Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

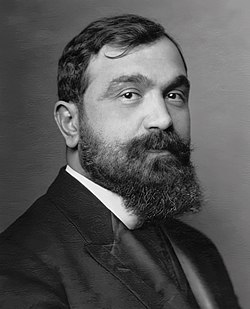

Fan Noli

View on Wikipedia

Theofan Stilian Noli, known as Fan Noli (6 January 1882 – 13 March 1965), was an Albanian-American writer, scholar, diplomat, politician, historian, orator, bishop, and founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church and the Albanian Orthodox Archdiocese in America who served as Prime Minister and regent of Albania in 1924 during the June Revolution.[2]

Key Information

Fan Noli is venerated in Albania as a champion of literature, history, theology, diplomacy, journalism, music, national unity and ecumenism. He played an important role in the consolidation of Albanian as the national language of Albania with numerous translations of world literature masterpieces.[3] He also wrote extensively in English: as a scholar and author of a series of publications on Skanderbeg, Shakespeare, Beethoven, religious texts and translations.[3] He produced a translation of the New Testament in English, The New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ from the approved Greek text of the Church of Constantinople and the Church of Greece, published in 1961.

Noli earned degrees at Harvard[1] (1912), the New England Conservatory of Music (1938), and finally his Ph.D. from Boston University (1945).[4][5] He was ordained a priest in 1908, establishing thereby the Albanian Church and elevating the Albanian language to ecclesiastic use. He briefly resided in Albania after the 1912 declaration of independence. After World War I, Noli led the diplomatic efforts for the reunification of Albania and received the support of US President Woodrow Wilson. Later he pursued a diplomatic-political career in Albania, successfully leading the Albanian bid for membership in the League of Nations.

A respected figure who remained critical of corruption and injustice in the Albanian government, Fan Noli was asked to lead the 1924 June Revolution. He then served as prime minister until his revolutionary government was overthrown by Ahmet Zogu. He was exiled to Italy and permanently settled in the United States in the 1930s, acquiring US citizenship and agreeing to end his political involvement. He spent the rest of his life as an academician, religious leader, and writer.

Background

[edit]Fan Noli was born Theofanis Stylianos Mavromatis 1882 in İbriktepe, a small village situated in the Thracian Ottoman Vilayet of Adrianople (modern Turkey) which was originally settled by Albanians from Qyteza. Qyteza is a village in the County of Kolonjë, and İbriktepe was known to the local townspeople as Qyteza at the time.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] He was an Albanian[15][16] of the Eastern Orthodox faith. Noli was a descendant of these Orthodox Christian Albanian settlers who fled what is today southern Albania and resettled in Thrace in areas that had been depopulated due to regional conflicts.[17] During his youth, Noli received his education from Greek elementary and secondary schools.[5] As a young man, Noli wandered throughout the Mediterranean Basin, living in Athens in Greece, Alexandria in Egypt and Odessa in Russia, and supported himself as an actor and translator. As well as his native Albanian, he spoke many languages such as Greek, English, French, Turkish, and Arabic.[18] He went to Athens to become a teacher, and there he used the name Theofanis Mavromattis. Thereafter he went as a teacher or a member of a theater in the Albanian diaspora in Egypt, where he followed the Albanian national program.[19] Through his contacts with the Albanian expatriate movement, he became an ardent supporter of his country's nationalist movement and moved to the United States in 1906.[20] He first worked in Buffalo, New York, in a lumber mill and then moved to Boston, Massachusetts, and worked as an operator on a machine which stamped labels on cans.[18] The Young Turks (CUP) had a hostile view of Albanian leaders such as Fan Noli who were doing political activities with the assistance of outside powers.[21]

Hudson Incident

[edit]The earliest Orthodox Christian Albanian immigrants to Boston were communicants of the Greek Orthodox Church, the leadership of which was vehemently opposed to the Albanian nationalist cause. When Kristaq Dishnica, a young factory worker who had died of influenza, was refused burial on the grounds that, as an Orthodox Christian who identified as an Albanian, he was therefore automatically excommunicated from the Greek Orthodox Church, Fan Noli and a group of Albanian émigrés in New England set about laying the groundwork for an independent, autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church. The event, which came to be known as the Hudson Incident, was a seminal moment in the establishment of an independent Albanian Orthodox Christian religious consciousness.[22][5] Noli, the new church's first clergyman, was ordained as a priest in 1908 by Archbishop Platon (Rozhdestvensky) of the Russian Church in the United States.[18][5][23] By achieving Patriarchal recognition for the autocephaly of the Albanian Orthodox Church and the full translation of the Orthodox liturgy from the original Greek text into Tosk Albanian, Noli aimed to peacefully neutralize and dismantle the ideological platform of Greek irredentism promoted by reactionaries within the Orthodox Church in Albania and to defend the right of Orthodox Christian Albanians to coexist with their Greek neighbors in a secular Republic immune to the sectarian Megali Idea.[24] Noli was a staunch supporter of Albanian patriotic unity and a separation of religion from the state and moreover, considered it important for religious office to be held by clergy fluent in Albanian and possessing Albanian citizenship.[25]

Political and religious activities

[edit]

In 1908, Noli began studying at Harvard, completing his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1912.[26] During April 1912 Vatra (Hearth) an Albanian American diaspora organisation was founded with Noli and Faik Konica serving as its leaders and advocating for Albanian sociopolitical self determination with the Ottoman Empire.[27] He returned to Europe to promote Albanian independence, setting foot in Albania for the first time in 1913.[26] Noli returned to the United States during World War I, serving as head of the Vatra organization, which effectively made him leader of the Albanian diaspora.[26] His diplomatic efforts in the United States and Geneva won the support of President Woodrow Wilson for an independent Albania and, in 1920, earned the new national membership in the fledgling League of Nations.[28] Though Albania had already declared its independence in 1912, membership in the League of Nations provided the country with the international recognition it had failed to obtain until then.[29]

In 1921, Noli entered the Albanian Parliament as a representative of the liberal pro-British "People's Party" (Albanian: Partia e Popullit), the chief liberal movement in the country.[30] The other parties were the conservative pro-Italian "Progressive Party" (Albanian: Partia Përparimtare) founded by Mehdi Frashëri and led by Ahmet Zogu, and "Popular Party" (Albanian: Partia Popullore) of Xhafer Ypi. The conservatives of Zogu would dominate the political scene.[31][32] A Congress of Berat in 1922 was convened to formally lay the foundations of an Albanian Orthodox Church which consecrated Fan Noli as Bishop of Korçë and primate of all Albania while the establishment of the church was seen as important for maintaining Albanian national unity.[22][33]

