Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Eureka Rebellion

View on Wikipedia

| Part of the Victorian gold rush | |

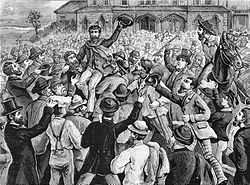

Eureka Stockade Riot by John Black Henderson, 1854 | |

| |

| Date | 1851–1854 |

|---|---|

| Location | Colony of Victoria |

| Participants | Gold miners and the Victorian colonial government |

| Outcome |

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eureka Rebellion |

|---|

|

|

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The Eureka Rebellion involved gold miners who revolted against the British administration of the colony of Victoria, Australia, during the Victorian gold rush.[1] It culminated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, which took place on 3 December 1854 at Ballarat between the rebels and the colonial forces of Australia. The fighting resulted in an official total of 27 deaths and many injuries, the majority of casualties being rebels. There was a preceding period beginning in 1851 of peaceful demonstrations and civil disobedience on the Victorian goldfields. The miners had various grievances, chiefly the cost of mining permits and the officious way the system was enforced.[2][3]

Tensions began in 1851, with the introduction of a tax on gold mines. Miners began to organise and protest the taxes; miners stopped paying the taxes en masse. The October 1854 murder of a gold miner, and the burning of a local hotel (which miners blamed on the government), ended the previously peaceful nature of the miners' dispute. Open rebellion broke out on 29 November 1854, as a crowd of some 10,000 swore allegiance to the Eureka Flag. Gold miner Peter Lalor became the rebellion's de facto leader, as he had initiated the swearing of allegiance. The Battle of Eureka Stockade ended the short-lived rebellion on 3 December. A group of 13 captured rebels (not including Lalor, who was in hiding) was put on trial for high treason in Melbourne, but mass public support led to their acquittal.

The legacy of the Rebellion is contested. Rebel leader Peter Lalor was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly in 1856, though he proved to be less of an ally to the common man than expected.[vague] Several reforms sought by the rebels were subsequently implemented, including legislation providing for universal adult male suffrage for Assembly elections and the removal of property qualifications for Legislative Assembly members. The Eureka Rebellion is controversially identified with the birth of democracy in Australia and interpreted by many as a political revolt.[4][5]

Origins in the Victorian gold rush

[edit]The Eureka Rebellion had its origins in the Australian gold rush that began in 1851. Following the separation of Victoria from New South Wales on 1 July 1851, gold prospectors were offered 200 guineas for making discoveries within 320 kilometres (200 mi) of Melbourne.[6] In August 1851, the news was received around the world that, on top of several earlier finds, Thomas Hiscock had found still more deposits 3 kilometres (2 mi) west of Buninyong.[7]

This led to gold fever taking hold as the colony's population increased from 77,000 in 1851 to 198,496 in 1853.[8] In three years, the total number of people living in and around the Victorian goldfields stood at a 12-month average of 100,351. In 1851, the Australian population was 430,000. In 1871, it was 1.7 million.[9] Among this number was "a heavy sprinkling of ex-convicts, gamblers, thieves, rogues and vagabonds of all kinds".[10] The local authorities soon found themselves with fewer police and lacked the infrastructure needed to support the expansion of the mining industry. The number of public servants, factory and farm workers leaving for the goldfields to seek their fortune made for chronic labour shortages that needed to be resolved.[11]

Protests on the goldfields: 1851–1854

[edit]La Trobe introduces monthly mining tax as protests begin

[edit]

On 16 August 1851, just days after Hiscock's lucky strike, Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe issued two proclamations that reserved to the crown all land rights to the goldfields and introduced a mining licence (tax) of 30 shillings per month, effective 1 September.[12][13] The universal mining tax was based on time stayed rather than what was seen as the more equitable option, an export duty levied only on gold found, meaning it was always designed to make life unprofitable for most prospectors.[11][14]

There were several mass public meetings and miners' delegations in the years leading up to the armed revolt. The earliest rally was held on 26 August 1851 at Hiscock's Gully in Buninyong and attracted 40–50 miners protesting the new mining regulations, and four resolutions to this end were passed.[15] From the outset, there was a division between the "moral force" activists who favoured lawful, peaceful and democratic means and those who advocated "physical force", with some in attendance suggesting that the miners take up arms against the lieutenant governor, who was irreverently viewed as a feather-wearing, effeminate fop.[16] This first meeting was followed by ongoing protests across all the colony's mining settlements in the years leading up to the 1854 armed uprising at Ballarat.

First gold commissioner arrives in Ballarat

[edit]

In mid-September 1851, D. C. Doveton, the first local gold commissioner appointed by La Trobe, arrived in Ballarat.[17] At the beginning of December, there was discontent when it was announced that the licence fee would be raised to 3 pounds a month, a 200 per cent increase, effective 1 January 1852.[18] In Ballarat, some miners became so agitated that they began to gather arms.[19] On 8 December, the rebellion continued to build momentum with an anti-mining tax banner put on public display at Forrest Creek.[20]

After remonstrations, particularly in Melbourne and Geelong, on 13 December 1851, the previous increase was rescinded. The Forest Creek Monster Meeting took place at Mount Alexander on 15 December 1851. This was the first truly mass demonstration of the Eureka Rebellion. According to high-end estimates, up to 20,000 miners turned out in a massive display of support for repealing the mining tax.[21] The only pictorial evidence concerning the flag on display at the meeting is an engraving of the scene by Thomas Ham and David Tulloch that features only part of the design.[21]

Based on the research of Doug Ralph, Marjorie Theobald and others have questioned whether there was an iconic Digger's flag displayed at Forest Creek that spread to other mining settlements.[22][23]

Two days later, it was announced that La Trobe had reversed the planned increase in the mining tax. The oppressive licence hunts continued and increased in frequency, causing general dissent among the diggers.[24] There was strong opposition to the strict prohibition of liquor imposed by the government at the goldfields settlements, whereby the sale and consumption of alcohol were restricted to licensed hotels.[25][26]

Despite the high turnover in population on the goldfields, discontent continued to simmer throughout 1852.[27] La Trobe received a petition from the people of Bendigo on 2 September 1852, drawing attention to the need for improvements in the road from Melbourne. The lack of police protection was also a major issue for the protesting miners. On 14 August 1852, a fight broke out among 150 men over land rights in Bendigo. An inquiry recommended increasing police numbers in the colony's mining settlements. Around this time, the first gold deposits at the Eureka lead in Ballarat were found.[27]

In October 1852, at Lever Flat near Bendigo, the miners attempted to respond to rising crime levels by forming a "Mutual Protection Association". They pledged to withhold the licence fee, build detention centres, and begin nightly armed patrols, with vigilantes dispensing summary justice to those suspected of criminal activities. That month, Government House received a petition from Lever Flat, Forrest Creek and Mount Alexander about policing levels as the colony continued to strain due to the gold rush. On 25 November 1852, a police patrol was attacked by a mob of miners who wrongly believed they were obliged to take out a whole month's subscription for seven days at Oven's goldfield in Bendigo.[28]

In 1852, it was decided by the UK government that the Australian colonies should each draft their own constitutions, pending final approval by the Imperial parliament in London.[29]

Bendigo Petition and the Red Ribbon Movement

[edit]The disquiet on the goldfields continued in 1853, with public meetings held in Castlemaine, Heathcote and Bendigo.[30] On 3 February 1853, a policeman accidentally caused the death of William Guest at Reid's Creek. Assistant Commissioner James Clow had to defuse a difficult situation with a promise to conduct an inquiry into the circumstances. A group of one thousand angry miners overran the government camp and relieved the police of their sidearms and weapons, destroying a cache of weapons.[28] George Black assisted Dr John Owens in chairing a public meeting held at Ovens field on 11 February 1853 that called for the death of Guest to be fully investigated.[28]

The Anti-Gold Licence Association was formed in June at a meeting in Bendigo, where 23,000 signatures were collected for a mass petition, including 8,000 from the mining settlement at McIvor.[31]

