Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

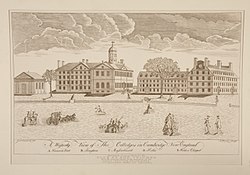

Harvard University

View on Wikipedia

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 as New College, and later named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States. Its influence, wealth, and rankings have made it one of the most prestigious universities in the world.[10]

Key Information

Harvard was founded and authorized by the Massachusetts General Court, the governing legislature of colonial-era Massachusetts Bay Colony.[11] While never formally affiliated with any Protestant denomination, Harvard trained Congregational clergy until its curriculum and student body were gradually secularized in the 18th century. By the 19th century, Harvard had emerged as the most prominent academic and cultural institution among the Boston elite.[12][13] Following the American Civil War, under Harvard president Charles William Eliot's long tenure from 1869 to 1909, Harvard developed multiple professional schools, which transformed it into a modern research university. In 1900, Harvard co-founded the Association of American Universities.[14] James B. Conant led the university through the Great Depression and World War II, and liberalized admissions after the war.

The university has ten academic faculties and a faculty attached to Harvard Radcliffe Institute. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences offers study in a wide range of undergraduate and graduate academic disciplines, and other faculties offer graduate degrees, including professional degrees. Harvard has three campuses:[15] the main campus, a 209-acre (85 ha) in Cambridge centered on Harvard Yard; an adjoining campus immediately across Charles River in the Allston neighborhood of Boston; and the medical campus in Boston's Longwood Medical Area.[16] Harvard's endowment, valued at $53.2 billion, makes it the wealthiest academic institution in the world.[17][18] Harvard Library, with more than 20 million volumes, is the world's largest academic library.

Harvard alumni, faculty, and researchers include 188 living billionaires, 8 U.S. presidents, 24 heads of state and 31 heads of government, founders of notable companies, Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, members of Congress, MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, Turing Award Recipients, Pulitzer Prize recipients, and Fulbright Scholars; by most metrics, Harvard University ranks among the top universities in the world in each of these categories.[Notes 1] Harvard students and alumni have also collectively won 10 Academy Awards and 110 Olympic medals, including 46 gold medals.

History

[edit]Colonial era

[edit]

Harvard was founded in 1636 by a vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Its first headmaster, Nathaniel Eaton, took office the following year. In 1638, the university acquired English North America's first known printing press.[19][20] The same year, on his deathbed, John Harvard, a Puritan clergyman who had emigrated to the colony from England, bequeathed the emerging college £780 and his library of some 320 volumes;[21] the following year, it was named Harvard College.

In 1643, a Harvard publication defined the college's purpose: "[to] advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust."[22]

In its early years, the college trained many Puritan Congregational ministers[23] and offered a classical curriculum based on the English university model exemplified by the University of Cambridge, where many colonial Massachusetts leaders had studied prior to emigrating to the colony. Harvard College never formally affiliated with any particular Protestant denomination, but its curriculum conformed to the tenets of Puritanism.[24] In 1650, the charter for Harvard Corporation, the college's governing body, was granted.

From 1681 to 1701, Increase Mather, a Puritan clergyman, served as Harvard's sixth president. In 1708, John Leverett became Harvard's seventh president and the first president who was not also a clergyman.[25] Harvard faculty and students largely supported the Patriot cause during the American Revolution.[26][27]

The earliest known official seal of Harvard University, commonly referred to as the Seal of 1650 or the In Christi Gloriam seal, features a square shield bearing three open books arranged around a central chevron. This design symbolizes the pursuit of learning under divine guidance. The motto IN CHRISTI GLORIAM ("To the glory of Christ") appears prominently on the seal, which is encircled by the Latin inscription SIGILL COL HARVARD CANTAB NOV ANGL 1650, meaning "Seal of Harvard College, Cambridge, New England, 1650." This seal reflects the original religious mission of the institution.

In 1885, the Harvard Corporation adopted a revised design known as the Appleton Seal, based on an earlier version created by President Josiah Quincy in 1843. Designed by William Sumner Appleton (Harvard AB 1860), the seal features a triangular shield bearing three open books with the motto VERITAS ("Truth"). Surrounding the shield is the motto CHRISTO ET ECCLESIÆ ("For Christ and the Church"), and the outer border bears the inscription SIGILLVM ACADEMIÆ HARVARDINÆ IN NOV. ANG. ("Seal of Harvard College in New England"). This version of the seal sought to harmonize the university's intellectual pursuits with its ecclesiastical roots.[28]

19th century

[edit]

In the 19th century, Harvard was influenced by Enlightenment Age ideas, including reason and free will, which were widespread among Congregational ministers and which placed these ministers and their congregations at odds with more traditionalist, Calvinist pastors and clergies.[29]: 1–4 Following the death of Hollis Professor of Divinity David Tappan in 1803 and that of Joseph Willard, Harvard's eleventh president, the following year, a struggle broke out over their replacements. In 1805, Henry Ware was elected to replace Tappan as Hollis chair. Two years later, in 1807, liberal Samuel Webber was appointed as Harvard's 13th president, representing a shift from traditional ideas at Harvard to more liberal and Arminian ideas.[29]: 4–5 [30]: 24

In 1816, Harvard University launched new language programs in the study of French and Spanish, and appointed George Ticknor the university's first professor for these language programs.

From 1869 to 1909, Charles William Eliot, Harvard University's 21st president, decreased the historically favored position of Christianity in the curriculum, opening it to student self-direction. Though Eliot was an influential figure in the secularization of U.S. higher education, he was motivated primarily by Transcendentalist and Unitarian convictions influenced by William Ellery Channing, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and others, rather than secularism. In the late 19th century, Harvard University's graduate schools began admitting women in small numbers.[31]

20th century

[edit]

In 1900, Harvard became a founding member of the Association of American Universities.[14] For the first few decades of the 20th century, the Harvard student body was predominantly "old-stock, high-status Protestants, especially Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians," according to sociologist and author Jerome Karabel.[33]

Over the 20th century, as its endowment burgeoned and prominent intellectuals and professors affiliated with it, Harvard University's reputation as one of the world's most prestigious universities grew notably. The university's enrollment also underwent substantial growth, a product of both the founding of new graduate academic programs and an expansion of the undergraduate college. Radcliffe College emerged as the female counterpart of Harvard College, becoming one of the most prominent schools in the nation for women.

