Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aerojet Rocketdyne

View on WikipediaAerojet Rocketdyne is a subsidiary of American defense company L3Harris that manufactures rocket, hypersonic, and electric propulsive systems for space, defense, civil and commercial applications.[3][4][2] Aerojet traces its origins to the General Tire and Rubber Company (later renamed GenCorp, Inc. as it diversified) established in 1915, while Rocketdyne was created as a division of North American Aviation in 1955.[5][6] Aerojet Rocketdyne was formed in 2013 when Aerojet and Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne were merged, following the latter's acquisition by GenCorp, Inc. from Pratt & Whitney.[7][8] Aerojet Rocketdyne was acquired by L3Harris in July 2023 for $4.7 billion.

Key Information

History

[edit]Background: Aerojet

[edit]Several decades after it began manufacturing rubber products, General Tire & Rubber diversified into broadcasting and aeronautics.

In the 1940s, the Aerojet company began experimenting with various rocket designs. For a solid-fuel rocket, they needed binders, and turned to General Tire & Rubber for assistance. General became a partner in the company.

Radio broadcasting began with the purchase of several radio networks starting in 1943. In 1952, its purchase of WOR-TV expanded the broadcast business into television. In 1953, General Tire & Rubber bought the RKO Radio Pictures movie studio.[9] All of its media and entertainment holdings were organized into the RKO General division.

Due to the studio and rocket businesses, General Tire & Rubber came to own a great deal of property in California. Its internal facilities management unit began commercializing its operations, landing General Tire & Rubber in the real estate business. This started when Aerojet-General Corporation acquired approximately 12,600 acres (51 km2) of land in Eastern Sacramento County. Aerojet converted these former gold fields into one of the premier rocket manufacturing and testing facilities in the Western world. However, most of this land was used to provide safe buffer zones for Aerojet's testing and manufacturing operations. Later, as the need for these facilities and safety zones decreased, the property became available for other uses. Located 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Sacramento along U.S. Highway 50, the properties were valuable, being in a key growth corridor in the region. Approximately 6,000 acres (24 km2) of the Aerojet lands are now being planned as a community called Easton. Easton Development Company LLC was formed to assist in the process.[10]

Background: Rocketdyne

[edit]

In 1955, North American Aviation spun off Rocketdyne, a developer of rocket motors that built upon research conducted into the German V-2 Rocket after World War II. Rocketdyne would become a major supplier for NASA, producing the Rocketdyne F-1 engine for the Saturn V rocket of the Apollo Space Program as well as the RS-25 engine of the Space Shuttle program and its successor the Space Launch System (SLS) program.

Aerojet Rocketdyne engines have contributed to every successful NASA Mars mission, including powering the launch, entry, descent, and landing phases of the Perseverance rover mission.[11]

Name change

[edit]

In 1984, General Tire created a parent holding company, GenCorp, Inc., for its various business ventures.

The main subsidiaries were:

- General Tire and Rubber

- RKO General, the broadcast arm of the conglomerate;

- DiversiTech General, a manufacturer of tennis balls and polymer products, including automotive soundproofing and home wallpapers.

- Aerojet General, a defense (missile) contractor.

Through its RKO General subsidiary, the company also held stakes in:

- Frontier Airlines.

- RKO bottlers, which operated Pepsi-Cola distributorships; and several resorts and hotels, including the Westward Look resort in Tucson, Arizona.

Disconglomeration

[edit]Faced with a hostile takeover attempt, among other difficulties, GenCorp, Inc. shed some of its long-held units in the late 1980s.

RKO General ran into difficulties with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) during license renewal proceedings in the late 1980s. The FCC was reluctant to renew the broadcast licenses, due to widespread lying to advertisers and regulators. As a result of the protracted proceedings, GenCorp sold RKO General's broadcast properties beginning in 1987.

GenCorp, Inc. also sold its former flagship, General Tire, to German tire manufacturer Continental AG in order to concentrate on Aerojet.

In 1999, GenCorp, Inc. spun off its Decorative & Building Products and Performance Chemicals businesses. GenCorp, Inc. formed OMNOVA Solutions Inc. into a separate, publicly traded company, and transferred those businesses into it.

GenCorp, Inc.'s two remaining businesses, as of 2008, were Aerojet and Easton Real Estate.[12]

Pension problems and leadership changes

[edit]GenCorp, Inc. withdrew its over-funded pension during the real estate boom years of 2006 and 2007. The real estate bust caused an underfunding of the pension plan of over $300 million. This caused a freeze of its pension plan on February 1, 2009, and an end to 401(k) match on January 15, 2009. The move was expected to save the company 29 million a year.[13]

In March 2008, hedge fund Steel Partners II, which owned 14% of GenCorp, Inc., made an agreement that saw Terry J. Hall step down as CEO and gave Steel Partners II control of three board seats plus the selection of the new CEO (who would also hold a board seat). Steel Partners II had previously attempted a hostile takeover in 2004, and forced the deal after complaining about "significant underperformance and deterioration of share price". Aerojet President J. Scott Neish was named interim CEO.[14]

In January 2010, Scott Seymour, the former head of Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems from 2002 to 2008, was appointed permanent CEO of GenCorp, Inc. and Neish resigned.[15]

Aeronautics expansion

[edit]

In July 2012, GenCorp, Inc. agreed to buy rocket engine producer Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne from United Technologies Corporation for $550 million.[16][17][18] The FTC approved the deal on June 10, 2013, and it closed on June 17.[19] [20][21][22] GenCorp, Inc. was later renamed Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc on April 27, 2015.[23]

Abandoned acquisition by Lockheed Martin

[edit]On December 20, 2020, it was announced that Lockheed Martin would acquire the company for $4.4 billion.[24] The acquisition was expected to close in first quarter of 2022,[25] but this received opposition from Raytheon Technologies. Later the FTC sued to block this deal on a 4–0 vote in January 2022 on grounds that this would eliminate the largest independent maker of rocket motors[26][27] and Lockheed subsequently abandoned the deal in February 2022.[28][29]

Acquisition by L3Harris

[edit]In December 2022, L3Harris Technologies agreed to buy the company for $4.7 billion in cash.[30] The acquisition was completed in July 2023.[31] L3Harris named former CTO Ross Niebergall as president of the new Aerojet Rocketdyne business segment,[2] which would now be headquartered in Palm Bay, Florida.[32]

Products

[edit]

Current engines

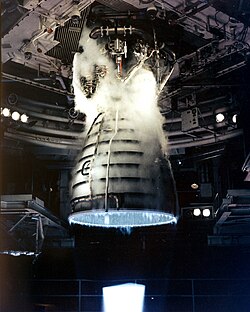

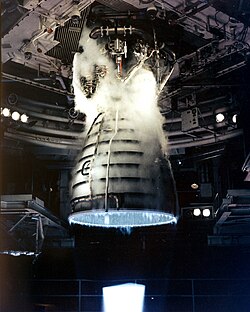

[edit]- RS-25 (LH2/LOX) – Previously known as the Space Shuttle main engine (SSME), it was the reusable main engine developed by Rocketdyne for the now-retired Space Shuttle. Remaining RS-25D engines are planned for use on early Space Launch System rocket launches after which an expendable version, RS-25E will be developed for follow-on SLS launches.

- RL10 (LH2/LOX) – Developed by Pratt & Whitney and currently used on the Centaur upper stage for the Atlas V. It is also currently used on the Space Launch System on the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) and will be used on the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) in the future. Formerly used on the upper stage for the Delta IV, the Centaur upper stage for Titan, the S-IV upper stage for the Saturn I, the vertical-landing McDonnell Douglas DC-X "Delta Clipper". It was intended to serve as the main propulsion engine for the proposed Altair lunar lander. Two RL-10 engines are used on Centaur V upper stage of ULA Vulcan.

- R-4D (MMH/NTO) – 100 lbf (exact thrust depends on variant) hypergolic thruster, originally developed by Marquardt as RCS thrusters for the Apollo SM and LM. Currently used as secondary engines on the Orion European Service Module, and as apogee motors on various satellite buses.

- MR103G — 0.2 lb hydrazine monopropellant thruster

- MR111g — 1 lb hydrazine monopropellant thruster

- MR106L — 5-7 lb hydrazine monopropellant thruster

- MR107M — 45 lb hydrazine monopropellant thruster

- Blue Origin CCE (solid rocket motor or SRM) — the Blue Origin New Shepard Crew Capsule Escape Solid Rocket Motor is built by Aerojet Rocketdyne.[33]

Former production engines and others

[edit]- Rocketdyne F-1 (RP-1/LOX) – The main engine of the first stage of the Saturn V rocket used in the Apollo program. The most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine ever developed.[34]

- Rocketdyne J-2 (LH2/LOX) – Used on the upper stage of the Saturn IB and second and upper stages of Saturn V.

- SJ61 (JP-7/ingested air) – A dual-mode ramjet/scramjet engine flown on the Boeing X-51 hypersonic demonstration vehicle.

- AJ10 (Aerozine 50/N2O4) – Second stage engine for the Delta II, used as the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engine for the Space Shuttle, and the main engine for the European Orion Service Module.

- AR1 (RP-1/LOX) – A proposed 500,000-pound-force-class (2,200 kN) thrust RP-1/LOX oxidizer-rich staged combustion cycle engine.[35]

- Rocketdyne H-1 (RP-1/LOX) – A first stage engine flown on the Saturn I and Saturn IB launch vehicles.

- RS-27 (RP-1/LOX) – A first stage engine flown on the Delta 2000 launch vehicle.

- RS-27A (RP-1/LOX) – A first stage engine flown on the Delta II and Delta III.

- RS-68 (LH2/LOX) – A first stage engine flown on the Delta IV, designed as a simplified version of the RS-25 due to its expendable usage. It is the largest hydrogen-fueled rocket engine ever flown.

- J-2X (LH2/LOX) – An engine that was originally being developed for the Ares I's upper stage before the cancellation of the Constellation program. The engine was considered for the Space Launch System's Exploration Upper Stage before being replaced with a cluster of four RL10s. It is based on the Rocketdyne J-2.

- Baby Bantam (RP-1/LOX) – An 22 kN (5,000 lbf) thrust engine.[36] In June 2014, Aerojet Rocketdyne announced that they had "manufactured and successfully tested an engine which had been entirely 3D printed".

- AJ-26 (RP-1/LOX) – Rebranded and modified NK-33 engines imported from Russia. Used as first stage engine for the Antares before being replaced by the RD-181.

- AJ-60A (Solid – HTPB) – A solid rocket motor formerly used for the Atlas V launch vehicle, until being replaced by the Northrop Grumman GEM-63 in 2021.[37]

- AR-22 (LH2/LOX) – An engine in development from 2017 to 2020 for the XS-1 spacecraft, also known as the Phantom Express. The engine is based on the RS-25 and utilizing parts remaining in Aerojet Rocketdyne and NASA inventories from earlier versions of the RS-25. Two of the engines would have been built for the spaceplane.[38] Boeing pulled out of the project in January 2020, effectively ending it.[39]

In development

[edit]X3 ion thruster

[edit]On 13 October 2017, it was reported that Aerojet Rocketdyne completed a keystone demonstration on a new X3 ion thruster, which is a central part of the XR-100 system for the NextSTEP program.[40][41] The X3 ion thruster was designed by the University of Michigan[42] and is being developed in partnership with the University of Michigan, NASA, and the Air Force. The X3 is a Hall-effect thruster operating at over 100 kW of power. During the demonstration, it broke records for the maximum power output, thrust and operating current achieved by a Hall thruster to date.[40] It operated at a range of power from 5 kW to 102 kW, with electric current of up to 260 amperes. It generated 5.4 newtons of thrust, "which is the highest level of thrust achieved by any plasma thruster to date".[40][43] A novelty in its design is that it incorporates three plasma channels, each a few centimeters deep, nested around one another in concentric rings.[41] The system is 227 kg (500 lb) and almost 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) in diameter.[40]

Other notable products

[edit]Multi-mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator

[edit]Aerojet Rocketdyne is the prime contractor to the US Department of Energy for the Multi-mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. The first flight MMRTG is currently powering the Mars Curiosity Rover, and a second flight unit powers the Perseverance Rover.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings 2022 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Weisgerber, Marcus (28 July 2023). "On Day 1 of ownership, L3Harris pledges to invest in Aerojet Rocketdyne". Defense One. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "About Us | Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc". Archived from the original on 2023-04-14. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ "Hypersonics | Aerojet Rocketdyne". www.rocket.com. Archived from the original on 2022-04-25. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc. (21 April 2015). "GenCorp Announces Effective Date for Name and Stock Ticker Symbol Change". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release).

- ^ "Rocketdyne | American company | Britannica".

- ^ "Two engine rivals merge into Aerojet Rocketdyne". Spaceflight Now. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Roop, Lee (June 17, 2013). "Here's how Aerojet Rocketdyne might bring 5,000 new aerospace engineering jobs to Huntsville". www.al.com. Alabama Media Group. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ "R. K. O. STUDIO SOLD TO GENERAL TIRE; Hughes Stock Acquired for $25,000,000 in Cash -- Use as TV Film Center Hinted General Tire Buys R.K.O. Studio From Hughes for 25 Million Cash". The New York Times. Associated Press. 1955-07-19. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- ^ "Easton Plan Home". Archived from the original on March 18, 2009.

- ^ "NASA Perseverance's Mission to Mars Propelled by Aerojet Rocketdyne | Aerojet Rocketdyne". Archived from the original on 2023-04-14. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ^ "Home – Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc". www.aerojetrocketdyne.com.

- ^ "GenCorp Freezes Pension Plan". The Rancho Cordova Post. Archived from the original on 2011-01-06. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ^ "GenCorp board faces shake-up: CEO steps down; Steel Partners II, a hedge fund, wins directors' seats". TCMNet News. Thomson Dialog NewsEdge. 6 March 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "Northrop Veteran Takes Helm of Gencorp, Aerojet". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Los Angeles Times; "Rocketdyne sold to GenCorp" . accessed 12 December 2012

- ^ "GenCorp to buy rocket manufacturer Rocketdyne". Flightglobal. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "Who's Where", Aviation Week & Space Technology, January 1, 2007

- ^ "Home – The Fly". thefly.com.