Noli served briefly as Foreign Minister in the government of Xhafer Ypi.[34] This was a period of intense turmoil in the country between the liberals and the conservatives.[35] After a botched assassination attempt against Zogu, the conservatives revenged themselves by assassinating another popular liberal politician, Avni Rustemi.[36] Noli's speech at Rustemi's funeral was so powerful that liberal supporters rose up against Zogu and forced him to flee to Yugoslavia (March 1924).[37] Zogu was succeeded briefly by his father-in-law, Shefqet Vërlaci, and by the liberal politician Iliaz Vrioni; Noli was named prime minister and regent on 16 June 1924.[38]

Downfall and exile

[edit]

Despite his efforts to reform the country, Noli's "Twenty Point Program" was unpopular, and his government was overthrown by groups loyal to Zogu on Christmas Eve of that year.[39] Two weeks later, Zogu returned to Albania, and Noli fled to Italy under sentence of death.[40]

Conscious of his fragile position, Zogu took drastic measures to consolidate his return to power. By the end of winter, two of the main leaders of the opposition, Bajram Curri and Luigj Gurakuqi, were assassinated, while others were imprisoned.

Noli founded the "National Committee" (Albanian: Komiteti Nacional Revolucionar) also known as KONARE in Vienna. The committee published the periodical called "National Freedom" (Albanian: Liria Kombëtare). Some of the early Albanian communists as Halim Xhelo or Riza Cerova would start their publishing activities here. The committee aimed in overthrowing Zogu and his cast and restoring democracy. Despite the efforts, the committee's access and influence in Albania would be limited. With the intervention of Kosta Boshnjaku, an old communist and KONARE member, the organization would receive unconditioned monetary support from the Comintern. Also Noli and Boshnjaku would make possible for exile members of the Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo (outlawed by Zogu) to get the same financial support.[41]

In 1928, KONARE changed its name to "Committee of National Liberation" (Albanian: Komiteti i Çlirimit Kombëtar). Meanwhile, in Albania, after three years of republican regime, the "National Council" declared Albania a Constitutional Monarchy, and Ahmet Zogu became king.[42] Noli moved back to the United States in 1932 and formed a republican opposition to Zogu, who had since proclaimed himself "King Zog I". Over the next years, he continued his education, studying and later teaching Byzantine music, and continued developing and promoting the autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church he had helped to found.

After the war, Noli established some ties with the communist government of Enver Hoxha, which seized power in 1944. He unsuccessfully urged the U.S. government to recognize the regime, but Hoxha's increasing persecution of all religions prevented Noli's church from maintaining ties with the Orthodox hierarchy in Albania. Despite the Hoxha regime's anticlerical bent, Noli's ardent Albanian nationalism brought the bishop to the attention of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI's Boston office kept the bishop under investigation for more than a decade with no final outcome to the probe.

In 1945, Fan S. Noli received a doctor's degree (Ph.D.) in history from Boston University,[5] writing a dissertation on Skanderbeg.[43][44] In the meantime, he also conducted research at Boston University Music Department, publishing a biography on Ludwig van Beethoven. He also composed a one-movement symphony called Scanderbeg in 1947. Toward the end of his life, Noli retired to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where he died in 1965.

Fan Noli is interred in Forest Hills Cemetery, situated in the southern part of Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood.

The Albanian Orthodox Archdiocese in America founded by Noli went on to join the Orthodox Church in America, today led by Metropolitan Tikhon Mollard as the Albanian Archdiocese. Until recently overseen by Archbishop Nikon of Boston and the Very Reverend Arthur E. Liolin, the Albanian Archdiocese of the Orthodox Church in America is currently headed by Interim Chancellor Igumen Nikodhim Preston. It consists of eleven urban and suburban parishes situated primarily in the urban centers of the Northeastern United States and the Midwestern United States. The Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Albania, which Noli served in Albania, is presided over by Archbishop Anastasios of Albania, headquartered in the Albanian capital city of Tirana and a member of the World Council of Churches. In addition, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America administers two Albanian Orthodox parishes in Boston and Chicago. All Albanian Orthodox parishes are today in full communion with one another and with the broader worldwide body of the Orthodox Church and fully recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Writing in his diary two days after Noli's death, Albanian leader Enver Hoxha gave his analysis of Noli's work:[45]

As we are informed, Fan S. Noli died from an operation done last week in which, because of his age, he did not survive. A cerebral hemorrhage caused a quick death. Noli was one of the prominent political and literary figures of the beginning of this century. The balance sheet of his life was positive ... Fan Noli today enjoys a great popularity in our country, deserved as a literary translator and music critic. He was a prominent promoter of the Albanian language. His original works and translations, especially of Shakespeare, of Omar Khayyám and Blasco Ibáñez, are immortal. But especially his anti-Zogist, anti-feudal elegies and poems are beautiful jewels that have inspired and will inspire our youth, especially in creativity. He was also respected as a realistic politician, as a revolutionary democrat in ideology and politics. The Party has assessed the figure of Noli. As is deserved, we have had a patriotic duty to point out the really great merits of his in literature, the history of the arts, and his merits and weaknesses in politics. I think we will do our best in bringing his body to Albania, as this distinguished son of the people, the revolutionary patriot, deserves to bask in his homeland, which he loved and fought for his entire life.

— Enver Hoxha

Fan S. Noli is depicted on the obverse of the Albanian 100 lekë banknote issued in 1996. It remained in use until 2008 when it was replaced by a coin.[46]

Poems

[edit]The following poems were written by Fan Noli:

- Hymni i Flamurit

- Thomsoni dhe Kuçedra

- Jepni për Nënën

- Moisiu në mal

- Marshi i Krishtit

- Krishti me kamçikun

- Shën Pjetrin në Mangall

- Marshi i Barabbajt

- Marshi i Kryqësmit

- Kirenari

- Kryqësmi

- Kënga e Salep-Sulltanit

- Syrgjyn-vdekur

- Shpell' e Dragobisë

- Rent, or Marathonomak!

- Anës lumejve

- Plak, topall dhe ashik

- Sofokliu

- Tallja përpara Kryqit

- Sulltani dhe kabineti

- Saga e Sermajesë

- Lidhje e paçkëputur

- Çepelitja

- Vdekja e Sulltanit

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Thernstrom 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Brisku, Adrian (2020). "Renegotiating the Empire, Forging the Nation-State: The Albanian Case through the Political Economic Thought of Ismail Qemali, Fan Noli, and Luigj Gurakuqi, c. 1890–1920s". Nationalities Papers. 48 (1): 158–174. doi:10.1017/nps.2018.52. ISSN 0090-5992. S2CID 211344809.