In 1923, a year after the proportion of Jewish students at Harvard reached 20%, A. Lawrence Lowell, the university's 22nd president, unsuccessfully proposed capping the admission of Jewish students to 15% of the undergraduate population. Lowell also refused to mandate forced desegregation in the university's freshman dormitories, writing that, "We owe to the colored man the same opportunities for education that we do to the white man, but we do not owe to him to force him and the white into social relations that are not, or may not be, mutually congenial."[34][35][36][37]

Between 1933 and 1953, Harvard University was led by James B. Conant, the university's 23rd president, who reinvigorated the university's creative scholarship in an effort to guarantee Harvard's preeminence among the nation and world's emerging research institutions. Conant viewed higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy, and devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. In 1945, under Conant's leadership, an influential 268-page report, General Education in a Free Society, was published by Harvard faculty, which remains one of the most important works in curriculum studies,[38] and women were first admitted to the medical school.[39]

Between 1945 and 1960, admissions were standardized to open the university to a more diverse group of students. Following the end of World War II, for example, special exams were developed so veterans could be considered for admission.[40] No longer drawing mostly from prestigious prep schools in New England, the undergraduate college became accessible to striving middle class students from public schools; many more Jews and Catholics were admitted, but Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians remained underrepresented.[41] Over the second half of the 20th century, however, the university became incrementally more diverse.[42]

Between 1971 and 1999, Harvard controlled undergraduate admission, instruction, and housing for Radcliffe's women; in 1999, Radcliffe was formally merged into Harvard University.[43]

21st century

[edit]

On July 1, 2007, Drew Gilpin Faust, dean of Harvard Radcliffe Institute, was appointed Harvard's 28th and the university's first female president.[44] On July 1, 2018, Faust retired and joined the board of Goldman Sachs, and Lawrence Bacow became Harvard's 29th president.[45]

In February 2023, approximately 6,000 Harvard workers attempted to organize a union.[46]

Bacow retired in June 2023, and on July 1 Claudine Gay, a Harvard professor in the Government and African American Studies departments and Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, became Harvard's 30th president. In January 2024, just six months into her presidency, Gay resigned following allegations of antisemitism and plagiarism.[47] Gay was succeeded by Alan Garber, the university's provost, who was appointed interim president. In August 2024, the university announced that Garber would be appointed Harvard's 31st president through the end of the 2026–27 academic year.

Second presidency of Donald Trump

[edit]In February 2025, Leo Terrell, the head of the Trump administration's Task Force to Combat Antisemitism, announced that he would investigate Harvard University as part of the Department of Justice's broader investigation into antisemitism on college campuses.[48]

In April 2025, the United States federal government under President Donald Trump threatened to withhold nearly $9 billion in government funds from the university unless the university complied with government demands to modify many of its policies. This threat was part of a broader battle over universities' autonomy following contentious student protests against the Gaza war, and followed similar demands made of Columbia University.[49] The university's leadership resisted the government's demands, claiming that they were an unlawful overreach of government authority.[50] In response, the US Department of Education announced they were freezing $2.3 billion in federal funds to Harvard.[51] The Department of Homeland Security subsequently threatened to revoke Harvard's eligibility to host international students.[49] Harvard responded by filing a lawsuit against the Trump administration in the District Court of Massachusetts, arguing that the freezing of funds was unconstitutional.[52][53][54]

In May 2025, education secretary Linda McMahon informed Harvard president Garber that the federal government would no longer provide grant funding until the university complied with the Trump administration's demands.[55] The following week, the Trump administration cut an additional $450 million in grants to the school.[56]

Later that same month, Department of Homeland Security secretary Kristi Noem announced that Harvard's Student and Exchange Visitor Program certification had been revoked, barring Harvard from hosting international students.[57][58] The following day, Harvard sued the Trump administration for banning them from enrolling international students and U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs granted a temporary restraining order stopping the ban.[59][60][61][62] On June 16, 2025, Burroughs postponed a ruling after hearing arguments from lawyers on both sides, leaving the temporary block in place for another week.[63]

On May 30, 2025, the State Department ordered all US embassies and consulates to conduct "comprehensive and thorough vetting" of the online presence of anyone seeking to visit Harvard from abroad.[64]

On June 4, 2025, Trump issued a proclamation restricting international students from studying at Harvard, and directing the State Department to consider revoking the visas of current international students studying at that university.[65][66] The following day, Harvard filed a legal challenge, amending their existing federal complaint against the administration.[67][68][69]

On June 20, Harvard was granted an injunction allowing it to continue hosting international students as litigation continues.[70] On June 30, a Trump administration investigation found Harvard violated federal civil rights law by failing to protect Jewish students, faculty, and staff.[71]

On September 3, 2025 US District Judge Allison Burroughs ruled the Trump administration illegally froze more than $2 billion in research funding stating the administration "...violated Harvard's free-speech rights as well as the US Civil Rights Act."[72]

Campuses

[edit]Cambridge

[edit]

The 209-acre (85 ha) main campus of Harvard University is centered on Harvard Yard, colloquially known as "the Yard", in Cambridge, Massachusetts, about three miles (five km) west-northwest of downtown Boston, and extending to the surrounding Harvard Square neighborhood. The Yard houses several Harvard buildings, including four of the university's libraries, Houghton, Lamont, Pusey, and Widener. Also on Harvard Yard are Massachusetts Hall, built between 1718 and 1720 and the university's oldest still standing building, Memorial Church, and University Hall.

Harvard Yard and adjacent areas include the main academic buildings of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, including Sever Hall, Harvard Hall, and freshman dormitories. Upperclassmen live in the twelve residential houses, located south of Harvard Yard near the Charles River and on Radcliffe Quadrangle, which formerly housed Radcliffe College students. Each house is a community of undergraduates, faculty deans, and resident tutors, with its own dining hall, library, and recreational facilities.[74]

Also on the main campus in Cambridge are the Law, Divinity (theology), Engineering and Applied Science, Design (architecture), Education, Kennedy (public policy), and Extension schools, and Harvard Radcliffe Institute in Radcliffe Yard.[75] Harvard also has commercial real estate holdings in Cambridge.[76][77]

Allston

[edit]Harvard Business School, Harvard Innovation Labs, and many athletics facilities, including Harvard Stadium, are located on a 358-acre (145 ha) campus in the Allston section of Boston across the John W. Weeks Bridge, which crosses the Charles River and connects the Allston and Cambridge campuses.[78]

The university is actively expanding into Allston, where it now owns more land than in Cambridge.[79] Plans include new construction and renovation for the Business School, a hotel and conference center, graduate student housing, Harvard Stadium, and other athletics facilities.[80]

In 2021, the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences expanded into the new Allston-based Science and Engineering Complex (SEC), which is more than 500,000 square feet in size.[81] SEC is adjacent to the Enterprise Research Campus, the Business School, and Harvard Innovation Labs, and designed to encourage technology- and life science-focused startups and collaborations with mature companies.[82]

Longwood

[edit]

The university's schools of Medicine, Dental Medicine, and Public Health are located on a 21-acre (8.5 ha) campus in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area in Boston, about 3.3 miles (5.3 km) south of the Cambridge campus.[16]

Several Harvard-affiliated hospitals and research institutes are also in Longwood, including Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Children's Hospital, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Joslin Diabetes Center, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. Additional affiliates, including Massachusetts General Hospital, are located throughout Greater Boston.

