Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neurulation

View on Wikipedia| Neurulation | |

|---|---|

Transverse sections that show the progression of the neural plate to the neural groove from bottom to top | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D054261 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Neurulation refers to the folding process in vertebrate embryos, which includes the transformation of the neural plate into the neural tube.[1] The embryo at this stage is termed the neurula.

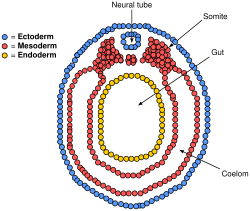

The process begins when the notochord induces the formation of the central nervous system (CNS) by signaling the ectoderm germ layer above it to form the thick and flat neural plate. The neural plate folds in upon itself to form the neural tube, which will later differentiate into the spinal cord and the brain, eventually forming the central nervous system.[2] Computer simulations found that cell wedging and differential proliferation are sufficient for mammalian neurulation.[3]

Different portions of the neural tube form by two different processes, called primary and secondary neurulation, in different species.[4]

- In primary neurulation, the neural plate creases inward until the edges come in contact and fuse.

- In secondary neurulation, the tube forms by hollowing out of the interior of a solid precursor.

Primary neurulation

[edit]

Primary neural induction

[edit]The concept of induction originated in work by Pandor in 1817.[5] The first experiments proving induction were attributed by Viktor Hamburger[6] to independent discoveries of both Hans Spemann of Germany in 1901[7] and Warren Lewis of the USA in 1904.[8] It was Hans Spemann who first popularized the term "primary neural induction" in reference to the first differentiation of ectoderm into neural tissue during neurulation.[9][10] It was called "primary" because it was thought to be the first induction event in embryogenesis. The Nobel prize-winning experiment was done by his student Hilda Mangold.[9] Ectoderm from the region of the dorsal lip of the blastopore of a developing salamander embryo was transplanted into another embryo and this "organizer" tissue "induced" the formation of a full secondary axis changing surrounding tissue in the original embryo from ectodermal to neural tissue. The tissue from the donor embryo was therefore referred to as the inducer because it induced the change.[9] While the organizer is the dorsal lip of the blastopore, this is not one set of cells, but rather is a constantly changing group of cells that migrate over the dorsal lip of the blastopore by forming apically constricted bottle cells. At any given time during gastrulation there will be different cells that make up the organizer.[11]

Subsequent work on inducers by scientists over the 20th century demonstrated that not only could the dorsal lip of the blastopore act as an inducer but so could a huge number of other seemingly unrelated items. This began when boiled ectoderm was found to still be able to induce by Johannes Holtfreter.[12] Items as diverse as low pH, cyclic AMP, even floor dust could act as inducers leading to considerable consternation.[13] Even tissue which could not induce when living could induce when boiled.[14] Other items such as lard, wax, banana peels and coagulated frog's blood did not induce.[15] The hunt for a chemically based inducer molecule was taken up by developmental molecular biologists and a vast literature of items shown to have inducer abilities continued to grow.[16][17]

More recently, the inducer molecule has been attributed to genes, and in 1995, there was a call for all the genes involved in primary neural induction and all their interactions to be catalogued, in an effort to determine "the molecular nature of Spemann's organizer".[18] Several other proteins and growth factors have also been invoked as inducers, including soluble growth factors such as bone morphogenetic protein and a requirement for "inhibitory signals" such as noggin and follistatin.

Even before the term induction was popularized, several authors, beginning with Hans Driesch in 1894,[19] suggested that primary neural induction might be mechanical in nature. A mechanochemical-based model for primary neural induction was proposed in 1985 by G.W. Brodland and R. Gordon.[20] An actual physical wave of contraction has been shown to originate from the precise location of the Spemann organizer which then traverses the presumptive neural epithelium[21] and a full working model of how primary neural inductions was proposed in 2006.[22][23] There has long been a general reluctance in the field to consider the possibility that primary neural induction might be initiated by mechanical effects.[24] A full explanation for primary neural induction remains yet to be found.

Shape change

[edit]As neurulation proceeds after induction, the cells of the neural plate become high-columnar and can be identified through microscopy as different from the surrounding presumptive epithelial ectoderm (epiblastic endoderm in amniotes). The cells move laterally and away from the central axis and change into a truncated pyramid shape. This pyramid shape is achieved through tubulin and actin in the apical portion of the cell which constricts as they move. The variation in cell shapes is partially determined by the location of the nucleus within the cell, causing bulging in areas of the cells forcing the height and shape of the cell to change. This process is known as apical constriction.[25][26] The result is a flattening of the differentiating neural plate which is particularly obvious in salamanders when the previously round gastrula becomes a rounded ball with a flat top.[27] See Neural plate.

Folding

[edit]The process of the flat neural plate folding into the cylindrical neural tube is termed primary neurulation. As a result of the cellular shape changes, the neural plate forms the medial hinge point (MHP). The expanding epidermis puts pressure on the MHP and causes the neural plate to fold resulting in neural folds and the creation of the neural groove. The neural folds form dorsolateral hinge points (DLHP) and pressure on this hinge cause the neural folds to meet and fuse at the midline. The fusion requires the regulation of cell adhesion molecules. The neural plate switches from E-cadherin expression to N-cadherin and N-CAM expression to recognize each other as the same tissue and close the tube. This change in expression stops the binding of the neural tube to the epidermis.

The notochord plays an integral role in the development of the neural tube. Prior to neurulation, during the migration of epiblastic endoderm cells towards the hypoblastic endoderm, the notochordal process opens into an arch termed the notochordal plate and attaches overlying neuroepithelium of the neural plate. The notochordal plate then serves as an anchor for the neural plate and pushes the two edges of the plate upwards while keeping the middle section anchored. Some of the notochodral cells become incorporated into the center section neural plate to later form the floor plate of the neural tube. The notochord plate separates and forms the solid notochord.[4]

The folding of the neural tube to form an actual tube does not occur all at once. Instead, it begins approximately at the level of the fourth somite at Carnegie stage 9 (around embryonic day 20 in humans). The lateral edges of the neural plate touch in the midline and join together. This continues both cranially (toward the head) and caudally (toward the tail). The openings that are formed at the cranial and caudal regions are termed the cranial and caudal neuropores. In human embryos, the cranial neuropore closes approximately on day 24 and the caudal neuropore on day 28.[28] Failure of the cranial (superior) and caudal (inferior) neuropore closure results in conditions called anencephaly and spina bifida, respectively. Additionally, failure of the neural tube to close throughout the length of the body results in a condition called rachischisis.[29]

Patterning

[edit]