- ^ a b Spahiu & Mjeku 2009.

- ^ p. 175. William Paul. 2003. English Language Bible Translators. Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland and Co.

- ^ a b c d e Skendi 1967, p. 162.

- ^ Curtis 1994, p. 465: "Born Theophanus Stylianos Mavromatis in Ibrik-Tepe, an Albanian village, then part of the Ottoman Empire, Fan Stylian Noli was educated in the Greek Gymnasium of Edirne (Adrianople)."

- ^ Stavrou 1996, p. 40: "Fan Noli was born Theofanis Stylianou Mavromates in the village of Qytezë of the Vilayet of Adrianople, in Ottoman Thrace, in 1882."

- ^ The Central European Observer 1943, p. 63: "But Theophanus Mavromatis, which was Fan Noli's original name, came in 1900, after assisting in an ironmonger's shop, to Adrianople, where the good teachers gave him an education."

- ^ Baerlein 1968, p. 76: "... year 1900 his name was Theophanus Mavromatis, which is Greek."

- ^ Free Europe 1941, p. 278: "The one personage as to whom Mr. Robinson seems to be misinformed is Bishop Fan Noli, who has for many years lived in the United States and whom Mr. Robinson probably did not meet ... He says that this former Premier was born in the south of the country, was educated at Harvard and was consecrated a Bishop in Greece. The facts are that he was born near Adrianople and that his original name was Theophanos Mavromatis, which does not necessarily imply that he was Greek."

- ^ Irénikon 1963, p. 266: "Il était connu alors sous le nom de Théophanis Mavromatis."

- ^ Ekdotiki 2000, p. 538: "158 Stylianou Theophanes Noli or Mavrommatis."

- ^ Giakoumēs, Vlassas & Hardy 1996, p. 184 "His full name was Theophanis Stylianos Mavrommatis, and he was born in Adrianople and studied in Athens and the USA. ... "

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 162. "Fan Stylian Noli was born in 1882, in Ibrik Tepe (Alb. Qytezë), an Albanian settlement south of Adrianople, in Eastern Thrace."

- ^ Brisku 2013, p. 34: "one of the most colorful Albanian politicians"

- ^ Constance J. Tarasar (1975), Orthodox America, 1794–1976: Development of the Orthodox Church in America, Syosset, N.Y: Orthodox Church in America, Department of History and Archives, p. 311, OCLC 2930511,

It was from his family that Fan Noli received a sense of identity as an Albanian

- ^ Jorgaqi 2005, p. 37. "Në disa studime greke per Trakën nuk mohohet ekzistenca e një bashkësie ortodokse shqipfolëse në prefekturën e Adrianopojës, e cila gjatë shekullit të kaluar lëvizte nga 15-25000 banorë. Madje, sipas tyre, ardhja e shqiptarëve të emigruar nga Shqipëria ka ndodhur për shkak të zbrazëtive të krijuara në Trake nga luftrat dhe shkrëtimet pas renies së Konstandinopojës."; pp. 38-39. " Ekziston dhe një gojëdhanë tjeter, por që tregohet në Shqipëri, e cila flet për një eksod masiv në drejtim të Trakës nga fshatrat e Kolonjës. Fshatarë nga Gostvishti, Perasi, Qafëzezi, Vithkuqi e Qyteza, për shkak të padrejtësive të pushtuesve dhe të fushës feudale, braktisen tokat e trye malore dhe i sistemuan në fushat e Trakës. Koha e kësaj shpërnguljeje hamendësohet të jetë e shekullit XVIII.", p. 42. "Gojëdhana që përcillej nga një brez në tjetrin, rrëfente se të parët e tyre kishin ardhur në Ibrik-Tepe nga Kolonja e Epirit. Atje ata kishin lënë Qytezën e vjetër, rrëzë malet e Rodonit...

- ^ a b c Austin 2012, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Skoulidas 2013. para. 28.

- ^ Skendi 1967, pp. 160, 162.

- ^ Hanioğlu, M. Șükrü (2001). Preparation for a Revolution: The Young Turks, 1902-1908. Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780199771110.

- ^ a b Biernat 2014, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Vickers 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 4. "Noli... Hoping to diminish Greek nationalist influence within the Orthodox Church hierarchy of Albania, Noli focused his early activities on translating the church liturgy into Albanian and the establishment of an independent Albanian Orthodox Church. The latter he considered as vital to Albania's evolution into a unified European nation."

- ^ Skendi 1967, pp. 179–180.

- ^ a b c Austin 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 453.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Brisku 2013, p. 75: "Two political groupings: the pro-British People's Party, headed by the colorful leader, Fan Noli, and the pro—Italian Progressive Party, led by Mehdi Frashéri, came to dominate the political scene."

- ^ Bogdani & Loughlin 2009, p. 122: "The first Albanian political parties, in the western meaning of the word, appeared in the early 1920s, the most prominent being: the Progressive Party led by Ahmet Zogu, the People's Party led by Fan Noli, and the Popular Party led by Xhafer Ypi."

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 31, 95.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 39–40, 45–46.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 46–47, 51, 159.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 59–74, 80–82, 146–150.

- ^ Austin 2012, pp. 152–155.

- ^ Vllamasi & Verli 2000, "Një pjesë me rëndësi e emigrantëve, me inisiativën dhe ndërmjetësinë e Koço Boshnjakut, u muarrën vesh me "Cominternin", si grup, me emër "KONARE" (Komiteti Revolucionar Kombëtar), për t'u ndihmuar pa kusht gjatë aktivitetit të tyre nacional, ashtu siç janë ndihmuar edhe kombet e tjerë të vegjël, që ndodheshin nën zgjedhë të imperialistëve, për liri e për pavarësi. Përveç kësaj pjese, edhe emigrantët kosovarë irredentistë, të grupuar e të organizuar nën emrin "Komiteti i Kosovës", si grup, u ndihmuan edhe ata nga "Cominterni"."

- ^ Ersoy, Górny & Kechriotis 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Austin 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Noli, Fan Stylian (21 February 2018). "George Castrioti Scanderbeg (1405-1468)". Retrieved 21 February 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hoxha, Enver (1989). "Ditar: 1965". Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House. pp. 172–174.

- ^ Bank of Albania (2004–2012). "Banknotes Withdrawn from Circulation". Bank of Albania. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

Sources

[edit]- Athene (1944). Athene. Chicago, IL: Athene Enterprises, Incorporated.

- Austin, Robert Clegg (2012). Founding a Balkan State: Albania's Experiment With Democracy, 1920–1925. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4435-9.

- Baerlein, Henry (1968). Southern Albania: Under the Acroceraunian Mountains. Chicago: Argonaut.

- Biernat, Agata (2014). "Albania and Albanian émigrés in the United States before World War II". In Mazurkiewicz, Anna (ed.). East Central Europe in Exile Volume 1: Transatlantic Migrations. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 9–22. ISBN 9781443868914.

- Bogdani, Mirela; Loughlin, John (2009) [2007]. Albania and the European Union: The Tumultuous Journey Towards Integration and Accession. Library of European Studies. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-308-7.

- Binder, David (2004). "Vlachs: A Peaceful Balkan People" (PDF). Mediterranean Quarterly. 15 (4). Duke University Press: 115–124. doi:10.1215/10474552-15-4-115. S2CID 154461762.

- Brisku, Adrian (2013). Bittersweet Europe: Albanian and Georgian Discourses on Europe, 1878–2008. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-985-5.

- Curtis, Ference Gregory (1994). Chronology of 20th-century Eastern European History. Detroit, MI: Gale Research, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8103-8879-6.

- Ekdotiki, Athenon (2000). The Splendour of Orthodoxy: 2000 years history, monuments, art. Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe. Vol. 3. Budapest and New York: Ekdotiki Athenon. ISBN 978-960-213-398-9.

- Ersoy, Ahmet; Górny, Maciej; Kechriotis, Vangelis (2010). Modernism: Representations of National Culture. Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe. Vol. 3. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-7326-64-6.

- Free Europe (1941). Free Europe: Fortnightly Review of International Affairs (Volumes 4–5). London: Free Europe.

- Giakoumēs, Geōrgios K.; Vlassas, Grēgorēs; Hardy, David A. (1996). Monuments of Orthodoxy in Albania. Doukas School. ISBN 978-960-7203-09-0.

- Irénikon (1963). Irénikon (Volume 36) (in French). Amay, Belgium: Monastère Bénédictin.

- Jorgaqi, Nasho (2005). Jeta e Fan S. Nolit: Vëllimi 1. 1882–1924 [The life of Fan S. Noli: Volume 1. 1882–1924]. Tiranë: Ombra GVG. ISBN 9789994384303.

- Naval Society (1928). The Naval Review (Volume 16). London: Naval Society.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400847761.

- Skoulidas, Elias (2013). "The Albanian Greek-Orthodox Intellectuals: Aspects of their Discourse between Albanian and Greek National Narratives (late 19th - early 20th centuries)". Hronos. 7. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Spahiu, Avni; Mjeku, Getoar (2009). Fan Noli's American Years: Notes on a Great Albanian American. Houston, TX: Jalifat Group. ISBN 978-0-9767140-2-6.

- Stavrou, Nikolaos A. (1996). "Albanian Communism and the 'Red Bishop'". Mediterranean Quarterly. 7 (2): 32–59.

- The Central European Observer (1943). The Central European Observer (Volume 20). Prague: "Orbis" Publishing Company.

- Thernstrom, Stephan (1980). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-37512-3.

- Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: a modern history. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9780857736550.

- Vllamasi, Sejfi; Verli, Marenglen (2000). Ballafaqime Politike në Shqipëri (1897–1942): Kujtime dhe Vlerësime Historike. Tirana: Shtëpia Botuese "Neraida". ISBN 99927-713-1-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania and King Zog: Independence, Republic and Monarchy 1908–1939. London: Center for Albanian Studies. ISBN 978-1-84511-013-0.

- George Castriota Scanderbeg, by Fan Noli

- Beethoven and the French Revolution by Noli, Fan Stylian

External links

[edit]- Elsie, Robert. "Classical Authors: Fan Noli". Albanian Literature in Translation. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010.

Fan Noli

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Family Background

Fan Stilian Noli, born Theofanis Stylianos Mavromatis, entered the world on January 6, 1882, in the village of Ibrik Tepe (Albanian: Qytezë), situated south of Edirne in the Ottoman Empire's Thracian Vilayet of Adrianople, a settlement originally established by ethnic Albanians displaced from southern Albania, particularly the Korçë region.[1][8] This area, part of European Turkey at the time, hosted communities of Albanian Orthodox Christians amid a diverse Ottoman population subject to imperial policies favoring Muslim majorities and suppressing minority national aspirations.[9] Noli hailed from an ethnic Albanian family of Eastern Orthodox faith, reflecting the religious and cultural milieu of Tosk Albanian communities in the Balkans and diaspora settlements.[10] His father, Stylian Noli, originated from the Korçë area and had been exiled to Thrace due to involvement in anti-Ottoman revolutionary activities, indicative of early familial exposure to nationalist sentiments against imperial domination.[11] Limited records exist on his mother or siblings, but the family's relocation underscores the precarious position of Albanian Orthodox groups under Ottoman rule, where periodic displacements and cultural suppression fostered resilient ethnic identities.[12]Education and Immigration

Fan Stilian Noli received his early education in Greek-language schools within the Ottoman Empire, as Albanian-language instruction was prohibited by Turkish authorities. He attended elementary school locally and later pursued secondary studies at a Greek institution in Edirne (Adrianople), completing this phase around 1900 before briefly residing in Constantinople and Athens, where he engaged in occasional work amid growing Albanian nationalist sentiments.[2][13] Seeking refuge from Ottoman oppression and opportunities to advance Albanian cultural and political causes, Noli emigrated to the United States, arriving in New York on May 31, 1906. Upon arrival, he surveyed Albanian immigrant communities, worked briefly in manual labor such as wood-cutting in Buffalo, and contributed as an assistant editor to the Albanian newspaper Kombi in Boston, focusing on unifying diaspora efforts against Ottoman restrictions on Albanian identity.[14] In 1908, Noli enrolled at Harvard University, where he studied history and literature, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1912; this period marked his formal higher education and deepened his intellectual commitment to Albanian independence.[15][16]Initial Activism and the Hudson Incident