Other

[edit]Harvard owns Dumbarton Oaks, a research library in Washington, D.C., Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts, Concord Field Station in Estabrook Woods in Concord, Massachusetts,[83] the Villa I Tatti research center in Florence, Italy,[84] and the Center for Hellenic Studies in Greece. The Harvard Shanghai Center in Shanghai, China,[85] and Arnold Arboretum in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston.

Organization and administration

[edit]Governance

[edit]Harvard is governed by a combination of its Board of Overseers and the President and Fellows of Harvard College, which is also known as the Harvard Corporation. These two bodies, in turn, appoint the President of Harvard University.[86]

There are 16,000 staff and faculty,[87] including 2,400 professors, lecturers, and instructors.[88]

As of 2025, Harvard differs radically from its peer universities in two important ways. First, Harvard does not make its governing statutes publicly available, meaning that members of the Harvard community interested in reform must first persuade the university to give them a copy of those documents. Second, Harvard does not have an academic senate like most of its peers, although it is currently attempting to create one.[89]

Endowment

[edit]Harvard has the largest university endowment in the world, valued at about $50.7 billion as of 2023.[17][18]

During the recession of 2007–2009, it suffered significant losses that forced large budget cuts, in particular temporarily halting construction on the Allston Science Complex.[90] The endowment has since recovered.[91][92][93][94]

About $2 billion of investment income is annually distributed to fund operations.[95] Harvard's ability to fund its degree and financial aid programs depends on the performance of its endowment; a poor performance in fiscal year 2016 forced a 4.4% cut in the number of graduate students funded by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.[96] Endowment income is critical, as only 22% of revenue is from students' tuition, fees, room, and board.[97]

Divestment

[edit]Since the 1970s, several student-led campaigns have advocated divesting Harvard's endowment from controversial holdings, including investments in South Africa during apartheid, Sudan during the Darfur genocide, and tobacco, fossil fuel, and private prison industries.[98][99]

In the late 1980s, during the disinvestment from South Africa movement, student activists erected a symbolic shanty town on Harvard Yard and blockaded a speech by South African Vice Consul Duke Kent-Brown.[100][101]

In response to pressure, the university eventually reduced its South African holdings by $230 million out of a total of $400 million between 1986 and 1987.[100][102]

Academics

[edit]Teaching and learning

[edit]| School | Founded |

| Harvard College | 1636 |

| Medicine | 1782 |

| Divinity | 1816 |

| Law | 1817 |

| Engineering | 1847 |

| Dental Medicine | 1867 |

| Graduate Arts and Sciences | 1872 |

| Business | 1908 |

| Extension | 1910 |

| Design | 1936 |

| Education | 1920 |

| Public Health | 1913 |

| Government | 1936 |

Harvard is a large, highly residential research university[103] offering 50 undergraduate majors,[104] 134 graduate degrees,[105] and 32 professional degrees.[106] During the 2018–2019 academic year, Harvard granted 1,665 baccalaureate degrees, 1,013 graduate degrees, and 5,695 professional degrees.[106]

Harvard College, the four-year, full-time undergraduate program, has a liberal arts and sciences focus.[103][104] To graduate in the usual four years, undergraduates normally take four courses per semester.[107] In most majors, an honors degree requires advanced coursework and a senior thesis.[108]

Though some introductory courses have large enrollments, the median class size is 12 students.[109]

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences, with an academic staff of 1,211 as of 2019, is the largest Harvard faculty, and has primary responsibility for instruction in Harvard College, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and the Division of Continuing Education, which includes Harvard Summer School and Harvard Extension School. There are nine other graduate and professional faculties and a faculty attached to the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

There are four Harvard joint programs with MIT, which include the Harvard–MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology, the Broad Institute, The Observatory of Economic Complexity, and edX.

Professional schools

[edit]The university maintains 12 schools, which include:

| School | Founded | Enrollment[110][failed verification] |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine | 1782 | 660 |

| Divinity | 1816 | 377 |

| Law | 1817 | 1,990 |

| Dental Medicine | 1867 | 280 |

| Graduate Arts and Sciences | 1872 | 4,824 |

| Business | 1908 | 2,011 |

| Extension | 1910 | 3,428 |

| Design | 1914 | 878 |

| Education | 1920 | 876 |

| Public Health | 1922 | 1,412 |

| Government | 1936 | 1,100 |

| Engineering | 2007 | 1,750 (including undergraduates) |

Research

[edit]Harvard is a founding member of the Association of American Universities[111] and a preeminent research university with "very high" research activity (R1) and comprehensive doctoral programs across the arts, sciences, engineering, and medicine, according to the Carnegie Classification.[103]

The medical school consistently ranks first among medical schools for research,[112] and biomedical research is an area of particular strength for the university. More than 11,000 faculty and 1,600 graduate students conduct research at the medical school and its 15 affiliated hospitals and research institutes.[113] In 2019, the medical school and its affiliates attracted $1.65 billion in competitive research grants from the National Institutes of Health, more than twice that of any other university.[114]

Libraries

[edit]

Harvard Library, the largest academic library in the world with 20.4 million holdings, is centered in Widener Library in Harvard Yard. It includes 25 individual Harvard libraries around the world with a combined staff of more than 800 librarians and personnel.[115]

Houghton Library, the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, and the Harvard University Archives consist principally of rare and unique materials. The nation's oldest collection of maps, gazetteers, and atlases is stored in Pusey Library on Harvard Yard, which is open to the public. The largest collection of East-Asian language material outside of East Asia is held in Harvard-Yenching Library.

Other major libraries in the Harvard Library system include Baker Library/Bloomberg Center at Harvard Business School, Cabot Science Library at Harvard Science Center, Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., Gutman Library at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Harvard Film Archive at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Houghton Library, and Lamont Library.

Museums

[edit]Harvard Art Museums includes three museums, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum covers Asian, Mediterranean, and Islamic art; the Busch–Reisinger Museum (formerly the Germanic Museum) covers central and northern European art; and the Fogg Museum covers Western art from the Middle Ages to the present emphasizing Italian early Renaissance, British pre-Raphaelite, and 19th-century French art.

