Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Border control

View on Wikipedia

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (December 2023) |

Border control comprises measures taken by governments to monitor[1] and regulate the movement of people, animals, and goods across land, air, and maritime borders. While border control is typically associated with international borders, it also encompasses controls imposed on internal borders within a single state.

Border control measures serve a variety of purposes, ranging from enforcing customs, sanitary and phytosanitary, or biosecurity regulations to restricting migration. While some borders (including most states' internal borders and international borders within the Schengen Area) are open and completely unguarded, others (including the vast majority of borders between countries as well as some internal borders) are subject to some degree of control and may be crossed legally only at designated checkpoints. Border controls in the 21st century are tightly intertwined with intricate systems of travel documents, visas, and increasingly complex policies that vary between countries.

Border controls have significant human and economic costs, including tens of thousands of border deaths. According to one estimate, the indirect economic cost of border controls is many trillions of dollars and the size of the global economy could double if migration restrictions were lifted.

History

[edit]

In medieval Europe, the boundaries between rival countries and centres of power were largely symbolic or consisted of amorphous borderlands, 'marches', and 'debatable lands' of indeterminate or contested status and the real 'borders' consisted of the fortified walls that surrounded towns and cities, where the authorities could exclude undesirable or incompatible people at the gates, from vagrants, beggars and the 'wandering poor', to 'masterless women', lepers, Romani, or Jews.[2]

The concept of border controls has its origins in antiquity. In Asia, the existence of border controls is evidenced in classical texts. The Arthashastra (c. 3rd century BCE) makes mention of passes issued at the rate of one masha per pass to enter and exit the country. Chapter 34 of the Second Book of Arthashastra concerns with the duties of the Mudrādhyakṣa (lit. 'Superintendent of Seals') who must issue sealed passes before a person could enter or leave the countryside.[3] Passports resembling those issued today were an important part of the Chinese bureaucracy as early as the Western Han (202 BCE-220 CE), if not in the Qin dynasty. They required such details as age, height, and bodily features.[4] The passports (zhuan) determined a person's ability to move throughout imperial counties and through points of control. Even children needed passports, but those of one year or less who were in their mother's care may not have needed them.[4]

Medieval period

[edit]In the Golden age of the Islamic Caliphate (medieval time in Europe), a form of passport was the bara'a, a receipt for taxes paid. Border controls were in place to ensure that only people who paid their zakah (for Muslims) or jizya (for dhimmis) taxes could travel freely between different regions of the Caliphate; thus, the bara'a receipt was a "basic passport".[5]

In medieval Europe, passports were issued since at least the reign of Henry V of England, as a means of helping his subjects prove who they were in foreign lands. The earliest reference to these documents is found in an act of Parliament, the Safe Conducts Act 1414 (2 Hen. 5. Stat. 1. c. 6).[6][7] In 1540, granting travel documents in England became a role of the Privy Council of England, and it was around this time that the term "passport" was used. In 1794, issuing British passports became the job of the Office of the Secretary of State.[6] The 1548 Imperial Diet of Augsburg required the public to hold imperial documents for travel, at the risk of permanent exile.[8] During World War I, European governments introduced border passport requirements for security reasons, and to control the emigration of people with useful skills. These controls remained in place after the war, becoming a standard, though controversial, procedure. British tourists of the 1920s complained, especially about attached photographs and physical descriptions, which they considered led to a "nasty dehumanization".[9]

Beginning in the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire established quarantine stations on many of its borders to control disease. For example, along the Greek-Turkish border, all travellers entering and exiting the Ottoman Empire would be quarantined for 9–15 days. The stations were often manned by armed guards. If plague appeared, the Ottoman army would be deployed to enforce border control and monitor disease.[10]

Modern history

[edit]One of the earliest systematic attempts of modern nation states to implement border controls to restrict entry of particular groups were policies adopted by Canada, Australia, and America to curtail immigration of Asians in white settler states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The first anti-East Asian policy implemented in this era was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in America, which was followed suit by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 in Canada, which imposed what came to be called the Chinese head tax. These policies were a sign of injustice and unfair treatment to the Chinese workers because the jobs they engaged in were mostly menial jobs.[11] Similar policies were adopted in various British colonies in Australia over the latter half of the 19th century targeting Asian immigrants arriving as a result of the region's series of gold rushes[12] as well as Kanakas (Pacific Islanders brought into Australia as indentured labourers)[13] who alongside the Asians were perceived by trade unionists and White blue collar workers as a threat to the wages of White settlers.[14] Following the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, these discriminatory border control measures quickly expanded into the White Australia Policy, while subsequent legislation in America (e.g. the Immigration Act of 1891, the Naturalisation Act of 1906, the Immigration Act of 1917, and the Immigration Act of 1924) resulted in an even stricter policy targeting immigrants from both Asia and parts of southern and eastern Europe.

Even following the adoption of measures such as the White Australia Policy and the Chinese Exclusion Act in English-speaking settler colonies, pervasive control of international borders remained a relatively rare phenomenon until the early 20th century, prior to which many states had open international borders either in practice or due to a lack of any legal restriction. John Maynard Keynes identified World War I in particular as the point when such controls became commonplace.[15]

Decolonisation during the twentieth century saw the emergence of mass emigration from nations in the Global South, thus leading former colonial occupiers to introduce stricter border controls.[16] In the United Kingdom this process took place in stages, with British nationality law eventually shifting from recognising all Commonwealth citizens as British subjects to today's complex British nationality law which distinguishes between British citizens, modern British Subjects, British Overseas Citizens, and overseas nationals, with each non-standard category created as a result of attempts to balance border control and the need to mitigate statelessness. This aspect of the rise of border control in the 20th century has proven controversial. The British Nationality Act 1981 has been criticised by experts,[a] as well as by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination of the United Nations,[b] on the grounds that the different classes of British nationality it created are, in fact, closely related to the ethnic origins of their holders.

The creation of British Nationality (Overseas) status, for instance, (with fewer privileges than British citizen status) was met with criticism from many Hong Kong residents who felt that British citizenship would have been more appropriate in light of the "moral debt" owed to them by the UK.[c][d] Some British politicians[e] and magazines[f] also criticised the creation of BN(O) status. In 2020, the British government under Boris Johnson announced a program under which BN(O)s would have leave to remain in the UK with rights to work and study for five years, after which they may apply for settled status. They would then be eligible for full citizenship after holding settled status for 12 months.[22] This was implemented as the eponymously named "British National (Overseas) visa", a residence permit that BN(O)s and their dependent family members have been able to apply for since 31 January 2021.[23][24] BN(O)s and their dependents who arrived in the UK before the new immigration route became available were granted "Leave Outside the Rules" at the discretion of the Border Force to remain in the country for up to six months as a temporary measure.[25] In effect, this retroactively granted BN(O)s a path to right of abode in the United Kingdom. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, about 7,000 people had entered the UK under this scheme between July 2020 and January 2021.[26]

Ethnic tensions created during colonial occupation also resulted in discriminatory policies being adopted in newly independent African nations, such as Uganda under Idi Amin which banned Asians from Uganda, thus creating a mass exodus of the (largely Gujarati[27][28]) Asian community of Uganda. Such ethnically driven border control policies took forms ranging from anti-Asian sentiment in East Africa to Apartheid policies in South Africa and Namibia (then known as Southwest Africa under South African rule) which created bantustans[g] and pass laws[h] to segregate and impose border controls against non-whites, and encouraged immigration of whites at the expense of Blacks as well as Indians and other Asians. Whilst border control in Europe and east of the Pacific have tightened over time,[16] they have largely been liberalized in Africa, from Yoweri Museveni's reversal of Idi Amin's anti-Asian border controls[i] to the fall of Apartheid (and thus racialized border controls) in South Africa.

