Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Federalism.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Federalism

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Federalism

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

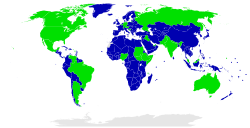

Federalism is a constitutional arrangement in which sovereign power is divided between a central government and subnational entities, such as states or provinces, with each level exercising direct authority over citizens within the same territory.[1][2] This division ensures that the central authority handles matters of national scope, like defense and foreign affairs, while subnational units retain autonomy over local concerns, including education and law enforcement, fostering a balance that prevents the concentration of power.[3][4]

The modern federal model emerged in the United States through the 1787 Constitutional Convention, where delegates addressed the Articles of Confederation's failures—such as inadequate central coordination during events like Shays' Rebellion—by creating a more robust union without fully eroding state sovereignty.[5] This framework, enshrined in the Supremacy Clause and the Tenth Amendment, has influenced systems in countries like Canada, Australia, Germany, and India, adapting to diverse cultural and geographic contexts.[2][6]

Federalism's defining characteristics include a written constitution delineating powers, bicameral legislatures often representing both population and regional equality, and independent judiciaries to arbitrate disputes, enabling policy experimentation across jurisdictions that empirical studies link to innovations in areas like welfare and environmental regulation.[4] Proponents argue it disperses authority to safeguard liberty and accommodate regional differences, as evidenced by states serving as "laboratories of democracy," while controversies arise from tendencies toward centralization—observed in U.S. fiscal transfers exceeding $700 billion annually—and intergovernmental conflicts, such as during the COVID-19 response where state variances highlighted both adaptive flexibility and coordination challenges.[7][8]

Symmetric models prioritize causal uniformity in power distribution to sustain long-term institutional stability, evidenced by lower secessionist movements in symmetric federations like Germany (no major post-WWII Länder exit attempts) compared to asymmetric ones.[110] Asymmetric arrangements, while empirically aiding short-term conflict mitigation—such as Russia's 1990s bilateral treaties stabilizing ethnic republics amid economic collapse—often escalate demands for further devolution, with data from 20th-century cases showing 30% higher amendment frequencies to address imbalances.[111][113] Transitioning between types proves challenging; for instance, India's partial symmetrization via 2019 Jammu and Kashmir reorganization integrated it as a union territory, reducing prior asymmetries but sparking legal challenges upheld by the Supreme Court in December 2023.[108] Overall, symmetric federalism aligns with first-principles of equal sovereignty to minimize rent-seeking, whereas asymmetry trades equity for pragmatic accommodation, with outcomes hinging on enforceable constitutional limits.[112]

Confederal systems often exhibit coordination inefficiencies, as seen in the European Union's pre-Lisbon Treaty era (before 2009) where veto powers hampered common policies, contrasting federalism's compulsory mechanisms like U.S. Supreme Court rulings binding states since 1803's Marbury v. Madison.[117] Unitary governments enable swift policy uniformity, such as the UK's centralized response to the 2008 financial crisis via national fiscal acts, but empirical studies show no consistent superiority over federal systems in economic growth or public goods provision, with federal arrangements sometimes fostering subnational innovation through competition.[115][118] Federalism's rigid division mitigates central overreach but introduces veto points that can delay responses, unlike unitary flexibility; confederalism's looseness, however, historically correlates with instability, as the Articles' inability to fund a national army contributed to their replacement in 1789.[119]

Definition and Core Principles

Definition and Etymology

Federalism denotes a constitutional arrangement of government in which sovereign power is divided between a central authority and semi-autonomous constituent units, such as states or provinces, with each level exercising exclusive authority in designated spheres while sharing others.[1][2] This division typically arises from a compact or agreement among the units, enabling coordinated action on national matters like defense and foreign affairs alongside local autonomy in areas such as education and law enforcement.[6] Unlike unitary systems, where subnational entities derive power solely from the center, federalism constitutionally entrenches the independence of both levels, preventing unilateral dominance by either.[3] The term "federal" originates from the Latin foedus, signifying a treaty, pact, covenant, or league, evoking alliances formed through mutual agreement rather than conquest or central fiat.[9][6] "Federalism" as a noun entered English usage around 1787, initially describing doctrines favoring union under a federal government, particularly in debates over the proposed U.S. Constitution and the positions of the Federalist advocates.[10] This etymology underscores federalism's roots in voluntary compacts among polities, distinguishing it conceptually from hierarchical or absolutist governance models.[11]First-Principles Rationale

