Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stonewall Jackson

View on Wikipedia

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general and military officer who served during the American Civil War. He played a prominent role in nearly all military engagements in the eastern theater of the war until his death. Military historians regard him as one of the most gifted tactical commanders in U.S. history.[2]

Key Information

Born in what was then part of Virginia (now in West Virginia), Jackson received an appointment to the United States Military Academy, graduating in the class of 1846. He served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Chapultepec. From 1851 to 1861, he taught at the Virginia Military Institute.

When Virginia seceded from the United States in May 1861 after the Battle of Fort Sumter, Jackson joined the Confederate States Army. He distinguished himself commanding a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run in July, providing crucial reinforcements and beating back a fierce Union assault. Thus Barnard E. Bee compared him to a "stone wall", which became his enduring nickname.[3]

Jackson performed exceptionally well in various campaigns over the next two years. On May 2, 1863, he was accidentally shot by Confederate pickets.[4] He lost his left arm to amputation. Weakened by his wounds, he died of pneumonia eight days later. Jackson's death proved a severe setback for the Confederacy. After his death, his military exploits developed a legendary quality, becoming an important element of the pseudohistorical ideology of the "Lost Cause".[5]

Ancestry

[edit]Thomas Jonathan Jackson[6] was a great-grandson of John Jackson (1715/1719–1801) and Elizabeth Cummins (also known as Elizabeth Comings and Elizabeth Needles) (1723–1828). John Jackson was an Ulster-Scots Protestant from Coleraine, County Londonderry, in the north of Ireland. While living in London, England, he was convicted of the capital crime of larceny for stealing £170 (equivalent to £33,781 in 2023); the judge at the Old Bailey sentenced him to seven years penal transportation. Elizabeth, a strong, blonde woman almost 6 feet (180 cm) tall, born in London, was also convicted of felony larceny in an unrelated case for stealing 19 pieces of silver, jewelry, and fine lace, and received a similar sentence. They both were transported on the merchant ship Litchfield, which departed London in May 1749 with 150 convicts. John and Elizabeth met on board and were in love by the time the ship arrived at Annapolis, Maryland. Although they were sent to different locations in Maryland for their bond service, the couple married in July 1755.[7]

The family migrated west across the Blue Ridge Mountains to settle near Moorefield, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1758. In 1770, they moved farther west to the Tygart Valley. They began to acquire large parcels of virgin farming land near the present-day town of Buckhannon, including 3,000 acres (12 km2) in Elizabeth's name. John and his two teenage sons were early recruits for the American Revolutionary War, fighting in the Battle of Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780; John finished the war as captain and served as a lieutenant of the Virginia militia after 1787. While the men were in the Army, Elizabeth converted their home to a haven, "Jackson's Fort", for refugees from Indian attacks.[8]

John and Elizabeth had eight children. Their second son was Edward Jackson (1759–1828), and Edward's third son[9] was Jonathan Jackson, Thomas's father.[10] Jonathan's mother died on April 17, 1796. Three years later, on October 13, 1799, his father married Elizabeth Wetherholt, and they had nine more children.[11][12]

Early life

[edit]Early childhood

[edit]Thomas Jackson was born in the town of Clarksburg, Harrison County, Virginia, on January 21, 1824. He was the third child of Julia Beckwith (née Neale) Jackson (1798–1831) and Jonathan Jackson (1790–1826), an attorney. Both of Jackson's parents were natives of Virginia. The family already had two young children and were living in Clarksburg, in what is now West Virginia, when Thomas was born. He was named for his maternal grandfather. There is some dispute about the actual location of Jackson's birth. A historical marker on the floodwall in Parkersburg, West Virginia, claims that he was born in a cabin near that spot when his mother was visiting her parents who lived there. There are writings which indicate that in Jackson's early childhood, he was called "The Real Macaroni", though the origin of the nickname and whether it really existed are unclear.[13]

Thomas's sister Elizabeth (age six) died of typhoid fever on March 6, 1826, with two-year-old Thomas at her bedside. His father also died of typhoid fever on March 26, 1827, after nursing his daughter. Jackson's mother gave birth to his sister Laura Ann the day after Jackson's father died.[14] Julia Jackson thus was widowed at 28 and was left with much debt and three young children (including the newborn). She sold the family's possessions to pay the debts. She declined family charity and moved into a small rented one-room house. Julia took in sewing and opened a private school to support herself and her three young children for about four years.

In 1830, Julia Neale Jackson remarried, against the wishes of her friends. Her new husband, Captain Blake B. Woodson,[15] an attorney, did not like his stepchildren. Warren, Julia's eldest son, moved to live with his uncle Alfred Neale near Parkersburg, and at the age of sixteen, he was hired to teach in Upshur County. Julia moved to Fayette County with her other two children, Thomas and Laura. Julia remained in such poor health, and caring for the children was such a strain on her strength, that she agreed to let their Grandmother Jackson take them to her home in Lewis County, about four miles north of Weston, where she lived with her unmarried daughters and sons. One of these sons was sent to Fayette County to care for the children by the grandmother. When he arrived and the purpose of his visit was revealed, there was quite a commotion among the children, who were very reluctant to leave their mother. Thomas, now six years old, slipped away to the nearby woods, where he hid, only returning to the house at nightfall. After a day or two of coaxing and numerous bribes, the uncle finally persuaded the children to make the trip, which took several days, with the help of their mother. When they arrived at their destination, they became the pets of an indulgent grandmother, two maiden aunts, and several bachelor uncles, all of whom were known for their great kindness of heart and strong family attachment. Thomas and Laura were indulged in every way, and to an extent well calculated to spoil them. In August 1835, Thomas and Laura's grandmother died.

The following year, after giving birth to Thomas's half-brother Willam Wirt Woodson, Julia died of complications, leaving her three older children orphaned.[16] Julia was buried in an unmarked grave in a homemade coffin in Westlake Cemetery along the James River and Kanawha Turnpike in Fayette County within the corporate limits of present-day Ansted, West Virginia.

Working and teaching at Jackson's Mill

[edit]

As their mother's health continued to fail, Jackson and his sister Laura Ann were sent to live with their half-uncle, Cummins Jackson, who owned a grist mill in Jackson's Mill (near present-day Weston in Lewis County in central West Virginia). Their older brother, Warren, went to live with other relatives on his mother's side of the family, but he later died of tuberculosis in 1841 at the age of twenty. Thomas and Laura Ann returned from Jackson's Mill in November 1831 to be at their dying mother's bedside. They spent four years together at the Mill before being separated—Laura Ann was sent to live with her mother's family, Thomas to live with his Aunt Polly (his father's sister) and her husband, Isaac Brake, on a farm four miles from Clarksburg. Thomas was treated by Brake as an outsider and, having suffered verbal abuse for over a year, ran away from the family. When his cousin in Clarksburg urged him to return to Aunt Polly's, he replied, "Maybe I ought to, ma'am, but I am not going to." He walked eighteen miles through mountain wilderness to Jackson's Mill, where he was welcomed by his uncles and he remained there for the following seven years.[17]

Cummins Jackson was strict with Thomas, who looked up to Cummins as a schoolteacher. Jackson helped around the farm, tending sheep with the assistance of a sheepdog, driving teams of oxen and helping harvest wheat and corn. Formal education was not easily obtained, but he attended school when and where he could. Much of Jackson's education was self-taught. He once made a deal with one of his uncle's slaves to provide him with pine knots in exchange for reading lessons; Thomas would stay up at night reading borrowed books by the light of those burning pine knots. Virginia law forbade teaching a slave, free black or mulatto to read or write; nevertheless, Jackson secretly taught the slave, as he had promised. Once literate, the young slave fled to Canada via the Underground Railroad.[18] In his later years at Jackson's Mill, Thomas served as a schoolteacher.

