Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

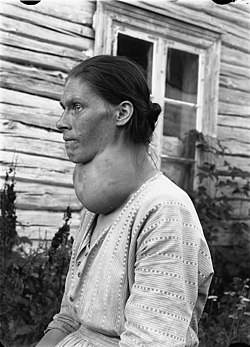

Goitre

View on Wikipedia

| Goitre | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Goiter |

| |

| Diffuse hyperplasia of the thyroid | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Causes | Iodine deficiency, autoimmune disease, tumors, cyanide poisoning |

A goitre (British English), or goiter (American English), is a swelling in the neck resulting from an enlarged thyroid gland.[1][2] A goitre can be associated with a thyroid that is not functioning properly.

Worldwide, over 90% of goitre cases are caused by iodine deficiency.[3] The term is from the Latin gutturia, meaning throat. Most goitres are not cancerous (benign), though they may be potentially harmful.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]A goitre can present as a palpable or visible enlargement of the thyroid gland at the base of the neck. A goitre, if associated with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, may be present with symptoms of the underlying disorder. For hyperthyroidism, the most common symptoms are associated with adrenergic stimulation: tachycardia (increased heart rate), palpitations, nervousness, tremor, increased blood pressure and heat intolerance. Clinical manifestations are often related to hypermetabolism (increased metabolism), excessive thyroid hormone, an increase in oxygen consumption, metabolic changes in protein metabolism, immunologic stimulation of diffuse goitre, and ocular changes (exophthalmos).[4] Hypothyroid people commonly have poor appetite, cold intolerance, constipation, lethargy and may undergo weight gain. However, these symptoms are often non-specific and make diagnosis difficult.[citation needed]

According to the WHO classification of goitre by palpation, the severity of goitre is currently graded as grade 0, grade 1, grade 2.[5]

-

Goitre Class II, WHO grade 2

-

Goitre Class III, WHO grade 2

Causes

[edit]Worldwide, the most common cause for goitre is iodine deficiency, commonly seen in countries that scarcely use iodized salt. Selenium deficiency is also considered a contributing factor. In countries that use iodized salt, Hashimoto's thyroiditis is the most common cause.[6] Goitre can also result from cyanide poisoning, which is particularly common in tropical countries where people eat the cyanide-rich cassava root as the staple food.[7]

| Cause | Pathophysiology | Resultant thyroid activity | Growth pattern | Treatment | Incidence and prevalence | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine deficiency | Hyperplasia of thyroid to compensate for decreased efficacy | Can cause hypothyroidism | Diffuse | Iodine | Constitutes over 90% cases of goitre worldwide[3] | Increased size of thyroid may be permanent if untreated for around five years |

| Congenital hypothyroidism | Inborn errors of thyroid hormone synthesis | Hypothyroidism | ||||

| Goitrogen ingestion | ||||||

| Adverse drug reactions | ||||||

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | Autoimmune disease in which the thyroid gland is gradually destroyed. Infiltration of lymphocytes. | Hypothyroidism | Diffuse and lobulated[8] | Thyroid hormone replacement | Prevalence: 1 to 1.5 in a 1000 | Remission with treatment |

| Pituitary disease | Hypersecretion of thyroid stimulating hormone, almost always by a pituitary adenoma[9] | Diffuse | Pituitary surgery | Very rare[9] | ||

| Graves' disease—also called Basedow syndrome | Autoantibodies (TSHR-Ab) that activate the TSH-receptor (TSHR) | Hyperthyroidism | Diffuse | Antithyroid agents, radioiodine, surgery | Will develop in about 0.5% of males and 3% of females | Remission with treatment, but still lower quality of life for 14 to 21 years after treatment, with lower mood and lower vitality, regardless of the choice of treatment[10] |

| Thyroiditis | Acute or chronic inflammation | Can be hyperthyroidism initially, but progress to hypothyroidism | ||||

| Thyroid cancer | Usually uninodular | Overall relative 5-year survival rate of 85% for females and 74% for males[11] | ||||

| Benign thyroid neoplasms | Usually hyperthyroidism | Usually uninodular | Mostly harmless[12] | |||

| Thyroid hormone insensitivity | Secretional hyperthyroidism, Symptomatic hypothyroidism |

Diffuse |

Diagnosis

[edit]

Goitre may be diagnosed via a thyroid function test in an individual suspected of having it.[13]

Types

[edit]A goitre may be classified either as nodular or diffuse. Nodular goitres are either of one nodule (uninodular) or of multiple nodules (multinodular).[14] Multinodular goiter (MNG) is the most common disorder of the thyroid gland.[15]

- Growth pattern

- Uninodular goitre: one thyroid nodule; can be either inactive, or active (toxic) – autonomously producing thyroid hormone.

