Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Modular group

View on Wikipedia| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

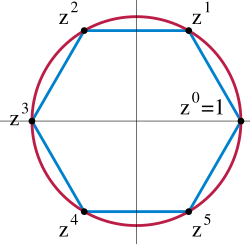

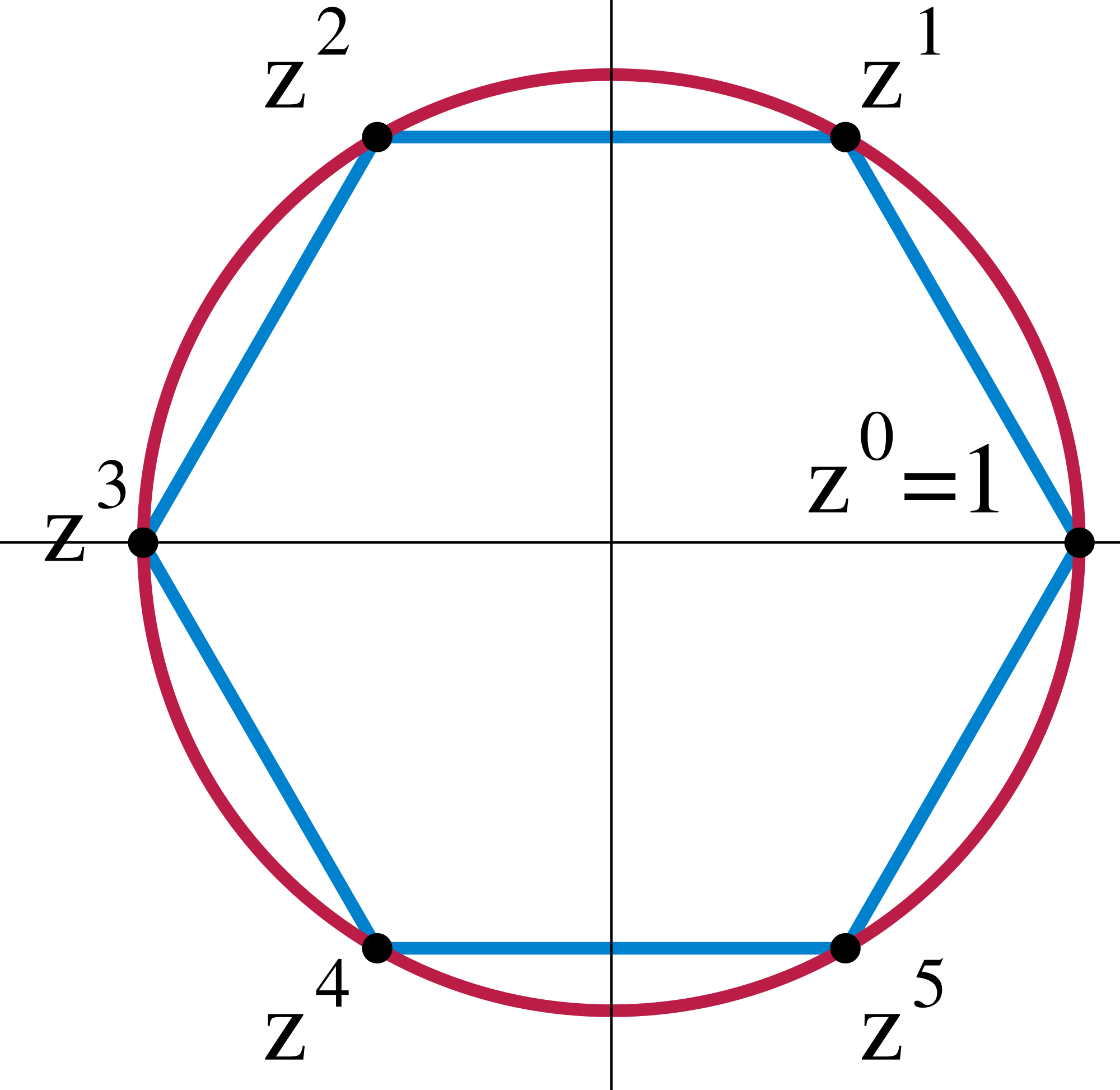

In mathematics, the modular group is the projective special linear group of matrices with integer coefficients and determinant , such that the matrices and are identified. The modular group acts on the upper-half of the complex plane by linear fractional transformations. The name "modular group" comes from the relation to moduli spaces, and not from modular arithmetic.

Definition

[edit]The modular group Γ is the group of fractional linear transformations of the complex upper half-plane, which have the form

where are integers, and . The group operation is function composition.