Brother against sister

[edit]The Civil War has sometimes been referred to as a war of "brother against brother", but in the case of the Jackson family, it was brother against sister. Laura Jackson Arnold was close to her brother Thomas until the Civil War period. As the war loomed, she became a staunch Unionist in a somewhat divided Harrison County. She was so strident in her beliefs that she expressed mixed feelings upon hearing of Thomas's death. One Union officer said that she seemed depressed at hearing the news, but her Unionism was stronger than her family bonds. In a letter, he wrote that Laura had said that she "would rather know that he was dead than to have him a leader in the rebel army". Her Union sentiment also estranged her later from her husband, Jonathan Arnold.[19]

Early military career

[edit]West Point

[edit]In 1842, Jackson was accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Because of his inadequate schooling, he had difficulty with the entrance examinations and began his studies at the bottom of his class. Displaying a dogged determination that was to characterize his life, he became one of the hardest working cadets in the academy, and moved steadily up the academic rankings. Jackson graduated 17th out of 59 students in the Class of 1846.[20] General Daniel Harvey Hill later remembered that Jackson's peers at West Point had said of Jackson, "If the course had been one year longer he would have graduated at the head of his class".[21]

U.S. Army and the Mexican War

[edit]Jackson began his United States Army career as a second lieutenant in Company K of the 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment. His unit proceeded through Pennsylvania, down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to New Orleans, and from there the troops embarked for Point Isabel, Texas, from where they were sent to fight in the Mexican–American War. Jackson's unit was directed to report to General Taylor and proceed immediately via Matamoros and Camargo to Monterey and then to Saltillo. Prior to the Battle of Buena Vista, Lieutenant Jackson's unit was ordered to withdraw from General Taylor's army and march to the mouth of the Rio Grande, where they would be transferred to Veracruz. He served at the Siege of Veracruz and the battles of Contreras, Chapultepec, and Mexico City, eventually earning two brevet promotions, and the regular army rank of first lieutenant. It was in Mexico that Jackson first met Robert E. Lee.

During the Battle of Chapultepec on September 13, 1847, he refused what he felt was a "bad order" to withdraw his troops. Confronted by his superior, he explained his rationale, claiming withdrawal was more hazardous than continuing his overmatched artillery duel. His judgment proved correct, and a relieving brigade was able to exploit the advantage Jackson had broached. In contrast to this display of strength of character, he obeyed what he also felt was a "bad order" when he raked a civilian throng with artillery fire after the Mexican authorities failed to surrender Mexico City at the hour demanded by the U.S. forces.[22] The former episode, and later aggressive action against the retreating Mexican army, earned him field promotion to the brevet rank of major.[20]

After the war, Jackson was briefly assigned to units in New York, and later to Florida during the Second Interbellum of the Seminole Wars, during which the Americans were attempting to force the remaining Seminoles to move west. He was stationed briefly at Fort Casey before being named second-in-command at Fort Meade, a small fort about thirty miles south of Tampa.[23] His commanding officer was Major William H. French. Jackson and French disagreed often, and filed numerous complaints against each other. Jackson stayed in Florida less than a year.[24]

Lexington and the Virginia Military Institute

[edit]

In the spring of 1851,[25] Jackson accepted a newly created teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). He became Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy, or Physics, and Instructor of Artillery.

Jackson was disliked as a teacher, with his students nicknaming him "Tom Fool", believing that Jackson "could never be anything more than a martinet colonel, half soldier and half preacher".[26] He memorized his lectures and then recited them to the class. Students who came to ask for help were given the same explanation as before. If a student asked for help a second time, Jackson simply repeated the explanation slower and more deliberately.[27] In 1856, a group of alumni attempted to have Jackson removed from his position.[28]

The founder of VMI and one of its first two faculty members was John Thomas Lewis Preston. Preston's second wife, Margaret Junkin Preston, was the sister of Jackson's first wife, Elinor. In addition to working together on the VMI faculty, Preston taught Sunday School with Jackson and served on his staff during the Civil War.[29]

Slavery

[edit]

Jackson was not known to the white inhabitants of Lexington, instead mostly being known by many of the African Americans in town, both slaves and free blacks.[30] In 1855, he organized Sunday School classes for blacks at the Presbyterian Church, as part of a broader program of evangelizing pro-slavery theology to enslaved people following Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion.[31] His second wife, Mary Anna Jackson, taught with Jackson, as "he preferred that my labors should be given to the colored children, believing that it was more important and useful to put the strong hand of the Gospel under the ignorant African race, to lift them up".[32] The pastor, Dr. William Spottswood White, described the relationship between Jackson and his Sunday afternoon students: "In their religious instruction he succeeded wonderfully. His discipline was systematic and firm, but very kind. ... His servants reverenced and loved him, as they would have done a brother or father. ... He was emphatically the black man's friend." He addressed his students by name and they referred to him as "Marse Major".[33]

Jackson owned six slaves in the late 1850s. Three (Harriet, nicknamed "Hetty", and her teenage sons Cyrus and George) were received as part of the dowry at his marriage to Mary Anna Jackson.[34] Another slave, Albert, requested that Jackson purchase him and allow him to work for his freedom; he was employed as a waiter in one of the Lexington hotels and Jackson rented him to VMI between 1858 and 1860. He had likely bought his freedom by 1863.[35] Amy also requested that Jackson purchase her from a public slave auction and she served the family as a cook and housekeeper, before dying in the fall of 1861.[36] The sixth, Emma, was a four-year-old orphan with a learning disability, accepted by Jackson from an aged widow and presented to Anna as a welcome-home gift.[37] After Jackson was shot at Chancellorsville, a slave "Jim Lewis, had stayed with Jackson in the small house as he lay dying".[38] Jackson and Anna likely sold two of these slaves in 1857 to pay for a larger house after their wedding.[39] In her 1895 memoir, Anna described Jackson as a master providing "firm guidance and restraint",[40] who would "punish for first offenses" and "make such an impression that the offense would not be repeated".[41] Jackson left few indications of his private views on slavery, but he largely accepted it as a divinely sanctioned institution, and his actions were typical for white slaveowners of his era.[42][43][44]

After the outbreak of the Civil War, most white men in Lexington joined the Confederate army, leaving women to manage slave-holding households. This led to greatly increased resistance to enslavement in much of the South, and Anna found the household difficult to control; upon Stonewall's advice, she sold or hired out all of the slaves except Hetty before moving back to Lincoln County, North Carolina.[45] Harriet, George, Cyrus, and Emma eventually settled nearby, with Harriet (later Harriet Graham Jackson) living until 1911 and George (later George Washington Jackson Sr.) dying in 1920. Their descendants continue to reside in Lincoln County.[46]

In the Maryland campaign of 1862, Jackson's command captured over 1200 contrabands, or escaped slaves, in Harpers Ferry, forcibly returning them to slaveowners or impressing them as laborers for the Army of Northern Virginia. Southern newspapers reported this as a common practice in Confederate military operations.[47]

Marriages and family life

[edit]

While an instructor at VMI in 1853, Thomas Jackson married Elinor "Ellie" Junkin, whose father, George Junkin, was president of Washington College (later named Washington and Lee University) in Lexington. An addition was built onto the president's residence for the Jacksons, and when Robert E. Lee became president of Washington College he lived in the same home, now known as the Lee–Jackson House.[48] Ellie gave birth to a stillborn son on October 22, 1854, experiencing a hemorrhage an hour later that proved fatal.[49]

After a tour of Europe, Jackson married again, in 1857. Mary Anna Morrison was from North Carolina, where her father was the first president of Davidson College. Her sister, Isabella Morrison, was married to Daniel Harvey Hill. Mary Anna had a daughter named Mary Graham on April 30, 1858, but the baby died less than a month later. Another daughter was born in 1862, shortly before her father's death. The Jacksons named her Julia Laura, after his mother and sister.

Jackson purchased the only house he ever owned while in Lexington. Built in 1801, the brick town house at 8 East Washington Street was purchased by Jackson in 1859. He lived in it for two years before being called to serve in the Confederacy. Jackson never returned to his home.

John Brown raid aftermath

[edit]In November 1859, at the request of the governor of Virginia, Major William Gilham led a contingent of the VMI Cadet Corps to Charles Town to provide an additional military presence at the hanging of militant abolitionist John Brown on December 2, following his raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry on October 16. Major Jackson was placed in command of the artillery, consisting of two howitzers manned by twenty-one cadets.