- Multinodular goitre: multiple nodules;[16] can likewise be inactive or toxic, the latter is called toxic multinodular goitre and associated with hyperthyroidism. These nodules grow up at varying rates and secrete thyroid hormone autonomously, thereby suppressing TSH-dependent growth and function in the rest of gland. Inactive nodules in the same goitre can be malignant.[17] Thyroid cancer is identified in 13.7% of the patients operated for multinodular goitre.[18]

- Diffuse goitre: the whole thyroid appearing to be enlarged due to hyperplasia.

- Size

Treatment

[edit]Goitre is treated according to the cause. If the thyroid gland is producing an excess of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4), radioactive iodine is given to the patient to shrink the gland. If goitre is caused by iodine deficiency, small doses of iodide in the form of Lugol's iodine or KI solution are given. If the goitre is associated with an underactive thyroid, thyroid supplements are used as treatment. Sometimes a partial or complete thyroidectomy is required.[19]

Medical and scientific developments

[edit]The discovery of iodine's importance in thyroid function and its role in preventing goiter marked a significant medical breakthrough. The introduction of iodized salt in the early 20th century became a key public health initiative, effectively reducing the prevalence of goiter in previously affected regions. This measure was one of the earliest and most successful examples of mass preventive health campaigns.[20]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Goitre is more common among women, but this includes the many types of goitre caused by autoimmune problems, and not only those caused by simple lack of iodine.[22]

Iodine mainly accumulates in the sea and in the topsoil. Before iodine enrichment programs, goiters were common in areas with repeated flooding or glacial activities, which erodes the topsoil. It is endemic in populations where the intake of iodine is less than 10 μg per day.[23]

Examples of such regions include the alpine regions of Southern Europe (such as Switzerland), the Himalayans, the Great Lakes basin, etc. As reported in 1923, all the domestic animals have goiter in some of the glacial valleys of Southern Alaska. It was so severe in Pemberton Meadows that it was difficult to raise young animals there.[24]

History

[edit]

Chinese physicians of the Tang dynasty (618–907) were the first to successfully treat patients with goitre by using the iodine-rich thyroid gland of animals such as sheep and pigs—in raw, pill, or powdered form.[25] This was outlined in Zhen Quan's (d. 643 AD) book, as well as several others.[25] One Chinese book, The Pharmacopoeia of the Heavenly Husbandman, asserted that iodine-rich sargassum was used to treat goitre patients by the 1st century BC, but this book was written much later.[25]

In the 12th century, Zayn al-Din al-Jurjani, a Persian physician, provided the first description of Graves' disease after noting the association of goitre and a displacement of the eye known as exophthalmos in his Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm, the major medical dictionary of its time.[26][27] The disease was later named after Irish doctor Robert James Graves, who described a case of goitre with exophthalmos in 1835. The German Karl Adolph von Basedow also independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840, while earlier reports of the disease were also published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajani and Antonio Giuseppe Testa, in 1802 and 1810 respectively,[28] and by the English physician Caleb Hillier Parry (a friend of Edward Jenner) in the late 18th century.[29]

Paracelsus (1493–1541) was the first person to propose a relationship between goitre and minerals (particularly lead) in drinking water.[30] Iodine was later discovered by Bernard Courtois in 1811 from seaweed ash.[31]

Goitre was previously common in many areas that were deficient in iodine in the soil. For example, in the English Midlands, the condition was known as Derbyshire Neck. In the United States, goitre was found in the Appalachian,[32][33] Great Lakes, Midwest, and Intermountain regions. The condition is now practically absent in affluent nations, where table salt is supplemented with iodine. However, it is still prevalent in India, China,[34] Central Asia, and Central Africa.

