Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fun Home

View on Wikipedia

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is a 2006 graphic memoir by the American cartoonist Alison Bechdel, author of the comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. It chronicles the author's childhood and youth in rural Pennsylvania, United States, focusing on her complex relationship with her father. The book addresses themes of sexual orientation, gender roles, suicide, emotional abuse, dysfunctional family life, and the role of literature in understanding oneself and one's family.

Key Information

Writing and illustrating Fun Home took seven years, in part because of Bechdel's laborious artistic process, which includes photographing herself in poses for each human figure.[1][2][3][4] Fun Home has been the subject of numerous academic publications in areas such as biography studies and cultural studies as part of a larger turn towards serious academic investment in the study of comics/sequential art.[5]

Fun Home has been both a popular and critical success, and spent two weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list.[6][7] In The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Sean Wilsey called it "a pioneering work, pushing two genres (comics and memoir) in multiple new directions."[8] Several publications named Fun Home as one of the best books of 2006; it was also included in several lists of the best books of the 2000s.[9] It was nominated for several awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award and three Eisner Awards (winning the Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work).[9][10] A French translation of Fun Home was serialized in the newspaper Libération; the book was an official selection of the Angoulême International Comics Festival and has been the subject of an academic conference in France.[11][12][13] Fun Home also generated controversy, being challenged and removed from libraries due to its contents.[14][15][16][17]

In 2013, a musical adaptation of Fun Home at The Public Theater enjoyed multiple extensions to its run,[18][19] with book and lyrics written by Obie Award-winning playwright Lisa Kron, and score composed by Tony Award-nominated Jeanine Tesori. The production, directed by Sam Gold, was called "the first mainstream musical about a young lesbian."[20] As a musical theatre piece, Fun Home was a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, while winning the Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Musical, the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Musical, and the Obie Award for Musical Theater.[21][22][23][24] The Broadway production opened in April 2015[25] and earned twelve nominations at the 69th Tony Awards, winning the Tony Award for Best Musical.

Background

[edit]Bechdel states that her motivation for writing Fun Home was to reflect on why things turned out the way they did in her life. She reflects on her father's untimely death and whether Alison would have made different choices if she were in his position.[26] This motivation is present throughout as she contrasts Bruce's artifice in hiding things with Alison's free and open self. The process of writing Fun Home required many references to literary works and archives to both accurately write and draw the scenes. As Bechdel wrote the book, she would reread the sources of her literary references, and this attention to detail in her references led to the development of each chapter having a different literary focus.[27] On the process of writing the book, Bechdel says, "It was such a huge project: six or seven years of drawing and excavating. It was sort of like living in a trance."[28]

Fun Home is drawn in black line art with a gray-blue ink wash.[2] Sean Wilsey wrote that Fun Home's panels "combine the detail and technical proficiency of R. Crumb with a seriousness, emotional complexity and innovation completely its own."[8] Writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, Diane Ellen Hamer contrasted "Bechdel's habit of drawing her characters very simply and yet distinctly" with "the attention to detail that she devotes to the background, those TV shows and posters on the wall, not to mention the intricacies of the funeral home as a recurring backdrop."[29] Bechdel told an interviewer for The Comics Journal that the richness of each panel of Fun Home was very deliberate:

It's very important for me that people be able to read the images in the same kind of gradually unfolding way as they're reading the text. I don't like pictures that don't have information in them. I want pictures that you have to read, that you have to decode, that take time, that you can get lost in. Otherwise what's the point?[30]

Bechdel wrote and illustrated Fun Home over a seven-year period.[1] Her meticulous artistic process made the task of illustration slow. She began each page by creating a framework in Adobe Illustrator, on which she placed the text and drew rough figures.[2][3] She used extensive photo reference and, for many panels, posed for each human figure herself, using a digital camera to record her poses.[2][3][4][31] Bechdel also used photo reference for background elements. For example, to illustrate a panel depicting fireworks seen from a Greenwich Village rooftop on July 4, 1976, she used Google Images to find a photograph of the New York skyline taken from that particular building in that period.[3][32][33] She also painstakingly copied by hand many family photographs, letters, local maps and excerpts from her own childhood journal, incorporating these images into her narrative.[32] After using the reference material to draw a tight framework for the page, Bechdel copied the line art illustration onto plate finish Bristol board for the final inked page, which she then scanned into her computer.[2][3] The gray-blue ink wash for each page was drawn on a separate page of watercolor paper, and combined with the inked image using Photoshop.[2][3][31] Bechdel chose the bluish wash color for its flexibility, and because it had "a bleak, elegiac quality" which suited the subject matter.[34] Bechdel attributes this detailed creative process to her "barely controlled obsessive-compulsive disorder".[32][35]

Plot summary

[edit]

Bruce (left) and Alison Bechdel (right).

The narrative of Fun Home is non-linear and recursive.[36] Incidents are told and re-told in the light of new information or themes.[37] Bechdel describes the structure of Fun Home as a labyrinth, "going over the same material, but starting from the outside and spiraling in to the center of the story."[38] In an essay on memoirs and truth in the academic journal PMLA, Nancy K. Miller explains that as Bechdel revisits scenes and themes "she re-creates memories in which the force of attachment generates the structure of the memoir itself."[39] Additionally, the memoir derives its structure from allusions to various works of literature, Greek myth and visual arts; the events of Bechdel's family life during her childhood and adolescence are presented through this allusive lens.[36] Miller notes that the narratives of the referenced literary texts "provide clues, both true and false, to the mysteries of family relations."[39]

The memoir focuses on Bechdel's family, and is centered on her relationship with her father, Bruce. Bruce was a funeral director and high school English teacher in Beech Creek, where Alison and her siblings grew up. The book's title comes from the family nickname for the funeral home, the family business in which Bruce grew up and later worked; the phrase also refers ironically to Bruce's tyrannical domestic rule.[40] Bruce's two occupations are reflected in Fun Home's focus on death and literature.[41]

In the beginning of the book, the memoir exhibits Bruce's obsession with restoring the family's Victorian home.[41] His obsessive need to restore the house is connected to his emotional distance from his family, which he expressed in coldness and occasional bouts of abusive rage.[41][42] This emotional distance, in turn, is connected with his being a closeted homosexual.[29] Bruce had homosexual relationships in the military and with his high school students; some of those students were also family friends and babysitters.[43] At the age of 44, two weeks after his wife requested a divorce, he stepped into the path of an oncoming Sunbeam Bread truck and was killed.[44] Although the evidence is equivocal, Alison concludes that her father died by suicide.[41][45][31]

The story also deals with Alison's own struggle with her sexual identity, reaching a catharsis in the realization that she is a lesbian and her coming out to her parents.[41][46] The memoir frankly examines her sexual development, including transcripts from her childhood diary, anecdotes about masturbation, and tales of her first sexual experiences with her girlfriend, Joan.[47] In addition to their common homosexuality, Alison and Bruce share obsessive-compulsive tendencies and artistic leanings, albeit with opposing aesthetic senses: "I was Spartan to my father's Athenian. Modern to his Victorian. Butch to his nelly. Utilitarian to his aesthete."[48] This opposition was a source of tension in their relationship, as both tried to express their dissatisfaction with their given gender roles: "Not only were we inverts, we were inversions of each other. While I was trying to compensate for something unmanly in him, he was attempting to express something feminine through me. It was a war of cross-purposes, and so doomed to perpetual escalation."[49] However, shortly before Bruce's death, he and his daughter have a conversation in which Bruce confesses some of his sexual history; this is presented as a partial resolution to the conflict between father and daughter.[50]

