst, can lead to chronic kidney disease.[51] Elderly people with dehydration are at higher risk of confusion, urinary tract infections, falls, and even delayed wound healing.[52] In children with mild to moderate dehydration, oral hydration is adequate for a full recovery.[53]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Dehydration - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ El-Sharkawy AM, Sahota O, Lobo DN (September 2015). "Acute and chronic effects of hydration status on health". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (Suppl 2): 97–109. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv038. PMID 26290295.

- ^ a b c Mange K, Matsuura D, Cizman B, Soto H, Ziyadeh FN, Goldfarb S, et al. (November 1997). "Language guiding therapy: the case of dehydration versus volume depletion". Annals of Internal Medicine. 127 (9): 848–853. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00020. PMID 9382413. S2CID 29854540.

- ^ Ashcroft F, Life Without Water in Life at the Extremes. Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000, 134-138.

- ^ Seal AD, Suh HG, Jansen LT, Summers LG, Kavouras SA (2019). "Hydration and Health". In Pounis G (ed.). Analysis in Nutrition Research. Elsevier. pp. 299–319. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814556-2.00011-7. ISBN 978-0-12-814556-2.

- ^ Clark WF, Sontrop JM, Huang SH, Moist L, Bouby N, Bankir L (2016). "Hydration and Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: A Critical Review of the Evidence". American Journal of Nephrology. 43 (4): 281–292. doi:10.1159/000445959. PMID 27161565.

- ^ The Handbook Of The SAS And Elite Forces. How The Professionals Fight And Win. Edited by Jon E. Lewis. p.426-Tactics And Techniques, Survival. Robinson Publishing Ltd 1997. ISBN 1-85487-675-9

- ^ Riebl SK, Davy BM (November 2013). "The Hydration Equation: Update on Water Balance and Cognitive Performance". ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal. 17 (6): 21–28. doi:10.1249/FIT.0b013e3182a9570f. PMC 4207053. PMID 25346594.

- ^ Hall H (August 17, 2020). "Are You Dehydrated?". Skeptical Inquirer. 4 (4).

- ^ a b c Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Attreed NJ, Campbell WW, Channell AM, Chassagne P, et al. (Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Group) (April 2015). "Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4) CD009647. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009647.pub2. hdl:2066/110560. PMC 7097739. PMID 25924806.

- ^ Paulis SJ, Everink IH, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C, Schols JM (August 1, 2018). "Prevalence and Risk Factors of Dehydration Among Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review". Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 19 (8): 646–657. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2018.05.009. ISSN 1525-8610. PMID 30056949.

- ^ Sawka MN, Montain SJ (August 1, 2000). "Fluid and electrolyte supplementation for exercise heat stress1234". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. NIH Workshop on the Role of Dietary Supplements for Physically Active People. 72 (2): 564S – 572S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.2.564S. ISSN 0002-9165.

- ^ Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS (June 9, 2004). "Is This Child Dehydrated?". JAMA. 291 (22): 2746–2754. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 15187057.

- ^ Research Io, Marriott BM, Carlson SJ (1996), "Fluid Metabolism at High Altitudes", Nutritional Needs In Cold And In High-Altitude Environments: Applications for Military Personnel in Field Operations, National Academies Press (US), retrieved November 15, 2024

- ^ Puga AM, Lopez-Oliva S, Trives C, Partearroyo T, Varela-Moreiras G (March 20, 2019). "Effects of Drugs and Excipients on Hydration Status". Nutrients. 11 (3): 669. doi:10.3390/nu11030669. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6470661. PMID 30897748.

- ^ Borra SI, Beredo R, Kleinfeld M (March 1995). "Hypernatremia in the aging: causes, manifestations, and outcome". Journal of the National Medical Association. 87 (3): 220–224. PMC 2607819. PMID 7731073.

- ^ Lindner G, Funk GC (April 2013). "Hypernatremia in critically ill patients". Journal of Critical Care. 28 (2): 216.e11–216.e20. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.001. PMID 22762930.

- ^ Sved A, Walsh D. "Fluid composition of the body 1.3".

- ^ a b Schoeller 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Kamel KS, Halperin ML (2017). Fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base physiology: a problem-based approach (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-35515-5.

- ^ a b Garden J, Parks R, Wigmore S (2023). Principles and Practice of Surgery (8th ed.). Elsevier Limited. pp. 32–55. ISBN 978-0-7020-8251-1.

- ^ White BA, Harrison JR, Mehlmann LM (2019). Endocrine and reproductive physiology. Mosby physiology series (5th ed.). St. Louis, MI: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-59573-5.

- ^ Webb AJ, Seisa MO, Nayfeh T, Wieruszewski PM, Nei SD, Smischney NJ (December 2020). "Vasopressin in vasoplegic shock: A systematic review". World Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 9 (5): 88–98. doi:10.5492/wjccm.v9.i5.88. PMC 7754532. PMID 33384951.

- ^ Dehydration at eMedicine

- ^ Bhave G, Neilson EG (August 2011). "Volume depletion versus dehydration: how understanding the difference can guide therapy". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 58 (2): 302–309. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.02.395. PMC 4096820. PMID 21705120.

- ^ "UOTW#59 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Huffman GB (September 15, 1999). "Establishing a Bedside Diagnosis of Hypovolemia". American Family Physician. 60 (4): 1220–1225.