Federalism rests on the foundational observation that human societies exhibit inherent tendencies toward factionalism and abuse of concentrated authority, necessitating a division of sovereign powers to safeguard liberty and promote effective rule. As James Madison argued in Federalist No. 10, a federal union extends the scale of republican government beyond small democracies prone to majority tyranny, allowing diverse interests to be diluted across a larger republic while retaining local governance to check centralized overreach. This vertical separation mirrors Montesquieu's horizontal separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers, designed to prevent any single entity from wielding unchecked dominion, as unchecked power invariably corrupts due to the self-interested nature of rulers.[12] A further principle is the mismatch between centralized decision-making and the dispersed, tacit knowledge required for adaptive governance. Centralized authorities lack the localized insights needed to address varied regional conditions, leading to inefficient or mismatched policies, whereas federal structures enable subnational units to apply proximate knowledge, fostering responsiveness without requiring omniscience from a distant center.[13] This epistemic rationale underscores federalism's utility in heterogeneous polities, where uniform national edicts would impose costs from ignoring diversity in preferences, geography, and culture.[4] Finally, federalism harnesses competitive dynamics among autonomous jurisdictions, incentivizing innovation and fiscal restraint akin to market mechanisms, as units vie for population and resources; failure to deliver prompts exit via migration, enforcing accountability absent in monolithic states.[14] This principle counters the stasis of unitary systems, where monopoly power stifles experimentation and entrenches inefficiency.[15]Historical Development

Ancient and Medieval Precursors

In ancient Greece, federal leagues emerged as mechanisms for city-states and ethnic groups to pool resources for mutual defense and diplomacy while retaining substantial local autonomy, marking early experiments in decentralized governance. The Aitolian League, active from the late 5th century BCE, integrated diverse tribes through federal assemblies like the Thermika (spring meetings) and Panaitolika (pan-Aitolian gatherings), fostering urban development and collective foreign policy without erasing internal tribal identities.[16] Similarly, the Achaian League, attested before 389 BCE and revitalized in the Hellenistic era, featured a federal assembly with proportional voting based on city populations, enabling trans-tribal cooperation that balanced centralized decision-making with member sovereignty.[16] The Akarnanian League, spanning the late 5th to 4th centuries BCE, subdivided representation among poleis and ethnē proportionally, providing a model for regional unification that influenced later federal thought by prioritizing collective security over absorption into a unitary state.[16] These Greek koina (federal commonwealths) proliferated in the 4th century BCE, including the Boiotian, Thessalian, and Arkadian Leagues, which harnessed combined military and economic strengths to counter hegemonic powers like Athens, Sparta, and later Macedon, often achieving trans-regional influence before succumbing to imperial expansion.[16] In the Roman Republic, from 509 BCE onward, confederal elements appeared in the alliance system with Italian socii (allies), where communities retained self-governance, local laws, and military obligations in exchange for Roman protection, forming a loose network under a central authority that prefigured federal bargaining but gradually centralized under expanding imperium.[17] Medieval Europe saw precursors in the Old Swiss Confederacy, formalized by the Federal Charter of 1291, which united the Alpine valleys of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden in a defensive pact against Habsburg overlords, emphasizing perpetual alliance, mutual aid, and preservation of cantonal independence in internal affairs.[18] This evolved through accessions, such as Lucerne in 1332 and Zurich in 1351, into a durable confederation prioritizing collective foreign policy over subordination.[19] The Holy Roman Empire, reestablished in 962 CE by Otto I, exhibited federalistic evolution from its Carolingian roots, transforming into a decentralized composite where over 300 semi-autonomous territories—principalities, ecclesiastical states, and imperial cities—elected the emperor, negotiated taxes, and convened in the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) for legislative consent, blending monarchical oversight with regional veto powers.[20][21] These structures highlighted causal tensions between coordination needs and autonomy, often enduring longer than ancient counterparts due to feudal fragmentation and elective mechanisms, though prone to paralysis in crises.[20]Enlightenment-Era Foundations

The Enlightenment era laid theoretical groundwork for federalism by conceptualizing decentralized governance as a safeguard for liberty in large polities, drawing on historical precedents to advocate compounded republics over unitary or purely confederate forms. Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, articulated this in The Spirit of the Laws (1748), where he described confederate republics—societies of societies—as mechanisms uniting the internal virtues of small republics (such as civic virtue and moderation) with the external strength of monarchies to repel conquest.[22] In Book IX, Montesquieu posited that such arrangements allow member states to retain sovereign authority over internal affairs while ceding limited powers to a collective body for mutual defense and foreign relations, thereby mitigating the perils of scale that undermine simple republics, as evidenced in his analysis of the Lycian League (circa 168 BCE), Achaean League (circa 280–146 BCE), and the Helvetic Confederacy (established 1291, enduring into the 18th century).[23] He contended that confederacies composed of homogeneous republics foster concord and prevent aristocratic dominance, though they require vigilant preservation of member equality to avoid dissolution into empire or anarchy.[24] Montesquieu's framework emphasized causal mechanisms: geographic extent demands division of sovereignty to curb despotism, with federal bonds providing security without eroding local autonomy, a principle rooted in empirical observation of European and ancient systems rather than abstract idealism.[25] This resonated with Enlightenment commitments to balanced power, influencing subsequent debates by highlighting federalism's potential to reconcile republicanism with territorial ambition, though Montesquieu warned of inherent tensions, such as the risk of central overreach if defensive alliances evolve into offensive leagues.[26] David Hume advanced complementary ideas in his essay "Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth" (first published 1752), proposing a multi-tiered structure for extensive nations to achieve stable republican governance. Hume envisioned subdividing a realm into 100 counties, each with annually elected assemblies of 100–200 members handling local legislation, which in turn select deputies for provincial bodies and a national parliament for war, diplomacy, and trade—effectively a proto-federal hierarchy to diffuse factional strife and administrative overload.[27] He argued this devolution counters the "imbecility" of distant central rule, enabling enlightened self-interest to align with public good through proximate representation, while short terms and rotation prevent entrenched elites.[28] Hume's model, informed by British parliamentary evolution and continental examples, underscored federalism's pragmatic utility in fostering deliberation over passion, though he acknowledged implementation challenges in non-homogeneous societies.[29]19th and 20th Century Expansions