At several points in the book, Bechdel questions whether her decision to come out as a lesbian was one of the triggers for her father's suicide.[39][51] This question is never answered definitively, but Bechdel closely examines the connection between her father's closeted sexuality and her own open lesbianism, revealing her debt to her father in both positive and negative lights.[39][41][31]

Themes

[edit]Bechdel describes her journey of discovering her own sexuality: "My realization at nineteen that I was a lesbian came about in a manner consistent with my bookish upbringing."[52] Yet, hints of her sexual orientation arose early in her childhood; she wished "for the right to exchange [her] tank suit for a pair of shorts" in Cannes[53] and for her brothers to call her Albert instead of Alison on one camping trip.[54] Her father also exhibited homosexual behaviors, but the revelation of this made Bechdel feel uneasy. "I'd been upstaged, demoted from protagonist in my own drama to comic relief in my parents' tragedy".[55] Father and daughter handled their issues differently. Bechdel chose to accept the fact, before she had a lesbian relationship, but her father hid his sexuality.[56] He was afraid of coming out, as illustrated by "the fear in his eyes" when the conversation topic comes dangerously close to homosexuality.[57]

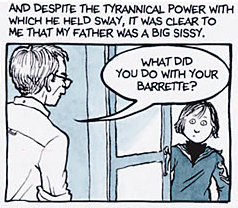

In addition to sexual orientation, the memoir touches on the theme of gender identity. Bechdel had viewed her father as "a big sissy"[58] while her father constantly tried to change his daughter into a more feminine person throughout her childhood.

The underlying theme of death is also portrayed. Unlike most young people, the Bechdel children have a tangible relationship with death because of the family mortuary business. Alison ponders whether her father's death was an accident or suicide, and finds it more likely that he killed himself purposefully.[59]

Allusions

[edit]The allusive literary references used in Fun Home are not merely structural or stylistic: Bechdel writes, "I employ these allusions ... not only as descriptive devices, but because my parents are most real to me in fictional terms. And perhaps my cool aesthetic distance itself does more to convey the Arctic climate of our family than any particular literary comparison."[60] Bechdel, as the narrator, considers her relationship to her father through the myth of Daedalus and Icarus.[61] As a child, she confused her family and their Gothic Revival home with the Addams Family seen in the cartoons of Charles Addams.[62] Bruce Bechdel's suicide is discussed with reference to Albert Camus' novel A Happy Death and essay The Myth of Sisyphus.[63] His careful construction of an aesthetic and intellectual world is compared to The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the narrator suggests that Bruce Bechdel modeled elements of his life after Fitzgerald's, as portrayed in the biography The Far Side of Paradise.[64] His wife Helen is compared with the protagonists of the Henry James novels Washington Square and The Portrait of a Lady.[65] Helen Bechdel was an amateur actress, and plays in which she acted are also used to illuminate aspects of her marriage. She met Bruce Bechdel when the two were appearing in a college production of The Taming of the Shrew, and Alison Bechdel intimates that this was "a harbinger of my parents' later marriage".[66] Helen Bechdel's role as Lady Bracknell in a local production of The Importance of Being Earnest is shown in some detail; Bruce Bechdel is compared with Oscar Wilde.[67] His homosexuality is also examined with allusion to Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time.[68] The father and daughter's artistic and obsessive-compulsive tendencies are discussed with reference to E. H. Shepard's illustrations for The Wind in the Willows.[69] Bruce and Alison Bechdel exchange hints about their sexualities by exchanging memoirs: the father gives the daughter Earthly Paradise, an autobiographical collection of the writings of Colette; shortly afterwards, in what Alison Bechdel describes as "an eloquent unconscious gesture", she leaves a library copy of Kate Millett's memoir Flying for him.[70] Finally, returning to the Daedalus myth, Alison Bechdel casts herself as Stephen Dedalus and her father as Leopold Bloom in James Joyce's Ulysses, with parallel references to the myth of Telemachus and Odysseus.[71]

The chapter headings, too, are all literary allusions.[72] The first chapter, "Old Father, Old Artificer", refers to a line in Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and the second, "A Happy Death", invokes the Camus novel. "That Old Catastrophe" is a line from Wallace Stevens's "Sunday Morning", and "In the Shadow of the Young Girls in Flower" is the literal translation of the title of one of the volumes of Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time, which is usually given in English as Within a Budding Grove.

In addition to the literary allusions which are explicitly acknowledged in the text, Bechdel incorporates visual allusions to television programs and other items of pop culture into her artwork, often as images on a television in the background of a panel.[29] These visual references include the film It's a Wonderful Life, Bert and Ernie of Sesame Street, the Smiley Face, Yogi Bear, Batman, the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, the resignation of Richard Nixon and The Flying Nun.[29][73]

Analysis

[edit]Heike Bauer, a professor at the University of London, categorizes Fun Home as part of the queer transnational archive for its contribution towards the "felt experiences" of the LGBTQ community.[26] Bauer argues that books provide a relatable source, or a felt experience, as Alison uses literature to understand her own feelings in a homophobic society.[26] Bauer notes that as Alison finds relatable literature for her experiences, Fun Home itself becomes a similar outlet for its readers by increasing representation of LGBTQ literature.[26]

Valerie Rohy, an English professor at the University of Vermont, questions the authenticity of Alison's archives in the book.[74] Rohy explores how Alison uses her diary in her childhood and readings in her young adulthood to both document her life and learn about herself through written works. On the uncertainty relating to Bruce's cause of death, Rohy says Alison concludes it to be a suicide to fill in her knowledge gap of the situation, similar to her use of books to fill in gaps in her own understanding of her childhood.[74]

Judith Kegan Gardiner, a professor of English and Gender and Women's Studies at the University of Illinois, Chicago, views Fun Home as queer literature that bends the literary norms of the graphic novel genre,[75] arguing Bechdel combines both tragedy, normally associated with men, and humor, normally associated with women, by discussing her father's death using a comic book style and dark humor. Gardiner argues Bechdel takes control of creating an open culture for lesbian feminist work through Fun Home by focusing less on Bruce's wrongdoings regarding minors, and more on the tragedy faced by Alison and the guilt towards his subsequent death after her coming out. She also says that by breaking the gender norms of the genre, particularly within lesbian and gay literature, Fun Home has dramatically affected representation.

