Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Quotient group

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

A quotient group or factor group is a mathematical group obtained by aggregating similar elements of a larger group using an equivalence relation that preserves some of the group structure (the rest of the structure is "factored out"). For example, the cyclic group of addition modulo n can be obtained from the group of integers under addition by identifying elements that differ by a multiple of and defining a group structure that operates on each such class (known as a congruence class) as a single entity. It is part of the mathematical field known as group theory.

For a congruence relation on a group, the equivalence class of the identity element is always a normal subgroup of the original group, and the other equivalence classes are precisely the cosets of that normal subgroup. The resulting quotient is written , where is the original group and is the normal subgroup. This is read as '', where is short for modulo. (The notation should be interpreted with caution, as some authors (e.g., Vinberg[1]) use it to represent the left cosets of in for any subgroup , even though these cosets do not form a group if is not normal in . Others (e.g., Dummit and Foote[2]) use this notation to refer only to the quotient group, with the appearance of this notation implying that is normal in .)

Much of the importance of quotient groups is derived from their relation to homomorphisms. The first isomorphism theorem states that the image of any group under a homomorphism is always isomorphic to a quotient of . Specifically, the image of under a homomorphism is isomorphic to where denotes the kernel of .

The dual notion of a quotient group is a subgroup, these being the two primary ways of forming a smaller group from a larger one. Any normal subgroup has a corresponding quotient group, formed from the larger group by eliminating the distinction between elements of the subgroup. In category theory, quotient groups are examples of quotient objects, which are dual to subobjects.

Definition and illustration

[edit]Given a group and a subgroup , and a fixed element , one can consider the corresponding left coset: . Cosets are a natural class of subsets of a group; for example consider the abelian group of integers, with operation defined by the usual addition, and the subgroup of even integers. Then there are exactly two cosets: , which are the even integers, and , which are the odd integers (here we are using additive notation for the binary operation instead of multiplicative notation).

For a general subgroup , it is desirable to define a compatible group operation on the set of all possible cosets, . This is possible exactly when is a normal subgroup, see below. A subgroup of a group is normal if and only if the coset equality holds for all . A normal subgroup of is denoted .

Definition

[edit]Let be a normal subgroup of a group . Define the set to be the set of all left cosets of in . That is, .

Since the identity element , . Define a binary operation on the set of cosets, , as follows. For each and in , the product of and , , is . This works only because does not depend on the choice of the representatives, and , of each left coset, and . To prove this, suppose and for some . Then

This depends on the fact that is a normal subgroup. It still remains to be shown that this condition is not only sufficient but necessary to define the operation on .

To show that it is necessary, consider that for a subgroup of , we have been given that the operation is well defined. That is, for all and for .

Let and . Since , we have .

Now, and .

Hence is a normal subgroup of .

It can also be checked that this operation on is always associative, has identity element , and the inverse of element can always be represented by . Therefore, the set together with the operation defined by forms a group, the quotient group of by .

Due to the normality of , the left cosets and right cosets of in are the same, and so, could have been defined to be the set of right cosets of in .

Example: Addition modulo 6

[edit]For example, consider the group with addition modulo 6: . Consider the subgroup , which is normal because is abelian. Then the set of (left) cosets is of size three:

The binary operation defined above makes this set into a group, known as the quotient group, which in this case is isomorphic to the cyclic group of order 3.

Motivation for the name "quotient"

[edit]The quotient group can be compared to division of integers. When dividing 12 by 3 one obtains the result 4 because one can regroup 12 objects into 4 subcollections of 3 objects. The quotient group is the same idea, although one ends up with a group for a final answer instead of a number because groups have more structure than an arbitrary collection of objects: in the quotient , the group structure is used to form a natural "regrouping". These are the cosets of in . Because we started with a group and normal subgroup, the final quotient contains more information than just the number of cosets (which is what regular division yields), but instead has a group structure itself.

Examples

[edit]Even and odd integers

[edit]Consider the group of integers (under addition) and the subgroup consisting of all even integers. This is a normal subgroup, because is abelian. There are only two cosets: the set of even integers and the set of odd integers, and therefore the quotient group is the cyclic group with two elements. This quotient group is isomorphic with the set with addition modulo 2; informally, it is sometimes said that equals the set with addition modulo 2.

Example further explained...

- Let be the remainders of when dividing by . Then, when is even and when is odd.

- By definition of , the kernel of , , is the set of all even integers.

- Let . Then, is a subgroup, because the identity in , which is , is in , the sum of two even integers is even and hence if and are in , is in (closure) and if is even, is also even and so contains its inverses.

- Define as for and is the quotient group of left cosets; .

- Note that we have defined , is if is odd and if is even.

- Thus, is an isomorphism from to .