In 1906, Fan S. Noli arrived in the United States, settling in the Albanian emigrant communities of Massachusetts, where he quickly engaged in cultural and nationalist activities aimed at preserving Albanian identity amid Ottoman oppression back home.[17] He advocated for the use of the Albanian language in religious services and education, viewing linguistic suppression by dominant Greek Orthodox hierarchies as a barrier to ethnic cohesion among Orthodox Albanian immigrants, many of whom attended Greek-led parishes despite growing resentment.[1] These efforts positioned Noli as an early proponent of religious and cultural autonomy, aligning with broader Albanian independence movements by fostering unity in diaspora communities fragmented by regional loyalties and foreign ecclesiastical control.[18] The Hudson Incident of 1907 crystallized these tensions into a defining crisis for Albanian emigrants. In Hudson, Massachusetts, Kristaq Dishnica, a young Albanian factory worker and Orthodox Christian, died of influenza; his family requested a funeral service incorporating Albanian hymns and language, but the local Greek Orthodox priest refused, citing church policy against non-Greek elements and Albanian nationalist sentiments.[19] The priest withheld full rites, leading to the coffin being carried from the church without proper burial blessings, an act perceived by the Albanian community as deliberate humiliation and denial of ethnic dignity, sparking widespread outrage and protests among immigrants in Boston and surrounding areas.[1] This event exposed the Greek Orthodox Church's alignment with anti-Albanian policies, including bans on vernacular services, which Albanian nationalists like Noli argued stifled national awakening.[17] Noli seized upon the incident as a catalyst for separatism, mobilizing emigrants to form independent Albanian Orthodox structures independent of Greek oversight. In response, community leaders established the Albanian Orthodox Society in Boston, selecting Noli—then untrained in priesthood but committed to the cause—as its spiritual guide, prompting him to seek ordination in New York under sympathetic Russian Orthodox auspices to lead vernacular services.[1] By 1908, this momentum led to the founding of the first Albanian parish in Boston, with Noli officiating in Albanian, a direct challenge to ecclesiastical authorities and a foundational step in institutionalizing Albanian religious nationalism abroad.[17] The incident not only accelerated Noli's rise as a community leader but also intertwined religious reform with political activism, as the push for autocephaly reinforced demands for Albanian sovereignty against imperial powers.[18]Religious Career

Ordination and Ministry in America

Fan Noli was ordained as a deacon on February 9, 1908, by Archbishop Platon Rozhdestvensky at St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York City.[9] Four days after his priestly ordination on March 18, 1908, at the same cathedral, Noli celebrated the first Divine Liturgy in the Albanian language on March 22, 1908, at Knights of Honor Hall in Boston, utilizing his own preliminary translations of liturgical texts.[9][2] As the inaugural priest of the Albanian Orthodox parish established amid immigrant communities, Noli's ministry emphasized vernacular worship to counter linguistic barriers in existing Orthodox congregations, which often prioritized Greek or Slavic rites.[9] He systematically translated key Orthodox service books into Albanian, publishing the Book of Holy Services in 1909 and the Book of Great Ceremonies in 1911, thereby standardizing Albanian ecclesiastical usage and enabling independent communal practices.[9] Noli's pastoral work in the United States centered on Albanian enclaves in Boston and New York, where he conducted services, preached, and organized religious education to sustain ethnic Orthodox identity amid assimilation pressures.[20] In August 1911, he extended his ministry abroad, touring Albanian communities in Europe—including Kishinev, Odessa, Bucharest, and Sofia—to perform liturgies in Albanian and advocate for cultural preservation.[9] These efforts laid the groundwork for structured Albanian Orthodoxy, blending spiritual leadership with communal cohesion until his elevation to the episcopate in 1923.[9]Founding the Albanian Orthodox Archdiocese

The need for Albanian-language Orthodox services among immigrants in the United States arose in the early 20th century, as most Albanian Orthodox were served by Greek or Slavic clergy who prioritized their own languages and customs, often marginalizing Albanian cultural identity. A pivotal catalyst was the "Hudson Incident" of late 1907 in Hudson, Massachusetts, where Albanian textile workers clashed with the local Greek priest over refusal to accommodate Albanian rites and alleged mistreatment, prompting demands for native clergy. Fan Noli, a 25-year-old Albanian student at Harvard University studying philosophy and pursuing a doctorate, stepped forward; having already translated key liturgical texts into Albanian, he sought ordination from Archbishop Platon Rozhdestvensky, head of the Russian Orthodox Mission in North America, which held jurisdiction over Orthodox in the U.S. at the time.[21][22] On February 9, 1908, Archbishop Platon ordained Noli as a deacon in New York City, followed by his priestly ordination on March 2, 1908, marking the first Albanian Orthodox priest in America. Noli celebrated the inaugural Divine Liturgy in Albanian on March 22, 1908, at the Knights of Honor Hall in Boston, drawing over 200 attendees and elevating the Albanian language to liturgical use for the first time outside Albania. This service laid the groundwork for organized Albanian Orthodoxy, leading directly to the establishment of the first Albanian parish, St. George Albanian Orthodox Church, in Boston later in 1908, initially meeting in rented spaces before acquiring a permanent site.[23][24] Noli's subsequent missionary efforts expanded the nascent structure, founding parishes in New England (e.g., Worcester and South Boston by 1910) and beyond, with communities in New York and Pennsylvania forming by the early 1910s, totaling around a dozen by the 1920s under his pastoral oversight. These efforts created a de facto Albanian diocese within the Russian jurisdiction, emphasizing ethnic autonomy while adhering to Orthodox canons, though formal independence came later. Noli's role as itinerant priest and organizer, often without fixed salary and supported by community donations, solidified the archdiocese's foundations amid challenges like jurisdictional rivalries and limited resources. By 1919, his leadership gained recognition as head of an independent Albanian diocese in America, predating broader autocephaly pushes.[21][17]Push for Autocephaly and Ecumenism

Fan S. Noli initiated efforts to establish an independent Albanian Orthodox presence in the United States amid resistance from Greek-dominated Orthodox structures, ordaining as a priest on March 18, 1908, and conducting the first Divine Liturgy in Albanian on March 22, 1908, in Boston.[9] He translated key Orthodox liturgies into Albanian, publishing editions in 1909 and 1911 to foster national linguistic identity in worship, which he employed during a 1911 tour of major European cities.[25] These actions laid the groundwork for detaching Albanian Orthodoxy from Hellenocentric administration under the Ecumenical Patriarchate, prioritizing vernacular services over Greek-language impositions that marginalized Albanian faithful.[9] Following Albanian independence in 1912, Noli returned to Albania, where he was ordained a bishop and assumed leadership of the nascent national church.[25] At the 1922 Congress of Berat, the Albanian Orthodox Church formally declared autocephaly, electing Noli as its first primate to assert ecclesiastical sovereignty from Constantinople's oversight.[25] [21] On November 21, 1923, he was consecrated as Bishop of Korçë and Metropolitan of Durrës, solidifying his hierarchical authority.[9] Full recognition of this autocephaly by the Ecumenical Patriarchate was granted only on April 12, 1937, after prolonged diplomatic negotiations amid regional Orthodox tensions.[9] Noli's ecumenical orientation predated widespread Orthodox engagement in inter-church dialogue, as he extended support to Albanian Muslim and Roman Catholic communities in America to preserve shared national heritage across denominations.[26] He provided fraternal assistance to figures like Imam Vehbi Ismail and Albanian Catholic prelates, advocating cooperation beyond confessional lines for ethnic unity.[26] This approach reflected his vision of religion as a vehicle for Albanian consolidation rather than division, influencing the Albanian Orthodox Church's early role as a pioneer in national-ecumenical initiatives, including invitations to observe events like the Lambeth Conference.[26]