Publication and reception

[edit]Fun Home was first printed in hardcover by Houghton Mifflin (Boston, New York City) on June 8, 2006.[76] This edition appeared on the New York Times' Hardcover Nonfiction bestseller list for two weeks, covering the period from June 18 to July 1, 2006.[6][7] It continued to sell well, and by February 2007 there were 55,000 copies in print.[77] A trade paperback edition was published in the United Kingdom by Random House under the Jonathan Cape imprint on September 14, 2006; Houghton Mifflin published a paperback edition under the Mariner Books imprint on June 5, 2007.[76][78]

In the summer of 2006, a French translation of Fun Home was serialized in the Paris newspaper Libération (which had previously serialized Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi).[11] This translation, by Corinne Julve and Lili Sztajn, was subsequently published by Éditions Denoël on October 26, 2006.[79] In January 2007, Fun Home was an official selection of the Angoulême International Comics Festival.[12] In the same month, the Anglophone Studies department of the Université François Rabelais, Tours sponsored an academic conference on Bechdel's work, with presentations in Paris and Tours.[13] At this conference, papers were presented examining Fun Home from several perspectives: as containing "trajectories" filled with paradoxical tension; as a text interacting with images as a paratext; and as a search for meaning using drag as a metaphor.[80][81][82] These papers and others on Bechdel and her work were later published in the peer-reviewed journal GRAAT (Groupe de Recherches Anglo-Américaines de Tours, or Tours Anglo-American Research Group).[83][84]

An Italian translation was published by Rizzoli in January 2007.[85][86] In Brazil, Conrad Editora published a Portuguese translation in 2007.[87] A German translation was published by Kiepenheuer & Witsch in January 2008.[88] The book has also been translated into Hungarian, Korean, and Polish,[89] and a Chinese translation has been scheduled for publication.[90]

In Spring 2012, Bechdel and literary scholar Hillary Chute co-taught a course at the University of Chicago titled "Lines of Transmission: Comics and Autobiography".[91]

Reviews and awards

[edit]The Times of London described Fun Home as "a profound and important book;" Salon.com called it "a beautiful, assured piece of work;" and The New York Times ran two separate reviews and a feature on the memoir.[8][41][92][93][94] In one New York Times review, Sean Wilsey called Fun Home "a pioneering work, pushing two genres (comics and memoir) in multiple new directions" and "a comic book for lovers of words".[8] Jill Soloway, writing in the Los Angeles Times, praised the work overall but commented that Bechdel's reference-heavy prose is at times "a little opaque".[95] Similarly, a reviewer in The Tyee felt that "the narrator's insistence on linking her story to those of various Greek myths, American novels and classic plays" was "forced" and "heavy-handed".[33] By contrast, the Seattle Times' reviewer wrote positively of the book's use of literary reference, calling it "staggeringly literate".[96] The Village Voice said that Fun Home "shows how powerfully—and economically—the medium can portray autobiographical narrative. With two-part visual and verbal narration that isn't simply synchronous, comics presents a distinctive narrative idiom in which a wealth of information may be expressed in a highly condensed fashion."[36]

Several publications listed Fun Home as one of the best books of 2006, including The New York Times, Amazon.com, The Times of London, New York magazine and Publishers Weekly, which ranked it as the best comic book of 2006.[97][98][99][100][101][102] Salon.com named Fun Home the best nonfiction debut of 2006, admitting that they were fudging the definition of "debut" and saying, "Fun Home shimmers with regret, compassion, annoyance, frustration, pity and love—usually all at the same time and never without a pervasive, deeply literary irony about the near-impossible task of staying true to yourself, and to the people who made you who you are."[103] Entertainment Weekly called it the best nonfiction book of the year, and Time named Fun Home the best book of 2006, describing it as "the unlikeliest literary success of 2006" and "a masterpiece about two people who live in the same house but different worlds, and their mysterious debts to each other."[104][105]

Fun Home was a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Award, in the memoir/autobiography category.[106][107] In 2007, Fun Home won the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Comic Book, the Stonewall Book Award for non-fiction, the Publishing Triangle-Judy Grahn Nonfiction Award, and the Lambda Literary Award in the "Lesbian Memoir and Biography" category.[108][109][110][111] Fun Home was nominated for the 2007 Eisner Awards in two categories, Best Reality-Based Work and Best Graphic Album, and Bechdel was nominated as Best Writer/Artist.[112] Fun Home won the Eisner for Best Reality-Based Work.[10] In 2008, Entertainment Weekly placed Fun Home at No. 68 in its list of "New Classics" (defined as "the 100 best books from 1983 to 2008").[113] The Guardian included Fun Home in its series "1000 novels everyone must read", noting its "beautifully rendered" details.[114]

In 2009, Fun Home was listed as one of the best books of the previous decade by The Times of London, Entertainment Weekly and Salon.com, and as one of the best comic books of the decade by The Onion's A.V. Club.[9][115]

In 2010, the Los Angeles Times literary blog "Jacket Copy" named Fun Home as one of "20 classic works of gay literature".[116] In 2019, the graphic novel was ranked 33rd on The Guardian's list of the 100 best books of the 21st century.[117] In 2024, The New York Times ranked it #35 of the 100 best books of the 21st century.[118]

Challenges and attempted banning

[edit]2006: Marshall, Missouri

[edit]In October 2006, a resident of Marshall, Missouri, attempted to have Fun Home and Craig Thompson's Blankets, both graphic novels, removed from the city's public library.[119] Supporters of the books' removal characterized them as "pornography" and expressed concern that they would be read by children.[14][120] Marshall Public Library Director Amy Crump defended the books as having been well-reviewed in "reputable, professional book review journals", and characterized the removal attempt as a step towards "the slippery slope of censorship".[119][120] On October 11, 2006, the library's board appointed a committee to create a materials selection policy, and removed Fun Home and Blankets from circulation until the new policy was approved.[121][122] The committee "decided not to assign a prejudicial label or segregate [the books] by a prejudicial system", and presented a materials selection policy to the board.[123][124] On March 14, 2007, the Marshall Public Library Board of Trustees voted to return both Fun Home and Blankets to the library's shelves.[15] Bechdel described the attempted banning as "a great honor", and described the incident as "part of the whole evolution of the graphic-novel form."[125]

2008: University of Utah

[edit]In 2008, an instructor at the University of Utah placed Fun Home on the syllabus of a mid-level English course, "Critical Introduction to English Literary Forms".[126] One student objected to the assignment, and was given an alternate reading in accordance with the university's religious accommodation policy.[126] The student subsequently contacted a local organization called "No More Pornography", which started an online petition calling for the book to be removed from the syllabus.[16] Vincent Pecora, the chair of the university's English department, defended Fun Home and the instructor.[16] The university said that it had no plans to remove the book.[16]

2013: Palmetto Family

[edit]In 2013, Palmetto Family Council, a conservative South Carolina group affiliated with Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council, challenged the inclusion of Fun Home as a reading selection for incoming freshmen at the College of Charleston.[17][127][128] Palmetto Family president Oran Smith called the book "pornographic".[127] Bechdel disputed this, saying that pornography is designed to cause sexual arousal, which is not the purpose of her book.[17] The controversy made its way to the Senate and House of Representatives. In the Senate they were voting on whether or not to make budget cuts to the summer reading program for incoming freshmen. Senator Brad Hutto used a four-hour filibuster to delay the voting process and felt that this was "a challenge to academic freedom and an act that would shame our state."[129] There was an alternative for students who find that the selection of reading chosen by their institution is offensive: they are offered a College Reads! as the alternative. The past president of College of Charleston, Glenn McConnell, had contradicting opinions on Fun Home. When asked about the reading he stated that professors have academic freedom when it comes to what they teach in the classroom, but they should also ask themselves if it is worth it and "it certainly wouldn't be my book of choice."[129] The punishment given to the college was a cut to funding to prevent the institution from exploring identity and sexuality. Many tried to fight this because it was seen as a restriction and became a "battlefield in a full-blown culture war."[130]