Harvard Museums of Science and Culture include the Harvard Museum of Natural History, which itself includes the Harvard Mineralogical and Geological Museum, the Harvard University Herbaria featuring the Blaschka Glass Flowers exhibit, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Others include the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments at Harvard Science Center, the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East featuring artifacts from excavations in the Middle East, and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, specializing in the cultural history and civilizations of the Western Hemisphere, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, designed by Le Corbusier and housing the Harvard Film Archive, the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard Medical School's Center for the History of Medicine, and the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Reputation and rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[116] | 8 |

| U.S. News & World Report[117] | 3 |

| Washington Monthly[118] | 1 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[119] | 6 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[120] | 1 |

| QS[121] | 5 |

| THE[122] | 3 |

| U.S. News & World Report[123] | 1 |

Harvard University is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[124] Since its founding in 2003, the Academic Ranking of World Universities has ranked Harvard first in each of its annual rankings of the world's colleges and universities. Similarly, the Times Higher Education–QS World University Rankings, which was published from 2004 to 2009, ranked Harvard first in the world in each of its annual rankings. Since then, Harvard has been ranked first in the world each year since 2011 by its successor, the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[125]

Harvard was also ranked in the first tier of American research universities, along with Columbia, MIT, and Stanford, in the 2023 report from the Center for Measuring University Performance.[126]

Among rankings of specific indicators, Harvard topped both the University Ranking by Academic Performance in 2019–20 and Mines ParisTech: Professional Ranking of World Universities in 2011, which measured universities' numbers of alumni holding CEO positions in Fortune Global 500 companies.[127] According to annual polls done by The Princeton Review, Harvard is consistently among the top two most commonly named dream colleges in the United States for both students and their parents.[128][129][130][131]

In 2019, Harvard's engineering school was ranked the third-best school in the world for engineering and technology by Times Higher Education.[132]

In international relations, Foreign Policy magazine ranks Harvard best in the world at the undergraduate level and second in the world at the graduate level, behind the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.[133]

| Race and ethnicity | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 33% | ||

| Asian | 22% | ||

| International student | 14% | ||

| Hispanic | 12% | ||

| Black | 9% | ||

| Two or more races | 7% | ||

| Unknown | 2% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[a] | 17% | ||

| Affluent[b] | 83% | ||

Student activities

[edit]Student government

[edit]The Undergraduate Council represented Harvard College undergraduate students until it was dissolved in 2022,[135] and replaced by the Undergraduate Association. The Graduate Council represents students at all twelve graduate and professional schools, most of which also have their own student government.[136]

Student media

[edit]The Harvard Crimson, founded in 1873 and run entirely by Harvard undergraduate students, is the university's primary student newspaper. Many notable alumni have worked at the Crimson, including two U.S. presidents, Franklin D. Roosevelt (AB, 1903) and John F. Kennedy (AB 1940).

Athletics

[edit]

Harvard College competes in the NCAA Division I Ivy League conference. The school fields 42 intercollegiate sports teams, more than any other college in the country.[137]

Harvard and the other seven Ivy League universities are prohibited from offering athletic scholarships.[138] The school color is crimson.[139]

National championships

[edit]In the NCAA Division I era, which began in 1973, Harvard Crimson teams have won five NCAA Division I championships as of 2024: men's ice hockey in 1989, women's lacrosse in 1990, women's rowing in 2003, and men's fencing in 2006 and 2024. Including the pre-NCAA era, Harvard has won 159 national championships across all sports. Its men's squash team holds the record for the most national collegiate championships in the sport. Harvard's first national championship came in 1880, when its track and field team won the national championship.[140]

Rivalries

[edit]Harvard's athletic programs maintain a long-standing rivalry with Yale in all sports, especially in college football, where Harvard and Yale compete in an annual football rivalry, which has played 139 times as of 2024, dating back to its first meeting in 1875.[141]

Every two years, Harvard and Yale track and field teams come together to compete against a combined Oxford and Cambridge team in the oldest continuous international amateur competition in the world.[142]

In men's ice hockey, Harvard maintains a historic rivalry with Cornell, which dates back to their first meeting in 1910. The two teams play twice annually.

In men's rugby, Harvard maintains a rivalry with McGill, as demonstrated by the biennial Harvard-McGill rugby games, alternately played in Montreal and Cambridge.[143]

Notable people

[edit]Alumni

[edit]Since its founding nearly four centuries ago, Harvard alumni have distinguished themselves in academia, activism, arts, athletics, business, entrepreneurship, government, international affairs, journalism, media, music, non-profit organizations, politics, public policy, science, technology, writing, and other industries and fields. A 2024 study analyzed the educational backgrounds of the most successful and influential Americans—"30 different achievement groups totaling 26,198 people"—and found that Harvard alumni were unusually dominant.[144] A 2025 study of 6,141 of the most influential people in the world discovered that Harvard alumni are massively overrepresented among the global elite, and that this finding remains true when all American elites are removed.[145]

Among the world's universities and colleges, Harvard has the most U.S. presidents (eight), living billionaires (188), Nobel laureates (162), Pulitzer Prize winners (48), Fields Medal recipients (seven), Marshall scholars (252), and Rhodes Scholars (369) among its alumni. Harvard alumni also include nine Turing Award laureates, ten Academy Awards winners, and 108 Olympic medalists, including 46 gold medal winners.[146][147][148][149][150][151]

- Notable Harvard alumni include:

-

2nd President of the United States John Adams (AB, 1755; AM, 1758)[152]

-

26th President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Theodore Roosevelt (AB, 1880)[155]

-

32nd President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt (AB, 1903)[156]

-

Poet and Nobel laureate in literature T. S. Eliot (AB, 1910; AM, 1911)[157]

-

Physicist and leader of the Manhattan Project J. Robert Oppenheimer (AB, 1925)

-

35th President of the United States John F. Kennedy (AB, 1940)[158]

-

15th Prime Minister of Canada Pierre Trudeau (MA, 1947)

-

24th President of Liberia and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (MPA, 1971)[159]

-

43rd President of the United States George W. Bush (MBA, 1975)[160]

-

17th Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts (AB, 1976; JD, 1979)

-

8th Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon (MPA, 1984)

-

24th Prime Minister of Canada Mark Carney (AB, 1988)[161]

-

44th President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Barack Obama (JD, 1991)[162][163]

-

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Ketanji Brown Jackson (AB,1992; JD, 1996)[164]

Faculty

[edit]- Notable past and present Harvard faculty include:

In popular culture

[edit]

Harvard's reputation as a center of elite achievement or elitist privilege has made it a frequent literary and cinematic backdrop. "In the grammar of film, Harvard has come to mean both tradition, and a certain amount of stuffiness," film critic Paul Sherman said in 2010.[165]

Literature

[edit]In contemporary literature, Harvard University features prominently in multiple novels, including:

- The Sound and the Fury (1929) and Absalom, Absalom! (1936), two novels by William Faulkner, both of which depict Harvard student life.[166]

- Of Time and the River (1935) by Thomas Wolfe, a fictionalized autobiography, depicting Wolfe's alter ego, Eugene Gant, a Harvard student.[167]

- The Late George Apley (1937), by 1915 Harvard alumnus John P. Marquand, a novel presenting a satirical view of Harvard men in the early 20th century,[167] which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[168]

- The Second Happiest Day (1953), by John P. Marquand, portrays Harvard during the World War II generation.[169][170][171][172][173]

Films

[edit]Harvard University features prominently in the plots of multiple major films, including:

- Love Story (1970), a romance between a wealthy Harvard ice hockey player, played by Ryan O'Neal, and a brilliant Radcliffe student of modest means, played by Ali MacGraw.[174][175][176]

- The Paper Chase (1973),[177] a drama based on the 1971 novel of the same name by Harvard alumnus John Jay Osborn Jr., about a first year Harvard Law School student facing a demanding contract law course and professor.

