Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Drunk driving.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Drunk driving

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. The specific issue is: Specific details are given for laws in the U.S. and prevalence in Europe, but these details are missing for other parts of the world (December 2023) |

Drunk driving (or drink-driving in British English[1]) is the act of driving under the influence of alcohol. A small increase in the blood alcohol content increases the relative risk of a motor vehicle crash.[2]

In the United States, alcohol is involved in 32% of all traffic fatalities.[3][4]

Terminology

[edit]United States

[edit]In the United States, most states have generalized their criminal offense statutes to driving under the influence (DUI). These DUI statutes generally cover intoxication by any drug, including alcohol. Such laws may also apply to operating boats, aircraft, farm machinery, horse-drawn carriages, and bicycles. Specific terms used to describe alcohol-related driving offenses include "drinking and driving", "drunk driving", and "drunken driving". Most DUI offenses are alcohol-related so the terms are used interchangeably in common language, and "drug-related DUI" is used to distinguish.

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, there are two separate offences to do with alcohol and driving. The first is "Driving or attempting to drive with excess alcohol" (legal code DR10), the other is known as "In charge of a vehicle with excess alcohol" (legal code DR40) or "drunk in charge" due to the wording of the Licensing Act 1872.[5][6] In relation to motor vehicles, the Road Safety Act 1967 created a narrower offense of driving (or being in charge of) a vehicle while having breath, blood, or urine alcohol levels above the prescribed limits (colloquially called "being over the limit").[7] These provisions were re-enacted in the Road Traffic Act 1988. A separate offense in the 1988 Act applies to bicycles. While the 1872 Act is mostly superseded, the offense of being "drunk while in charge ... of any carriage, horse, cattle, or steam engine" is still in force; "carriage" has sometimes been interpreted as including mobility scooters.[6] )

European Union

[edit]In the European Union, the term "drink-driving" is used in the Directive (EU) 2015/413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2015 facilitating cross-border exchange of information on road-safety-related traffic offences. In this directive drink-driving means driving while impaired by alcohol, as defined in the law of the Member State of the offence.[8]

Measurement of intoxication

[edit]

Depending on the jurisdiction, a drunk driver's level of intoxication may be measured by police using three methods: blood, breath, or urine, resulting in a blood alcohol concentration, breath alcohol concentration (BrAC), or urine result. For law enforcement purposes, breath analysis using a breathalyzer is the preferred method, since results are available almost instantaneously. A measurement in excess of the specific threshold level, such as a BAC of 0.08% (8 basis points), defines the criminal offense with no need to prove impairment.[9]

In some jurisdictions, there is an aggravated category of the offense at a higher BAC level, such as 0.12%, 0.15%, or 0.25%. In many jurisdictions, police officers can conduct field tests of suspects to look for signs of intoxication.[10] There have been cases in Canada where officers have come upon a suspect who is unconscious after a crash and officers have taken a blood sample.[citation needed]

With the advent of a scientific test for BAC, law enforcement regimes moved from field sobriety testing (e.g., asking the suspect to stand on one leg) to having more than a prescribed amount of blood alcohol content while driving. However, this does not preclude the simultaneous existence and use of the older subjective tests in which police officers measure the intoxication of the suspect by asking them to do certain activities or by examining their eyes and responses.[11] The validity of the testing equipment/methods for determining breath and blood alcohol and mathematical relationships between breath/blood alcohol and intoxication levels have been criticized.[12] Improper testing and equipment calibration is often used in defense of a DUI or DWI.[13]

Effects of alcohol

[edit]Effects on cognitive processes

[edit]

Alcohol is a depressant, which mainly affects the function of the brain. Alcohol first affects the most vital components of the brain and "when the brain cortex is released from its functions of integrating and control, processes related to judgment and behavior occur in a disorganized fashion and the proper operation of behavioral tasks becomes disrupted."[14] Alcohol weakens a variety of skills that are necessary to perform everyday tasks. Drinking enough alcohol to cause a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.03–0.12% typically causes a flushed, red appearance in the face and impaired judgment and fine muscle coordination. A BAC of 0.09% to 0.25% causes lethargy, sedation, balance problems, and blurred vision. A BAC from 0.18% to 0.30% causes profound confusion, impaired speech (e.g., slurred speech), staggering, dizziness, and vomiting. A BAC from 0.25% to 0.40% causes stupor, unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, vomiting, and respiratory depression (potentially life-threatening). A BAC from 0.35% to 0.80% causes a coma (unconsciousness), life-threatening respiratory depression, and possibly fatal alcohol poisoning. There are a number of factors that affect the time in which BAC will reach or exceed 0.08, including weight, the time since one's recent drinking, and whether and what one ate within the time of drinking. A 170lb male can drink more than a 135lb female, before being over the BAC level.[15]