With the development of border control policies over the course of the 20th century came the standardization of refugee travel documents under the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951[j] and the 1954 Convention travel document[35] for stateless people under the similar 1954 statelessness convention.

COVID-19

[edit]The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 produced a drastic tightening of border controls across the globe. Many countries and regions have imposed quarantines, entry bans, or other restrictions for citizens of or recent travellers to the most affected areas.[36] Other countries and regions have imposed global restrictions that apply to all foreign countries and territories, or prevent their own citizens from travelling overseas.[37] The imposition of border controls has curtailed the spread of the virus, but because they were first implemented after community spread was established in multiple countries in different regions of the world, they produced only a modest reduction in the total number of people infected[38] These strict border controls economic harm to the tourism industry through lost income and social harm to people who were unable to travel for family matters or other reasons. When the travel bans are lifted, many people are expected to resume traveling. However, some travel, especially business travel, may be decreased long-term as lower cost alternatives, such as teleconferencing and virtual events, are preferred.[39] A possible long-term impact has been a decline of business travel and international conferencing, and the rise of their virtual, online equivalents.[40] Concerns have been raised over the effectiveness of travel restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19.[41]

Tactics

[edit]This article may lend undue weight to details of the "how" and "what" rather than "why", impacts, and alternatives. (October 2025) |

Contemporary border control policies are complex and address a variety of distinct phenomena depending on the circumstances and political priorities of the state(s) implementing them. Consequently, there are several aspects of border control which vary in nature and importance from region to region.

Air and maritime borders

[edit]In addition to land borders, countries also apply border control measures to airspace and waters under their jurisdiction. Such measures control access to air and maritime territory as well as extractible resources (e.g. fish, minerals, fossil fuels).

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS),[42] states exercise varying degrees of control over different categories of territorial waters:

- Internal waters: Waters landward of the baseline,[k] over which the state has complete sovereignty: not even innocent passage[l] is allowed without explicit permission from said state. Lakes and rivers are considered internal waters.

- Territorial sea: A state's territorial sea is a belt of coastal waters extending at most 22 kilometres from the baseline[k] of a coastal state. If this would overlap with another state's territorial sea, the border is taken as the median point between the states' baselines, unless the states in question agree otherwise. A state can also choose to claim a smaller territorial sea. The territorial sea is regarded as the sovereign territory of the state, although foreign ships (military and civilian) are allowed innocent passage through it, or transit passage for straits; this sovereignty also extends to the airspace over and seabed below. As a result of UNCLOS, states exercise a similar degree of control over its territorial sea as over land territory and may thus utilise coast guard and naval patrols to enforce border control measures provided they do not prevent innocent or transit passage.

- Contiguous zone: A state's contiguous zone is a band of water extending farther from the outer edge of the territorial sea to up to 44 kilometres (27 miles) from the baseline, within which a state can implement limited border control measures for the purpose of preventing or punishing "infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea". This will typically be 22 kilometres (14 miles) wide, but could be more (if a state has chosen to claim a territorial sea of less than 22 kilometres), or less, if it would otherwise overlap another state's contiguous zone. However, unlike the territorial sea, there is no standard rule for resolving such conflicts and the states in question must negotiate their own compromise. America invoked a contiguous zone out to 44 kilometres from the baseline on 29 September 1999.[43]

- Exclusive economic zone: An exclusive economic zone extends from the baseline[k] to a maximum of 370 kilometres (230 miles). A coastal nation has control of all economic resources within its exclusive economic zone, including fishing, mining, oil exploration, and any pollution of those resources.[44] However, it cannot prohibit passage or loitering above, on, or under the surface of the sea that is in compliance with the laws and regulations adopted by the coastal State in accordance with the provisions of the UN Convention, within that portion of its exclusive economic zone beyond its territorial sea. The only authority a state has over its EEZ is therefore its ability to regulate the extraction or spoliation of resources contained therein and border control measures implemented to this effect focus on the suppression of unauthorised commercial activity.

Vessels not complying with a state's maritime policies may be subject to ship arrest and enforcement action by the state's authorities. Maritime border control measures are controversial in the context of international trade disputes, as was the case following France's detention of British fishermen in October 2021 in the aftermath of Brexit[45][46] or when the Indonesian navy detained the crew of the Seven Seas Conqueress alleging that the vessel was unlawfully fishing within Indonesian territorial waters while the Singaporean government claimed the vessel was in Singaporean waters near Pedra Branca.[47]

Similarly, international law accords each state control over the airspace above its land territory, internal waters, and territorial sea. Consequently, states have the authority to regulate flyover rights and tax foreign aircraft utilising their airspace. Additionally, the International Civil Aviation Organization designates states to administer international airspace, including airspace over waters not forming part of any state's territorial sea. Aircraft unlawfully entering a country's airspace may be grounded and their crews may be detained.

No country has sovereignty over international waters, including the associated airspace. All states have the freedom of fishing, navigation, overflight, laying cables and pipelines, as well as research. Oceans, seas, and waters outside national jurisdiction are also referred to as the high seas or, in Latin, mare liberum (meaning free sea). The 1958 Convention on the High Seas defined "high seas" to mean "all parts of the sea that are not included in the territorial sea or in the internal waters of a State" and where "no State may validly purport to subject any part of them to its sovereignty".[48] Ships sailing the high seas are generally under the jurisdiction of their flag state (if there is one);[49] however, when a ship is involved in certain criminal acts, such as piracy,[50] any nation can exercise jurisdiction under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction regardless of maritime borders.

As part of their air and maritime border control policies, most countries restrict or regulate the ability of foreign airlines and vessels to transport of goods or passengers between sea ports and airports in their jurisdiction, known as cabotage. Restrictions on maritime cabotage apply exist in most countries with territorial and internal waters so as to protect the domestic shipping industry from foreign competition, preserve domestically owned shipping infrastructure for national security purposes, and ensure safety in congested territorial waters.[51] For example, in America, the Jones Act provides for extremely strict restrictions on cabotage.[m] Similarly, China does not permit foreign flagged vessels to conduct domestic transport or domestic transhipments without the prior approval of the Ministry of Transport.[52] While Hong Kong and Macau maintain distinct internal cabotage regimes from the mainland, maritime cabotage between either territory and the mainland is considered domestic carriage and accordingly is off limits to foreign vessels.[52] Similarly, maritime crossings across the Taiwan Strait requires special permits from both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China[n] and are usually off-limits to foreign vessels.[52] In India, foreign vessels engaging in the coasting trade[o] require a licence that is generally only issued when no local vessel is available.[52] Similarly, a foreign vessel may only be issued a licence to engage in cabotage in Brazil if there are no Brazilian flagged vessels available for the intended transport.[52]