In the mid-19th century, Switzerland transitioned from a loose confederation to a federal state following the Sonderbund War of 1847, which pitted Catholic conservative cantons against liberal reformers; the resulting Federal Constitution of September 12, 1848, centralized certain powers such as defense and foreign affairs while preserving cantonal autonomy in education, religion, and local governance. This model balanced unity with diversity in a multilingual, multi-confessional society, influencing later European federal experiments.[30] Canada's adoption of federalism occurred through the British North America Act of 1867, which united the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick into the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867, dividing powers between the federal government (responsible for trade, defense, and currency) and provinces (handling property, civil rights, and education).[31] This structure addressed regional differences, particularly linguistic and religious divides between English and French populations, while maintaining ties to the British Crown.[32] In Germany, the unification under the German Empire in 1871 established a federal system via the Constitution of April 16, 1871, where 25 states and free cities retained significant sovereignty in internal affairs, but the Prussian-dominated federal government controlled foreign policy, military, and customs; this asymmetric federalism prioritized national consolidation amid post-Napoleonic fragmentation.[33] The 20th century saw federalism expand to former colonies and diverse polities. Australia federated on January 1, 1901, when six self-governing British colonies united under the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, creating a federal division of powers that assigned defense, immigration, and external affairs to the national government while reserving residual powers like education and health to states.[34] This arrangement resolved inter-colonial rivalries over trade barriers and defense needs, fostering economic integration without erasing state identities.[35] India's Constitution, effective January 26, 1950, incorporated federal elements by designating the country as a "Union of States" with a bicameral Parliament, an upper house representing states, and enumerated lists dividing legislative powers (Union List for national matters like defense, State List for local issues like police, and Concurrent List for shared areas). However, provisions allowing the center to override states during emergencies and reorganize boundaries reflected a quasi-federal design suited to integrating princely states and diverse regions post-independence, prioritizing national cohesion over strict decentralization.[36] These expansions often adapted the American federal prototype to local exigencies, such as ethnic heterogeneity or imperial legacies, but empirical outcomes varied; for instance, Germany's federalism facilitated industrialization yet sowed seeds for centralizing authoritarianism by 1918, while Australia's emphasized competitive state policies driving post-federation growth.[37] By mid-century, over a dozen new federal systems emerged in decolonizing regions, though many, like Nigeria's 1960 constitution, faced challenges from ethnic tensions leading to unitaristic shifts.[37]Theoretical Foundations

Political Philosophy Underpinning Federalism

The political philosophy of federalism emphasizes dividing sovereignty between central authorities and constituent units to mitigate the risks of concentrated power, drawing from Enlightenment conceptions of limited government and human fallibility. Rooted in social contract theory, as articulated by John Locke in Two Treatises of Government (1689), it posits that legitimate authority arises from consent to protect natural rights, requiring structural constraints to prevent rulers from encroaching on liberties, with federal arrangements extending this logic beyond simple separation of branches to multiple jurisdictional layers.[38] Charles de Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws (1748), further developed this by advocating federal republics for large nations, arguing that confederated systems combine the liberty-preserving virtues of small republics—such as citizen vigilance—with the stability of monarchical oversight, thereby averting despotism in expansive territories where uniform central rule would prove oppressive.[26][39] Preceding these, Johannes Althusius laid foundational ideas in Politica Methodice Digesta (1603), conceiving politics as a covenantal federation of voluntary associations—from families to provinces—where higher polities intervene only to support, not supplant, lower ones, embodying a principle of subsidiarity that reserves authority to the most proximate effective level to foster mutual aid and resist absolutism.[40] This associational model countered monarchical centralization by grounding legitimacy in consensual pacts, influencing subsequent federal thought by prioritizing decentralized consent over hierarchical sovereignty.[41] American federalism's philosophy crystallized in The Federalist Papers (1787–1788), where James Madison argued in No. 10 that extending the republic federally dilutes factional perils—self-interested groups that dominate smaller polities—by multiplying competing interests across diverse units, rendering uniform injustice improbable as "a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project" dissipates in a broader union.[22] In No. 51, Madison elaborated that federalism supplements internal checks with inter-level divisions, observing that "in republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates," but a compound structure where states check the center and vice versa enforces accountability, as "ambition must be made to counteract ambition" to secure rights without relying on virtuous angels.[22] Alexander Hamilton, in No. 9, reinforced this by citing Montesquieu's endorsement of ancient confederacies like the Achaean League, which federal bonds rendered resilient against dissolution, proving that properly constituted unions harmonize local autonomy with national vigor.[22] These arguments rest on causal realism regarding governance: undivided power invites abuse due to rulers' incentives to expand control, whereas federal diffusion aligns authority with heterogeneous interests, enabling localized adaptation and experimentation while curbing overreach through competitive oversight, as evidenced in stable federations outperforming unitary alternatives in sustaining liberty amid diversity.[22]Economic Models and Decentralization