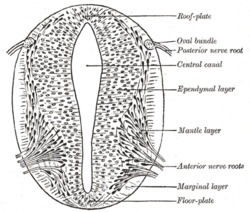

According to the French Flag model where stages of development are directed by gene product gradients, several genes are considered important for inducing patterns in the open neural plate, especially for the development of neurogenic placodes. These placodes first become evident histologically in the open neural plate. After sonic hedgehog (SHH) signalling from the notochord induces its formation, the floor plate of the incipient neural tube also secretes SHH. After closure, the neural tube forms a basal or floor plate and a roof or alar plate in response to the combined effects of SHH and factors including BMP4 secreted by the roof plate. The basal plate forms most of the ventral portion of the nervous system, including the motor portion of the spinal cord and brain stem; the alar plate forms the dorsal portions, devoted mostly to sensory processing.[30]

The dorsal epidermis expresses BMP4 and BMP7. The roof plate of the neural tube responds to those signals by expressing more BMP4 and other transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signals to form a dorsal/ventral gradient among the neural tube. The notochord expresses SHH. The floor plate responds to SHH by producing its own SHH and forming a gradient. These gradients allow for the differential expression of transcription factors.[30]

Complexities of the model

[edit]Neural tube closure is not entirely understood. Closure of the neural tube varies by species. In mammals, closure occurs by meeting at multiple points which then close up and down. In birds, neural tube closure begins at one point of the midbrain and moves anteriorly and posteriorly.[31][32]

Secondary neurulation

[edit]Primary neurulation develops into secondary neurulation when the caudal neuropore undergoes final closure. The cavity of the spinal cord extends into the neural cord.[33] In secondary neurulation, the neural ectoderm and some cells from the endoderm form the medullary cord. The medullary cord condenses, separates and then forms cavities.[34] These cavities then merge to form a single tube. Secondary neurulation occurs in the posterior section of most animals but it is better expressed in birds. Tubes from both primary and secondary neurulation eventually connect at around the sixth week of development.[35]

In humans, the mechanisms of secondary neurulation plays an important role given its impact on the proper formation of the human posterior spinal cord. Errors at any point in the process can yield problems. For example, retained medullary cord occurs due to a partial or complete arrest of secondary neurulation that creates a non-functional portion on the vestigial end.[36]

Early brain development

[edit]The anterior portion of the neural tube forms the three main parts of the brain: the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and the hindbrain (rhombencephalon).[37] These structures initially appear just after neural tube closure as bulges called brain vesicles in a pattern specified by anterior-posterior patterning genes, including Hox genes, other transcription factors such as Emx, Otx, and Pax genes, and secreted signaling factors such as fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and Wnts.[38] These brain vesicles further divide into subregions. The prosencephalon gives rise to the telencephalon and diencephalon, and the rhombencephalon generates the metencephalon and myelencephalon. The hindbrain, which is the evolutionarily most ancient part of the chordate brain, also divides into different segments called rhombomeres. The rhombomeres generate many of the most essential neural circuits needed for life, including those that control respiration and heart rate, and produce most of the cranial nerves.[37] Neural crest cells form ganglia above each rhombomere. The early neural tube is primarily composed of the germinal neuroepithelium, later called the ventricular zone, which contains primary neural stem cells called radial glial cells and serves as the main source of neurons produced during brain development through the process of neurogenesis.[39][40]

Non-neural ectoderm tissue

[edit]Paraxial mesoderm surrounding the notochord at the sides will develop into the somites (future muscles, bones, and contributes to the formation of limbs of the vertebrate ).[41]

Neural crest cells

[edit]Masses of tissue called the neural crest that are located at the very edges of the lateral plates of the folding neural tube separate from the neural tube and migrate to become a variety of different but important cells.[citation needed]

Neural crest cells will migrate through the embryo and will give rise to several cell populations, including pigment cells and the cells of the peripheral nervous system.[citation needed]

Neural tube defects

[edit]Failure of neurulation, especially failure of closure of the neural tube are among the most common and disabling birth defects in humans, occurring in roughly 1 in every 500 live births.[42] Failure of the rostral end of the neural tube to close results in anencephaly, or lack of brain development, and is most often fatal.[43] Failure of the caudal end of the neural tube to close causes a condition known as spina bifida, in which the spinal cord fails to close.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Larsen WJ. Human Embryology. Third ed. 2001.P 86. ISBN 0-443-06583-7

- ^ "Chapter 14. Gastrulation and Neurulation". biology.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Nielsen, Bjarke Frost; Nissen, Silas Boye; Sneppen, Kim; Mathiesen, Joachim; Trusina, Ala (February 21, 2020). "Model to Link Cell Shape and Polarity with Organogenesis". iScience. 23 (2) 100830. Bibcode:2020iSci...23j0830N. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.100830. PMC 6994644. PMID 31986479.

- ^ a b Wolpert, Lewis; Tickle, Cheryll; Arias, Alfonso Martinez (2015). Principles of development (Fifth ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-19-870988-6.

- ^ Tiedemann, H. Chemical approach to the inducing agents. In: O. Nakamura & S. Toivonen (eds.), Organizer - A Milestone of a Half- Century from Spemann, Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland Biomedical Press, p. 91- 117. 1978

- ^ Hamburger, V.. The Heritage of Experimental Embryology: Hans Spemann and the Organizer. New York: Oxford University Press. 1988

- ^ Spemann, H. Über Korrelationen in der Entwicklung des Auges/On correlations in the development of the eye. Verh. anat. Ges. Jena 15, 61-79. 1901

- ^ Lewis, WH Experimental studies on the development of the eye in amphibia. I. On the origin of the lens in Rana palustris. Amer. J. Anat. 3, 505-536. 1904

- ^ a b c Spemann, H. & H. Mangold, Über Induktion von Embryonalanlagen durch Implantation artfremder Organisatoren/On induction of embryo anlagen by implantation of organizers of other species. Archiv mikroskop. Anat. Entwicklungsmech. 100, 599-638 1924

- ^ Spemann, H. & H. Mangold 1924: Induction of embryonic primordia by implantation of organizers from a different species. In: B.H. Willier & J.M. Oppenheimer (eds.), Foundations of Experimental Embryology, (translated 1964 ed.), Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, p. 144-184

- ^ Gordon, R., N. K. Björklund & P. D. Nieuwkoop. Dialogue on embryonic induction and differentiation waves. Int. Rev. Cytol. 150, 373-420. 1994

- ^ Holtfreter, J. Eigenschaften und Verbreitung induzierender Stoffe/Characteristics and spreading of inducing substances. Naturwissenschaften 21, 766-770. 1933

- ^ Twitty, VC, Of Scientists and Salamanders Freeman, San Francisco, CA.1966

- ^ Spemann, H., F.G. Fischer & E. Wehmeier Fortgesetzte Versuche zur Analyse der Induktionsmittel in der Embryonalentwicklung/Continued attempts at analysis of the cause of induction means in embryonic development. Natuwissenschaften 21, 505-506. 1933

- ^ Weiss, P.A.. The so-called organizer and the problem of organization in amphibian development. Physiol. Rev. 15(4), 639-674. 1935

