Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Regulation of gene expression

View on Wikipedia

Regulation of gene expression, or gene regulation,[1] includes a wide range of mechanisms that are used by cells to increase or decrease the production of specific gene products (protein or RNA). Sophisticated programs of gene expression are widely observed in biology, for example to trigger developmental pathways, respond to environmental stimuli, or adapt to new food sources. Virtually any step of gene expression can be modulated, from transcriptional initiation, to RNA processing, and to the post-translational modification of a protein. Often, one gene regulator controls another, and so on, in a gene regulatory network.

Gene regulation is essential for viruses, prokaryotes and eukaryotes as it increases the versatility and adaptability of an organism by allowing the cell to express protein when needed. Although as early as 1951, Barbara McClintock showed interaction between two genetic loci, Activator (Ac) and Dissociator (Ds), in the color formation of maize seeds, the first discovery of a gene regulation system is widely considered to be the identification in 1961 of the lac operon, discovered by François Jacob and Jacques Monod, in which some enzymes involved in lactose metabolism are expressed by E. coli only in the presence of lactose and absence of glucose.

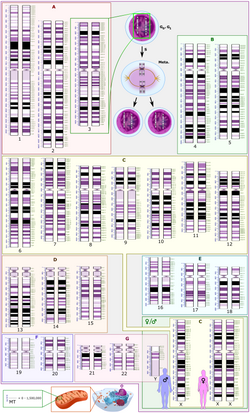

In multicellular organisms, gene regulation drives cellular differentiation and morphogenesis in the embryo, leading to the creation of different cell types that possess different gene expression profiles from the same genome sequence. Although this does not explain how gene regulation originated, evolutionary biologists include it as a partial explanation of how evolution works at a molecular level, and it is central to the science of evolutionary developmental biology ("evo-devo").

Regulated stages of gene expression

[edit]Any step of gene expression may be modulated, from signaling to transcription to post-translational modification of a protein. The following is a list of stages where gene expression is regulated, where the most extensively utilized point is transcription initiation, the first stage in transcription:[citation needed]

Modification of DNA

[edit]

In eukaryotes, the accessibility of large regions of DNA can depend on its chromatin structure, which can be altered as a result of histone modifications directed by DNA methylation, ncRNA, or DNA-binding protein. Hence these modifications may up or down regulate the expression of a gene. Some of these modifications that regulate gene expression are inheritable and are referred to as epigenetic regulation.[citation needed]

Structural

[edit]Transcription of DNA is dictated by its structure. In general, the density of its packing is indicative of the frequency of transcription. Octameric protein complexes called histones together with a segment of DNA wound around the eight histone proteins (together referred to as a nucleosome) are responsible for the amount of supercoiling of DNA, and these complexes can be temporarily modified by processes such as phosphorylation or more permanently modified by processes such as methylation. Such modifications are considered to be responsible for more or less permanent changes in gene expression levels.[2]

Chemical

[edit]Methylation of DNA is a common method of gene silencing. DNA is typically methylated by methyltransferase enzymes on cytosine nucleotides in a CpG dinucleotide sequence (also called "CpG islands" when densely clustered). Analysis of the pattern of methylation in a given region of DNA (which can be a promoter) can be achieved through a method called bisulfite mapping. Methylated cytosine residues are unchanged by the treatment, whereas unmethylated ones are changed to uracil. The differences are analyzed by DNA sequencing or by methods developed to quantify SNPs, such as Pyrosequencing (Biotage) or MassArray (Sequenom), measuring the relative amounts of C/T at the CG dinucleotide. Abnormal methylation patterns are thought to be involved in oncogenesis.[3]

Histone acetylation is also an important process in transcription. Histone acetyltransferase enzymes (HATs) such as CREB-binding protein also dissociate the DNA from the histone complex, allowing transcription to proceed. Often, DNA methylation and histone deacetylation work together in gene silencing. The combination of the two seems to be a signal for DNA to be packed more densely, lowering gene expression.[citation needed]