- A Small Circle of Friends (1980), a drama about three Harvard University students in the 1960s

- Prozac Nation (1994), a psychological drama starring Christina Ricci based on the novel of the same name by Elizabeth Wurtzel, which documents her real life story as a 19-year-old Harvard freshman struggling with substance abuse and clinical depression.

- Legally Blonde (2001), a comedy film starring Reese Witherspoon a blonde sorority girl who enrolls in Harvard Law School to get her ex-boyfriend back.

- Homeless to Harvard: The Liz Murray Story (2003), a Lifetime biographical television film, which chronicles the real life story of Liz Murray (played by Thora Birch), who overcomes homelessness and a dysfunctional family to gain entry and a scholarship to Harvard after winning a New York Times-sponsored essay competition.

- The Social Network (2010), a biographical drama film which portrays the founding of social networking website Facebook.

See also

[edit]- Academic regalia of Harvard University

- Gore Hall

- Harvard College social clubs

- Harvard University Police Department

- Harvard University Press

- Harvard/MIT Cooperative Society

- I, Too, Am Harvard

- List of Harvard University named chairs

- List of Nobel laureates affiliated with Harvard University

- List of oldest universities in continuous operation

- Outline of Harvard University

- Secret Court of 1920

Notes

[edit]- ^ Universities adopt different metrics to claim Nobel or other academic award affiliates, some generous while others more stringent.

"The official Harvard count, which is 49, only includes academicians affiliated at the time of winning the prize. Yet, the figure can be up to some 160 Nobel affiliates, the most worldwide, if visitors and professors of various ranks are all included (the most generous criterium), as what some other universities do". Archived from the original on March 22, 2023.- Rachel Sugar (May 29, 2015). "Where MacArthur 'Geniuses' Went to College". businessinsider.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- "Top Producers". us.fulbrightonline.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "US Rhodes Scholars Over Time". www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- "Harvard, Stanford, Yale Graduate Most Members of Congress". Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- "The complete list of Fields Medal winners". areppim AG. 2014. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ Records of The Tercentenary Festival of Dublin University. Dublin, Ireland: Hodges, Figgis & Co. 1894. ISBN 978-1-355-36160-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Anderson, Peter John (1907). Record of the Celebration of the Quatercentenary of the University of Aberdeen: From 25th to 28th September, 1906. Aberdeen, United Kingdom: Aberdeen University Press (University of Aberdeen). ISBN 978-1-363-62507-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (1968). The Founding of Harvard College. Harvard University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-674-31450-4. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ An appropriation of £400 toward a "school or college" was voted on October 28, 1636 (OS), at a meeting which convened on September 8 and was adjourned to October 28. Some sources consider October 28, 1636 (OS) (November 7, 1636, NS) to be the date of founding. Harvard's 1936 tercentenary celebration treated September 18 as the founding date, though its 1836 bicentennial was celebrated on September 8, 1836. Sources: meeting dates, Quincy, Josiah (1860). The History of Harvard University. Crosby, Nichols, Lee & Company. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-405-10016-1. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help), "At a Court holden September 8th, 1636 and continued by adjournment to the 28th of the 8th month (October, 1636)... the Court agreed to give £400 towards a School or College, whereof £200 to be paid next year...." Tercentenary dates: "Cambridge Birthday". Time. September 28, 1936. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2006.: "Harvard claims birth on the day the Massachusetts Great and General Court convened to authorize its founding. This was Sept. 8, 1637 under the Julian calendar. Allowing for the ten-day advance of the Gregorian calendar, Tercentenary officials arrived at Sept. 18 as the date for the third and last big Day of the celebration;" "on Oct. 28, 1636 ... £400 for that 'school or college' [was voted by] the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony." Bicentennial date: Marvin Hightower (September 2, 2003). "Harvard Gazette: This Month in Harvard History". Harvard University. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006., "Sept. 8, 1836 – Some 1,100 to 1,300 alumni flock to Harvard's Bicentennial, at which a professional choir premieres "Fair Harvard." ... guest speaker Josiah Quincy Jr., Class of 1821, makes a motion, unanimously adopted, 'that this assembly of the Alumni be adjourned to meet at this place on September 8, 1936.'" Tercentary opening of Quincy's sealed package: The New York Times, September 9, 1936, p. 24, "Package Sealed in 1836 Opened at Harvard. It Held Letters Written at Bicentenary": "September 8th, 1936: As the first formal function in the celebration of Harvard's tercentenary, the Harvard Alumni Association witnessed the opening by President Conant of the 'mysterious' package sealed by President Josiah Quincy at the Harvard bicentennial in 1836." - ^ Haidar, Emma H.; Kettles, Cam E. (March 1, 2024). "Harvard Law School Dean John Manning '82 Named Interim Provost by Garber". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on May 20, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "Harvard University Graphic Identity Standards Manual" (PDF). July 14, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Common Data Set 2024–2025" (PDF). Office of Institutional Research. Harvard University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2025. Retrieved July 18, 2025.

- ^ "IPEDS – Harvard University". Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ "Color Scheme" (PDF). Harvard Athletics Brand Identity Guide. July 27, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Examples include:

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–481. ISBN 0-19-514457-0.

Harvard's professional schools... won world prestige of a sort rarely seen among social institutions. [...] Harvard's age, wealth, quality, and prestige may well shield it from any conceivable vicissitudes.

- Spaulding, Christina (1989). "Sexual Shakedown". In Trumpbour, John (ed.). How Harvard Rules: Reason in the Service of Empire. South End Press. pp. 326–336. ISBN 0-89608-284-9.

... [Harvard's] tremendous institutional power and prestige [...] Within the nation's (arguably) most prestigious institution of higher learning ...

- David Altaner (March 9, 2011). "Harvard, MIT Ranked Most Prestigious Universities, Study Reports". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Collier's Encyclopedia. Macmillan Educational Co. 1986.

Harvard University, one of the world's most prestigious institutions of higher learning, was founded in Massachusetts in 1636.

- Newport, Frank (August 26, 2003). "Harvard Number One University in Eyes of Public Stanford and Yale in second place". Gallup. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- Leonhardt, David (September 17, 2006). "Ending Early Admissions: Guess Who Wins?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

The most prestigious college in the world, of course, is Harvard, and the gap between it and every other university is often underestimated.

- Hoerr, John (1997). We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard. Temple University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-56639-535-9.

- Wong, Alia (September 11, 2018). "At Private Colleges, Students Pay for Prestige". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

Americans tend to think of colleges as falling somewhere on a vast hierarchy based largely on their status and brand recognition. At the top are the Harvards and the Stanfords, with their celebrated faculty, groundbreaking research, and perfectly manicured quads.

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–481. ISBN 0-19-514457-0.

