Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

1954 Geneva Conference

View on Wikipedia

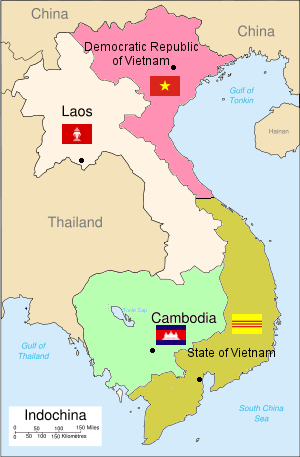

The Geneva Conference was intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War and the First Indochina War and involved several nations. It took place in Geneva, Switzerland, from 26 April to 21 July 1954.[1] The part of the conference on the Korean question ended without adopting any declarations or proposals and so is generally considered less relevant. On the other hand, the Geneva Accords that dealt with the dismantling of French Indochina proved to have long-lasting repercussions.

Diplomats from South Korea, North Korea, China, the Soviet Union, and the United States dealt with the Korean side of the conference. On the Indochina issue, the conference involved representatives from France, China, the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the State of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.[2] Three binding ceasefire agreements about Indochina ended hostilities in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The Pathet Lao were confined to two provinces in northern Laos, and Khmer Issarak forces disbanded. Vietnam was provisionally partitioned at the 17th parallel, with troops and personnel of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam regrouping to the North, and those of the French Union (including the State of Vietnam) regrouping to the South. Alongside them, a non‑legally binding Final Declaration called for international supervision (via the International Control Commission), prohibited the introduction of foreign troops and bases in Vietnam, affirmed that the 17th parallel was only a provisional demarcation, and scheduled national elections for 1956.[1] Worsening relations between the North and South would eventually lead to the Vietnam War.

Background

[edit]On 18 February 1954, at the Berlin Conference, participants agreed that "the problem of restoring peace in Indochina will also be discussed at the Conference [on the Korean question] to which representatives of the United States, France, the United Kingdom, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Chinese People's Republic and other interested states will be invited."[3]: 436

The conference was held at the Palace of Nations in Geneva, commencing on 26 April 1954. The first agenda item was the Korean question to be followed by Indochina.[3]: 549

People's Republic of China

[edit]"China's belligerent policies in Korea and Indochina", coupled with their increasing diplomatic closeness to the Soviet Union, would actively make China's international presence rather isolated.[4]: 94 Fearing further isolation from the emerging de-colonized world, and also a possible American intervention into Indochina, the PRC's Foreign Affairs Ministry (led by Zhou Enlai) would go into the conference with the key objective of breaking the US embargo of China and preventing American military intervention. Moreover, Zhou also stressed adopting a more "realistic" and moderate attitude which could deliver tangible results to the Indochina problem.[4]: 96–97

Korea

[edit]The armistice signed at the end of the Korean War required a political conference within three months—a timeline which was not met—"to settle through negotiation the questions of the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Korea, the peaceful settlement of the Korean question, etc."[5]

Indochina

[edit]As decolonization took place in Asia, France had to relinquish its power over Indochina (Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam). While Laos and Cambodia were both given independence, France chose to stay in Vietnam. This ended with a war between French troops and the Vietnamese nationalists led by Ho Chi Minh. The latter's army, the Viet Minh, fought a guerrilla war against the French, who relied on Western technology. After a series of offensives, gradually whittling away at French held territory between 1950 and 1954, hostilities culminated in a decisive defeat for the French at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. This resulted in a French withdrawal and the Geneva conference.

It was decided that Vietnam would be divided at the 17th parallel until 1956 when democratic elections would be held under international supervision and auspices. All parties involved agreed to this (Ho Chi Minh had strong support in the north, which was more populous than the south, and was thus confident that he would win an election), except for the U.S., which, in the spirit of the Cold War, feared seeing communism spreading in a domino effect throughout Asia as written in a National Intelligence Estimate dated 3 August 1954.[6]