Remainders of integer division

[edit]A slight generalization of the last example. Once again consider the group of integers under addition. Let be any positive integer. We will consider the subgroup of consisting of all multiples of . Once again is normal in because is abelian. The cosets are the collection . An integer belongs to the coset , where is the remainder when dividing by . The quotient can be thought of as the group of "remainders" modulo . This is a cyclic group of order .

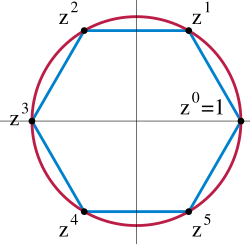

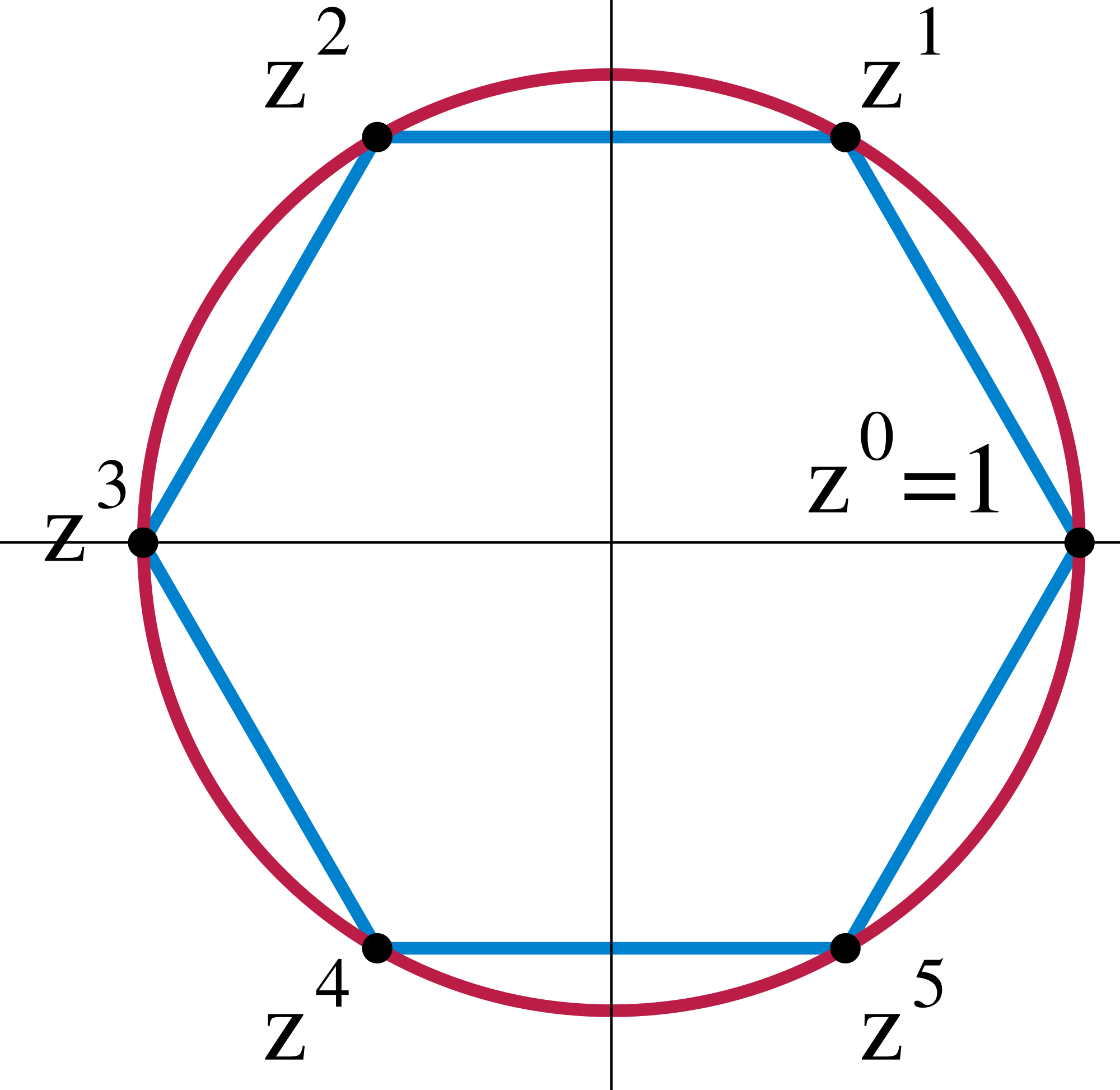

Complex integer roots of 1

[edit]

The twelfth roots of unity, which are points on the complex unit circle, form a multiplicative abelian group , shown on the picture on the right as colored balls with the number at each point giving its complex argument. Consider its subgroup made of the fourth roots of unity, shown as red balls. This normal subgroup splits the group into three cosets, shown in red, green and blue. One can check that the cosets form a group of three elements (the product of a red element with a blue element is blue, the inverse of a blue element is green, etc.). Thus, the quotient group is the group of three colors, which turns out to be the cyclic group with three elements.