As with maritime cabotage, most jurisdictions heavily restrict cabotage in passenger aviation, though rules regarding air cargo are typically more lax. Passenger cabotage is not usually granted under most open skies agreements. Air cabotage policies in the European Union are uniquely liberal insofar as carriers licensed by one member state are permitted to engage in cabotage in any EU member state, with few limitations.[53] Chile has the most liberal air cabotage rules in the world, enacted in 1979, which allow foreign airlines to operate domestic flights, conditional upon reciprocal treatment for Chilean carriers in the foreign airline's country. Countries apply special provisions to the ability of foreign airlines to carry passengers between two domestic destinations through an offshore hub.[p]

Many countries implement air defence identification zones (ADIZs) requiring aircraft approaching within a specified distance of its airspace to contact or seek prior authorization from its military or transport authorities.[57] An ADIZ may extend beyond a country's territory to give the country more time to respond to possibly hostile aircraft.[58] The concept of an ADIZ is not defined in any international treaty and is not regulated by any international body,[58][59] but is nevertheless a well-established aerial border control measure.[q] Usually such zones only cover undisputed territory, do not apply to foreign aircraft not intending to enter territorial airspace, and do not overlap.[59][62]

Biosecurity

[edit]

Biosecurity refers to measures aimed at preventing the introduction and/or spread of harmful organisms (e.g. viruses, bacteria, etc.) to animals and plants in order to mitigate the risk of transmission of infectious disease. In agriculture, these measures are aimed at protecting food crops and livestock from pests, invasive species, and other organisms not conducive to the welfare of the human population. The term includes biological threats to people, including those from pandemic diseases and bioterrorism. The definition has sometimes been broadened to embrace other concepts, and it is used for different purposes in different contexts. The most common category of biosecurity policies are quarantine measures adopted to counteract the spread of disease and, when applied as a component of border control, focus primarily on mitigating the entry of infected individuals, plants, or animals into a country.[63] Other aspects of biosecurity related to border control include mandatory vaccination policies for inbound travellers and measures to curtail the risk posed by bioterrorism or invasive species. Quarantine measures are frequently implemented with regard to the mobility of animals, including both pets and livestock. Notably, in order to reduce the risk of introducing rabies from continental Europe, the United Kingdom used to require that dogs, and most other animals introduced to the country, spend six months in quarantine at an HM Customs and Excise pound. This policy was abolished in 2000 in favour of a scheme generally known as Pet Passports, where animals can avoid quarantine if they have documentation showing they are up to date on their appropriate vaccinations.[64]

In the past, quarantine measures were implemented by European countries in order to curtail the Bubonic Plague and Cholera. In the British Isles, for example, the Quarantine Act 1710 (9 Ann. c. 2) established maritime quarantine policies in an era in which strict border control measures as a whole were yet to become mainstream.[65] The first act was called for due to fears that the plague might be imported from Poland and the Baltic states. A second act of Parliamemt, the Quarantine Act 1721 (8 Geo. 1. c. 10), was due to the prevalence of the plague at Marseille and other places in Provence, France. It was renewed in 1733 after a new outbreak in continental Europe, and again in 1743, due to an epidemic in Messina. A rigorous quarantine clause was introduced into the Levant Act 1752 an act regulating trade with the Levant, and various arbitrary orders were issued during the next twenty years to meet the supposed danger of infection from the Baltic states. Although no plague cases ever came to England during that period, the restrictions on traffic became more stringent, and a very strict Quarantine and Customs Act 1788 (28 Geo. 3. c. 34) was passed, with provisions affecting cargoes in particular. The act was revised in 1801 and 1805, and in 1823–24 an elaborate inquiry was followed by an act making quarantine only at the discretion of the Privy Council, which recognised yellow fever or other highly infectious diseases as calling for quarantine, along with plague. The threat of cholera in 1831 was the last occasion in England of the use of quarantine restrictions. Cholera affected every country in Europe despite all efforts to keep it out. When cholera returned to England in 1849, 1853 and 1865–66, no attempt was made to seal the ports. In 1847 the privy council ordered all arrivals with a clean bill of health from the Black Sea and the Levant to be admitted, provided there had been no case of plague during the voyage and afterwards, the practice of quarantine was discontinued.[66]

In modern maritime law, biosecurity measures for arriving vessels centre around 'pratique', a licence from border control officials permitting a ship to enter port on assurance from the captain that the vessel is free from contagious disease. The clearance granted is commonly referred to as 'free pratique'. A ship can signal a request for 'pratique' by flying a solid yellow square-shaped flag. This yellow flag is the Q flag in the set of international maritime signal flags.[67] In the event that 'free pratique' is not granted, a vessel will be held in quarantine according to biosecurity rules prevailing at the port of entry until a border control officer inspects the vessel.[68] During the COVID-19 pandemic, a controversy arose as to who granted pratique to the Ruby Princess.[69] A related concept is the 'bill of health', a document issued by officials of a port of departure indicating to the officials of the port of arrival whether it is likely that the ship is carrying a contagious disease, either literally on board as fomites or via its crewmen or passengers. As defined in a consul's handbook from 1879:

A bill of health is a document issued by the consul or the public authorities of the port which a ship sails from, descriptive of the health of the port at the time of the vessel's clearance. A clean bill of health certifies that at the date of its issue no infectious disease was known to exist either in the port or its neighbourhood. A suspected or touched bill of health reports that rumours were in circulation that an infectious disease had appeared but that the rumour had not been confirmed by any known cases. A foul bill of health or the absence of a clean bill of health implies that the place the vessel cleared from was infected with a contagious disease. The two latter cases would render the vessel liable to quarantine.[70]

Another category of biosecurity measures adopted by border control organisations is mandatory vaccination. As a result of the prevalence of Yellow Fever across much of the African continent, a significant portion of countries in the region require arriving passengers to present an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (Carte Jaune) certifying that they have received the Yellow Fever vaccine. A variety of other countries require travelers who have visited areas where Yellow Fever is endemic to present a certificate in order to clear border checkpoints as a means of preventing the spread of the disease. Prior to the emergence of COVID-19, Yellow Fever was the primary human disease subjected to de facto vaccine passport measures by border control authorities around the world. Similar measures are in place with regard to Polio and meningococcal meningitis in regions where those diseases are endemic and countries bordering those regions. Prior to the eradication of smallpox, similar Carte Jaune requirements were in force for that disease around the world.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, biosecurity measures have become a highly visible aspect of border control across the globe. Most notably, quarantine and mandatory COVID-19 vaccination for international travelers. Together with a decreased willingness to travel, the implementation of biosecurity measures has had a negative economic and social impact on the travel industry.[71] Slow travel increased in popularity during the pandemic, with tourists visiting fewer destinations during their trips.[72][73]

Biosecurity measures such as restrictions on cross-border travel, the introduction of mandatory vaccination for international travellers, and the adoption of quarantine or mandatory testing measures have helped to contain the spread of COVID-19.[74] While test-based border screening measures may prove effective under certain circumstances, they may fail to detect a significant quantity positive cases if only conducted upon arrival without follow-up. A minimum 10-day quarantine may be beneficial in preventing the spread of COVID-19 and may be more effective if combined with an additional control measure like border screening.[74] A study in Science found that travel restrictions could delay the initial arrival of COVID-19 in a country, but that they produced only modest overall effects unless combined with domestic infection prevention and control measures to considerably reduce transmissions.[75] (That is consistent with prior research on influenza and other communicable diseases.[76][77]) Travel bans early in the pandemic were most effective for isolated locations, such as small island nations.[77]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many jurisdictions across the globe introduced biosecurity measures on internal borders. This ranged from quarantine measures imposed upon individuals crossing state lines within America to prohibitions on interstate travel in Australia.