Civil War

[edit]

In April 1861, after Virginia seceded from the Union and as the American Civil War broke out, Jackson was ordered by the Governor of Virginia to report with the VMI cadet corps to Richmond and await further orders. Upon arrival, Jackson was appointed a Major of Engineers in the Provisional Army of Virginia, which was a short lived force commanded by Robert E. Lee, prior to Virginia fully augmenting into forces of the Confederacy. After Jackson protested such a low rank, the Virginia Governor appointed him a Colonel of Virginia Infantry which in May 1861 was augmented to a Colonel in the Confederate Army. Jackson then became a drill master for some of the many new recruits in the Confederate Army.

On April 27, 1861, Virginia Governor John Letcher ordered Colonel Jackson to take command at Harpers Ferry, where he would assemble and command the unit which later gained fame as the "Stonewall Brigade", consisting of the 2nd, 4th, 5th, 27th, and 33rd Virginia Infantry regiments. These units were from the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia, where Jackson located his headquarters throughout the first two years of the war, as well as counties in western Virginia.[50] Jackson became known for his relentless drilling of his troops; he believed discipline was vital to success on the battlefield. Following raids on the B&O Railroad on May 24, he was promoted to brigadier general on June 17, 1861. Jackson continued to wear a blue Union Army uniform up to this point, having only access to his old VMI major's jacket, and would not be issued with a gray Confederate uniform until 1862.[51]

First Battle of Bull Run

[edit]

Jackson rose to prominence and earned his most famous nickname at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas) on July 21, 1861. As the Confederate lines began to crumble under heavy Union assault, Jackson's brigade provided crucial reinforcements on Henry House Hill, demonstrating the discipline he instilled in his men. While under heavy fire for several continuous hours, Jackson received a wound, breaking the middle finger of his left hand about midway between the hand and knuckle, the ball passing on the side next to the index finger. The troops of South Carolina, commanded by Gen. Barnard E. Bee had been overwhelmed, and he rode up to Jackson in despair, exclaiming, "They are beating us back!" "Then," said Jackson, "we will give them the bayonet!" As he rode back to his command, Bee exhorted his own troops to re-form by shouting, "There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians!"[52] There is some controversy over Bee's statement and intent, which could not be clarified because he was killed almost immediately after speaking and none of his subordinate officers wrote reports of the battle. Major Burnett Rhett, chief of staff to General Joseph E. Johnston, claimed that Bee was angry at Jackson's failure to come immediately to the relief of Bee's and Francis S. Bartow's brigades while they were under heavy pressure. Those who subscribe to this opinion believe that Bee's statement was meant to be pejorative: "Look at Jackson standing there like a stone wall!"[53]

Regardless of the controversy and the delay in relieving Bee, Jackson's brigade, which would thenceforth be known as the Stonewall Brigade, stopped the Union assault and suffered more casualties than any other Southern brigade that day; Jackson has since then been generally known as Stonewall Jackson.[54] During the battle, Jackson displayed a gesture common to him and held his left arm skyward with the palm facing forward – interpreted by his soldiers variously as an eccentricity or an entreaty to God for success in combat. His hand was struck by a bullet or a piece of shrapnel and he suffered a small loss of bone in his middle finger. He refused medical advice to have the finger amputated.[55] After the battle, Jackson was promoted to major general (October 7, 1861)[51] and given command of the Valley District, with headquarters in Winchester.

Valley Campaign

[edit]In the spring of 1862, Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac approached Richmond from the southeast in the Peninsula Campaign. Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's large corps was poised to hit Richmond from the north, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's army threatened the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson was ordered by Richmond to operate in the Valley to defeat Banks's threat and prevent McDowell's troops from reinforcing McClellan.

Jackson possessed the attributes to succeed against his poorly coordinated and sometimes timid opponents: a combination of great audacity, excellent knowledge and shrewd use of the terrain, and an uncommon ability to inspire his troops to great feats of marching and fighting.

The campaign started with a tactical defeat at Kernstown on March 23, 1862, when faulty intelligence led him to believe he was attacking a small detachment. But it became a strategic victory for the Confederacy, because his aggressiveness suggested that he possessed a much larger force, convincing President Abraham Lincoln to keep Banks' troops in the Valley and McDowell's 30,000-man corps near Fredericksburg, subtracting about 50,000 soldiers from McClellan's invasion force. As it transpired, it was Jackson's only defeat in the Valley.

By adding Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's large division and Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's small division, Jackson increased his army to 17,000 men. He was still significantly outnumbered, but attacked portions of his divided enemy individually at McDowell, defeating both Brig. Gens. Robert H. Milroy and Robert C. Schenck. He defeated Banks at Front Royal and Winchester, ejecting him from the Valley. Lincoln decided that the defeat of Jackson was an immediate priority (though Jackson's orders were solely to keep Union forces occupied and away from Richmond). He ordered Irvin McDowell to send 20,000 men to Front Royal and Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont to move to Harrisonburg. If both forces could converge at Strasburg, Jackson's only escape route up the Valley would be cut.

After a series of maneuvers, Jackson defeated Frémont's command at Cross Keys and Brig. Gen. James Shields at Port Republic on June 8–9. Union forces were withdrawn from the Valley.

It was a classic military campaign of surprise and maneuver. Jackson pressed his army to travel 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days of marching and won five significant victories with a force of about 17,000 against a combined force of 60,000. Stonewall Jackson's reputation for moving his troops so rapidly earned them the oxymoronic nickname "foot cavalry". He became the most celebrated soldier in the Confederacy (until he was eventually eclipsed by Lee) and lifted the morale of the Southern public.

Peninsula

[edit]McClellan's Peninsula Campaign toward Richmond stalled at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31 and June 1. After the Valley Campaign ended in mid-June, Jackson and his troops were called to join Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia in defense of the capital. By using a railroad tunnel under the Blue Ridge Mountains and then transporting troops to Hanover County on the Virginia Central Railroad, Jackson and his forces made a surprise appearance in front of McClellan at Mechanicsville. Reports had last placed Jackson's forces in the Shenandoah Valley; their presence near Richmond added greatly to the Union commander's overestimation of the strength and numbers of the forces before him. This proved a crucial factor in McClellan's decision to re-establish his base at a point many miles downstream from Richmond on the James River at Harrison's Landing, essentially a retreat that ended the Peninsula Campaign and prolonged the war almost three more years.

Jackson's troops served well under Lee in the series of battles known as the Seven Days Battles, but Jackson's own performance in those battles is generally considered to be poor.[56] He arrived late at Mechanicsville and inexplicably ordered his men to bivouac for the night within clear earshot of the battle. He was late at Savage's Station. At White Oak Swamp he failed to employ fording places to cross White Oak Swamp Creek, attempting for hours to rebuild a bridge, which limited his involvement to an ineffectual artillery duel and a missed opportunity to intervene decisively at the Battle of Glendale, which was raging nearby. At Malvern Hill Jackson participated in the futile, piecemeal frontal assaults against entrenched Union infantry and massed artillery, and suffered heavy casualties (but this was a problem for all of Lee's army in that ill-considered battle). The reasons for Jackson's sluggish and poorly coordinated actions during the Seven Days are disputed, although a severe lack of sleep after the grueling march and railroad trip from the Shenandoah Valley was probably a significant factor. Both Jackson and his troops were completely exhausted. An explanation for this and other lapses by Jackson was tersely offered by his colleague and brother in-law General Daniel Harvey Hill: "Jackson's genius never shone when he was under the command of another."[57]

Second Bull Run to Fredericksburg

[edit]

The military reputations of Lee's corps commanders are often characterized as Stonewall Jackson representing the audacious, offensive component of Lee's army, whereas his counterpart, James Longstreet, more typically advocated and executed defensive strategies and tactics. Jackson has been described as the army's hammer, Longstreet its anvil.[58] In the Northern Virginia Campaign of August 1862 this stereotype did not hold true. Longstreet commanded the Right Wing (later to become known as the First Corps) and Jackson commanded the Left Wing. Jackson started the campaign under Lee's orders with a sweeping flanking maneuver that placed his corps into the rear of Union Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia. The Hotchkiss journal shows that Jackson, most likely, originally conceived the movement. In the journal entries for March 4 and 6, 1863, General Stuart tells Hotchkiss that "Jackson was entitled to all the credit" for the movement and that Lee thought the proposed movement "very hazardous" and "reluctantly consented" to the movement.[59] At Manassas Junction, Jackson was able to capture all of the supplies of the Union Army depot. Then he had his troops destroy all of it, for it was the main depot for the Union Army. Jackson then retreated and then took up a defensive position and effectively invited Pope to assault him. On August 28–29, the start of the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas), Pope launched repeated assaults against Jackson as Longstreet and the remainder of the army marched north to reach the battlefield.