There was an incident on 2 July 1853 in which police were assaulted in the vicinity of an anti-licence meeting at the Sandhurst goldfield in Bendigo, with rocks being thrown as they escorted an intoxicated miner to the holding cells.[28] On 16 July 1853, an anti-licence demonstration in Sandhurst attracted 6,000 people, who also raised the issue of lack of electoral rights. The high commissioner of the goldfields, William Wright, advised La Trobe of his support for an export duty on gold found rather than the existing universal tax on all prospectors based on time stayed.[32]

On 3 August, the Bendigo petition was placed before La Trobe, who refused to act on a request to suspend the mining tax again and give the miners the right to vote.[33] The next day, there was a meeting held at Protestant Hall in Melbourne where the delegation reported on the exchange with La Trobe. The crowd reacted with "loud disapprobation and showers of hisses" when the lieutenant governor was mentioned. Manning Clark speaks of one of the leaders of the "moral force" faction, George Thompson, who returned to Bendigo, where he attended another meeting on 28 July. Formerly, there was talk of "moral suasion" and "the genius of the English people to compose their differences without resort to violence". Thompson pointed to the Union Jack and jokingly said that "if the flag went, it would be replaced by a diggers' flag".[34]

The Bendigo "diggers flag" was unfurled at a rally at View Point, Sandhurst, on 12 August 1853 to hear from delegates who had returned from Melbourne with news of the failure of the Bendigo petition. The miners paraded under the flags of several nations, including the Irish tricolour, the saltire of Scotland, the Union Jack, revolutionary French and German flags, and the Stars and Stripes. The Geelong Advertiser reported that:

Gully after gully hoisted its own flag, around which the various sections rallied, and as they proceeded towards the starting points, formed quite an animated spectacle … But the flag which attracted the greatest attention was the Diggers' Banner, the work of one of the Committee, Mr Dexter, an artist of considerable talent, and certainly no company ever possessed a more appropriate coat of arms, or a motto more in character with themselves.

The design of the Digger's flag was along the same lines as the flag flown at Forrest Creek in 1851. It has four quarters that feature a pick, shovel and cradle, symbolising the mining industry; a bundle of sticks tied together, symbolising unity; the scales of justice, symbolising the remedies the miners sought; and a Kangaroo and Emu, symbolising Australia.[22]

On 20 August 1853, just as an angry mob of 500–600 miners went to assemble outside the government camp at Waranga, the authorities used a legal technicality to release some mining tax evaders.[32] A meeting in Beechworth called for reducing the licence fee to ten shillings and voting rights for the mining settlements.[32] A larger rally attended by 20,000 people was held at Hospital Hill in Bendigo on 23 August 1853, which resolved to support a mining tariff fixed at 10 shillings a month.[35][36]

There was a second multinational-style assembly at View Point on 27 August 1853. The next day a procession of miners passed by the government camp with the sounds of bands and shouting and fifty pistol rounds as an assembly of about 2,000 miners took place.[32] On 29 August 1853, assistant commissioner Robert William Rede at Jones Creek counselled that a peaceful, political solution could still be found. In Ballarat, miners offered to surround the guard tent to protect gold reserves amid rumours of a planned robbery.[32]

A sitting of the goldfields committee of the Legislative Council in Melbourne on 6 September 1853 heard from goldfields activists Dr William Carr, W Fraser and William Jones.[37] An Act for the Better Management of the Goldfields was passed, which, upon receiving royal assent on 1 December, reduced the licence fee to 40 shillings for every three months. The act featured increasing fines in the order of 5, 10 and 15 pounds for repeat offenders, with goldfields residents required to carry their permits, which had to be available for inspection at all times. This temporarily relieved tensions in the colony. In November, the select committee bill proposed a licence fee of 1 pound for one month, 2 pounds for three months, 3 for six months and 5 pounds for 12 months, along with extending the voting franchise and land rights to the miners. La Trobe amended the scheme by increasing the six-month licence to 4 pounds, with a fee of 8 pounds for 12 months.[38]

On 3 December 1853, a crowd of 2,000–3,000 attended an anti-licence rally at View Point. Then, on 31 December 1854, about 500 people gathered there to elect a so-called "Diggers Congress".[37]

Legislative Council calls for Commission of Inquiry

[edit]La Trobe decided to cancel the September 1853 mining tax collections. The Legislative Council supported a Commission of Inquiry into goldfields grievances. It also considered a proposal to abolish the licence fee in return for a royalty on the gold and a nominal charge for maintaining the police service.[39] In November, it was resolved by the Legislative Council that the licence fee be reinstated on a sliding scale of 1 pound per month, 2 pounds per three months, 4 pounds for six months, and 8 pounds for 12 months. License evasion was punishable by increasing fines of 5, 15 and 30 pounds, with serial offenders liable to be sentenced to imprisonment. Licence inspections, treated as a great sport and "carried out in the style of an English fox-hunt"[40] by mounted officials, known to the miners by the warning call "Traps" or "Joes", were henceforth able to take place at any time without notice.[41][42]

The latter sobriquet was a reference to La Trobe, whose proclamations posted around the goldfields were signed and sealed "Walter Joseph Latrobe".[43] Many of the police were former convicts from Tasmania. They would get a fifty per cent commission from all fines imposed on unlicensed miners and grog sellers. Plainclothes officers enforced prohibition, and those involved in the illegal sale of alcohol were initially handed 50-pound fines. Subsequent offences were punishable by months of hard labour. This led to the corrupt practice of police demanding blackmail of 5 pounds from repeat offenders.[41][44][45]

Miners were arrested for not carrying licences on their person, as they often left them in their tents due to the typically wet and dirty conditions in the mines, then subjected to such indignities as being chained to trees and logs overnight.[46] The impost was most felt by a greater number of miners, who were finding the mining tax untenable without any more significant gold discoveries.[44]

In March 1854, La Trobe sent a reform package to the Legislative Council, which was adopted and sent to London for the approval of the Imperial parliament. The voting franchise would be extended to all miners upon purchasing a 12-month permit.[47]

Hotham replaces La Trobe

[edit]La Trobe's successor as lieutenant-governor, Sir Charles Hotham, who took up his commission in Victoria on 22 June 1854.[48] He instructed Rede to introduce a strict enforcement system and conduct a weekly cycle of licence hunts, which it was hoped would cause the exodus to the goldfields to be reversed.[49] In August 1854, Hotham and his wife were received in Ballarat during a tour of the Victorian goldfields. In September, Hotham imposed more frequent twice-weekly licence hunts, with more than half of the prospectors on the goldfields remaining non-compliant with the regulations.[41][49]

The miners in Bendigo responded to the increase in the frequency of licence hunts with threats of armed rebellion.[50]

Tensions escalate

[edit]Murder of James Scobie and the burning of the Eureka hotel

[edit]

In October 1854, James Scobie was murdered outside the Eureka Hotel. Johannes Gregorius was prosecuted for the murder. A colonial inquest found no evidence of culpability by the Bentley Hotel owners for the fatal injuries amid allegations that Magistrate D'Ewes had a conflict of interest presiding over a case involving the prosecution of Bentley, said to be a friend and indebted business partner.[51][52]

Gregorius, a physically disabled servant who worked for Father Smyth of St Alipius chapel, had been in the past subjected to police brutality and false arrest for licence evasion, even though he was exempt from the requirement.[53] On 15 October, a mass meeting of predominantly Catholic miners took place on Bakery Hill in protest over the treatment of Gregorius. Two days later, responding to the acquittal, a meeting of approximately 10,000 men occurred near the Eureka Hotel in protest. The hotel was set alight as Rede was pelted with eggs. The available security forces were unable to restore order.[54][55]

On 21 October, Andrew McIntyre and Thomas Fletcher were arrested for the arson attack on the Eureka Hotel.[56] A third man, John Westerby, was also indicted. A committee meeting of miners on Bakery Hill agreed to indemnify the bail sureties for McIntyre and Fletcher. As a large mob approached the government camp, the two men were hurriedly released under their own recognisance.[56]