- ^ Braun MM, Barstow CH, Pyzocha NJ (March 1, 2015). "Diagnosis and Management of Sodium Disorders: Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia". American Family Physician. 91 (5): 299–307. PMID 25822386.

- ^ Thomas J, Monaghan T (2014). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Examination and Practical Skills. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959397-2.

- ^ Hughes G (2021). A medication guide to internal medicine tests and procedures (First ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier, Inc. ISBN 978-0-323-79007-9.

- ^ Tietze KJ (2012), "Review of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests", Clinical Skills for Pharmacists, Elsevier, pp. 86–122, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07738-5.10005-5, ISBN 978-0-323-07738-5, retrieved November 6, 2024

- ^ Yun G, Baek SH, Kim S (May 1, 2023). "Evaluation and management of hypernatremia in adults: clinical perspectives". The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 38 (3): 290–302. doi:10.3904/kjim.2022.346. ISSN 1226-3303. PMC 10175862. PMID 36578134.

- ^ Mohamed MS, Martin A (May 2024). "Acute kidney injury in critical care". Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 25 (5): 308–315. doi:10.1016/j.mpaic.2024.03.008.

- ^ Amin R, Ahn SY, Moudgil A (2021), "Kidney and urinary tract disorders", Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Pediatric Disease, Elsevier, pp. 167–228, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-817962-8.00010-x, ISBN 978-0-12-817962-8, retrieved November 6, 2024

- ^ Institute of Medicine, Food Nutrition Board (June 18, 2005). Dietary Reference Intakes: Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate: Health and Medicine Division. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09169-5. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Armstrong LE, Johnson EC (December 5, 2018). "Water Intake, Water Balance, and the Elusive Daily Water Requirement". Nutrients. 10 (12): 1928. doi:10.3390/nu10121928. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6315424. PMID 30563134.

- ^ Yamada Y, Zhang X, Henderson ME, Sagayama H, Pontzer H, Watanabe D, et al. (November 2022). "Variation in human water turnover associated with environmental and lifestyle factors". Science. 378 (6622): 909–915. Bibcode:2022Sci...378..909I. doi:10.1126/science.abm8668. PMC 9764345. PMID 36423296.

- ^ Noakes TD (2010). "Is drinking to thirst optimum?". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 57 (Suppl 2): 9–17. doi:10.1159/000322697. PMID 21346332.

- ^ Taylor NA, Machado-Moreira CA (February 2013). "Regional variations in transepidermal water loss, eccrine sweat gland density, sweat secretion rates and electrolyte composition in resting and exercising humans". Extreme Physiology & Medicine. 2 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/2046-7648-2-4. PMC 3710196. PMID 23849497.

- ^ Baker LB (March 2017). "Sweating Rate and Sweat Sodium Concentration in Athletes: A Review of Methodology and Intra/Interindividual Variability". Sports Medicine. 47 (S1): 111–128. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0691-5. ISSN 0112-1642. PMC 5371639. PMID 28332116.

- ^ a b Coyle EF (January 2004). "Fluid and fuel intake during exercise". Journal of Sports Sciences. 22 (1): 39–55. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.321.6991. doi:10.1080/0264041031000140545. PMID 14971432. S2CID 14693195.

- ^ Murray R, Stofan J (2001). "Ch. 8: Formulating carbohydrate-electrolyte drinks for optimal efficacy". In Maughan RJ, Murray R (eds.). Sports Drinks: Basic Science and Practical Aspects. CRC Press. pp. 197–224. ISBN 978-0-8493-7008-3.

- ^ Popkin BM, D'Anci KE, Rosenberg IH (August 2010). "Water, hydration, and health: Nutrition Reviews©, Vol. 68, No. 8". Nutrition Reviews. 68 (8): 439–458. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x. PMC 2908954. PMID 20646222.

- ^ Ostermann M, Shaw AD, Joannidis M (January 1, 2023). "Management of oliguria". Intensive Care Medicine. 49 (1): 103–106. doi:10.1007/s00134-022-06909-5. ISSN 1432-1238. PMID 36266588.

- ^ Aghsaeifard Z, Heidari G, Alizadeh R (September 2022). "Understanding the use of oral rehydration therapy: A narrative review from clinical practice to main recommendations". Health Science Reports. 5 (5) e827. doi:10.1002/hsr2.827. ISSN 2398-8835. PMC 9464461. PMID 36110343.

- ^ Kim SW (2006). "Hypernatemia: Successful Treatment". Electrolytes & Blood Pressure. 4 (2): 66–71. doi:10.5049/EBP.2006.4.2.66. ISSN 1738-5997. PMC 3894528. PMID 24459489.

- ^ Tinawi M (April 21, 2021). "New Trends in the Utilization of Intravenous Fluids". Cureus. 13 (4) e14619. doi:10.7759/cureus.14619. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 8140055. PMID 34040918.

- ^ Hall JE, Hall ME, Guyton AC (2021). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (14th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-67280-1.

- ^ Gawronska J, Koyanagi A, López Sánchez GF, Veronese N, Ilie PC, Carrie A, et al. (December 31, 2022). "The Prevalence and Indications of Intravenous Rehydration Therapy in Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review". Epidemiologia. 4 (1): 18–32. doi:10.3390/epidemiologia4010002. ISSN 2673-3986. PMC 9844368. PMID 36648776.

- ^ Ellershaw JE, Sutcliffe JM, Saunders CM (April 1995). "Dehydration and the dying patient". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 10 (3): 192–197. doi:10.1016/0885-3924(94)00123-3. PMID 7629413.