Real numbers modulo the integers

[edit]Consider the group of real numbers under addition, and the subgroup of integers. Each coset of in is a set of the form , where is a real number. Since and are identical sets when the non-integer parts of and are equal, one may impose the restriction without change of meaning. Adding such cosets is done by adding the corresponding real numbers, and subtracting 1 if the result is greater than or equal to 1. The quotient group is isomorphic to the circle group, the group of complex numbers of absolute value 1 under multiplication, or correspondingly, the group of rotations in 2D about the origin, that is, the special orthogonal group . An isomorphism is given by (see Euler's identity).

Matrices of real numbers

[edit]If is the group of invertible real matrices, and is the subgroup of real matrices with determinant 1, then is normal in (since it is the kernel of the determinant homomorphism). The cosets of are the sets of matrices with a given determinant, and hence is isomorphic to the multiplicative group of non-zero real numbers. The group is known as the special linear group .

Integer modular arithmetic

[edit]Consider the abelian group (that is, the set with addition modulo 4), and its subgroup . The quotient group is . This is a group with identity element , and group operations such as . Both the subgroup and the quotient group are isomorphic with .

Integer multiplication

[edit]Consider the multiplicative group . The set of th residues is a multiplicative subgroup isomorphic to . Then is normal in and the factor group has the cosets . The Paillier cryptosystem is based on the conjecture that it is difficult to determine the coset of a random element of without knowing the factorization of .

Properties

[edit]The quotient group is isomorphic to the trivial group (the group with one element), and is isomorphic to .

The order of , by definition the number of elements, is equal to , the index of in . If is finite, the index is also equal to the order of divided by the order of . The set may be finite, although both and are infinite (for example, ).

There is a "natural" surjective group homomorphism , sending each element of to the coset of to which belongs, that is: . The mapping is sometimes called the canonical projection of onto . Its kernel is .

There is a bijective correspondence between the subgroups of that contain and the subgroups of ; if is a subgroup of containing , then the corresponding subgroup of is . This correspondence holds for normal subgroups of and as well, and is formalized in the lattice theorem.

Several important properties of quotient groups are recorded in the fundamental theorem on homomorphisms and the isomorphism theorems.

If is abelian, nilpotent, solvable, cyclic or finitely generated, then so is .

If is a subgroup in a finite group , and the order of is one half of the order of , then is guaranteed to be a normal subgroup, so exists and is isomorphic to . This result can also be stated as "any subgroup of index 2 is normal", and in this form it applies also to infinite groups. Furthermore, if is the smallest prime number dividing the order of a finite group, , then if has order , must be a normal subgroup of .[3]

Given and a normal subgroup , then is a group extension of by . One could ask whether this extension is trivial or split; in other words, one could ask whether is a direct product or semidirect product of and . This is a special case of the extension problem. An example where the extension is not split is as follows: Let , and , which is isomorphic to . Then is also isomorphic to . But has only the trivial automorphism, so the only semi-direct product of and is the direct product. Since is different from , we conclude that is not a semi-direct product of and .

Quotients of Lie groups

[edit]If is a Lie group and is a normal and closed (in the topological rather than the algebraic sense of the word) Lie subgroup of , the quotient is also a Lie group. In this case, the original group has the structure of a fiber bundle (specifically, a principal -bundle), with base space and fiber . The dimension of equals .[4]

Note that the condition that is closed is necessary. Indeed, if is not closed then the quotient space is not a T1-space (since there is a coset in the quotient which cannot be separated from the identity by an open set), and thus not a Hausdorff space.

For a non-normal Lie subgroup , the space of left cosets is not a group, but simply a differentiable manifold on which acts. The result is known as a homogeneous space.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Vinberg, Ė B. (2003). A course in algebra. Graduate studies in mathematics. Providence, R.I: American Mathematical Society. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8218-3318-6.

- ^ Dummit & Foote (2003, p. 95)

- ^ Dummit & Foote (2003, p. 120)

- ^ John M. Lee, Introduction to Smooth Manifolds, Second Edition, theorem 21.17

References

[edit]- Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (2003), Abstract Algebra (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-43334-7

- Herstein, I. N. (1975), Topics in Algebra (2nd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-02371-X

Quotient group

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A quotient group, also known as a factor group, is constructed from a group and a normal subgroup of .[3] Specifically, denotes the set of all left cosets of in , given by , where each coset partitions the elements of .[4] A prerequisite for this construction is that must be a normal subgroup of , meaning that for all and , the conjugate .[4] Normality ensures that the set of cosets forms a group under the induced operation defined by for .[3] This operation is well-defined, independent of the choice of representatives and , because is normal.[4] The quotient satisfies the group axioms: the identity element is the coset itself (corresponding to the identity in ); the inverse of a coset is ; and associativity follows from that in .[3] If and are finite, the order of the quotient group is given by , as established by Lagrange's theorem.[3]Cosets and Normal Subgroups