Around this time two reward notices were distributed around Ballarat. One offered a 500-pound reward for information leading to an arrest in the Scobie murder case. The other announced the reward for more information about the Bank of Victoria heist in Ballarat that was carried out by robbers wearing black crepe-paper masks, and which was increased from 500 to 1,600 pounds.[49][57] Rede received a miner's delegation on 23 October which had heard that the police officers involved in the arrest of Gregorius would be dismissed. Two days later, a meeting led by Timothy Hayes and John Manning heard reports from the deputies sent to negotiate with Rede. The meeting resolved to petition Hotham for a retrial of Gregorius and to the reassignment of the assistant commissioner Johnston away from Ballarat.[56]

On 27 October, Captain John Wellesley Thomas laid contingency plans for the defence of the government outpost. In the weeks leading up to the battle, men had already been aiming musket balls at the barely fortified barracks during the night.[58] On 30 October, Hotham appointed a board of enquiry into the murder of James Scobie to sit in Ballarat on 2 and 10 November. The panel included Melbourne magistrate Evelyn Sturt, assisted by his local magistrate Charles Hackett and William McCrea. After receiving representations from the US consul, Hotham released James Tarleton from custody.[59]

The inquiry into the Ballarat rioting concluded with a statement made on 10 November in the name of the Ballarat Reform League that was signed by John Basson Humffray, Fredrick Vern, Henry Ross and Samuel Irwin of the Geelong Advertiser. The final report agreed with the League's submission, blaming the government camp for the unsatisfactory state of affairs. The recommendation that Magistrate Dewes and Sergeant Major-Milne of the constabulary should be dismissed was acted upon.[56]

On 1 November, around 5,000 miners gathered in Bendigo, as a plan was drawn up to organise the diggers at all the mining settlements, with speakers openly advocating physical force addressing the crowd.[60]

Ballarat Reform League meetings

[edit]

On 11 November 1854, a crowd of more than 10,000 gathered at Bakery Hill, directly opposite the government encampment. At this meeting, the Ballarat Reform League was formally established under the chairmanship of Chartist John Humffray. (Several other reform league leaders, including George Black, Henry Holyoake, and Tom Kennedy, are also believed to have been Chartists.)[61] It was reported by the Ballarat Times that at the appointed hour, the "Union Jack and the American ensign were hoisted as signals for the people to assemble".[62] It was at this time the Union Jack became a national flag while being "inscribed with slogans as a protest flag of the Chartist movement in the nineteenth century".[63]

The Ballarat Reform League charter was inspired by the charter ratified at the 1839 Chartist National Convention held in London. The Ballarat charter contains five of the same demands as the London one: A full and fair representation, Manhood suffrage, No property qualification of members for the Legislative Council, Payment of members of parliament.[64][65][66] The Ballarat league did not adopt the Chartist's sixth demand: secret ballots. The meeting passed a resolution "that it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called on to obey, that taxation without representation is tyranny". The meeting resolved to secede from the United Kingdom if the situation did not improve.[67]

Throughout the following weeks, the league sought to negotiate with Rede and Hotham on the specific matters relating to Bentley and the death of James Scobie, the men being tried for the burning of the Eureka Hotel, the broader issues of the abolition of the licence, suffrage and democratic representation of the goldfields, and the disbanding of the gold commission.[56]

Hotham sent a message to England on 16 November which revealed his intention to establish an inquiry into goldfields grievances. Notes to the royal commissioners had already been made on 6 November, where Hotham stated his opposition to an export duty on gold replacing the universal mining tax. W. C. Haines MLC was to be the chairman, serving alongside lawmakers John Fawkner, John O'Shanassy, William Westgarth, as well as chief gold commissioner William Wright.[68] These men were likely to be sympathetic to the diggers.[69]

Rather than hear the Ballarat Reform League's grievances, Rede increased the police presence on the Ballarat goldfields and summoned reinforcements from Melbourne.[70] Rede told one deputation that their campaign against "The licence is a mere cloak to cover a democratic revolution",[71] and the day before the battle reported to the chief gold commissioner that the government forces stood ready to "crush them and the democratic agitation at one blow".[72]

The James Scobie murder trial ended on 18 November 1854, with the accused, James Bentley, Thomas Farrell and William Hance, being convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to three years of hard labour on a road crew.[73] Catherine Bentley was acquitted. Two days later, the miners Westerby, Fletcher and McIntyre were convicted for burning the Eureka Hotel and were sentenced to jail terms of six, four and three months.[73]

The jury recommended the prerogative of mercy be evoked and noted that they held the local authorities in Ballarat responsible for the loss of property. One week later, a reform league delegation, including Humffray, met with Hotham, Stawell and Foster to negotiate the release of the three Eureka Hotel rioters. Hotham declared that he would take a stand on the word "demand", satisfied that due process had been observed.[74] Father Smyth informed Rede in confidence that he believed the miners might be about to march on the government outpost.[56]

Escalating violence as military convoy looted

[edit]Foot police reinforcements arrived in Ballarat on 19 October 1854. A further detachment of the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot arrived a few days behind. On 28 November, the 12th (East Suffolk) Regiment of Foot arrived to reinforce the government camp in Ballarat. As they moved alongside where the Eureka Stockade was about to be erected, members of the convoy were attacked by a mob looking to loot the wagons.[75]

By the beginning of December, the police contingent at Ballarat had been surpassed by the number of soldiers from the 12th and 40th regiments.[76] The strength of the various units in the government camp was: 40th regiment (infantry): 87 men; 40th regiment (mounted): 30 men; 12th regiment (infantry): 65 men; mounted police: 70 men; and the foot police: 24 men.[77]

Open rebellion

[edit]Paramilitary mobilisation and swearing allegiance to the Southern Cross

[edit]

On 29 November, a meeting that drew a crowd of around 10,000 was held at Bakery Hill. The miners heard from their deputies news of the unsuccessful outcome of their meeting with Hotham, demanding the release of Westerby, Fletcher and McIntyre.

The Eureka Flag was flown there for the first time.[78][note 1] The crowd was incited by Timothy Hayes shouting, "Are you ready to die?" and Fredrick Vern, who was accused of abandoning the garrison four days later as soon as the danger arrived, with suspicions of being a double agent.[80][81][82]

Rede responded by ordering police to conduct a licence search on 30 November. There was further rioting where objects were thrown at military and law enforcement by the protesting miners who had refused to cooperate with licence inspections en masse.[83] Eight licence defaulters were arrested. Most of the military resources available had to be summoned to extricate the arresting officers from the angry mob that had assembled.[84]

There was another gathering on Bakery Hill where a militant leader, Peter Lalor, mounted a stump armed with a rifle and proclaimed "liberty". He then called for volunteers to step forward and be sworn into companies, and rebel captains to be appointed.[85][note 2]

Lalor knelt, pointed to the Eureka Flag, and swore to the affirmation of his fellow demonstrators: "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties".[87]

In a dispatch dated 20 December 1854, Hotham reported: "The disaffected miners ... held a meeting whereat the Australian flag of independence was solemnly consecrated and vows offered for its defence".[88]

Fortification of the Eureka lead

[edit]

After the oath swearing ceremony, about 1,000 rebels marched in double file from Bakery Hill to the Eureka lead behind the Eureka Flag being carried by Henry Ross, where construction of the stockade took place between 30 November and 2 December.[89][90] There were existing mines within the stockade.[91] The stockade consisted of diagonal wooden spikes made from materials including pit props and overturned horse carts. It encompassed an area said to be one acre. Other estimates give the dimensions of the stockade as 100 feet (30 m) x 200 feet (61 m).[92] Contemporaneous descriptions and representations vary and have the stockade as either rectangular or semi-circular.[93]

Lalor later said the stockade "was nothing more than an enclosure to keep our own men together, and was never erected with an eye to military defence".[94] Peter FitzSimons asserts that Lalor may have downplayed the fact that the Eureka Stockade was intended as something of a fortress at a time when "it was very much in his interests" to do so.[95] The construction work was overseen by Vern, who had apparently received instruction in military methods. John Lynch wrote that his "military learning comprehended the whole system of warfare ... fortification was his strong point".[96]

Other descriptions of the stockade contradicted Lalor's recollection of it being a simple fence after the fall of the stockade.[97] Testimony was heard at the high treason trials for the Eureka rebels that the stockade was four to seven feet high in places and was unable to be negotiated on horseback without being reduced.[98]