- ^ El Khayat M, Halwani DA, Hneiny L, Alameddine I, Haidar MA, Habib RR (February 8, 2022). "Impacts of Climate Change and Heat Stress on Farmworkers' Health: A Scoping Review". Frontiers in Public Health. 10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.782811. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 8861180. PMID 35211437.

- ^ Bruno C, Collier A, Holyday M, Lambert K (October 18, 2021). "Interventions to Improve Hydration in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 13 (10): 3640. doi:10.3390/nu13103640. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 8537864. PMID 34684642.

- ^ Canavan A, Billy S Arant J (October 1, 2009). "Diagnosis and Management of Dehydration in Children". American Family Physician. 80 (7): 692–696. PMID 19817339.

Further reading

[edit]- Byock I (1995). "Patient refusal of nutrition and hydration: walking the ever-finer line". The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 12 (2): 8, 9–8, 13. doi:10.1177/104990919501200205. PMID 7605733. S2CID 46385519.

- Schoeller DA (2005). "Hydrometry". In Heymsfield S (ed.). Human Body Composition. Human Kinetics. ISBN 978-0-7360-4655-8. Retrieved January 24, 2025.

- Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS (June 2004). "Is this child dehydrated?". JAMA. 291 (22): 2746–2754. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746. PMID 15187057.

External links

[edit]Dehydration

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Types

Definition

Dehydration refers to a state of negative fluid balance resulting from water loss in excess of intake, with or without electrolyte disturbances, leading to decreased total body water. While the term is sometimes used strictly to denote a free water deficit causing hypertonicity (often with hypernatremia), it is commonly applied more broadly in clinical practice to include various types of fluid deficits that disrupt physiological functions.[3][7] This occurs when fluid losses exceed intake, potentially reducing total body water and altering plasma osmolality, which triggers compensatory mechanisms such as thirst and antidiuretic hormone release to restore homeostasis.[8] In a typical adult, total body water accounts for approximately 60% of body weight, distributed such that two-thirds resides in the intracellular compartment and one-third in the extracellular space, including plasma and interstitial fluid.[9][10] This composition is essential for maintaining cellular integrity, electrolyte balance, and organ function, and any significant deviation, as in dehydration, impairs these processes.[3] Dehydration must be differentiated from volume depletion, as the former specifically denotes a deficit of free water without proportional electrolyte loss, leading to hypertonicity, whereas the latter involves overall reduction in extracellular fluid volume from combined water and solute losses.[11] The term "dehydration" originates from the Latin prefix "de-" (removal) combined with "hydrate," derived from the Greek "hydor" (water), with its first recorded medical use in the mid-19th century.[12] The underlying concept of pathological fluid loss, however, was recognized in ancient medicine, notably in the works of Hippocrates around 400 BCE, who described age-related declines in body water as contributing to disease.[13]Types

Dehydration is classified into three primary types based on serum sodium concentration, which indicates the relative proportions of water and electrolyte losses: isotonic, hypertonic (also known as hypernatremic), and hypotonic (also known as hyponatremic).[14] This classification helps differentiate clinical management due to varying impacts on fluid balance and cellular function.[3] Isotonic dehydration arises from proportionate losses of water and sodium, preserving normal serum sodium levels between 135 and 145 mEq/L.[15] It represents the most frequent type, commonly associated with conditions involving balanced fluid depletion such as gastroenteritis.[14] Hypertonic dehydration results from excessive water loss compared to sodium, elevating serum sodium above 145 mEq/L.[3] This hyperosmolar state prompts osmotic water shifts out of cells, causing cellular shrinkage and potential neurological risks.[16] Hypotonic dehydration occurs when sodium loss exceeds water loss, lowering serum sodium below 135 mEq/L.[15] Consequently, osmotic gradients drive water into cells, leading to cellular swelling.[14] Among these, hypertonic dehydration poses the greatest risk in children, with studies reporting its occurrence in approximately 1-2% of pediatric dehydration cases.[17]Causes and Risk Factors

Causes

Dehydration primarily arises from an imbalance where fluid losses exceed intake, leading to net water and electrolyte deficits. This can occur through various pathways, including excessive output from the body or insufficient replacement.[3] Gastrointestinal causes are among the most common, particularly vomiting and diarrhea, which rapidly deplete fluids and electrolytes. Infections such as rotavirus are a leading etiology in children, causing severe watery diarrhea that results in dehydration; prior to widespread vaccination, rotavirus led to approximately 2.7 million infections annually in the United States, with many cases progressing to hospitalization due to fluid loss.[18] Other viral, bacterial, or parasitic gastroenteritis can similarly trigger profuse losses, accounting for a significant portion of dehydration episodes in pediatric populations.[19] Inadequate fluid intake contributes when thirst mechanisms are impaired or access to water is limited. Infants and young children often have underdeveloped thirst responses and higher fluid requirements relative to body size, while older adults may experience blunted thirst sensation due to age-related physiological changes, increasing vulnerability in both groups.[20] Environmental factors, such as prolonged heat exposure, can exacerbate this by heightening insensible losses without compensatory drinking, particularly in situations where fluids are unavailable.[2] Increased extrarenal or renal losses also drive dehydration through mechanisms like excessive sweating during intense physical activity, such as high-intensity cardio, or hot climates, which can exceed several liters per hour in extreme conditions and lead to significant fluid and electrolyte (e.g., sodium, potassium) losses; even mild dehydration from this can impair cognitive function, causing brain fog due to reduced blood flow and nutrient delivery to the brain.[21][22][4] Fever elevates insensible fluid loss via perspiration and tachypnea, while polyuria from conditions such as diabetes insipidus—characterized by impaired antidiuretic hormone action—leads to profound urinary water wasting, often surpassing 3-20 liters daily.[23] These losses are particularly risky in vulnerable populations like the elderly or those with chronic illnesses.[24] Iatrogenic causes stem from medical interventions that promote fluid elimination, including overuse of diuretics, which inhibit renal water reabsorption and can induce hypovolemia, or excessive laxative use, leading to osmotic diarrhea and electrolyte shifts.[25] Such agents are commonly prescribed for hypertension, edema, or constipation but require careful monitoring to prevent unintended dehydration.[26]Risk Factors

Infants and young children are particularly vulnerable to dehydration due to their physiological characteristics, including a higher surface area-to-volume ratio that leads to greater fluid loss through the skin and immature kidneys with limited ability to concentrate urine and regulate fluid balance.[27][28] Similarly, older adults face elevated risks from age-related changes such as diminished thirst sensation, reduced total body water reserves (typically 50–60% of body weight), and diminished renal concentrating ability, which impair recognition of fluid needs, reduce reserves against losses, and hinder water conservation. Additional contributing factors include medications such as diuretics, illnesses causing fluid loss (e.g., diarrhea, fever), mobility or cognitive impairments limiting self-care and fluid access, and limited access to water.[20][29][2][3] Certain medical conditions heighten dehydration susceptibility by disrupting fluid homeostasis; for instance, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus promotes osmotic diuresis, where excess glucose in the urine draws out water, while chronic renal disease impairs the kidneys' water conservation mechanisms, and infections—particularly those causing fever, vomiting, or diarrhea—accelerate fluid loss.[2][14] Environmental factors also play a significant role, with exposure to hot climates increasing sweat production and evaporative losses that outpace fluid intake, and high altitudes exacerbating dehydration through heightened respiratory water loss from increased ventilation rates in low-oxygen conditions.[30][31] Situational environmental factors, such as exposure to dry cabin air during long-haul flights, can increase insensible fluid losses and, when combined with disrupted routines that limit fluid intake, lead to dehydration resulting in concentrated urine that may irritate the bladder and cause pelvic discomfort.[32][33] Among athletes, particularly those in endurance events like marathons, dehydration affects approximately 21% of participants across various race distances, underscoring the compounded risks from prolonged exertion in warm environments.[34] Socioeconomic challenges, such as limited access to clean water in developing regions, further predispose vulnerable populations to dehydration, especially children, where diarrheal diseases linked to poor sanitation contribute to about 9% of global under-five mortality according to UNICEF data.[35] These risks often intersect with common precipitants like diarrhea in children, amplifying overall vulnerability.[14]Pathophysiology

Mechanism

Dehydration disrupts homeostasis primarily through osmotic, hormonal, and cardiovascular mechanisms that alter fluid distribution and organ function. Dehydration is classified into three types based on the relative loss of water and electrolytes: hypertonic (water loss exceeds sodium loss), isotonic (proportional loss of water and sodium), and hypotonic (sodium loss exceeds water loss).[3] In hypertonic dehydration, elevated extracellular osmolality due to water loss exceeding sodium loss creates a hyperosmolar environment, prompting water to shift from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment across cell membranes.[3] This osmotic gradient leads to cellular dehydration and shrinkage, particularly in the brain, where it can cause neurological effects such as altered mental status and seizures by compressing neural tissues against the skull.[3] During exercise, dehydration impairs cognitive function through reduced blood volume, which decreases cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain, alongside disruptions in electrolyte balance and temporary brain tissue shrinkage that increase neuronal activation. This results in symptoms including mental fog, forgetfulness, fatigue, headache, or irritability, with effects more noticeable in hot conditions or intense sessions.[36][37] In isotonic dehydration, equal losses of water and sodium lead to hypovolemia without significant changes in serum osmolality. This results in reduced circulating volume, impairing tissue perfusion and activating compensatory mechanisms to maintain blood pressure, but without the osmotic shifts seen in hypertonic cases.[3] In hypotonic dehydration, greater sodium loss relative to water causes hyponatremia, leading to water shifting into cells and causing cellular swelling, particularly cerebral edema, which can manifest as headaches, nausea, and in severe cases, seizures or coma.[3] To counteract fluid loss, the body activates hormonal responses, notably the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Low effective circulating volume in dehydration stimulates juxtaglomerular cells in the kidneys to release renin, which converts angiotensinogen to angiotensin I and subsequently to angiotensin II via angiotensin-converting enzyme.[38] Angiotensin II promotes vasoconstriction and stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete aldosterone, which enhances sodium reabsorption in the distal tubules and collecting ducts of the kidneys, thereby promoting water retention to restore volume.[38] Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release from the posterior pituitary further contributes by increasing water permeability in the renal collecting ducts.[39] In addition, ADH (also known as vasopressin) exerts vasoconstrictive effects at higher concentrations, narrowing blood vessels to increase peripheral vascular resistance and thereby helping to maintain or elevate blood pressure in response to reduced blood volume. This response can lead to increased blood pressure and greater cardiac workload as the heart contracts against higher resistance. However, in some cases, particularly severe dehydration, the reduction in blood volume can cause low blood pressure due to hypovolemia when compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed. Chronic hypohydration has also been proposed as a risk factor for the development of hypertension.[40][1] At the systemic level, dehydration reduces plasma volume (hypovolemia), decreasing venous return and cardiac preload, which impairs stroke volume and cardiac output. The body compensates with tachycardia and vasoconstriction to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure, but in moderate to severe cases, this can progress to hypotension as compensatory mechanisms fail, potentially leading to tissue hypoperfusion. In severe dehydration, the resulting hypovolemia impairs oxygen delivery to tissues, prompting compensatory respiratory responses such as tachypnea (rapid breathing), which may manifest as shortness of breath, respiratory distress, or labored breathing. These cardiovascular changes exacerbate the overall stress on homeostasis, prioritizing vital organ perfusion.[41][42] The severity of hypertonic dehydration can be quantified using the free water deficit equation, which estimates the volume of water needed to correct hypernatremia: This formula assumes total body water as approximately 60% of body weight in adults (adjusted to 50% for females or elderly), with 140 mEq/L as the normal serum sodium concentration, providing a clinical tool to guide rehydration therapy.[43]Stages of Progression

Dehydration progresses through distinct stages defined by the percentage of body weight lost due to fluid deficit, each characterized by escalating physiological disruptions that impair homeostasis if untreated. These stages are typically classified as mild, moderate, and severe, with clinical assessment relying on weight loss estimates, vital signs, and symptoms to guide intervention.[14] In the mild stage, fluid loss ranges from 1% to 5% of body weight, often manifesting as subtle thirst and dry mucous membranes, with minimal impact on vital signs but early activation of compensatory mechanisms like the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) to conserve water. At this level, urine output remains relatively normal, though slightly concentrated, and individuals may experience mild fatigue without significant hemodynamic changes. Prompt oral rehydration usually reverses this stage effectively.[44][14][45] The moderate stage involves 6% to 9% body weight loss, leading to more pronounced effects such as sunken eyes, reduced skin turgor, and decreased urine output below 0.5 mL/kg/hour, indicating oliguria and early renal strain. Tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension emerge as the body struggles to maintain perfusion, with dry mucous membranes becoming more evident and potential for electrolyte imbalances. This stage requires closer monitoring and often intravenous fluids to prevent further deterioration.[44][14][45] Severe dehydration occurs with greater than 10% body weight loss, resulting in critical physiological impacts including lethargy, hypovolemic shock, and multi-organ failure due to profound hypovolemia and tissue hypoperfusion. Symptoms intensify to include confusion, rapid thready pulse, and anuria, with mortality risk exceeding 20% without immediate intervention, particularly in vulnerable populations like the elderly or infants. Hospitalization with aggressive fluid resuscitation is essential to avert death.[44][3][46] The timeline of progression varies by context: acute dehydration can advance from mild to severe within hours during extreme conditions like heatstroke, driven by rapid insensible losses, whereas chronic forms, such as in malnutrition, develop gradually over days through sustained inadequate intake. Without any water intake, humans can typically survive for about 3–7 days, depending on factors like body fat reserves, environment, activity level, and health. Metabolic water from fat breakdown helps extend this slightly by providing ~1 liter per day if burning significant fat, but it only partially replaces losses from urine, breath, sweat, and feces.[47][14][48][49][50]Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Dehydration manifests through a variety of subjective and observable indicators that reflect the body's response to fluid loss. Common general symptoms include extreme thirst, fatigue, dry mouth and lips, and dry skin with decreased turgor (where pinched skin does not quickly return to normal position), which arise as the body signals the need for fluid replenishment and compensates for reduced hydration.[2] In infants and young children, dehydration can progress rapidly due to higher relative fluid requirements and limited reserves. Specific signs include sunken fontanelle (if still open), no tears when crying, dry mouth and mucous membranes, sunken eyes, fewer or no wet diapers (typically fewer than six per day in young infants), lethargy, restlessness, irritability, and faster or deeper breathing. In newborns, no wet diaper for 6 hours or more requires prompt medical evaluation. In children around 1 year of age, these signs are particularly indicative. Conversely, signs of sufficient hydration in a 6-month-old baby include at least six wet diapers per day and an alert, happy demeanor.[2][3][51] Older adults are particularly vulnerable to dehydration due to age-related physiological changes, including reduced thirst sensation, lower total body water reserves, and diminished renal concentrating ability, as well as contributing factors such as medications (e.g., diuretics), chronic illnesses, mobility or cognitive impairments, and limited access to fluids. In this population, thirst is often absent or unreliable as an early indicator. Common signs include dry mouth, dark-colored urine, reduced urination, tiredness, dizziness, confusion, sunken eyes or cheeks, and poor skin turgor. Atypical presentations are frequent, with older adults more likely to exhibit confusion, delirium, or falls rather than classic symptoms; severe cases may involve rapid heartbeat (tachycardia) or shock.[2][3] Neurological signs often involve headache, confusion, and, particularly in children, irritability, as diminished fluid volume affects brain function and electrolyte balance. Even mild dehydration, such as that resulting from high-intensity cardio exercise through significant sweating and loss of fluids and electrolytes (e.g., sodium, potassium), can impair concentration and cause brain fog, mental fog, forgetfulness, fatigue, headache, or irritability due to the brain's sensitivity to hydration status; these cognitive impairments are more noticeable in hot conditions or during intense exercise sessions.[52][22][2][53][54][36][55] Cardiovascular effects include an increased heart rate, or tachycardia, to maintain cardiac output amid hypovolemia, and orthostatic hypotension, which causes dizziness upon standing due to decreased blood volume.[3][56] Urinary symptoms feature dark-colored urine and oliguria, indicating concentrated urine and reduced output from impaired kidney perfusion; this concentrated urine can irritate the bladder and urethra, leading to discomfort or pain in the pelvic or genital region. Such symptoms may be exacerbated by factors like long flights with dry cabin air and disrupted routines.[2][3][54][57] Severe dehydration can develop rapidly in cases of persistent diarrhea and vomiting lasting more than three days, especially when accompanied by dehydration signs such as dry mouth and lips, very little or dark urine, extreme thirst, dizziness, fatigue, rapid pulse, and decreased skin turgor. In children, severe signs indicating a medical emergency include extreme lethargy or unresponsiveness, unconsciousness, cool hands and feet, confusion, rapid breathing, no urine for many hours, or symptoms of hypovolemic shock (restlessness, chills, sweating, apathy). In Germany, these severe signs require immediately calling emergency services at 112. For mild symptoms or ongoing fluid loss (e.g., from diarrhea/vomiting), consult a pediatrician promptly. Emergency care should be sought promptly if there is inability to retain fluids, no urination for more than eight hours, confusion, rapid breathing or shortness of breath, or fainting, as these indicate severe dehydration that can lead to life-threatening complications if not addressed urgently. Shortness of breath or respiratory distress in severe cases arises from reduced blood volume and impaired oxygen delivery, prompting the body to compensate with rapid or deep breathing.[2][3][58][51] These symptoms tend to intensify in moderate to severe stages of dehydration, prompting urgent attention to prevent further progression.[2]Complications

Severe dehydration can precipitate acute kidney injury (AKI) through renal hypoperfusion, where reduced blood volume impairs glomerular filtration and leads to a rapid rise in serum creatinine levels by more than 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours.[59] This prerenal form of AKI is reversible if addressed promptly but underscores the kidneys' vulnerability to fluid deficits.[60] Dehydration disrupts electrolyte homeostasis, potentially causing imbalances such as hyponatremia, which lowers serum sodium and draws water into brain cells, resulting in cerebral edema and seizures.[3] Hypotonic dehydration exacerbates this risk by disproportionately losing solutes relative to water, elevating intracranial pressure and the potential for neurological complications like brain herniation.[3] In environments of extreme heat, dehydration impairs thermoregulation, contributing to heatstroke characterized by a core body temperature exceeding 40°C and central nervous system dysfunction. This condition carries a high mortality rate, reaching up to 50% in cases among the elderly due to their diminished physiological reserves.[61] Recent global data indicate that heat-related mortality among older adults has risen significantly, with an 85% increase for those over 65 between 2000–2004 and 2017–2021.[62] Recurrent episodes of dehydration have been linked to long-term chronic renal damage, with epidemiological studies indicating an elevated risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression in affected populations, such as agricultural workers exposed to repeated heat stress.[63] For instance, research on Mesoamerican nephropathy highlights how ongoing dehydration accelerates renal injury through mechanisms like hyperuricemia and glomerular hyperfiltration.[64]Diagnosis

Medical History and Physical Examination

The medical history for suspected dehydration begins with a detailed assessment of fluid balance to identify imbalances and underlying causes. Clinicians evaluate recent fluid intake, including oral consumption and any intravenous fluids, alongside output such as urine volume, stool consistency, and episodes of vomiting or diarrhea, noting their onset and duration to quantify potential losses.[3] Medication history is reviewed, focusing on agents like diuretics, laxatives, or antihypertensives that may promote fluid depletion.[5] Patients often report associated symptoms, such as intense thirst, to guide the evaluation.[14] Physical examination provides bedside clues to dehydration severity through non-invasive checks of hydration status and perfusion. Vital signs are monitored for tachycardia (elevated pulse rate) and hypotension, particularly orthostatic changes upon standing, reflecting the body's compensatory response to volume deficit.[3] Skin turgor is assessed by gently pinching the skin over the abdomen or forearm; persistence of the "tent" for more than 2 seconds indicates moderate to severe dehydration due to tissue desiccation.[3] Capillary refill time, measured by blanching the nail bed and observing return of color, exceeding 2 seconds signals impaired peripheral perfusion from hypovolemia.[3] Acute weight loss equaling or exceeding 2% of baseline body weight further corroborates fluid deficit.[3] In special populations like infants and young children, additional targeted assessments enhance accuracy. A sunken anterior fontanelle, observed when the infant is upright and calm, serves as an early indicator of dehydration, resulting from reduced intracranial fluid volume.[65] These findings, combined with history, allow clinicians to stratify dehydration risk without relying on laboratory confirmation.[5]Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory and diagnostic tests play a crucial role in confirming dehydration, assessing its severity, and distinguishing between types such as hypotonic, isotonic, or hypertonic based on electrolyte imbalances. These tests provide objective biochemical evidence that complements clinical findings, particularly in cases where physical examination is inconclusive. Blood and urine analyses are the primary modalities, with additional imaging reserved for severe or complicated presentations. Blood tests are essential for evaluating electrolyte status and renal function. Serum electrolytes, particularly sodium and potassium, help classify dehydration type; hypernatremia (sodium >145 mEq/L) indicates water-loss dehydration, while hyponatremia (sodium <135 mEq/L) suggests sodium-loss dehydration, and potassium levels may be elevated due to reduced renal excretion in hypovolemic states. The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to creatinine ratio is a key marker, with a ratio greater than 20:1 signaling prerenal azotemia from hypoperfusion and volume depletion. Additionally, elevated hematocrit levels, often above 50% in adults, reflect hemoconcentration due to reduced plasma volume. Urine analysis offers insights into renal concentrating ability and hydration status. Urine specific gravity greater than 1.020 indicates concentrated urine consistent with dehydration, as the kidneys conserve water. Urine osmolality exceeding 700 mOsm/kg further supports this, with values typically three to four times plasma osmolality (around 280-300 mOsm/kg) in dehydrated states, confirming intact renal response to volume depletion.[3] In severe cases, imaging such as renal ultrasound may be employed to evaluate perfusion, particularly if acute kidney injury is suspected from prolonged hypovolemia; Doppler assessment can reveal reduced renal blood flow velocities. For pediatric patients, dehydration is classified based on serum sodium levels as hypotonic if <135 mmol/L, isotonic if 135-145 mmol/L, and hypertonic if >145 mmol/L, guiding fluid therapy to prevent complications like cerebral edema.Prevention and Management