Korea

[edit]The South Korean representative proposed that the South Korean government was the only legal government in Korea, that UN-supervised elections should be held in the North, that Chinese forces should withdraw, and that UN forces, a belligerent party in the war, should remain as a police force. The North Korean representative suggested that elections be held throughout all of Korea, that all foreign forces leave beforehand, that the elections be run by an all-Korean Commission to be made up of equal parts from North and South Korea, and to increase general relations economically and culturally between the North and the South.[7]

The Chinese delegation proposed an amendment to have a group of 'neutral' nations supervise the elections, which the North accepted. The U.S. supported the South Korean position, saying that the USSR wanted to turn North Korea into a puppet state. Most allies remained silent and at least one, Britain, thought that the South Korean–U.S. proposal would be deemed unreasonable.[7]

The South Korean representative proposed that all-Korea elections, be held according to South Korean constitutional procedures and still under UN supervision. On June 15, the last day of the conference on the Korean question, the USSR and China both submitted declarations in support of a unified, democratic, independent Korea, saying that negotiations to that end should resume at an appropriate time. The Belgian and British delegations said that while they were not going to accept "the Soviet and Chinese proposals, that did not mean a rejection of the ideas they contained".[8] In the end, however, the conference participants did not agree on any declaration.[citation needed]

Indochina

[edit]While the delegates began to assemble in Geneva in late April, the discussions on Indochina did not begin until 8 May 1954. The Viet Minh had achieved their decisive victory over the French Union forces at Dien Bien Phu the previous day.[3]: 549

The Western allies did not have a unified position on what the Conference was to achieve in relation to Indochina. Anthony Eden, leading the British delegation, favored a negotiated settlement to the conflict. Georges Bidault, leading the French delegation, vacillated and was keen to preserve something of France's position in Indochina to justify past sacrifices, even as the nation's military situation deteriorated.[3]: 559 The U.S. had been supporting the French in Indochina for many years and the Republican Eisenhower administration wanted to ensure that it could not be accused of another "Yalta" or of having "lost" Indochina to the Communists. Its leaders had previously accused the Democratic Truman administration of having "lost China" when the Communists were successful in securing control of virtually all of the country.

The Eisenhower administration had considered air strikes in support of the French at Dien Bien Phu but was unable to obtain a commitment to united action from key allies such as the United Kingdom. Eisenhower was wary of becoming drawn into "another Korea" that would be deeply unpopular with the American public. U.S. domestic policy considerations strongly influenced the country's position at Geneva.[3]: 551–53 Columnist Walter Lippmann wrote on 29 April that "the American position at Geneva is an impossible one, so long as leading Republican senators have no terms for peace except unconditional surrender of the enemy and no terms for entering the war except as a collective action in which nobody is now willing to engage."[3]: 554 At the time of the conference, the U.S. did not recognize the People's Republic of China. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, an anticommunist, forbade any contact with the Chinese delegation, refusing to shake hands with Zhou Enlai, the lead Chinese negotiator.[3]: 555

Dulles fell out with the UK delegate Anthony Eden over the perceived failure of the UK to support united action and U.S. positions on Indochina; he left Geneva on 3 May and was replaced by his deputy Walter Bedell Smith.[3]: 555–58 The State of Vietnam refused to attend the negotiations until Bidault wrote to Bảo Đại, assuring him that any agreement would not partition Vietnam.[3]: 550–51

Bidault opened the conference on 8 May by proposing a cessation of hostilities, a ceasefire in place, a release of prisoners of war, and a disarming of irregulars, despite the French surrender at Dien Bien Phu the previous day in northwestern Vietnam.[3]: 559–60

On 10 May, Phạm Văn Đồng, the leader of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) delegation set out their position, proposing a ceasefire; separation of the opposing forces; a ban on the introduction of new forces into Indochina; the exchange of prisoners; independence and sovereignty for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos; elections for unified governments in each country, the withdrawal of all foreign forces; and the inclusion of the Pathet Lao and Khmer Issarak representatives at the Conference.[3]: 560 Pham Van Dong first proposed a temporary partition of Vietnam on 25 May.[9] Following their victory at Dien Bien Phu and given the worsening French security position around the Red River Delta, a ceasefire and partition would not appear to have been in the interests of the DRV. It appears that the DRV leadership thought the balance of forces was uncomfortably close and was worried about morale problems in the troops and supporters, after eight years of war.[3]: 561 Robert F. Turner has argued that the Viet Minh might have prolonged the negotiations and continued fighting to achieve a more favorable position militarily, if not for Chinese and Soviet pressure on them to end the fighting.[9] In addition, there was a widespread perception that the Diem government would collapse, leaving the Viet Minh free to take control of the area.[10]