Customs

[edit]

Each country has its own laws and regulations for the import and export of goods into and out of a country, which its customs authority enforces. The import or export of some goods may be restricted or forbidden, in which case customs controls enforce such policies.[78] Customs enforcement at borders can also entail collecting excise tax and preventing the smuggling of dangerous or illegal goods. A customs duty is a tariff or tax on the importation (usually) or exportation (unusually) of goods.

In many countries, border controls for arriving passengers at many international airports and some road crossings are separated into red and green channels in order to prioritise customs enforcement.[79][80] Within the European Union's common customs area, airports may operate additional blue channels for passengers arriving from within that area. For such passengers, border control may focus specifically on prohibited items and other goods that are not covered by the common policy. Luggage tags for checked luggage traveling within the EU are green-edged so they may be identified.[81][82] In most EU member states, travellers coming from other EU countries within the Schengen Area can use the green lane, although airports outside the Schengen Area or with frequent flights arriving from jurisdictions within Schengen but outside the European Union may use blue channels for convenience and efficiency.

A customs area is an area designated for storage of commercial goods that have not cleared border controls. Commercial goods not yet cleared through customs are often stored in a type of customs area known as a bonded warehouse, until processed or re-exported.[83][84] Ports authorized to handle international cargo generally include recognised bonded warehouses. For the purpose of customs duties, goods within the customs area are treated as being outside the country. This allows easy transshipment to a third country without customs authorities being involved.[83] For this reason, customs areas are usually carefully controlled and fenced to prevent smuggling. However, the area is still territorially part of the country, so the goods within the area are subject to other local laws (for example drug laws and biosecurity regulations), and thus may be searched, impounded or turned back. The term is also sometimes used to define an area (usually composed of several countries) which form a customs union, a customs territory, or to describe the area at airports and ports where travellers are checked through customs.

Sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures are customs measures to protect humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants. The Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, concluded at the Uruguay Round of the Multilateral Trade Negotiations, establishes the types of SPS measures each jurisdiction is permitted to impose. Examples of SPS are tolerance limits for residues, restricted use of substances, labelling requirements related to food safety, hygienic requirements and quarantine requirements. In certain countries, sanitary and phytosanitary measures focuses extensively on curtailing and regulating the import of foreign agricultural products in order to protect domestic ecosystems. For example, Australian border controls restrict most (if not all) food products, certain wooden products and other similar items.[85][86][87] Similar restrictions exist in Canada, America and New Zealand.

Border control in many countries in Asia and the Americas prioritizes enforcing customs laws pertaining to narcotics. For instance, India and Malaysia are focusing resources on eliminating drug smuggling from Myanmar and Thailand respectively. The issue stems largely from the high output of dangerous and illegal drugs in the Golden Triangle as well as in regions further west such as Afghanistan. A similar problem exists east of the Pacific, and has resulted in countries such as Mexico and the United States tightening border control in response to the northward flow of illegal substances from regions such as Colombia. The Mexican Drug War and similar cartel activity in neighboring areas has exacerbated the problem. In certain countries illegal importing, exporting, sale, or possession of drugs constitute capital offences and may result in a death sentence. A 2015 article by The Economist says that the laws of 32 countries provide for capital punishment for drug smuggling, but only in six countries – China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore –are drug offenders known to be routinely executed.[88] Additionally, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia impose mandatory death sentences on individuals caught smuggling restricted substances across their borders. For example, Muhammad Ridzuan Ali was executed in Singapore on May 19, 2017 for drug trafficking.[89] According to a 2011 article by the Lawyers Collective, an NGO in India, "32 countries impose capital punishment for offences involving narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances."[90] South Korean law provides for capital punishment for drug offences,[91] but South Korea has a de facto moratorium on capital punishment as there have been no executions since 1997, even though there are still people on death row and new death sentences continue to be handed down.[92]

Border security

[edit]Border security refers to measures taken by one or more governments to enforce their border control policies.[93] Such measures target a variety of issues, ranging from customs violations and trade in unlawful goods to the suppression of unauthorized migration or travel. The specific border security measures taken by a jurisdiction vary depending on the priorities of local authorities and are affected by social, economic, and geographical factors.

In India, which maintains free movement with Nepal and Bhutan, border security focuses primarily on the Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Myanmar borders. India's primary focus with regard to the border with Bangladesh is to deter unlawful immigration and drug trafficking.[94] On the Pakistani border, the Border Security Force aims to prevent the infiltration of Indian territory by terrorists from Pakistan and other countries in the west (Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, etc.). In contrast, India's border with Myanmar is porous and the 2021 military coup in Myanmar saw an influx of refugees seeking asylum in border states including Mizoram.[95] The refoulement of Rohingya refugees is a contentious aspect of India's border control policy vis à vis Myanmar.[96]

Meanwhile, American border security policy is largely centered on the country's border with Mexico. Security along this border is composed of many distinct elements; including physical barriers, patrol routes, lighting, and border patrol personnel. In contrast, the border with Canada is primarily composed of joint border patrol and security camera programs, forming the longest undefended border in the world. In remote areas along the border with Canada, where staffed border crossings are not available, there are hidden sensors on roads, trails, railways, and wooded areas, which are located near crossing points.[97]

Border security on the Schengen Area's external borders is especially restrictive. Members of the Schengen Agreement are required to apply strict checks on travellers entering and exiting the area. These checks are co-ordinated by the European Union's Frontex agency, and subject to common rules. The details of border controls, surveillance and the conditions under which permission to enter into the Schengen Area may be granted are exhaustively detailed in the Schengen Borders Code.[98] All persons crossing external borders—inbound or outbound—are subject to a check by a border guard. The only exception is for regular cross-border commuters (both those with the right of free movement and third-country nationals) who are well known to the border guards: once an initial check has shown that there is no alert on record relating to them in the Schengen Information System or national databases, they can only be subject to occasional 'random' checks, rather than systematic checks every time they cross the border.[99][100][101] Additionally, border security in Europe is increasingly being outsourced to private companies, with the border security market growing at a rate of 7% per year.[102] In its Border Wars series, the Transnational Institute showed that the arms and security industry helps shape European border security policy through lobbying, regular interactions with EU's border institutions and its shaping of research policy.[103] The institute criticises the border security industry for having a vested interest in increasing border militarisation in order to increase profits. Furthermore, the same companies are also often involved in the arms trade and thus profit twice: first from fuelling the conflicts, repression and human rights abuses that have led refugees to flee their homes and later from intercepting them along their migration routes.[104]

Border walls

[edit]Border walls are a common aspect of border security measures across the world. Border walls generally seek to limit unauthorised travel across an international border and are frequently implemented as a populist response to refugees and economic migrants.