- ^ De Robertis, E.M., M. Blum, C. Niehrs & H. Steinbeisser, goosecoid and the organizer. Development (Suppl.), 167-171. 1992

- ^ Hahn, M. & H. Jäckle Drosophila goosecoid participates in neural development but not in body axis formation. EMBO J. 15(12), 3077-3084. 1996

- ^ De Robertis, E.M. Dismantling the organizer. Nature 374(6521), 407-408. 1995

- ^ Driesch, HAE. Analytische Theorie der Organischen Entwicklung/Analytic Theory of Organic Development. Leipzig: Verlag Von Wilhelm Engelman. 1984

- ^ Gordon, R. Brodland, GW. The cytoskeletal mechanics of brain morphogenesis: cell state splitters cause primary neural induction. Gell Biophys. 11: 177-238. (1987)

- ^ Brodland, GW" Gordon, R, Scott MJ, Bjorklund NK, Luchka KB, Martin, CC, Matuga, C., Globus, M., Vethamany-Globus S. and Shu, D. Furrowing surface contraction wave coincident with primary neural induction in amphibian embryos. J Morphol. 219: 131-142. 1994

- ^ Gordon, NK, Gordon R The organelle of differentiation in embryos: the cell state splitter Theor Biol Med Model (2016) 13: 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12976-016-0037-2

- ^ Björklund, NK, Gordon, R A hypothesis linking low folate intake to neural tube defects due to failure of post-translation methylations of the cytoskeleton International Journal of Developmental Biology 50 (2-3), 135-141

- ^ The Hierarchical Genome and Differentiation Waves. Series in Mathematical Biology and Medicine. Vol. 3. World Scientific Publishing Company. 1999. doi:10.1142/2755. ISBN 978-981-02-2268-0.

- ^ Burnside. M. B. Microrubules and microfilaments in amphibian neurulation. Alii. Zool. 13, 989-1006 1973

- ^ Jacobson, A.G. & R. Gordon. Changes in the shape of the developing vertebrate nervous system analyzed experimentally, mathematically and by computer simulation. J. Exp. Zool. 197, 191-246. 1973

- ^ Bordzilovskaya, N.P., T.A. Dettlaff, S.T. Duhon & G.M. Malacinski (1989). Developmental-stage series of axolotl embryos [Erratum: Staging Table 19-1 is for 20°C, not 29°C]. In: J.B. Armstrong & G.M. Malacinski (eds.), Developmental Biology of the Axolotl, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 201-219.

- ^ Youman's Neurological Surgery, H Richard Winn, 6th ed. Volume 1, p 81, 2011 Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA

- ^ Gilbert, SF (2000). "12: Formation of the Neural Tube". Developmental Biology (6 ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b Gilbert, SF (2013). "10: Emergence of the Ectoderm". Developmental Biology (10 ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-978-7. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Golden J A, Chernoff G F. Intermittent pattern of neural tube closure in two strains of mice. Teratology. 1993;47:73–80.

- ^ Van Allen M I, 15 others Evidence for multi-site closure of the neural tube in humans. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993;47:723–743.

- ^ Shepard, Thomas H. (1989). "Developmental stages in human embryos. R. O'Rahilly and F. Müller (Eds), Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC, 1987, 306 pp., $52". Teratology. 40: 85. doi:10.1002/tera.1420400111.

- ^ Formation of the Neural Tube Developmental Biology NCBI Bookshelf

- ^ Shimokita, E; Takahashi, Y (April 2011). "Secondary neurulation: Fate-mapping and gene manipulation of the neural tube in tailbud". Development, Growth & Differentiation. 53 (3): 401–10. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01260.x. PMID 21492152.

- ^ Pang, Dachling; Zovickian, John (2011). ""Retained medullary cord in humans: late arrest of secondary neurulation"". Neurosurgery. 68 (6): 1500–19. doi:10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820ee282. PMID 21336222. S2CID 25638763.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Scott F.; College, Swarthmore; Helsinki, the University of (2014). Developmental biology (Tenth ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. ISBN 978-0-87893-978-7.

- ^ Eric R. Kandel, ed. (2006). Principles of neural science (5. ed.). Appleton and Lange: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ Rakic, P (October 2009). "Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (10): 724–35. doi:10.1038/nrn2719. PMC 2913577. PMID 19763105.

- ^ Dehay, C; Kennedy, H (June 2007). "Cell-cycle control and cortical development". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (6): 438–50. doi:10.1038/nrn2097. PMID 17514197. S2CID 1851646.

- ^ Paraxial Mesoderm: The Somites and Their Derivatives NCBI Bookshelf, Developmental Biology 6th edition. Accessed Nov 29,2017

- ^ Daley, Darrel. Formation of the Nervous System Archived 2008-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. Last accessed on Oct 29, 2007.

- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "Anencephaly". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ CDC (2018-08-31). "Spina Bifida Facts | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

Further reading

[edit]- Almeida, Karla L.; et al. (2010). "Neural Induction". In Henning, Ulrich (ed.). Perspectives of Stem Cells: From Tools for Studying Mechanisms of Neuronal Differentiation Towards Therapy. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-3374-1.

- Basch, Martín L.; Bonner-Fraser, Marianne (2006). "Neural Crest Inducing Signals". In Saint-Jennet, Jean-Pierre (ed.). Neural crest induction and differentiation. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-35136-0.

- Harland, Richard M. (1997). "Neural induction in Xenopus". In Cowan, W. Maxwell (ed.). Molecular and cellular approaches to neural development. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511166-8.

- Ladher, Raj; Schoenwolf, Gary C. (2004). "Making a neural tube". In Jacobson, Marcus; Rao, Mahendra S. (eds.). Developmental neurobiology. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-48330-1.

- Tian, Jing; Sampath, Karuna (2004). "Formation and Functions of the Floor Plate". In Gong, Zhiyuan; Korzh, Vladimir (eds.). Fish development and genetics: the zebrafish and medaka models. World Scientific. pp. 123, 139–140. ISBN 978-981-238-821-6.

- Zhang, Su-Chun (2005). "Neural specification from human embryonic stem cells". In Odorico, John S.; et al. (eds.). Human embryonic stem cells. Garland Science. ISBN 978-1-85996-278-7.

External links

[edit]- Overview at uvm.edu

- Neurulation Animation Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

Neurulation

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Significance

Neurulation is the embryonic developmental process in vertebrates by which the neural plate, a layer of ectodermal cells, folds inward to form the neural tube, the primordial structure of the central nervous system (CNS).[3] This folding involves the elevation and fusion of neural folds along the midline, resulting in a hollow tube that will differentiate into the brain and spinal cord.[2] The process primarily occurs during gastrulation and the early stages of organogenesis, engaging neuroepithelial cells derived from the ectoderm.[4] In human embryogenesis, neurulation commences around the third week post-fertilization, with the neural plate appearing by day 18 and the anterior neuropore closing by day 25, followed by posterior closure around day 28.[2] This timing is critical, as the neural tube's formation establishes the foundational dorsal-ventral axis of the CNS, organizing regional identities that guide subsequent neuronal differentiation and connectivity.[5] Disruptions during this phase, such as failure of neural tube closure, lead to severe congenital anomalies known as neural tube defects, including spina bifida and anencephaly, affecting approximately 1 in 500 live births.[3] The significance of neurulation extends beyond immediate morphogenesis, as it represents a highly conserved mechanism across chordates, with dorsoventral patterning evident in non-vertebrate species like ascidians, suggesting evolutionary origins in a common ancestor predating the vertebrate lineage.[5] This conservation underscores neurulation's role in the evolutionary innovation of complex nervous systems, providing a blueprint for CNS development that has persisted through bilaterian evolution.[3]Primary vs. Secondary Neurulation

Neurulation in vertebrates proceeds through two distinct modes: primary and secondary, which differ in their spatial domains, cellular mechanisms, and evolutionary conservation. Primary neurulation forms the bulk of the neural tube in the anterior and trunk regions, while secondary neurulation generates the most posterior segments in the tail bud.[6] These processes ensure the topological continuity of the central nervous system, with primary neurulation forming the brain and spinal cord up to approximately the second sacral (S2) vertebral level, while secondary neurulation completes the lowermost sacral (S3-S5) and coccygeal portions in mammals, including humans.[7] Primary neurulation begins with the induction and thickening of the neural plate from the ectoderm, followed by its bending to form neural folds that elevate, adhere, and fuse dorsally to create a hollow neural tube. This process relies on epithelial shaping through apical constriction, convergent extension, and interkinetic nuclear migration within the neuroepithelium. It is a conserved mechanism across vertebrates for anterior neural tube formation, though site-specific variations exist, such as multi-site closure in mammals (e.g., three initiation points in mice) versus bi-directional zippering from two sites in birds. In amphibians like frogs, closure occurs more simultaneously along the axis.[6][8] In contrast, secondary neurulation forms the posterior neural tube without an initial neural plate or open folds; instead, mesenchymal cells in the tail bud condense into a solid neural rod, which then undergoes cavitation—a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition—to generate a central lumen and integrate with the primary neural tube. This internal process lacks the external folding and fusion steps of primary neurulation and is more uniform across species, occurring in the caudal region of mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles. However, it is modified in some groups, such as teleost fish, where a solid neural keel forms and then cavitates to generate the lumen, resembling secondary neurulation. In anurans like Xenopus, secondary neurulation contributes to the lumbar and tail neural tube via similar rod formation and canalization.[6][7][8] The mechanistic differences highlight primary neurulation's reliance on dynamic epithelial morphogenesis and epidermal-neural interactions for an open system of fold apposition, whereas secondary neurulation emphasizes mesenchymal aggregation and internal lumen formation without surface exposure. Spatially, primary processes dominate the rostral body axis universally, while secondary is restricted to the tail and varies in extent—prominent in tailed vertebrates but minimal or absent in some tailless species like certain urodeles. These distinctions underscore how evolutionary adaptations tailor neural tube formation to body plan diversity, with disruptions in either mode linked to region-specific neural tube defects.[6][8][7]Primary Neurulation

Neural Induction

Neural induction is the process by which the dorsal mesoderm, specifically the Spemann-Mangold organizer, specifies the overlying ectoderm to adopt a neural fate during early vertebrate embryogenesis. This phenomenon was first discovered through pioneering transplantation experiments conducted by Hans Spemann and Hilde Mangold in 1924, using amphibian embryos such as newts. In these studies, grafting the dorsal blastopore lip (the organizer region) from a donor embryo into the ventral ectoderm of a host induced the formation of a secondary embryonic axis, including neural tissue, demonstrating the organizer's inductive capacity. In amphibians like Xenopus laevis, neural induction occurs when the dorsal mesoderm, comprising the notochord and prechordal plate, signals to the overlying ectoderm to become neuroectoderm. This specification relies on the inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in the ectoderm, which otherwise promotes an epidermal fate. The organizer secretes key BMP antagonists—noggin, chordin, and follistatin—that bind to and sequester BMP4 and BMP7 ligands extracellularly, preventing their interaction with receptors on ectodermal cells and thereby allowing neural gene expression to proceed. Noggin was identified as a potent neural inducer that directly antagonizes BMP activity, inducing neural markers like NCAM in dissociated ectoderm cells. Similarly, chordin, expressed in the organizer, dorsalizes mesoderm and neuralizes ectoderm by blocking BMP signaling. Follistatin contributes by antagonizing BMP4, enhancing neural differentiation in a dose-dependent manner.[9] The core mechanism of BMP inhibition for neural induction is conserved across vertebrates, including amniotes such as birds and mammals, where the node (homologous to the amphibian organizer) secretes analogous antagonists to pattern the neural plate. In chick and mouse embryos, noggin and chordin from the node suppress BMP signaling in the ectoderm, promoting anterior neural fates. However, in teleosts like zebrafish, neural induction incorporates a planar signaling component, where BMP antagonists diffuse laterally within the ectodermal plane from midline sources during gastrulation, contributing to progressive neural specification along the anteroposterior axis. This results in the formation of a neural plate that will undergo subsequent morphological changes.[10]Neural Plate Formation

Following neural induction, the ectoderm destined for the nervous system undergoes a series of cellular and morphological transformations to form the neural plate, a flattened, thickened sheet of epithelium on the dorsal midline of the embryo. This structure emerges as a pseudostratified columnar epithelium, where neuroepithelial cells elongate along their apicobasal axis, increasing the plate's thickness relative to surrounding ectoderm. These changes occur progressively, beginning in the prospective hindbrain region and extending both cranially and caudally, ultimately spanning from the forebrain primordium to the level of the somites.[6] The thickening of the neural plate is driven by coordinated cellular behaviors, including apical constriction at the luminal surface and basolateral expansion of cells, which are mediated by actomyosin contractility involving non-muscle myosin II and actin filaments. Actomyosin generates contractile forces that narrow the apical domain while promoting lateral and basal expansion, thereby contributing to the overall pseudostratified morphology and mediolateral broadening of the plate. These dynamics are essential for establishing the plate's structural integrity prior to subsequent bending.[6][11] Additional contributions to plate formation come from interkinetic nuclear migration and oriented cell division, which enhance the pseudostratified organization and directed growth. During interkinetic nuclear migration, nuclei traverse the apicobasal axis of neuroepithelial cells in a cell cycle-dependent manner—moving basally during S-phase and apically during mitosis—creating a stratified appearance without true layering. Oriented cell divisions, with cleavage planes aligned to favor mediolateral expansion, further promote thickening along this axis, with approximately half of divisions contributing to plate elongation and broadening.[6][11] Following these changes, the midline of the neural plate invaginates to form the neural groove, with the lateral edges of the plate elevating to become the neural folds. This marks the progression in the sequence of primary neurulation: neural plate → neural groove → elevation and fusion of neural folds → closed neural tube.[2][3] Tissue interactions with the underlying mesoderm play a supportive role in these transformations, providing mechanical anchorage and tensile forces that stabilize the neural plate during its formation. The paraxial mesoderm, in particular, exerts physical forces that aid in maintaining the plate's position and shape amid the dynamic ectodermal changes. This mechanical interplay ensures the neural plate integrates properly with adjacent tissues as it develops.[6]Neural Fold Elevation and Fusion