This group of transformations is isomorphic to the projective special linear group , which is the quotient of the 2-dimensional special linear group by its center . In other words, consists of all matrices

where are integers, , and pairs of matrices and are considered to be identical. The group operation is usual matrix multiplication.

Some authors define the modular group to be , and still others define the modular group to be the larger group .

Some mathematical relations require the consideration of the group of matrices with determinant plus or minus one. ( is a subgroup of this group.) Similarly, is the quotient group .

Since all matrices with determinant 1 are symplectic matrices, then , the symplectic group of matrices.

Finding elements

[edit]To find an explicit matrix

in , begin with two coprime integers , and solve the determinant equation .[a]

For example, if then the determinant equation reads

then taking and gives . Hence

is a matrix. Then, using the projection, these matrices define elements in .

Number-theoretic properties

[edit]The unit determinant of

implies that the fractions a/b, a/c, c/d, b/d are all irreducible, that is having no common factors (provided the denominators are non-zero, of course). More generally, if p/q is an irreducible fraction, then

is also irreducible (again, provided the denominator be non-zero). Any pair of irreducible fractions can be connected in this way; that is, for any pair p/q and r/s of irreducible fractions, there exist elements

such that

Elements of the modular group provide a symmetry on the two-dimensional lattice. Let ω1 and ω2 be two complex numbers whose ratio is not real. Then the set of points

is a lattice of parallelograms on the plane. A different pair of vectors α1 and α2 will generate exactly the same lattice if and only if

for some matrix in GL(2, Z). It is for this reason that doubly periodic functions, such as elliptic functions, possess a modular group symmetry.

The action of the modular group on the rational numbers can most easily be understood by envisioning a square grid, with grid point (p, q) corresponding to the fraction p/q (see Euclid's orchard). An irreducible fraction is one that is visible from the origin; the action of the modular group on a fraction never takes a visible (irreducible) to a hidden (reducible) one, and vice versa.

Note that any member of the modular group maps the projectively extended real line one-to-one to itself, and furthermore bijectively maps the projectively extended rational line (the rationals with infinity) to itself, the irrationals to the irrationals, the transcendental numbers to the transcendental numbers, the non-real numbers to the non-real numbers, the upper half-plane to the upper half-plane, et cetera.

If pn−1/qn−1 and pn/qn are two successive convergents of a continued fraction, then the matrix

belongs to GL(2, Z). In particular, if bc − ad = 1 for positive integers a, b, c, d with a < b and c < d then a/b and c/d will be neighbours in the Farey sequence of order max(b, d). Important special cases of continued fraction convergents include the Fibonacci numbers and solutions to Pell's equation. In both cases, the numbers can be arranged to form a semigroup subset of the modular group.

Group-theoretic properties

[edit]Presentation

[edit]The modular group can be shown to be generated by the two transformations

so that every element in the modular group can be represented (in a non-unique way) by the composition of powers of S and T. Geometrically, S represents inversion in the unit circle followed by reflection with respect to the imaginary axis, while T represents a unit translation to the right.

The generators S and T obey the relations S2 = 1 and (ST)3 = 1. It can be shown [1] that these are a complete set of relations, so the modular group has the presentation:

This presentation describes the modular group as the rotational triangle group D(2, 3, ∞) (infinity as there is no relation on T), and it thus maps onto all triangle groups (2, 3, n) by adding the relation Tn = 1, which occurs for instance in the congruence subgroup Γ(n).

Using the generators S and ST instead of S and T, this shows that the modular group is isomorphic to the free product of the cyclic groups C2 and C3:

-

The action of T : z ↦ z + 1 on H

-

The action of S : z ↦ −1/z on H

Braid group

[edit]

The braid group B3 is the universal central extension of the modular group, with these sitting as lattices inside the (topological) universal covering group SL2(R) → PSL2(R). Further, the modular group has a trivial center, and thus the modular group is isomorphic to the quotient group of B3 modulo its center; equivalently, to the group of inner automorphisms of B3.

The braid group B3 in turn is isomorphic to the knot group of the trefoil knot.

Quotients

[edit]The quotients by congruence subgroups are of significant interest.

Other important quotients are the (2, 3, n) triangle groups, which correspond geometrically to descending to a cylinder, quotienting the x coordinate modulo n, as Tn = (z ↦ z + n). (2, 3, 5) is the group of icosahedral symmetry, and the (2, 3, 7) triangle group (and associated tiling) is the cover for all Hurwitz surfaces.

Presenting as a matrix group

[edit]The group can be generated by the two matrices[2]

since

The projection turns these matrices into generators of , with relations similar to the group presentation.