On August 30, Pope came to believe that Jackson was starting to retreat, and Longstreet took advantage of this by launching a massive assault on the Union army's left with over 25,000 men. Although the Union troops put up a furious defense, Pope's army was forced to retreat in a manner similar to the embarrassing Union defeat at First Bull Run, fought on roughly the same battleground.

When Lee decided to invade the North in the Maryland Campaign, Jackson took Harpers Ferry, then hastened to join the rest of the army at Sharpsburg, Maryland, where they fought McClellan in the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg). Antietam was primarily a defensive battle against superior odds, although McClellan failed to exploit his advantage. Jackson's men bore the brunt of the initial attacks on the northern end of the battlefield and, at the end of the day, successfully resisted a breakthrough on the southern end when Jackson's subordinate, Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill, arrived at the last minute from Harpers Ferry. The Confederate forces held their position, but the battle was extremely bloody for both sides, and Lee withdrew the Army of Northern Virginia back across the Potomac River, ending the invasion. On October 10, Jackson was promoted to lieutenant general, being ranked just behind Lee and Longstreet and his command was redesignated the Second Corps.

Before the armies camped for winter, Jackson's Second Corps held off a strong Union assault against the right flank of the Confederate line at the Battle of Fredericksburg, in what became a Confederate victory. Just before the battle, Jackson was delighted to receive a letter about the birth of his daughter, Julia Laura Jackson, on November 23.[60] Also before the battle, Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart, Lee's dashing and well-dressed cavalry commander, presented to Jackson a fine general's frock coat that he had ordered from one of the best tailors in Richmond. Jackson's previous coat was threadbare and colorless from exposure to the elements, its buttons removed by admiring ladies. Jackson asked his staff to thank Stuart, saying that although the coat was too handsome for him, he would cherish it as a souvenir. His staff insisted that he wear it to dinner, which caused scores of soldiers to rush to see him in uncharacteristic garb. Jackson was so embarrassed with the attention that he did not wear the new uniform for months.[61]

Chancellorsville

[edit]At the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Army of Northern Virginia faced a serious threat by the Army of the Potomac, led by its new commanding general, Major General Joseph Hooker. Lee decided to employ a risky tactic to take the initiative and offensive away from Hooker's new southern thrust – he decided to divide his forces. Jackson and his entire corps went on an aggressive flanking maneuver to the right of the Union lines. While riding with his infantry in a wide berth well south and west of the Federal line of battle, Jackson employed Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry to provide for better reconnaissance regarding the exact location of the Union right and rear. The results were far better than even Jackson could have hoped. Fitzhugh Lee found the entire right side of the Federal lines in the middle of open field, guarded merely by two guns that faced westward, as well as the supplies and rear encampments. The men were eating and playing games in carefree fashion, completely unaware that an entire Confederate corps was less than a mile away. What happened next is given in Fitzhugh Lee's own words:[citation needed]

So impressed was I with my discovery, that I rode rapidly back to the point on the Plank road where I had left my cavalry, and back down the road Jackson was moving, until I met "Stonewall" himself. "General", said I, "if you will ride with me, halting your column here, out of sight, I will show you the enemy's right, and you will perceive the great advantage of attacking down the Old turnpike instead of the Plank road, the enemy's lines being taken in reverse. Bring only one courier, as you will be in view from the top of the hill." Jackson assented, and I rapidly conducted him to the point of observation. There had been no change in the picture. I only knew Jackson slightly. I watched him closely as he gazed upon Howard's troops. It was then about 2 pm. His eyes burned with a brilliant glow, lighting up a sad face. His expression was one of intense interest, his face was colored slightly with the paint of approaching battle, and radiant at the success of his flank movement. To the remarks made to him while the unconscious line of blue was pointed out, he did not reply once during the five minutes he was on the hill, and yet his lips were moving. From what I have read and heard of Jackson since that day, I know now what he was doing then. Oh! "beware of rashness", General Hooker. Stonewall Jackson is praying in full view and in rear of your right flank! While talking to the Great God of Battles, how could he hear what a poor cavalryman was saying. "Tell General Rodes", said he, suddenly whirling his horse towards the courier, "to move across the Old plank road; halt when he gets to the Old turnpike, and I will join him there." One more look upon the Federal lines, and then he rode rapidly down the hill, his arms flapping to the motion of his horse, over whose head it seemed, good rider as he was, he would certainly go. I expected to be told I had made a valuable personal reconnaissance—saving the lives of many soldiers, and that Jackson was indebted to me to that amount at least. Perhaps I might have been a little chagrined at Jackson's silence, and hence commented inwardly and adversely upon his horsemanship. Alas! I had looked upon him for the last time.

— Fitzhugh Lee, address to the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia, 1879

Jackson immediately returned to his corps and arranged his divisions into a line of battle to charge directly into the oblivious Federal right. The Confederates marched silently until they were merely several hundred feet from the Union position, then released a cry and full charge. Many of the Federal soldiers were captured without a shot fired, the rest were driven into a full rout. Jackson pursued back toward the center of the Federal line until dusk.[citation needed]

As Jackson and his staff were returning to camp on May 2, sentries of the 18th North Carolina Infantry Regiment mistook the group for a Union cavalry force. The sentries shouted "Halt, who goes there?", but fired before evaluating the reply; frantic shouts by Jackson's staff identifying the party were replied to by Major John D. Barry with the retort, "It's a damned Yankee trick! Fire!"[62] A second volley was fired in response. Jackson was hit by three bullets: two in the left arm and one in the right hand. Several of Jackson's men and many horses were killed in the attack. Incoming artillery rounds and darkness led to confusion, and Jackson was dropped from his stretcher while being evacuated. Surgeon Hunter McGuire amputated Jackson's left arm, and Jackson was moved to Fairfield plantation at Guinea Station. Thomas Chandler, the owner, offered the use of his home for Jackson's treatment, but Jackson suggested using Chandler's plantation office building instead.[63]

Death

[edit]

Confederate General Robert E. Lee wrote Jackson after learning of Jackson's injuries, stating: "Could I have directed events, I would have chosen for the good of the country to be disabled in your stead."[64] Jackson died of complications from pneumonia on May 10, 1863, eight days after he was shot.

Dr. McGuire wrote an account of Jackson's final hours and last words:

A few moments before he died he cried out in his delirium, 'Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks—' then stopped, leaving the sentence unfinished. Presently a smile of ineffable sweetness spread itself over his pale face, and he said quietly, and with an expression, as if of relief, 'Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.'[65]

Jackson's fatal bullet was withdrawn, examined, and found to be 67 caliber (0.67 inches, 17 mm), a type in service with the Confederate forces; Union troops in the area were using 58 caliber balls. This was one of the first instances of forensic ballistics identification derived from a firearm projectile.[66]

His body was moved to the Governor's Mansion in Richmond for the public to mourn, and he was then moved to be buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Lexington, Virginia. The arm that was amputated on May 2 was buried separately by Jackson's chaplain (Beverly Tucker Lacy), at the J. Horace Lacy house, "Ellwood", (now preserved at the Fredericksburg National Battlefield) in the Wilderness of Orange County, near the field hospital.[67]

Jackson's body was buried in "ordinary dress," but wearing a military coat. His coffin was draped with a Confederate flag and had a glass plate so that his face could be seen during public mourning. His funeral proceeded with great pomp: all pallbearers were generals (including James Longstreet), four white horses pulled the hearse, and a crowd two miles long followed the procession. In the course of public mourning, 20,000 people visited the body.[68]

Upon hearing of Jackson's death, Robert E. Lee mourned the loss of both a friend and a trusted commander. As Jackson lay dying, Lee sent a message through Chaplain Lacy, saying: "Give General Jackson my affectionate regards, and say to him: he has lost his left arm but I my right."[69] The night Lee learned of Jackson's death, he told his cook: "William, I have lost my right arm", and, "I'm bleeding at the heart."[70]

Harper's Weekly reported Jackson's death on May 23, 1863, as follows:

DEATH OF STONEWALL JACKSON.