Goitre had been prevalent in the alpine countries for a long time. Switzerland reduced the condition by introducing iodized salt in 1922. The Bavarian tracht in the Miesbach and Salzburg regions, which appeared in the 19th century, includes a choker, dubbed Kropfband (struma band) which was used to hide either the goitre or the remnants of goitre surgery.[35]

In various regions around the world, particularly in mountainous areas, the prevalence of goiter was linked to iodine deficiency in the diet. For example, the Alps, the Himalayas, and the Andes had high rates of goiter due to the iodine-poor soil. In these regions, iodine deficiency led to widespread hormonal imbalances, particularly affecting thyroid function.[36]

Society and culture

[edit]In the 1920s wearing bottles of iodine around the neck was believed to prevent goitre.[37]

Notable cases

[edit]- Former U.S. President George H. W. Bush and his wife Barbara Bush were both diagnosed with Graves' disease and goitres, within two years of each other. The disease caused hyperthyroidism and cardiac dysrhythmia.[38][39] Scientists said that, absent an environmental cause, the odds of both a husband and wife having Graves' disease might be 1 in 100,000 or as low as 1 in 3,000,000.[40]

Heraldry

[edit]The coat of arms and crest of Die Kröpfner, of Tyrol, showed a man "afflicted with a large goitre", an apparent pun on the German for the word ("Kropf").[41]

Social Impacts

[edit]In some historical contexts, goiters were so prevalent that they became normalized within the culture. For instance, in certain Alpine regions, large goiters were sometimes considered a sign of beauty. Conversely, in other areas, individuals with goiters faced social stigma, which could lead to marginalization and discrimination.[42]

See also

[edit]- David Marine conducted substantial research on the treatment of goitre with iodine.

- Endemic goitre

- Struma ovarii—a kind of teratoma

- Thyroid hormone receptor

References

[edit]- ^ "Thyroid Nodules and Swellings". British Thyroid Foundation. 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Goitre - NHS Choices". NHS Choices. 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b Hörmann R (2005). Schilddrüsenkrankheiten Leitfaden für Praxis und Klinik (4., aktualisierte und erw. Aufl ed.). Berlin. pp. 15–37. ISBN 3-936072-27-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Porth, Carol Mattson; Gaspard, Kathryn J; Noble, Kim A (2011). Essentials of Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-58255-724-3.[page needed]

- ^ Organization, World Health (2014). Goitre as a determinant of the prevalence and severity of iodine deficiency disorders in populations. World Health Organization. hdl:10665/133706.

- ^ Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ "Toxicological Profile For Cyanide" (PDF). Atsdr.cdc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2004. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Babademez MA, Tuncay KS, Zaim M, Acar B, Karaşen RM (November 2010). "Hashimoto thyroiditis and thyroid gland anomalies". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 21 (6): 1807–9. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f43e32. PMID 21119426.

- ^ a b Thyrotropin (TSH)-secreting pituitary adenomas. By Roy E Weiss and Samuel Refetoff. Last literature review version 19.1: January 2011. This topic last updated: 2 July 2009

- ^ Abraham-Nordling M, Törring O, Hamberger B, Lundell G, Tallstedt L, Calissendorff J, Wallin G (November 2005). "Graves' disease: a long-term quality-of-life follow up of patients randomized to treatment with antithyroid drugs, radioiodine, or surgery". Thyroid. 15 (11): 1279–86. doi:10.1089/thy.2005.15.1279. PMID 16356093.

- ^ Numbers from EUROCARE, from Page 10 in: Grünwald F, Biersack HJ (2005). Thyroid cancer. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-22309-2.

- ^ Bukvic BR, Zivaljevic VR, Sipetic SB, Diklic AD, Tausanovic KM, Paunovic IR (August 2014). "Improvement of quality of life in patients with benign goiter after surgical treatment". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 399 (6): 755–64. doi:10.1007/s00423-014-1221-7. PMID 25002182.

- ^ "Goitre". nhs.uk. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Chernock, Rebecca; Williams, Michelle D. (2021). "Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands". Gnepp's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. pp. 606–688. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-53114-6.00007-9. ISBN 978-0-323-53114-6.

- ^ Medeiros-Neto, Geraldo (2000). "Multinodular Goiter". Endotext. MDText.com, Inc. PMID 25905424.

- ^ Frilling A, Liu C, Weber F (2004). "Benign multinodular goiter". Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 93 (4): 278–81. doi:10.1177/145749690409300405. PMID 15658668.

- ^ "Toxic multinodular goitre - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com.

- ^ Gandolfi PP, Frisina A, Raffa M, Renda F, Rocchetti O, Ruggeri C, Tombolini A (August 2004). "The incidence of thyroid carcinoma in multinodular goiter: retrospective analysis". Acta Bio-Medica. 75 (2): 114–7. PMID 15481700.