During primary neurulation, elevation of the neural folds begins with the formation of midline hinge points in the neural plate, where neuroepithelial cells undergo shape changes to become wedge-like, featuring apical constriction and basal widening that facilitate inward bending of the epithelium.[12] This cellular remodeling is actomyosin-dependent, with non-muscle myosin II generating contractile forces that narrow the apical surface of midline cells, promoting the initial uplift of the folds.[13] Lateral aspects of the neural folds rise through additional bending at dorsolateral hinge points, which is aided by the expansion of the underlying paraxial mesoderm, increasing its surface area by approximately 58% in mouse embryos and exerting outward forces that elevate the plate edges.[12] As the neural folds elevate and converge toward the dorsal midline, their apices come into apposition, initiating fusion through cadherin-mediated adhesion between neuroepithelial cells.[2] N-cadherin, upregulated in the neural plate during this transition from E-cadherin expression, enables tight cell-cell contacts that seal the folds in a progressive, zipper-like manner along the anterior-posterior axis.[2] This zippering process relies on focal anchorage of the surface ectoderm to a fibronectin-rich basement membrane via integrin β1, which stabilizes the apposed edges and allows directional propagation of fusion.[14] In human embryos, fusion of the neural folds begins around day 22 in the cervical region, with the anterior neuropore closing around day 25 and the posterior neuropore around day 27–28, marking the initial enclosure of the rostral and caudal neural tube regions.[3] Research from 2020 has illuminated the dynamic nature of these events in mammalian models, demonstrating that pulsatile contractions of apical actomyosin networks drive the asynchronous wedging of neuroepithelial cells, enabling coordinated fold elevation without synchronous cell behavior that could disrupt tissue integrity.[15] These oscillations, observed in mouse embryos, contribute to the progressive apical constriction required for hinge point formation and overall tube morphogenesis.[15]Neural Tube Closure

Neural tube closure represents the final phase of primary neurulation, where the apposed neural folds fuse along the dorsal midline to form a continuous tube, sealing the neuroepithelium from the surface ectoderm. This process begins in the mid-trunk region of the embryo, typically at the hindbrain-cervical boundary, and proceeds progressively in a zipper-like manner both cranially and caudally from multiple initiation sites. In mammalian embryos, such as mice, closure initiates at distinct points: closure 1 at the hindbrain-cervical junction, closure 2 at the forebrain-midbrain boundary, and closure 3 in the rostral forebrain, with fusion propagating bidirectionally to enclose the neural plate.[16] The fusion involves intimate contact between the neural folds, facilitated by cellular protrusions and adhesion molecules that bridge the gap, ensuring the neuroepithelium is isolated from the external environment.[17] The mechanics of closure rely on epithelial remodeling within the neuroepithelium and overlying non-neural ectoderm, including changes in cell shape from cuboidal to wedge-like at hinge points and apical constriction to drive fold apposition. Extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition plays a crucial role, with components such as fibronectin and laminin isoforms accumulating between the neuroepithelium and surface ectoderm to provide structural support and modulate cell adhesion during fusion. These processes culminate in key temporal events: the anterior neuropore closes at approximately the 20-somite stage, while the posterior neuropore seals at the 29- to 30-somite stage, marking the completion of primary neurulation in the spinal cord region. Failure at these closure points can disrupt tube formation, though the precise molecular triggers vary by axial level.[16][18][19] Following successful closure, the neural tube detaches from the overlying ectoderm through differential expression of adhesion molecules, such as a shift from E-cadherin in the surface ectoderm to N-cadherin and N-CAM in the neuroepithelium, allowing the cutaneous ectoderm to disjoin from the neuroectoderm without disrupting integrity. This detachment coincides with the differentiation of the surface ectoderm into a stratified epithelium, including the formation of a superficial periderm layer that acts as a protective barrier. Internally, the enclosed neuroepithelium establishes a central lumen through cavitation and fluid accumulation, which expands to form the ventricles of the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord, setting the stage for subsequent central nervous system patterning.[3][2]Patterning of the Neural Tube

Following neural tube closure in primary neurulation, the neuroepithelium undergoes patterning along its dorsoventral (DV) and anteroposterior (AP) axes to establish regional identities that give rise to diverse neuronal subtypes. DV patterning primarily occurs through opposing signaling gradients that specify ventral and dorsal progenitor domains. In the ventral neural tube, Sonic hedgehog (Shh) secreted from the notochord and induced in the floor plate acts as a morphogen to pattern progenitor domains in a concentration-dependent manner, promoting the specification of motor neurons and ventral interneurons. High Shh levels induce the p3 domain, generating V3 interneurons, while progressively lower concentrations specify p2 (V2 interneurons), p1 (V1 interneurons), and p0 (V0 interneurons) domains from ventral to more dorsal positions.[21] Dorsal patterning is driven by bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and Wnts emanating from the roof plate, which induce sensory interneuron progenitors. BMP signaling from the roof plate specifies the dorsal-most dI1 domain (dorsal interneurons 1, giving rise to proprioceptive relay neurons), with graded activity patterning dI2 through dI6 domains that produce touch, pain, and temperature-sensing interneurons. Wnt ligands, co-expressed in the roof plate, cooperate with BMPs to refine dorsal identities and promote proliferation of dorsal progenitors.[22] These DV signals begin during neural plate folding, prior to tube closure, establishing progenitor domains that persist into the closed neural tube.[23] AP patterning establishes rostrocaudal identities along the neural tube, primarily through Hox gene clusters whose expression is regulated by posteriorizing gradients. Hox genes, such as HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD paralogs, are expressed in nested domains that confer segmental identities, with anterior limits determining hindbrain, cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions.[24] Posterior gradients of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and Wnt signaling from the primitive streak and tail bud promote Hox activation and posterior ectoderm fate, while retinoic acid (RA) synthesized in the somites reinforces posterior Hox expression and restricts anterior fates. For instance, FGF8 and Wnt3a induce posterior Hox genes like Hoxb4 and Hoxb6, counteracting anteriorizing cues.[25] AP patterning initiates during neural tube closure and continues post-closure, integrating with DV signals to define discrete neurogenic domains.[26]Secondary Neurulation