- General "Stonewall" Jackson was badly wounded in the arm at the battles of Chancellorsville, and had his arm amputated. Jackson initially appeared to be healing, but he died from pneumonia on May 10, 1863.[71]

Personal life

[edit]Jackson's sometimes unusual command style and personality traits, combined with his frequent success in battle, contribute to his legacy as one of the greatest generals of the Civil War.[72] He was martial and stern in attitude and profoundly religious, a deacon in the Presbyterian Church. One of his many nicknames was "Old Blue Lights",[73] a term applied to a military man whose evangelical zeal burned with the intensity of the blue light used for night-time display.[74]

Physical ailments

[edit]Jackson held a lifelong belief that one of his arms was longer than the other, and thus usually held the "longer" arm up to equalize his circulation. He was described as a "champion sleeper", and occasionally even fell asleep with food in his mouth. Jackson suffered a number of ailments, for which he sought relief via contemporary practices of his day including hydrotherapy, popular in America at that time, visiting establishments at Oswego, New York (1850) and Round Hill, Massachusetts (1860) although with little evidence of success.[75][76] Jackson also suffered a significant hearing loss in both of his ears as a result of his prior service in the U.S. Army as an artillery officer.

A recurring story concerns Jackson's love of lemons, which he allegedly gnawed whole to alleviate symptoms of dyspepsia (indigestion). General Richard Taylor, son of President Zachary Taylor, wrote a passage in his war memoirs about Jackson eating lemons: "Where Jackson got his lemons 'no fellow could find out,' but he was rarely without one."[77] However, recent research by his biographer, James I. Robertson, Jr., has found that none of Jackson's contemporaries, including members of his staff, his friends, or his wife, recorded any unusual obsessions with lemons. Jackson thought of a lemon as a "rare treat ... enjoyed greatly whenever it could be obtained from the enemy's camp". Jackson was fond of all fruits, particularly peaches, "but he enjoyed with relish lemons, oranges, watermelons, apples, grapes, berries, or whatever was available".[78]

Religion

[edit]Jackson's religion has often been discussed. His biographer, Robert Lewis Dabney, suggested that "It was the fear of God which made him so fearless of all else."[79] Jackson himself had said, "My religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed."[80]

Stephen W. Sears states that "Jackson was fanatical in his Presbyterian faith, and it energized his military thought and character. Theology was the only subject he genuinely enjoyed discussing. His dispatches invariably credited an ever-kind Providence." According to Sears, "this fanatical religiosity had drawbacks. It warped Jackson's judgment of men, leading to poor appointments; it was said he preferred good Presbyterians to good soldiers."[81] James I. Robertson, Jr. suggests that Jackson was "a Christian soldier in every sense of the word". According to Robertson, Jackson "thought of the war as a religious crusade", and "viewed himself as an Old Testament warrior—like David or Joshua—who went into battle to slay the Philistines".[82]

Jackson encouraged the Confederate States Army revival that occurred in 1863,[83] although it was probably more of a grass-roots movement than a top-down revival.[84] Jackson strictly observed the Sunday Sabbath. James I. Robertson, Jr. notes that "no place existed in his Sunday schedule for labor, newspapers, or secular conversation".[85]

Command style

[edit]

In command, Jackson was extremely secretive about his plans and extremely meticulous about military discipline. This secretive nature did not stand him in good stead with his subordinates, who were often not aware of his overall operational intentions until the last minute, and who complained of being left out of key decisions.[86]

Robert E. Lee could trust Jackson with deliberately undetailed orders that conveyed Lee's overall objectives, what modern doctrine calls the "end state". This was because Jackson had a talent for understanding Lee's sometimes unstated goals, and Lee trusted Jackson with the ability to take whatever actions were necessary to implement his end state requirements. Few of Lee's subsequent corps commanders had this ability. At Gettysburg, this resulted in lost opportunities. With a defeated and disorganized Union Army trying to regroup on high ground near town and vulnerable, Lee sent one of his new corps commanders, Richard S. Ewell, discretionary orders that the heights (Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill) be taken "if practicable". Without Jackson's intuitive grasp of Lee's orders or the instinct to take advantage of sudden tactical opportunities, Ewell chose not to attempt the assault, and this failure is considered by historians to be the greatest missed opportunity of the battle.[87]

Horsemanship

[edit]Jackson had a poor reputation as a horseman. One of his soldiers, Georgia volunteer William Andrews, wrote that Jackson was "a very ordinary looking man of medium size, his uniform badly soiled as though it had seen hard service. He wore a cap pulled down nearly to his nose and was riding a rawboned horse that did not look much like a charger, unless it would be on hay or clover. He certainly made a poor figure on a horseback, with his stirrup leather six inches too short, putting his knees nearly level with his horse's back, and his heels turned out with his toes sticking behind his horse's foreshoulder. A sorry description of our most famous general, but a correct one."[88] His horse was named "Little Sorrel" (also known as "Old Sorrel"), a small chestnut gelding which was a captured Union horse from a Connecticut farm.[89][90] He rode Little Sorrel throughout the war, and was riding him when he was shot at Chancellorsville. Little Sorrel died at age 36 and is buried near a statue of Jackson on the parade grounds of VMI. (His mounted hide is on display in the VMI Museum.)[91]

Mourning his death

[edit]

After the war, Jackson's wife and young daughter Julia moved from Lexington to North Carolina. Mary Anna Jackson wrote[92] two books about her husband's life, including some of his letters. She never remarried, and was known as the "Widow of the Confederacy", living until 1915. His daughter Julia married, and bore children, but she died of typhoid fever at the age of 26 years.[93]

Legacy

[edit]Many theorists through the years have postulated that if Jackson had lived, Lee might have prevailed at Gettysburg.[94] Certainly Jackson's discipline and tactical sense were sorely missed.

As a boy, General George Patton (of World War II fame) prayed next to two portraits of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, whom he assumed were God and Jesus.[95] He once told Dwight D. Eisenhower "I will be your Jackson."[96] General Douglas MacArthur called Robert L. Eichelberger his Stonewall Jackson.[97] Chesty Puller idolized Jackson, and carried George Henderson's biography of Jackson with him on campaigns.[98] Alexander Vandegrift also idolized Jackson.

His last words, "Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees" were the inspiration for the title of Ernest Hemingway's 1950 novel Across the River and into the Trees.

Descendants

[edit]Jackson's grandson and great-grandson, both namesakes, Thomas Jonathan Jackson Christian (1888–1952) and Thomas Jonathan Jackson Christian Jr. (1915–1944), both graduated from West Point. The elder Christian was a career US Army officer who served during both World Wars and rose to the rank of brigadier general. Thomas Jonathan Jackson Christian's parents were William Edmund Christian and Julia Laura Christian. Julia was the daughter of Stonewall Jackson and his bride Mary Anna Morrison.

The younger Christian was a colonel in command of the 361st Fighter Group flying P-51 Mustangs in the European Theater of Operations in World War II when he was killed in action in August 1944; his personal aircraft, Lou IV, was one of the most photographed P-51s in the war.[99]

Commemorations

[edit]As an important element of the ideology of the "Lost Cause", Jackson has been commemorated in numerous ways, including with statues, currency, and postage.[5] A poem penned during the war soon became a popular song, "Stonewall Jackson's Way". The Stonewall Brigade Band is still active today.