Relationship to hyperbolic geometry

[edit]The modular group is important because it forms a subgroup of the group of isometries of the hyperbolic plane. If we consider the upper half-plane model H of hyperbolic plane geometry, then the group of all orientation-preserving isometries of H consists of all Möbius transformations of the form

where a, b, c, d are real numbers. In terms of projective coordinates, the group PSL(2, R) acts on the upper half-plane H by projectivity:

This action is faithful. Since PSL(2, Z) is a subgroup of PSL(2, R), the modular group is a subgroup of the group of orientation-preserving isometries of H.[3]

Tessellation of the hyperbolic plane

[edit]

The modular group Γ acts on as a discrete subgroup of , that is, for each z in we can find a neighbourhood of z which does not contain any other element of the orbit of z. This also means that we can construct fundamental domains, which (roughly) contain exactly one representative from the orbit of every z in H. (Care is needed on the boundary of the domain.)

There are many ways of constructing a fundamental domain, but a common choice is the region

bounded by the vertical lines Re(z) = 1/2 and Re(z) = −1/2, and the circle |z| = 1. This region is a hyperbolic triangle. It has vertices at 1/2 + i√3/2 and −1/2 + i√3/2, where the angle between its sides is π/3, and a third vertex at infinity, where the angle between its sides is 0.

There is a strong connection between the modular group and elliptic curves. Each point in the upper half-plane gives an elliptic curve, namely the quotient of by the lattice generated by 1 and . Two points in the upper half-plane give isomorphic elliptic curves if and only if they are related by a transformation in the modular group. Thus, the quotient of the upper half-plane by the action of the modular group is the so-called moduli space of elliptic curves: a space whose points describe isomorphism classes of elliptic curves. This is often visualized as the fundamental domain described above, with some points on its boundary identified.

The modular group and its subgroups are also a source of interesting tilings of the hyperbolic plane. By transforming this fundamental domain in turn by each of the elements of the modular group, a regular tessellation of the hyperbolic plane by congruent hyperbolic triangles known as the V6.6.∞ Infinite-order triangular tiling is created. Note that each such triangle has one vertex either at infinity or on the real axis Im(z) = 0.

This tiling can be extended to the Poincaré disk, where every hyperbolic triangle has one vertex on the boundary of the disk. The tiling of the Poincaré disk is given in a natural way by the J-invariant, which is invariant under the modular group, and attains every complex number once in each triangle of these regions.

This tessellation can be refined slightly, dividing each region into two halves (conventionally colored black and white), by adding an orientation-reversing map; the colors then correspond to orientation of the domain. Adding in (x, y) ↦ (−x, y) and taking the right half of the region R (where Re(z) ≥ 0) yields the usual tessellation. This tessellation first appears in print in (Klein & 1878/79a),[4] where it is credited to Richard Dedekind, in reference to (Dedekind 1877).[4][5]

The map of groups (2, 3, ∞) → (2, 3, n) (from modular group to triangle group) can be visualized in terms of this tiling (yielding a tiling on the modular curve), as depicted in the video at right.

| Paracompact uniform tilings in [∞,3] family | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [∞,3], (*∞32) | [∞,3]+ (∞32) |

[1+,∞,3] (*∞33) |

[∞,3+] (3*∞) | |||||||

= |

= |

= |

= | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| {∞,3} | t{∞,3} | r{∞,3} | t{3,∞} | {3,∞} | rr{∞,3} | tr{∞,3} | sr{∞,3} | h{∞,3} | h2{∞,3} | s{3,∞} |

| Uniform duals | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| V∞3 | V3.∞.∞ | V(3.∞)2 | V6.6.∞ | V3∞ | V4.3.4.∞ | V4.6.∞ | V3.3.3.3.∞ | V(3.∞)3 | V3.3.3.3.3.∞ | |

Congruence subgroups

[edit]Important subgroups of the modular group Γ, called congruence subgroups, are given by imposing congruence relations on the associated matrices.

There is a natural homomorphism SL(2, Z) → SL(2, Z/NZ) given by reducing the entries modulo N. This induces a homomorphism on the modular group PSL(2, Z) → PSL(2, Z/NZ). The kernel of this homomorphism is called the principal congruence subgroup of level N, denoted Γ(N). We have the following short exact sequence:

Being the kernel of a homomorphism Γ(N) is a normal subgroup of the modular group Γ. The group Γ(N) is given as the set of all modular transformations

for which a ≡ d ≡ ±1 (mod N) and b ≡ c ≡ 0 (mod N).

It is easy to show that the trace of a matrix representing an element of Γ(N) cannot be −1, 0, or 1, so these subgroups are torsion-free groups. (There are other torsion-free subgroups.)