One of the main effects of alcohol is severely impairing a person's ability to shift attention from one thing to another, "without significantly impairing sensory motor functions."[14] This indicates that people who are intoxicated are not able to properly shift their attention without affecting the senses. People that are intoxicated also have a much more narrow area of usable vision than people who are sober. The information the brain receives from the eyes "becomes disrupted if eyes must be turned to the side to detect stimuli, or if eyes must be moved quickly from one point to another."[14]

Effects on driving

[edit]

Research shows an exponential increase of the relative risk for a crash with a linear increase of BAC.[17] NHTSA reports that the following blood alcohol levels (BAC) in a driver will have the following predictable effects on his or her ability to drive safely: (1) A BAC of .02 will result in a "[d]ecline in visual functions (rapid tracking of a moving target), a decline in the ability to perform two tasks at the same time (divided attention)"; (2) A BAC of .05 will result in "[r]educed coordination, reduced ability to track moving objects, difficulty steering, reduced response to emergency driving situations"; (3) A BAC of .08 will result in "[c]oncentration, short-term memory loss, speed control, reduced information processing capability (e.g., signal detection, visual search), impaired perception"; (4) A BAC of .10 will result in "[r]educed ability to maintain lane position and brake appropriately"; and (5) A BAC of .15 will result in "[s]ubstantial impairment in vehicle control, attention to driving task, and in necessary visual and auditory information processing."[18]

Several testing mechanisms are used to gauge a person's ability to drive, which indicate levels of intoxication. One of these is referred to as a tracking task, testing hand–eye coordination, in which "the task is to keep an object on a prescribed path by controlling its position through turning a steering wheel. Impairment of performance is seen at BACs of as little as 0.7 mg/mL (0.066%)."[14] Another form of tests is a choice reaction task, which deals more primarily with cognitive function. In this form of testing both hearing and vision are tested and drivers must give a "response according to rules that necessitate mental processing before giving the answer."[14] This is a useful gauge because in an actual driving situation drivers must divide their attention "between a tracking task and surveillance of the environment."[14] It has been found that even "very low BACs are sufficient to produce significant impairment of performance" in this area of thought process.[14]

Grand Rapids Dip

[edit]

A 1964 paper by Robert Frank Borkenstein studied data from Grand Rapids, Michigan.[19] The main finding of the Grand Rapids study was that for higher values of BAC, the collision risk increases steeply; for a BAC of 0.15%, the risk is 25 times higher than for zero blood alcohol. The BAC limits in Germany and many other countries were set based on this Grand Rapids study. Subsequent research showed that all extra collisions caused by alcohol were due to at least 0.06% BAC, 96% of them due to BAC above 0.08%, and 79% due to BAC above 0.12%.[20] One surprising aspect of the study was that, in the main analysis, a BAC of 0.01–0.04% was associated with a lower risk of collisions than a BAC of 0%, a feature referred to as the Grand Rapids Effect or Grand Rapids Dip.[20][21] A 1995 Würzburg University study of German data similarly found that the risk of collisions appeared to be lower for drivers with a BAC of 0.04% or less than for drivers with a BAC of 0%.[20]

Studies of alcohol impairment on tests of driving ability have found that impairment starts as soon as alcohol is detectable. Thus, the literature has for the most part treated the Grand Rapids Dip as a statistical effect, similar to Simpson's paradox.[22] The analysis in the Grand Rapids paper relied primarily on univariate statistics, which could not isolate the effects of age, gender, and drinking practices from the effects of other variables.[23] In particular, when the data is re-analyzed by constructing separate BAC-crash rate graphs for each drinking frequency, there are no J-shapes in any of the graphs and collision rates increase starting from 0% BAC. The analysis of the Grand Rapids study was biased by including drivers younger than 25 and older than 55 that did not drink often but had significantly higher crash rates even when not drinking alcohol.[22] A newer study using data from 1997-1999 replicated the Grand Rapids dip but found that adjusting for covariates using logistic regression made the dip disappear.[16]

Perceived recovery rate

[edit]A direct effect of alcohol on a person's brain is an overestimation of how quickly their body is recovering from the effects of alcohol. A study, discussed in the article "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel", was done with college students in which the students were tested with "a hidden maze learning task as their BAC [Blood Alcohol Content] both rose and fell over an 8-hour period."[2] The researchers found through the study that as the students became more drunk there was an increase in their mistakes "and the recovery of the underlying cognitive impairments that lead to these errors is slower, and more closely tied to the actual blood alcohol concentration, than the more rapid reduction in participants' subjective feeling of drunkenness."[2]

The participants believed that they were recovering from the adverse effects of alcohol much more quickly than they actually were. This feeling of perceived recovery is a plausible explanation of why so many people feel that they are able to safely operate a motor vehicle when they are not yet fully recovered from the alcohol they have consumed, indicating that the recovery rates do not coincide.

This thought process and brain function that is lost under the influence of alcohol is a very key element in regards to being able to drive safely, including "making judgments in terms of traveling through intersections or changing lanes when driving."[2] These essential driving skills are lost while a person is under the influence of alcohol.