Regulation of transcription

[edit]

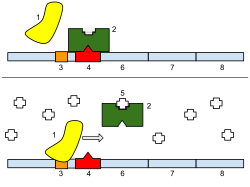

Regulation of transcription thus controls when transcription occurs and how much RNA is created. Transcription of a gene by RNA polymerase can be regulated by several mechanisms. Specificity factors alter the specificity of RNA polymerase for a given promoter or set of promoters, making it more or less likely to bind to them (i.e., sigma factors used in prokaryotic transcription). Repressors bind to the Operator, coding sequences on the DNA strand that are close to or overlapping the promoter region, impeding RNA polymerase's progress along the strand, thus impeding the expression of the gene. The image to the right demonstrates regulation by a repressor in the lac operon. General transcription factors position RNA polymerase at the start of a protein-coding sequence and then release the polymerase to transcribe the mRNA. Activators enhance the interaction between RNA polymerase and a particular promoter, encouraging the expression of the gene. Activators do this by increasing the attraction of RNA polymerase for the promoter, through interactions with subunits of the RNA polymerase or indirectly by changing the structure of the DNA. Enhancers are sites on the DNA helix that are bound by activators in order to loop the DNA bringing a specific promoter to the initiation complex. Enhancers are much more common in eukaryotes than prokaryotes, where only a few examples exist (to date).[4] Silencers are regions of DNA sequences that, when bound by particular transcription factors, can silence expression of the gene.

Regulation by RNA

[edit]RNA can be an important regulator of gene activity, e.g. by microRNA (miRNA), antisense-RNA, or long non-coding RNA (lncRNA). LncRNAs differ from mRNAs in the sense that they have specified subcellular locations and functions. They were first discovered to be located in the nucleus and chromatin, and the localizations and functions are highly diverse now. Some still reside in chromatin where they interact with proteins. While this lncRNA ultimately affects gene expression in neuronal disorders such as Parkinson, Huntington, and Alzheimer disease, others, such as, PNCTR(pyrimidine-rich non-coding transcriptors), play a role in lung cancer. Given their role in disease, lncRNAs are potential biomarkers and may be useful targets for drugs or gene therapy, although there are no approved drugs that target lncRNAs yet. The number of lncRNAs in the human genome remains poorly defined, but some estimates range from 16,000 to 100,000 lnc genes.[5]

Epigenetic gene regulation

[edit]

Epigenetics refers to the modification of genes that is not changing the DNA or RNA sequence. Epigenetic modifications are also a key factor in influencing gene expression. They occur on genomic DNA and histones and their chemical modifications regulate gene expression in a more efficient manner. There are several modifications of DNA (usually methylation) and more than 100 modifications of RNA in mammalian cells." Those modifications result in altered protein binding to DNA and a change in RNA stability and translation efficiency.[6]

Special cases in human biology and disease

[edit]Regulation of transcription in cancer

[edit]In vertebrates, the majority of gene promoters contain a CpG island with numerous CpG sites.[7] When many of a gene's promoter CpG sites are methylated the gene becomes silenced.[8] Colorectal cancers typically have 3 to 6 driver mutations and 33 to 66 hitchhiker or passenger mutations.[9] However, transcriptional silencing may be of more importance than mutation in causing progression to cancer. For example, in colorectal cancers about 600 to 800 genes are transcriptionally silenced by CpG island methylation (see regulation of transcription in cancer). Transcriptional repression in cancer can also occur by other epigenetic mechanisms, such as altered expression of microRNAs.[10] In breast cancer, transcriptional repression of BRCA1 may occur more frequently by over-expressed microRNA-182 than by hypermethylation of the BRCA1 promoter (see Low expression of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancers).