- ^ "Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne Cuts 100 Jobs – SpaceRef Business". spaceref.biz. Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

- ^ "U.S. clears GenCorp, Rocketdyne deal after Defense Department request". Reuters. Washington, DC. June 10, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ "GenCorp Closes Rocketdyne Buy". Yahoo! Finance. Zacks Equity Research. June 17, 2013.

- ^ "History". Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ "Lockheed makes a solid rocket motor splash, buying Aerojet Rocketdyne for $4.4B". Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ "Lockheed predicts Aerojet acquisition will close next quarter". Yahoo! News. Defense News. 2021-10-26. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Stone, Mike (20 December 2020). "Lockheed Martin inks $4.4 billion deal to acquire Aerojet Rocketdyne". Reuters.

- ^ "FTC Sues to Block Lockheed Martin Acquisition of Aerojet Rocketdyne". The Wall Street Journal. 25 January 2022.

- ^ Johnsson, Julie (2022-02-13). "Lockheed Scraps Aerojet Deal After FTC Takes Tough Merger Stance". MSN.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (February 17, 2021). "Raytheon to challenge Lockheed Martin's acquisition of Aerojet Rocketdyne". Space News. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ Gomez, Nathan; Ghosh, Kanjyik (December 19, 2022). "Defense firm L3Harris to buy Aerojet for $4.7 bln with eye on missile demand". Reuters.

- ^ Losey, Stephen (July 28, 2023). "L3Harris closes purchase of Aerojet Rocketdyne". Defense News.

- ^ Berman, Dave. "L3Harris completes $4.7B deal for rocket-engine maker Aerojet, which will based in Palm Bay". Florida Today. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Motor Plays Key Role in Successful Blue Origin In-Flight Crew Escape Test". SpaceRef.com. 6 October 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ W. David Woods, How Apollo Flew to the Moon, Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-71675-6, p. 19

- ^ "AR1 Booster Engine". Aerojet Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne 3D Prints An Entire Engine in Just Three Parts". 3dprint.com. 2014-06-26. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Atlas 5 rocket launches infrared missile detection satellite for U.S. Space Force". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Selected As Main Propulsion Provider for Boeing and DARPA Experimental Spaceplane". Aerojet Rocketdyne. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Farewell, Phantom Express: Boeing is pulling out of DARPA space plane program". Yahoo! News. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Pultarova, Tereza (13 October 2017). "Ion Thruster Prototype Breaks Records in Tests, Could Send Humans to Mars". Space.com. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- ^ a b Mcalpine, Katherine (19 February 2016). "Hall thruster a serious contender to get humans to Mars". PhysOrg. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- ^ "PEPL Thrusters: X3". University of Michigan. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-03-11.

- ^ Wall, Mike (26 April 2016). "Next-Gen Propulsion System Gets $67 Million from NASA". Space.com. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

External links

[edit]- Historical business data for Aerojet Rocketdyne:

- SEC filings

- Official website

Aerojet Rocketdyne

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins of Aerojet

Aerojet originated from pioneering rocket research at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory of the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT) during the late 1930s. A team led by aerodynamics expert Theodore von Kármán, including Frank J. Malina, Jack Parsons, Edward Forman, and Homer Bushey—derisively nicknamed the "Suicide Squad" for the explosive risks of their early experiments—pursued solid-propellant rockets to enhance aircraft performance. Their efforts centered on jet-assisted take-off (JATO) units, designed to provide auxiliary thrust for heavily loaded military planes facing short runways, addressing limitations in conventional propeller-driven aviation. Initial static firings occurred in the Arroyo Seco area near Pasadena, with the first successful full-duration test of a JATO motor on October 31, 1939.[7] U.S. Army Air Corps interest intensified following a dramatic JATO demonstration on August 16, 1941, where a solid-fuel unit boosted an Ercoupe aircraft from a standing start. This proof-of-concept secured initial contracts for further development and production, necessitating a shift from academic prototyping to commercial manufacturing. On March 19, 1942, von Kármán, Malina, Parsons, Forman, Martin Summerfield, and attorney Andrew G. Haley incorporated Aerojet Engineering Corporation in Pasadena, California, with von Kármán as president and Malina as treasurer. The venture capitalized on wartime urgency, as Allied forces required propulsion innovations for air superiority.[8] Aerojet received its inaugural production contract from the Army just three months after incorporation, producing JATO units that proved vital for operations like the Pacific Theater island-hopping campaigns. The company established its first dedicated manufacturing site on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena, scaling up from rudimentary GALCIT setups to industrial output of rocket motors. This foundation positioned Aerojet as one of the earliest dedicated rocket propulsion firms, driven by empirical testing and military imperatives rather than speculative theory.[8][9]Origins of Rocketdyne