Risks

[edit]

Drunk driving is one of the largest risk factors that contribute to traffic collisions. As of 2015, for people in Europe between the age of 15 and 29, driving under the influence of alcohol has been one of the main causes of mortality.[24] According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, alcohol-related crashes cause approximately $37 billion in damages annually.[25] DUI and alcohol-related crashes have produced an estimated $45 billion in damages every year. The combined costs of towing and storage fees, attorney fees, bail fees, fines, court fees, ignition interlock devices, traffic school fees and DMV fees mean that a first-time DUI charge could cost thousands to tens of thousands of dollars.[26]

Traffic collisions are predominantly caused by driving under the influence for people in Europe between the age of 15 and 29, it is one of the main causes of mortality.[24] According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, alcohol-related collisions cause approximately $37 billion in damages annually.[25] Every 51 minutes someone dies from an alcohol-related collision. When it comes to risk-taking there is a large male predominance, as personality traits, anti-social behaviour, and risk-taking are taken into consideration as they all are involved in DUI's.[27] Over 7.7 million underage people ages 12–20 claim to drink alcohol, and on average, for every 100,000 underage Americans, 1.2 died in drunk-driving traffic crashes.[28]

Characteristics of drunk drivers

[edit]Personality traits

[edit]Although situations differ and each person is unique, some common traits have been identified among drunk drivers. In the study "personality traits and mental health of severe drunk drivers in Sweden", 162 Swedish DUI offenders of all ages were studied to find links in psychological factors and characteristics. There are a wide variety of characteristics common among DUI offenders which are discussed, including: "anxiety, depression, inhibition, low assertiveness, neuroticism and introversion".[29] There is also a more specific personality type found, typically more antisocial, among repeat DUI offenders. It is not uncommon for them to actually be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and exhibit some of the following personality traits: "low social responsiveness, lack of self-control, hostility, poor decision-making lifestyle, low emotional adjustment, aggression, sensation seeking and impulsivity".[29]

It is also common for offenders to use drinking as a coping mechanism, not necessarily for social or enjoyment reasons, when they are antisocial in nature and have a father with a history of alcoholism. Offenders who begin drinking at an earlier age for thrills and "fun" are more likely to be antisocial later in their lives. The majority of the sample, 72%, came from what is considered more "normal" circumstances. This group was older when they began drinking, came from families without a history of alcoholism, were relatively well-behaved as children, were not as physically and emotionally affected by alcohol when compared with the rest of the study, and had the less emotional complications, such as anxiety and depression. The smaller portion of the sample, 28%, comes from what is generally considered less than desirable circumstances, or "not normal". They tended to start drinking heavily earlier in life and "exhibited more premorbid risk factors, had a more severe substance abuse and psychosocial impairment."[29]

Various characteristics associated with drunk drivers were found more often in one gender than another. Females were more likely to be affected by both mental and physical health problems, have family and social problems, have a greater drug use, and were frequently unemployed. However, the females tended to have less legal issues than the typical male offender. Some specific issues females dealt with were that "almost half of the female alcoholics had previously attempted to commit suicide, and almost one-third had suffered from anxiety disorder." In contrast with females, males were more likely to have in-depth problems and more involved complications, such as "a more complex problem profile, i.e. more legal, psychological, and work-related problems when compared with female alcoholics."[29] In general the sample, when paralleled with control groups, was tested to be much more impulsive in general.

Another commonality among the whole group was that the DUI offenders were more underprivileged when compared with the general population of drivers. A correlation has been found between lack of conscientiousness and accidents, meaning that "low conscientiousness drivers were more often involved in driving accidents than other drivers." When tested the drivers scored very high in the areas of "depression, vulnerability (to stress), gregariousness, modesty, tender mindedness", but significantly lower in the areas of "ideas (intellectual curiosity), competence, achievement striving and self-discipline."[29] The sample also tested considerably higher than the norm in "somatization, obsessions–compulsions, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoia, psychoticism", especially in the area of depression. Through this testing a previously overlooked character trait of DUI offenders was uncovered by the "low scores on the openness to experience domain."[29] This area "includes intellectual curiosity, receptivity to the inner world of fantasy and imagination, appreciation of art and beauty, openness to inner emotions, values, and active experiences." In all these various factors, there is only one which indicates relapses for driving under the influence: depression.[29]

Cognitive processes

[edit]Not only can personality traits of DUI offenders be dissimilar from the rest of the population, but so can their thought processes, or cognitive processes. They are unique in that "they often drink despite the severity of legal and financial sanctions imposed on them by society."[30]