Regulation of transcription in addiction

[edit]One of the cardinal features of addiction is its persistence. The persistent behavioral changes appear to be due to long-lasting changes, resulting from epigenetic alterations affecting gene expression, within particular regions of the brain.[11] Drugs of abuse cause three types of epigenetic alteration in the brain. These are (1) histone acetylations and histone methylations, (2) DNA methylation at CpG sites, and (3) epigenetic downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs.[11][12] (See Epigenetics of cocaine addiction for some details.)

Chronic nicotine intake in mice alters brain cell epigenetic control of gene expression through acetylation of histones. This increases expression in the brain of the protein FosB, important in addiction.[13] Cigarette addiction was also studied in about 16,000 humans, including never smokers, current smokers, and those who had quit smoking for up to 30 years.[14] In blood cells, more than 18,000 CpG sites (of the roughly 450,000 analyzed CpG sites in the genome) had frequently altered methylation among current smokers. These CpG sites occurred in over 7,000 genes, or roughly a third of known human genes. The majority of the differentially methylated CpG sites returned to the level of never-smokers within five years of smoking cessation. However, 2,568 CpGs among 942 genes remained differentially methylated in former versus never smokers. Such remaining epigenetic changes can be viewed as "molecular scars"[12] that may affect gene expression.

In rodent models, drugs of abuse, including cocaine,[15] methamphetamine,[16][17] alcohol[18] and tobacco smoke products,[19] all cause DNA damage in the brain. During repair of DNA damages some individual repair events can alter the methylation of DNA and/or the acetylations or methylations of histones at the sites of damage, and thus can contribute to leaving an epigenetic scar on chromatin.[20]

Such epigenetic scars likely contribute to the persistent epigenetic changes found in addiction.

Regulation of transcription in learning and memory

[edit]

In mammals, methylation of cytosine (see Figure) in DNA is a major regulatory mediator. Methylated cytosines primarily occur in dinucleotide sequences where cytosine is followed by a guanine, a CpG site. The total number of CpG sites in the human genome is approximately 28 million.[21] and generally about 70% of all CpG sites have a methylated cytosine.[22]

In a rat, a painful learning experience, contextual fear conditioning, can result in a life-long fearful memory after a single training event.[23] Cytosine methylation is altered in the promoter regions of about 9.17% of all genes in the hippocampus neuron DNA of a rat that has been subjected to a brief fear conditioning experience.[24] The hippocampus is where new memories are initially stored.

Methylation of CpGs in a promoter region of a gene represses transcription[25] while methylation of CpGs in the body of a gene increases expression.[26] TET enzymes play a central role in demethylation of methylated cytosines. Demethylation of CpGs in a gene promoter by TET enzyme activity increases transcription of the gene.[27]

When contextual fear conditioning is applied to a rat, more than 5,000 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) (of 500 nucleotides each) occur in the rat hippocampus neural genome both one hour and 24 hours after the conditioning in the hippocampus.[24] This causes about 500 genes to be up-regulated (often due to demethylation of CpG sites in a promoter region) and about 1,000 genes to be down-regulated (often due to newly formed 5-methylcytosine at CpG sites in a promoter region). The pattern of induced and repressed genes within neurons appears to provide a molecular basis for forming the first transient memory of this training event in the hippocampus of the rat brain.[24]

Post-transcriptional regulation

[edit]After the DNA is transcribed and mRNA is formed, there must be some sort of regulation on how much the mRNA is translated into proteins. Cells do this by modulating the capping, splicing, addition of a Poly(A) Tail, the sequence-specific nuclear export rates, and, in several contexts, sequestration of the RNA transcript. These processes occur in eukaryotes but not in prokaryotes. This modulation is a result of a protein or transcript that, in turn, is regulated and may have an affinity for certain sequences.

