Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

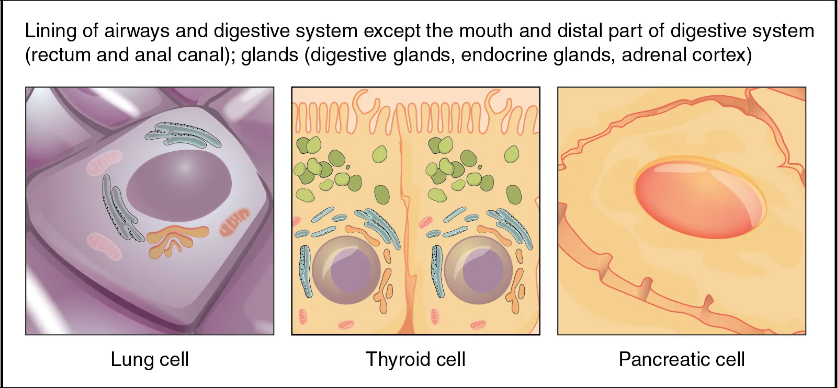

Endoderm

View on Wikipedia| Endoderm | |

|---|---|

Tissues derived from endoderm. | |

| Details | |

| Days | 16 |

| Precursor | Epiblast |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D004707 |

| FMA | 69071 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Endoderm is the innermost of the three primary germ layers in the very early embryo. The other two layers are the ectoderm (outside layer) and mesoderm (middle layer).[1] Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastrula, which develops into the endoderm.[2]

The endoderm consists at first of flattened cells, which subsequently become columnar. It forms the epithelial lining of multiple systems.

In plant biology, endoderm corresponds to the innermost part of the cortex (bark) in young shoots and young roots often consisting of a single cell layer. As the plant becomes older, more endoderm will lignify.

Production

[edit]The following chart shows the tissues produced by the endoderm. The embryonic endoderm develops into the interior linings of two tubes in the body, the digestive and respiratory tube.[3]

| Layer | Category | System | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General[4] | Gastrointestinal tract | the entire alimentary canal except part of the mouth, pharynx and the terminal part of the rectum (which are lined by involutions of the ectoderm), the lining cells of all the glands which open into the digestive tube, including those of the liver and pancreas | |

| General | Respiratory tract | the trachea, bronchi, and alveoli of the lungs | |

| General | Endocrine glands and organs | the lining of the follicles of the thyroid gland and the epithelial component of the thymus (i.e. thymic epithelial cells). | |

| Auditory system | the epithelium of the auditory tube and tympanic cavity | ||

| Urinary system | the urinary bladder and part of the urethra |

Liver and pancreas cells are believed to derive from a common precursor.[5]

In humans, the endoderm can differentiate into distinguishable organs after 5 weeks of embryonic development.

Additional images

[edit]-

Section through the embryo.

-

Section through ovum imbedded in the uterine decidua

-

Signaling pathway to inducing endoderm

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 49 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 49 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Langman's Medical Embryology, 11th edition. 2010.

- ^ Fukuda, Kimiko; Kikuchi, Yutaka (August 2005). "Endoderm development in vertebrates: fate mapping, induction and regional specification". Development, Growth and Differentiation. 47 (6): 343–355. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169X.2005.00815.x. ISSN 0012-1592. PMID 16109032. S2CID 26241717. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Gilbert, SF. "Endoderm". Sinauer Associates. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ The General category denotes that all or most of the animals containing this layer produce the adjacent product.

- ^ Zaret KS (October 2001). "Hepatocyte differentiation: from the endoderm and beyond". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11 (5): 568–74. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00234-3. PMID 11532400.