The India-Bangladesh barrier is a 3,406 kilometres (2,116 miles) long fence of barbed wire and concrete just under 3 metres (9 feet 10 inches) high currently under construction.[105] Its stated aim is to limit unauthorised migration.[94] The project has run into several delays and there is no clear completion date for the project yet.[105] Similar to India's barrier with Bangladesh and the proposed wall between America and Mexico, Iran has constructed a wall on its frontier with Pakistan. The wall aims to reduce unauthorised border crossings[106] and stem the flow of drugs,[107] and is also a response to terrorist attacks, notably the one in the Iranian border town of Zahedan on February 17, 2007, which killed thirteen people, including nine Iranian Revolutionary Guard officials.[108] Former president Donald Trump's proposal to build a new wall along the border formed a major feature of his 2016 presidential campaign and, over the course of his presidency, his administration spent approximately US$15 billion on the project, with US$5 billion appropriated from US Customs and Border Protection, US$6.3 billion appropriated from anti-narcotics initiative funded by congress, and US$3.6 billion appropriated from the American military.[109] Members of both the Democratic and Republican parties who opposed Trump's border control policies regarded the border wall as unnecessary or undesirable, arguing that other measures would be more effective at reducing illegal immigration than building a wall, including tackling the economic issues that lead to immigration being a relevant issue altogether, border surveillance or an increase in the number of customs agents.[110] Additionally, in August 2020, the United States constructed 3.8 km of short cable fencing along the border between Abbotsford, British Columbia, and Whatcom County, Washington.[111]

Border walls have formed a major component of European border control policy following the European migrant crisis. The walls at Melilla and at Ceuta on Spain's border with Morocco are designed to curtail the ability of refugees and migrants to enter the European Union via the two Spanish cities on the Moroccan coast. Similar measures have been taken on the Schengen area's borders with Turkey in response to the refugee crisis in Syria. The creation of European Union's collective border security organisation, Frontex, is another aspect of the bloc's growing focus on border security. Within the Schengen Area, border security has become an especially prominent priority for the Hungarian government under right-wing strongman[112][113] Viktor Orbán.[r] Similarly, Saudi Arabia has begun construction of a border barrier or fence between its territory and Yemen to prevent the unauthorized movement of people and goods. The difference between the countries' economic situations means that many Yemenis head to Saudi Arabia to find work. Saudi Arabia does not have a barrier with its other neighbours in the Gulf Cooperation Council, whose economies are more similar. In 2006 Saudi Arabia proposed constructing a security fence along the entire length of its 900 kilometre long desert border with Iraq.[122] As of July 2009 it was reported that Saudis will pay $3.5 billion for a security fence.[123] The combined wall and ditch will be 965 kilometres (600 miles) long and include five layers of fencing, watch towers, night-vision cameras, and radar cameras and manned by 30,000 troops.[124] Elsewhere in Europe, the Republic of Macedonia began erecting a fence on its border with Greece in November 2015.[125]

In 2003, Botswana began building a 480 kilometres (300 miles) long electric fence along its border with Zimbabwe. The official reason for the fence is to stop the spread of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Zimbabweans argue that the height of the fence is clearly intended to keep out people. Botswana has responded that the fence is designed to keep out cattle, and to ensure that entrants have their shoes disinfected at legal border crossings. Botswana also argued that the government continues to encourage legal movement into the country. Zimbabwe was unconvinced, and the barrier remains a source of tension.[126]

-

Mexico–US fence, from California

-

Indian fence, from Hili, Bangladesh

Border checkpoints

[edit]

A Border checkpoint is a place where goods or individuals moving across borders are inspected for compliance with border control measures. Access-controlled borders often have a limited number of checkpoints where they can be crossed without legal sanctions. Arrangements or treaties may be formed to allow or mandate less restrained crossings (e.g. the Schengen Agreement). Land border checkpoints (land ports of entry) can be contrasted with the customs and immigration facilities at seaports, international airports, and other ports of entry.

Checkpoints generally serve two purposes:

- To prevent entrance of individuals who are either undesirable (e.g. criminals or others who pose threats) or simply unauthorised to enter.

- To prevent entrance of goods or contaminants that are illegal or subject to restriction, or to collect tariffs in accordance with customs or quarantine policies.

A border checkpoint at which travellers are permitted to enter a jurisdiction is known as a port of entry. International airports are usually ports of entry, as are road and rail crossings on a land border. Seaports can be used as ports of entry only if a dedicated customs presence is posted there. The choice of whether to become a port of entry is up to the civil authority controlling the port. An airport of entry is an airport that provides customs and immigration services for incoming flights. These services allow the airport to serve as an initial port of entry for foreign visitors arriving in a country. While the terms airport of entry and international airport are generally used interchangeably, not all international airports qualify as airports of entry since international airports without any immigration or customs facilities exist in the Schengen Area whose members have eliminated border controls with each other. Airports of entry are usually larger than domestic airports and often feature longer runways and facilities to accommodate the heavier aircraft commonly used for international and intercontinental travel. International airports often also host domestic flights, which often help feed both passengers and cargo into international ones (and vice versa). Buildings, operations and management have become increasingly sophisticated since the mid-20th century, when international airports began to provide infrastructure for international civilian flights. Detailed technical standards have been developed to ensure safety and common coding systems implemented to provide global consistency. The physical structures that serve millions of individual passengers and flights are among the most complex and interconnected in the world. By the second decade of the 21st century, there were over 1,200 international airports and almost two billion international passengers along with 50 million metric tons (49,000,000 long tons; 55,000,000 short tons) of cargo passing through them annually.

Border inspections are also meant to protect each country's agriculture from pests.[129] National and international phytosanitary authorities maintain databases of border interceptions, occurrences, and establishments.[129] Bebber et al., 2019 analyzes such records and finds that they underreport many important pest species, that island nations are more vulnerable because they have lower border-to-area ratios, and that pests are moving poleward to follow humans' crops as our crops follow global warming.[129]

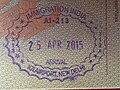

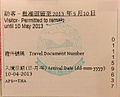

A 'Quilantan' or 'Wave Through' entry is a phenomenon at American border checkpoints authorising a form of non-standard but legal entry without any inspection of travel documents. It occurs when the border security personnel present at a border crossing choose to summarily admit some number of persons without performing a standard interview or document examination.[130] If an individual can prove that they were waved through immigration in this manner, then they are considered to have entered with inspection despite not having answered any questions or received a passport entry stamp.[131] This definition of legal entry only extends to foreigners who entered America at official border crossings and does not provide a path to legal residency for those who did not enter through a recognised crossing.[132]

-

Sterile lounge at Changi Airport Terminal 3 in Singapore. Passengers transiting between international flights at Terminals 1, 2, and 3 of Changi Airport disembark directly into the sterile lounge, and may proceed to their connecting gate without clearing the border checkpoint or completing any other border control formality, and can move between terminals using the Skytrain without clearing any checkpoint.

-

A port of entry at Shir Khan Bandar in northern Afghanistan near the Tajikistan border guarded by American military personnel prior to their withdrawal from Afghanistan, following which the Taliban assumed control over border checkpoints between Afghanistan and its neighbours

-

The Hong Kong–Macau Ferry Terminal in Sheung Wan is a sea port of entry to Hong Kong and an example of an internal border checkpoint where travellers arriving from or departing for other cities in the Pearl River Delta are subject to border control measures.

-

The cruise ship pier at Ocean Terminal is also a sea port of entry to Hong Kong. While the HK-Macau Ferry Terminal is a port of entry for travellers from other Chinese cities in the Pearl River Delta, the Ocean Terminal is a port of entry for visitors arriving on cruise ships from a wider variety of jurisdictions.