Fiscal federalism theory posits that economic efficiency in public goods provision is enhanced by assigning responsibilities to the governmental level closest to affected populations, balancing local preference heterogeneity against externalities and scale economies. Wallace Oates formalized this in his 1972 work, articulating the decentralization theorem: absent interjurisdictional spillovers, decentralized provision allows jurisdictions to tailor outputs to local tastes, minimizing mismatch costs compared to uniform central mandates.[42] This framework underpins models where subnational competition drives fiscal discipline, as mobile factors like capital and labor respond to tax and spending variations, pressuring inefficient policies toward correction.[43] The Tiebout model (1956) extends this by envisioning interjurisdictional mobility as a market-like mechanism for local public goods, where individuals "vote with their feet" by relocating to communities aligning with their willingness to pay, fostering efficient, preference-revealing equilibria under assumptions of perfect information, no spillovers, and numerous small jurisdictions.[44] In federal systems, this sorting promotes fiscal equivalence—equating tax prices to marginal benefits—and curbs free-riding, though real-world frictions like moving costs and income constraints limit full realization.[45] Empirical extensions, such as capitalization of local fiscal attributes into property values, provide indirect evidence of Tiebout effects in U.S. metropolitan areas, where housing premiums reflect amenities and taxes.[46] Competitive federalism amplifies these dynamics, treating subnational units as rivals in policy experimentation, akin to economic laboratories where successes (e.g., low-regulation growth hubs) diffuse via emulation or migration, while failures self-correct through capital flight.[47] Second-generation fiscal federalism incorporates political incentives, emphasizing that decentralization's gains hinge on institutional safeguards against soft budget constraints or pork-barrel capture, where central bailouts undermine local accountability.[48] For instance, revenue autonomy correlates with restrained spending in well-structured federations, contrasting with overborrowing in poorly coordinated ones.[49] Cross-country analyses reveal mixed but conditionally positive economic outcomes from decentralization. In federal developing nations, both expenditure and tax revenue decentralization boosted GDP growth by 0.5-1% annually in panels from 1990-2015, attributed to localized investment responsiveness, though unitary counterparts lagged without such flexibility.[50] Revenue decentralization specifically enhances growth in high-governance environments, reducing disparities via competition, as seen in OECD regions where subnational fiscal independence halved inequality gaps post-1990 reforms.[51] However, benefits attenuate with weak rule of law, where decentralization can exacerbate corruption or uneven development, underscoring that institutional quality mediates causal links rather than decentralization alone driving prosperity.[52]Empirical Strengths and Successes

Key Advantages in Governance and Innovation

Federalism facilitates policy experimentation at subnational levels, enabling jurisdictions to test innovative approaches tailored to local conditions, which can then diffuse to others if successful. This "laboratories of democracy" dynamic, articulated by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in 1932, incentivizes competition among states or provinces to develop effective governance solutions, such as varying tax regimes or regulatory frameworks that address diverse economic needs.[53] Empirical analysis of Swiss cantons demonstrates that competitive federalism—characterized by fiscal autonomy and inter-jurisdictional rivalry—significantly enhances economic performance, with decentralized policies correlating to higher GDP growth rates compared to more cooperative arrangements.[54] In governance, federal structures promote accountability by aligning policies closer to citizens' preferences, reducing the inefficiencies of centralized decision-making that often ignore regional variations. Cross-national data from 73 countries (1965–2000) indicate that federal democracies exhibit 43% higher output per worker than unitary democracies, attributed to stronger property rights protection and policy decentralization that curbs corruption by 28% relative to unitary systems.[55] Fiscal decentralization further bolsters this by allowing subnational governments to prioritize developmental investments over redistributive spending, as evidenced in U.S. states where greater local fiscal control correlates with improved public service efficiency and responsiveness.[56] For innovation, federalism's division of powers fosters entrepreneurial governance, where subnational units compete to attract businesses and talent through customized incentives, leading to higher regional innovation outputs. Studies on fiscal decentralization across regions show a positive effect on innovation levels, with decentralized systems increasing patent applications and technological advancement by enabling targeted R&D funding and regulatory experimentation.[57] In federal democracies, this competitive environment contributes to superior economic dynamism, as seen in output metrics outperforming unitary counterparts by leveraging localized knowledge for adaptive problem-solving.[55]Evidence from Comparative Outcomes

