Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

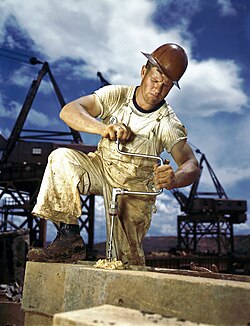

Hard hat

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

A hard hat is a type of helmet predominantly used in hazardous environments such as industrial or construction sites to protect the head from injury due to falling objects (such as tools and debris), impact with other objects, and electric shock, as well as from rain. Suspension bands inside the helmet spread the helmet's weight and the force of any impact over the top of the head. A suspension also provides space of approximately 30 mm (1.2 inches) between the helmet's shell and the wearer's head, so that if an object strikes the shell, the impact is less likely to be transmitted directly to the skull. Some helmet shells have a mid-line reinforcement ridge to improve impact resistance. The rock climbing helmet fulfills a very similar role in a different context and has a very similar design.

A bump cap is a lightweight hard hat using a simplified suspension or padding and a chin strap. Bump caps are used where there is a possibility of scraping or bumping one's head on equipment or structure projections but are not sufficient to absorb large impacts, such as that from a tool dropped from several stories.

History

[edit]

In the early years of the shipbuilding industry, workers covered their hats with pitch (tar) and set them in the sun to cure and harden, a common practice for dock workers in constant danger of being hit on the head by objects dropped from ship decks.

Management professor Peter Drucker credited writer Franz Kafka with developing the first civilian hard hat while employed at the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia (1912), but this information is not supported by any document from his employer.[1]

In the United States, the E.D. Bullard Company was a mining equipment firm in California created by Edward Dickinson Bullard in 1898, a veteran of the industrial safety business for 20 years. The company sold protective hats made of leather. His son, E. W. Bullard, returned home from World War I with a steel helmet that provided him with ideas to improve industrial safety.[2] In 1919 Bullard patented a "Hard-Boiled hat" made of steamed canvas, glue and black paint.[3] That same year, the U.S. Navy commissioned Bullard to create a shipyard protective cap that began the widespread use of hard hats. Not long after, Bullard developed an internal suspension to provide a more effective hat. These early designs bore a resemblance to the steel M1917 "Brodie" military helmet that served as their inspiration.

MSA introduced the new non-conductive thermoplastic, reinforced Bakelite-based "Skullguard" Helmet in 1930. Able to withstand high temperatures and radiant heat loads in the metals industry up to 350 °F (177 °C) without burning the wearer, it was also safe around high-voltage electricity. Bakelite was used to provide protection rigid enough to withstand hard sudden impacts within a high-heat environment but still be light enough for practical use. Made of a Bakelite resin reinforced with wire screen and linen, the Skullgard Helmet is still manufactured in nearly two dozen models in 2021. MSA also produced a low-crown version for coal miners known as Comfo-Cap Headgear, likewise offered with fittings for a headlamp and battery.

On the Hoover Dam project in 1931, hard hat use was mandated by Six Companies, Inc. In 1933, construction began on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco California. Construction workers were required to wear hard hats, by order of Joseph Strauss, project chief engineer. Strauss strove to create a safe workplace; hence, he installed safety nets and required hard hats to be worn while on the job site. Strauss also asked Bullard to create a hard hat to protect workers who performed sandblasting. Bullard produced a design that covered the worker's face, provided a window for vision and a supply of fresh air via a hose connected to an air compressor. The MSA Skullgard was the best, but quite expensive. Many hard hats were made of cheaper steel.

Lighter affordable aluminum became popular for hard hats around 1938, except for electrical applications. Fiberglass came into use in the 1940s.

Injection-molded thermoplastics appeared in the 1950s, and began to dominate in the 1960s. Easily shaped with heat, it is cost-effective to manufacture. In 1952, MSA offered the Shockgard Helmet to protect linemen from electrical shock of up to 10,000 volts. In 1961, MSA released the Topgard Helmet, the first polycarbonate hard hat. 1962 brought the V-Gard Helmet, which today is the most widely used hard hat in the United States.[citation needed] Today, most hard hats are made from high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or advanced engineering resins, such as Ultem.

In 1997, ANSI allowed the development of a ventilated hard hat to keep wearers cooler. Accessories such as face shields, sun visors, earmuffs, and perspiration-absorbing lining cloths could also be used; today, attachments include radios, walkie-talkies, pagers, and cameras.[citation needed]

Design

[edit]

Because hard hats are intended to protect the wearer's head from impacts, hats are made from durable materials, originally from metal, then Bakelite composite, fiberglass, and most-commonly (from the 1950s onward) molded thermoplastic.