In group theory, given a group and a subgroup , the left coset of generated by an element is the set .[5] Similarly, the right coset is .[5] These cosets represent translates of the subgroup within , and in general, left and right cosets may differ when is non-abelian. The collection of all left cosets of in forms a partition of , meaning the cosets are disjoint and their union is .[6] The same holds for right cosets.[6] Moreover, every left coset and every right coset has the same cardinality as , so and for all .[6] This equality follows from the bijection between and , which preserves the group structure. To endow the set of cosets with a group operation, define multiplication of left cosets by . For this operation to be well-defined—independent of the choice of representatives and — must be a normal subgroup of .[7] Specifically, if and , then and for some , so . The product equals if and only if , or equivalently, for some . This holds for all such elements precisely when left and right cosets coincide, i.e., when is normal.[7] A subgroup is normal if and only if every left coset equals the corresponding right coset, so for all .[8] Equivalently, is normal if it is invariant under conjugation by elements of , meaning for all .[8] These criteria ensure the coset multiplication is associative and forms a group. For an illustration of a non-normal subgroup, consider the symmetric group on three letters and the subgroup . To check normality, compute the conjugate . Since and , the conjugate is , which is not contained in . Thus, is not normal in .[9] This failure implies that coset multiplication would not be well-defined for .Motivation and Construction

Origin of the Term "Quotient"

The term "quotient group" was introduced by William Burnside in his seminal 1897 textbook Theory of Groups of Finite Order, marking the first systematic use of the phrase in the context of abstract group theory.[10] Earlier, in 1893, Arthur Cayley had referred to the structure G/H as a "quotient" without fully specifying the term for the group itself. This naming convention emerged in the late 19th century, paralleling Richard Dedekind's earlier introduction of quotient rings in 1871, where he developed the concept to handle factorization in rings of algebraic integers via ideals.[11] Dedekind's work on quotient structures provided a foundational analogy that influenced group theorists, as both constructions involve dividing an algebraic object by a substructure to form a new entity. The choice of "quotient" reflects a direct analogy to division in arithmetic, particularly integer division. Just as dividing the integers ℤ by the subgroup nℤ yields the cyclic group ℤ/nℤ of order n, the quotient group G/N of a group G by a normal subgroup N has order |G|/|N| when finite, effectively "dividing out" the size of N to obtain a smaller group that captures the structure of G modulo N. This mirrors how remainders in division classify integers into equivalence classes, providing an intuitive bridge from elementary number theory to abstract algebra. Conceptually, forming the quotient group "factors out" the subgroup N by collapsing its elements to the identity, similar to how group presentations mod out by relations to define new groups. This process simplifies the original group by ignoring internal symmetries imposed by N, allowing focus on the coarser structure. In set-theoretic terms, the quotient arises from identifying elements that differ by elements of N, partitioning G into equivalence classes known as cosets, much like quotient sets in general equivalence relations.[12] This identification preserves the group operation on the cosets, yielding a group that encodes G's behavior up to translation by N.Homomorphism Theorem Connection

The first isomorphism theorem establishes a fundamental connection between group homomorphisms and quotient groups. Specifically, if is a group homomorphism, then , where denotes the kernel of .[13] If is surjective, this simplifies to .[14] A key prerequisite is that the kernel must be a normal subgroup of . To see this, let and take any , . Then , where is the identity in , so . Thus, for all , confirming normality.[14] The proof of the theorem proceeds by constructing an induced map from the quotient to the image. Define by . This is well-defined because if , then , so implies . Moreover, is a homomorphism since . It is injective because implies , so and . Surjectivity follows from the definition of the image. Hence, is an isomorphism.[13] This theorem also explains the construction of quotient groups via projections. For any normal subgroup , the canonical projection defined by is a surjective homomorphism with . Applying the first isomorphism theorem yields , which is tautological but confirms the setup.[15] The theorem motivates quotient groups as a universal mechanism for factoring out normal subgroups: any homomorphism vanishing on factors uniquely through the projection , providing a canonical way to "mod out" by .[13]Basic Examples

Integers Modulo n

The additive group of integers, denoted , forms an infinite abelian group under addition, with the subgroup consisting of all integer multiples of a fixed positive integer . Since is abelian, every subgroup is normal, making a normal subgroup of .[3] The cosets of in are the sets of the form for integers , each representing a distinct residue class modulo . These cosets partition and form the quotient group , where the group operation is defined by . This operation is well-defined because if and , then . The quotient group is isomorphic to the cyclic group of order , generated by the coset .[16] For a concrete illustration, consider . The cosets are:- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .