Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Liquid hydrogen

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Hydrogen

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Liquid hydrogen | |||

| Other names

Hydrogen (cryogenic liquid), Refrigerated hydrogen; LH2, para-hydrogen

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1966 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H2(l) | |||

| Molar mass | 2.016 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Density | 0.07085 g/cm3 (4.423 lb/cu ft)[1] | ||

| Melting point | −259.14 °C (−434.45 °F; 14.01 K)[2] | ||

| Boiling point | −252.87 °C (−423.17 °F; 20.28 K)[2] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling:[3] | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H220, H280 | |||

| P210, P377, P381, P403 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| 571 °C (1,060 °F; 844 K)[2] | |||

| Explosive limits | LEL 4.0%; UEL 74.2% (in air)[2] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

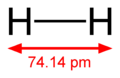

Liquid hydrogen (H2(l)) is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecular H2 form.[4]

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point of 33 K. However, for it to be in a fully liquid state at atmospheric pressure, H2 needs to be cooled to 20.28 K (−252.87 °C; −423.17 °F).[5] A common method of obtaining liquid hydrogen involves a compressor resembling a jet engine in both appearance and principle. Liquid hydrogen is typically used as a concentrated form of hydrogen storage. Storing it as liquid takes less space than storing it as a gas at normal temperature and pressure. However, the liquid density is very low compared to other common fuels. Once liquefied, it can be maintained as a liquid for some time in thermally insulated containers.[6]

There are two spin isomers of hydrogen: Room temperature hydrogen is 75% orthohydrogen. At cryogenic temperature it converts exothermically to parahydrogen. The thermodynamic lowest energy state for liquid hydrogen consists of 99.79% parahydrogen and 0.21% orthohydrogen.[5]. To avoid that the exothermic heat release occurs in storage, and thereby causes excessive boil-off, catalytic conversion to parahydrogen during liquification is employed.

Hydrogen requires a theoretical minimum of 3.3 kWh/kg (12 MJ/kg) to liquefy, and 3.9 kWh/kg (14 MJ/kg) including converting the hydrogen to the para isomer. Existing liquification facilities use 10–13 kWh/kg (36–47 MJ/kg) compared to a 33 kWh/kg (119 MJ/kg) heating value of hydrogen.[7]. More recent work shows future facilities are expected to cut the specific energy demand by half to 6.5 kWh/kg (23 MJ/kg) [8]

History

[edit]

In 1885, Zygmunt Florenty Wróblewski published hydrogen's critical temperature as 33 K (−240.2 °C; −400.3 °F); critical pressure, 13.3 standard atmospheres (195 psi); and boiling point, 23 K (−250.2 °C; −418.3 °F).

Hydrogen was liquefied by James Dewar in 1898 by using regenerative cooling and his invention, the vacuum flask. The first synthesis of the stable isomer form of liquid hydrogen, parahydrogen, was achieved by Paul Harteck and Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer in 1929.

Spin isomers of hydrogen

[edit]The two nuclei in a dihydrogen molecule can have two different spin states. Parahydrogen, in which the two nuclear spins are antiparallel, is more stable than orthohydrogen, in which the two are parallel. At room temperature, gaseous hydrogen is mostly in the ortho isomeric form due to thermal energy, but an ortho-enriched mixture is only metastable when liquified at low temperature. It slowly undergoes an exothermic reaction to become the para isomer, with enough energy released as heat to cause some of the liquid to boil.[9] To prevent loss of the liquid during long-term storage, it is therefore intentionally converted to the para isomer as part of the production process, typically using a catalyst such as iron(III) oxide, activated carbon, platinized asbestos, rare earth metals, uranium compounds, chromium(III) oxide, or some nickel compounds.[9]

Uses

[edit]Liquid hydrogen is a common liquid rocket fuel for rocketry application and is used by NASA and the U.S. Air Force, which operate a large number of liquid hydrogen tanks with an individual capacity up to 3.8 million liters (1 million U.S. gallons).[10]

In most rocket engines fueled by liquid hydrogen, it first cools the nozzle and other parts before being mixed with the oxidizer, usually liquid oxygen, and burned to produce water with traces of ozone and hydrogen peroxide. Practical H2–O2 rocket engines run fuel-rich so that the exhaust contains some unburned hydrogen. This reduces combustion chamber and nozzle erosion. It also reduces the molecular weight of the exhaust, which can increase specific impulse, despite the incomplete combustion.

Liquid hydrogen can be used as the fuel for an internal combustion engine or fuel cell. Various submarines, including the Type 212 submarine, Type 214 submarine, and others, and concept hydrogen vehicles have been built using this form of hydrogen, such as the DeepC, BMW H2R, and others. Due to its similarity, builders can sometimes modify and share equipment with systems designed for liquefied natural gas (LNG). Liquid hydrogen is being investigated as a zero carbon fuel for aircraft. Because of the lower volumetric energy, the hydrogen volumes needed for combustion are large. Unless direct injection is used, a severe gas-displacement effect also hampers maximum breathing and increases pumping losses.