Hotham feared that the "network of rabbit burrows" on the goldfields would prove readily defensible as his forces "on the rough pot-holed ground would be unable to advance in regular formation and would be picked off easily by snipers". These considerations were part of the reasoning behind the decision to move into position in the early morning for a surprise attack.[99] Carboni details the rebel dispositions:

The shepherds' holes inside the lower part of the stockade had been turned into rifle-pits, and were now occupied by Californians of the I. C. Rangers' Brigade, some twenty or thirty in all, who had kept watch at the 'outposts' during the night.[100]

The location of the stockade has been described as "appalling from a defensive point of view", as it was situated on "a gentle slope, which exposed a sizeable portion of its interior to fire from nearby high ground".[101] A detachment of 800 men, which included "two field pieces and two howitzers" was under the commander in chief of the British forces in Australia, Major General Sir Robert Nickle. Nickle himself, who had seen action during the 1798 Irish rebellion, arrived after the insurgency had been put down.[102][103] In 1860, Withers stated in a lecture that "The site was most injudicious for any purpose of defence as it was easily commanded from adjacent spots, and the ease with which the place could be taken was apparent to the most unprofessional eye".[104]

At 4 am on the morning of 1 December, the rebels were observed to be massing on Bakery Hill, but a government raiding party found the area vacated. Again, Rede ordered the riot act read to a mob that had gathered around Bath's Hotel, with mounted police breaking up the unlawful assembly. Raffaello Carboni, George Black and Father Smyth met with Rede to present a peace proposal. Rede was suspicious of the Chartist undercurrent of the anti-mining tax movement and he rejected the proposals.[105]

The rebels sent out scouts and established picket lines in order to have advance warning of Rede's movements and a request for reinforcements to the other mining settlements.[106] The "moral force" faction had withdrawn from the protest movement as the men of violence moved into the ascendancy. The rebels continued to fortify their position as 300-400 men arrived from Creswick's Creek, and Carboni recalls they were: "dirty and ragged, and proved the greatest nuisance. One of them, Michael Tuohy, behaved valiantly".[107] Once foraging parties were organised, there was a rebel garrison of around 200 men. Amid the Saturday night revelry, low munitions, and major desertions, Lalor ordered that any man attempting to leave the stockade be shot.[108]

Vinegar Hill blunder: Irish dimension factors in dwindling numbers at stockade

[edit]

The Argus newspaper of 4 December 1854 reported that the Union Jack "had" to be hoisted underneath the Eureka Flag at the stockade and that both flags were in possession of the foot police.[109] Peter FitzSimons has questioned whether this contemporaneous report of the otherwise unaccounted-for Union Jack known as the Eureka Jack being present is accurate.[110] Among those willing to credit the first report of the battle as being true and correct it has been theorised that the hoisting of a Union Jack at the stockade was possibly an 11th-hour response to the divided loyalties among the heterogeneous rebel force which was in the process of dissipating.[111]

At one point up to 1,500 of 17,280 men in Ballarat were garrisoning the stockade, with as few as 120 taking part in the battle.[112][113][114] Lalor's choice of password for the night of 2 December—"Vinegar Hill"[115][116][117]—caused support for the rebellion to fall away among those who were otherwise disposed to resist the military, as word spread that the question of Irish home rule had become involved. One survivor of the battle stated that "the collapse of the rising at Ballarat may be regarded as mainly attributable to the password given by Lalor on the night before the assault". Asked by one of his subordinates for the "night pass", he gave "Vinegar Hill", the site of a battle during the 1798 Irish rebellion. The 1804 Castle Hill uprising, also known as the second battle of Vinegar Hill, was the site of a convict rebellion in the colony of New South Wales, involving mainly Irish transportees, some of whom were at Vinegar Hill.[118]

William Craig recalled that "Many at Ballaarat, who were disposed before that to resist the military, now quietly withdrew from the movement".[119] In his memoirs, Lynch states: "On the afternoon of Saturday we had a force of seven hundred men on whom we thought we could rely". There was a false alarm from the picket line during the night. The subsequent roll call revealed there had been a sizable desertion that Lynch says "ought to have been seriously considered, but it was not".[120]

There were rebellious miners converging on Ballarat from Bendigo, Forrest Creek, and Creswick to take part in the armed struggle. The latter contingent was said to number a thousand men, "but when the news circulated that Irish independence had crept into the movement, almost all turned back".[119] FitzSimons points out that although the number of reinforcements converging on Ballarat was probably closer to 500, there is no doubt that as a result of the choice of password "the Stockade is denied many strong-armed men because of the feeling that the Irish have taken over".[121] Withers states that:

Lalor, it is said, gave 'Vinegar Hill' as the night's pass-word, but neither he nor his adherents expected that the fatal action of Sunday was coming, and some of his followers, incited by the sinister omen of the pass-word, abandoned that night what they saw was a badly organised and not very hopeful movement.[117]

It is certain that Irish-born people were strongly represented at the Eureka Stockade.[118] Most of the rebels inside the stockade at the time of the battle were Irish, and the area where the defensive position was established was overwhelmingly populated by Irish miners.[note 3] Blainey has advanced the view that the white cross of the Eureka Flag is "really an Irish cross rather than being [a] configuration of the Southern Cross".[126]

There is another theory advanced by Gregory Blake, military historian and author of Eureka Stockade: A Ferocious and Bloody Battle, who concedes that two flags may have been flown on the day of the battle, as the miners were claiming to be defending their British rights.[127]

In a signed contemporaneous affidavit dated 7 December 1854, Private Hugh King, who was at the battle serving with the 40th regiment, recalled that:

... three or four hundred yards a heavy fire from the stockade was opened on the troops and me. When the fire was opened on us we received orders to fire. I saw some of the 40th wounded lying on the ground but I cannot say that it was before the fire on both sides. I think some of the men in the stockade should-they had a flag flying in the stockade; it was a white cross of five stars on a blue ground. – flag was afterwards taken from one of the prisoners like a union jack – we fired and advanced on the stockade, when we jumped over, we were ordered to take all we could prisoners ...[128]

There was a further report in The Argus, 9 December 1854 edition, stating that Hugh King had given live testimony at the committal hearings for the Eureka rebels where he stated that the flag was found:

... rollen up in the breast of a[n] [unidentified] prisoner. He [King] advanced with the rest, firing as they advanced ... several shots were fired on them after they entered [the stockade]. He observed the prisoner [Hayes] brought down from a tent in custody.[129]

Blake leaves open the possibility that the flag being carried by the prisoner had been souvenired from the flag pole as the routed garrison was fleeing the stockade.[130][127][note 4]

Departing detachment of Independent Californian Rangers leaves small garrison behind

[edit]Amid the rising number of rebels absent without leave throughout 2 December, a contingent of 200 Americans under James McGill arrived at 4 pm. Styled as "The Independent Californian Rangers' Revolver Brigade", they had horses and were equipped with sidearms and Mexican knives. In a fateful decision, McGill took most of his two hundred Californian Rangers away from the stockade to intercept rumoured British reinforcements from Melbourne. Many Saturday night revellers within the rebel garrison returned to their own tents, assuming that the government camp would not attack on the Sabbath day. A small contingent of miners remained at the stockade overnight, which the spies reported to Rede. Common estimates for the size of the garrison at the time of the attack on 3 December range from 120 to 150 men.[94][133][134]

According to Lalor's reckoning: "There were about 70 men possessing guns, 30 with pikes and 30 with pistols, but many had no more than one or two rounds of ammunition. Their coolness and bravery were admirable when it is considered that the odds were 3 to 1 against".[135] Lalor's command was riddled with informants, and Rede was kept well advised of his movements, particularly through the work of government agents Henry Goodenough and Andrew Peters, who were embedded within the rebel garrison.[136][137]

Initially outnumbering the government camp considerably, Lalor had already devised a strategy where "if the government forces come to attack us, we should meet them on the Gravel Pits, and if compelled, we should retreat by the heights to the old Canadian Gully, and there we shall make our final stand".[138] On being brought to battle that day, Lalor stated: "we would have retreated, but it was then too late".[135]

On the eve of the battle, Father Smyth issued a plea for Catholics to down their arms and attend mass the following day.[139]

Battle of the Eureka Stockade

[edit]