Border zones

[edit]Border zones are areas near borders that have special restrictions on movement. Governments may forbid unauthorised entry to or exit from border zones and restrict property ownership in the area. The zones function as buffer zones specifically monitored by border patrols in order to prevent unauthorised cross-border travel. Border zones enable authorities to detain and prosecute individuals suspected of being or aiding undocumented migrants, smugglers, or spies without necessarily having to prove that the individuals in question actually engaged in the suspected unauthorised activity since, as all unauthorised presence in the area is forbidden, the mere presence of an individual permits authorities to arrest them. Border zones between hostile states can be heavily militarised, with minefields, barbed wire, and watchtowers. Some border zones are designed to prevent illegal immigration or emigration and do not have many restrictions but may operate checkpoints to check immigration status. In most places, a border vista is usually included and/or required. In some nations, movement inside a border zone without a licence is an offence and will result in arrest. No probable cause is required as mere presence inside the zone is an offence, if it is intentional.[133] Even with a license to enter, photography, making fires, and carrying of firearms and hunting are prohibited.

Examples of international border zones are the Border Security Zone of Russia and the Finnish border zone on the Finnish–Russian border. There are also intra-country zones such as the Cactus Curtain surrounding the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba, the Korean Demilitarised Zone along the North Korea-South Korea demarcation line and the Frontier Closed Area in Hong Kong. Important historical examples are the Wire of Death set up by the German Empire to control the Belgium–Netherlands border and the Iron Curtain, a set of border zones maintained by the Soviet Union and its satellite states along their borders with Western states. One of the most militarised parts was the restricted zone of the inner German border. While initially and officially the zone was for border security, eventually it was engineered to prevent escape from the Soviet sphere into the West. Ultimately, the Eastern Bloc governments resorted to using lethal countermeasures against those trying to cross the border, such as mined fences and orders to shoot anyone trying to cross into the West. The restrictions on building and habitation made the area a "green corridor", today established as the European Green Belt.

In the area stretching inwards from its internal border with the mainland, Hong Kong maintains a Frontier Closed Area out of bounds to those without special authorisation. The area was established in the 1950s when Hong Kong was under British administration as a consequence of the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory prior to the Transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997. The purposes of the area were to prevent illegal immigration and smuggling; smuggling had become prevalent as a consequence of the Korean War. Today, under the one country, two systems policy, the area continues to be used to curtail unauthorized migration to Hong Kong and the smuggling of goods in either direction.

As a result of the partition of the Korean peninsula by America and the Soviet Union after World War II, and exacerbated by the subsequent Korean War, there is a Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) spanning the de facto border between North and South Korea. The DMZ follows the effective boundaries as of the end of the Korean War in 1953. Similarly to the Frontier Closed Area in Hong Kong, this zone and the defence apparatus that exists on both sides of the border serve to curtail unauthorised passage between the two sides. In South Korea, there is an additional fenced-off area between the Civilian Control Line (CCL) and the start of the Demilitarized Zone. The CCL is a line that designates an additional buffer zone to the Demilitarized Zone within a distance of 5 to 20 kilometres (3.1 to 12.4 miles) from the Southern Limit Line of the Demilitarized Zone. Its purpose is to limit and control the entrance of civilians into the area in order to protect and maintain the security of military facilities and operations near the Demilitarized Zone. The commander of the 8th US Army ordered the creation of the CCL and it was activated and first became effective in February 1954.[134] The buffer zone that falls south of the Southern Limit Line is called the Civilian Control Zone. Barbed wire fences and manned military guard posts mark the CCLe. South Korean soldiers typically accompany tourist buses and cars travelling north of the CCL as armed guards to monitor the civilians as well as to protect them from North Korean intruders. Most of the tourist and media photos of the "Demilitarised Zone fence" are actually photos of the CCL fence. The actual Demilitarised Zone fence on the Southern Limit Line is completely off-limits to everybody except soldiers and it is illegal to take pictures of the Demilitarized Zone fence.

Similarly, the whole estuary of the Han River in the Korean Peninsula is deemed a "Neutral Zone" and is officially off-limits to all civilian vessels. Only military vessels are allowed within this neutral zone.[s] In recent years, Chinese fishing vessels have taken advantage of the tense situation in the Han River Estuary Neutral Zone and illegally fished in this area due to both North Korean and South Korean navies never patrolling this area due to the fear of naval battles breaking out. This has led to firefights and sinkings of boats between Chinese fishermen and South Korean Coast Guard.[136][137] On January 30, 2019, North Korean and South Korean military officials signed a landmark agreement that would open the Han River Estuary to civilian vessels for the first time since the Armistice Agreement in 1953. The agreement was scheduled to take place in April 2019 but the failure of the 2019 Hanoi Summit indefinitely postponed these plans.[138][139][140]

The Green Line separating Southern Cyprus and Northern Cyprus is a demilitarised border zone operated by the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus[t] operate and patrol within the buffer zone. The buffer zone was established in 1974 due to ethnic tensions between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. The green line is similar in nature to the 38th parallel separating the Republic of Korea and North Korea.

Some border zones, referred to as border vistas, are composed of legally mandated cleared space between two areas of foliage located at an international border intended to provide a clear demarcation line between two jurisdictions. Border vistas are most commonly found along undefended international boundary lines, where border security is not as much of a necessity and a built barrier is undesired, and are a treaty requirement for certain borders. An example of a border vista is a 6-metre (20-foot) cleared space around unguarded portions of the Canada–United States border.[141] Similar clearings along the border line are provided for by many international treaties. For example, the 2006 border management treaty between Russia and China provides for a 15-metre (49-foot) cleared strip along the two nations' border.[142]

In 2024, Egypt announced that they are building a buffer zone on the Egypt Gaza border.[143][144]

-

Control Line, Imjingak, South Korea

-

Civilian Control Line, outside the DMZ, from South

-

Korean DMZ from North

-

Finland–Russia border, start of the Finnish border zone

-

Vista at the Norway–Russia border, seen from the Russia-Norway-Finland tripoint

Immigration law

[edit]| Immigration |

|---|

| General |

| History and law |

|

| Social processes |

| Political Theories |

| Causes |

| Opposition and reform |

Immigration law refers to the national statutes, regulations, and legal precedents governing immigration into and deportation from a country. Strictly speaking, it is distinct from other matters such as naturalisation and citizenship, although they are often conflated. Immigration laws vary around the world, as well as according to the social and political climate of the times, as acceptance of immigrants sways from the widely inclusive to the deeply nationalist and isolationist. Countries frequently maintain laws which regulate both the rights of entry and exit as well as internal rights, such as the duration of stay, freedom of movement, and the right to participate in commerce or government. National laws regarding the immigration of citizens of that country are regulated by international law. The United Nations' International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights mandates that all countries allow entry to their own citizens.[145]

Immigration policies

[edit]Diaspora communities

[edit]

Certain countries adopt immigration policies designed to be favourable towards members of diaspora communities with a connection to the country. For example, the Indian government confers Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) status on foreign citizens of Indian origin to live and work indefinitely in India. OCI status was introduced in response to demands for dual citizenship by the Indian diaspora, particularly in countries with large populations of Indian origin.[u] It was introduced by The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2005 in August 2005.[146][147] Similar to OCI status, the UK Ancestry visa exempts members of the British diaspora[v] from usual immigration controls. Poland issued the Karta Polaka to citizens of certain northeast European countries with Polish ancestry, but later expanded it to the worldwide Polonia.