Some contemporary cap-style hard hats feature a rolled edge that acts as a rain gutter to channel rainwater to the front, allowing water to drain off the bill, instead of running down the wearer's neck. A wide-brimmed cowboy hat-style hard hat is made,[4] although some organizations disallow their use.

Organizations issuing hard hats often include their name, logo, or some other message (as for a ceremonial corner stone laying) on the front.

Accessories

[edit]Hard hats may also be fitted with:

- A visor, as in a welding helmet, or safety visor.

- An extra-wide brim attachment for additional shade.

- Ear protectors.

- Mirrors for increased rear field-of-view.

- A small device that is used to mount a headlamp or flashlight to a hard hat. The mounting device frees hands to continue working rather than having to hold a flashlight.

- A chinstrap to keep the helmet from falling off if the wearer leans over.

- Thick insulating side pads to keep sides of the head warm. Examples are seen in Ice Road Truckers.

- Silicone bands stretched around the brim for color worker ID and Hi Viz night retro-reflectivity.

Colors and identification

[edit]

Hard hat colors can signify different roles on construction sites. These color designations vary from company to company and worksite to worksite. Government agencies such as the United States Navy and DOT have their own hard hat color scheme that may apply to subcontractors. On very large projects involving a number of companies, employees of the same company may wear the same color hat.

Stickers

[edit]Stickers, labels and markers are used to mark hard hats so that important information can be shared. As some paints or permanent markers can degrade the plastic in hard hats, adhesive labels or tape are often used instead. Stickers with company logos, and those that indicate a worker's training, qualifications, or security level, are also common. Many companies provide ready-made stickers to indicate that a worker has been trained in electrical, confined space, or excavation trench safety, as well as operation of specialized equipment. Environmental monitors often make stickers to indicate that the worker has been educated on the risk of unexploded ordnance or the archaeological/biological sensitivity of a given area. Unions may offer hard hat stickers to their members to promote the union, encourage safety, and commemorate significant milestones.

A hard hat also provides workers with a distinctive profile, readily identifiable even in peripheral vision, for safety around equipment or traffic. Reflective tape can increase visibility both day and night.

Standards

[edit]

OSHA regulation 1910.135 states that the employer shall ensure that each affected employee wears a protective helmet when working in areas where there is a potential for injury to the head from falling objects. Additionally, the employer shall ensure that a protective helmet designed to reduce electrical shock hazard is worn by each such affected employee when near exposed electrical conductors which could contact the head.[5]

The OSHA regulation does not specifically cover any criteria for the protective helmets, instead OSHA requires that protective helmets comply with ANSI/ISEA Z89.1-2014 – American National Standard for Industrial Head Protection.

Each hard hat is specified by both Type and Class. Types include:

- ANSI Type I / CSA Type 1 hard hats meet stringent vertical impact and penetration requirements.

- ANSI Type II / CSA Type 2 hard hats meet both vertical and lateral impact and penetration requirements and have a foam inner liner made of expanded polystyrene (EPS).

Classes:

- Class E (Electrical) provides dielectric protection up to 20,000 volts.

- Class G (General) provides dielectric protection up to 2,200 volts.

- Class C (Conductive) provides no dielectric protection.

A hard hat is specified by both Type and Class; for example: Type I Class G.

ANSI standards for hard hats set combustibility or flammability criteria. ANSI Z89 standard was significantly revised in 1986, 1997 and 2003. The current American standard for hard hats is ISEA Z89.1-2009, by the International Safety Equipment Association that took over publication of the Z89 standard from ANSI. The ISO standard for industrial protective headgear is ISO 3873, first published in 1977.

In the UK, the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Regulations 1992 specifies that hard hats are a component of PPE and, by law, all those working on construction sites or within hazardous environments are required to wear hard hats.

In Europe all hard hats must have a manufacturer set lifespan, this can be determined from the expiry date or a set period from the manufacture date, which is either stuck to the inside or embossed in the hard hat's material.