Rede planned to send the combined military police formation of 276 men under the command of Captain Thomas to attack the Eureka Stockade when the rebel garrison was observed to be at a low watermark. The police and military had the element of surprise and timed their assault on the stockade for dawn on Sunday, the Christian Sabbath day of rest. The soldiers and police marched off in silence at around 3:30 am Sunday morning after the troopers had drunk the traditional tot of rum.[140]

The British commander used bugle calls to coordinate his forces. The 40th regiment provided covering fire from one end, with mounted police covering the flanks. Enemy contact began at approximately 150 yards as the two columns of regular infantry and the contingent of foot police moved into position.[141] Although Lalor claimed that the government forces fired the first shot, it appears from all the other remaining accounts as if it came from the rebel garrison.[142]

According to Gregory Blake, the fighting in Ballarat on 3 December 1854 was not one-sided and full of indiscriminate murder by the colonial forces. In his memoirs, one of Lalor's captains, John Lynch, mentions "some sharp shooting".[143] For at least 10 minutes, the rebels offered stiff resistance, with ranged fire coming from the Eureka Stockade garrison such that Thomas's best formation, the 40th regiment, wavered and had to be rallied. Blake says this is "stark evidence of the effectiveness of the defender's fire".[144]

Eventually, the rebels started to run short of ammunition, and the government advance resumed. The Victorian police contingent led the way over the top as the forlorn hope in a bayonet charge. Lalor had his arm shattered by a musket ball and was secreted away by supporters, with his arm later requiring amputation. The Eureka flag was captured by Constable John King, who volunteered to scale the flagpole, which then snapped. The exact number of casualties cannot be determined. After the battle, the registrar of Ballarat entered the names of 27 people into the Victorian death register. Lalor lists 34 rebel casualties, of which 22 died.[145] In his report, Captain Thomas states that one soldier was killed in action, two died of wounds, and fourteen were wounded.[141]

Aftermath

[edit]Blainey has commented that "Every government in the world would probably have counter-attacked in the face of the building of the stockade".[146] Hotham would receive the news that the government forces had been victorious the same day, with Stawell waiting outside Saint James church, where Hotham was attending a service with Foster. He immediately set about firing up the government printing press to put out placards calling for support from among the colonists.[147]

A state of martial law was proclaimed with no lights allowed in any tent after 8 pm "even though the legal basis for it was dubious".[148][149][150] It was around this time that a number of unprovoked shots were fired from the government camp toward the diggings.[151] Unrelated first-hand accounts variously state that a woman, her infant child and several men were killed or wounded in an episode of indiscriminate shooting.[note 5]

News of the battle spread quickly to Melbourne and across the goldfields, turning a perceived government military victory in repressing a minor insurrection into a public relations disaster. On 5 December, reinforcements under Major General Nickle arrived at the government camp in Ballarat. Reverend Taylor expected further repression, stating that:

4 Dec. Quiet reigned through the day. Evening thrown into alarm by a volley of musketry fired by the sentries. The cause, it appears, was the firing into the camps by some one unknown...... 5 Dec. Martial Law proclaimed, Major-General Sir Robert Nickle arrived with a force of 1000 soldiers. The Reign of Terror commences.[154]

As it happened, Nickle proved to be a wise, considered and even-handed military commander who calmed the tensions and Taylor "found him to be a very affable and kind gentleman".[155][154] Evans' diary records the effect of his conduct as follows:

Sir Robert Nichol [sic] has taken the reins of power at the Camp. Already there is a sensible and gratifying deference in its appearance. The old General went round unattended to several tents early this morning & made enquiries from the diggers relative to the cause of the outbreak. It is very probable from the humane & temperate course he is taking that he will establish himself in the goodwill of the people.[156]

The same day several thousand people attended a public meeting held in Swanston Street, Melbourne. There were howls of anger when several pro-government motions were proposed. When the seconder of one motion, which called for the maintenance of law and order, framed the issue as "would they support the flag of old England...or the new flag of the Southern Cross", the speaker was drowned out by groans from the crowd. In response, it was then proposed that restoring order required removing the government that caused the disorder in the first place. Amid cheers from the crowd, the mayor of Melbourne as chairman declared the pro-government motions carried and hastily adjourned the meeting. However, a new chairman was elected, and motions condemning the government and calling for the resignation of Foster were passed.[157][158]

Foster had acted as the temporary administrator of Victoria during the transition from La Trobe to Hotham. As colonial secretary to the lieutenant governor, he rigorously enforced the mining licence requirement amid the colony's budget and labour crisis. Foster had already offered his resignation on 4 December as the protests began, which Hotham accepted a week later.[159]

On 6 December 1854, a 6,000-strong crowd gathered at Saint Paul's Cathedral protesting against the government's response to the Eureka Rebellion,[160] as a group of 13 rebel prisoners were indicted for treason. Newspapers in the colony characterised it as a brutal overuse of force, in a situation brought about by the actions of government officials, and public condemnation became insurmountable.[161] Letters Patent formally appointing the members of the Royal Commission were signed and sealed on 7 December 1854.[162]

Hotham managed to have an auxiliary force of 1,500 special constables from Melbourne sworn in along with others from Geelong, with his resolve that further "rioting and sedition would be speedily put down", undeterred by the rebuff his policies had received from the general public. In Ballarat, only one man stepped forward and answered the call to enlist.[163] By the beginning of 1855, normalcy had returned to the streets of Ballarat, with mounted patrols no longer being a feature of daily life.[164]

Among the government officials, although Foster was made a scapegoat for the affair at Eureka, he remained a member of the Legislative Council. He briefly served on the parliamentary executive as treasurer before returning to England in 1857, where he published his speeches on the Eureka Rebellion.[159] Rede was recalled from Ballarat and kept on full pay until 1855. He served as the sheriff at Geelong (1857), Ballarat (1868), and Melbourne (1877) and was the Commandant of the Volunteer Rifles, being the second-in-command at Port Phillip.[165]

In 1880, Rede was sheriff at the trial of Ned Kelly and an official witness to his execution.[165] Hotham was promoted on 22 May 1855 when the title of the colony's chief executive was changed from lieutenant governor to governor. He died in Melbourne on New Year's Eve 1855 while in a coma after suffering from a severe cold.[166]

Trials for sedition and high treason

[edit]

The first trial relating to the rebellion was a charge of sedition against Henry Seekamp of the Ballarat Times. Seekamp was tried and convicted of seditious libel by a Melbourne jury on 23 January 1855 and, after a series of appeals, sentenced to six months imprisonment on 23 March. He was released from prison on 28 June 1855, three months early. During Seekamp's absence, Clara served as editor of the Ballarat Times.[167]

Of the approximately 120 individuals detained after the battle, thirteen were put on trial for high treason. There were Timothy Hayes, Raffaello Carboni, John Manning, John Joseph, Jan Vennick, James Beattie, Henry Reid, Michael Tuohy, James Macfie Campbell, William Molloy, Jacob Sorenson, Thomas Dignum, and John Phelan.