College provost George Hynd and associate provost Lynne Ford defended the choice of Fun Home, pointing out that its themes of identity are especially appropriate for college freshmen.[17] However, seven months later, the Republican-led South Carolina House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee cut the college's funding by $52,000, the cost of the summer reading program, to punish the college for selecting Fun Home.[131][132] Rep. Garry Smith, who proposed the cuts, said that in choosing Fun Home the university was "promoting the gay and lesbian lifestyle".[132][133] Rep. Stephen Goldfinch, another supporter of the cuts, said, "This book trampled on freedom of conservatives. ... Teaching with this book, and the pictures, goes too far."[134] Bechdel called the funding cut "sad and absurd" and pointed out that Fun Home "is after all about the toll that this sort of small-mindedness takes on people's lives."[135] The full state House of Representatives subsequently voted to retain the cuts.[136] College of Charleston students and faculty reacted with dismay and protests to the proposed cuts, and the college's Student Government Association unanimously passed a resolution urging that the funding be restored.[137][138][139] A coalition of ten free-speech organizations wrote a letter to the South Carolina Senate Finance Committee, urging them to restore the funds and warning them that "[p]enalising state educational institutions financially simply because members of the legislature disapprove of specific elements of the educational program is educationally unsound and constitutionally suspect".[138][140][141] The letter was co-signed by the National Coalition Against Censorship, the ACLU of South Carolina, the American Association of University Professors, the Modern Language Association, the Association of College and Research Libraries, the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, the Association of American Publishers, the National Council of Teachers of English and the American Library Association.[141][142] After a nearly week-long debate in which Fun Home and Bechdel were compared to slavery, Charles Manson and Adolf Hitler, the state Senate voted to restore the funding, but redirect the funds towards study of the United States Constitution and The Federalist Papers; the university was also required to provide alternate books to students who object to an assignment due to a "religious, moral or cultural belief".[143][144][145] Governor Nikki Haley approved the budget measure penalizing the university.[146]

2015: Duke University

[edit]In 2015, the book was assigned as summer reading for the incoming class of 2019 at Duke University. Several students objected to the book on moral and/or religious grounds.[147]

2018: Somerset County, New Jersey

[edit]In 2018, parents challenged Fun Home in the Watchung Hills Regional High School curriculum. The challenge was rejected, and the book remained in the school. One year later, a lawsuit was filed in May 2019 against the administrators of the school asking for removal of the book. The lawsuit claims that if the book is not removed, "minors will suffer irreparable harm and that New Jersey statutes will be violated."[148] After the Watchung Hills High School challenge, administrators at nearby North Hunterdon High School removed Fun Home from their libraries as well, but the book was later restored in February 2019.[149]

2022: Wentzville, Missouri

[edit]In January 2022, the Wentzille school board in Missouri voted 4–3 to ban Fun Home, going against the review committee's 8–1 vote to retain the book in the district's libraries.[150] The ban included three other books, as well: George M. Johnson's All Boys Aren't Blue, Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye, and Kiese Laymon's Heavy.[150]

2022: Rapid City, South Dakota

[edit]In May 2022, parents challenged Fun Home in the Rapid City Area Schools, claiming the book is "pornographic" and the overall picture of having books similar to Fun Home in schools is a "Marxist Revolution." Some teachers disagreed because the book represents the highly marginalized voices of the LGBTQ+ community. The school board decided to temporarily remove the book.[151]

2023: Sheboygan, Wisconsin

[edit]In January 2023, Sheboygan South High School principal, Kevin Formolo, removed Fun Home from the school's library after community members expressed outrage about the book's inclusion. Supporters of the principal's decision say the sexual content of the book is inappropriate in a school setting. Others equated the removal of the book from the school's library to discrimination.

Two other books were also removed from the library by the principal, Alison Bechdel's Are You My Mother? and Maia Kobabe's Gender Queer.[152]

2025: Alberta, Canada

[edit]In July 2025, the conservative provincial government of Alberta, led by Premier Danielle Smith, issued an order to school libraries restricting books with "explicit sexual content".[153] Alberta’s Education and Childcare Minister Demetrios Nicolaides did not provide a list of books to be removed, but provided four examples of sexually explicit content: Fun Home by Bechdel, Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe; Blankets by Craig Thompson; and Flamer by Mike Curato. Notably, all four examples of objectionable materials are graphic novels depicting coming-of-age and LGBTQ subjects.[154]

In August of 2025, the Edmonton Public School Board's internally distributed a list of over 200 books to be removed from library shelves in order to comply with the new policy.[155] The list included literary classics including The Handmaid's Tale, Brave New World, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. When the list was leaked to the public, major backlash[156][157][158] ensued forcing the government to pause implementation[159] .

In September 2025, the government announced a revised policy that requires removal of only visual representations deemed sexually explicit.[160] The examples of objectionable materials continue to include Bechdel's Fun Home.

Adaptations

[edit]Stage musical

[edit]Fun Home has been adapted into a stage musical, with a book by Lisa Kron and music by Jeanine Tesori. The musical was developed through a 2009 workshop at the Ojai Playwrights Conference and workshopped in 2012 at the Sundance Theatre Lab and The Public Theater's Public Lab.[161][162][163] Bechdel did not participate in the musical's creation. She expected her story to seem artificial and distant on stage, but she came to feel that the musical had the opposite effect, bringing the "emotional heart" of the story closer than even her book did.[164]

The musical debuted Off-Broadway at The Public Theater on September 30, 2013.[18] The production was directed by Sam Gold and starred Michael Cerveris and Judy Kuhn as Bruce and Helen Bechdel. The role of Alison was played by three actors: Beth Malone played the adult Alison, reviewing and narrating her life, Alexandra Socha played "Medium Alison" as a student at Oberlin, discovering her sexuality, and Sydney Lucas played Small Alison, at age 10. It received largely positive reviews,[165][166][167] and its limited run was extended several times until January 12, 2014.[19] The musical was a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Drama; it also won the Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Musical, the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Musical, and the Obie Award for Musical Theater.[21][22][23][24] Alison Bechdel drew a one-page comic about the musical adaptation for the newspaper Seven Days.[168]

A Broadway production opened at Circle in the Square Theatre in April 2015. The production won five 2015 Tony Awards, including Best Musical,[169] and ran for 26 previews and 582 regular performances until September 10, 2016, with a national tour that began in October 2016.[170] Kalle Oskari Mattila, in The Atlantic, argued that the musical's marketing campaign "obfuscates rather than clarifies" the queer narrative of the original novel.[171]

Potential musical film

[edit]In January 2020, Jake Gyllenhaal and a partner secured the rights to produce a film version of the musical, planning to star Gyllenhaal as Bruce Bechdel with Sam Gold directing and Amazon MGM Studios distributing.[172] In 2023, according to Alison Bechdel, she will not have direct involvement on the project and Gyllenhaal was no longer involved in any upcoming film adaptation. She did, however, say "They're still trying to make this movie happen, but it will have a different star."[173] However, on April 2, 2024, Gyllenhaal was confirmed to remain involved on the film as a producer when he and his Nine Stories Productions banner signed a first-look deal with Amazon MGM.[174]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Emmert, Lynn (April 2007). "Life Drawing". The Comics Journal (282). Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books: 36. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Emmert, Lynn (April 2007). "Life Drawing". The Comics Journal (282). Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books: 44–48. Print edition only.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison, Margot (May 31, 2006). "Life Drawing". Seven Days. Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Bechdel, Alison (April 18, 2006). "OCD" (video). YouTube. Archived from the original on December 19, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ e.g. Tolmie, Jane (2009). "Modernism, Memory and Desire: Queer Cultural Production in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home." Topia: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies. 22: 77–96;

Watson, Julia (2008). "Autographic Disclosures and Genealogies of Desire in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home". Biography. 31 (1): 27–58. doi:10.1353/bio.0.0006. S2CID 161762349. - ^ a b "Hardcover Nonfiction" (free registration required). The New York Times. July 9, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ a b "Hardcover Nonfiction" (free registration required). The New York Times. July 16, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ a b c d Wilsey, Sean (June 18, 2006). "The Things They Buried" (free registration required). Sunday Book Review. The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ a b c Bechdel, Alison. "News and Reviews". dykestowatchoutfor.com. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ a b "The 2007 Eisner Awards: Winners List". San Diego Comic-Con website. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ a b Bechdel, Alison (July 26, 2006). "Tour de France". Blog. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b "Official 2007 Selection". Angoulême International Comics Festival. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Cherbuliez, Juliette (January 25, 2007). "There's No Place like (Fun) Home". Transatlantica. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Twiddy, David (November 14, 2006). "As more graphic novels appear in libraries, so do challenges". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ a b Harper, Rachel (March 15, 2007). "Library board approves new policy/Material selection policy created, controversial books returned to shelves". The Marshall Democrat-News. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Dallof, Sarah (March 27, 2008). "Students protesting book used in English class". KSL-TV. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Knich, Diane (July 25, 2013). "Palmetto Family conservative group concerned about College of Charleston's freshman book selection". The Post and Courier. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Gioia, Michael. "Michael Cerveris, Judy Kuhn, Alexandra Socha Among Cast of Fun Home; Other Public Theater Casting Announced, Too". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Gioia, Michael; Hetrick, Adam (December 4, 2013). "Jeanine Tesori-Lisa Kron Musical 'Fun Home' Given Fourth Extension". Playbill. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Thomas, June. "Fun Home: Is America Ready for a Musical About a Butch Lesbian?". Slate. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ a b "Drama". The Pulitzer Prizes. Columbia University. April 14, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "2014 Nominations". The Lucille Lortel Awards. May 4, 2014. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Healy, Patrick (May 5, 2014). "Critics' Circle Names 'Fun Home' Best Musical". New York Times. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Lucchesi, Nick (May 19, 2014). "Village Voice Announces Winners of 59th Annual Obie Awards, Names Tom Sellar Lead Theater Critic". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (August 7, 2014). "'Fun Home' Will Reach Broadway Just Before Tonys Deadline". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Bauer, Heike (2014). "Vital Lines Drawn From Books: Difficult Feelings in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home and Are You My Mother?" (PDF). Journal of Lesbian Studies. 18 (3): 266–281. doi:10.1080/10894160.2014.896614. PMID 24972285. S2CID 38954208.

- ^ Chute, Hillary L.; Bechdel, Alison (2006). "An Interview with Alison Bechdel". MFS Modern Fiction Studies. 52 (4): 1004–1013. doi:10.1353/mfs.2007.0003. ISSN 1080-658X. S2CID 161730250.

- ^ Cooke, Rachel (November 5, 2017). "Fun Home creator Alison Bechdel on turning a tragic childhood into a hit musical". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Hamer, Diane Ellen (May 2006). "My Father, My Self". Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 13 (3): 37. ISSN 1532-1118. Archived from the original on July 18, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ Emmert, p. 46. Print edition only.

- ^ a b c d Bechdel, Alison. "Alison Bechdel: Comic Con 2007". Velvetpark (Interview). Interviewed by Michelle Paradise. Archived from the original (Flash Video) on August 22, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c Swartz, Shauna (May 8, 2006). "Alison Bechdel's Life in the Fun Home". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Brooks, Carellin (August 23, 2006). "A Dyke to Watch Out For". The Tyee. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Emmert, pp. 47–48. Print edition only.

- ^ Emmert, p. 45. Print edition only.

- ^ a b c Chute, Hillary (July 11, 2006). "Gothic Revival". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on July 19, 2006. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ Deppey, Dirk (January 17, 2007). "12 Days". The Comics Journal (Web Extras ed.). Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison (Interviewee), Seidel, Dena (Editor) (2008). Alison Bechdel's Graphic Narrative (Web video). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Writers House. Event occurs at 04:57. Archived from the original (Flash Video) on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Nancy K. (March 2007). "The Entangled Self: Genre Bondage in the Age of the Memoir". PMLA. 122 (2): 543–544. doi:10.1632/pmla.2007.122.2.537. ISSN 0030-8129. S2CID 163034462.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison (2006). Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 36. ISBN 0-618-47794-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gustines, George Gene (June 26, 2006). "'Fun Home': A Bittersweet Tale of Father and Daughter" (free registration required). The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 11, 18, 21, 68–69, 71.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 58–59, 61, 71, 79, 94–95, 120.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 27–30, 59, 85.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 23, 27–29, 89, 116–117, 125, 232.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 58, 74–81,

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 76, 80–81, 140–143, 148–149, 153, 157–159, 162, 168–174, 180–181, 183–186, 207, 214–215, 224.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 15.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 98.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 57–59, 86, 117, 230–232.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 74.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 73.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 113

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 58.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 76–81.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 219.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 97

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 67

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 3–4, 231–232.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 27–28, 47–49.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 61–66, 84–86.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 66–67, 70–71.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 154–155, 157–158, 163–168, 175, 180, 186.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 92–97, 102, 105, 108–109, 113, 119–120.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 130–131, 146–147, 150.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 205, 207–208, 217–220, 224, 229.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 201–216, 221–223, 226, 228–231.

- ^ Chute, Hillary L. (2010). Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231150637.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 10–11 (It's a Wonderful Life), 14 (Sesame Street), 15 (Smiley Face), 92 (Yogi Bear), 130 (Batman), 174–175 (Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote), 181 (Nixon), 131, 193 (The Flying Nun).

- ^ a b Rohy, Valerie (2010). "In the Queer Archive: Fun Home". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 16 (3): iv-361. doi:10.1215/10642684-2009-034. S2CID 145624992.

- ^ Judith Kegan Gardiner, Queering Genre: Alison Bechdel's Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For, Contemporary Women's Writing, Volume 5, Issue 3, November 2011, Pages 188–207, doi:10.1093/cww/vpr015

- ^ a b Bechdel, Alison (2007). "Fun Home". Houghton Mifflin website. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-87171-1. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Comics Bestsellers: February 2007". Publishers Weekly. February 6, 2007. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Book Details for Fun Home". Random House UK website. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Fun Home". Éditions Denoël website (in French). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Chabani, Karim (March 2007). "Double Trajectories: Crossing Lines in Fun Home" (PDF). GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Muller, Agnés (March 2007). "Image as Paratext in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home" (PDF). GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Tison, Hélène (March 2007). "Drag as metaphor and the quest for meaning in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic" (PDF). GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Tison, Hélène, ed. (March 2007). "Reading Alison Bechdel". GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ "Groupe de Recherches Anglo-Américaines de Tours". Université François Rabelais, Tours (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ^ "Fun Home". Rizzoli (in Italian). RCS MediaGroup. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ "Libro Fun Home". Libraria Rizzoli (in Italian). RCS MediaGroup. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ Magnani, Deborah (March 20, 2010). "Fun Home: Uma Tragicomédia Em Família". cubo3 (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Fun Home" (in German). Kiepenheuer & Witsch. January 2008. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ Abiekt.pl (October 9, 2008). "Fun Home. Tragikomiks rodzinny". abiekt.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison (August 14, 2008). "china, translated". dykestowatchoutfor.com. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ^ "Lines of Transmission: Comics and Autobiography". Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry. University of Chicago. 2012. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (June 5, 2006). "Fun Home". Salon.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2006.

- ^ Reynolds, Margaret (September 16, 2006). "Images of the fragile self". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Bellafante, Ginia (August 3, 2006). "Twenty Years Later, the Walls Still Talk" (paid archive). The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ Soloway, Jill (June 4, 2006). "Skeletons in the closet". Los Angeles Times. p. R. 12. Archived from the original (paid archive) on July 23, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- ^ Pachter, Richard (June 16, 2006). ""Fun Home": Sketches of a family circus". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ^ "100 Notable Books of the Year" (free registration required). Sunday Book Review. The New York Times. December 3, 2006. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- ^ "Best Books of 2006: Editors' Top 50". amazon.com. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ "Best of 2006 Top 10 Editors' Picks: Memoirs". amazon.com. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ Gatti, Tom (December 16, 2006). "The 10 best books of 2006: number 10 — Fun Home". The Times. London. Retrieved December 18, 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Bonanos, Christopher; Hill., Logan; Holt, Jim; et al. (December 18, 2006). "The Year in Books". New York. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- ^ "The First Annual PW Comics Week Critic's Poll". Publishers Weekly Online. Publishers Weekly. December 19, 2006. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ Miller, Laura; Hillary Frey (December 12, 2006). "Best debuts of 2006". salon.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- ^ Reese, Jennifer (December 29, 2006). "Literature of the Year". Entertainment Weekly. No. 913–914. Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ Grossman, Lev; Richard Lacayo (December 17, 2006). "10 Best Books". Time. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Getlin, Josh (January 21, 2007). "Book Critics Circle nominees declared". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original (free abstract of paid archive) on October 1, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ "NBCC Awards Finalists". National Book Critics Circle website. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ "18th Annual GLAAD Media Awards in San Francisco". Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ "Holleran, Bechdel win 2007 Stonewall Book Awards". American Library Association. January 22, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ "Alison Bechdel Among Triangle Award Winners". The Book Standard. May 8, 2007. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- ^ "Lambda Literary Awards Announce Winners". Lambda Literary Foundation. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ "The 2007 Eisner Awards: 2007 Master Nominations List". San Diego Comic-Con website. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ "The New Classics: Books". Entertainment Weekly. No. 999–1000. June 27, 2008. Archived from the original on August 31, 2008. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ Taylor, Craig (January 20, 2009). "1000 novels everyone must read: The best graphic novels". The Guardian. London. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ McIntosh, Lindsay (November 14, 2009). "The 100 Best Books of the Decade". The Times. London. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed as No. 42 of 100.

"Books: The 10 Best of the Decade". Entertainment Weekly. December 3, 2009. Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed as No. 7 of 10.

Miller, Laura (December 9, 2009). "The best books of the decade". Salon.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed chronologically in a list of 10 non-fiction works.

Handlen, Zack; Heller, Jason; Murray, Noel; et al. (November 24, 2009). "The best comics of the '00s". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed alphabetically in a list of 25. - ^ Kellogg, Carolyn; Nick, Owchar; Ulin, David L. (August 4, 2010). "20 classic works of gay literature". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "The 100 best books of the 21st century". The Guardian. September 21, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Staff, The New York Times Books (July 8, 2024). "The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 6, 2025.

- ^ a b Sims, Zach (October 3, 2006). "Library trustees to hold hearing on novels". The Marshall Democrat-News. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ^ a b Sims, Zach (October 5, 2006). "Library board hears complaints about books/Decision scheduled for Oct. 11 meeting". The Marshall Democrat-News. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ^ Brady, Matt (October 12, 2006). "Marshall Library Board Votes to Adopt Materials Selection Policy". Newsarama. Archived from the original on November 19, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2006.

- ^ Sims, Zach (October 12, 2006). "Library board votes to remove 2 books while policy for acquisitions developed". The Marshall Democrat-News. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2006.

- ^ Harper, Rachel (January 25, 2007). "Library board ready to approve new materials selection policy". The Marshall Democrat-News. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Harper, Rachel (February 8, 2007). "Library policy has first reading". The Marshall Democrat-News. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- ^ Emmert, p. 39. Retrieved on August 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Vanderhooft, JoSelle (April 7, 2008). "Anti-Porn Group Challenges Gay Graphic Novel". QSaltLake. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b "College of Charleston freshman book questioned". WCIV. Associated Press. July 26, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Bowers, Paul (July 26, 2013). "CofC freshman book ruffles conservative group's feathers". Charleston City Paper. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Piepmeier, Alison (May 12, 2014). "Flawed compromise emerges in Fun Home controversy". Charleston City Paper. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Bowers, Paul (September 26, 2018). "In Banned Books class at College of Charleston, Salman Rushdie meets Captain Underpants". Post and Courier. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Adcox, Seanna (February 19, 2014). "SC lawmakers vote to punish colleges' book choices". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Borden, Jeremy (February 20, 2014). "Palmetto Sunrise: College of Charleston dollars cut for 'promotion of lesbians'". The Post and Courier. Charleston, SC. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Driscoll, Molly (February 28, 2014). "Alison Bechdel's memoir 'Fun Home' runs into trouble with the South Carolina House of Representatives". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ Shain, Andrew (March 15, 2014). "Lawmakers to S.C. colleges: Choose freedom or funding". The State. Columbia, SC: McClatchy. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Deahl, Rachel (February 26, 2014). "Bechdel Reacts to 'Fun Home' Controversy in So. Carolina". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ Adcox, Seanna (March 10, 2014). "SC House refuses to restore college cuts for books". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ Catalano, Trevor (March 24, 2014). "Students and Faculty React to Budget Cuts Due to Unsupported Material". CisternYard Media. Charleston, SC. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Langley, Cuthbert (March 18, 2014). "ACLU enters "College Reads!" debate as State Rep. apologizes for harsh email". WCBD-TV. Charleston, SC: Media General. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Elmore, Christina (March 29, 2014). "Protesters rally against proposed book-linked budget cuts at the College of Charleston". The Post and Courier. Charleston, SC: Evening Post Industries. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ Armitage, Hugh (March 24, 2014). "South Carolina warned over "unconstitutional" Fun Home uni cuts". Digital Spy. London: Hearst Magazines UK. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Kingkade, Tyler (March 18, 2014). "These College Budget Cuts Risk Violating The First Amendment, State Lawmakers Are Warned". Huffington Post. New York. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ O'Connor, Acacia (March 18, 2014). "Letter Urges S.C. Legislature to Restore Funding to Universities with LGBT Curricula". National Coalition Against Censorship. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Borden, Jeremy (May 7, 2014). "Sen. Brad Hutto filibuster delays decision on College of Charleston 'Fun Home' budget cuts; GOP calls book pornography". The Post and Courier. Charleston, SC: Evening Post Industries. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Borden, Jeremy (May 13, 2014). "S.C. Senate votes to fund teaching U.S. Constitution as compromise on book cuts at College of Charleston". The Post and Courier. Charleston, SC: Evening Post Industries. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ McLeod, Harriet (May 13, 2014). "South Carolina Senate won't cut college budgets over gay-themed books". Business Insider. Reuters. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Thomason, Andy (June 16, 2014). "S.C. Governor Upholds Penalties for Gay-Themed Books in State Budget". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Washington, DC. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Ballentine, Claire (August 21, 2015). "Freshmen skipping 'Fun Home' for moral reasons". The Duke Chronicle. Durham, NC. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ^ "Lawsuit Demands Fun Home Removed | Comic Book Legal Defense Fund". May 15, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ "Victory! Fun Home Restored in New Jersey High Schools | Comic Book Legal Defense Fund". February 26, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Schaub, Michael (January 25, 2022). "Missouri School District Bans Toni Morrison Book". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Grossman, Hannah (May 5, 2022). "South Dakotans flame school board meeting over 'pornographic' books: 'This is the Marxist global revolution'". Fox News. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ Goldbeck, Madison (January 24, 2023). "Sheboygan school pulls 3 books from library after outrage over sexual content". WTMJ4. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ Alberta, Government of (July 10, 2025). "New standards for school libraries | De nouvelles normes pour les bibliothèques scolaires". www.alberta.ca.