Examples

[edit]-

Full-brimmed hard hat

-

Baseball cap style safety helmet with visor and chin strap

-

With headset

-

With a light mount

-

Shock-absorbing suspension system inside a typical hard hat

-

An example of an early leather hard hat.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Drucker, Peter. Managing in the Next Society. See: Franz Kafka, Amtliche Schriften. Eds. K. Hermsdorf & B. Wagner (2004) (Engl. transl.: The Office Writings. Eds. S. Corngold, J. Greenberg & B. Wagner. Transl. E. Patton with R. Hein (2008)); cf. H.-G. Koch & K. Wagenbach (eds.), Kafkas Fabriken (2002).

- ^ Kindy, David (2020-02-21). "The History of the Hard Hat". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2023-06-01. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ "Bullard Hard Boiled Miner's Helmet". National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on 2023-09-12. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ "Cowboy Hard Hat Inventor – Bret Atkins". Archived from the original on 2010-08-14. Retrieved 27 Sep 2010.

- ^ "OSHA". OSHA.gov. United States Department of Labor.

Hard hat

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

A hard hat is a rigid protective helmet designed to shield the wearer's head from impacts, falling or flying objects, electrical hazards, and other workplace dangers commonly encountered in construction, mining, and industrial settings.[3] As a form of personal protective equipment (PPE), it serves as the primary barrier against head injuries in environments where overhead risks are present.[4] The primary purposes of a hard hat include absorbing shock from blows to reduce the force transmitted to the head, distributing impact energy across the helmet's shell to prevent localized damage, resisting penetration by sharp or heavy objects, and providing insulation against electrical shocks and burns.[5] These functions are essential for protecting workers from common hazards such as debris falls or accidental contact with live wires, thereby minimizing the risk of traumatic brain injuries, skull fractures, or electrocution.[6] At its core, the basic mechanics of a hard hat rely on a suspension system that creates a small gap—typically 1 to 1.25 inches—between the rigid outer shell and the wearer's head, allowing the shell to absorb and dissipate impact energy without direct transmission to the skull.[4] This design ensures that the helmet deforms or flexes upon impact to cradle and protect the head, enhancing overall safety in hazardous occupations. Originating as industrial safety gear to address the growing needs of early 20th-century workers in high-risk fields like construction and mining, hard hats have become a standard requirement under occupational safety regulations.[7]Types

Hard hats are classified primarily under the ANSI/ISEA Z89.1-2014 (R2019) standard, which defines two types based on impact protection and three classes based on electrical hazard resistance.[1] Type I hard hats provide protection against impacts to the top of the head, suitable for environments where falling objects strike from above, while Type II hard hats offer enhanced protection against lateral impacts to the top, sides, front, and back, making them ideal for higher-risk settings with multi-directional threats.[8] These types ensure the helmet's shell and suspension system absorb and distribute force to minimize injury.[1] The classes focus on dielectric properties for electrical safety. Class G (General) hard hats reduce exposure to low-voltage conductors, proof-tested at 2,200 volts phase-to-ground with a maximum leakage current of 3 milliamperes.[1] Class E (Electrical) hard hats provide higher protection against voltages up to 20,000 volts phase-to-ground, limited to 9 milliamperes leakage, and are designed for utility and electrical work near energized lines.[1] Class C (Conductive) hard hats offer no electrical insulation but prioritize ventilation and comfort for non-conductive environments like general construction without voltage risks.[1] Prior classifications under older ANSI Z89.1 versions, still referenced in some OSHA contexts, included Class A (equivalent to current Class G, up to 2,200 volts) and Class B (equivalent to Class E, up to 20,000 volts, often for welding and electrical tasks), along with Class C (no electrical protection).[9] Type B (now Class E) was particularly suited for utility line work involving higher voltages, distinguishing it from general use by its enhanced dielectric testing.[10] Specialized variants address niche hazards. Bump caps, unlike full hard hats, protect against minor bumps from fixed low-overhead objects like pipes in confined spaces but do not meet ANSI Z89.1 impact standards for falling objects and are prohibited where such risks exist per OSHA interpretations.[11] Proximity helmets, often Class E with integrated arc-rated face shields (meeting NFPA 70E for arc flash ratings up to 40 cal/cm²), are used by electrical workers near live equipment to guard against arc flash and proximity shocks. Selection of hard hat types and classes depends on a workplace hazard assessment under OSHA 29 CFR 1910.132, evaluating impact directions, electrical voltages present, and environmental factors to ensure appropriate protection without over-specification.| Class | Electrical Protection (Volts, Phase-to-Ground) | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| G (formerly A) | Up to 2,200 | General industrial, low-voltage |

| E (formerly B) | Up to 20,000 | Utilities, electrical work |

| C | None | Non-conductive environments |