Three prime untranslated regions and microRNAs

[edit]Three prime untranslated regions (3'-UTRs) of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) often contain regulatory sequences that post-transcriptionally influence gene expression.[28] Such 3'-UTRs often contain both binding sites for microRNAs (miRNAs) as well as for regulatory proteins. By binding to specific sites within the 3'-UTR, miRNAs can decrease gene expression of various mRNAs by either inhibiting translation or directly causing degradation of the transcript. The 3'-UTR also may have silencer regions that bind repressor proteins that inhibit the expression of a mRNA.

The 3'-UTR often contains miRNA response elements (MREs). MREs are sequences to which miRNAs bind. These are prevalent motifs within 3'-UTRs. Among all regulatory motifs within the 3'-UTRs (e.g. including silencer regions), MREs make up about half of the motifs.

As of 2014, the miRBase web site,[29] an archive of miRNA sequences and annotations, listed 28,645 entries in 233 biologic species. Of these, 1,881 miRNAs were in annotated human miRNA loci. miRNAs were predicted to have an average of about four hundred target mRNAs (affecting expression of several hundred genes).[30] Freidman et al.[30] estimate that >45,000 miRNA target sites within human mRNA 3'-UTRs are conserved above background levels, and >60% of human protein-coding genes have been under selective pressure to maintain pairing to miRNAs.

Direct experiments show that a single miRNA can reduce the stability of hundreds of unique mRNAs.[31] Other experiments show that a single miRNA may repress the production of hundreds of proteins, but that this repression often is relatively mild (less than 2-fold).[32][33]

The effects of miRNA dysregulation of gene expression seem to be important in cancer.[34] For instance, in gastrointestinal cancers, a 2015 paper identified nine miRNAs as epigenetically altered and effective in down-regulating DNA repair enzymes.[35]

The effects of miRNA dysregulation of gene expression also seem to be important in neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and autism spectrum disorders.[36][37][38]

Regulation of translation

[edit]The translation of mRNA can also be controlled by a number of mechanisms, mostly at the level of initiation. Recruitment of the small ribosomal subunit can indeed be modulated by mRNA secondary structure, antisense RNA binding, or protein binding. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, a large number of RNA binding proteins exist, which often are directed to their target sequence by the secondary structure of the transcript, which may change depending on certain conditions, such as temperature or presence of a ligand (aptamer). Some transcripts act as ribozymes and self-regulate their expression.

Examples of gene regulation

[edit]- Enzyme induction is a process in which a molecule (e.g., a drug) induces (i.e., initiates or enhances) the expression of an enzyme.

- The induction of heat shock proteins in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.

- The Lac operon is an interesting example of how gene expression can be regulated.

- Viruses, despite having only a few genes, possess mechanisms to regulate their gene expression, typically into an early and late phase, using collinear systems regulated by anti-terminators (lambda phage) or splicing modulators (HIV).

- Gal4 is a transcriptional activator that controls the expression of GAL1, GAL7, and GAL10 (all of which code for the metabolic of galactose in yeast). The GAL4/UAS system has been used in a variety of organisms across various phyla to study gene expression.[39]

Developmental biology

[edit]A large number of studied regulatory systems come from developmental biology. Examples include:

- The colinearity of the Hox gene cluster with their nested antero-posterior patterning

- Pattern generation of the hand (digits - interdigits): the gradient of sonic hedgehog (secreted inducing factor) from the zone of polarizing activity in the limb, which creates a gradient of active Gli3, which activates Gremlin, which inhibits BMPs also secreted in the limb, results in the formation of an alternating pattern of activity as a result of this reaction–diffusion system.

- Somitogenesis is the creation of segments (somites) from a uniform tissue (Pre-somitic Mesoderm). They are formed sequentially from anterior to posterior. This is achieved in amniotes possibly by means of two opposing gradients, Retinoic acid in the anterior (wavefront) and Wnt and Fgf in the posterior, coupled to an oscillating pattern (segmentation clock) composed of FGF + Notch and Wnt in antiphase.[40]

- Sex determination in the soma of a Drosophila requires the sensing of the ratio of autosomal genes to sex chromosome-encoded genes, which results in the production of sexless splicing factor in females, resulting in the female isoform of doublesex.[41]

Circuitry

[edit]Up-regulation and down-regulation

[edit]Up-regulation is a process which occurs within a cell triggered by a signal (originating internal or external to the cell), which results in increased expression of one or more genes and as a result the proteins encoded by those genes. Conversely, down-regulation is a process resulting in decreased gene and corresponding protein expression.