Role in Albanian Independence

Exile Activism and Nationalist Writings

In the United States, where Fan Noli resided from 1906 onward as part of the Albanian diaspora, he emerged as a leading voice for Albanian nationalism amid the push for independence from Ottoman rule. He contributed to early émigré publications, including articles in Albanian-language periodicals that emphasized cultural preservation and political autonomy, drawing on his multilingual proficiency to bridge Albanian communities abroad.[2][12] Noli played a pivotal role in establishing the Pan-Albanian Federation of America (Vatra) in April 1912, co-founding the organization with other diaspora figures to coordinate advocacy for Albanian self-determination; he composed its anthem, "Vëllezërit, errësira" ("Brothers, Darkness"), which rallied support for national unity.[27] As editor of Dielli (The Sun), Vatra's official newspaper, from February 1909 to July 1911, Noli published editorials and essays promoting Albanian linguistic standardization, historical awareness, and resistance to Ottoman and neighboring powers' encroachments, instrumental in fostering diaspora cohesion.[28][22] His activism extended to international lobbying; between 1909 and 1919, Noli traveled to European capitals to petition governments and conferences on behalf of Albanian independence, leveraging Vatra's network to secure recognition amid World War I fragmentation.[12] In 1918, as Vatra president, he co-led the formation of a provisional Albanian government-in-exile in the U.S., comprising diaspora representatives to safeguard Albania's sovereignty against partition proposals at the Paris Peace Conference; this body issued memoranda asserting Albania's territorial integrity based on ethnic demographics and prior declarations of independence.[29][30] Noli also launched the English-language Adriatic Review in September 1918 to disseminate Albanian perspectives to Western audiences, highlighting Ottoman atrocities and the need for Allied intervention.[11] Noli's nationalist writings during this period focused on reviving Albanian identity through literature and history, including poetic calls for unity and translations of key texts to promote literacy in the vernacular. While his later works like the Scanderbeg biography expanded these themes, pre-1920 efforts centered on journalistic polemics in Dielli and Vatra organs, critiquing assimilationist pressures from Greece and Serbia and advocating democratic governance as essential to Albanian survival.[26][2] These publications, circulated among thousands of émigrés, amplified Vatra's fundraising and recruitment, directly aiding Albania's 1912 independence declaration by sustaining external pressure on imperial powers.[12]Participation in Congresses and Diplomacy

Fan Noli engaged in early diplomatic advocacy for Albanian independence from his base in the United States, where he served as secretary of the Pan-Albanian Federation of America (Vatra), established on April 28, 1912, to mobilize émigré support for national unification and autonomy.[27] In March 1913, he attended the Albanian Congress of Trieste, convened by Faik Konitza to coordinate strategies amid the Balkan Wars and Ottoman collapse.[31] That July, Noli made his first visit to Albania, conducting the inaugural Orthodox liturgy in Albanian on March 10, 1914, in Durrës to foster cultural and national cohesion.[32] Post-World War I, amid threats of partition under the 1919–1920 peace settlements, Noli spearheaded diplomatic campaigns for Albania's territorial integrity and reunification, leveraging his U.S. networks to secure endorsement from President Woodrow Wilson, who affirmed Albanian self-determination in correspondence and policy statements.[33][1] In 1918, he co-authored a memorandum submitted to Allied powers, urging recognition of Albania as a sovereign entity independent of neighboring states' claims.[30] These efforts extended to Geneva, where Noli represented Albanian interests at League of Nations proceedings, culminating in Albania's admission on December 17, 1920, after his persuasive defenses against Yugoslav and Italian territorial demands.[34][35] Noli later described the League membership as his paramount diplomatic success, establishing Albania's multilateral engagement and shielding it from absorption by Balkan rivals.[2] His advocacy emphasized Albania's ethnographic boundaries and non-aggressive stance, drawing on empirical mappings and historical precedents to counter adversarial narratives at international forums.[3] By prioritizing U.S. and British sympathies over regional powers, Noli's strategy aligned with realist assessments of great-power incentives, prioritizing verifiable alliances over ideological appeals.[36]Political Rise and the 1924 Revolution

Entry into Albanian Politics Post-Independence

Following Albania's declaration of independence on November 28, 1912, Noli visited the country for the first time in July 1913, marking his initial direct engagement with the nascent state amid ongoing territorial disputes and instability.[2] During this period, he conducted Albania's first Orthodox church service in the Albanian language on March 10, 1914, in Durrës, blending his religious advocacy with nationalist efforts to foster cultural autonomy.[13] These activities positioned him as a proponent of Albanian self-determination, though his stay was brief due to the outbreak of World War I, prompting his return to the United States for further diplomatic lobbying.[37] Noli's formal entry into domestic Albanian politics occurred in 1921, when he was elected to the Albanian parliament as a representative of the pro-British liberal People's Party, affiliated with the Vatra organization of Albanian émigrés.[8] This role allowed him to advocate for democratic reforms and resistance against territorial encroachments, particularly from Yugoslav forces, as evidenced by his address to the League of Nations in 1921 warning of Serbian ambitions toward Albanian regions like Mount Lurë.[38] In December 1921, under the government formed by Xhafer Ypi of the Popular Party, Noli was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, serving briefly alongside Ahmet Zogu as Minister of Internal Affairs.[37] In this capacity, he pursued policies emphasizing Albanian sovereignty and Western alignment, including appeals for international recognition and aid to stabilize the fragmented post-war state, though internal factionalism and Zogu's rising influence limited his tenure's effectiveness.[39] His resignation in early 1922 reflected growing tensions within the coalition, foreshadowing his opposition to authoritarian tendencies in Albanian governance.[2]The June Revolution Against Zogu