The principal congruence subgroup of level 2, Γ(2), is also called the modular group Λ. Since PSL(2, Z/2Z) is isomorphic to S3, Λ is a subgroup of index 6. The group Λ consists of all modular transformations for which a and d are odd and b and c are even.

Another important family of congruence subgroups are the modular group Γ0(N) defined as the set of all modular transformations for which c ≡ 0 (mod N), or equivalently, as the subgroup whose matrices become upper triangular upon reduction modulo N. Note that Γ(N) is a subgroup of Γ0(N). The modular curves associated with these groups are an aspect of monstrous moonshine – for a prime number p, the modular curve of the normalizer is genus zero if and only if p divides the order of the monster group, or equivalently, if p is a supersingular prime.

Dyadic monoid

[edit]One important subset of the modular group is the dyadic monoid, which is the monoid of all strings of the form STn1STn2STn3... for positive integers ni. This monoid occurs naturally in the study of fractal curves, and describes the self-similarity symmetries of the Cantor function, Minkowski's question mark function, and the Koch snowflake, each being a special case of the general de Rham curve. The monoid also has higher-dimensional linear representations; for example, the N = 3 representation can be understood to describe the self-symmetry of the blancmange curve.

Maps of the torus

[edit]The group GL(2, Z) is the linear maps preserving the standard lattice Z2, and SL(2, Z) is the orientation-preserving maps preserving this lattice; they thus descend to self-homeomorphisms of the torus (SL mapping to orientation-preserving maps), and in fact map isomorphically to the (extended) mapping class group of the torus, meaning that every self-homeomorphism of the torus is isotopic to a map of this form. The algebraic properties of a matrix as an element of GL(2, Z) correspond to the dynamics of the induced map of the torus.

Hecke groups

[edit]The modular group can be generalized to the Hecke groups, named for Erich Hecke, and defined as follows.[7]

The Hecke group Hq with q ≥ 3, is the discrete group generated by

where λq = 2 cos π/q. For small values of q ≥ 3, one has:

The modular group Γ is isomorphic to H3 and they share properties and applications – for example, just as one has the free product of cyclic groups

more generally one has

which corresponds to the triangle group (2, q, ∞). There is similarly a notion of principal congruence subgroups associated to principal ideals in Z[λ].

History

[edit]The modular group and its subgroups were first studied in detail by Richard Dedekind and by Felix Klein as part of his Erlangen programme in the 1870s. However, the closely related elliptic functions were studied by Joseph Louis Lagrange in 1785, and further results on elliptic functions were published by Carl Gustav Jakob Jacobi and Niels Henrik Abel in 1827.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Notice the determinant equation forces to be coprime, since otherwise there would be a factor such that and , hence would have no integer solutions.

References

[edit]- ^ Alperin, Roger C. (April 1993). "PSL2(Z) = Z2 ∗ Z3". Amer. Math. Monthly. 100 (4): 385–386. doi:10.2307/2324963. JSTOR 2324963.

- ^ Conrad, Keith. "SL(2,Z)" (PDF).

- ^ McCreary, Paul R.; Murphy, Teri Jo; Carter, Christian. "The Modular Group" (PDF). The Mathematica Journal. 9 (3).

- ^ a b Le Bruyn, Lieven (22 April 2008), Dedekind or Klein?

- ^ Stillwell, John (January 2001). "Modular Miracles". The American Mathematical Monthly. 108 (1): 70–76. doi:10.2307/2695682. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 2695682.

- ^ Westendorp, Gerard. "Platonic tessellations of Riemann surfaces". westy31.nl.

- ^ Rosenberger, Gerhard; Fine, Benjamin; Gaglione, Anthony M.; Spellman, Dennis (2006). Combinatorial Group Theory, Discrete Groups, and Number Theory. American Mathematical Society. p. 65. ISBN 9780821839850.

- Apostol, Tom M. (1990). Modular Functions and Dirichlet Series in Number Theory (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ch. 2. ISBN 0-387-97127-0.

- Klein, Felix (1878–1879), "Über die Transformation der elliptischen Funktionen und die Auflösung der Gleichungen fünften Grades (On the transformation of elliptic functions and ...)", Math. Annalen, 14 (1): 13–75, doi:10.1007/BF02297507, S2CID 121056952, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 3 June 2010

- Dedekind, Richard (September 1877), "Schreiben an Herrn Borchardt über die Theorie der elliptische Modul-Functionen", Crelle's Journal, 83: 265–292.

![{\displaystyle [z,\ 1]{\begin{pmatrix}a&c\\b&d\end{pmatrix}}\,=\,[az+b,\ cz+d]\,\thicksim \,\left[{\frac {az+b}{cz+d}},\ 1\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/786774df43d89ded3a9c6d135dc0fae20bd518ba)