Prevention Strategies

Preventing dehydration involves adopting evidence-based hydration practices tailored to daily needs and environmental factors, particularly for vulnerable populations such as infants, children, and the elderly.[66] General hydration guidelines recommend that adults consume approximately 2.7 to 3.7 liters of fluids per day, depending on factors like age, sex, and body size, with water as the primary source.[6] For individuals engaging in physical activity, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) advises additional intake of about 0.4 to 0.8 liters per hour of exercise to replace sweat losses and maintain hydration.[67] These recommendations emphasize proactive fluid consumption rather than waiting for thirst, as delayed intake can lead to deficits.[68] When ill, particularly with conditions such as fever, vomiting, or diarrhea, the top priority regarding fluids is hydration to prevent dehydration. It is recommended to drink plenty of fluids, including water, broths, herbal teas, or electrolyte drinks.[69][6] In public health contexts, especially in areas prone to diarrheal diseases, the promotion of oral rehydration solutions (ORS) has proven effective in averting dehydration. The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses ORS as a cornerstone intervention, consisting of a precise mix of water, salts, and sugars, which has contributed to a substantial decline in global diarrhea-related mortality, from approximately 2.3 million deaths annually in 2000 to about 1.2 million as of 2021.[70] This reduction, exceeding 50% since 2000, underscores the impact of widespread ORS adoption in low-resource settings through community distribution and education programs.[71] Educational initiatives play a crucial role in prevention by raising awareness among at-risk groups. For the elderly, dehydration is common due to age-related physiological changes including blunted thirst sensation, reduced body water reserves, diminished renal concentrating ability, and additional factors such as medications (e.g., diuretics), chronic illnesses, mobility or cognitive impairments, and limited access to fluids. Prevention strategies include encouraging regular fluid intake of approximately 1.6–2.0 liters per day from preferred beverages (adjusted for individual needs, with higher amounts during illness, hot weather, or excessive losses), consumed in small, frequent sips to counteract reduced thirst perception; offering a variety of hydrating drinks and water-rich foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, soups); monitoring fluid intake and output; providing easy access to fluids with assistance for those with physical or cognitive limitations; and avoiding beverages that may contribute to dehydration, such as those high in caffeine or sugar.[72][2][66] In children, school-based hydration education encourages carrying water bottles and consuming 1 to 2 liters daily, integrating lessons on environmental cues like heat to foster lifelong habits.[73] These targeted efforts, often delivered through healthcare providers and community workshops, enhance self-monitoring and family involvement.[74] Environmental strategies ensure access to hydration in high-risk settings, such as workplaces exposed to heat. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires employers to provide potable water and encourage workers to drink at least 8 ounces every 20 minutes during hot conditions, alongside mandatory rest breaks to prevent heat-related dehydration.[75] In regions with specific standards, like California, employers must supply sufficient cool water—typically one quart per employee per hour—when temperatures exceed 80°F, combined with shaded areas for recovery.[76] These measures, enforced through training and monitoring, mitigate occupational risks effectively.[77]Treatment Approaches