Mechanism in the Caudal Region

Secondary neurulation forms the posterior portion of the neural tube through a non-folding process in the caudal region of the embryo. In this mechanism, mesenchymal cells within the caudal eminence, or tail bud, aggregate and condense to create a solid mass known as the medullary cord or neural rod. This structure then undergoes cavitation, a central hollowing that establishes the lumen of the neural tube. Unlike the elevation and fusion of neural folds in primary neurulation, this process relies on mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions to shape the tube.[3][27] The cellular events begin with an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cells derived from the epiblast and presomitic mesoderm, enabling them to delaminate and migrate into the tail bud mesenchyme. These mesenchymal cells then cluster beneath the overlying ectoderm, undergoing epithelialization to form the compact neural rod through cell aggregation and adhesion. Cavitation follows, where intracellular vacuoles coalesce and connect to form the ependymal canal, hollowing the rod from its center outward. This sequence ensures the formation of a continuous neural tube without surface closure events.[28][29] Species variations highlight differences in prominence and execution of this process. In mice, secondary neurulation is robust and extends prominently into the tail, initiating around the level of somite 35 after posterior neuropore closure, involving a single rosette-like condensation structure. In humans, the process contributes primarily to the lowermost spinal cord segments and follows a similar pattern to that in mice, involving mechanisms such as neural tube splitting in approximately 60% of proximal tail regions; primary neurulation typically reaches the S2 vertebral level, with secondary neurulation completing the cord below S2 and forming structures like the filum terminale.[3][7][30][31]Integration with Primary Neural Tube

The integration of the secondary neural tube with the primary neural tube occurs via a specialized mechanism termed junctional neurulation, which establishes topological and functional continuity between the two structures following the completion of primary neurulation. This process begins after the posterior neuropore—the caudal opening of the primary neural tube—closes, typically marking the transition to secondary neurulation in the caudal embryonic region. Junctional neurulation involves the rostral attachment of the secondary neural tube, derived from the caudal rod, to the closed posterior end of the primary tube, ensuring seamless luminal alignment and cellular integration without gaps in the developing spinal cord.[32] Central to this fusion is the role of cell adhesion molecules, such as cadherins, which mediate the adhesion between neuroepithelial cells of the primary and secondary tubes, allowing for precise apposition and merging of their walls. The lumens of both tubes align through coordinated cavitation and remodeling, forming a continuous central canal that extends the neural tube's architecture caudally.[32] The resulting continuity forms a unified central nervous system spanning from the forebrain to the coccygeal levels, critical for coordinated neural signaling and spinal cord functionality. Disruptions in junctional neurulation, such as impaired cell adhesion, can lead to junctional neural tube defects (JNTD), characterized by a disconnected or split spinal cord at the junction, often associated with neural tube defects.[33] In human embryos, this integration follows primary neural tube closure around embryonic day 28 (approximately Carnegie stage 12), with secondary neurulation and junctional processes extending into subsequent days to complete the caudal spinal cord by the end of the fourth week. The caudal rod, formed earlier through aggregation of mesenchymal cells undergoing mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, provides the cellular substrate for this attachment.[1][32]Derivatives of the Neural Tube

Central Nervous System Formation

Following the closure of the neural tube during the third and fourth weeks of human embryonic development, the anterior portion begins to differentiate into the brain through a process of dilation and segmentation. By the end of the fourth week, this region expands to form three primary brain vesicles: the prosencephalon (forebrain), mesencephalon (midbrain), and rhombencephalon (hindbrain). These vesicles arise from localized proliferation and fluid accumulation within the neural tube lumen, establishing the foundational compartments that will further subdivide; for instance, the prosencephalon will later develop into the telencephalon and diencephalon, while the rhombencephalon gives rise to the metencephalon and myelencephalon.[2][34] After fusion and closure of the neural tube, the cutaneous ectoderm disjoins from the neuroectoderm, allowing paraxial mesenchyme to interpose dorsally. This paraxial mesenchyme subsequently differentiates into somites, which contribute to the formation of meninges, vertebrae from the sclerotome, and paraspinal muscles from the myotome.[2][35][36] In contrast, the posterior region of the neural tube elongates more uniformly to form the spinal cord, without the pronounced vesicular expansions seen anteriorly. This elongation occurs concurrently with somitogenesis and axial growth, resulting in a cylindrical structure whose central lumen becomes the narrow central canal. Early in this process, the lateral walls of the spinal cord (and brainstem) thicken and divide along the midline into dorsal alar plates, which primarily generate sensory neurons, and ventral basal plates, which produce motor neurons; these plates are separated by the sulcus limitans, a longitudinal groove that delineates sensory and motor domains.[2][34] Throughout these differentiations, the initial cellular events involve rapid proliferation of neuroepithelial cells in the ventricular zone lining the neural tube, leading to the generation of neurons that migrate outward to form the mantle zone. This neurogenesis peaks early and is followed by gliogenesis, where radial glial cells and other progenitors produce astrocytes and oligodendrocytes to support neuronal function and myelination. The hindbrain, in particular, represents an evolutionarily conserved feature among chordates, retaining segmented rhombomeres that specify cranial nerve identities and reflect ancient patterning mechanisms shared with invertebrate chordates like amphioxus.[2][34][37]Neural Crest Cells

Neural crest cells originate from the dorsal region of the neural folds and early neural tube during neurulation in vertebrate embryos. These cells arise at the neural plate border, a transitional zone between the neural plate and non-neural ectoderm, where they undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to acquire migratory properties. This EMT process is driven by bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, which establishes the neural plate border competence and induces neural crest specification at intermediate levels, modulated by antagonists like Chordin. Transcription factors such as Snail (Snai1/2) are upregulated by BMP and Wnt signals, repressing E-cadherin to facilitate delamination and enable the cells to become multipotent mesenchymal progenitors.[38][39][40] Following delamination, neural crest cells embark on extensive migrations along defined pathways, guided by extracellular matrix cues and inhibitory signals from surrounding tissues. In the trunk region, cells migrate ventromedially between the neural tube and somites to form the peripheral nervous system (PNS), including sensory and autonomic neurons (e.g., dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic chain) as well as glia like Schwann cells; a subset migrates dorsolaterally through the somites to generate melanocytes that populate the skin. Cranial neural crest cells follow more complex routes, invading the frontonasal prominence and pharyngeal arches to contribute to the craniofacial skeleton, including cartilage and bone derivatives. Additionally, trunk neural crest cells reach the adrenal medulla to form chromaffin cells, while all axial levels contribute to melanocytes via dorsolateral migration. These pathways ensure precise spatiotemporal delivery to target sites, with somites acting as permissive corridors segmented by Eph/ephrin signaling to prevent premature mixing.[41][42][43] Premigratory neural crest cells are specified toward their fates through axial-specific gene regulatory networks before migration begins. Wnt signaling, in concert with BMP and FGF, activates early specifiers like Msx1, Pax7, and Zic1 at the neural plate border, priming multipotency; subsequent Dlx genes (e.g., Dlx5) further refine cranial identity. Trunk neural crest cells are biased toward neurogenic and melanogenic lineages, differentiating into PNS neurons, glia, and dermal melanocytes, whereas cranial neural crest cells possess broader mesenchymal potential, forming cartilage, bone, and connective tissues of the face due to unique enhancers (e.g., Hox-independent regulation). This axial distinction arises from dorsally patterned cues that impose positional identity, ensuring diverse contributions without overlap in skeletogenic capacity between regions.[44][45][46]Non-Neural Ectoderm Derivatives

