Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

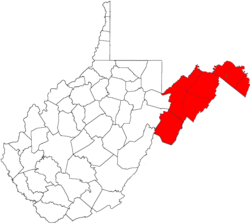

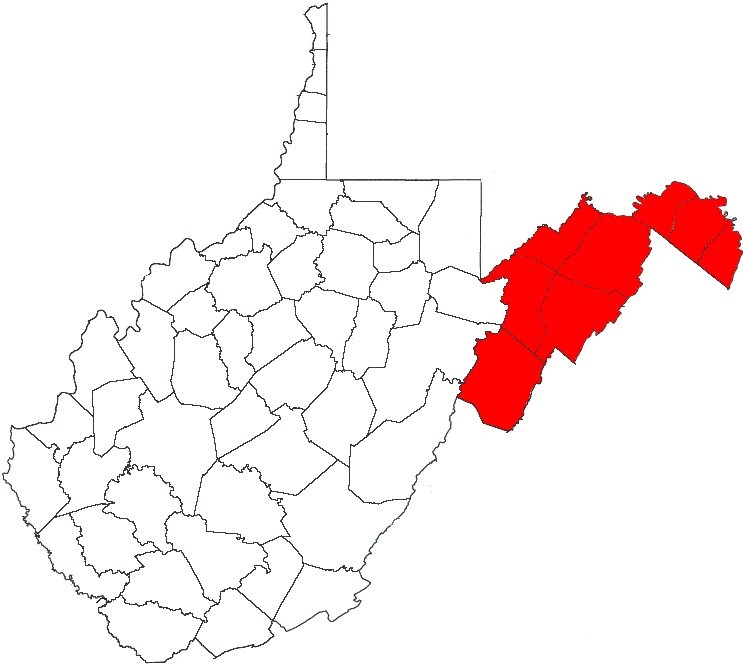

Eastern panhandle of West Virginia

View on Wikipedia

The eastern panhandle is one of the two panhandles in the U.S. state of West Virginia; the other is the northern panhandle. It is a small stretch of territory in the northeast of the state, bordering Maryland and Virginia. Some sources and regional associations only identify the eastern panhandle as being composed of Morgan, Berkeley, and Jefferson Counties.[3] Berkeley and Jefferson Counties are geographically located in the Shenandoah Valley. West Virginia is the only U.S. state with two panhandles.

Key Information

History

[edit]Berkeley, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, and Morgan Counties were part of the Unionist state of West Virginia created in 1863. Shortly after West Virginia gained statehood, Mineral and Grant Counties were created from Hampshire and Hardy in 1866.

The eastern panhandle includes West Virginia's oldest chartered towns (1762) of Romney and Shepherdstown. The panhandle also includes West Virginia's two oldest counties: Hampshire (1753) and Berkeley (1772). West Virginia's historically most famous towns, Harpers Ferry and Charles Town, are at the eastern end of the eastern panhandle. Harpers Ferry is the easternmost town in West Virginia.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, now CSX, runs through the panhandle. Until 1861, Harpers Ferry was the site of a U.S. armory (weapons factory), briefly captured by John Brown during his famous raid. The strategic nature of the area influenced its inclusion in West Virginia by the Union Congress.

There has been talk about certain counties in the eastern panhandle rejoining Virginia, due primarily to poor economic conditions and perceived neglect from the state government. In 2011, West Virginia state delegate Larry Kump sponsored legislation to allow Morgan, Berkeley, and Jefferson Counties to rejoin Virginia by popular vote.[4] The bill did not pass.

Geography

[edit]The eastern panhandle includes both West Virginia's highest and lowest elevations above sea level: Spruce Knob, 4,863 feet (1,482 m), in Pendleton and Harpers Ferry, 240 feet (73 m), in Jefferson on the Potomac River. The region is separated from the remainder of the state by the Allegheny Front, which separates the Mississippi watershed from that of Chesapeake Bay.

The counties in the eastern panhandle are:[5]

- Berkeley

- Grant

- Hampshire

- Hardy

- Jefferson

- Mineral

- Morgan

- Pendleton County is included in some definitions.[6]

A short stretch of West Virginia Route 9 west of Berkeley Springs provides the only road connection between Berkeley Springs and points east to the rest of state without having to cross state lines.