West Virginia's Stonewall Jackson State Park is named in his honor. Nearby, at Stonewall Jackson's historical childhood home, his uncle's grist mill is the centerpiece of a historical site at the Jackson's Mill Center for Lifelong Learning and State 4-H Camp. The facility, located near Weston, serves as a special campus for West Virginia University and the WVU Extension Service.

During a training exercise in Virginia by U.S. Marines in 1921, the Marine commander, General Smedley Butler, was told by a local farmer that Stonewall Jackson's arm was buried nearby under a granite marker, to which Butler replied, "Bosh! I will take a squad of Marines and dig up that spot to prove you wrong!"[100] Butler found the arm in a box under the marker. He later replaced the wooden box with a metal one, and reburied the arm. He left a plaque on the granite monument marking the burial place of Jackson's arm; the plaque is no longer on the marker but can be viewed at the Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitor Center.[100][101]

Beginning in 1904 the Commonwealth of Virginia celebrated Jackson's birthday as a state holiday; the observance was eliminated, with Election Day as a replacement holiday, effective July 2020.[102][103]

Jackson is featured on the 1925 Stone Mountain Memorial half-dollar.

A Stonewall Jackson Monument was unveiled on October 11, 1919,[104] in Richmond, Virginia. It was removed on July 1, 2020, during the 2020–2021 United States racial unrest.[105][106]

-

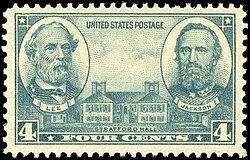

Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Stratford Hall, Army Issue of 1936

-

Portrait on the 1864 Confederate $500 banknote; Jackson was the only general featured on Confederate currency[107]

-

The 1863 sheet music The Stonewall Brigade, Dedicated to the Memory of Stonewall Jackson, the Immortal Southern Hero, and His Brave Veterans

-

Jackson on an 1863 Confederate loan

-

Davis, Lee, and Jackson on Stone Mountain

-

The Thomas Jonathan Jackson sculpture in downtown Charlottesville, Virginia

-

Statue of Jackson in downtown Clarksburg, West Virginia

-

Bust of Jackson at the Washington-Wilkes Historical Museum

-

The Stonewall Jackson Monument in Richmond, Virginia being removed in 2020

-

Jackson reading the Bible in a Confederate camp in a stained glass window of the Washington National Cathedral. The windows were removed in 2017.[108]

See also

[edit]- William B. Ebbert, 1st Lt., W. Virginia Infantry, Union Army. (1923 quote recalling battle of Winchester, March 1862)

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- Stonewall Jackson's Headquarters Museum

- List of memorials to Stonewall Jackson

- Stonewall Jackson's arm

- Removal of Confederate monuments and memorials

- Stonewall Brigade

Notes

[edit]- ^ Eicher, High Commands, p. 316; Robertson, p. 7. The physician, Dr. James McCally, recalls delivering baby Thomas on January 20, 1809, just before midnight, but the family has insisted since then that he was born in the first minutes of January 21. The later date is the one generally acknowledged in biographies.

- ^ James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend (1997).

- ^ Hamner, Christopher. "The Possible Path of Barnard Bee." Teachinghistory.org. Accessed July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson Timeline". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Wallace Hettle, Inventing Stonewall Jackson: A Civil War Hero in History and Memory (Louisiana State University Press, 2011)

- ^ Farwell, p. xi, states that the overwhelmingly common usage of the middle name Jonathan was never documented and that Jackson did not acknowledge it; he instead used the signature form "T. J. Jackson." Robertson, p. 19, states that a county document on February 28, 1841, was the first recorded instance of Jackson's using a middle initial, although "whether it stood for his father Jonathan's name is not known." All of the other references to this article cite his full name as Thomas Jonathan Jackson.

- ^ Robertson, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Robertson, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Edward's second son was David Edward Jackson. Talbot, Vivian Linford (1996). David E. Jackson: Field Captain of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade. Jackson Hole: Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. p. 17.

- ^ VMI Jackson genealogy site; Robertson, p. 4.

- ^ Talbot, op. cit., p. 18

- ^ "Jackson Family Genealogy". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "Was Stonewall Jackson born in Parkersburg? – NewsandSentinel.com | News, Sports, Jobs, Community Information – Parkersburg News and Sentinel". NewsandSentinel.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Robertson, p. 7.

- ^ Robertson, p. 8.

- ^ Robertson, p. 10.

- ^ Robertson, pp. 9–16. Robertson refers to multiple bachelor uncles in residence at the mill, but does not name them.

- ^ Robertson, p. 17.

- ^ "Laura Jackson Arnold: Sister of General Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackon". Civil War Women Blog. November 29, 2010. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ a b George Cullum. "Register of Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy Class of 1846". Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ Henderson, George Francis Robert (1898). Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War (1st ed.). Longmans, Green and Company. p. 69.

- ^ Robertson, p. 69.

- ^ Eiedson, George T. (June 13, 1993). "Before He Was 'Stonewall,' Jackson Served in Florida". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ Gwynne, S. C. Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson. New York: Scribner, 2014, pp. 110–18.

- ^ Robertson, pp. 108–10. He left the Army on March 21, 1851, but stayed on the rolls, officially on furlough, for nine months. His resignation took effect formally on February 2, 1852, and he joined the VMI faculty in August 1851.

- ^ Eggleston, George Cary (1875). A Rebel's Recollections. Putnam. p. 152.

- ^ Vandiver, Frank E. (1989). Mighty Stonewall. Texas A&M University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780890963913.

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson – Frequently Asked Questions – VMI Archives". Virginia Military Institute Archives. 2001. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Clint (2002). In the Footsteps of Stonewall Jackson. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair. p. 122. ISBN 0-89587-244-7.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1910). The Encyclopaedia Britannica : a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information. Internet Archive. New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 110.

- ^ Graham, Chris (October 12, 2017). "Myths & Misunderstandings: Stonewall Jackson's Sunday School". American Civil War Museum. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

- ^ Jackson, Mary Anna, 1895, p. 78

- ^ Robertson, p. 169.

- ^ Knadler, Jessie (May 15, 2018). "New Research Sheds Light On Slaves Owned By Stonewall Jackson". www.wvtf.org. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Spurgeon, pp. 4-5

- ^ Spurgeon, pp. 5-8

- ^ Robertson, pp. 191–92.

- ^ Palmer, Brian; Wessler, Seth Freed (December 2018). "The Costs of the Confederacy". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Hettle, Wallace. Inventing Stonewall Jackson. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8071-3781-9.

- ^ Jackson, p. 152

- ^ Hettle, p. 85.

- ^ Robertson, p. 191.

- ^ Spurgeon, Larry (2018). "Stonewall Jackson's Slaves" (PDF). Rockbridge History. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

- ^ Hettle, pp. 83-85.

- ^ Hettle, p. 72

- ^ Spurgeon, pp. 18-20

- ^ Rossino, Alexander (2021). Their Maryland: The Army of Northern Virginia From the Potomac Crossing to Sharpsburg in September 1862. Savas Beatle. p. 274-277. ISBN 9781611215588.

- ^ Isbell, Sherman. "Archibald Alexander Travelogue". Archived from the original on September 14, 2005. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ Robertson, p. 157.

- ^ Snell, Mark A., West Virginia and the Civil War, History Press, 2011, pg.45

- ^ a b Eicher, High Commands, p. 316.

- ^ Freeman, Lee's Lieutenants, vol. 1, p. 82; Robertson, p. 264. McPherson, p. 342, reports the quotation after "stone wall" as being "Rally around the Virginians!"

- ^ See, for instance, Goldfield, David, et al., The American Journey: A History of the United States, Prentice Hall, 1999, ISBN 0-13-088243-7. There are additional controversies about what Bee said and whether he said anything at all. See Freeman, Lee's Lieutenants, vol. 1, pp. 733–34.

- ^ McPherson, p. 342.

- ^ Robertson, pp. 263, 268.

- ^ See, for instance, Freeman, R.E. Lee, vol. 2, p. 247.

- ^ Henderson, George Francis Robert (1903). Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War. Vol. II. New York: Longmans, Green. p. 17. OCLC 793450187.