Distinct from the direct derivatives of the neural tube, the non-neural ectoderm, also known as surface or epidermal ectoderm, comprises the portions of the embryonic ectoderm flanking the neural plate that do not contribute to neural structures. During gastrulation and early neurulation, this tissue is specified through gradients of signaling molecules, adopting fates distinct from the neural ectoderm. Its primary derivatives include the epidermis and associated appendages, forming essential protective and sensory components of the integumentary system.[47] The lateral non-neural ectoderm differentiates into the stratified squamous epithelium of the epidermis through a process of proliferation, stratification, and keratinization. Initially, at the end of the fourth week of human embryonic development, following neural tube separation, the surface ectoderm forms a single layer of cuboidal basal cells atop the underlying mesenchyme, which will become the dermis. By the fifth week, proliferation generates a superficial periderm layer of squamous cells, providing transient protection via secretion of vernix caseosa. Progressive stratification occurs by week 11, yielding multiple layers: the stratum germinativum (basal proliferative layer), stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and eventually the keratinized stratum corneum by week 20. Keratinization involves the synthesis of intermediate filament keratins (e.g., K1 and K10) and their bundling with filaggrin in granular cells, culminating in enucleation and dehydration to form a tough, impermeable barrier. This process is regulated by transcription factors such as p63 and involves calcium-dependent desmosomal junctions for structural integrity.[48][48] Epidermal appendages, including hair follicles, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and nails, arise as localized thickenings of the basal epidermis starting around weeks 9–12. Hair follicles form via epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, where placode-like buds invaginate into the dermis, inducing dermal papillae that drive cyclic growth and keratin production in hair shaft cells. Sweat glands develop similarly from epidermal buds extending into the dermis, differentiating into secretory coils and ducts by the sixth month, essential for thermoregulation. Nails originate from nail matrix cells in the distal phalanges, with keratinized plate formation beginning at week 10. These structures enhance the epidermis's multifunctional role, providing insulation, lubrication, and sensory capabilities.[47][48] Post-neural tube closure, the non-neural ectoderm directly overlies the closed neural tube, remodeling into a continuous epithelial sheet that covers the central nervous system. This positioning ensures physical separation and protection, with the epidermis serving as the outermost barrier against environmental stressors. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling plays a critical role in promoting this epidermal fate by inhibiting neural specification; BMP4, for instance, upregulates transcription factor AP2γ via Smad1/5/8-mediated pathways, driving expression of epidermal markers like cytokeratin 14 while suppressing neural genes such as Sox1. In the absence of BMP antagonism (e.g., from noggin or chordin in neural regions), high BMP levels in lateral ectoderm enforce commitment to stratified epithelium.[1][49] In the head region, non-neural ectoderm contributes to sensory structures, notably the lens placode, which forms within the anterior pre-placodal ectoderm around the optic vesicle. Specified by Pax6 and Six3 transcription factors under influence of BMP, retinoic acid, and Wnt inhibition, the lens placode thickens and invaginates to generate the lens vesicle, differentiating into epithelial and fiber cells essential for refraction and vision. This derivation highlights the ectoderm's versatility in forming neuroectoderm-adjacent tissues without direct neural contribution.[50] Overall, the non-neural ectoderm's derivatives fulfill vital developmental roles, primarily establishing the skin's barrier function to prevent dehydration, infection, and mechanical injury, while minimally influencing central nervous system architecture. Through epidermal integrity and appendage formation, it supports homeostasis, sensory perception (e.g., via Merkel cells in the epidermis), and integration with peripheral systems, underscoring its indispensable role in vertebrate embryogenesis.[47][48]Molecular and Genetic Regulation

Key Signaling Pathways

The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in neural induction and dorsoventral patterning during neurulation. In the ectoderm, BMP ligands, such as BMP4 and BMP7, promote epidermal fate, but their activity is antagonized dorsally by secreted inhibitors like noggin and chordin, which are expressed in the Spemann organizer and notochord. This inhibition of BMP signaling allows the default neural fate to emerge in the dorsal neural plate, as demonstrated in Xenopus embryos where noggin directly binds BMPs to prevent their interaction with receptors, thereby inducing neural tissue independently of mesoderm. Similarly, chordin, another organizer-derived antagonist, binds BMPs with high affinity and facilitates neural induction by establishing a dorsal low-BMP gradient. Post-induction, BMP signaling is reactivated in the dorsal neural tube to specify dorsal identities, such as sensory neuron progenitors, through graded receptor activation.[51] Sonic hedgehog (SHH), secreted from the notochord and floor plate, establishes a ventral-to-dorsal morphogen gradient that patterns the neural tube along the dorsoventral axis. High SHH concentrations (e.g., ~20 nM in vitro) induce floor plate cells, while lower levels (around 4-5 nM) specify motor neuron progenitors, and even lower levels promote ventral interneuron fates, with the gradient interpreted via concentration-dependent thresholds.[52] This patterning involves SHH binding to Patched receptors, relieving inhibition of Smoothened, and activating Gli transcription factors, where Gli3 primarily acts as a repressor in dorsal regions and Gli2/3 activators ventrally. The pathway's role is conserved across vertebrates, as evidenced by chick and mouse studies showing SHH's necessity for ventral cell type induction.[53] Additional signaling pathways contribute to anteroposterior identity and proliferation during neurulation. Wnt signaling, particularly canonical β-catenin-dependent pathways, promotes posterior neural fates by posteriorizing the neural plate, with gradients of Wnt3a and Wnt8 establishing Hox gene expression domains for caudal identity. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling, via ligands like FGF8 from the primitive streak, drives neural progenitor proliferation and maintains the neural plate's mitotic state, counteracting differentiation signals. Retinoic acid (RA), derived from somites, patterns the posterior neural tube at somite levels by inducing Hox genes and opposing FGF to terminate posterior growth. These pathways interact dynamically; notably, SHH and BMP exhibit mutual antagonism in dorsoventral patterning, where BMP inhibitors enhance SHH's ventralizing effects, ensuring balanced neural tube specification.[54]Transcription Factors and Gene Expression