The African American John Joseph was the first rebel put on trial. Matters of fact were decided by a lay juries drawn from a general public that was largely sympathetic to the rebel cause. One of the junior counsels for Joseph was Butler Cole Aspinall, who appeared pro bono. Formerly chief of parliamentary reporting for The Argus before returning to practice, he was elected to the Legislative Assembly in the wake of the Eureka trials. He received many other criminal briefs later in his legal career, including that of Henry James O'Farrell, who was indicted for an 1868 assassination attempt on the Duke of Edinburgh in Sydney. Gavan Duffy said of Aspinall that he was: "one of the half-dozen men whose undoubted genius gave the Parliament of Victoria a first place among colonial legislatures".[168]

The jury's verdict of not guilty was greeted by applause, with two men being sentenced to a week in prison for contempt of court.[169] Over 10,000 people had come to hear the jury's verdict. Joseph was carried around the streets of Melbourne in a chair in triumph, according to The Ballarat Star.[170]

Manning's case was heard next. The indicted rebels were acquitted in quick succession, with the last five all being tried together on 27 March. The lead defence counsel Archibald Michie observed that the proceedings had become "weary, stale, flat, dull and unprofitable".[171][172] The trials have, on several occasions, been described as a farce.[173]

As Molony points out, the legality of putting a foreign national on trial for treason had been settled as far back as 1649. A difficulty the Crown prosecutor faced regarding the mens rea was that:

... it was another thing entirely to prove that any treasonable intent was harboured in the mind of John Joseph.... These matters were weighty and more conclusive of proof than a charge of murder, but they left the Crown with an arduous task of convincing the jury that Joseph had acted with such an elevated intent.[174]

The Colonial Secretary Lord John Russell rebuked Hotham over the decision to prosecute the captured rebels, saying in a despatch:

... respecting the trial of the prisoners taken at Ballarat, I wish to say that, although I do not doubt you have acted to the best of your judgment, and under advice, yet I question the expediency of bringing these rioters to trial under a charge of High Treason, being one so difficult of proof, and so open to objections of the kind which appear to have prevailed with the jury.[175]

Commission of Inquiry report

[edit]On 14 December 1854, the goldfields commission sat for the first time. The first Ballarat session was held four days later at Bath's Hotel.[176] In a meeting with Hotham on 8 January 1855, the goldfields commissioners made an interim recommendation that the mining tax be scrapped, and two days later made a submission advising a general amnesty be granted for all those rebels on the run from the Eureka Stockade.[177]

The commission's final report into the Victorian goldfields was presented to Hotham on 27 March 1855. It was scathing in its assessment of the administration of the goldfields, particularly the Eureka Stockade affair. Within 12 months, all but one of the demands of the Ballarat Reform League were implemented. The changes included the abolition of gold licences to be replaced with an export duty. An annual 1-pound miner's right that entitles the holder to voting rights for the lower house and a land deed was introduced. Mining wardens replaced the gold commissioners, and there was a reduction in police numbers. The Legislative Council was reconstituted to provide representation for the major gold field settlements.[178]

Concerning the tensions caused by the Chinese presence on the goldfields, the report states inter alia:

A most serious social question with reference to the gold-fields, and one that has lately crept on with rapid but almost unobserved steps, is with reference to the great number of the Chinese. This number, although already almost incredible, yet appears to be still fast increasing ... The question of the influx of such large numbers of a pagan and inferior race is a very serious one ... The statement of one of this people, that "all" were coming, comprises an unpleasant possibility of the future, that a comparative handful of colonists may be buried in a countless throng of Chinamen ... some step is here necessary, if not to prohibit, at least to check and diminish this influx.[179]

The legislative remedy came in the form of a poll tax, assented to on 12 June 1855, made payable by Chinese immigrants.[180]

Humffray commended the report in a letter to the editor, saying:

The [commission] report is a most masterly and statesmanlike document, and if its wise suggestions are wisely and honestly carried out, that commission will have rendered a service to the colony ... the wrongs and grievances of the digging community are clearly set forth in the Report, and practical schemes suggested for their removal.[181]

Peter Lalor enters parliament

[edit]

Lalor, in his letter to the colonists of Victoria, lamented that:

There are two things connected with the late outbreak (Eureka) which I deeply regret. The first is, that we shouldn't have been forced to take up arms at all; and the second is, that when we were compelled to take the field in our own defence, we were unable (through want of arms, ammunition and a little organisation) to inflict on the real authors of the outbreak the punishment they so richly deserved.[142]

In July 1855, the Victorian Constitution received royal assent, which provided for a fully elected bicameral parliament, with a new Legislative Assembly of 60 seats and a reformed Legislative Council of 30 seats.[182] The franchise was available to all holders of the miner's right for the inaugural Legislative Assembly election, with members of parliament themselves subject to property qualifications. In the interim, five representatives from the mining settlements were appointed to the old part elected Legislative Council, including Lalor and Hummfray in Ballarat.[183]

Lalor is said to have "aroused hostility among his digger constituents" by not supporting the principle of one vote, one value. He instead preferred the existing property-based franchise and plural voting, where ownership of a certain number of holdings conferred the right to cast multiple ballots. In the event when the Electoral Act of 1856 (Vic) was enacted, these provisions were not carried forward. Universal adult male suffrage was then introduced in 1857 for Legislative Assembly elections.[85][184][185] (That said, property and later ratepaying franchises and hence 'plural voting' for some persisted: one-person-one-vote was not achieved until 1938 and property qualifications remained until 1950 for the Legislative Council.[186])

On another occasion, there were 17,745 signatures from Ballarat residents on a petition against a regressive land ownership bill Lalor supported that favoured the "squattocracy", who came from pioneering families who had acquired their prime agricultural land through occupation and were not of a mind to give up their monopoly on the countryside, nor political representation. He is on record as having been opposed to payment for members of the Legislative Council, which had been another key demand of the Ballarat Reform League. In November 1855, under the new constitutional arrangements, Lalor was elected unopposed to the Legislative Assembly for the seat of North Grenville, which he held from 1856 to 1859.[85][184][185]

Withers and others have noted that those who considered Lalor a legendary folk hero were surprised that he was more concerned with accumulating styles and estates than securing any gains from the Eureka Rebellion.[187][188] Lalor was found wanting by a critical mass of his supporters, who had hitherto sustained his political career. Lynch recalls that:

The semi-Chartist, revolutionary Chief, the radical reformer thus suddenly metamorphosed into a smug Tory, was surely a spectacle to make good men weep. But good men did more than weep; they decried him with vehemence in keeping with the recoil of their sentiments".[120][note 6]

Under pressure from constituents to clarify his position, in a letter dated 1 January 1857 published in the Ballarat Star, Lalor described his political ideology in the following terms:

I would ask the gentlemen what they mean by the term 'Democracy'? Do they mean Chartism, or Communism, or Republicanism? If so, I never was, I am not now, nor do I ever intend to be a democrat. But if democracy means opposition to a tyrannical press, a tyrannical people, or a tyrannical government, then I have ever been, am still, and I ever will remain a democrat.[190]

From there on, he never represented a Ballarat-based constituency again. He successfully contested the Melbourne seat of South Grant in the Legislative Assembly in 1859, until being twice defeated at the polls in 1871, on the second occasion contesting the seat of North Melbourne. In 1874, he was again elected as the member for South Grant, which he represented in parliament until he died in 1889.

Lalor served as chairman of committees from 1859 to 1868 before being sworn into the ministry. He was first appointed as Commissioner of Trade and Customs in 1875, an office he held throughout 1877-1880, riding the fortunes of his parliamentary faction. He was briefly Postmaster-General of Victoria from May to July 1877. Lalor served as the speaker from 1880 and 1887. When his health situation forced him to step down, parliament awarded him a sum of 4,000 pounds.[191][192] Lalor twice refused to accept the highest Imperial honour of a British knighthood.[193][194]

Location of Bakery Hill and the Eureka Stockade

[edit]In 1931, R. S. Reed claimed that "an old tree stump on the south side of Victoria Street, near Humffray Street, is the historic tree at which the pioneer diggers gathered in the days before the Eureka Stockade to discuss their grievances against the officialdom of the time".[195] Reed called for the formation of a committee of citizens to "beautify the spot, and to preserve the tree stump" upon which Lalor addressed the assembled rebels during the oath swearing ceremony.[195] It was also reported the stump "has been securely fenced in, and the enclosed area is to be planted with floriferous trees. The spot is adjacent to Eureka, which is famed alike for the stockade fight and for the fact that the Welcome Nugget. (sold for £10,500) was discovered in 1858 within a stone's throw of it".[196]

A 2015 report commissioned by the City of Ballarat found that given documentary evidence and its elevation, the most likely location of the oath swearing ceremony is 29 St. Paul's Way, Bakery Hill.[197] As of 2016, the area was a car park awaiting residential development.[198]

As the materials used by the rebels to fortify the Eureka lead were quickly removed and the landscape altered by mining, the exact location of the Eureka Stockade is unknown.[199] Various studies have been undertaken that have arrived at different conclusions. In 1994, Jack Harvey conducted an exhaustive survey and concluded that the Eureka Stockade Memorial is situated within the confines of the historical Eureka Stockade.[200][201]