- ^ Wert, p. 206.

- ^ "Origin of the Movement Around Pope's Army of Virginia, August 1862 by Michael Collie. Retrieved September 27, 2017 [1] and Archie P. McDonald, ed., Make Me a Map of the Valley: the Civil War Journal of Jackson's Topographer, (Dallas 1973) pp. 117–18; and James I. Robertson, Jr., Stonewall Jackson: the Man, the Soldier, and the Legend, (New York 1997) p. 547, n130 p. 887

- ^ Robertson, p. 645.

- ^ Robertson, p. 630.

- ^ Foote, Shelby, The Civil War: A Narrative, Vol. 2

- ^ Apperson, p. 430.

- ^ Robertson, p. 739

- ^ McGuire, pp. 162–63.

- ^ Grieve, Taylor Nicole (2013). Objective Analysis of Toolmarks in Forensics (MS thesis thesis). Iowa State University. p. 6. hdl:20.500.12876/27203. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019.

- ^ Sorensen, James. "Stonewall Jackson's Arm Archived January 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine" American Heritage, April/May 2005.

- ^ jackson, mary (1895). "Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson by his widow, Mary Anna Jackson".

- ^ Robertson, p. 746.

- ^ Hall, Kenneth (2005). Stonewall Jackson and religious faith in military command. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786420858.

- ^ "Death of Stonewall Jackson", Harpers Weekly, May 23, 1863

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson: Popular Questions". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson's Way". Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- ^ Gareth Atkins, review of Evangelicals in the Royal Navy, 1775–1815: Blue Lights and Psalm-Singers by Richard Blake (review no. 799). Retrieved December 24, 2011, at www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/799

- ^ Cartmell, Donald (2001). "The Legend of Stonewall". The Civil War Book of Lists. Franklin Lakes, New Jersey: The Career Press Inc. pp. 187–92. ISBN 1-56414-504-2.

- ^ Samaritan Medical Center (September 2008). "Stonewall Jackson and the Henderson Hydropath". in Samaritan Medical Center Newsletter (PDF). Vol. 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- ^ Taylor, p. 50

- ^ Robertson, p. xi.

- ^ Dabney, Robert L. "True Courage: A Memorial Sermon for General Thomas J. "Stone-wall Jackson" (PDF). Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Selby, John Millin (2000). Stonewall Jackson As Military Commander. p. 25.

- ^ Sears, Stephen W. (March 16, 1997). "Onward, Christian Soldier". The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ White, Davin (October 15, 2010). "Stonewall Jackson biographer says religion drove Civil War general". The Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Duewel, Wesley L. (2010). Revival Fire. Zondervan. p. 128. ISBN 978-0310877097.

- ^ Summers, Mark. "The Great Harvest: Revival in the Confederate Army during the Civil War". Religion & Liberty. 21 (3). Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Robertson, James I. "Stonewall Jackson: Christian Soldier" (PDF). Virginia Center for Civil War Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Robertson, p. xiv.

- ^ Pfanz, p. 344; Eicher, Longest Night, p. 517; Sears, p. 228; Trudeau, p. 253. Both Sears and Trudeau record "if possible".

- ^ Robertson, p. 499.

- ^ Robertson, p. 230.

- ^ "Little Sorrel, Connecticut's Confederate War Horse". ConnecticutHistory.org. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Little Sorrel Buried at VMI July 20, 1997" Archived October 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; Robertson, p. 922, n. 16.

- ^ Jackson, Mary Anna, Jackson Memoirs, 1895

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson FAQ – Virginia Military Institute Archives". www.vmi.edu. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ See, for instance, Sears, Gettysburg, pp. 233–34. Alternative theories about Gettysburg are prominent ideas in the literature about the Lost Cause.

- ^ Robert H. Patton, The Pattons: A Personal History of an American Family (New York: Crown Publishers, 1994), 90.

- ^ Matthew F. Holland (2001). Eisenhower Between the Wars: The Making of a General and Statesman. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-275-96340-8.

- ^ Major Matthew H. Fath (2015). Eichelberger – Intrepidity, Iron Will, And Intellect: General Robert L. Eichelberger And Military Genius. Verdun Press. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-1-78625-238-8.

- ^ Major Mickey L. Quintrall USAF (2015). The Chesty Puller Paragon: Leadership Dogma Or Model Doctrine?. Lucknow Books. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-78625-075-9.

- ^ "Thomas Jonathan Christian Jackson Christian Jr: American Air Museum in Britain".

- ^ a b Farwell, 1993, p. 513

- ^ Horwitz, 1999, p. 232

- ^ Vozzella, Laura (January 21, 2020). "Virginia Senate votes to eliminate Lee-Jackson Day, create new Election Day holiday". Washington Post. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Virginia General Assembly SB 601 Legal holidays; Election Day

- ^ "General Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson Equestrian, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Times-Dispatch, MARK ROBINSON Richmond (July 2020). "UPDATE: Crews on scene preparing for removal of Jackson statue on Monument Avenue". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Stonewall Jackson removed from Richmond's Monument Avenue". AP NEWS. July 1, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ Levin, Kevin M. (April 21, 2016). "When Dixie Put Slaves on the Money". The Daily Beast. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Boorstein, Michelle (September 6, 2017). "Washington National Cathedral to remove stained glass windows honoring Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson". The Washington Post.

References

[edit]- Alexander, Bevin. Lost Victories: The Military Genius of Stonewall Jackson. New York: Holt, 1992, ISBN 978-0-8050-1830-1.

- Apperson, John Samuel. Repairing the "March of Mars": The Civil War diaries of John Samuel Apperson, hospital steward in the Stonewall Brigade, 1861–1865. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-86554-779-3.

- Bryson, Bill. A Walk in the Woods. New York: Broadway Books, 1998. ISBN 0-7679-0251-3.

- Cleary, Ben. Searching for Stonewall Jackson: A Quest for Legacy in a Divided America, 2019. Description and arrow-searchable & scrollable preview. Reviews at Kirkus & Publishers Weekly. Grand Central Publishing.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 978-0-684-84944-7.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Farwell, Byron. Stonewall: A Biography of General Thomas J. Jackson. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1993. ISBN 978-0-393-31086-3.

- Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1946. ISBN 978-0-684-85979-8.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934–35. ISBN 978-0-684-15485-5.

- Henderson, G. F. R. Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War. New York: Smithmark, 1995. ISBN 0-8317-3288-1. First published in 1898 by Longman, Greens, and Co. (The 1900 version has an introduction by Field Marshal Viscount Wolseley.)

- Hettle, Wallace. Inventing Stonewall Jackson: A Civil War Hero in History and Memory (Louisiana State University Press, 2011)

- Jackson, Mary Anna (1895). Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson. Louisville, Ky. : Prentice Press, Courier-Journal job Print. Co.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence C. Buel, eds. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Archived December 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. 4 vols. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. OCLC 2048818.

- McGuire, Hunter. "Death of Stonewall Jackson". Southern Historical Society Papers 14 (1886).

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The First Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8078-2624-9.

- Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-02-864685-1.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 978-0-395-86761-7.

- Sharlet, Jeff. "Through a Glass, Darkly: How the Christian Right is Reimagining U.S. History." Harpers, December 2006.

- Taylor, Richard. Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War. Nashville, Tennessee: J.S. Sanders & Co., 2001. ISBN 1-879941-21-X. First published 1879 by D. Appleton.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 978-0-06-019363-8.

- Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 978-0-671-70921-1.

- Jackson genealogy site at Virginia Military Institute

Further reading

[edit]- Austin, Aurelia (1967). Georgia boys with "Stonewall" Jackson: James Thomas Thompson and the Walton Infantry. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0820335230. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Chambers, Lenoir. Stonewall Jackson. New York: Morrow, 1959. OCLC 186539122.

- Cooke, John Esten; Hoge, Moses Drury; Jones, John William (1876). Stonewall Jackson: A Military Biography. New York: D. Appleton and Company. OCLC 299589.

- Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Dabney, R. L. Life of Lieut.-Gen. Thomas J. Jackson (Stonewall Jackson). London: James Nisbet and Co., 1866. OCLC 457442354.