- ^ "Goiter – Simple". The New York Times.

- ^ Hetzel, Basil S. (1993), "The Iodine Deficiency Disorders", Iodine Deficiency in Europe, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 25–31, doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1245-9_3, ISBN 978-1-4899-1247-3, retrieved 6 August 2024

- ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

- ^ 1

- ^ Goitre as a determinant of the prevalence and severity of iodine deficiency disorders in populations, World Health Organization - 2014

- ^ Kimball, O. P. (February 1923). "The Prevention of Simple Goiter". American Journal of Public Health. 13 (2): 81–87. doi:10.2105/ajph.13.2.81-a. PMC 1354367. PMID 18010882.

- ^ a b c Temple R (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc. pp. 134–5. ISBN 0-671-62028-2.

- ^ Basedow's syndrome or disease at Whonamedit? – the history and naming of the disease

- ^ Ljunggren JG (August 1983). "[Who was the man behind the syndrome: Ismail al-Jurjani, Testa, Flagani, Parry, Graves or Basedow? Use the term hyperthyreosis instead]". Läkartidningen. 80 (32–33): 2902. PMID 6355710.

- ^ Giuseppe Flajani at Whonamedit?

- ^ Hull G (June 1998). "Caleb Hillier Parry 1755-1822: a notable provincial physician". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 91 (6): 335–8. doi:10.1177/014107689809100618. PMC 1296785. PMID 9771526.

- ^ "Paracelsus" Britannica

- ^ "VI. Some experiments and observations on a new substance which becomes a violet coloured gas by heat". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 104: 74–93. 31 December 1814. doi:10.1098/rstl.1814.0007.

- ^ "Iodine Deficiency". Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Dorothy R. (1977). "Kentucky Appalachian Goiter Without Iodine Deficiency". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 131 (8): 866–869. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120210044010. PMID 888801.

- ^ "In Raising the World's I.Q., the Secret's in the Salt", article by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., 16 December 2006, The New York Times

- ^ Wissen, Planet (16 March 2017). "Planet Wissen".

- ^ Dunn, John T.; Delange, Francois (June 2001). "Damaged Reproduction: The Most Important Consequence of Iodine Deficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 86 (6): 2360–2363. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.6.7611. PMID 11397823.

- ^ "ARCHIVED – Why take iodine?". Nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. 30 September 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Lahita RG, Yalof I (20 July 2004). Women and Autoimmune Disease. HarperCollins. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-06-008149-2.

- ^ Altman LK (14 September 1991). "A White House Puzzle: Immunity Ailments". The New York Times.

Doctors Say Bush Is in Good Health

- ^ Altman LK (28 May 1991). "The Doctor's World; A White House Puzzle: Immunity Ailments". The New York Times.

- ^ Fox-Davies AC (1904). The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopædia of Armory. New York and London: Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 413.

- ^ Norling, Bernard (October 1977). "Plagues and Peoples - William H. McNeill: Plagues and Peoples. (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press, Doubleday, 1976. Pp. 369. $10.00.)". The Review of Politics. 39 (4): 557–560. doi:10.1017/s0034670500025043.

External links

[edit]Goitre

View on GrokipediaClinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

A goitre primarily manifests as an enlargement of the thyroid gland, appearing as a swelling at the base of the neck that can range from subtle and barely noticeable to a pronounced mass causing cosmetic concerns.[4][3] In many cases, individuals experience no symptoms beyond this visible or palpable swelling, with the goitre often discovered incidentally during routine physical examinations or imaging for unrelated issues.[4][1] When the goitre grows larger, it may exert pressure on surrounding structures, leading to compressive symptoms such as difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), a sensation of fullness or tightness in the neck, hoarseness, persistent cough, or noisy breathing.[5][1] In severe cases, significant enlargement can cause dyspnea, particularly during exertion, or even choking sensations due to airway compression.[4][3] Neck discomfort or pressure is also common, though most goitres remain painless unless associated with inflammation.[5][1] Goitres linked to thyroid hormone imbalances, such as toxic multinodular goitre, may present with systemic symptoms of hyperthyroidism including rapid heartbeat, unintended weight loss, heat intolerance, tremors, and increased sweating, which arise directly from the gland's overactivity amid its enlargement.[4][3] Conversely, goitres associated with hypothyroidism might involve fatigue, weight gain, and cold sensitivity, though these are secondary to the underlying dysfunction rather than the swelling itself.[4] The presentation can progress from an asymptomatic simple enlargement to more complicated forms, with rapid growth potentially indicating hemorrhage or inflammation leading to acute pain, as seen in rare cases of thyroiditis.[1][3] Substernal extension of the goitre may further complicate symptoms by causing facial flushing or worsened dyspnea upon arm elevation.[1]Physical Examination