Transcription factors play a pivotal role in interpreting extracellular signals during neurulation to establish and maintain neural progenitor identities along the dorsoventral and anteroposterior axes of the neural tube. These proteins regulate gene expression programs that specify distinct progenitor domains, ensuring precise patterning of the central nervous system. Key transcription factors such as Sox2, Pax6, Pax7, and Olig2 are essential for neural maintenance and domain-specific differentiation, while others like Irx3 and Hox cluster genes define dynamic expression patterns that confer segmental and positional identities.[55] Sox2, a member of the SOXB1 family, is crucial for maintaining the multipotent state of neural progenitors throughout neurulation, preventing premature differentiation and supporting the expansion of the neural plate. Its expression is initiated early in the neuroectoderm and persists in the ventricular zone of the forming neural tube, where it cooperates with other factors to reinforce neural fate. In contrast, Pax6 and Pax7 contribute to anteroposterior patterning by delineating domain boundaries; Pax6 is expressed in forebrain and anterior spinal cord progenitors, promoting telencephalic and diencephalic identities, while Pax7 marks midbrain-hindbrain and posterior spinal domains, restricting anterior fates and supporting mid-hindbrain development. Olig2, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, specifies ventral progenitors in the pMN domain, directing the generation of motor neurons during early neurogenesis and later transitioning to oligodendrocyte precursors in the ventral spinal cord.[56][57][58] Expression patterns of these factors exhibit dynamic domains that refine progenitor identities over time. For instance, Irx3 is restricted to the p2 progenitor domain dorsal to the pMN boundary, where it represses Olig2 to prevent motor neuron fate and promotes V2 interneuron specification through cross-repressive interactions. Hox cluster genes, organized in four paralogous groups (HoxA-D), establish segmental identity along the anteroposterior axis, with overlapping expression codes in hindbrain rhombomeres and spinal cord segments that dictate neuronal subtype diversification and connectivity. These patterns emerge progressively after neural tube closure, integrating positional cues to generate a topographic map of the nervous system.[59][60] Regulatory networks involving these transcription factors form intricate feedback loops to stabilize ventralization and domain boundaries. Upstream signals like Sonic hedgehog (Shh) induce Foxa2 expression in floor plate progenitors, and Foxa2 in turn reinforces Shh signaling by binding enhancers to maintain ventral midline identity and propagate the gradient. Such loops, including Shh-Foxa2 mutual reinforcement, ensure robust interpretation of morphogen gradients into stable gene expression profiles across progenitor domains.[61][62]Neural Tube Defects

Types and Etiology

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are classified based on whether the defect is open or closed, as well as its location along the neural axis, such as cranial or spinal regions. Open NTDs occur when the neural tube fails to close completely, resulting in exposure of neural tissue to the external environment through a skin defect.[63] These include anencephaly, a severe cranial defect characterized by absence of the cerebral hemispheres and vault of the skull due to failure of anterior neuropore closure, and myelomeningocele, the most common form of open spina bifida, where spinal neural tissue protrudes through an open vertebral defect.[64][65] In contrast, closed NTDs involve a vertebral defect covered by skin or other tissue, without direct exposure of neural elements, such as occult spina bifida (a mild spinal form with no neurological symptoms) or meningocele (a sac-like protrusion of meninges).[66] Cranial NTDs, like anencephaly and encephalocele (protrusion of brain tissue through a skull defect), arise from disruptions in rostral neural tube closure, while spinal NTDs, primarily spina bifida variants, stem from caudal closure failures.[67] The etiology of NTDs is multifactorial, involving interactions between genetic predispositions and environmental influences that disrupt primary neurulation or secondary neurulation processes.[68] Genetic factors include polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene, such as the C677T variant, which impairs folate metabolism and increases NTD risk, particularly in homozygous individuals.[69] Environmental contributors encompass maternal folate deficiency, which hinders DNA synthesis and methylation critical for neural tube closure, and exposure to teratogens like the anticonvulsant valproic acid (valproate), which interferes with folate uptake and neural development.[69][70] Other risks include diabetes, obesity, and certain medications, often culminating in failures of neural fold elevation, fusion, or induction during the critical 3-4 week embryonic period.[68] Globally, NTDs affect approximately 1 to 5 per 1,000 births, with an estimated 300,000 cases annually, though prevalence varies by region due to genetic, dietary, and socioeconomic factors.[71] Rates are higher in certain populations, such as those in Ireland, where historical prevalence reached up to 23 per 10,000 births in the 1980s, linked to lower folate intake and genetic susceptibilities.[72]Prevention and Clinical Management

Prevention of neural tube defects (NTDs) primarily focuses on folic acid supplementation and food fortification. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all individuals planning or capable of pregnancy take a daily folic acid supplement of 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), starting at least one month before conception and continuing through the first two to three months of pregnancy, as this regimen reduces the risk of NTDs by approximately 50% or more.[73][74] Similarly, the World Health Organization advises 400 μg of folic acid daily from the time of attempting conception until 12 weeks of gestation to achieve comparable preventive benefits.[75] Mandatory folic acid fortification of enriched cereal grains, initiated in the United States in 1998 and adopted in various countries since the late 1990s, has led to a 50% lower prevalence of NTDs in regions with such policies, with some studies reporting reductions up to 70%.00543-6/fulltext)[76] In the US, this fortification averted an estimated 1,326 NTD-affected births annually from 1999 to 2011, corresponding to a 35% decline in prevalence compared to pre-fortification levels.[77] Prenatal diagnosis of NTDs relies on a combination of screening and confirmatory tests to enable early intervention. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) screening, typically performed between 15 and 20 weeks of gestation, detects elevated AFP levels associated with open NTDs, with a sensitivity of about 80-90% when combined with other methods.[78] Detailed fetal ultrasound, offered to all pregnant individuals around 18-20 weeks, visualizes spinal and cranial defects with high accuracy, serving as the primary diagnostic tool for NTDs.[79] If screening suggests an NTD, amniocentesis can confirm the diagnosis by analyzing amniotic fluid for AFP and acetylcholinesterase, providing near-100% specificity for open defects.[79] Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used subsequently to assess lesion severity, brain involvement, and associated anomalies, aiding in prognosis and management planning.[80] Clinical management of NTDs, particularly myelomeningocele, involves timely surgical intervention and lifelong multidisciplinary support. Prenatal surgical repair, performed via open fetal surgery between 19 and 26 weeks of gestation, closes the spinal defect in utero and has been shown to reduce the incidence of ventriculoperitoneal shunting for hydrocephalus by 40-60% and improve lower extremity motor function at 30 months, though it carries maternal risks such as preterm labor and uterine dehiscence.[81][82] Postnatal repair, conducted within 24-48 hours after birth, remains the standard approach, effectively covering the exposed neural placode to prevent infection and further damage while preserving neurologic potential.[83] Long-term care requires a multidisciplinary team, including neurosurgeons for ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement to manage hydrocephalus (needed in up to 80% of cases), orthopedists for mobility aids and spinal stabilization, urologists for neurogenic bladder, and rehabilitation specialists to optimize quality of life.[84][82]References

- https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199611)207:3<309::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-L