- Douglas, Henry Kyd. I Rode with Stonewall: The War Experiences of the Youngest Member of Jackson's Staff. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940. ISBN 0-8078-0337-5.

- Gwynne, S. C. Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4516-7328-9.

- King, Benjamin. A Bullet for Stonewall, Pelican Publishing Company, 1990,. ISBN 0882897683.

- Lively, Mathew W. Calamity at Chancellorsville: The Wounding and Death of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61121-138-2.

- Mackowski, Chris, and Kristopher D. White. The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson: The Mortal Wounding of the Confederacy's Greatest Icon. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61121-150-4.

- Randolph, Sarah N. (1876). The Life of General Thomas J. Jackson. Lippincott & Co.

- Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson's Book of Maxims. Nashville, Tennessee: Cumberland House, 2002. ISBN 1-58182-296-0.

- Shackel, Paul A. Archaeology and Created Memory: Public History in a National Park. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-0-306-46177-4.

- White, Henry A. Stonewall Jackson. Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs and Co., 1909. OCLC 3911913.

- Wilkins, J. Steven. All Things for Good: The Steadfast Fidelity of Stonewall Jackson. Nashville, Tennessee: Cumberland House Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-58182-225-1.

External links

[edit]- Virginia Military Institute Archives Stonewall Jackson Resources

- before-death-on-maryland Stonewall Jackson Original Letter as Lieutenant General, Near Fredericksburg, 1863 Archived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Jackson genealogy site

- "Death of 'Stonewall' Jackson" Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Southern Confederacy, May 12, 1863. Atlanta Historic Newspapers Archive. Digital Library of Georgia.

- Fitzhugh Lee's 1879 address on Chancellorsville

- The Stonewall Jackson House

- Animated history of the campaigns of Stonewall Jackson Archived December 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Details on John Jackson's larceny trial in the Court Records of the Old Bailey

- Stonewall Jackson's Headquarters, Winchester, VA

- Guinea Station, the place where Thomas Jackson died

Stonewall Jackson

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Family Background

Ancestry and Childhood Hardships

Thomas Jonathan Jackson descended from Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who emigrated from Ulster to the American colonies in the early 18th century. His great-grandfather John Jackson settled on the Virginia frontier after arriving from Ireland around 1732, establishing a lineage of farmers and attorneys in the region.[7][8] Jackson was born on January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), the third child of attorney Jonathan Jackson (1790–1826) and Julia Beckwith Neale (1798–1831). His siblings included older brother Jonathan Warren Jackson (1821–1841) and younger sister Laura Ann Jackson (born March 27, 1826).[9][10][11] Jackson's father died on March 26, 1826, at age 36, likely from typhoid fever contracted while nursing a family member, leaving the family in financial distress due to Jonathan's failed investments and legal practice struggles. Thomas, then two years old, faced immediate poverty as his widowed mother relocated the children to a smaller home and attempted to sustain them through sewing and tutoring. Julia remarried Blake Baker Woodson, a widowed farmer nearly 30 years her senior, on November 4, 1830, but the union exacerbated tensions, as Woodson showed reluctance to support her children amid ongoing economic hardship.[12][10][13] Julia died on December 3, 1831, at age 33, possibly from complications related to illness or recent childbirth, orphaning seven-year-old Thomas and his siblings. Woodson, unwilling or unable to care for the children, arranged for their separation: Thomas and Laura were sent to paternal relatives, while Warren went to maternal kin. Thomas, aged seven, was placed with his half-uncle Cummins Edward Jackson (1802–1849), who operated a gristmill and farm at Jackson's Mill in present-day Lewis County, West Virginia. Cummins provided basic shelter but enforced strict discipline, requiring Thomas to perform demanding manual labor including farm work, sheep herding with the aid of a dog, and mill operations.[1][9][14] These years instilled resilience amid persistent hardships: familial instability, with separation from siblings (Warren died of tuberculosis in 1841); economic privation that limited access to formal schooling until age 13; and physical toil that built endurance but hindered early intellectual development. Largely self-taught through borrowed books and sporadic attendance at local schools taught by Cummins, young Jackson exhibited determination, compensating for educational deficits through rigorous self-discipline that foreshadowed his later military precision.[10][5][15]Education and Formative Experiences

Thomas Jonathan Jackson experienced significant family loss in his early childhood, with his father dying in 1826 when Jackson was two years old and his mother passing away in 1830 when he was six.[10] Following these tragedies, he and his siblings were raised by their uncle, Cummins E. Jackson, at Jackson's Mill near Weston in what was then Virginia.[16] There, Jackson performed demanding physical labor, including hauling heavy grain sacks up a steep hill to the mill, driving oxen teams, and herding sheep, which contributed to his robust physique and enduring stamina.[17][18] Jackson's formal education was limited and intermittent, as farm and mill duties took precedence over schooling; he did not begin attending local classes until around age thirteen and progressed slowly due to frequent absences.[1] To supplement this, he pursued self-directed study, learning to read and committing subjects to memory through intense concentration, often reading by the light of burning pine knots late into the night.[19][20] Despite his rudimentary background, by his late teens, Jackson secured a position teaching at a neighborhood school near Jackson's Mill around 1841, relying on earnest effort and borrowed textbooks to instruct pupils in basic subjects.[21][16] These formative years of hardship, manual toil, and determined self-improvement cultivated Jackson's renowned discipline, resilience, and methodical approach to learning, traits that later distinguished his academic performance at West Point and military leadership.[10][5] He also began teaching literacy to enslaved individuals during this period, reflecting an early commitment to education amid his constrained circumstances.[17]Military Education and Pre-Civil War Service

West Point and Mexican-American War

Thomas Jonathan Jackson entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in July 1842, securing an appointment as a congressional nominee after the death of the original selectee from his district. Lacking prior formal education beyond basic schooling, he initially struggled with the curriculum, relying on rote memorization of textbooks and persistent questioning of instructors despite accumulating demerits for disciplinary issues. Through determination and self-study, he improved markedly, graduating 17th in general merit out of a class of 59 on July 1, 1846—just as the Mexican-American War commenced.[22][23][10] Commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment upon graduation, Jackson was promptly assigned to General Winfield Scott's army for the invasion of Mexico. He participated in the advance from Veracruz to Mexico City, serving as an artillery officer in engagements such as Cerro Gordo, Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec. His performance under fire drew commendations for bravery and tactical acumen; at Contreras and Churubusco on August 19–20, 1847, Jackson refused orders to retreat his exposed battery, holding position until reinforced, which contributed to Union victories and earned him brevets to first lieutenant and captain. For overall gallantry in the campaign, he received a brevet promotion to major by the war's end in 1848.[23][10][16]Service in the U.S. Army and Early Recognition

Following the Mexican-American War, Thomas J. Jackson served in routine garrison duties with the 1st U.S. Artillery. Initially assigned to posts in Florida, including isolated Fort Meade east of Tampa, he encountered tensions with his commanding officer, Major William H. French, over matters of discipline and authority. From 1849 to 1851, Jackson was stationed at Fort Hamilton in New York Harbor, where he acted as quartermaster and provided instruction in artillery tactics to fellow officers and recruits.[24][25] Jackson's early military recognition stemmed primarily from his conduct during the Mexican-American War, where he demonstrated exceptional bravery under fire. At the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco on August 19–20, 1847, he commanded a section of artillery with cool determination, earning a brevet promotion to first lieutenant on August 20, 1847. During the storming of Chapultepec on September 13, 1847, Jackson positioned two cannons on an exposed causeway and maintained fire against intense Mexican resistance, supporting the infantry assault and receiving a brevet promotion to captain for his gallantry.[16][26] These battlefield brevets highlighted Jackson's competence as an artillery officer, though his peacetime service offered little further advancement or excitement, leading him to view regular army life as stagnant. Holding the regular rank of first lieutenant with brevet captain status, Jackson resigned his U.S. Army commission in early 1851, seeking greater purpose and stability in civilian instruction.[23][27]Civilian Career at VMI

Professorship and Teaching Methods