The physical examination of a goiter begins with visual inspection of the neck, typically performed with the patient seated and the head slightly extended to optimize lighting on the anterior neck. The examiner observes for any visible swelling or asymmetry at the base of the neck, noting whether the enlargement moves upward with swallowing, which confirms its thyroid origin.[6] Prominent vascular pulsations may also be visible in cases of hypervascularity.[6] Palpation is the cornerstone of thyroid assessment, conducted with the examiner positioned behind or to the side of the patient to facilitate bimanual technique. The thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and sternal notch serve as key landmarks; the examiner gently places fingers along the trachea to palpate the isthmus and lobes, avoiding compression of the sternocleidomastoid muscles. To evaluate size, the normal thyroid lobes are approximately 7-10 grams each, and enlargement is gauged by the extent of palpable tissue extending beyond these bounds. Consistency is assessed as soft (common in diffuse goiters like those from iodine deficiency), firm (as in autoimmune thyroiditis), or nodular (indicating multinodular goiter); tenderness suggests inflammation, hemorrhage, or infection. Mobility is tested by having the patient swallow a sip of water, observing if the gland glides smoothly with the trachea—restricted movement may indicate adhesions from malignancy or fibrosis. The lower border is palpated to detect substernal extension; if not reachable, Pemberton's sign is elicited by raising the patient's arms overhead for one minute to provoke symptoms of thoracic inlet compression, such as facial flushing or dyspnea.[1][6][1] Auscultation follows palpation, using a stethoscope placed over the thyroid lobes to detect a bruit—a continuous whooshing sound signifying increased vascularity, often heard in hyperthyroid states like Graves' disease due to arteriovenous shunting. A palpable thrill may accompany louder bruits.[1][6] Thyroid enlargement is graded using the World Health Organization (WHO) system to standardize assessment: Grade 0 indicates no palpable or visible goiter; Grade 1 denotes a palpable gland not visible with the neck in normal position; and Grade 2 describes a goiter visible when the neck is in the normal position. This palpation-based grading helps quantify prevalence in endemic areas but may underestimate small or substernal goiters.[7][8] Associated features are evaluated concurrently: cervical lymphadenopathy is palpated in the anterior and posterior triangles, as enlarged nodes may signal thyroid malignancy or metastasis. In suspected Graves' disease, eye signs such as exophthalmos, lid lag, or periorbital edema are inspected for proptosis. Tracheal deviation is assessed by midline palpation of the trachea; lateral displacement suggests significant compression from a large goiter.[1][6][1] Differentiation between diffuse and nodular enlargement relies on palpation findings: a diffuse goiter presents as uniform, symmetrical swelling without discrete lumps, often seen in iodine deficiency or Hashimoto's thyroiditis, whereas nodular goiter features one or more firm, distinct masses that may be solitary or multiple, warranting further evaluation for autonomy or neoplasia.[1][6]Pathophysiology