Liquid hydrogen is also used to cool neutrons to be used in neutron scattering. Since neutrons and hydrogen nuclei have similar masses, kinetic energy exchange per interaction is maximum (elastic collision). Finally, superheated liquid hydrogen was used in many bubble chamber experiments.

The first thermonuclear bomb, Ivy Mike, used liquid deuterium, also known as hydrogen-2, for nuclear fusion.

Properties

[edit]The product of hydrogen combustion in a pure oxygen environment is solely water vapor. However, the high combustion temperatures and present atmospheric nitrogen can result in the breaking of N≡N bonds, forming toxic NOx if no exhaust scrubbing is done.[11] Since water is often considered harmless to the environment, an engine burning it can be considered "zero emissions". In aviation, however, water vapor emitted in the atmosphere contributes to global warming (to a lesser extent than CO2).[12] Liquid hydrogen also has a much higher specific energy than gasoline, natural gas, or diesel.[13]

The density of liquid hydrogen is only 70.85 kg/m3 (at 20 K), a relative density of just 0.07. Although the specific energy is more than twice that of other fuels, this gives it a remarkably low volumetric energy density, many fold lower.

Liquid hydrogen requires cryogenic storage technology such as special thermally insulated containers and requires special handling common to all cryogenic fuels. This is similar to, but more severe than liquid oxygen. Even with thermally insulated containers it is difficult to keep such a low temperature, and the hydrogen will gradually leak away (typically at a rate of 1% per day[13]). It also shares many of the same safety issues as other forms of hydrogen, as well as being cold enough to liquefy, or even solidify atmospheric oxygen, which can be an explosion hazard.

The triple point of hydrogen is at 13.81 K[5] and 7.042 kPa.[14]

Safety

[edit]Due to its cold temperatures, liquid hydrogen is a hazard for cold burns. Hydrogen itself is biologically inert and its only human health hazard as a vapor is displacement of oxygen, resulting in asphyxiation, and its very high flammability and ability to detonate when mixed with air. Because of its flammability, liquid hydrogen should be kept away from heat or flame unless ignition is intended. Unlike ambient-temperature gaseous hydrogen, which is lighter than air, hydrogen recently vaporized from liquid is so cold that it is heavier than air and can form flammable heavier-than-air air–hydrogen mixtures.

An indirect safety risk exists due to the cryogenic temperature being lower than the boiling point of oxygen. Exposure of insuffiently thermally insulated liquid hydrogen containments can result in air condensing on the outside of the containment, leading to oxygen enrichment that can spontaneously ignite flammable materials.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Thermophysical Properties of Hydrogen, nist.gov, accessed 2012-09-14

- ^ a b c d Information specific to liquid hydrogen Archived 2009-07-17 at the Wayback Machine, harvard.edu, accessed 2009-06-12

- ^ GHS: GESTIS 007010

- ^ "We've Got (Rocket) Chemistry, Part 1". NASA Blog. 15 April 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ a b c IPTS-1968, iupac.org, accessed 2020-01-01

- ^ "Liquid Hydrogen Delivery". Energy.gov. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ^ Gardiner, Monterey (2009-10-26). DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program Record: Energy requirements for hydrogen gas compression and liquefaction as related to vehicle storage needs (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Energy.

- ^ (Report) https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/9013_energy_requirements_for_hydrogen_gas_compression.pdfhttps://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/278177/reporting.

{{cite report}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b "Liquefaction of "Permanent" Gases" (PDF of lecture notes). 2011. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ Flynn, Thomas (2004). Cryogenic Engineering, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded. CRC Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-0-203-02699-1.

- ^ Lewis, Alastair C. (2021-07-22). "Optimising air quality co-benefits in a hydrogen economy: a case for hydrogen-specific standards for NOx emissions". Environmental Science: Atmospheres. 1 (5): 201–207. Bibcode:2021ESAt....1..201L. doi:10.1039/D1EA00037C. ISSN 2634-3606. S2CID 236732702.

- ^ Nojoumi, H. (2008-11-10). "Greenhouse gas emissions assessment of hydrogen and kerosene-fueled aircraft propulsion". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 34 (3): 1363–1369. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.11.017.

- ^ a b Hydrogen As an Alternative Fuel Archived 2008-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. Almc.army.mil. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

- ^ Cengel, Yunus A. and Turner, Robert H. (2004). Fundamentals of thermal-fluid sciences, McGraw-Hill, p. 78, ISBN 0-07-297675-6