Rocketdyne was established on November 7, 1955, as a dedicated division of North American Aviation (NAA) to consolidate and advance the company's rocket engine development efforts, initially focusing on liquid-propellant engines for military missiles.[10] The division was headquartered in Canoga Park, California, and built upon NAA's prior propulsion work, which had accelerated during the early Cold War era amid U.S. Air Force demands for intercontinental-range weapons.[11] The roots of Rocketdyne's technology trace to NAA's post-World War II examination of captured German V-2 rocket engines. In 1946, NAA's Aerophysics Laboratory received two V-2/A-4 engines, which engineers disassembled, analyzed, and used as a basis for constructing three American replicas adapted to U.S. manufacturing standards and propellants.[12] This hands-on reverse-engineering provided foundational knowledge in high-thrust, liquid-fueled rocket design, emphasizing turbopump-fed systems using liquid oxygen (LOX) and alcohol or kerosene. NAA's early testing occurred at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, a 2,500-acre site leased in the Simi Hills in 1947 for static engine firings.[13] A pivotal precursor was NAA's engine development for the Navaho supersonic cruise missile program, launched in response to a 1945 U.S. Army Air Forces request for long-range guided weapons. The Navaho required a rocket-boosted ramjet configuration, leading NAA to design its first large-scale liquid rocket engine, the NAA 75-110 (also designated XLR43-NA-6), which delivered approximately 75,000 pounds of thrust using LOX and 75-octane gasoline.[14][15] This engine, tested from 1949 onward, addressed challenges in scalable thrust and reliable ignition, directly influencing subsequent designs like the Redstone A-6 engine and establishing NAA's expertise in clustered engine configurations for boost phases. By 1955, the accumulation of these projects—coupled with contracts for Atlas and Thor ballistic missiles—necessitated a specialized entity, formalizing Rocketdyne as NAA's propulsion arm with an initial emphasis on kerosene-LOX engines for intermediate-range applications.[16]Formation of Aerojet Rocketdyne

GenCorp Inc., the parent company of Aerojet, entered into a definitive agreement on July 23, 2012, to acquire substantially all operations of Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne from United Technologies Corporation for approximately $550 million.[17][18] The acquisition aimed to combine Aerojet's expertise in solid rocket propulsion and missile systems with Rocketdyne's liquid rocket engine technologies, creating a unified entity capable of competing more effectively in the aerospace and defense propulsion market.[19] The deal faced regulatory scrutiny but closed on June 14, 2013, marking the official formation of Aerojet Rocketdyne as the resulting business unit under GenCorp.[19][20] This merger integrated Rocketdyne's facilities, including its Canoga Park operations in California, with Aerojet's existing sites, roughly doubling GenCorp's revenue in the propulsion sector to about $2.2 billion annually.[21] The new organization retained key leadership from both entities, with Aerojet's CEO Tim Reiley transitioning to head the combined company.[22] Following the merger, GenCorp rebranded the propulsion division as Aerojet Rocketdyne, emphasizing its role in developing engines for space launch vehicles, missiles, and defense systems.[23] In 2014, GenCorp itself changed its corporate name to Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc., to align with the core business.[24] The formation strengthened U.S. domestic capabilities in rocket propulsion amid growing demand for reliable engines in national security and exploration programs.[2]Key Milestones and Challenges

Aerojet's development of jet-assisted take-off (JATO) units during World War II marked an early milestone, enabling military aircraft to launch from short runways and carriers by providing supplemental thrust from solid-fuel rockets.[2] These units, first tested in the early 1940s, addressed critical operational limitations in combat aviation and laid the foundation for Aerojet's expertise in solid propulsion.[25] Similarly, Rocketdyne's inception in 1955 as a North American Aviation division led to the F-1 engine's qualification in 1964, which powered the Saturn V's first stage during the Apollo program, delivering over 1.5 million pounds of thrust per engine to enable the 1969 moon landing.[26] The 2013 acquisition of Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne by GenCorp for approximately $550 million unified liquid and solid propulsion capabilities under Aerojet Rocketdyne, combining Aerojet's solid rocket motors with Rocketdyne's high-performance engines like the RS-25, which had propelled every Space Shuttle mission since 1981 with 512 flights by 2011.[2] This merger aimed to streamline development for programs such as NASA's Space Launch System (SLS), where RS-25 engines underwent successful full-duration hot-fire tests in 2017, validating reusability for deep-space missions.[27] Aerojet Rocketdyne's contributions extended to defense, powering the HAWK missile system since the Cold War era, with motors remaining operational over 60 years later.[2] Challenges emerged in supply chain and production scaling, particularly for solid rocket motors in the 2020s, where delays in delivering components like nozzles and igniters created backlogs for programs including Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (GMLRS).[28] By 2022, internal board conflicts and antitrust scrutiny derailed Lockheed Martin's $4.4 billion acquisition bid, as the Federal Trade Commission cited risks of reduced competition in missile propulsion.[29] Aerojet's market share erosion to competitors like Northrop Grumman in legacy solid motor contracts compounded financial pressures, necessitating the $4.7 billion acquisition by L3Harris in 2023 to bolster capacity and stabilize operations.[30] These issues highlighted vulnerabilities in subcontractor dependencies and regulatory hurdles amid rising defense demands.[31]Corporate Restructuring and Acquisitions