Causes

Goitre, or thyroid enlargement, arises from various etiological factors that disrupt normal thyroid function or structure, leading to compensatory growth of the gland. The most common global cause is iodine deficiency, which impairs thyroid hormone synthesis and triggers increased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion from the pituitary gland, resulting in follicular cell hyperplasia and gland enlargement.[1] This mechanism is particularly prevalent in regions with low soil iodine content, where dietary intake is insufficient, affecting an estimated 2.2 billion people worldwide.[9] Endemic goitre refers to thyroid enlargement occurring in populations where prevalence exceeds 10%, primarily due to chronic iodine deficiency in iodine-poor geographic areas, often exacerbated by goitrogenic factors in local diets or water.[10] In contrast, sporadic goitre develops in iodine-sufficient regions and is typically linked to non-environmental triggers, such as genetic predispositions or isolated physiological demands, though it shares similar hyperplastic pathways.[11] Autoimmune disorders are significant causes of goitre in iodine-replete settings. Hashimoto's thyroiditis, an autoimmune condition characterized by lymphocytic infiltration and antibody-mediated destruction of thyroid tissue, leads to hypothyroidism and subsequent goitrous enlargement as the gland attempts to compensate for reduced hormone production.[12] Conversely, Graves' disease, another autoimmune thyroiditis, causes hyperthyroidism through TSH receptor-stimulating antibodies, promoting diffuse thyroid hyperplasia and goitre formation.[13] Certain pharmacological agents interfere with thyroid hormone synthesis or release, inducing goitre. Lithium, commonly used in bipolar disorder treatment, inhibits thyroid hormone release and iodide uptake, leading to elevated TSH levels and glandular hypertrophy in up to 40% of long-term users.[1] Amiodarone, an antiarrhythmic drug rich in iodine, can paradoxically disrupt thyroid function by causing either hypothyroidism through Wolff-Chaikoff effect inhibition or destructive thyroiditis, both resulting in goitre.[14] Physiological states with heightened thyroid hormone demands can cause transient goitre due to temporary hyperplasia. During puberty, pregnancy, and menopause, increased estrogen levels enhance TSH sensitivity and thyroid-binding globulin, elevating hormone requirements and prompting gland enlargement, particularly in women.[15] In pregnancy, this goitrogenesis is driven by higher metabolic needs and hCG-mediated TSH suppression, often resolving postpartum.[16] Rare causes include infectious, radiation-induced, and infiltrative processes. Subacute thyroiditis, often viral in origin, leads to painful goitre through granulomatous inflammation and follicular disruption, causing transient hyperthyroidism followed by hypothyroidism.[17] External radiation exposure, such as from medical treatments or environmental accidents, damages thyroid follicles and induces fibrosis or nodular growth, increasing goitre risk dose-dependently.[1] Infiltrative diseases like amyloidosis deposit amyloid proteins in the thyroid interstitium, causing compressive enlargement and functional impairment.[17]Types