Political legacy

[edit]The actual political significance of the Eureka Rebellion is contested. It has been variously interpreted as a revolt of free men against imperial tyranny, of independent free enterprise against burdensome taxation, of labour against a privileged ruling class, or as an expression of republicanism. Some historians believe that the prominence of the event in the public record has come about because Australian history does not include a major armed rebellion phase equivalent to the French Revolution, the English Civil War, or the Indian Rebellion, making the Eureka story inflated well beyond its real importance. Others maintain that Eureka was a seminal event and that it marked a major change in the course of Australian history.[126]

In modern times, there have been calls for the official Australian national flag to be replaced by the Eureka Flag.[202][203]

In his eyewitness account, Carboni stated that "amongst the foreigners ... there was no democratic feeling, but merely a spirit of resistance to the licence fee". He also disputes the accusations "that have branded the miners of Ballarat as disloyal to their QUEEN".[204]

American author Mark Twain, who journeyed to Ballarat, noted how the Eureka Rebellion was well remembered by locals, likening it to the battles of Concord and Battle of Lexington in his 1897 travel book Following the Equator. Concerning the legacy of the battle, he stated:

I think it may be called the finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution - small in size; but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for a principle, a stand against injustice and oppression.... It is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle.[205]

H. V. Evatt, leader of the ALP, wrote that "Australian democracy was born at Eureka". Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies said, "the Eureka revolution was an earnest attempt at democratic government". Ben Chifley, former ALP Prime Minister, believed the Eureka Rebellion was not just a "short-lived revolt against tyrannical authority" and expressed the view that it was consequential in terms of Australia's development as a nation in that "it was the first real affirmation of our determination to be masters of our own political destiny".[4]

Blainey has described Evatt's view as "slightly inflammatory"[126] for such reasons as the first parliamentary elections in Australian history actually took place in South Australia, albeit according to a more limited property-based franchise, observing that it had been a battle cry for nationalists, republicans, liberals, radicals, and communists with "each creed finding in the rebellion the lessons they liked to see". He acknowledged that the inaugural parliament that convened under Victoria's revised constitution "was alert to the democratic spirit of the goldfields". The parliament eventually passed laws that enabled all adult males to vote by secret ballot and contest Legislative Assembly elections.[5][note 7] He points out that many miners were temporary migrants from Britain and the United States who did not intend to settle permanently in Australia, saying:

Nowadays it is common to see the noble Eureka Flag and the rebellion of 1854 as the symbol of Australian independence, of freedom from foreign domination; but many saw the rebellion in 1854 as an uprising by outsiders who were exploiting the country's resources and refusing to pay their fair share of taxes. So we make history do its handsprings.[14]

In 1999, the Premier of New South Wales, Bob Carr, dismissed the Eureka Stockade as a "protest without consequence".[209] Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson made the Eureka Flag a federal election campaign issue in 2004 saying "I think people have tried to make too much of the Eureka Stockade ... trying to give it a credibility and standing that it probably doesn't enjoy".[210] In the opening address of the Eureka 150 Democracy Conference in 2004, the Premier of Victoria, Steve Bracks, said "that Eureka was about the struggle for basic democratic rights. It was not about a riot—it was about rights".[211]

Commemoration

[edit]

19th century

[edit]Following an earlier meeting on 22 November 1855 held at the location of the stockade where calls for compensation were made, Carboni returned to the rebel burial ground for the first anniversary of the battle and remained for the day selling copies of his self-published memoirs. In 1856, for the second anniversary, veteran John Lynch gave a speech as several hundred people gathered at the Eureka lead before a march to the local cemetery to remember the fall of the Eureka Stockade. There was a collection to building railings around the Eureka burial ground.[214][215][216]

On 22 March 1856, a diggers' memorial was erected in the Ballaarat Old Cemetery near marked graves. Sculpted in stone from the Barrabool Hills by James Leggatt in Geelong, it features a pillar with the names of the deceased miners and the inscription "Sacred to the memory of those who fell on the memorable 3 December 1854 in resisting the unconstitutional proceedings of the Victorian Government".[217]

In 1857, the anniversary was much more low-key and was marked by "some of the friends of those who fell to decorate their tombs with flowers ... the occasion will be passed over without any public demonstrations...". In 1858, at the appointed time, there was only a crowd of seven people at the cemetery, two of whom were journalists. The Ballarat Star report "deplored the general lack of interest and neglected condition of the graves".[214][215][216]

The soldiers were buried in the same cemetery as the rebels. In August 1872, the area surrounding the soldiers' graves was enclosed with a fence. A soldiers' memorial was constructed in 1879, an obelisk constructed of limestone sourced from Waurn Ponds with the words "Victoria" and "Duty" carved in its north and south faces, respectively.[218][219]

In the 1860s and 1870s, press interest in the events that had taken place at the Eureka Stockade dwindled, with the anniversary rating the occasional reference in the Courier and Star. Eureka was kept alive at the campfires, pubs, and at memorial events in Ballarat. Key living figures such as Lalor and Humffray were still in the public eye.[216]

The Eureka Stockade Monument located within the Eureka Stockade Gardens dates from 1884 and has been added to the Australian National Heritage List.[220] A meeting was held at the partially completed monument on 3 December 1884. It appears there were no further gatherings at the Eureka Stockade Monument until the 50th-anniversary commemorations in 1904.[221]

For at least ten years, beginning in 1884, the Old Colonists' Association held a service on or around the anniversary at Ballarat's Eastern Oval in conjunction with its annual charity appeal. There was some reference made to the Eureka Stockade. It was sometimes preceded by a march from the Old Colonists' Hall in Lydiard Street.[222]

Some of the earliest recorded examples of the Eureka Flag being used as a symbol of white nationalism and trade unionism are from the late 19th century. According to an oral tradition, the Eureka Flag was displayed at a seaman's union protest against using cheap Asian labour on ships at Circular Quay in 1878.[223] In August 1890, the Eureka Flag was draped from a platform in front of a crowd of 30,000 protesters assembled at the Yarra Bank in Melbourne in a show of solidarity with maritime workers.[224][225][226] There was a similar flag flown prominently above the camp at Barcaldine during the 1891 Australian shearers' strike.[227]

In 1889, Melbourne businessmen employed renowned American cyclorama artist Thaddeus Welch, who teamed up with local artist Izett Watson to paint a 1,000-square-foot (93 m2) canvas of the Eureka Stockade, wrapped around a wooden structure. When it opened in Melbourne, the exhibition was an instant hit. The Age reported in 1891 that "it afforded a very good opportunity for people to see what it might have been like at Eureka". The Australasian stated, "that many persons familiar with the incidents depicted, were able to testify to the fidelity of the painted scene". The people of Melbourne flocked to the cyclorama, paid up and had their picture taken before it. Eventually, it was dismantled and disappeared from sight.[212]

20th century

[edit]

For the 50th anniversary in 1904, around sixty veterans gathered for a reunion at the Eureka Stockade memorial with large crowds in attendance.[228] According to one report, there was a procession and "much cheering and enthusiasm along the line of route, and the old pioneers received a very hearty greeting". The crowd heard from several speakers, including Ballarat-born Richard Crouch MP, who "was not at all satisfied that the necessity for revolt had at all ended; in fact, he rather advocated a revolt against conventionalism and political cant".[229]

In 1954, a committee of Ballarat locals was formed to coordinate events to mark the centenary of the Eureka Stockade. Historian Geoffrey Blainey, who was in Ballarat, recalls attending one function and finding that no one apart from a small group of communists was there.[230] There was an oration at the Peter Lalor statue, a procession, a pageant at Sovereign Hill, a concert and dance, a dawn service, and a pilgrimage to the Eureka graves. The procession was headed by mounted police and servicemen from the Royal Australian Airforce base at Ballarat dressed in 1850s soldiers' uniforms. There were centenary commemoration events around Australia held under the auspices of the Communist Party of Australia, which in the 1940s named their youth organisation the Eureka Youth League. Catholic Church affiliates also endorsed a Eureka centenary supplement with commemorative events.[231]