Empirical comparisons of federal and unitary systems reveal that fiscal decentralization in federal structures correlates with enhanced economic growth. A 2020 cross-country analysis of developing nations demonstrated that in federal systems, greater decentralization of tax revenue and expenditure authorities leads to statistically significant positive effects on GDP growth rates, with coefficients indicating up to 0.5-1% additional annual growth per standard deviation increase in decentralization indices.[50] This outcome stems from subnational competition incentivizing efficient resource allocation and policy experimentation, contrasting with unitary systems where centralized decisions may stifle local adaptation. Endogenous growth models further support this, positing that interjurisdictional rivalry in federal setups amplifies human capital investment and productivity gains.[58] In innovation metrics, federal systems exhibit superior performance through "laboratory federalism," where states or provinces serve as testing grounds for policies that scale nationally upon success. U.S. historical data shows over 25% of major public-sector innovations originating at the state level before federal adoption, fostering adaptability absent in unitary frameworks prone to uniform policy imposition.[59] Comparative indices, such as the Global Innovation Index, consistently rank federal nations like the United States (ranked 3rd in 2023) and Switzerland (1st) above many unitary counterparts, attributing this to decentralized R&D funding and regulatory diversity that encourages entrepreneurial risk-taking. Governance outcomes in federal systems demonstrate advantages in managing diversity and resilience. Bayesian model averaging across global datasets reconciles prior ambiguities, affirming a positive association between federalism and long-term economic performance, particularly in heterogeneous societies where unitary centralization risks inefficiency.[60] For instance, federal Germany's post-WWII Wirtschaftswunder achieved average annual GDP growth of 8% from 1950-1960 through Länder-level industrial policies, outpacing unitary France's 5.1% in the same period, highlighting how divided powers enable targeted reforms. These patterns hold despite methodological challenges in isolating federalism from confounders like resource endowments, underscoring causal mechanisms of competition over mere correlation.Criticisms, Weaknesses, and Failures

Inherent Challenges and Coordination Issues

Federal systems inherently face challenges arising from the division of authority between central and subnational governments, which can result in overlapping jurisdictions and duplicated efforts across levels. This duplication often manifests as multiple governments addressing similar policy areas, such as environmental regulation or public health, leading to redundant administrative structures and increased costs without commensurate benefits. For instance, in the United States, federal and state agencies have separately developed programs for economic development, contributing to fragmented service delivery and higher taxpayer burdens.[61][62] Such inefficiencies stem from the structural need for each level to assert its enumerated powers, even when economies of scale favor centralized action.[63] A core coordination issue involves managing interjurisdictional spillovers, where actions in one unit affect others, necessitating mechanisms like intergovernmental councils or negotiated agreements that are prone to delays and political bargaining. In increasingly interdependent economies, policies on trade, migration, or pollution generate externalities that single units cannot internalize, risking suboptimal outcomes without effective horizontal or vertical coordination.[64] This is exacerbated by competitive federalism, which can induce a "race to the bottom" in regulatory standards—such as lax environmental or labor rules to attract businesses—undermining collective welfare as units prioritize local gains over national efficiency. Empirical analyses of decentralized regulation confirm such dynamics, where states lower standards inefficiently to compete, absent federal overrides.[65][66] Vertical fiscal imbalances represent another structural vulnerability, where subnational governments bear substantial spending responsibilities but possess limited own-source revenues, fostering dependency on central transfers and potential moral hazard in budgeting. In many federations, constitutions assign progressive taxes like income tax predominantly to the center, while devolving services like education and health to regions, creating gaps that transfers only partially bridge and often politicize.[67][68] This imbalance can lead to subnational overspending or underinvestment, as regions exploit federal funding without full accountability, with studies across advanced federations showing correlations between high VFI and elevated debt accumulation.[69] Coordination failures amplify during crises; for example, the U.S. response to COVID-19 highlighted acute intergovernmental discord, with states pursuing divergent strategies amid federal resource allocation disputes, contrasting somewhat smoother alignments in Canada and Australia due to stronger council mechanisms.[70][71] These patterns underscore federalism's causal tension: empowering subunits enhances responsiveness but complicates unified action, demanding robust institutions that real-world politics often undermine.[72]Empirical Cases of Underperformance