In addition to these societal restraints, DUI offenders ignore their own personal experience, including both social and physical consequences. The study "Cognitive Predictors of Alcohol Involvement and Alcohol consumption-Related Consequences in a Sample of Drunk-Driving Offenders" was performed in Albuquerque, New Mexico on the cognitive, or mental, factors of DUI offenders. Characteristics such as gender, marital status, and age of these DWI offenders were similar to those in other populations. Approximately 25% of female and 21% of male offenders had received "a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse" and 62% of females and 70% of males "received a diagnosis of alcohol dependence."[30] All of the offenders had at least one DWI and males were more likely to have multiple citations. In terms of drinking patterns approximately 25% stated that "they had drunk alcohol with in the past day, while an additional 32% indicated they had drunk within the past week."[30] In regards to domestic drinking, "25% of the sample drank at least once per week in their own homes."[30] Different items were tested to see if they played a role in the decision to drink alcohol, which includes socializing, the expectation that drinking is enjoyable, financial resources to purchase alcohol, and liberation from stress at the work place. The study also focused on two main areas, "intrapersonal cues", or internal cues, that are reactions "to internal psychological or physical events" and "interpersonal cues" that result from "social influences in drinking situations."[30] The two largest factors between tested areas were damaging alcohol use and its correlation to "drinking urges/triggers."[30] Once again different behaviors are characteristic of male and female. Males are "more likely to abuse alcohol, be arrested for DWI offenses, and report more adverse alcohol-related consequences." However, effects of alcohol on females vary because the female metabolism processes alcohol significantly when compared to males, which increases their chances for intoxication.[30] The largest indicator for drinking was situational cues which comprised "indicators tapping psychological (e.g. letting oneself down, having an argument with a friend, and getting angry at something), social (e.g. relaxing and having a good time), and somatic cues (e.g. how good it tasted, passing by a liquor store, and heightened sexual enjoyment)."[30]

It may be that internal forces are more likely to drive DWI offenders to drink than external, which is indicated by the fact that the brain and body play a greater role than social influences. This possibility seems particularly likely in repeat DWI offenders, as repeat offences (unlike first-time offences) are not positively correlated with the availability of alcohol.[31] Another cognitive factor may be that of using alcohol to cope with problems. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the DWI offenders do not use proper coping mechanisms and thus turn to alcohol for the answer. Examples of such issues "include fights, arguments, and problems with people at work, all of which imply a need for adaptive coping strategies to help the high-risk drinker to offset pressures or demands."[30] DWI offenders would typically prefer to turn to alcohol than more healthy coping mechanisms and alcohol can cause more anger which can result in a vicious circle of drinking more alcohol to deal with alcohol-related issues. This is a not the way professionals tell people how to best deal with the struggles of everyday life and calls for "the need to develop internal control and self-regulatory mechanisms that attenuate stress, mollify the influence of relapse-based cues, and dampen urges to drink as part of therapeutic interventions."[30]

Field sobriety testing

[edit]To attempt to determine whether a suspect is impaired, police officers in the United States usually will administer field sobriety tests to determine whether the officer has probable cause to arrest an individual for suspicion of driving under the influence (DUI). The Preliminary Breath Test (PBT) or Preliminary Alcohol Screening test (PAS) is sometimes categorized as part of field sobriety testing, although it is not part of the series of performance tests. Commercial drivers are subject to PBT testing in some US states as a "drug screening" requirement.

Laws by country

[edit]

The laws relating to drunk driving vary significantly between countries, particularly the BAC limit before a person is charged with a crime. Thresholds range from the limit of detection (zero-tolerance) to 0.08%. Some countries have no limits or laws on blood alcohol content.[33] Some jurisdictions have multiple levels of BAC for different categories of drivers. In some jurisdictions, impaired drivers who injure or kill another person while driving may face heavier penalties. Some jurisdictions have judicial guidelines requiring a mandatory minimum sentence for certain situations. DUI convictions may result in multi-year jail terms and other penalties ranging from fines and other financial penalties to forfeiture of one's license plates and vehicle. In many jurisdictions, a judge may also order the installation of an ignition interlock device. Some jurisdictions require that drivers convicted of DUI offenses use special license plates that are easily distinguishable from regular plates, known in popular parlance as "party plates"[34] or "whiskey plates".

Implied consent laws

[edit]There are laws in place to protect citizens from drunk drivers, called implied consent laws. Drivers of any motor vehicle automatically consent to these laws, which include the associated testing, when they begin driving.

In most jurisdictions (with the notable exception of a few, such as Brazil), refusing consent is a different crime from drunk driving itself and has its own set of consequences. There have been cases where drivers were "acquitted of the DWI [driving while intoxicated] offense and convicted of the refusal (they are separate offenses), often with significant consequences (usually license suspension)".[35] A driver must give their full consent to comply with testing because "anything short of an unqualified, unequivocal assent to take the Breathalyzer test constitutes a refusal."[35] It has also been ruled that defendants are not allowed to request testing after they have already refused in order to aid officers' jobs "to remove intoxicated drivers from the roadways" and ensure that all results are accurate.[35]

United States

[edit]The United States has extensive case law and law enforcement programs related to drunk driving.