- ^ "Harvard Charter of 1650" Archived November 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Harvard Library

- ^ Story, Ronald (1975). "Harvard and the Boston Brahmins: A Study in Institutional and Class Development, 1800–1865". Journal of Social History. 8 (3): 94–121. doi:10.1353/jsh/8.3.94. ISSN 0022-4529. S2CID 147208647.

- ^ Farrell, Betty G. (1993). Elite Families: Class and Power in Nineteenth-Century Boston. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1593-7.

- ^ a b "Member Institutions and years of Admission". aau.edu. Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ "Faculties and Allied Institutions" (PDF). harvard.edu. Office of the Provost, Harvard University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "Faculties and Allied Institutions" (PDF). Office of the Provost, Harvard University. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Harvard posts investment gain in fiscal 2023, endowment stands at $50.7 billion". Reuters.com. October 20, 2023. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Financial Report Fiscal Year 2023 (PDF) (Report). Harvard University. October 19, 2023. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon (March 8, 2012). "The instrument behind New England's first literary flowering". harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Rowley and Ezekiel Rogers, The First North American Printing Press" (PDF). hull.ac.uk. Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Harvard, John. "John Harvard Facts, Information". encyclopedia.com. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

He bequeathed £780 (half his estate) and his library of 320 volumes to the new established college at Cambridge, Mass., which was named in his honor.

- ^ Wright, Louis B. (2002). The Cultural Life of the American Colonies (1st ed.). Dover Publications (published May 3, 2002). p. 116. ISBN 978-0-486-42223-7.

- ^ Grigg, John A.; Mancall, Peter C. (2008). British Colonial America: People and Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-59884-025-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Harvard Office of News and Public Affairs (July 26, 2007). "Harvard guide intro". Harvard University. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "John Leverett – History – Office of the President". Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Harvard's year of exile", The Harvard Gazette, October 13, 2011

- ^ University, Harvard. "Harvard and the American Revolution". Harvard University. Archived from the original on June 13, 2025. Retrieved June 13, 2025.

- ^ Driscoll, Timothy. "Research Guides: Harvard Presidential Insignia: Seals of 1650, 1843, and 1885". guides.library.harvard.edu. Retrieved April 15, 2025.

- ^ a b Dorrien, Gary J. (January 1, 2001). The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion, 1805–1900. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22354-0. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Field, Peter S. (2003). Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-8843-2. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Shoemaker, Stephen P. (2006–2007). "The Theological Roots of Charles W. Eliot's Educational Reforms". Journal of Unitarian Universalist History. 31: 30–45.

- ^ "An Iconic College View: Harvard University, circa 1900. Richard Rummell (1848–1924)". An Iconic College View. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Jerome Karabel (2006). The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-618-77355-8. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Compelled to coexist: A history of the desegregation of Harvard's freshman housing". Harvard Crimson. November 4, 2021. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022.

- ^ Steinberg, Stephen (September 1, 1971). "How Jewish Quotas Began". Commentary. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (March 4, 1986). "Yale's Limit on Jewish Enrollment Lasted Until Early 1960s Book Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Lowell Tells Jews Limits at Colleges Might Help Them". The New York Times. June 17, 1922. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Kridel, Craig, ed. (2010). "General Education in a Free Society (Harvard Redbook)". Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies. Vol. 1. SAGE. pp. 400–402. ISBN 978-1-4129-5883-7.

- ^ First class of women admitted to Harvard Medical School, 1945 (Report). Countway Repository, Harvard University Library. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ "The Class of 1950". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ Older, Malka A. (January 24, 1996). "Preparatory schools and the admissions process". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009.

- ^ Powell, Alvin (October 1, 2018). "An update on Harvard's diversity, inclusion efforts". The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Radcliffe Enters Historic Merger With Harvard (Report). Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ "Harvard Board Names First Woman President". NBC News. Associated Press. February 11, 2007. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Harvard University names Lawrence Bacow its 29th president". Fox News. Associated Press. February 11, 2018. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Quinn, Ryan (February 6, 2023). "Harvard Postdocs, Other Non-Tenure-Track Trying to Unionize". Inside Higher Education. Archived from the original on December 8, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ "HARVARD PRESIDENT CLAUDINE GAY RESIGNS, SHORTEST TENURE IN UNIVERSITY HISTORY". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "Meet the former Democrat leading Trump's charge against 10 universities". Politico. May 23, 2025.

- ^ a b Rose, Taylor Romine, Nouran Salahieh, Hanna Park, Andy (April 17, 2025). "DHS threatens to revoke Harvard's eligibility to host foreign students amid broader battle over universities' autonomy". CNN. Retrieved April 21, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moody, Josh (April 14, 2025). "Harvard Resists Trump's Demands". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved April 14, 2025.

- ^ "Trump officials cut billions in Harvard funds after university defies demands". The Guardian. April 14, 2025. Retrieved April 14, 2025.

- ^ Bhuiyan, Johana (April 21, 2025). "Harvard sues Trump administration over efforts to 'gain control of academic decision-making'". The Guardian. Retrieved April 21, 2025.

- ^ Grumbach, Gary; Stelloh, Tim (April 21, 2025). "Harvard sues federal government after Trump administration slashed billions in funding". NBC News. Retrieved April 21, 2025.

- ^ Speri, Alice (July 21, 2025). "Harvard argues in court that Trump administration's $2.6bn cuts are illegal". The Guardian. Retrieved July 21, 2025.

- ^ Mackey, Robert (May 5, 2025). "Trump blocks grant funding for Harvard until it meets president's demands". The Guardian. Retrieved May 6, 2025.

- ^ "Trump administration cuts another $450 million in grants for Harvard in escalating battle". NBC News. The Associated Press. May 13, 2025. Retrieved May 13, 2025.

- ^ Yang, Maya (May 22, 2025). "Trump administration halts Harvard's ability to enroll international students". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 24, 2025. Retrieved May 22, 2025.

- ^ "Harvard University Loses Student and Exchange Visitor Program Certification for Pro-Terrorist Conduct". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. May 22, 2025. Retrieved May 22, 2025.

- ^ Sainato, Michael (May 23, 2025). "Harvard University sues Trump administration over ban on enrolling foreign students". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 24, 2025. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ Betts, Anna (May 23, 2025). "Harvard v Trump: takeaways from university's legal battle over international student ban". The Guardian. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ "Harvard Visa Complaint" (PDF). Harvard University. May 23, 2025. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ Binkley, Collin (May 23, 2025). "Federal judge blocks Trump administration from barring foreign student enrollment at Harvard". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2025. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ Nadworny, Elissa; Piper-Vallillo, Emily (June 16, 2025). "Judge postpones decision in Harvard lawsuit against Trump over international students". NPR. Archived from the original on June 16, 2025. Retrieved June 16, 2025.

- ^ Gedeon, Joseph (May 30, 2025). "White House targets Harvard again with social media screening of all foreign visitors to school". The Guardian. Retrieved May 30, 2025.