On 12 May, the State of Vietnam rejected any partition of the country, and the U.S. expressed a similar position the next day. The French sought to implement a physical separation of the opposing forces into enclaves throughout the country, known as the "leopard-skin" approach. The DRV/Viet Minh would be given the Cà Mau Peninsula, three enclaves near Saigon, large areas of Annam and Tonkin; the French Union forces would retain most urban areas and the Red River Delta, including Hanoi and Haiphong, allowing it to resume combat operation in the north, if necessary.[3]: 562–63

Behind the scenes, the U.S. and the French governments continued to discuss the terms for possible U.S. military intervention in Indochina.[3]: 563–66 By 29 May, the U.S. and the French had reached an agreement that if the Conference failed to deliver an acceptable peace deal, Eisenhower would seek Congressional approval for military intervention in Indochina.[3]: 568–69 However, after discussions with the Australian and New Zealand governments in which it became evident that neither would support U.S. military intervention, reports of the plummeting morale among the French Union forces and opposition from U.S. Army Chief of Staff Matthew Ridgway, the U.S. began to shift away from intervention and continued to oppose a negotiated settlement.[3]: 569–73 By early to mid-June, the U.S. began to consider the possibility that rather than supporting the French in Indochina, it might be preferable for the French to leave and for the U.S. to support the new Indochinese states. That would remove the taint of French colonialism. Unwilling to support the proposed partition or intervention, by mid-June, the U.S. decided to withdraw from major participation in the Conference.[3]: 574–75

On 15 June, Vyacheslav Molotov proposed that the ceasefire should be monitored by a supervisory commission, chaired by non-aligned India. On 16 June, Zhou Enlai stated that the situations in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos were not the same and should be treated separately. He proposed that Laos and Cambodia could be treated as neutral nations if they had no foreign bases. On 18 June, Pham Van Dong said the Viet Minh would be prepared to withdraw their forces from Laos and Cambodia if no foreign bases were established in Indochina.[3]: 581 The apparent softening of the Communist position appeared to arise from a meeting among the DRV, Chinese and Soviet delegations on 15 June in which Zhou warned the Viet Minh that its military presence in Laos and Cambodia threatened to undermine negotiations in relation to Vietnam. That represented a major blow to the DRV, which had tried to ensure that the Pathet Lao and Khmer Issarak would join the governments in Laos and Cambodia, respectively, under the leadership of the DRV. The Chinese likely also sought to ensure that Laos and Cambodia were not under Vietnam's influence in the future but under China's.[3]: 581–53

On 18 June, following a vote of no-confidence, the French Laniel government fell and was replaced by a coalition with Radical Pierre Mendès France as Prime Minister, by a vote of 419 to 47, with 143 abstentions.[3]: 579 Prior to the collapse of the Laniel government, France recognized Vietnam as "a fully independent and sovereign state" on 4 June.[11] A long-time opponent of the war, Mendès France had pledged to the National Assembly that he would resign if he failed to achieve a ceasefire within 30 days.[3]: 575 Mendès France retained the Foreign Ministry for himself, and Bidault left the Conference.[3]: 579 The new French government abandoned earlier assurances to the State of Vietnam that France would not pursue or accept partition, and it engaged in secret negotiations with the Viet Minh delegation, bypassing the State of Vietnam to meet Mendès France's self-imposed deadline.[12] On 23 June, Mendès France secretly met with Zhou Enlai at the French embassy in Bern. Zhou outlined the Chinese position that an immediate ceasefire was required, the three nations should be treated separately, and the two governments that existed in Vietnam would be recognized.[3]: 584