Federal systems have demonstrated underperformance in crisis response due to coordination challenges between national and subnational governments, as evidenced by the U.S. response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The storm caused over 1,800 deaths and $125 billion in damages, with delays in federal aid stemming from ambiguities in the National Response Plan, which required state requests before federal intervention, leading to a 48-hour lag in deploying active-duty troops despite President Bush's offers.[73] Local and state officials in Louisiana cited insufficient federal pre-positioning of resources, while federal agencies like FEMA faced internal disorganization, exacerbating a breakdown where supplies were blocked and evacuations stalled.[74] A congressional investigation attributed these failures to unclear lines of authority inherent in layered federal-state responsibilities, rather than solely resource shortages.[75] Similar coordination deficits appeared during the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic from 2020–2022, where federalism contributed to fragmented public health measures and excess mortality. States implemented divergent policies on lockdowns, mask mandates, and vaccine distribution, resulting in interstate travel risks and uneven economic recovery; for instance, federal guidelines were often ignored, leading to over 1 million deaths amid disputes over ventilator allocation.[76] Empirical analysis shows federal systems exhibited slower policy adaptation compared to unitary counterparts, with U.S. states' autonomy hindering national-scale testing and procurement, as procurement competition drove up costs by 20–50% for PPE.[70] Polarization amplified gridlock, with partisan governors resisting federal directives, correlating with higher case rates in non-cooperative states per CDC data.[77] In Argentina, fiscal federalism has perpetuated economic instability through subnational overspending and bailout expectations, fueling recurrent crises. Provinces, reliant on federal coparticipation transfers comprising 70% of their revenue, have accumulated debts exceeding 10% of GDP since the 1990s, prompting multiple defaults like the 2001 collapse that shrank GDP by 11%.[78] Empirical studies link this to perverse incentives where governors deficit-spend knowing national bailouts follow, as in 2018–2020 when provincial borrowing surged 40% amid federal fiscal rigidities, distorting national monetary policy.[79] Comparative data indicate Argentina's federal structure correlates with higher fiscal volatility than unitary Latin American peers, with intergovernmental bargaining delaying reforms and inflating public debt to 90% of GDP by 2023.[80] These patterns reflect vertical imbalances where expenditure devolution outpaces revenue autonomy, empirically worsening macroeconomic performance.[81]Constitutional and Institutional Mechanisms

Division of Powers and Enumerated Rights

In federal systems, constitutions establish a vertical division of powers between central and subnational governments to allocate authority over distinct spheres, promoting autonomy while enabling coordinated action on shared concerns. Central governments typically hold enumerated powers—explicitly listed competencies such as national defense, foreign affairs, and monetary policy—while subnational entities retain residual powers over unassigned matters like local governance and education.[4] This enumeration limits central overreach, as unlisted powers default to subnational levels unless concurrent arrangements apply.[82] Supremacy clauses in federal constitutions resolve conflicts, granting central laws precedence in overlapping areas, though judicial review ensures adherence to the enumerated framework.[4] Variations in allocation reflect historical and structural contexts. In the United States, Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution enumerates 18 specific federal powers, including taxing, regulating commerce among states, and coining money, with the Tenth Amendment reserving non-delegated powers to states or the people.[83] Canada's Constitution Act, 1867, uses dual lists: section 91 enumerates federal powers (e.g., trade and commerce, criminal law), section 92 assigns provincial powers (e.g., municipal institutions, civil rights), and section 95 designates concurrent fields like agriculture where federal law prevails.[84][85] Germany's Basic Law, Article 70 onward, defines exclusive federal powers (e.g., defense under Article 73), concurrent powers (e.g., civil law, where Länder legislate only if the federation refrains), and residual state competencies, with federal enabling laws sometimes delegating implementation.[86] Enumerated rights in federal constitutions specify protections for individuals against governmental infringement by either level, ensuring baseline liberties amid decentralized authority. These include freedoms of expression, religion, and assembly, often binding centrally and incorporated to subnational jurisdictions via judicial doctrine.[87] In the U.S., the Bill of Rights lists such rights, with the Ninth Amendment clarifying that enumeration does not negate others retained by the people, thus preserving unlisted liberties like privacy against federal and state actions.[88] Similar provisions appear in Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), enumerating rights like equality and legal rights applicable nationwide, subject to reasonable limits, while Germany's Basic Law Articles 1-19 outline inviolable human dignity and freedoms enforceable by the Federal Constitutional Court.[84] This enumeration fosters accountability, as violations trigger judicial nullification, though enforcement varies by interpretive approaches—originalist in some U.S. rulings versus evolving standards in others.[89] Constitutional mechanisms often include concurrent powers for efficiency, such as environmental regulation or health, but require intergovernmental coordination to avoid deadlock; for instance, India's Seventh Schedule lists union, state, and concurrent powers, with residuum to the center.[4] Dispute resolution via apex courts, like the U.S. Supreme Court interpreting enumerated bounds in cases such as McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), upholds the division while adapting to modern exigencies without eroding core enumerations.[82] Empirical data from federations show this structure correlates with lower central corruption indices when judicial independence is strong, as subnational competition incentivizes restraint.[4]Fiscal and Intergovernmental Relations