- ^ Johnson, Lisa (July 10, 2025). "Alberta bans school library books it deems sexually explicit". CBC. Retrieved September 4, 2025.

- ^ Williams, Emily (August 28, 2025). "The Handmaid's Tale among more than 200 books to be pulled at Edmonton public schools | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ^ Cecco, Leyland (September 2, 2025). "Margaret Atwood releases satirical short story critiquing book bans in Canada". The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ^ Villani, Mark (August 30, 2025). "Alberta's school book removals spark backlash from educators, authors, students". CTVNews. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ^ "CCLA Sounds the Alarm Over Government of Alberta's Dangerous Censorship Agenda". Canadian Civil Liberties Association. August 29, 2025. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ^ Cecco, Leyland (September 3, 2025). "Canada: Alberta pauses book ban after schools remove Handmaid's Tale, 1984 and other classics". The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ^ French, Janet. "New Alberta school books order bans explicit images of sexual acts | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved September 10, 2025.

- ^ Hetrick, Adam (August 4, 2009). "Ojai Playwrights Conference Begins in CA; Kron and Tesori Pen New Musical". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ Boehm, Mike (July 10, 2012). "Cherry Jones, Raul Esparza give Sundance Theatre Lab star power". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ Hetrick, Adam (September 11, 2012). "Jeanine Tesori-Lisa Kron Musical Fun Home Will Debut at the Public; Judy Kuhn to Star". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison. "Alison Bechdel Draws a Fun Home Coda". Vulture. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (October 23, 2013). "Family as a Hall of Mirrors". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Dziemianowicz, Joe (October 22, 2013). ""Fun Home," theater review. Public Theater musical about a small-town family is dark but magnificent". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ McNulty, Charles (October 23, 2013). "Awkwardness adds to 'Fun Home' charm Muddled beginning, smudgy staging and distracting songs in this musical ultimately add up to a tender honesty". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison (July 2, 2014). "Fun Home! The Musical!". Seven Days. Burlington, Vermont: Da Capo Publishing. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Sims, David (June 8, 2015). "Fun Home's Success Defines the 2015 Tony Awards". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ Gordon, Jessica Fallon. "Photo Coverage: Fun Home Closes on Broadway with Emotional Final Curtain Call", BroadwayWorld.com, September 11, 2016

- ^ Mattila, Kalle Oskari. "Selling Queerness: The Curious Case of Fun Home", The Atlantic, April 25, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2017

- ^ Lefkowitz, Andy. "Jake Gyllenhaal to Produce & Star in Movie Musical Adaptation of Fun Home", Broadway.com, January 3, 2020

- ^ Lickteig, Mary Ann. "Cartoonist Alison Bechdel Headlines the Green Mountain Book Festival", Seven Days, September 27, 2023

- ^ "Jake Gyllenhaal's Nine Stories Signs First-Look Deal with Amazon MGM". The Hollywood Reporter. April 2, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Houghton Mifflin's Fun Home press release, with excerpts from the book and video of Bechdel's artistic process

- dykestowatchoutfor.com, author Alison Bechdel's blog and official website

- What the Little Old Ladies Feel: How I told my mother about my memoir. Slate article by Bechdel

Fun Home

View on GrokipediaBackground and Creation

Author and Family Context

Alison Bechdel was born on September 10, 1960, in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, to Bruce Allen Bechdel and Helen Augusta (née Fontana) Bechdel.[6] The family lived in the small town of Beech Creek, approximately ten miles away, where they managed the local funeral home, which Bechdel and her siblings nicknamed the "Fun Home." Bechdel has two younger brothers, Christian and John.[7] Her upbringing in this environment, marked by the constant presence of death and the family's Victorian house restorations, forms the backdrop for her graphic memoir Fun Home.[8] Bruce Bechdel (1936–1980) worked as a high school English teacher and part-time funeral director, continuing the third-generation family business.[9] He was an avid reader, antique collector, and president of the Clinton County Historical Society, with interests in literature and aesthetics that influenced his daughter's artistic development.[8] However, Bruce maintained a closeted homosexual life, engaging in affairs with men, including teenagers, while enforcing strict discipline at home, which strained family relations.[10] Helen Bechdel (1933–2013) taught high school English and had aspired to a career in acting, having met Bruce during a college production of The Taming of the Shrew.[11] She tolerated her husband's infidelity for decades, prioritizing family stability and her children's upbringing over personal fulfillment. On July 2, 1980, Bruce was fatally struck by a truck near the family home; while officially ruled an accident, Bechdel interprets it as suicide, citing his recent dismissal from teaching, lack of a note, and timing shortly after her coming out as a lesbian.[12]Development Process

Alison Bechdel commenced work on Fun Home in the late 1990s, devoting approximately seven years to its creation while concurrently producing her syndicated webcomic Dykes to Watch Out For every two weeks, which extended the timeline due to divided attention.[13] The project marked a departure from her episodic strip format toward a unified graphic memoir, requiring her to forge a cohesive narrative from fragmented personal recollections without an initial outline or endpoint in mind.[14] The writing process unfolded as an exploratory endeavor, beginning with textual accounts of pivotal memories that Bechdel excavated through introspection, aided by ongoing therapy to probe psychological depths and family dynamics.[13] She drew upon primary source materials including childhood diaries and family photographs, which provided raw visual and textual anchors to sequence non-linear events and highlight contrasts, such as shifts in her mother's demeanor across decades.[15] Midway through, Bechdel crafted an illustrated synopsis to pitch the unfinished work to publishers, securing a contract with Houghton Mifflin and subsequent editorial guidance to refine the structure into chapters.[13] Drawing and design integrated seamlessly with writing, involving meticulous manual labor over each page—adjusting panels to harmonize images, dialogue, captions, and allusions in a novel graphic syntax akin to carpentry, where text and visuals iteratively shaped one another.[14][16] Bechdel entered a trance-like state during this phase, balancing obsessive precision with emotional detachment to render intimate revelations, though she later described exposing her family's secrets—particularly to her reticent mother—as profoundly distressing.[17] This labor-intensive method, devoid of digital shortcuts, underscored the memoir's physicality and pushed the boundaries of comics as a medium for literary introspection.[16]Initial Publication Details

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic was first published in hardcover on June 8, 2006, by Houghton Mifflin Company in Boston and New York.[18][19] The first edition featured 232 pages of black-and-white illustrations and text, with ISBN-10 0618477942.[18][20] A paperback edition followed on June 5, 2007, from Mariner Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.[19][21]Content Overview