The assassination of Avni Rustemi, a prominent nationalist and leader of the democratic opposition, on April 20, 1924, in Tirana served as the immediate catalyst for the uprising against Ahmet Zogu's regime.[40] Rustemi, who had previously attempted to assassinate Zogu in 1923, was shot by agents widely believed to be acting on Zogu's orders, amid accusations of electoral fraud in the 1923 parliamentary elections and broader corruption within Zogu's government, which had consolidated power through tribal loyalties and suppression of rivals.[41] [4] Fan Noli, a vocal critic of Zogu's authoritarian tendencies and advocate for democratic reforms, emerged as the figurehead of the opposition despite his clerical background and limited military experience.[41] From his position within Albania's political circles, Noli coordinated with democratic factions, including remnants of the National Revolutionary Committee formed after Rustemi's death, mobilizing support from intellectuals, urban youth, and dissident military units disillusioned with Zogu's favoritism toward northern clans.[4] By late May 1924, rebel forces numbering over 12,000, drawn from diverse regions including Kosovo and southern Albania, began converging on the capital, reflecting widespread resentment against Zogu's perceived feudal alliances and failure to address economic stagnation.[4] [42] The revolutionary offensive intensified in early June, with insurgents launching attacks on government garrisons starting around June 7, exploiting Zogu's overstretched defenses and eroding loyalty among his troops.[42] On June 10, armed democratic forces entered Tirana with minimal resistance, as Zogu's appeals for defense failed to rally local support, leading to the rapid collapse of his administration.[4] Zogu fled to Yugoslavia on June 11, accompanied by loyalists, abandoning the capital amid reports of defections and public indifference to his regime's survival.[41] The revolution's success paved the way for Noli's assumption of leadership, as opposition leaders formally proclaimed a new government on June 16, 1924, with Noli appointed prime minister and foreign minister, marking the temporary ousting of Zogu and the establishment of a provisional democratic authority committed to anti-corruption measures and national unification.[43] This outcome, however, rested on fragile alliances, as the insurgents' momentum derived more from anti-Zogu sentiment than unified ideological commitment, setting the stage for subsequent instability.[4]Premiership: Policies, Reforms, and Instability

Fan S. Noli assumed the premiership on July 17, 1924, following the ouster of Ahmet Zogu's regime in the June Revolution, forming a cabinet that proclaimed democratic ideals and vowed to combat entrenched corruption and feudal influences.[44] The government prioritized liberal reforms to modernize Albania, including tentative steps toward agrarian redistribution to alleviate peasant burdens and undermine large landholders' power, though Noli's reluctance to fully enact these measures alienated potential rural supporters and conservative elites who resisted such changes.[4][7] In foreign policy, Noli sought to bolster legitimacy through diplomatic overtures, reopening talks with Soviet Russia for recognition as early as July 4, 1924, while appealing to Britain and the United States for financial aid and protection against regional threats, viewing them as guarantors of his reformist agenda amid Albania's precarious independence.[7][36] Domestically, the administration pursued anti-corruption drives and institutional modernization, such as facilitating foreign investment to address fiscal deficits, but these efforts were hampered by the absence of a stable parliament and reliance on revolutionary decrees rather than broad electoral mandates.[6] Instability plagued the regime from inception, stemming from Noli's idealistic focus on ethical governance over pragmatic power consolidation, which left the government vulnerable to military disloyalty and economic strain without secured loans or revenues.[7] Traditional landowners and Zogu loyalists mounted opposition, exacerbating divisions between urban intellectuals and rural conservatives, while the regime's inability to control northern tribal militias or counter external Yugoslav backing for Zogu eroded territorial authority.[4] By late December 1924, these fractures culminated in Zogu's forces, aided by Yugoslav troops, capturing Tirana on December 24, toppling Noli's government after approximately five months in power.[41]Downfall, Exile, and Later Years

Zogu's Coup and Immediate Aftermath

Ahmet Zogu, having fled to Yugoslavia following the June Revolution, launched a counter-coup on December 13, 1924, leading an invasion force into northern Albania supported by Yugoslav financing and including White Russian émigré troops alongside local tribal militias from the Dibra and Mati regions.[41] [43] The incursion faced minimal organized resistance, as Noli's government, plagued by internal divisions, economic instability, and failure to secure broad international backing, collapsed rapidly amid defections and disarray in Tirana.[41] By late December, Zogu's forces had advanced to the capital, prompting Noli to resign and flee into exile, initially seeking refuge in Italy before continuing opposition activities abroad.[43] [45] In the immediate aftermath, Zogu consolidated power by reconvening a compliant parliament in January 1925, which drafted a new constitution granting him executive authority as president of the newly proclaimed Albanian Republic on January 31, 1925.[41] Loyalist forces under Zogu suppressed remaining Noli supporters, executing or imprisoning key opposition figures and disbanding revolutionary committees, while Zogu pursued alliances with Yugoslavia to stabilize his rule despite underlying tensions over border claims.[43] Noli, from exile, denounced the coup as a foreign-backed restoration of autocracy, but his appeals for intervention from Western powers, including Britain and the United States, yielded no substantive support, isolating him further as Zogu's regime prioritized internal security and diplomatic realignments.[36] This swift reversal ended Noli's brief democratic experiment, shifting Albania toward centralized governance under Zogu, who balanced tribal loyalties with nascent state-building efforts amid persistent factionalism.[41]Exile in Europe and the United States

Following the collapse of his government on December 24, 1924, Noli fled Albania amid Zogu's counter-coup and entered exile, initially drifting across Europe without a fixed base.[9] He resided primarily in Austria and Germany during the late 1920s, including extended stays in Vienna, from where he issued public condemnations of Zogu's consolidation of power, such as denouncing the latter's self-proclaimed kingship in September 1928 as a betrayal of Albanian democratic aspirations.[46] Albanian courts under Zogu sentenced Noli to death in absentia in 1927 for his role in the June Revolution, further solidifying his status as a political fugitive.[47] In 1930, Noli returned to the United States—where he had first arrived in 1906 and built ties within the Albanian diaspora—on a six-month visa, establishing a temporary base in Boston, Massachusetts, and launching the periodical Republika to advocate for Albanian republicanism.[1] Upon visa expiration, he was compelled to depart for Europe, but in 1932, aided by supporters in the Albanian-American community, he re-entered the U.S. and secured permanent resident status.[2] By the mid-1930s, Noli had obtained U.S. citizenship, reportedly on the condition of refraining from direct anti-Zogu agitation, though he briefly organized Republican opposition circles upon his 1932 arrival.[8] Settling permanently in Boston, Noli resumed leadership of the Albanian Orthodox Archdiocese in America, which he had helped establish decades earlier, conducting services in Albanian and fostering cultural preservation among immigrants.[33] His exile years in the U.S. shifted emphasis from overt politics to ecclesiastical administration, linguistic scholarship, and translations, while maintaining informal influence within émigré networks opposed to Zogu's monarchy until the latter's 1939 overthrow by Italian forces.[1] This period marked Noli's transition from revolutionary statesman to diaspora intellectual, insulated from Albanian domestic affairs by geographic distance and U.S. authorities' stipulations.[8]Final Years and Death