Solutions

[edit]Criminologist Hung-En Sung has concluded in 2016 that with regards to reducing drunk driving, law enforcement has not generally proven to be effective. Worldwide, the majority of those driving under the influence do not end up arrested. At least two-thirds of alcohol-involved fatalities involve repeat drinking drivers. Sung, commenting on measures for controlling drunk driving and alcohol-related accidents, noted that the ones that have proven effective include "lowering legal blood alcohol concentrations, controlling liquor outlets, nighttime driving curfews for minors, educational treatment programs combined with license suspension for offenders, and court monitoring of high-risk offenders."[36] In general, programs aimed at reducing society's consumption of alcohol, including education in schools, are seen as an effective long-term solution. Strategies aiming to reduce alcohol consumption among adult offenders have various estimates of effectiveness.[37]

Reducing alcohol consumption

[edit]Studies have shown that there are various methods to help reduce alcohol consumption:

- increasing the price of alcohol.[38]

- restricting opening hours of places where alcohol can be bought and consumed

- restricting places where alcohol can be bought and consumed, such as banning the sale of alcohol in petrol stations and transport cafes

- increasing the minimum drinking age.[38]

Separating drinking from driving

[edit]

One tool used to separate drinking from driving is an ignition interlock device which requires the driver to blow into a mouthpiece on the device before starting or continuing to operate the vehicle.[38] This tool is used in rehabilitation programmes and for school buses.[38] Studies have indicated that ignition interlock devices can reduce drunk driving offences by between 35% and 90%, including 60% for a Swedish study, 67% for the CDCP, and 64% for the mean of several studies.[38] The US may require monitoring systems to stop intoxicated drivers in new vehicles as early as 2026.[39]

Designated driver programmes

[edit]A designated driver programme helps to separate driving from drinking in social places such as restaurants, discos, pubs, bars. In such a programme, a group chooses who will be the drivers before going to a place where alcohol will be consumed; the drivers abstain from alcohol. Members of the group who do not drive would be expected to pay for a taxi when it is their turn.[38]

Reducing the legal blood alcohol concentration limit

[edit]Reduction of legal limit from 0.8 g/L to 0.5 g/L reduced fatal crashes by 2% in some European countries; while similar results were obtained in the United States[38] Lower legal limit (0.1 g/L in Austria and 0 g/L in Australia and the United States) have helped to reduce fatalities among young drivers. However, in Scotland, lowering the legal limit of blood alcohol content from 0.08% to 0.05% did not result in fewer road traffic collisions in two years after the introducing the new law. One possible explanation is that this might be due the poor publicity and enforcement of the new law and the lack of random breath testing.[40][41]

Police enforcement

[edit]Enforcing the legal limit for alcohol consumption is the usual method to reduce drunk driving.

Experience shows that:

- introduction of breath testing devices by the police in the 1970s had a significant effect, but alcohol remains a factor in 25% of all fatal crashes in Europe[38]

- fines appear to have little effect on reducing alcohol-impaired driving[38]

- driving licence measures with a duration of 3 to 12 months[clarification needed]

- imprisonment is the least effective remedy

Education

[edit]

Education programmes used to reduce drunk driving levels include:

- driver education in schools and in basic driver training

- driver improvement courses on alcohol (rehabilitation courses)

- public campaigns

- promotion of safety culture

Prevalence

[edit]In the United States, local law enforcement agencies made 1,467,300 arrests nationwide for driving under the influence of alcohol in 1996, compared to 1.9 million such arrests during the peak year in 1983.[42] In 1997 an estimated 513,200 DWI offenders were in prison or jail, down from 593,000 in 1990 and up from 270,100 in 1986.[43] In the United States, DUI and alcohol-related collisions produce an estimated $45 billion in damages every year.[44]

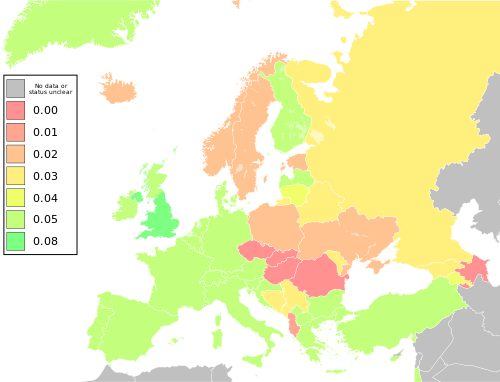

In Europe, about 25% of all road fatalities are alcohol-related, while very few Europeans drive under the influence of alcohol. According to estimates, 3.85% of drivers in European Union drive with a BAC of 0.2 g/L and 1.65% with a BAC of 0.5 g/L and higher. For alcohol in combination with drugs and medicines, the rates are respectively 0.35% and 0.16%.[38]

View source data.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "drink-driving". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel". Science Daily. 18 August 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Alcohol-Impaired Driving". NHTSA. 2018.