Goitres are classified based on their structural characteristics, functional status, etiology, and specific morphological features. Structurally, they can be diffuse or nodular. A diffuse goitre involves uniform enlargement of the entire thyroid gland, resulting in a smooth, symmetric swelling without discrete lumps.[1] In contrast, a nodular goitre features one or more focal nodules; these may be solitary (uninodular) or multiple (multinodular), often developing from compensatory hyperplasia in response to chronic stimulation.[18] Multinodular goitres are common in long-standing cases and can lead to irregular gland contours.[1] Functionally, goitres are categorized as simple (euthyroid), toxic (hyperfunctioning), or hypofunctioning. Simple goitres maintain normal thyroid hormone levels (euthyroidism) despite enlargement, typically arising from physiological adaptations or mild deficiencies without disrupting hormone synthesis.[18] Toxic goitres, however, are hyperfunctioning, producing excess thyroid hormones and causing thyrotoxicosis; examples include toxic multinodular goitre, where autonomous nodules overproduce hormones, or toxic diffuse goitre as seen in Graves' disease.[1] Hypofunctioning goitres are associated with reduced hormone output, leading to hypothyroidism, often due to autoimmune destruction or biosynthetic defects in the gland.[18] Etiologically, goitres are distinguished as endemic or sporadic. Endemic goitre occurs in populations where iodine deficiency affects more than 10% of individuals, leading to widespread thyroid enlargement as a compensatory response to insufficient iodine for hormone production.[1] Sporadic goitre, conversely, arises in iodine-sufficient areas and affects individuals idiosyncratically, often linked to autoimmune conditions, medications, or isolated genetic factors rather than environmental deficiencies.[19] Congenital goitre manifests at birth and results from fetal exposure to iodine deficiency during gestation or intrinsic genetic defects impairing thyroid hormone synthesis, such as mutations in genes encoding the sodium-iodide symporter or thyroid peroxidase.[20] These can present as diffuse enlargement and may be associated with hypothyroidism if untreated.[21] Certain goitres exhibit specific morphological variants, including cystic or hemorrhagic types. Cystic goitres contain fluid-filled sacs within nodules, which may arise from degeneration of follicular tissue.[18] Hemorrhagic goitres involve bleeding into nodules or the gland parenchyma, potentially causing sudden pain and rapid enlargement due to hematoma formation.[18] The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a classification framework emphasizing physiological, non-toxic, and toxic categories, particularly for multinodular forms. Physiological goitres represent adaptive enlargements, such as during puberty or pregnancy, without pathological implications.[1] Non-toxic multinodular goitres are euthyroid or hypothyroid enlargements with multiple nodules but no hyperfunction.[1] Toxic multinodular goitres, in contrast, feature hyperfunctioning nodules leading to thyrotoxicosis.[1] This system aids in distinguishing benign adaptive changes from those requiring intervention.[1]Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnosis of goiter typically begins with laboratory assessments to evaluate thyroid function and potential underlying autoimmune processes. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels are measured as the initial test, with subnormal TSH prompting further evaluation for hyperthyroidism and elevated TSH indicating hypothyroidism. Free thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) levels are then assessed to confirm the functional status of the thyroid gland. Additionally, thyroid autoantibodies such as anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies are tested to identify autoimmune etiologies like Hashimoto's thyroiditis, which is a common cause of goitrous hypothyroidism.[22][23] Ultrasound serves as the first-line imaging modality for characterizing goiter, providing detailed assessment of thyroid size, echotexture, nodularity, vascularity, and the presence of calcifications. High-resolution ultrasound can detect nodules as small as 1-2 mm and is essential for risk stratification using sonographic patterns, such as solid hypoechoic composition or microcalcifications, which indicate higher malignancy risk. For nodules greater than 1 cm with suspicious features, ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is performed to obtain cytology samples, enabling evaluation for malignancy. FNA involves inserting a thin needle into the nodule under real-time ultrasound guidance to minimize complications and improve accuracy.[23][24] Cytological results from FNA are reported using the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology, a standardized six-category framework that correlates with the risk of malignancy. The categories include: nondiagnostic (risk 1-4%), benign (0-3%), atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance (5-15%), follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm (15-30%), suspicious for malignancy (60-75%), and malignant (97-99%). This system facilitates consistent communication between pathologists and clinicians, guiding decisions on whether to pursue diagnostic lobectomy or molecular testing for indeterminate results. Thyroid scintigraphy, often using technetium-99m pertechnetate or iodine-123, is employed when TSH is subnormal to differentiate hyperfunctioning ("hot") nodules, which are typically benign, from nonfunctioning ("cold") nodules that may harbor malignancy or represent hypofunction. In multinodular goiter, scintigraphy helps identify autonomously functioning areas contributing to hyperthyroidism. The procedure involves intravenous injection of the radiotracer followed by imaging to assess uptake and nodule functionality, providing functional rather than anatomical detail.[23][24] Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reserved for cases with suspected compressive symptoms or retrosternal extension, offering superior visualization of the goiter's relationship to surrounding structures like the trachea and esophagus. Contrast-enhanced CT is particularly useful for detecting substernal components and vascular involvement, while MRI provides better soft-tissue contrast without radiation exposure. These modalities are not routine but are indicated when ultrasound is inconclusive or symptoms such as dysphagia or dyspnea suggest extrinsic compression.[1][23]Classification and Staging

Goitre classification and staging involve multiple systems to assess severity, functional status, size, malignancy potential, and complications, guiding clinical management and surgical decisions. These systems interpret diagnostic findings, such as ultrasound and thyroid function tests, to stratify risk and prognosis without overlapping etiological typing. Nodular goitres are classified using the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS), particularly the American College of Radiology (ACR) TI-RADS, which evaluates ultrasound features to predict malignancy risk. The system assigns points based on five categories: composition (0-2 points), echogenicity (0-3 points), shape (0-3 points), margin (0-3 points), and echogenic foci (0-3 points), with total points determining the TI-RADS level. Nodules are categorized as TR1 (0 points, benign pattern, 0.3% malignancy risk), TR2 (2 points, not suspicious, 1.5% risk), TR3 (3 points, mildly suspicious, 4.8% risk), TR4 (4-6 points, moderately suspicious, 9.1% risk), and TR5 (≥7 points, highly suspicious, 35% risk). This scoring helps prioritize fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy for higher-risk nodules.[25]| Feature Category | Scoring (Points) |

|---|---|

| Composition | Cystic/spongiform: 0; Mixed: 1; Solid: 2 |

| Echogenicity | Anechoic: 0; Hyper- or isoechoic: 1; Hypoechoic: 2; Very hypoechoic: 3 |

| Shape | Wider-than-tall: 0; Taller-than-wide: 3 |

| Margin | Smooth or ill-defined: 0; Lobulated/irregular: 2; Extrathyroidal extension: 3 |

| Echogenic Foci | None/comet-tail: 0; Macrocalcifications: 1; Peripheral: 2; Punctate: 3 |