Fiscal relations in federal systems center on the assignment of taxing powers, expenditure responsibilities, and resource transfers to align incentives and ensure efficient public good provision. Central governments typically retain authority over broad-based, buoyant revenue sources such as personal income taxes, corporate taxes, and customs duties, which facilitate macroeconomic stabilization and redistribution, while subnational governments are assigned narrower taxes like property, sales, and excises suited to local conditions. This division stems from principles of fiscal efficiency, where taxing where costs are felt minimizes distortions, but often results in subnational entities bearing significant spending on devolved functions like education and infrastructure without matching revenue autonomy.[90][91] Vertical fiscal imbalance arises when subnational expenditures exceed own-source revenues, a common feature in federations where lower-tier governments handle 40-60% of total public spending but generate only 20-40% of revenues, necessitating upward fiscal flows via transfers. These imbalances, measured as the gap between subnational revenue and expenditure shares of GDP, averaged around 15 percentage points in OECD federal countries from 1995 to 2019, with transfers comprising block grants for general fiscal capacity and conditional grants tying funds to specific uses like matching infrastructure investments. Revenue-sharing formulas, often formula-based to reduce political discretion, allocate portions of central taxes—such as 20-50% of value-added tax proceeds in some systems—directly to subnationals, promoting accountability while centralizing collection for administrative efficiency.[92][93] Horizontal fiscal imbalances, reflecting disparities in subnational fiscal capacities due to resource endowments or economic bases, are mitigated through equalization transfers that redistribute from richer to poorer units without undermining incentives for growth. In practice, such programs—financed from central surpluses or shared revenues—aim to equalize per capita revenues to a national standard, as seen in systems where formulas incorporate population, tax effort, and needs-based adjustments; empirical analysis shows they reduce inequality in service provision but can entrench dependencies if not paired with borrowing limits.[91][93] Intergovernmental mechanisms facilitate coordination and dispute resolution in fiscal matters, including fiscal councils or inter-jurisdictional bodies that negotiate transfer volumes, monitor compliance, and enforce rules against excessive subnational debt. For instance, hard budget constraints—via no-bailout clauses or market discipline on subnational bonds—counter moral hazard from anticipated rescues, with evidence indicating that federations with strong no-bailout rules exhibit lower subnational deficits during downturns. However, political bargaining in transfer negotiations can lead to procyclical spending or favoritism, underscoring the need for transparent, rules-based systems to preserve fiscal discipline across levels.[94][95]Amendment and Dispute Resolution Processes

In federal systems, constitutional amendment procedures are engineered to demand concurrence across governmental tiers, preventing the central authority from unilaterally reshaping the federal compact and thereby preserving subnational autonomy. This often involves a bifurcated process: proposal at the federal level via supermajorities in legislative bodies or conventions, followed by ratification requiring explicit approval from a qualified portion of constituent units, such as states or provinces. Such rigidity contrasts with unitary systems, where amendments may hinge solely on national legislatures, and serves to embed causal safeguards against centralizing tendencies observed in historical consolidations like those under Jacobin France. Empirical analysis of over 20 federal constitutions reveals that provisions affecting the division of powers invariably incorporate subnational veto or supermajority thresholds, with only 15% allowing simple federal majorities for structural changes.[96] [97] Prominent examples illustrate this dual consent model. In the United States, Article V mandates proposal by two-thirds votes in both congressional houses or a state-called convention, with ratification by legislatures or conventions in three-fourths of states, a threshold ratified in practice for all 27 amendments since 1789.[98] In Canada, the 1982 Constitution Act's general formula (section 38) requires federal parliamentary approval plus assent from seven provinces encompassing at least half the population, while unanimity applies to alterations impacting provincial boundaries or representation. Germany's Basic Law (Article 79) similarly demands two-thirds majorities in the Bundestag and Bundesrat—the latter embodying Länder interests—for amendments impinging on federal principles like equality among units. These mechanisms have empirically constrained amendments: the U.S. Constitution has seen just 27 in 235 years, versus hundreds in more flexible unitary counterparts like France.[99] Dispute resolution between federal and subnational entities predominantly centers on judicial mechanisms, with constitutional or supreme courts functioning as neutral arbiters to interpret and enforce divisions of authority, averting escalatory conflicts through binding precedents grounded in textual and structural analysis. In most federations, these courts exercise original or appellate jurisdiction over intergovernmental claims, prioritizing enumerated powers and implied limits to maintain equilibrium; for instance, doctrines like U.S. intergovernmental tax immunity or Canadian paramountcy resolve overlaps by subordinating conflicting laws without expanding central scope absent clear constitutional warrant. Comparative studies across eight federal nations (e.g., U.S., Canada, Australia, Germany) confirm judiciaries resolve 70-80% of formal jurisdictional disputes, with outcomes favoring decentralization in cases lacking explicit federal overrides, though critics note potential for interpretive bias toward national uniformity in court compositions dominated by federal appointees.[100] [101] Supplementary political avenues complement adjudication, including intergovernmental councils, mediation committees, or executive conferences that facilitate negotiation and avert litigation, particularly for fiscal or policy coordinations lacking clear constitutional breaches. Australia's former Council of Australian Governments exemplified this by forging non-binding accords on shared issues like health funding, reducing court referrals by 40% in the 2000s per empirical tracking, while Germany's Mediation Committee reconciles Bundesrat-Bundestag deadlocks on legislation affecting states. In contexts of ethnic diversity, such as India's Inter-State Council (Article 263), these forums mitigate tensions via consensus, though their efficacy hinges on voluntary compliance absent judicial enforcement, as evidenced by persistent fiscal disputes in Brazil despite council interventions. Where political processes falter, electoral accountability—via state or federal votes—serves as a backstop, aligning resolutions with voter-derived mandates rather than insulated judicial fiat.[102] [103]Variations Across Systems