- Up-regulation occurs, for example, when a cell is deficient in some kind of receptor. In this case, more receptor protein is synthesized and transported to the membrane of the cell and, thus, the sensitivity of the cell is brought back to normal, reestablishing homeostasis.

- Down-regulation occurs, for example, when a cell is overstimulated by a neurotransmitter, hormone, or drug for a prolonged period of time, and the expression of the receptor protein is decreased in order to protect the cell (see also tachyphylaxis).

Inducible vs. repressible systems

[edit]

Gene Regulation can be summarized by the response of the respective system:

- Inducible systems - An inducible system is off unless there is the presence of some molecule (called an inducer) that allows for gene expression. The molecule is said to "induce expression". The manner by which this happens is dependent on the control mechanisms as well as differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

- Repressible systems - A repressible system is on except in the presence of some molecule (called a corepressor) that suppresses gene expression. The molecule is said to "repress expression". The manner by which this happens is dependent on the control mechanisms as well as differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

The GAL4/UAS system is an example of both an inducible and repressible system. Gal4 binds an upstream activation sequence (UAS) to activate the transcription of the GAL1/GAL7/GAL10 cassette. On the other hand, a MIG1 response to the presence of glucose can inhibit GAL4 and therefore stop the expression of the GAL1/GAL7/GAL10 cassette.[42]

Theoretical circuits

[edit]- Repressor/Inducer: an activation of a sensor results in the change of expression of a gene

- negative feedback: the gene product downregulates its own production directly or indirectly, which can result in

- keeping transcript levels constant/proportional to a factor

- inhibition of run-away reactions when coupled with a positive feedback loop

- creating an oscillator by taking advantage in the time delay of transcription and translation, given that the mRNA and protein half-life is shorter

- positive feedback: the gene product upregulates its own production directly or indirectly, which can result in

- signal amplification

- bistable switches when two genes inhibit each other and both have positive feedback

- pattern generation

Study methods

[edit]

In general, most experiments investigating differential expression used whole cell extracts of RNA, called steady-state levels, to determine which genes changed and by how much. These are, however, not informative of where the regulation has occurred and may mask conflicting regulatory processes (see post-transcriptional regulation), but it is still the most commonly analysed (quantitative PCR and DNA microarray).

When studying gene expression, there are several methods to look at the various stages. In eukaryotes these include:

- The local chromatin environment of the region can be determined by ChIP-chip analysis by pulling down RNA Polymerase II, Histone 3 modifications, Trithorax-group protein, Polycomb-group protein, or any other DNA-binding element to which a good antibody is available.

- Epistatic interactions can be investigated by synthetic genetic array analysis

- Due to post-transcriptional regulation, transcription rates and total RNA levels differ significantly. To measure the transcription rates nuclear run-on assays can be done and newer high-throughput methods are being developed, using thiol labelling instead of radioactivity.[43]

- Only 5% of the RNA polymerised in the nucleus exits,[44] and not only introns, abortive products, and non-sense transcripts are degradated. Therefore, the differences in nuclear and cytoplasmic levels can be seen by separating the two fractions by gentle lysis.[45]

- Alternative splicing can be analysed with a splicing array or with a tiling array (see DNA microarray).

- All in vivo RNA is complexed as RNPs. The quantity of transcripts bound to specific protein can be also analysed by RIP-Chip. For example, DCP2 will give an indication of sequestered protein; ribosome-bound gives and indication of transcripts active in transcription (although a more dated method, called polysome fractionation, is still popular in some labs)

- Protein levels can be analysed by Mass spectrometry, which can be compared only to quantitative PCR data, as microarray data is relative and not absolute.