- ^ "Drunk Driving Fatality Statistics". Responsibility.org. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Magistrates' Court Sentencing Guidelines" (PDF). Sentencing Guidelines Council. May 2008. p. 188. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ a b Merritt, Jonathan (9 July 2009). Law for Student Police Officers. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-84445-563-8.

- ^ Hannibal, Martin; Hardy, Stephen (4 March 2013). Practice Notes on Road Traffic Law 2/e. Routledge. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-1-135-34638-6.

- ^ Directive (EU) 2015/413

- ^ Nelson, Bruce. "Nevada's Driving Under the Influence (DUI) laws". NVPAC. Advisory Council for Prosecuting Attorneys. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Florida DUI and Administrative Suspension Laws". FLHSMV. Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Ethanol Level". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Bates, Marsha E. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. "The Correspondence between Saliva and Breath Estimates of Blood Alcohol Concentration: Advantages and Limitations of the Saliva Method". Journal of Studies in Alcohol, 1 Jan. 1993. Web. 13 Mar. 2013.

- ^ Clark, Paula A (2013). "The Right to Challenge the Accuracy of Breath Test Results Under Alaska Law". Alaska Law Review. 30: 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mattila, Maurice J. (2001). Encyclopedia of drugs, alcohol and addictive behavior. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 0-02-865541-9.

- ^ National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). BAC Estimator [computer program]. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service, 1992.

- ^ a b Blomberg, Richard D.; Peck, Raymond C.; Moskowitz, Herbert; Burns, Marcelline; Fiorentino, Dary (August 2009). "The Long Beach/Fort Lauderdale relative risk study". Journal of Safety Research. 40 (4): 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2009.07.002. PMID 19778652.

- ^ a b "Preventing road traffic injury: A public health perspective for Europe" (PDF). Euro.who.int. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ NHTSA (4 October 2016). "Drunk Driving – How Alcohol Affects Driving Ability". NHTSA. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Robert F. Borkenstein papers, 1928–2002, Indiana U. The role of the drinking driver in traffic accidents (Researchgate link)

- ^ a b c Grand Rapids Effects Revisited: Accidents, Alcohol and Risk Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, H.-P. Krüger, J. Kazenwadel and M. Vollrath, Center for Traffic Sciences, University of Wuerzburg, Röntgenring 11, D-97070 Würzburg, Germany

- ^ Hurst, Paul M.; Harte, David; Frith, William J. (October 1994). "The Grand Rapids dip revisited". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 26 (5): 647–654. doi:10.1016/0001-4575(94)90026-4. PMID 7999209.

- ^ a b Ogden, E. J.D.; Moskowitz, H. (September 2004). "Effects of Alcohol and Other Drugs on Driver Performance". Traffic Injury Prevention. 5 (3): 185–198. doi:10.1080/15389580490465201. PMID 15276919. S2CID 2839336.

- ^ "Driver Characteristics and Impairment at Various BACs – Introduction". one.nhtsa.gov.

- ^ a b Alonso, Francisco; Pasteur, Juan C.; Montero, Luis; Esteban, Cristina (2015). "Driving under the influence of alcohol: frequency, reasons, perceived risk and punishment". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 10 (11): 11. doi:10.1186/s13011-015-0007-4. PMC 4359384. PMID 25880078.

- ^ a b "Impaired Driving - National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)". Nhtsa.gov. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "How Much Does a DUI Cost". Administrative Office of the Courts. State of California. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Anum, EA; Silberg, J; Retchin, SM (2014). "Heritability of DUI convictions: a twin study of driving under the influence of alcohol". Twin Res Hum Genet. 17 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1017/thg.2013.86. PMID 24384043. S2CID 206345742.

- ^ "Underage Drinking." National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/underagedrinking/underagefact.htm.

- ^ a b c d e f g Huckba, B. (July 2010). "Personality traits and mental health of severe drunk drivers in Sweden". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 45 (7): 723–31. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0111-8. PMID 19730762. S2CID 20165169.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Scheier, L. M.; Lapham, S. C.; C'de Baca, J. (2008). "Cognitive predictors of alcohol involvement and alcohol-related consequences in a sample of drunk-driving offenders". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (14): 2089–2115. doi:10.1080/10826080802345358. PMID 19085438. S2CID 25196512. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Schofield, Timothy B.; Denson, Thomas F. (7 August 2013). "Temporal Alcohol Availability Predicts First-Time Drunk Driving, but Not Repeat Offending". PLOS ONE. 8 (8) e71169. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...871169S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071169. PMC 3737138. PMID 23940711.

- ^ Anonymous (17 October 2016). "The legal limit". Mobility and transport – European Commission.

- ^ "Legal BAC limits by country". World Health Organization. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Gus Chan, The Plain Dealer (10 January 2011). "Cuyahoga County Council's finalists for boards of revision include employee with criminal past". Blog.cleveland.com. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Ogundipe, K. A.; Weiss, K. J. (2009). "Drunk driving, implied consent, and self-incrimination". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 37 (3): 386–291. PMID 19767505.