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Federalism

Symmetric federalism refers to a system in which all subnational units, such as states or provinces, possess identical constitutional powers, fiscal authorities, and representational rights within federal institutions.[104] This uniformity ensures equal treatment, facilitating consistent application of federal laws and reducing inter-unit competition for privileges.[105] In practice, symmetric systems often emerge in nations with relatively homogeneous populations or where historical integration emphasized equality among units, as seen in the original design of the U.S. Constitution, where the 13 states ratified equal powers under Article IV's full faith and credit clause.[104] Asymmetric federalism, by contrast, grants varying degrees of autonomy to subnational units based on factors like ethnic composition, historical precedents, or resource endowments, allowing tailored governance arrangements.[106] This approach recognizes diversity but introduces differential representation or veto powers, such as Quebec's distinct status in Canada under the 1982 Constitution Act, which includes unique linguistic protections and immigration authority not extended to other provinces.[107] India's system exemplifies asymmetry, with special provisions for states like Jammu and Kashmir (prior to 2019) under Article 370, granting legislative independence in residual matters until its revocation on August 5, 2019.[108] Similarly, Spain's 1978 Constitution devolves powers variably, with the Basque Country and Navarre retaining foral fiscal regimes dating to medieval pacts, collecting 100% of certain taxes locally as of 2023 data.[109]| Aspect | Symmetric Federalism | Asymmetric Federalism |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Equality among units; uniform powers promote legal consistency and national cohesion.[105] | Differentiation based on needs; equity over strict equality to address heterogeneity.[106] |

| Examples | United States (50 states with equal Senate representation); Germany (16 Länder with symmetric legislative roles post-1949 Basic Law).[104][110] | Canada (Quebec's opting-out clauses); Russia (republics with ethnic-based treaties granting resource control).[107][111] |

| Advantages | Minimizes fiscal spillovers and envy-driven demands; empirical data from U.S. states show symmetric resource allocation correlating with lower inter-state litigation rates (e.g., 15% fewer Supreme Court federalism cases per capita vs. asymmetric peers, 1789-2020).[112][104] | Enhances stability in diverse polities; Canada's asymmetry post-Meech Lake Accord (1990 failure) reduced Quebec separatism support from 60% in 1995 referendum to under 40% by 2022 polls.[106] |

| Disadvantages | Risks one-size-fits-all policies ignoring local variances, potentially fueling regional discontent as in Australia's uniform drought aid critiques during 2000s federations.[4] | Breeds inequality and coordination costs; Spain's asymmetric financing led to Basque per-capita transfers 25% above average (2010-2020), prompting Catalan fiscal grievances and 2017 independence push.[109][106] |

Comparisons with Confederalism and Unitarianism

Federalism divides sovereignty constitutionally between a central government and constituent units, granting each independent authority in designated spheres, unlike confederalism where sovereign states voluntarily delegate limited powers to a weak central body without relinquishing ultimate sovereignty, and unitarianism where subnational entities derive all powers from a supreme central authority that can unilaterally alter their status.[114] In federal systems, the central government enforces laws directly over citizens and maintains coercive powers like taxation and military, as enshrined in documents like the U.S. Constitution of 1787, whereas confederal arrangements, such as the U.S. Articles of Confederation from 1777 to 1789, relied on state compliance for implementation, leading to enforcement failures.[115] Unitary systems, exemplified by France's 1958 Constitution, centralize legislative supremacy, allowing the national parliament to override regional assemblies without constitutional barriers.[116]| Aspect | Federalism | Confederalism | Unitarianism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sovereignty | Dual: shared constitutionally between center and units | Primary: retained by states, central is agent | Central: exclusive, units subordinate |

| Power Allocation | Fixed by constitution, mutual consent for changes | Delegated voluntarily by states, revocable | Centralized, devolved at center's discretion |

| Enforcement | Direct by central over citizens | Indirect, via state cooperation | Direct by central hierarchy |

| Stability | Balances autonomy and unity, reduces secession risks through entrenched rights | Prone to dissolution due to weak center, e.g., Confederate States of America (1861-1865) | Efficient uniformity but vulnerable to overload in diverse societies |