- RNA and protein degradation rates are measured by means of transcription inhibitors (actinomycin D or α-Amanitin) or translation inhibitors (Cycloheximide), respectively.

See also

[edit]- Artificial transcription factors (small molecules that mimic transcription factor protein)

- Cellular model

- Conserved non-coding DNA sequence

- Enhancer (genetics)

- Gene structure

- Spatiotemporal gene expression

- Regulator gene glucosyltransferases (Rgg/SHP) systems

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Can genes be turned on and off in cells?". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016.

- ^ Bell JT, Pai AA, Pickrell JK, Gaffney DJ, Pique-Regi R, Degner JF, et al. (2011). "DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines". Genome Biology. 12 (1) R10. doi:10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r10. PMC 3091299. PMID 21251332.

- ^ Vertino PM, Spillare EA, Harris CC, Baylin SB (April 1993). "Altered chromosomal methylation patterns accompany oncogene-induced transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells" (PDF). Cancer Research. 53 (7): 1684–9. PMID 8453642.

- ^ Austin S, Dixon R (June 1992). "The prokaryotic enhancer binding protein NTRC has an ATPase activity which is phosphorylation and DNA dependent". The EMBO Journal. 11 (6): 2219–28. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05281.x. PMC 556689. PMID 1534752.

- ^ Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL, Huarte M (February 2021). "Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 22 (2): 96–118. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00315-9. ISSN 1471-0072. PMC 7754182. PMID 33353982.

- ^ Kan RL, Chen J, Sallam T (July 2021). "Crosstalk between epitranscriptomic and epigenetic mechanisms in gene regulation". Trends in Genetics. 38 (2): 182–193. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2021.06.014. PMC 9093201. PMID 34294427. S2CID 236200223.

- ^ Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL (January 2006). "A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (5): 1412–7. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1412S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510310103. PMC 1345710. PMID 16432200.

- ^ Bird A (January 2002). "DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory". Genes & Development. 16 (1): 6–21. doi:10.1101/gad.947102. PMID 11782440.

- ^ Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Kinzler KW (March 2013). "Cancer genome landscapes". Science. 339 (6127): 1546–58. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1546V. doi:10.1126/science.1235122. PMC 3749880. PMID 23539594.

- ^ Tessitore A, Cicciarelli G, Del Vecchio F, Gaggiano A, Verzella D, Fischietti M, et al. (2014). "MicroRNAs in the DNA Damage/Repair Network and Cancer". International Journal of Genomics. 2014 820248. doi:10.1155/2014/820248. PMC 3926391. PMID 24616890.

- ^ a b Nestler EJ (January 2014). "Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction". Neuropharmacology. 76 Pt B: 259–68. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004. PMC 3766384. PMID 23643695.

- ^ a b Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (October 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–37. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

- ^ Levine A, Huang Y, Drisaldi B, Griffin EA, Pollak DD, Xu S, et al. (November 2011). "Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (107): 107ra109. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. PMC 4042673. PMID 22049069.

- ^ Joehanes R, Just AC, Marioni RE, Pilling LC, Reynolds LM, Mandaviya PR, et al. (October 2016). "Epigenetic Signatures of Cigarette Smoking". Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 9 (5): 436–447. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001506. PMC 5267325. PMID 27651444.

- ^ de Souza MF, Gonçales TA, Steinmetz A, Moura DJ, Saffi J, Gomez R, Barros HM (April 2014). "Cocaine induces DNA damage in distinct brain areas of female rats under different hormonal conditions". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 41 (4): 265–9. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12218. PMID 24552452. S2CID 20849951.

- ^ Johnson Z, Venters J, Guarraci FA, Zewail-Foote M (June 2015). "Methamphetamine induces DNA damage in specific regions of the female rat brain". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 42 (6): 570–5. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12404. PMID 25867833. S2CID 24182756.