Plot Synopsis

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is a graphic memoir by Alison Bechdel that chronicles her childhood in Beech Creek, Pennsylvania, and her intricate relationship with her father, Bruce Bechdel, who directed the family's funeral home, locally known as the "Fun Home."[22] [23] The narrative unfolds non-linearly across seven chapters, drawing parallels between Bechdel's emerging lesbian identity and her father's concealed homosexuality, framed through literary allusions such as Homer's Odyssey and Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time.[22] [24] The story begins with a childhood anecdote of Bechdel, at age three, tumbling into her father's arms during play, evoking the myth of Daedalus and Icarus to symbolize their inverted dynamic—Bruce as the controlling craftsman imposing aesthetic order on their Victorian home and family life, while suppressing his desires.[25] Bruce, a high school English teacher and funeral director, maintained a facade of propriety, enforcing strict rules on his three children—Alison and her brothers John and Christian—despite his own clandestine affairs with young men, including family acquaintances and students.[26] [23] In 1980, shortly after Bechdel comes out as lesbian to her parents while a student at Oberlin College, Bruce dies in a truck accident on a rural highway, which Bechdel interprets as probable suicide amid his lifelong internal conflict.[24] [27] This event prompts Bechdel's mother, Helen, to reveal Bruce's history of homosexuality, infidelity, and a 1960s court case involving statutory rape charges from an encounter with a teenage handyman.[23] Bechdel reflects on intercepted letters and diaries exposing her father's double life, contrasting his emotional unavailability with fleeting moments of connection, such as shared literary discussions.[22] Bechdel's college years interlace with flashbacks, detailing her first same-sex relationship with classmate Joan and her obsessive cataloging of gay icons in literature to affirm her identity, mirroring Bruce's escapist reading habits.[24] The memoir culminates in Bechdel grappling with inherited traits—repressed desires, perfectionism, and a penchant for fabrication—while mourning her father, whose death she views as a release he denied himself through denial and performance.[26] [27]Core Themes

Fun Home centers on the complex father-daughter relationship between Alison Bechdel and her father, Bruce, highlighting parallels in their sexual orientations—his repressed homosexuality and her emerging lesbian identity—as a lens for exploring inherited queerness and emotional distance within the family. Bechdel depicts her father's closeted life as a source of domestic tension, where his aesthetic obsessions and infidelities masked inner turmoil, contrasting with her own path toward openness after coming out in college. This dynamic underscores themes of repression versus authenticity, as Bruce's inability to live openly contributed to a performative family facade, including the dual role of the family-run funeral home symbolizing death and concealment.[28][19] A pivotal theme is the interpretation of Bruce's 1980 suicide, shortly after Alison's coming-out letter, which Bechdel scrutinizes for possible causal links to guilt, liberation from secrecy, or longstanding depression tied to his orientation in a conservative era. The memoir probes grief and melancholia, with Bechdel using nonlinear reflection to process unresolved loss, questioning whether her disclosure prompted his death or merely coincided with it, while drawing on psychoanalytic concepts to unpack familial inheritance of trauma. Emotional abuse and dysfunction emerge through vignettes of Bruce's strictness and mother's complicity, revealing how parental secrets fostered Alison's hyper-vigilance and self-analysis.[29][30] Gender roles and identity formation constitute another core thread, as Bechdel contrasts her butch presentation and rejection of femininity with her father's dandyish masculinity, illustrating how both navigated societal expectations around sexuality and performance. The narrative critiques artifice in self-presentation, from Bruce's curated home restorations to Alison's diary rituals, emphasizing truth-seeking amid deception. Self-discovery intertwines with these, as Alison reconstructs her past to affirm her lesbian identity, free from her father's constraints, though haunted by his unfulfilled potential.[31][32][33]Literary and Cultural Allusions

Fun Home employs a dense array of literary allusions to parallel the Bechdel family's dynamics with canonical works, particularly framing Bruce Bechdel's closeted homosexuality and suicide through the lens of modernist literature and classical mythology.[34] Bechdel explicitly uses references to authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marcel Proust, and James Joyce not merely as ornament but to elucidate psychological and biographical parallels, as she notes these serve to "illustrate" her narrative points rather than purely as shorthand.[35] This intertextuality underscores the memoir's exploration of how fiction shapes personal truth, with Bruce's obsessions—evident in his teaching Alison about Fitzgerald and Joyce—mirroring his repressed desires.[36] Greek mythology features prominently, with Bechdel invoking the Daedalus myth five times in the opening pages to depict her father as a labyrinthine creator akin to the engineer who built the Minotaur's maze, trapping himself in secrecy.[36] She casts Bruce as Daedalus and herself as Icarus, inverting the son's fatal flight to suggest her own "escape" into lesbian identity contrasts his entrapment, while also alluding to the Minotaur as a symbol of monstrous paternal impulses.[37] These classical references ground the memoir's Oedipal tensions in archetypal father-son (or father-daughter) conflicts, drawing from Joyce's Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which Bruce assigns Alison, linking his life to Stephen Dedalus's quest for autonomy amid paternal dominance.[38] Proust's In Search of Lost Time recurs as a motif of involuntary memory and sexual awakening, with Bruce beginning the novel the year before his 1980 death, prompting Bechdel to draw parallels between Proust's madeleine epiphany and her own retrospective insights into his affairs.[39] Fitzgerald's works, especially The Great Gatsby, evoke Bruce's ill-fated pursuits, as Bechdel notes biographical overlaps like Fitzgerald's age at death matching her father's (44 years), and uses Gatsby's illusory grandeur to analogize Bruce's funeral-home facade hiding homosexual liaisons with boys and men.[40] Additional allusions to Oscar Wilde highlight themes of aestheticism and scandal, reinforcing Bruce's identification with literary figures whose lives ended in disgrace, while Camus and Henry James appear to probe existential isolation and unreliable narration.[34] Cultural allusions extend beyond literature to mid-20th-century American artifacts, such as 1950s advertisements and Army manuals that Bruce collects, symbolizing his era's repressive heteronormativity, though these serve more as visual foils than direct intertexts.[41] Bechdel's method avoids reductive equivalence, instead layering allusions to reveal the contingency of memory—facts verifiable through her diaries and letters—against fictional archetypes, critiquing how her father's literary enthusiasms both connected and alienated them.[42] This approach, while innovative, relies on reader familiarity, potentially limiting accessibility but enriching analysis for those versed in the canon.[43]Artistic Style and Structure

Fun Home employs a non-linear narrative structure, interweaving Bechdel's reflections on her father's death and closeted homosexuality with flashbacks to her childhood and parallel developments in her own lesbian identity during college. This approach uses scene-to-scene transitions in panel sequences to juxtapose disparate time periods, revealing connections between events separated by years. Aspect-to-aspect layouts further slow the pace, emphasizing mood and multiple perspectives on grief or secrecy, such as in sequences depicting funerals or hidden desires.[44] The memoir's seven chapters are framed by literary allusions, drawing parallels between Bechdel's family dynamics and works like James Joyce's Ulysses or Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time, which structure thematic explorations of inheritance, deception, and self-discovery. Visual and textual quotations from literature, film stills (e.g., from It's a Wonderful Life), and family documents create a collage-like density, blending autobiography with intertextual critique to underscore the unreliability of memory and the constructed nature of truth.[45] Bechdel's artistic style features clean, cartoonish line work for narrative panels, evoking subjective recollection, contrasted with meticulous cross-hatching and shading for rendered photographs and realistic elements, which mimic archival objectivity. Family photos are redrawn in photorealistic detail across double pages or as chapter headers, using dense ink textures to differentiate "evidence" from interpretive illustration, as in depictions of childhood snapshots or evidentiary letters. This dual approach, rooted in traditional ink and watercolor techniques with visible imperfections, invites readers into an over-the-shoulder viewpoint, mirroring Bechdel's analytical gaze on her past.[44][46][47]