Mendès France returned to Paris. The following day he met with his main advisers on Indochina. General Paul Ély outlined the deteriorating military position in Vietnam, and Jean Chauvel suggested that the situation on the ground called for partition at the 16th or 17th parallel. The three agreed that the Bao Dai government would need time to consolidate its position and that U.S. assistance would be vital. The possibility of retaining Hanoi and Haiphong or just Haiphong was dismissed, as the French believed it was preferable to seek partition with no Viet Minh enclaves in the south.[3]: 585–87

On 16 June, twelve days after France granted full independence to the State of Vietnam,[13] Bao Dai appointed Ngo Dinh Diem as Prime Minister to replace Bửu Lộc. Diem was a staunch nationalist, both anti-French and anticommunist, with strong political connections in the U.S.[3]: 576 Diem agreed to take the position if he received all civilian and military powers.[13] Diem and his foreign minister, Tran Van Do, were strongly opposed to partition.

At Geneva, the State of Vietnam's proposal included "a ceasefire without a demarcation line" and "control by the United Nations... of the administration of the entire country [and] of the general elections, when the United Nations believes that order and security will have been everywhere truly restored."[14]

On 28 June following an Anglo-US summit in Washington, the UK and the U.S. issued a joint communique, which included a statement that if the Conference failed, "the international situation will be seriously aggravated." The parties also agreed to a secret list of seven minimum outcomes that both parties would "respect": the preservation of a noncommunist South Vietnam (plus an enclave in the Red River Delta if possible), future reunification of divided Vietnam, and the integrity of Cambodia and Laos, including the removal of all Viet Minh forces.[3]: 593–94

Also on 28 June, Tạ Quang Bửu, a senior DRV negotiator, called for the line of partition to be at the 13th parallel, the withdrawal of all French Union forces from the north within three months of the ceasefire, and the Pathet Lao to have virtual sovereignty over eastern Laos.[3]: 595–96

From 3 to 5 July, Zhou Enlai met with Ho Chi Minh and other senior DRV leaders in Liuzhou, Guangxi. Most of the first day was spent discussing the military situation and balance of forces in Vietnam, Giáp explained that while

Dien Bien Phu had represented a colossal defeat for France ... she was far from defeated. She retained a superiority in numbers—some 470,000 troops, roughly half of them Vietnamese, versus 310,000 on the Viet Minh side as well as control of Vietnam's major cities (Hanoi, Saigon, Huế, Tourane (Da Nang)). A fundamental alteration of the balance of forces had thus yet to occur, Giap continued, despite Dien Bien Phu.

Wei Guoqing, the chief Chinese military adviser to the Viet Minh, said he agreed. "If the U.S. does not interfere,' Zhou asked, "and assuming France will dispatch more troops, how long will it take for us to seize the whole of Indochina?" In the best scenario, Giap replied, "full victory could be achieved in two to three years. Worst case? Three to five years."[3]: 596

That afternoon Zhou "offered a lengthy exposition on the massive international reach of the Indochina conflict ... and on the imperative of preventing an American intervention in the war. Given Washington's intense hostility to the Chinese Revolution ... one must assume that the current administration would not stand idly by if the Viet Minh sought to win complete victory." Consequently, "if we ask too much at Geneva and peace is not achieved, it is certain that the U.S. will intervene, providing Cambodia, Laos, and Bao Dai with weapons and ammunition, helping them train military personnel, and establishing military bases there ... The central issue", Zhou told Ho, is "to prevent America's intervention" and "to achieve a peaceful settlement." Laos and Cambodia would have to be treated differently and be allowed to pursue their own paths if they did not join a military alliance or permit foreign bases on their territory. The Mendes France government, having vowed to achieve a negotiated solution, must be supported, for fear that it would fall and be replaced by one committed to continuing the war."[3]: 597 Ho pressed hard for the partition line to be at the 16th parallel while Zhou noted that Route 9, the only land route from Laos to the South China Sea ran closer to the 17th parallel.[3]: 597