- ^ Tokunaga I, Ishigami A, Kubo S, Gotohda T, Kitamura O (August 2008). "The peroxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in methamphetamine-treated rat brain". The Journal of Medical Investigation. 55 (3–4): 241–5. doi:10.2152/jmi.55.241. PMID 18797138.

- ^ Rulten SL, Hodder E, Ripley TL, Stephens DN, Mayne LV (July 2008). "Alcohol induces DNA damage and the Fanconi anemia D2 protein implicating FANCD2 in the DNA damage response pathways in brain". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 32 (7): 1186–96. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00673.x. PMID 18482162.

- ^ Adhami N, Chen Y, Martins-Green M (October 2017). "Biomarkers of disease can be detected in mice as early as 4 weeks after initiation of exposure to third-hand smoke levels equivalent to those found in homes of smokers". Clinical Science. 131 (19): 2409–2426. doi:10.1042/CS20171053. PMID 28912356.

- ^ Dabin J, Fortuny A, Polo SE (June 2016). "Epigenome Maintenance in Response to DNA Damage". Molecular Cell. 62 (5): 712–27. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.006. PMC 5476208. PMID 27259203.

- ^ Lövkvist C, Dodd IB, Sneppen K, Haerter JO (June 2016). "DNA methylation in human epigenomes depends on local topology of CpG sites". Nucleic Acids Research. 44 (11): 5123–32. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw124. PMC 4914085. PMID 26932361.

- ^ Jabbari K, Bernardi G (May 2004). "Cytosine methylation and CpG, TpG (CpA) and TpA frequencies". Gene. 333: 143–9. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.043. PMID 15177689.

- ^ Kim JJ, Jung MW (2006). "Neural circuits and mechanisms involved in Pavlovian fear conditioning: a critical review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 30 (2): 188–202. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.005. PMC 4342048. PMID 16120461.

- ^ a b c Duke CG, Kennedy AJ, Gavin CF, Day JJ, Sweatt JD (July 2017). "Experience-dependent epigenomic reorganization in the hippocampus". Learning & Memory. 24 (7): 278–288. doi:10.1101/lm.045112.117. PMC 5473107. PMID 28620075.

- ^ Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Pääbo S, Rebhan M, Schübeler D (April 2007). "Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome". Nat. Genet. 39 (4): 457–66. doi:10.1038/ng1990. PMID 17334365. S2CID 22446734.

- ^ Yang X, Han H, De Carvalho DD, Lay FD, Jones PA, Liang G (October 2014). "Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer". Cancer Cell. 26 (4): 577–90. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.028. PMC 4224113. PMID 25263941.

- ^ Maeder ML, Angstman JF, Richardson ME, Linder SJ, Cascio VM, Tsai SQ, Ho QH, Sander JD, Reyon D, Bernstein BE, Costello JF, Wilkinson MF, Joung JK (December 2013). "Targeted DNA demethylation and activation of endogenous genes using programmable TALE-TET1 fusion proteins". Nat. Biotechnol. 31 (12): 1137–42. doi:10.1038/nbt.2726. PMC 3858462. PMID 24108092.

- ^ Ogorodnikov A, Kargapolova Y, Danckwardt S (June 2016). "Processing and transcriptome expansion at the mRNA 3' end in health and disease: finding the right end". Pflügers Archiv. 468 (6): 993–1012. doi:10.1007/s00424-016-1828-3. PMC 4893057. PMID 27220521.

- ^ miRBase.org

- ^ a b Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP (January 2009). "Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs". Genome Research. 19 (1): 92–105. doi:10.1101/gr.082701.108. PMC 2612969. PMID 18955434.

- ^ Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, et al. (February 2005). "Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs". Nature. 433 (7027): 769–73. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..769L. doi:10.1038/nature03315. PMID 15685193. S2CID 4430576.