- ^ Sung, Hung-En (2016), "Alcohol and Crime", The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, American Cancer Society, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa039.pub2, ISBN 978-1-4051-6551-8

- ^ McMurran, Mary (3 October 2012). Alcohol-Related Violence: Prevention and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 337–338. ISBN 978-1-118-41106-3. Archived from the original on 5 September 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Alcohol 2018" (PDF). European Commission, Directorate General for Transport. February 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Yen, Hope; Krisher, Tom (9 November 2021). "Congress Mandates New Car Technology to Stop Drunken Driving". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "A lower drink-drive limit in Scotland is not linked to reduced road traffic accidents as expected". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 10 September 2019. doi:10.3310/signal-000815. S2CID 241723380.

- ^ Lewsey, Jim; Haghpanahan, Houra; Mackay, Daniel; McIntosh, Emma; Pell, Jill; Jones, Andy (June 2019). "Impact of legislation to reduce the drink-drive limit on road traffic accidents and alcohol consumption in Scotland: a natural experiment study". Public Health Research. 7 (12): 1–46. doi:10.3310/phr07120. ISSN 2050-4381. PMID 31241879.

- ^ Four in Ten Criminal Offenders Report Alcohol as a Factor in Violence: But Alcohol-Related Deaths and Consumption in Decline Archived 2011-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, April 5, 1998, United States Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- ^ DWI Offenders under Correctional Supervision Archived 2011-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, June 1999, United States Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- ^ "Impaired Driving: Get the Facts". CDC. 16 June 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

Further reading

- "Why drunk drivers may get behind the wheel." Mental Health Weekly Digest (2010). Web. 2 September 2010.

Drunk driving

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

History

Early regulations and precedents

The advent of the automobile in the late 19th century, with Karl Benz patenting the first practical motorwagen in 1886, facilitated rapid increases in road traffic by the early 1900s, heightening the visibility of accidents attributable to driver impairment from alcohol consumption. As vehicle numbers grew—reaching over 8,000 registered automobiles in the United States by 1900—contemporary reports began causally linking alcohol's effects on coordination and judgment to collisions, prompting initial calls for restrictions on intoxicated operation to mitigate public hazards. The first recorded arrest for drunk driving occurred on September 10, 1897, when London taxi driver George Smith crashed his cab into a building while intoxicated, establishing a legal precedent for prosecuting alcohol-impaired vehicle operation based on observed erratic behavior rather than chemical measurement.[11] This incident underscored the causal risk of alcohol exacerbating the novel dangers of motorized travel, influencing subsequent regulatory responses amid sparse traffic laws focused primarily on reckless conduct. In the United States, New York enacted the nation's first explicit statute against driving while intoxicated on August 5, 1910, making it a misdemeanor to operate a motor vehicle in an impaired state without specifying blood alcohol thresholds or testing protocols; enforcement relied on eyewitness testimony and physician examinations to determine intoxication.[12] This law directly responded to mounting accident data correlating alcohol use with fatalities, as early automotive adoption amplified the consequences of impaired decision-making on public roads.[13] European precedents predating World War I similarly extended prior statutes on public intoxication and vehicle control, such as the United Kingdom's 1872 Licensing Act prohibiting drunkenness while in charge of carriages or animals, which courts adapted to emerging automobiles by emphasizing sobriety for safe operation.[14] In Nordic countries, although dedicated driving laws emerged post-war in the 1920s, pre-1914 public safety ordinances tied sobriety requirements to hazardous activities, laying groundwork for recognizing alcohol's causal role in traffic mishaps as motorized vehicles proliferated.[15] These rudimentary measures prioritized empirical observations of impairment over quantitative standards, reflecting an initial focus on preventing foreseeable harms from alcohol's depressive effects amid the transition from horse-drawn to engine-powered transport.Emergence of scientific and legal standards