- ^ Hawkins, Amy (June 5, 2025). "Trump signs proclamation to restrict foreign student visas at Harvard". The Guardian. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ Trump, Donald (June 4, 2025). "Enhancing National Security by Addressing Risks at Harvard University". The White House. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ Helsel, Phil (June 5, 2025). "Harvard files legal challenge to Trump's effort to block visas for international students". NBC News. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ "Harvard asks judge to immediately block Trump's ban on foreign students". The Guardian. Reuters. June 5, 2025. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ "President and Fellows of Harvard College v. United States Department of Homeland Security (1:25-cv-11472)". CourtListener. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ "Federal judge blocks Trump effort to keep Harvard from hosting foreign students". Associated Press News. June 20, 2025. Archived from the original on June 20, 2025. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ Nadworny, Elissa (June 30, 2025). "Federal investigation finds Harvard violated civil rights law". NPR. Retrieved June 30, 2025.

- ^ Voreacos, David (September 3, 2025). "Harvard $2 Billion Funding Freeze Found Illegal by US Judge". Bloomberg. Retrieved September 3, 2025.

- ^ Harvard College. "A Brief History of Harvard College". Harvard College. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "The Houses". Harvard College Dean of Students Office. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University". Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Institutional Ownership Map – Cambridge Massachusetts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Tartakoff, Joseph M.; Rubin-wills, Jessica R. (January 7, 2005). "Harvard Purchases Doubletree Hotel Building". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Logan, Tim (April 13, 2016). "Harvard continues its march into Allston, with science complex". BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Allston Planning and Development / Office of the Executive Vice President". harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Bayliss, Svea Herbst (January 21, 2007). "Harvard unveils big campus expansion". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ O'Rourke, Brigid (April 10, 2020). "SEAS moves opening of Science and Engineering Complex to spring semester '21". The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Our Campus". harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "Concord Field Station". mcz.harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Villa I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies". Itatti.it. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Shanghai Center". Harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; Shenton, Robert (2009). Harvard A to Z. Harvard University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-674-02089-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Burlington Free Press, June 24, 2009, page 11B, ""Harvard to cut 275 jobs" Associated Press

- ^ Office of Institutional Research (2009). Harvard University Fact Book 2009–2010 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011.("Faculty")

- ^ Heller, Nathan (March 3, 2025). "Will Harvard Bend or Break?". The New Yorker.

- ^ Vidya B. Viswanathan and Peter F. Zhu (March 5, 2009). "Residents Protest Vacancies in Allston". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Healy, Beth (January 28, 2010). "Harvard endowment leads others down". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Hechinger, John (December 4, 2008). "Harvard Hit by Loss as Crisis Spreads to Colleges". The Wall Street Journal. p. A1.

- ^ Munk, Nina (July 20, 2009). "Nina Munk on Hard Times at Harvard". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Andrew M. Rosenfield (March 4, 2009). "Understanding Endowments, Part I". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 19, 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "A Singular Mission". Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Admissions Cuts Concern Some Graduate Students". Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Financial Report" (PDF). harvard.edu. October 24, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Welton, Alli (November 20, 2012). "Harvard Students Vote 72 Percent Support for Fossil Fuel Divestment". The Nation. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Chaidez, Alexandra A. (October 22, 2019). "Harvard Prison Divestment Campaign Delivers Report to Mass. Hall". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b George, Michael C.; Kaufman, David W. (May 23, 2012). "Students Protest Investment in Apartheid South Africa". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Cadambi, Anjali (September 19, 2010). "Harvard University community campaigns for divestment from apartheid South Africa, 1977–1989". Global Nonviolent Action Database. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Robert Anthony Waters Jr. (March 20, 2009). Historical Dictionary of United States-Africa Relations. Scarecrow Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8108-6291-3. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Carnegie Classifications – Harvard University". iu.edu. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ a b "Liberal Arts & Sciences". harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Degree Programs" (PDF). Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Handbook. pp. 28–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ a b "Degrees Awarded". harvard.edu. Office of Institutional Research, Harvard University. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "The Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science Degrees". college.harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Academic Information: The Concentration Requirement". Handbook for Students. Harvard College. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ "How large are classes?". harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Harvard University Campus Information, Costs and Details". www.collegeraptor.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "Member Institutions and Years of Admission". Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ "2023 Best Medical Schools: Research". usnews.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ "Research at Harvard Medical School". hms.harvard.edu. Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ "Which schools get the most research money?". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "About Harvard Library", Harvard Library website

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2025". Forbes. September 6, 2025. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- ^ "2025-2026 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2025. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2025. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- ^ "2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2026". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 19, 2025. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2025". Times Higher Education. October 9, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "2025-2026 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 17, 2025. Retrieved June 17, 2025.

- ^ Massachusetts Institutions, New England Commission of Higher Education, archived from the original on August 17, 2021, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings 2016". Times Higher Education. 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Lombardi, John V.; Abbey, Craig W.; Craig, Diane D.; Collis, Lynne N. (2021). "The Top American Research Universities: 2023 Annual Report" (PDF). mup.umass.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2023.

- ^ "World Ranking". University Ranking by Academic Performance. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ "College Hopes & Worries Press Release" (Press release). The Princeton Review. 2016. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Princeton Review's 2012 "College Hopes & Worries Survey" Reports on 10,650 Students' & Parents' Top 10 "Dream Colleges" and Application Perspectives" (Press release). The Princeton Review. 2012. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "2019 College Hopes & Worries Press Release". 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Dickler, Jessica (March 5, 2024). "Harvard is back on top as college hopefuls' ultimate 'dream' school, despite recent turmoil". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 10, 2024. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ contact, Press (February 11, 2019). "Harvard is #3 in World University Engineering Rankings". Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "The Best International Relations Schools in the World". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "College Scorecard: Harvard University". College Scorecard. United States Department of Education. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2025.

- ^ "Harvard Students Vote Overwhelmingly to Dissolve Undergraduate Council in Favor of New Student Government | News | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a) Law School Student Government "Harvard Law School Student Government". Archived from the original on June 24, 2021.

b) School of Education Student Council "Student Council". Archived from the original on July 19, 2022.

c) Kennedy School Student Government "Student Government". Archived from the original on June 21, 2021.

d) Design School Student Forum "Student Forum". Archived from the original on June 14, 2021.

e) Student Council of Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Dental Medicine "HMS & HSDM Student Council | Harvard Medical School | United States". Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. - ^ "Harvard: Women's Rugby Becomes 42nd Varsity Sport at Harvard University". Harvard. Gocrimson.com. August 9, 2012. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ "The Harvard Guide: Financial Aid at Harvard". Harvard University. September 2, 2006. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "Colors". Identity Guide. Harvard University. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Harvard's All-Time National Championships" Archived September 9, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, Harvard Crimson website

- ^ Bracken, Chris (November 17, 2017). "A game unlike any other". yaledailynews.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Yale and Harvard Defeat Oxford/Cambridge Team". Yale. Yale University Athletics. April 10, 2009. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ "Ruggers Set For Rivalry; McGill Comes to Town | Sports | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ Wai, Jonathan; Anderson, Stephen M.; Perina, Kaja; Worrell, Frank C.; Chabris, Christopher F. (September 3, 2024). "The most successful and influential Americans come from a surprisingly narrow range of 'elite' educational backgrounds". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 11 1129. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-03547-8. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ Salas-Díaz, Ricardo; Young, Kevin L. (January 2025). "Where Did the Global Elite Go to School? Hierarchy, Harvard, Home and Hegemony". Global Networks. 25 (1) e12509. doi:10.1111/glob.12509.