Treatment of dehydration primarily involves restoring fluid and electrolyte balance, with approaches tailored to the severity and underlying type of dehydration, such as isotonic, hypotonic, or hypertonic variants that guide fluid selection. For mild to moderate cases, oral rehydration therapy (ORT) using the World Health Organization's low-osmolarity oral rehydration solution (ORS) is the first-line intervention, consisting of 2.6 g sodium chloride, 2.9 g trisodium citrate dihydrate, 1.5 g potassium chloride, and 13.5 g glucose per liter of water.[78] This formulation facilitates sodium and glucose absorption in the intestines, effectively rehydrating patients with a success rate of approximately 90% in mild to moderate dehydration from conditions like gastroenteritis.[79] Patients are typically administered 50-100 mL/kg over 4 hours, followed by maintenance fluids to replace ongoing losses.[80] In older adults, mild dehydration is typically managed with oral rehydration using water or electrolyte-containing solutions, while severe dehydration requires hospital admission for intravenous fluid administration. Treatment should address underlying causes (e.g., medication adjustments, treatment of precipitating illnesses), with close monitoring of electrolytes and renal function. An interprofessional approach involving nurses, physicians, and other healthcare professionals is recommended to prevent complications including falls, acute kidney injury, and cognitive decline.[5][20] Patients experiencing diarrhea and vomiting lasting more than 3 days accompanied by dehydration signs—including dry mouth and lips, minimal or dark urine, extreme thirst, dizziness, fatigue, rapid pulse, or reduced skin elasticity—should seek immediate medical attention due to the risk of severe dehydration. In older adults, thirst may be blunted or absent, and dehydration may present atypically with confusion, delirium, lethargy, weakness, or falls. In infants and young children (e.g., 1-year-olds), specific signs include sunken fontanelle (if still open), no tears when crying, dry mouth and mucous membranes, fewer or no wet diapers, sunken eyes, lethargy, restlessness, irritability, and faster or deeper breathing.[81][82] For mild symptoms or ongoing fluid loss (e.g., from diarrhea/vomiting) in babies, prompt consultation with a pediatrician is recommended. Severe signs—such as extreme lethargy/unresponsiveness, unconsciousness, cool hands and feet, confusion, rapid breathing, no urine for many hours, or hypovolemic shock symptoms (restlessness, chills, sweating, apathy)—constitute a medical emergency (Notfall) in Germany requiring immediate call to emergency services at 112. Immediate emergency hospital (emergency department) care is required if there is inability to retain fluids, no urination for more than 8 hours, confusion, rapid breathing, or fainting. Prolonged cases generally require medical evaluation, with severe dehydration necessitating emergency intervention.[5] In severe dehydration or when oral intake is not feasible due to vomiting or shock, intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation is essential. Isotonic crystalloids, such as 0.9% normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution, are administered initially at 20 mL/kg boluses to address hypovolemic shock, with ongoing replacement based on estimated deficits.[83] For hypernatremic (hypertonic) dehydration, correction must be gradual using hypotonic fluids to lower serum sodium at a rate not exceeding 0.5 mEq/L per hour, preventing cerebral edema from rapid osmotic shifts.[84] Adjunctive therapies, such as antiemetics like ondansetron, may be used to control vomiting and facilitate ORT in affected patients.[85] Throughout treatment, close monitoring is critical to assess response and prevent over- or under-correction. This includes hourly evaluation of urine output (targeting at least 1 mL/kg/hour), serial serum electrolyte measurements, vital signs, and weight changes to guide fluid adjustments.[80] In special cases involving severe renal complications, such as acute kidney injury with oliguria secondary to profound dehydration, hemodialysis or other renal replacement therapy may be required to manage fluid overload and electrolyte derangements.[86]Prognosis and Epidemiology

Prognosis

The prognosis for mild dehydration is generally excellent, with full recovery typically occurring within 24 to 48 hours through oral rehydration therapy, and mortality rates below 1%.[87][3] In contrast, severe dehydration carries a higher risk, particularly in vulnerable populations; for children with severe dehydration from diarrheal diseases, case fatality rates are approximately 13% without adequate intervention.[88] Adults with severe cases fare better with prompt intravenous fluid administration, often achieving favorable outcomes if treated early to prevent hypovolemic shock.[3] Several factors influence outcomes in dehydration cases. Age plays a critical role, with elderly individuals experiencing complication rates exceeding 20% due to reduced physiological reserves and impaired thirst mechanisms.[89] Comorbidities such as heart failure further worsen prognosis by exacerbating fluid imbalances and increasing the risk of organ dysfunction.[3] Chronic dehydration may increase the risk of developing hypertension.[40] Complications like acute kidney injury can prolong recovery and elevate mortality if not addressed promptly.[3] The introduction of oral rehydration salts (ORS) has markedly improved global prognosis for dehydration, especially in children with diarrheal illnesses, reducing annual under-5 deaths from approximately 4.6 million in 1980 to about 1.5 million by the early 2000s, with further declines to around 340,000 by 2021.[90][91] This decline reflects widespread adoption of ORS, which has decreased mortality by up to 93% in community settings.[92]Epidemiology

Dehydration imposes a substantial global health burden, with diarrheal diseases leading to severe dehydration responsible for an estimated 1.2 million deaths globally in 2021 (95% uncertainty interval 0.79–1.62 million), the majority occurring in children under 5 years in low- and middle-income countries.[91] This disproportionate impact stems from limited access to clean water, sanitation, and timely medical interventions in these regions.[93] Regional disparities highlight the uneven distribution of this burden, with sub-Saharan Africa experiencing particularly high rates where diarrhea-related dehydration accounts for approximately 25% of all child deaths under 5 years.[94] In contrast, developed nations report far lower mortality, with dehydration contributing to less than 0.1% of child deaths due to advanced healthcare infrastructure and preventive measures.[95] Over recent decades, global trends indicate a decline in dehydration incidence and related mortality, largely attributable to widespread vaccination programs; the rotavirus vaccine, introduced in 2006, has reduced severe diarrhea cases by about 40% in vaccinated populations.[96] Demographically, vulnerability varies by age group, with children and the elderly facing heightened risks—U.S. studies show a prevalence of approximately 30–40% among elderly residents in nursing homes, often linked to comorbidities and reduced thirst perception.[97]References

- https://wikem.org/wiki/Reduced-osmolarity_oral_rehydration_solution