Some nations recognise a right of return for people with ancestry in that country or a connection to a particular ethnic group. A notable example of this is the right of Sephardi Jews to acquire Spanish nationality by virtue of their community's Spanish origins. Similar exemptions to immigration controls exist for people of Armenian origin seeking to acquire Armenian citizenship. Ghana, similarly, grants an indefinite right to stay in Ghana to members of the African diaspora regardless of citizenship.[149] Similarly, Israel maintains a policy permitting members of the Jewish diaspora to immigrate to Israel regardless of prior nationality.

South Korean immigration policy is relatively unique in that, as a consequence of its claim over the territory currently administered by North Korea, citizens of North Korea are regarded by the South as its own citizens by birth.[150] As a result, North Korean refugees in China often attempt to travel to countries such as Thailand which, while not offering asylum to North Koreans, classifies them as unauthorized immigrants and deports them to South Korea instead of North Korea.[151][152][153] At the same time, the policy has operated to prevent pro-North Korea Zainichi Koreans recognised by Japan as Chōsen-seki from entering South Korea without special permission from the South Korean authorities as, despite being regarded as citizens of the Republic of Korea and members of the Korean diaspora, they generally refuse to exercise that status.[154]

Open borders

[edit]

An open border is the deregulation and or lack of regulation on the movement of persons between nations and jurisdictions, this does not apply to trade or movement between privately owned land areas.[155] Most nations have open borders for travel within their nation of travel, though more authoritarian states may limit the freedom of internal movement of its citizens, as for example in the former USSR. However, only a handful of nations have deregulated open borders with other nations, an example of this being European countries under the Schengen Agreement or the open Belarus-Russia border.[156] Open borders used to be very common among all nations, however this became less common after the First World War, which led to the regulation of open borders, making them less common and no longer feasible for most industrialised nations.[157]

Open borders are the norm for borders between subdivisions within the boundaries of sovereign states, though some countries do maintain internal border controls (for example between the People's Republic of China mainland and the special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau; or between the American mainland, the unincorporated territories[w] other than Puerto Rico, and Hawaii.[x] Open borders are also usual between member states of federations, though (very rarely) movement between member states may be controlled in exceptional circumstances.[y] Federations, confederations and similar multi-national unions typically maintain external border controls through a collective border control system, though they sometimes have open borders with other non-member states through special international agreements – such as between Schengen Agreement countries as mentioned above.

Presently, open border agreements of various types are in force in several areas around the world, as outlined below:

- Asia and Oceania:

- Under the 1950 Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship, India and Nepal maintain a similar arrangement to the CTA and the Union State. Indians and Nepalis are not subject to any migration controls in each other's countries and there are few controls on land travel by citizens across the border.

- India and Bhutan also have a similar programme in place The border between Jaigaon, in the Indian state of West Bengal, and the city of Phuentsholing is essentially open, and although there are internal checkpoints, Indians (as outlined under the Visa policy of Bhutan are allowed to proceed throughout Bhutan with a voter's ID or an identity slip from the Indian consulate in Phuentsholing. Similarly, Bhutanese passport holders enjoy free movement in India.

- Thailand and Cambodia: Whilst not as liberal as the policies concerning the Indo-Nepalese and Indo-Bhutanese borders, Thailand and Cambodia have begun issuing combined visas to certain categories of tourists applying at specific Thai or Cambodian embassies and consulates in order to enable freer border crossings between the two countries.[159] The policy is currently in force for nationals of America and several European (primarily EU, EEA, and GCC) and Oceanian countries as well as for Indian and Chinese nationals residing in Singapore.[160]

- Australia and New Zealand: Similar to the agreement between India and Nepal, Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement between Australia and New Zealand is a free movement agreement citizens of each country to travel freely between them and allowing citizens and some permanent residents to reside, visit, work, study in the other country for an indefinite period, with some restrictions.[161][162] The arrangement came into effect in 1973, and allows citizens of each country to reside and work in the other country, with some restrictions. Other details of the arrangement have varied over time. From 1 July 1981, all people entering Australia (including New Zealand citizens) have been required to carry a passport. Since 1 September 1994 Australia, has had a universal visa requirement, and to specifically cater for the continued free movement of New Zealanders to Australia, the Special Category Visa was introduced for New Zealanders.

- Central America :The Central America-4 Border Control Agreement abolishes border controls for land travel between El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. However, this does not apply to air travel.

- Europe and the Middle East

- Union State of Russia and Belarus The Union State of Russia and Belarus is a supranational union of Russia and Belarus, which eliminates all border controls between the two nations. Before a visa agreement was signed in 2020, each country maintained its own visa policies, thus resulting in non-citizens of the two countries generally being barred from travelling directly between the two. However, since the visa agreement was signed, each side recognises the other's visas, which means that third-country citizens can enter both countries with a visa from either country.[163]

- Western Europe: The two most significant free travel areas in Western Europe are the Schengen Area, in which very little if any border control is generally visible, and the Common Travel Area (CTA), which partially eliminates such controls for nationals of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Between countries in the Schengen Area, and to an extent within the CTA on the British Isles, internal border control is often virtually unnoticeable, and often only performed by means of random car or train searches in the hinterland, while controls at borders with non-member states may be rather strict.

- Gulf Cooperation Council: Members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, or GCC, allow each other's citizens freedom of movement in an arrangement similar to the CTA and to that between India and Nepal. Between 5 June 2017 and 5 January 2021, freedom of movement in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain was suspended for Qataris as a result of the Saudi-led blockade of the country.

-

Visa policy of Bhutan, showing the free movement arrangement between India and Bhutan

-

Visa policy of Nepal, showing free movement between India and Nepal under the 1950 treaty

-

Open Schengen Area border crossing between Germany and the Netherlands

-

Open Schengen Area border crossing at the France-Monaco border (was open long before Schengen started)

-

Open Schengen Area border crossing at the Swiss-Liechtenstein border (was open long before Schengen started)

-

Open Schengen Area border crossing at the Slovenian-Italian border, with abandoned rain shelter

-

A Schengen internal border crossing marked only by a blue sign indicating the country being entered. The smaller white sign announces entry into the state of Bavaria.

-

New Zealand visa stamp issued under Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement on an Australian travel document

-

Irish border at Killeen (within CTA) marked only by a metric speed sign, as the Republic of Ireland uses the metric system whilst British road signs use imperial units

Hostile environment policies

[edit]Certain jurisdictions gear their immigration policies toward creating a hostile environment for undocumented migrants in order to deter migration by creating an unwelcoming atmosphere for potential and existing immigrants. Notably, the British Home Office adopted a set of administrative and legislative measures designed to make staying in the United Kingdom as difficult as possible for people without leave to remain, in the hope that they may "voluntarily leave".[164][165][166][167][168] The Home Office policy was first announced in 2012 under the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition.[169] The policy was implemented pursuant to the 2010 Conservative Party Election Manifesto.[170][171][172] The policy has been criticized for being unclear, has led to many incorrect threats of deportation and has been called "Byzantine" by the England and Wales Court of Appeal for its complexity.[173][174][175][176][177][178][179]

Similarly, anti-immigration movements in America have advocated for policies aimed at creating a hostile environment for intended and existing immigrants at various points in history. Historical examples include the nativist Know Nothing movement of the mid-19th century, which advocated hostile policies against Catholic immigrants; the Workingman's Party, which promoted xenophobic attitudes toward Asians in California during the late-19th century, a sentiment that ultimately led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; the Immigration Restriction League, which advocated xenophobic policies against southern and eastern Europe during the late-19th and early 20th centuries, and the joint congressional Dillingham Commission. After World War I, these cumulatively resulted in the highly restrictive Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924. Over the first two decades of the 21st century, the Republican Party adopted an increasingly nativist platform, advocating against sanctuary cities and in favour of building a wall with Mexico and reducing the number of immigrants permitted to settle in the country. Ultimately, the Trump administration furthered many of these policy goals, including the adoption of harsh policies such as the Remain in Mexico and family separation policies vis à vis refugees and migrants arriving from Central America via Mexico. Islamophobic policies such as the travel ban targeted primarily at Muslim-majority countries also feature prominently in attempts to create a hostile environment for immigrants perceived by populists as not belonging to the predominant WASP culture in the United States.