Ballarat's best-known tourist destination, Sovereign Hill, was opened in November 1970 as an open-air museum set in the gold rush period. Since 1992, in commemoration of the Eureka Stockade, Sovereign Hill has featured a 90-minute son et lumière "Blood Under the Southern Cross", a sound and light show attraction played under the night skies. It was revised and expanded in 2003.[232][233] The Eureka Flag was temporarily on display at Sovereign Hill during 1987, while renovation work was being carried out at the Art Gallery of Ballarat.[234]

In 1973, Gough Whitlam gave a speech, to mark the largest and most celebrated fragments of the Eureka Flag donated by the descendants of John King going on permanent display at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. He predicted that: "an event like Eureka, with all its associations, with all its potent symbolism, will acquire an aura of excitement and romance, and stir the imagination of the Australian people".[235][note 8]

A purpose-built interpretation centre was erected at the cost of $4 million in March 1998 in the suburb of Eureka near the Eureka Stockade memorial. Designed to be a new landmark for Ballarat, it was known as the Eureka Stockade Centre and then the Eureka Centre.[237] The building originally featured an enormous sail emblazoned with the Eureka Flag.[238] Before its development there was considerable debate over whether a replica or reconstruction of wooden structures was appropriate. It was eventually decided against, and this is seen by many as a reason for the apparent failure of the centre to draw significant tourist numbers. Due primarily to falling visitor numbers the "controversial"[239] Eureka Centre was redeveloped between 2009 and 2011.[240]

A life-size bronze sculpture of the Pikeman's dog was unveiled in the courtyard of the interpretative centre at Eureka Stockade Memorial Park on 5 December 1999 in a ceremony that was attended by the Victorian premier Steve Bracks, former prime minister Gough Whitlam, and the Irish ambassador Richard O'Brien.[241][242]

In 2013 it was relaunched as the Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka with the aid of a further $5 million in funding from both the Australian and Victorian governments and $1.1 million from the City of Ballarat.[243][244] The centrepiece of MADE's collection was the "King" fragments of the Eureka Flag made available on loan from the Art Gallery of Ballarat, that represent 69.01% of the original specimen.[245] In 2018, the City of Ballarat council resolved to assume responsibility for managing the facility.[246] MADE was closed and since being reopened has been called the Eureka Centre Ballarat.[247]

21st century

[edit]

In 2004, the 150th anniversary of the Eureka Stockade was commemorated. In November, the Premier of Victoria Steve Bracks announced that the Ballarat V/Line rail service would be renamed the Eureka Line to mark the 150th anniversary, taking effect from late 2005 at the same time as the renaming of Spencer Street railway station to Southern Cross.[248] The proposal was criticised by community groups including the Public Transport Users Association.[249]

Renaming of the line did not go ahead. The Spencer Street Station redesignation was announced in December 2005. Bracks stated that the change would resonate with Victorians because the Southern Cross "stands for democracy and freedom because it flew over the Eureka Stockade".[250]

An Australian postage stamp featuring the Eureka Flag was released along with a set of commemorative coins. A ceremony in Ballarat known as the lantern walk was held at dawn. Prime Minister John Howard did not attend any commemorative events and refused to allow the Eureka Flag to fly over Parliament House.[251][252]

The Eureka Tower in Melbourne, completed in 2006, is named in honour of the rebellion and features symbolic aspects such as blue glass and white stripes in reference to both the Eureka Flag and a surveyor's measuring staff and a crown of gold glass with a red stripe to represent the blood spilled on the goldfields.[253]

In 2014, to mark the 160th anniversary of the Eureka Rebellion, the Australian Flag Society released a commemorative folk cartoon entitled Fall Back with the Eureka Jack that was inspired by the Eureka Jack mystery.[254]

In June 2022, the City of Ballarat, in conjunction with Eureka Australia, unveiled a new Pathway of Remembrance at the Eureka Stockade Memorial Park commemorating the "35 men who lost their lives during the Eureka Stockade in 1854".[255]

Popular culture

[edit]The Eureka Rebellion has been the inspiration for numerous novels, poems, films, songs, plays and artworks. Much of the Eureka folklore relies heavily on Raffaello Carboni's 1855 book, The Eureka Stockade, which was the first and only comprehensive eyewitness account of the rebellion. Henry Lawson wrote a number of poems about Eureka, as have many novelists. There have been four motion pictures based on the uprising at Ballarat. The first was Eureka Stockade, a 1907 silent film, the second feature film produced in Australia.[256]

There have been a number of plays and songs about the rebellion. The folk song German Teddy concerns Edward Thonen, one of the rebels who dies defending the Eureka Stockade.[257]

See also

[edit]Lists:

Australian rebellions:

General:

Notes

[edit]- ^ There is a report of a meeting held on 23 October 1854 to discuss indemnifying the Bentley Hotel arsonists where "Mr. Kennedy suggested that a tall flag pole should be erected on some conspicuous site, the hoisting of the diggers' flag on which should be the signal for calling together a meeting on any subject which might require immediate consideration".[79]

- ^ At his first public appearance, Lalor acted as secretary for the 17 November 1854 meeting that led to the burning of Bentley's Hotel and moved in favour of establishing a central rebel executive.[86]

- ^ It is currently known that the Eureka rebels came from at least 23 different nations.[122] Carboni recalled that "We were of all nations and colours".[123] The Argus observed that of "the first batch of prisoners brought up for examination, the four examined consisted of one Englishman, one Dane, one Italian, and one negro, and if that is not a foreign collection, we do not know what is".[124] However, according to Professor Sunter's figures, in her sample of 44 rebels, only one hailed from a non-European country.[113] Despite being present on the Ballarat gold fields, there is no record of any Chinese involvement in the Eureka Stockade. John Joseph, an American Negro, and James Campbell, a Jamaican, were both among the thirteen rebel prisoners to go on trial. Andrew Peters, who acted as a police spy, said during cross-examination that "There are some" black men on the diggings. Patrick Lynott recalled that "There were a good many black men" in the rebel camp.[125]

- ^ In The Revolt at Eureka, part of a 1958 illustrated history series for students, the artist Ray Wenban would remain faithful to the first reports of the battle with his rendition featuring two flags flying above the Eureka Stockade.[131] The 1949 motion picture Eureka Stockade produced by Ealing Studios, also features the Union Jack beneath the Eureka Flag during the oath swearing scene.[132]

- ^ Pierson's diary states that:

Charles Evan's diary also mentions that:... some not understanding marshall (sic) law did not put out their lights and the soldiers fired into the tents and killed 2 men and one woman and wounded others, although we were half a mile off we heard the balls whistling over our tents.[152]

Among the victims of last night's unpardonable recklessness were a woman and her infant. The same ball which murdered the mother, ... passed through the child as it lay sleeping in her arms.... Another sufferer is a highly respectable storekeeper, who had his thighbone shattered by a ball as he was walking toward the township.[153]

- ^ In 1873, Lalor also remained a director of the Lothair gold mine at Clunes after the board resolved to bring in low-paid Chinese workers from Ballarat and Creswick to use as strikebreakers after the employees collectively withdrew their labour in an industrial dispute. On 8 December, some 500 men of the Miner's Association, who were "armed with sticks, waddies and pickhandles and led by the Clunes Brass Band, marched around the streets". The striking miners then "demolished a building prepared for the accommodation of the Chinese". At dawn the next day, they formed picket lines at the entrances to the mine to forcibly refuse entry to the Chinese workers, who were under police escort. The company was forced to abandon their plans as the miners began "yelling and cursing and the people of Clunes flung 'a storm of missiles' at the unfortunate troopers and coach-loads of Chinese".[189]

- ^ Victoria became the first jurisdiction in the world to adopt the secret ballot in place of open voting upon commencement of the Electoral Act in 1856. South Australia enacted similar legislation a fortnight later.[206] The colony's electoral commissioner, William Boothby, is recognised as the pioneer of the secret ballot, also known as "the Australian ballot" when it was first introduced in the United States. At the same time, South Australia became the first colony to legislate for full adult male suffrage. Although Victoria's Legislative Assembly was no longer subject to any property qualifications from 1857, they remained for the Legislative Council in terms of membership and eligibility to vote until 1950.[207] Other demands made by franchise activists on the goldfields that were subsequently made law in Victoria include regular elections every three years in 1859 and payment for members of parliament in 1870.[208]