In 1953, Noli relocated to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, purchasing a home with funds from a $20,000 grant provided by the Vatra Federation, an Albanian-American organization.[9] This move marked his retirement from more active leadership roles within the Albanian Orthodox Archdiocese of America, where he had served as Metropolitan Theophan Noli since the 1920s, overseeing liturgical translations and ecclesiastical affairs for Albanian immigrants.[1] Despite his advanced age, he maintained involvement in cultural and religious preservation efforts among the diaspora until health declined. Noli died on March 13, 1965, in Fort Lauderdale at the age of 83.[17] The immediate cause was a cerebral hemorrhage following surgery, from which he did not recover due to his age.[1] His passing concluded a life of exile that began after the 1924 political upheaval in Albania, during which he had evaded execution under Zog's regime while continuing advocacy from abroad.[17]Literary and Intellectual Contributions

Original Poetry and Theological Works

Fan S. Noli composed original poetry in Albanian, often infused with patriotic lament, historical reflection, and exile motifs, reflecting his experiences after the 1924 political upheaval. His poem Anës Lumenjve ("By the Rivers"), published in 1928, evokes the Babylonian captivity to parallel Albanian dispersion and suffering, portraying rivers like the Elbe and Spree as sites of unending sorrow and lost homeland.[48] Similarly, Merr e Zgjidh ("Choose and Take"), written in 1924 amid revolutionary fervor, rallies for resolute fighters against retreating foes, emphasizing unyielding commitment to national struggle.[49] Another early work, Hymni i Flamurit ("Hymn to the Flag"), exalts Albania's blood-red banner as a symbol of endurance, maternal sacrifice, and ancestral legacy.[50] Noli's poetic corpus, compiled in collections like Albumi by 1948, totals dozens of verses produced sporadically until his final originals in the early 1960s, blending rhythmic innovation—drawn from his musical background—with concise, evocative language to stir Albanian identity.[51] These works prioritize moral exhortation over ornate style, often employing direct address and repetition for emphatic impact. Theologically, Noli's original contributions manifest primarily through poetry laden with biblical symbolism, serving as vehicles for religious and ethical instruction rather than systematic treatises. Poems draw on scriptural motifs—such as exile paralleling Psalmic laments—to impart lessons of divine justice, human frailty, and redemptive hope, positioning literature as a didactic tool aligned with Orthodox moralism.[52] His verse thus bridges personal piety and national revival, though distinct prose theological texts remain undocumented in accessible records, with emphasis instead on his ecclesiastical leadership and scriptural adaptations.[53]Translations and Linguistic Innovations

Fan S. Noli produced numerous translations of Western literary masterpieces into Albanian, significantly enriching the language's expressive capacity during a period of national linguistic consolidation. His renditions of William Shakespeare's plays, including Othello (translated in 1916 as the first Shakespearean work into Albanian), Macbeth, and others, employed a refined Tosk dialect to convey dramatic intensity and poetic nuance, introducing sophisticated vocabulary and idiomatic structures absent in prior Albanian prose.[54][55] These efforts not only popularized Shakespeare in Albania but also elevated Albanian literary standards by adapting Elizabethan rhetoric to native phonetic and syntactic patterns.[56] Noli's translation of Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote (published in two volumes as Sojliu mendje-mprehtë Don Kishoti i Mançës in 1932–1933) marked the inaugural full Albanian version of the novel, spanning over 1,000 pages and faithfully reproducing the original's satirical tone while coining terms for abstract concepts like chivalric idealism.[57] He also rendered works by Edgar Allan Poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Omar Khayyam into Albanian, prioritizing fidelity to source rhythms and metaphors to foster a modern literary idiom.[53] In religious domains, Noli translated Byzantine liturgical texts from Greek into Albanian, comprising roughly half of his published output, often with parallel English versions and musical notations adapted for Orthodox chant.[53] Notable among these is his 1908 rendition of the Divine Liturgy, which enabled the first Albanian-language Orthodox service on March 22, 1910, in Boston, and later works like the 1956 Gospel Lectionary.[24][58] These translations standardized ecclesiastical Albanian terminology, drawing on archaic and dialectal forms to preserve theological precision while making rituals accessible to laity.[59] Linguistically, Noli innovated by advocating the Latin alphabet's exclusive use for Albanian, aiding its shift from Ottoman-era scripts and promoting phonetic orthography to reflect spoken Tosk variants.[57] His selective revival of Old Albanian lexicon—evident in Shakespearean translations where archaic words evoked stylistic depth—expanded vocabulary for emotion, philosophy, and satire, countering lexical gaps in emerging standard Albanian.[60] Through contextual adaptation rather than literalism, Noli's works fostered causal links between source intent and target idiom, enhancing Albanian's suitability for complex narrative and rhetoric without diluting indigenous flavor.[61][59]Legacy and Historiographical Debates

Contributions to Albanian Nationalism and Orthodoxy

Fan Noli played a pivotal role in advancing Albanian nationalism by integrating Orthodox religious practice with cultural and linguistic independence, countering Greek ecclesiastical dominance that had historically suppressed Albanian identity. In the United States, where he emigrated in 1906, Noli founded the first Albanian Orthodox parish in Boston in 1908, emphasizing services in the Albanian language to foster ethnic cohesion among diaspora communities facing discrimination from Greek-controlled Orthodox structures.[62][63] On February 9, 1908, he was ordained as a deacon and subsequently as a priest by Archbishop Platon of the Russian Orthodox Church in America, enabling him to lead Albanian-language worship that reinforced national consciousness.[63] Returning to Albania, Noli's ecclesiastical leadership culminated in the autocephaly of the Orthodox Church of Albania. Consecrated as Bishop of Korçë in 1922, he advocated for an independent Albanian Orthodox hierarchy, free from the Ecumenical Patriarchate's oversight, which had prioritized Greek interests.[9] In 1923, under his primacy as Metropolitan Theophan of Durrës, the church formally declared itself autocephalous, a move that symbolized religious sovereignty and bolstered Albanian nationalism by aligning faith with national self-determination.[9] This independence addressed long-standing grievances over Hellenization policies, allowing Albanians to practice Orthodoxy in their vernacular and reducing foreign cultural influence.[62] Noli's translations of sacred texts further intertwined Orthodoxy with nationalism, enriching the Albanian language and promoting literacy as tools of cultural revival. He rendered the Bible, liturgy, and theological works into Albanian, making religious doctrine accessible and embedding national identity within spiritual life.[8] These efforts, alongside his journalism and writings for the nationalist cause, positioned him as a recognized leader in the Albanian Orthodox community and the broader independence movement, where he emphasized democratic ideals and anti-imperialist resistance.[2] By 1923, his initiatives had established Albanian-speaking Orthodoxy not only in Albania but also enduringly in the United States, sustaining diaspora ties to the homeland.[9]