The transition from moralistic prohibitions against driving while intoxicated to empirically grounded legal standards began in the 1930s, driven by advancements in chemical testing and epidemiological research. In 1936, the National Safety Council established the Committee on Tests for Intoxication to standardize methods for detecting alcohol impairment, emphasizing objective measurement over subjective observation.[16] By 1938, the American Medical Association and National Safety Council jointly recommended a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) threshold of 0.15% as presumptive evidence of intoxication, based on early physiological studies linking alcohol levels to impaired coordination and judgment; this marked the first widespread adoption of quantifiable limits in U.S. jurisdictions, with states like Indiana enacting such statutes by 1939.[17] Post-World War II innovations further solidified scientific foundations for enforcement. In 1954, Robert F. Borkenstein, a professor at Indiana University and former state police captain, invented the Breathalyzer, a portable device using photochemical reactions to estimate BAC from breath samples, which facilitated rapid roadside testing and shifted reliance from blood draws to more practical field methods.[18] This tool's deployment in the late 1950s enabled broader data collection on alcohol's role in crashes. Concurrently, the Grand Rapids Study (1954–1959), led by Borkenstein and colleagues, analyzed over 5,000 drivers involved in accidents compared to control groups, demonstrating a exponential increase in relative crash risk starting at BAC levels as low as 0.05%, with risk multiplying over 25-fold at 0.15%; published in 1964, it provided causal evidence that alcohol impairs reaction time, vision, and decision-making in a dose-dependent manner, influencing global threshold-setting.[19] By the 1960s and 1970s, these findings spurred international efforts toward harmonized standards, moving beyond anecdotal enforcement. The World Health Organization, through expert committees since the 1950s, increasingly recognized alcohol as a primary modifiable factor in traffic fatalities, advocating for BAC limits informed by risk curves like those from Grand Rapids; this aligned with U.S. federal initiatives under the 1966 Highway Safety Act, which promoted data-driven state laws emphasizing measurable impairment over vague intoxication.[20] Such developments prioritized causal mechanisms—alcohol's disruption of neural processing—over prior punitive approaches, laying groundwork for per se laws where exceeding a BAC threshold constitutes offense regardless of observed behavior.[19]Advocacy movements and policy shifts

Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) was founded in September 1980 by Candace Lightner following the death of her 13-year-old daughter Cari, who was killed by a repeat drunk driver in California.[21] The organization rapidly expanded, advocating for stricter enforcement, higher penalties, and public awareness campaigns against impaired driving.[22] In 1982, President Ronald Reagan established the Presidential Commission on Drunk Driving via Executive Order 12358 on April 14, which included MADD representatives and aimed to heighten awareness and urge states to strengthen laws, including uniform blood alcohol concentration (BAC) standards and administrative license suspensions.[23] These efforts contributed to federal incentives for states to adopt a 0.08% BAC legal limit, with Congress passing the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century in 1998, which tied highway funding to compliance; by 2004, all states had enacted 0.08% per se laws following withholdings for non-compliant states starting in 2003.[24] Accompanying policy shifts included mandatory minimum sentences, ignition interlock requirements, and sobriety checkpoints, correlating with a reported 64% decline in alcohol-impaired driving fatalities per 100,000 population from 1982 to 2016, though causal attribution is complicated by concurrent factors such as widespread seatbelt mandates in the 1980s and improved vehicle safety technologies.[25] Responsibility.org, an industry-supported organization citing National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) data, attributes part of the reduction to enforcement enhancements, but independent analyses emphasize multifaceted interventions over singular advocacy-driven narratives.[26] In recent years, states have intensified measures for repeat offenders. California, for instance, implemented harsher mandatory minimum sentences in 2025, requiring at least 120 days in jail for third-time DUI convictions, alongside expanded ignition interlock device pilots for recidivists and those causing injury, set to continue through December 31, 2025.[27] Additionally, legislative actions in October 2025 aimed to close DUI loopholes by mandating interlocks for all offenders, drawing on evidence from over 30 states showing a 16% recidivism drop, reflecting ongoing policy evolution toward deterrence-focused reforms despite debates over enforcement efficacy.[28]Definition and Terminology

Core definitions

Drunk driving entails operating a motor vehicle while the driver's cognitive and psychomotor faculties are diminished by alcohol ingestion, compromising safe vehicle control through slowed reaction times, impaired judgment, and reduced coordination. This impairment stems from alcohol's pharmacological action as a central nervous system depressant, which disrupts neural signaling and elevates crash risk proportionally to blood alcohol concentration (BAC), with empirical models showing relative risk doubling at 0.05% BAC and rising exponentially thereafter.[29] Legal definitions distinguish between impairment-based offenses, requiring evidence of faculties substantially lessened to unsafe degrees, and per se violations, which impose strict liability upon exceeding predefined BAC thresholds irrespective of observable effects.[30] Common terminology includes DUI (Driving Under the Influence), emphasizing influence causing impairment; DWI (Driving While Intoxicated), often denoting per se BAC exceedance with presumed intoxication; and OWI (Operating While Intoxicated), extending to vehicle operation beyond active driving. Alcohol-impaired driving contributes to verifiable harm, accounting for approximately 30% of U.S. traffic fatalities, with 12,429 deaths in crashes involving drivers at BAC ≥0.08 g/dL in 2023.[1] [31] Despite this, the phenomenon occurs amid millions of self-reported alcohol-impaired driving instances annually, as surveys indicate over 18 million such episodes among U.S. drivers aged 16 and older, underscoring that while relative risk per mile driven surges with alcohol, absolute crash incidence remains rare per episode due to baseline low accident probabilities in sober driving.[32] This disparity highlights the causal role of impairment in elevating danger without implying inevitability, as population-scale fatalities arise from aggregated exposure rather than universal outcomes per impaired trip.[29]