- ^ Siliezar, Juan (November 23, 2020). "2020 Rhodes, Mitchell Scholars named". harvard.edu. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Communications, FAS (November 24, 2019). "Five Harvard students named Rhodes Scholars". The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Kathleen Elkins (May 18, 2018). "More billionaires went to Harvard than to Stanford, MIT and Yale combined". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize Winners". Harvard University. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Companies – Entrepreneurship – Harvard Business School". entrepreneurship.hbs.edu. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Barzilay, Karen N. "The Education of John Adams". Massachusetts Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "John Quincy Adams". The White House. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Hogan, Margaret A. (October 4, 2016). "John Quincy Adams: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Theodore Roosevelt - Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (October 4, 2016). "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Kirsch, Adam (June 16, 2015). "T.S. Eliot as a Harvard student | Harvard Magazine". www.harvardmagazine.com. Retrieved July 4, 2025.

- ^ Selverstone, Marc J. (October 4, 2016). "John F. Kennedy: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Ellen Johnson Sirleaf - Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ L. Gregg II, Gary (October 4, 2016). "George W. Bush: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "About | Prime Minister of Canada". Prime Minister of Canada. June 9, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2025.

- ^ "Barack Obama: Life Before the Presidency". Miller Center. October 4, 2016. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Barack H. Obama - Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ DeSmith, Christy (November 20, 2024). "Ketanji Brown Jackson rejoins Michael Sandel's 'Justice'". Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on May 25, 2025. Retrieved July 4, 2025.

- ^ Thomas, Sarah (September 24, 2010). "'Social Network' taps other campuses for Harvard role". Boston.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

'In the grammar of film, Harvard has come to mean both tradition, and a certain amount of stuffiness.... Someone from Missouri who has never lived in Boston ... can get this idea that it's all trust fund babies and ivy-covered walls.'

- ^ Crinkley, Richmond (July 12, 1962). "WILLIAM FAULKNER: The Southern Mind Meets Harvard In the Era Before World War I". www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Vaughan Bail, Hamilton (1958). "Harvard Fiction: Some critical and Bibliographical Notes" (PDF). American Antiquarian Society: 346–347. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "Late George Apley". Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ King, Michael (2002). Wrestling with the Angel. p. 371.

...praised as an iconic chronicle of his generation and his WASP-ish class.

- ^ Halberstam, Michael J. (February 18, 1953). "White Shoe and Weak Will". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015.

The book is written slickly, but without distinction.... The book will be quick, enjoyable reading for all Harvard men.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (December 23, 2009). "Second Reading". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015.

'...a balanced and impressive novel...' [is] a judgment with which I [agree].

- ^ Du Bois, William (February 1, 1953). "Out of a Jitter-and-Fritter World". The New York Times. p. BR5.

exhibits Mr. Phillips' talent at its finest

- ^ "John Phillips, The Second Happiest Day". Southwest Review. Vol. 38. p. 267.

So when the critics say the author of "The Second Happiest Day" is a new Fitzgerald, we think they may be right.

- ^ "Never Having To Say You're Sorry for 25 Years..." Harvard Crimson. June 3, 1996. Archived from the original on July 17, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (August 20, 2010). "The Disease: Fatal. The Treatment: Mockery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ "A Many-Splendored 'Love Story'". Harvard University Gazette. February 8, 1996.

- ^ Walsh, Colleen (October 2, 2012). "The Paper Chase at 40". Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abelmann, Walter H., ed. The Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology: The First 25 Years, 1970–1995 (2004). 346 pp.

- Beecher, Henry K. and Altschule, Mark D. Medicine at Harvard: The First 300 Years (1977). 569 pp.

- Bentinck-Smith, William, ed. The Harvard Book: Selections from Three Centuries (2d ed.1982). 499 pp.

- Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; and Shenton, Robert. Harvard A to Z (2004). 396 pp. excerpt and text search

- Bethell, John T. Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-674-37733-8

- Bunting, Bainbridge. Harvard: An Architectural History (1985). 350 pp.

- Carpenter, Kenneth E. The First 350 Years of the Harvard University Library: Description of an Exhibition (1986). 216 pp.

- Cuno, James et al. Harvard's Art Museums: 100 Years of Collecting (1996). 364 pp.

- Elliott, Clark A. and Rossiter, Margaret W., eds. Science at Harvard University: Historical Perspectives (1992). 380 pp.

- Hall, Max. Harvard University Press: A History (1986). 257 pp.

- Hay, Ida. Science in the Pleasure Ground: A History of the Arnold Arboretum (1995). 349 pp.

- Hoerr, John, We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard; Temple University Press, 1997, ISBN 1-56639-535-6

- Howells, Dorothy Elia. A Century to Celebrate: Radcliffe College, 1879–1979 (1978). 152 pp.

- Keller, Morton, and Phyllis Keller. Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University (2001), major history covers 1933 to 2002 "online edition". Archived from the original on July 2, 2012.

- Lewis, Harry R. Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education (2006) ISBN 1-58648-393-5

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. Three Centuries of Harvard, 1636–1936 (1986) 512pp; excerpt and text search

- Powell, Arthur G. The Uncertain Profession: Harvard and the Search for Educational Authority (1980). 341 pp.

- Reid, Robert. Year One: An Intimate Look inside Harvard Business School (1994). 331 pp.

- Rosovsky, Henry. The University: An Owner's Manual (1991). 312 pp.

- Rosovsky, Nitza. The Jewish Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe (1986). 108 pp.

- Seligman, Joel. The High Citadel: The Influence of Harvard Law School (1978). 262 pp.

- Sollors, Werner; Titcomb, Caldwell; and Underwood, Thomas A., eds. Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-American Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe (1993). 548 pp.

- Trumpbour, John, ed., How Harvard Rules. Reason in the Service of Empire, Boston: South End Press, 1989, ISBN 0-89608-283-0

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, ed., Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. 337 pp.

- Winsor, Mary P. Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum (1991). 324 pp.

- Wright, Conrad Edick. Revolutionary Generation: Harvard Men and the Consequences of Independence (2005). 298 pp.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Harvard University at College Navigator, a tool from the National Center for Education Statistics

Harvard University

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding and Colonial Era