In July 2012, GenCorp Inc., the parent company of Aerojet General Corporation, announced an agreement to acquire Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne from United Technologies Corporation for $550 million, subject to adjustments for working capital and other items.[32] The transaction, financed through a combination of cash and debt, was completed in June 2013 following regulatory approvals, including clearance from the Federal Trade Commission after its investigation confirmed no significant anticompetitive effects.[33] This merger integrated Rocketdyne's liquid rocket engine expertise with Aerojet's solid rocket motor capabilities, forming Aerojet Rocketdyne as a new subsidiary focused on propulsion systems; GenCorp subsequently rebranded itself as Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings Inc. in 2014 to reflect the entity's centrality to its operations.[34] To streamline operations and reduce costs amid competitive pressures in the aerospace sector, Aerojet Rocketdyne consolidated its six existing business units into two primary divisions—Space and Defense—in June 2016, projecting annual savings of $8 million through eliminated redundancies in management and support functions.[35] This restructuring emphasized core competencies in propulsion for government contracts while maintaining separate leadership for space-related (e.g., launch vehicles and in-space systems) and defense-related (e.g., missile and tactical applications) portfolios.[36] Aerojet Rocketdyne pursued minor acquisitions to bolster niche technologies, including the purchase of 3D Material Technologies in March 2019 to enhance additive manufacturing for propulsion components, though such deals remained limited compared to its core organic growth.[37] In December 2020, Lockheed Martin Corporation agreed to acquire Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings for approximately $4.4 billion in an all-stock transaction aimed at vertical integration for missile and space programs, but the deal faced regulatory scrutiny over potential risks to competition in hypersonic and solid rocket motor markets.[38] The U.S. Department of Defense expressed concerns about reduced supplier diversity, and the Federal Trade Commission challenged the merger in January 2022, leading Lockheed Martin to terminate the agreement on February 13, 2022, without penalty.[39] [40] Following the failed Lockheed bid, L3Harris Technologies Inc. announced in December 2022 an all-cash acquisition of Aerojet Rocketdyne for $58 per share, valuing the deal at $4.7 billion including net debt, to expand capabilities in missile defense and space propulsion.[41] The transaction cleared regulatory hurdles without FTC opposition, reflecting assessments that it would not substantially lessen competition, and closed on July 28, 2023, integrating Aerojet Rocketdyne as a wholly owned subsidiary under L3Harris' Aerojet Rocketdyne segment.[4] [42] Post-acquisition, L3Harris increased investments in Aerojet Rocketdyne's facilities by 40% year-over-year as of 2024, focusing on manufacturing modernization for solid rocket motors and hypersonic systems.[5]Products and Technologies

Launch Vehicle Engines

Aerojet Rocketdyne develops and produces liquid-propellant rocket engines critical for U.S. launch vehicles, emphasizing high-thrust hydrogen-oxygen cycles for core and upper stages. These engines power vehicles from NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) to commercial rockets like United Launch Alliance's Atlas V and Delta IV.[43][44] The RS-25, evolved from the Space Shuttle Main Engine, serves as the core stage propulsion for SLS, with four engines delivering over 2 million pounds of thrust combined during ascent.[45] Each employs a staged-combustion cycle using liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, achieving specific impulse exceeding 450 seconds in vacuum.[43] NASA contracted Aerojet Rocketdyne in May 2020 for 18 additional RS-25 engines to support Artemis missions, targeting cost reductions through modern manufacturing.[46] Hot-fire tests of new-production units occurred as recently as June 2025 at Stennis Space Center.[47] The RL10 family powers upper stages across multiple launch systems, including Centaur for Atlas V and Vulcan, as well as SLS's Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage.[44] First operational in 1963, the RL10 generates about 24,750 pounds of thrust via an expansible nozzle for vacuum optimization.[48] Variants like the RL10C-1-1A support Vulcan's debut, while the RL10E-1 incorporates 3D-printed thrust chambers with 98% fewer parts for enhanced reliability and reduced costs; deliveries began in November 2024.[49][50] Over 500 RL10 engines have flown, accumulating decades of heritage in precise orbital insertions.[51] The RS-68A propelled Delta IV first stages, producing 705,000 pounds of thrust in a gas-generator cycle prioritizing affordability over peak efficiency.[52] Designed for liquid hydrogen and oxygen, it supported 28 missions before final acceptance testing in April 2021, aligning with Delta IV's phase-out.[53] This engine's simpler architecture enabled lower production costs compared to staged-combustion alternatives.[54]Solid Rocket Motors and Missile Propulsion