Several days later the Communist Party of Vietnam's Sixth Central Committee plenum took place. Ho Chi Minh and General Secretary Trường Chinh took turns emphasizing the need for an early political settlement to prevent military intervention by the United States, now the "main and direct enemy" of Vietnam. "In the new situation we cannot follow the old program," Ho declared. "[B]efore, our motto was, 'war of resistance until victory.' Now, in view of the new situation, we should uphold a new motto: peace, unification, independence, and democracy." A spirit of compromise would be required by both sides to make the negotiations succeed, and there could be no more talk of wiping out and annihilating all the French troops. A demarcation line allowing the temporary regrouping of both sides would be necessary ..." The plenum endorsed Ho's analysis, passing a resolution supporting a compromise settlement to end the fighting. However, Ho and Truong Chinh plainly worried that following such an agreement in Geneva, there would be internal discontent and "leftist deviation", and in particular, analysts would fail to see the complexity of the situation and underestimate the power of the American and French adversaries. They accordingly reminded their colleagues that France would retain control of a large part of the country and that people living in the area might be confused, alienated, and vulnerable to enemy manipulations.

"We have to make it clear to our people," Ho said that "in the interest of the whole country, for the sake of long-term interest, they must accept this, because it is a glorious thing and the whole country is grateful for that. We must not let people have pessimistic and negative thinking; instead, we must encourage the people to continue the struggle for the withdrawal of French troops and ensure our independence."[3]: 597–98

The Conference reconvened on 10 July, and Mendès France arrived to lead the French delegation.[3]: 599 The State of Vietnam continued to protest against partition which had become inevitable, with the only issue being where the line should be drawn.[3]: 602 Walter Bedell Smith from the U.S. arrived in Geneva on 16 July, but the U.S. delegation was under instructions to avoid direct association with the negotiations.[3]: 602

All parties at the Conference called for reunification elections but could not agree on the details. Pham Van Dong proposed elections under the supervision of "local commissions." The U.S., with the support of Britain and the Associated States of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, suggested UN supervision. That was rejected by Molotov, who argued for a commission with an equal number of communist and noncommunist members, which could determine "important" issues only by unanimous agreement.[15] The negotiators were unable to agree on a date for the elections for reunification. The DRV argued that the elections should be held within six months of the ceasefire, and the Western allies sought to have no deadline. Molotov proposed June 1955 then softened to later in 1955 and finally July 1956.[3]: 610 The Diem government supported reunification elections but only with effective international supervision; it argued that genuinely free elections were impossible in the totalitarian North.[16]

By the afternoon of 20 July, the remaining outstanding issues were resolved as the parties agreed that the partition line should be at the 17th parallel and that the elections for reunification should be in July 1956, two years after the ceasefire.[3]: 604 The "Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities in Vietnam" was signed only by French and Viet Minh military commands.[15] Based on a proposal by Zhou Enlai, an International Control Commission (ICC) chaired by India, with Canada and Poland as members, was placed in charge of supervising the ceasefire.[3]: 603 [15] Because issues were to be decided unanimously, Poland's presence in the ICC provided the communists' effective veto power over supervision of the treaty.[15] The unsigned "Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference" called for reunification elections, which the majority of delegates expected to be supervised by the ICC. The Viet Minh never accepted ICC authority over such elections, stating that the ICC's "competence was to be limited to the supervision and control of the implementation of the Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities by both parties."[17] Of the nine delegates present, only the United States and the State of Vietnam refused to accept the declaration. Bedell Smith delivered a "unilateral declaration" of the U.S. position, reiterating: "We shall seek to achieve unity through free elections supervised by the United Nations to insure that they are conducted fairly."[18]

While the three agreements (later known as the Geneva Accords) were dated 20 July (to meet Mendès France's 30-day deadline) they were in fact signed on the morning of 21 July.[3]: 605 [19]

Provisions

[edit]The accords, which were issued on 21 July 1954 (taking effect two days later),[20] set out the following terms in relation to Vietnam:

- a "provisional military demarcation line" running approximately along the 17th Parallel "on either side of which the forces of the two parties shall be regrouped after their withdrawal".: 49

- a 3-mile-wide (4.8 km) demilitarized zone on each side of the demarcation line

- French Union forces regroup to the south of the line and Viet Minh to the north

- free movement of the population between the zone for three hundred days

- neither zone to join any military alliance or seek military reinforcement

- establishment of the International Control Commission, comprising Canada, Poland and India as chair, to monitor the ceasefire[3]: 605 [21]

- free general elections by secret ballot shall be held in July 1956, under the supervision of the International Supervisory Commission (it was recorded only in the unsigned Final Declaration of the Conference).

The Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference also stated that "The Conference recognizes that the essential purpose of the agreement relating to Viet-Nam is to settle military questions with a view to ending hostilities and that the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary" (Article 6).[22]

The agreement was signed by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, France, the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom. The State of Vietnam rejected the agreement,[23] while the United States stated that it "took note" of the ceasefire agreements and declared that it would "refrain from the threat or use of force to disturb them.[3]: 606

To put aside any notion specifically that the partition was permanent, an unsigned Final Declaration, stated in Article 6: "The Conference recognizes that the essential purpose of the agreement relating to Vietnam is to settle military questions with a view to ending hostilities and that the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary."[22]: 442

Division at the 17th Parallel meant that the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was giving up a large area currently under its control south of that line while gaining only a very small area, not already under its control, north of the line.[24]

Separate accords were signed by the signatories with the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Kingdom of Laos in relation to Cambodia and Laos respectively. Following the terms of the agreement, Laos would be governed by the Laotian royal court while Cambodia would be ruled by the royal court of Norodom Sihanouk. Despite retaining its monarchy, the agreement also allowed for "VWP-affiliated Laotian forces" to run the provinces of Sam Neua and Phongsal, further expanding North Vietnamese influence within Indochina. Communist forces in Cambodia, however, would remain out of power.[4]: 99

The British and Communist Chinese delegations reached an agreement on the sidelines of the Conference to upgrade their diplomatic relations.[25]

Reactions

[edit]

The DRV at Geneva accepted a much worse settlement than the military situation on the ground indicated. "For Ho Chi Minh, there was no getting around the fact that his victory, however unprecedented and stunning was incomplete and perhaps temporary. The vision that had always driven him on, that of a 'great union' of all Vietnamese, had flickered into view for a fleeting moment in 1945–46, then had been lost in the subsequent war. Now, despite vanquishing the French military, the dream remained unrealized ..."[3]: 620 That was partly as a result of the great pressure exerted by China (Pham Van Dong is alleged to have said in one of the final negotiating sessions that Zhou Enlai double-crossed the DRV) and the Soviet Union for their own purposes, but the Viet Minh had their own reasons for agreeing to a negotiated settlement, principally their own concerns regarding the balance of forces and fear of U.S. intervention.[3]: 607–09

France had achieved a much better outcome than could have been expected. Bidault had stated at the beginning of the Conference that he was playing with "a two of clubs and a three of diamonds" whereas the DRV had several aces, kings, and queens,[3]: 607 but Jean Chauvel was more circumspect: "There is no good end to a bad business."[3]: 613

In a press conference on 21 July, US President Eisenhower expressed satisfaction that a ceasefire had been concluded but stated that the U.S. was not a party to the Accords or bound by them, as they contained provisions that his administration could not support.[3]: 612 The State of Vietnam opposed the partition of Vietnam and the Geneva agreement.[26]

Aftermath

[edit]On 9 October 1954, the tricolore was lowered for the last time at the Hanoi Citadel and the last French Union forces left the city, crossing the Paul Doumer Bridge on their way to Haiphong for embarkation.[3]: 617–18

The Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference also stated that "The Conference recognizes that the essential purpose of the agreement relating to Viet-Nam is to settle military questions with a view to ending hostilities and that the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary" (Article 6).[22]

After the cessation of hostilities, a large migration took place. North Vietnamese, especially Catholics, intellectuals, business people, land owners, anti-communist democrats, and members of the middle class moved south of the Accords-mandated ceasefire line during Operation Passage to Freedom. The ICC reported that at least 892,876 North Vietnamese were processed through official refugee stations. The CIA attempted to further influence Catholic Vietnamese with slogans such as "the Virgin Mary is moving South".[27] The CIA's role in influencing the immigrants' decisions was minimal, since Catholic migrants were motivated mainly by their own convictions and circumstances rather than by external propaganda.[28] At least 500,000 Catholics, approximately 200,000 Buddhists, and tens of thousands from ethnic minority groups migrated to the South.[29]: 280 More might have left, but according to the Canadian members of the international peacekeeping mission, many North Vietnamese were prevented from leaving by "soldiers, political cadres, and local militias".[30] Around the same time, between 14,000 – 45,000 civilians and approximately 100,000 Viet Minh fighters moved in the opposite direction.[31][32][33]