Population

[edit]According to the 2010 census, the eight counties of the eastern panhandle had a combined population of 261,041, giving the region 11.75% of West Virginia's population.[7] Berkeley County is the panhandle's most populous county, with a census 104,169 residents (2010). Berkeley also includes the panhandle's largest city, Martinsburg, with a 2010 census population of 17,227.[8]

Housing growth

[edit]The eastern panhandle is West Virginia's fastest-growing region in terms of population and housing. In July 2005, the United States Census Bureau released a list of the top 100 counties according to housing growth. Berkeley County grew 3.95 percent, from 36,365 housing units in 2003 to 37,802 units in 2004. That growth rate was 86th in the nation among the 3,143 United States counties. Jefferson County was not far behind at 88th in the nation. It grew 3.94 percent from 19,381 housing units in 2003 to 20,144 units in 2004.

Largest municipalities

[edit]The majority of the eastern panhandle's growing residential developments are located outside city and town boundaries and are not included in the city or town's official population.

| City | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 | 1980 | 1970 | County |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martinsburg | 17,227 | 14,972 | 14,073 | 13,063 | 14,626 | Berkeley |

| Keyser | 5,439 | 5,303 | 5,870 | — | 6,586 | Mineral |

| Ranson | 3,957 | 2,951 | 2,890 | — | 2,189 | Jefferson |

| Charles Town | 5,259 | 2,907 | 3,122 | — | 3,023 | Jefferson |

| Petersburg | 2,467 | 2,423 | 2,360 | — | 2,177 | Grant |

| Moorefield | 2,544 | 2,375 | 2,148 | — | 2,124 | Hardy |

| Romney | 1,848 | 1,940 | 1,966 | — | 2,364 | Hampshire |

| Shepherdstown | 1,734 | 803 | 1,287 | — | 1,688 | Jefferson |

| Bolivar | 1,045 | 1,045 | 1,013 | — | 943 | Jefferson |

| Piedmont | 876 | 1,014 | 1,094 | — | 1,763 | Mineral |

NOTE: This list does not include the unincorporated census-designated places of Inwood (pop. 2,954) and Fort Ashby (pop. 1,380). The U.S. Census Bureau does not release estimates for CDPs. The population figures listed are from the 2010 census.

Statistical areas

[edit]Several counties in the eastern panhandle are part of metropolitan, micropolitan, and consolidated metropolitan statistical areas defined by the United States Office of Management and Budget.

| MSA/CMSA | Population (2000) | WV Counties |

|---|---|---|

| Cumberland, MD-WV MSA | 102,008 | Mineral |

| Hagerstown-Martinsburg, MD-WV MSA | 222,771 | Berkeley, Morgan |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV MSA | 4,796,183 | Jefferson |

| Washington-Baltimore, DC-MD-VA-WV CSA | 7,538,385 | Berkeley, Jefferson |

| Winchester, VA-WV MSA | 102,997 | Hampshire |

County information

[edit]| County | Named For | Founded | Seat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berkeley | Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt | February 1772 | Martinsburg |

| Grant | Ulysses S. Grant | February 14, 1866 | Petersburg |

| Hampshire | County of Hampshire, England | December 13, 1753 | Romney |

| Hardy | Samuel Hardy | December 10, 1785 | Moorefield |

| Jefferson | Thomas Jefferson | January 8, 1801 | Charles Town |

| Mineral | minerals located in the county | February 1, 1866 | Keyser |

| Morgan | General Daniel Morgan | February 9, 1820 | Berkeley Springs |

| Pendleton | Edmund Pendleton | December 4, 1787 | Franklin |

Places of worship

[edit]- Hampshire County is home to two religious learning centers: the Buddhist Bhavana Society Forest Monastery and Retreat Center in High View and the Global Country of World Peace's Transcendental Meditation Learning Center and Retreat in Three Churches.

Potomac Highlands

[edit]Grant, Hampshire, Hardy, Mineral, and Pendleton Counties belong to the geographical region of West Virginia known as the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "United States Summary: 2010, Population and Housing Unit Counts, 2010 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. September 2012. pp. V–2, 1 & 41 (Tables 1 & 18). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ "Population, Population Change, and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019 (NST-EST2019-alldata)". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ "WV Dept. of Commerce". Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Jenni Vincent (January 25, 2011). "Secession bill planned to 'stir pot'". The Journal. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ "Eastern Panhandle Modern Map". The West Virginia Encyclopedia. West Virginia Humanities Council. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ Williams, B.H.; Fridley, H.M (1923). Soil Survey of Hardy and Pendleton Counties, West Virginia. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ "Eastern Panhandle". The West Virginia Encyclopedia. West Virginia Humanities Council. November 20, 2010. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ "Martinsburg (city), West Virginia". State and County QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.