Aerojet Rocketdyne produces solid rocket motors (SRMs) featuring lightweight graphite composite cases, advanced nozzles, and high-energy, long-life propellants customized for specific missions, enabling reliable propulsion for tactical missiles, strategic systems, air defense, and missile defense applications.[55] These motors support a range of defense programs, including hypersonic systems, and have powered historical intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) such as Minuteman I and Polaris variants A1 through A3.[55] [56] In strategic missile propulsion, Aerojet Rocketdyne supplies the SR-19 as the second stage for the Minuteman III ICBM, with the redesigned eSR-19 variant incorporating a lighter filament-wound composite case and enhanced performance; a qualification static fire test of the eSR-19 at Edwards Air Force Base in June 2023 validated its capabilities for powering both stages of the Missile Defense Agency's next-generation Medium Range Ballistic Missile (MRBM) target vehicle.[57] [58] The company also provides propulsion for the LGM-35A Sentinel ICBM program.[1] For missile defense and tactical systems, Aerojet Rocketdyne delivers solid rocket boost motors for the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system, reaching the 1,000th unit delivery in June 2024 ahead of schedule, alongside Divert and Attitude Control Systems; advanced SRM technology propels the PAC-3 MSE interceptor, while motors support the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS).[1] [3] [59] Additional tactical applications include Javelin anti-tank missiles under a five-year contract extension valued up to $292 million and Stinger air defense missiles.[55] Recent advancements include successful testing of the eSR-73 large SRM and Zeus 1/2 low-cost solid rocket motors in a November 2024 flight test, demonstrating versatility for various targets; Aerojet Rocketdyne was selected in May 2024 as propulsion provider for the Missile Defense Agency's Next Generation Interceptor (NGI).[55] [60] [6] To address supply chain demands, the U.S. Department of Defense awarded a $215.6 million cooperative agreement in April 2023 to expand SRM production facilities in Camden, Arkansas; Huntsville, Alabama; and Virginia, incorporating modernization and digital tools for higher output.[55]In-Space Propulsion Systems

Aerojet Rocketdyne produces monopropellant chemical thrusters using hydrazine for in-space attitude control and maneuvering, with thrust levels ranging from 0.02 to 700 pounds-force and over 19,000 units delivered across satellite and planetary missions.[61] The MR-103 series, delivering 1 N (0.2 lbf) thrust, features a specific impulse of 202 to 224 seconds, steady-state thrust of 0.19 to 1.13 N, and a total mass of 0.33 kg, with more than 1,500 flight units produced over four decades for applications including small satellite propulsion.[62] These systems have supported missions such as NASA's Curiosity and Perseverance rover sky cranes for precise landing maneuvers.[61] Bipropellant thrusters from Aerojet Rocketdyne employ monomethylhydrazine (MMH) and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO), providing thrust from 2.5 to 40,000 pounds-force for orbit raising, major velocity adjustments, and crewed vehicle operations.[61] The R-4D engine, at 100 pounds-force thrust, has achieved a 100% success rate in over 390 apogee-insertion missions, including legacy roles in Apollo Service Modules and Space Shuttle orbital maneuvering subsystems.[61] Current applications include the Orion and Starliner spacecraft for in-space maneuvering.[61] Additionally, the company has advanced green monopropellant technology with AF-M315E, offering 50% greater density-specific impulse than hydrazine; the GR-1 (1 N) and GR-22 (22 N) thrusters powered the 2019 Green Propellant Infusion Mission (GPIM) satellite, demonstrating reduced toxicity and higher efficiency in orbit adjustments.[63][64] In electric propulsion, Aerojet Rocketdyne's solar electric systems, primarily Hall effect thrusters, enable efficient station-keeping and trajectory transfers for satellites and deep-space vehicles.[65] The Advanced Electric Propulsion System (AEPS), a 12 kW Hall thruster developed with NASA, powers the Lunar Gateway's Power and Propulsion Element with three units, each more than twice as capable as prior 4.5 kW systems; qualification testing began in July 2023 at NASA's Glenn Research Center, encompassing vibration, thermal, and 23,000-hour wear simulations to support a 15-year mission lifespan.[66] Other offerings include the flight-proven XR-5 Hall subsystem for commercial satellites like AEHF and GEOStar-3, the 7 kW NEXT-C gridded ion thruster used on NASA's 2022 DART mission, and the high-power XR-100 nested Hall system tested to 100 kW under NASA's NextSTEP program for potential cargo transfer applications.[65] Arcjet variants like the MR-510 have flown on over 55 spacecraft for electrothermal augmentation of hydrazine performance.[65]Developmental and Emerging Technologies