The U.S. replaced the French as a political backup for Ngo Dinh Diem, the Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam, who asserted his power in the South. The Geneva conference had not provided any specific mechanisms for the national elections planned for 1956, and Diem refused to hold them by citing that the South had not signed and was not bound to the Geneva Accords and that it was impossible to hold free elections in the communist North. Instead, he went about attempting to crush communist opposition.[34][35] Robert F. Turner has argued that North Vietnam violated the Geneva Accords by failing to withdraw all Viet Minh troops from South Vietnam, stifling the movement of North Vietnamese refugees, and conducting a military buildup that more than doubled the number of armed divisions in the North Vietnamese army while the South Vietnamese army was reduced by 20,000 men.[36]

On 20 May 1955, French Union forces withdrew from Saigon to a coastal base and on 28 April 1956, the last French forces left Vietnam.[3]: 650

In July 1955, the prime minister of the State of Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, announced that South Vietnam would not participate in elections to unify the country. He said that the State of Vietnam had not signed the Geneva Accords and was therefore not bound by it.[37][38] The failure of reunification led to the creation of the National Liberation Front (better known as the Viet Cong) by Ho Chi Minh's government. They were closely aided by the Vietnam People's Army (VPA) of the North, also known as the North Vietnamese Army. The result was the Vietnam War. The Vietnamese communist leadership never expected the 1956 election to take place, nor did they believe peaceful reunification was possible. They saw military force as the only way to reunite the country but continued to raise the election issue for its propaganda value.[39]

Despite glaring errors with the partition, the Chinese would still manage to largely benefit from the conference's results. In addition to gaining an independent North Vietnam, China would also open up "dialogues with France, Britain, and the United States". Furthermore, China, as a result of this expanded and moderate international approach, also helped to weaken America's attempt to label China as a "Red" radical within the region.[4]: 99

Historian John Lewis Gaddis said that the 1954 accords "were so hastily drafted and ambiguously worded that, from the standpoint of international law, it makes little sense to speak of violations from either side".[40] Historian Christopher Goscha pointed out that while the Geneva Conference brought an end to French fighting, it failed to prevent the resurgence of a Vietnamese civil war or more direct American military involvement in Indochina.[29]: 272, 284

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Goscha 2011.

- ^ Archive, Wilson Center Digital. "Wilson Center Digital Archive". digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au Logevall, Fredrik (2012). Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-64519-1.

- ^ a b c d Garver, John (2016). China's Quest: The History Of The Foreign Relations of The People's Republic of China. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-026105-4.

- ^ "Text of the Korean War Armistice Agreement". Findlaw. Columbia University. July 27, 1953. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "National Intelligence Estimate NIE 63-5-54" (PDF). CIA Reading Room. 3 August 1954.

- ^ a b Bailey, Sydney D. (1992). The Korean Armistice. St. Martin's Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-349-22104-2.

- ^ Bailey, Sydney D. (1992). The Korean Armistice. St. Martin's Press. pp. 167–68. ISBN 978-1-349-22104-2.

- ^ a b Turner 1975, p. 92.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 108.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 93.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 88.

- ^ a b Turner 1975, p. 94.

- ^ Turner 1975, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c d Turner 1975, p. 97.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 107.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 99.

- ^ Turner 1975, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 96.

- ^ "The Final Declarations of the Geneva Conference July 21, 1954". The Wars for Viet Nam. Vassar College. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ (Article 3) (N. Tarling, The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume Two Part Two: From World War II to the present, Cambridge University Press, p. 45)

- ^ a b c McTurnan Kahin, George; Lewis, John W. (1967). The United States in Vietnam. Dial Press.

- ^ Ang Cheng Guan (1997). Vietnamese Communists' Relations with China and the Second Indochina War (1956–62). Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 11. ISBN 0-7864-0404-3.