India's citizenship registration policy serves to create a hostile environment for the country's Muslim community in the regions in which it has been implemented.[180] The Indian government is presently in the process of building several detention camps throughout India in order to detain people not listed on the register.[181] On January 9, 2019, the Union government released a '2019 Model Detention Manual', which said that every city or district, having a major immigration check post, must have a detention centre.[182] The guidelines suggest detention centres with 3 metres (9 feet 10 inches) high boundary walls covered with barbed wires.[183][184]

International zones

[edit]An international zone is any area not fully subject to the border control policies of the state in which it is located. There are several types of international zones ranging from special economic zones and sterile zones at ports of entry exempt from customs rules to concessions over which administration is ceded to one or more foreign states. International zones may also maintain distinct visa policies from the rest of the surrounding state.

Internal border controls

[edit]This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (April 2022) |

Internal border controls are measures implemented to control the flow of people or goods within a given country. Such measures take a variety of forms ranging from the imposition of border checkpoints to the issuance of internal travel documents and vary depending on the circumstances in which they are implemented. Circumstances resulting in internal border controls include increasing security around border areas (e.g. internal checkpoints in America or Bhutan near border regions), preserving the autonomy of autonomous or minority areas (e.g. border controls between Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, and Sarawak; border controls between Hong Kong, Macau, and mainland China), preventing unrest between ethnic groups (e.g. Northern Ireland's peace walls, border controls in Tibet and Northeastern India), and disputes between rival governments (e.g. between the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary internal border controls were introduced in jurisdictions across the globe. For instance, travel between Australian states and territories was prohibited or restricted by state governments at various points of the pandemic either in conjunction with sporadic lockdowns or as a stand-alone response to COVID-19 outbreaks in neighbouring states.[185][186][187] Internal border controls were also introduced at various stages of Malaysia's Movement Control Order, per which interstate travel was restricted depending on the severity of ongoing outbreaks. Similarly, internal controls were introduced by national authorities within the Schengen Area, though the European Union ultimately rejected the idea of suspending the Schengen Agreement per se.[188][189]

Asia

[edit]Internal border controls exist in many parts of Asia. For example, travellers visiting minority regions in India and China often require special permits to enter.[z] Internal air and rail travel within non-autonomous portions of India and mainland China also generally require travel documents to be checked by government officials as a form of the interior border checkpoint. For such travel within India, Indian citizens may utilise their Voter ID, National Identity Card, passport, or other proof of Indian citizenship whilst Nepali nationals may present any similar proof of Napali citizenship. Meanwhile, for such travel within mainland China, Chinese nationals from the mainland are required to use their national identity cards.

China

[edit]Within China, extensive border controls are maintained for those travelling between the mainland, special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau. Foreign nationals need to present their passports or other required types of travel documents when travelling between these jurisdictions. For Chinese nationals (including those with British National (Overseas) status), there are special documents[aa] for travel between these territories. Internal border controls in China have also resulted in the creation of special permits allowing Chinese citizens to immigrate to or reside in other immigration areas within the country.[ab]

China also maintains distinct, relaxed border control policies in the Special Economic Zones of Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Xiamen.[191][192] Nationals of most countries[ac] can obtain a limited area visa upon arrival in these regions, which permit them to stay within these cities without proceeding further into other parts of mainland China. Visas for Shenzhen are valid for 5 days, and visas for Xiamen and Zhuhai are valid for 3 days. The duration of stay starts from the next day of arrival.[194] The visa can only be obtained only upon arrival at Luohu Port, Huanggang Port Control Point, Fuyong Ferry Terminal or Shekou Passenger Terminal for Shenzhen;[195] Gongbei Port of Entry, Hengqin Port or Jiuzhou Port for Zhuhai;[196] and Xiamen Gaoqi International Airport for Xiamen.[197]

Similarly, China permits nationals of non—visa-exempt ASEAN countries[ad] to visit Guilin without a visa for a maximum of 6 days if they travel with an approved tour group and enter China from Guilin Liangjiang International Airport. They may not visit other cities within Guangxi or other parts of mainland China.[198]

Neither the People's Republic of China nor the Republic of China recognizes the passports issued by the other and neither considers travel between mainland China and areas controlled by the Republic of China[n] as formal international travel. There are arrangements exist for travel between territories controlled by the Republic of China and territories controlled by the People's Republic of China.[ae]

More generally, authorities in mainland China maintain a system of residency registration known as hukou (Chinese: 户口; lit. 'household individual'), by which government permission is needed to formally change one's place of residence. It is enforced with identity cards. This system of internal border control measures effectively limited internal migration before the 1980s but subsequent market reforms caused it to collapse as a means of migration control. An estimated 150 to 200 million people are part of the "blind flow" and have unofficially migrated, generally from poor, rural areas to wealthy, urban ones. However, unofficial residents are often denied official services such as education and medical care and are sometimes subject to both social and political discrimination. In essence, the denial of social services outside an individual's registered area of residence functions as an internal border control measure geared toward dissuading migration within the mainland.

Bhutan

[edit]Meanwhile, in Bhutan, accessible by road only through India, there are interior border checkpoints (primarily on the Lateral Road) and, additionally, certain areas require special permits to enter, whilst visitors not proceeding beyond the border city of Phuentsholing do not need permits to enter for the day (although such visitors are de facto subject to Indian visa policy since they must proceed through Jaigaon). Individuals who are not citizens of India, Bangladesh, or the Maldives must obtain both their visa and any regional permits required through a licensed tour operator prior to arriving in the country. Citizens of India, Bangladesh, and the Maldives may apply for regional permits for restricted areas online.[199]

Malaysia

[edit]Another example is the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, which have maintained their own border controls[200] since joining Malaysia in 1963. The internal border control is asymmetrical; while Sabah and Sarawak impose immigration control on Malaysian citizens from other states, there is no corresponding border control in Peninsular Malaysia, and Malaysians from Sabah and Sarawak have unrestricted right to live and work in the Peninsular. For social and business visits less than three months, Malaysian citizens may travel between the Peninsular, Sabah and Sarawak using the Malaysian identity card (MyKad) or Malaysian passport, while for longer stays in Sabah and Sarawak they are required to have an Internal Travel Document or a passport with the appropriate residential permit.

North Korea

[edit]The most restrictive internal border controls are in North Korea. Citizens are not allowed to travel outside their areas of residence without explicit authorisation, and access to the capital city of Pyongyang is heavily restricted.[201][202] Similar restrictions are imposed on tourists, who are only allowed to leave Pyongyang on government-authorised tours to approved tourist sites.

Europe