Aerojet Rocketdyne has prioritized research and development in hypersonic propulsion systems, leveraging scramjet engines and solid rocket boosters for high-speed applications. In April 2022, an advanced scramjet engine produced by the company powered the successful flight test of the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency's (DARPA) Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC), demonstrating sustained operation at Mach 5+ velocities. Subsequent ground tests of an 18-foot scramjet achieved thrust exceeding 13,000 pounds, marking record performance levels over a 12-month evaluation period. In June 2021, Aerojet Rocketdyne conducted a full-scale static test of a solid rocket motor for DARPA's ground-launched hypersonic system, validating boost-phase capabilities for rapid acceleration to hypersonic speeds.[67][68][69] Additive manufacturing advancements are central to the company's hypersonic efforts, enabling rapid prototyping and reduced production timelines. In May 2024, the U.S. Department of Defense awarded Aerojet Rocketdyne a contract to develop a "Powder-in, Engine-out™" hypersonic propulsion prototype using 3D printing, with delivery anticipated within 36 months to streamline manufacturing from raw materials to functional engines. This approach builds on prior collaborations, such as a December 2020 test series with the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) that achieved hypersonic flow milestones in a dual-mode ramjet/scramjet configuration. Additionally, in May 2022, the company secured selection from Lockheed Martin to supply boosters for hypersonic missile programs, integrating these technologies into operational weapon systems.[70][71][72] In nuclear propulsion, Aerojet Rocketdyne is developing engine systems for both nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) and nuclear electric propulsion (NEP) to enable deep-space missions, including human exploration of Mars. These efforts focus on high-efficiency, fission-based systems that provide greater specific impulse than chemical rockets, reducing transit times and propellant mass. Company engineers have emphasized NTP's potential for faster Mars round trips, with ongoing work aligned to NASA and Department of Defense requirements for reliable, high-thrust nuclear engines.[73][74] Emerging in-space propulsion technologies include advanced electric systems, such as Hall-effect thrusters and solar electric propulsion variants, designed for sustainable satellite maneuvering and lunar operations. Aerojet Rocketdyne's advanced electric propulsion supports extended mission durations with lower mass penalties compared to traditional chemical systems, incorporating additive manufacturing for cost-effective production. These developments complement chemical in-space options like the AF-M315E monopropellant, which offers higher performance density for small satellites and has undergone on-orbit demonstrations.[1][61][75]Contributions to Major Programs

Space Exploration and NASA Missions

Aerojet Rocketdyne's involvement in NASA's Apollo program stemmed from its predecessors' development of critical propulsion systems. Rocketdyne's F-1 engines powered the S-IC first stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle, with five engines per rocket delivering approximately 7.5 million pounds of thrust to enable the Moon landings between 1969 and 1972.[76] Aerojet's AJ10-137 engine served as the service propulsion system for the Apollo Service Module, providing 20,000 pounds of thrust for orbital maneuvers and trans-Earth injection burns on all crewed missions.[77] Additionally, Aerojet's R-4D thrusters handled reaction control for precise attitude adjustments throughout the missions.[78] The company's engines played a central role in the Space Shuttle program from 1981 to 2011. Rocketdyne's RS-25 engines, known as Space Shuttle Main Engines, powered every one of the 135 shuttle missions, throttling between 65% and 109% of rated power while burning liquid hydrogen and oxygen to produce over 418,000 pounds of thrust each at liftoff.[79] These reusable engines underwent extensive refurbishment between flights, contributing to the program's operational reliability. Aerojet provided hypergolic thrusters for the Orbital Maneuvering System and Reaction Control System, enabling on-orbit adjustments and reentry targeting.[2] In contemporary NASA efforts, Aerojet Rocketdyne supplies propulsion for the Artemis program and deep-space exploration. The RS-25 engines, upgraded for higher performance, power the core stage of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, as demonstrated in the uncrewed Artemis I launch on November 16, 2022, where four engines fired for over eight minutes.[79] The RL10 engine propels the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage atop SLS Block 1 vehicles, with deliveries completed for early Artemis missions to provide upper-stage velocity increments for lunar trajectories.[80] For the Orion spacecraft, Aerojet Rocketdyne furnishes the AJ10-based engines for the European Service Module, supporting propulsion needs on Artemis II and subsequent crewed flights.[81] The RL10 has also powered upper stages in planetary missions, including NASA's MAVEN orbiter to Mars launched in 2013.[82]| Engine | Program/Mission | Role | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-1 | Apollo (Saturn V) | First stage | 1.5 million lbf thrust per engine; 5 per vehicle[76] |

| AJ10-137 | Apollo Service Module | Main propulsion | 20,000 lbf thrust; Isp 314.5 s[77] |

| RS-25 | Space Shuttle, SLS/Artemis | Main engines | 418,000 lbf thrust at sea level; reusable design[79] |

| RL10 | SLS ICPS, planetary probes | Upper stage | 24,750 lbf vacuum thrust; restartable[44] |