- ^ Fall, Bernard B. (December 1956). "Indochina: The Last Year of the War: The Navarre Plan". Military Review. 36 (9). US Army Command and General Staff College: 56.

- ^ Lowe, Peter (1997). Containing the Cold War in East Asia: British Policies Towards Japan, China, and Korea, 1948–53. Manchester University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-7190-2508-2. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Cable, James (1986). The Geneva Conference of 1954 on Indochina. Macmillan Press. pp. 120, 123. ISBN 9781349182909.

- ^ Patrick J. Hearden (2017). The Tragedy of Vietnam. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-351-67400-3. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Hansen, Peter (2009). "Bắc Di Cư: Catholic Refugees from the North of Vietnam, and Their Role in the Southern Republic, 1954–1959". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 4 (3). University of California Press: 173–211. doi:10.1525/vs.2009.4.3.173.

- ^ a b Goscha, Christopher (2016). Vietnam: A New History. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465094370.

- ^ Lind, Michael (1999). Vietnam, The Necessary War: A Reinterpretation of America's Most Disastrous Military Conflict. Free Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-684-84254-8.

- ^ Trân, Thi Liên (2005). "The Catholic Question in North Vietnam: From Polish Sources, 1954–56". Cold War History. London: Routledge. 5 (4): 427–49. doi:10.1080/14682740500284747.

- ^ Frankum, Ronald (2007). Operation Passage to Freedom: The United States Navy in Vietnam, 1954–55. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-608-6.

- ^ Ruane, Kevin (1998). War and Revolution in Vietnam. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85728-323-5.

- ^ Keylor, William. "The 20th Century World and Beyond: An International History Since 1900," p. 371, Oxford University Press: 2011.

- ^ David L. Anderson (2010). The Columbia History of the Vietnam War. Columbia University Press. p. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-231-13480-4.

- ^ Turner 1975, p. 100–04.

- ^ "Lời tuyên bố truyền thanh của Thủ tướng Chánh phủ ngày 16-7-1955 về hiệp định Genève và vấn đề thống nhất đất nước"; "Tuyên ngôn của Chánh phủ Quốc gia Việt Nam ngày 9-8-1955 về vấn đề thống nhất lãnh thổ"". Con đường Chính nghĩa: Độc lập, Dân chủ (in Vietnamese). Vol. II. Saigon: Sở Báo chí Thông tin, Phủ Tổng thống. 1956. pp. 11–13.

- ^ Ang Cheng Guan (1997). Vietnamese Communists' Relations with China and the Second Indochina War (1956–62). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7864-0404-9. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ Ang Cheng Guan (1997). Vietnamese Communists' Relations with China and the Second Indochina War (1956–62). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7864-0404-9.

- ^ Fadiman, Anne. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1997. p. 126.

Sources

[edit]- Asselin, Pierre (May 2011). "The Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the 1954 Geneva Conference: A revisionist critique". Cold War History. 11 (2): 155–195. doi:10.1080/14682740903244934. ISSN 1468-2745.

- Hannon, John S. Jr (1967–1968). "A Political Settlement for Vietnam: The 1954 Geneva Conference and Its Current Implications". Virginia Journal of International Law. 8: 4.

- Turner, Robert F. (1975). Vietnamese Communism: Its Origins and Development. Stanford: Hoover Institution Publications. ISBN 978-0-8179-1431-8.

- Waite, James (2012). The End of the First Indochina War: A Global History. Routledge studies on history and globalization. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-27335-3.

- The 1954 Geneva Conference; Indo-China and Korea. New York: Greenwood Press. 1968.

- Goscha, Christopher E. (2011). "Geneva Accords". Historical Dictionary of the Indochina War (1945–1954): An International and Interdisciplinary Approach. NIAS Press. ISBN 9788776940638.

External links

[edit]- The 1954 Geneva Conference, Wilson Center – Cold War International History Project.

- "The Geneva Conference of 1954 – New Evidence from the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China" (PDF). Cold War International History Project Bulletin (16). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 2008-04-22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- Bibliography: Dien Bien Phu and the Geneva Conference

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, Vol.XVI, The Geneva Conference. Available through the Foreign Relations of the United States online collection at the University of Wisconsin.