- ^ Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N (September 2008). "Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs". Nature. 455 (7209): 58–63. Bibcode:2008Natur.455...58S. doi:10.1038/nature07228. PMID 18668040. S2CID 4429008.

- ^ Baek D, Villén J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP (September 2008). "The impact of microRNAs on protein output". Nature. 455 (7209): 64–71. Bibcode:2008Natur.455...64B. doi:10.1038/nature07242. PMC 2745094. PMID 18668037.

- ^ Palmero EI, de Campos SG, Campos M, de Souza NC, Guerreiro ID, Carvalho AL, Marques MM (July 2011). "Mechanisms and role of microRNA deregulation in cancer onset and progression". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 34 (3): 363–70. doi:10.1590/S1415-47572011000300001. PMC 3168173. PMID 21931505.

- ^ Bernstein C, Bernstein H (May 2015). "Epigenetic reduction of DNA repair in progression to gastrointestinal cancer". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 7 (5): 30–46. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v7.i5.30. PMC 4434036. PMID 25987950.

- ^ Maffioletti E, Tardito D, Gennarelli M, Bocchio-Chiavetto L (2014). "Micro spies from the brain to the periphery: new clues from studies on microRNAs in neuropsychiatric disorders". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 8: 75. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00075. PMC 3949217. PMID 24653674.

- ^ Mellios N, Sur M (2012). "The Emerging Role of microRNAs in Schizophrenia and Autism Spectrum Disorders". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 3: 39. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00039. PMC 3336189. PMID 22539927.

- ^ Geaghan M, Cairns MJ (August 2015). "MicroRNA and Posttranscriptional Dysregulation in Psychiatry". Biological Psychiatry. 78 (4): 231–9. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.009. hdl:1959.13/1335073. PMID 25636176.

- ^ Barnett JA (July 2004). "A history of research on yeasts 7: enzymic adaptation and regulation". Yeast. 21 (9): 703–46. doi:10.1002/yea.1113. PMID 15282797. S2CID 36606279.

- ^ Dequéant ML, Pourquié O (May 2008). "Segmental patterning of the vertebrate embryonic axis". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 9 (5): 370–82. doi:10.1038/nrg2320. PMID 18414404. S2CID 2526914.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2003). Developmental biology, 7th ed., Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, 65–6. ISBN 0-87893-258-5.

- ^ Nehlin JO, Carlberg M, Ronne H (November 1991). "Control of yeast GAL genes by MIG1 repressor: a transcriptional cascade in the glucose response". The EMBO Journal. 10 (11): 3373–7. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04901.x. PMC 453065. PMID 1915298.

- ^ Cheadle C, Fan J, Cho-Chung YS, Werner T, Ray J, Do L, et al. (May 2005). "Control of gene expression during T cell activation: alternate regulation of mRNA transcription and mRNA stability". BMC Genomics. 6 75. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-6-75. PMC 1156890. PMID 15907206.

- ^ Jackson DA, Pombo A, Iborra F (February 2000). "The balance sheet for transcription: an analysis of nuclear RNA metabolism in mammalian cells". FASEB Journal. 14 (2): 242–54. doi:10.1096/fasebj.14.2.242. PMID 10657981. S2CID 23518786.

- ^ Schwanekamp JA, Sartor MA, Karyala S, Halbleib D, Medvedovic M, Tomlinson CR (2006). "Genome-wide analyses show that nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA levels are differentially affected by dioxin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression. 1759 (8–9): 388–402. doi:10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.07.005. PMID 16962184.

Bibliography

[edit]- Latchman, David S. (2005). Gene regulation: a eukaryotic perspective. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-36510-9.

External links

[edit]- Plant Transcription Factor Database and Plant Transcriptional Regulation Data and Analysis Platform

- Regulation of Gene Expression (MeSH) at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ChIPBase An open database for decoding the transcriptional regulatory networks of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes from ChIP-seq data.