Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

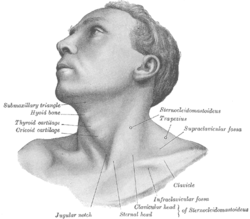

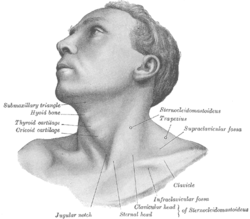

Torticollis

View on Wikipedia| Torticollis | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| |

| The muscles involved with torticollis | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Diagnostic method | Ultrasonography |

Torticollis, also known as wry neck, is an extremely painful, dystonic condition defined by an abnormal, asymmetrical head or neck position, which may be due to a variety of causes. The term torticollis is derived from Latin tortus 'twisted' and collum 'neck'.[1][2]

The most common case has no obvious cause, and the pain and difficulty in turning the head usually goes away after a few days, even without treatment in adults.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Torticollis is a fixed or dynamic tilt, rotation, with flexion or extension of the head and/or neck.

The type of torticollis can be described depending on the positions of the head and neck.[1][3][4]

- laterocollis: the head is tipped toward the shoulder

- rotational torticollis: the head rotates along the longitudinal axis towards the shoulder[5]

- anterocollis: forward flexion of the head and neck[6] and brings the chin towards the chest[5]

- retrocollis: hyperextension of head and neck backward[7] bringing the back of the head towards the back[5]

A combination of these movements may often be observed. Torticollis can be a disorder in itself as well as a symptom in other conditions.

Other signs and symptoms include:[8][9]

- Neck pain

- Occasional formation of a mass

- Thickened or tight sternocleidomastoid muscle

- Tenderness on the cervical spine

- Tremor in head

- Unequal shoulder heights

- Decreased neck movement

Causes

[edit]A multitude of conditions may lead to the development of torticollis including: muscular fibrosis, congenital spine abnormalities, or toxic or traumatic brain injury.[2] A rough categorization discerns between congenital torticollis and acquired torticollis.[10]

Other categories include:[11]

- Osseous

- Traumatic

- CNS/PNS

- Ocular

- Non-muscular soft tissue

- Spasmodic

- Drug induced

- Oral ties (lip and tongue ties)

Congenital muscular torticollis

[edit]Congenital muscular torticollis is the most common torticollis that is present at birth.[12] Congenital muscular torticollis is the third most common congenital musculoskeletal deformity in children.[13] The cause of congenital muscular torticollis is unclear. Birth trauma or intrauterine malposition is considered to be the cause of damage to the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the neck.[2] Other alterations to the muscle tissue arise from repetitive microtrauma within the womb or a sudden change in the calcium concentration in the body that causes a prolonged period of muscle contraction.[14]

Any of these mechanisms can result in a shortening or excessive contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which curtails its range of motion in both rotation and lateral bending. The head is typically tilted in lateral bending toward the affected muscle and rotated toward the opposite side. In other words, the head itself is tilted in the direction of the shortened muscle, with the chin tilted in the opposite direction.[11]

Congenital torticollis is presented at 1–4 weeks of age, and a hard mass usually develops. It is normally diagnosed using ultrasonography and a color histogram or clinically by evaluating the infant's passive cervical range of motion.[15]

Congenital torticollis constitutes the majority of cases seen in paediatric clinical practice.[11] The reported incidence of congenital torticollis is 0.3-2.0%.[16] Sometimes a mass, such as a sternocleidomastoid tumor, is noted in the affected muscle. Congenital Muscular Torticollis is also defined by a fibrosis contracture of the sternocleidomastoid muscle on one side of the neck.[13] Congenital torticollis may not resolve on its own, and can result in rare complications including plagiocephaly.[17] Secondary complications associated with Congenital Muscular Torticollis include visual dysfunctions, facial asymmetry, delayed development, cervical scoliosis, and vertebral wedge degeneration which will have a serious impact on the child's appearance and even mental health.[13]

Benign paroxysmal torticollis is a rare disorder affecting infants. Recurrent attacks may last up to a week. The condition improves by age 2. The cause is thought to be genetic.[18]

Acquired torticollis

[edit]Noncongenital muscular torticollis may result from muscle spasm, trauma, scarring or disease of cervical vertebrae, adenitis, tonsillitis, rheumatism, enlarged cervical glands, retropharyngeal abscess, or cerebellar tumors.[19] It may be spasmodic (clonic) or permanent (tonic). The latter type may be due to Pott's Disease (tuberculosis of the spine).[20]

- A self-limiting spontaneously occurring form of torticollis with one or more painful neck muscles is by far the most common ('stiff neck') and will pass spontaneously in 1–4 weeks. Usually the sternocleidomastoid muscle or the trapezius muscle is involved. Sometimes draughts, colds, or unusual postures are implicated; however, in many cases, no clear cause is found. These episodes are commonly seen by physicians.[citation needed]

Most commonly this self-limiting form relates to an untreated dental occlusal dysfunction, which is brought on by clenching and grinding the teeth during sleep. Once the occlusion is treated it will completely resolve. Treatment is accomplished with an occlusal appliance, and equilibration of the dentition.[citation needed]

- Tumors of the skull base (posterior fossa tumors) can compress the nerve supply to the neck and cause torticollis, and these problems must be treated surgically.

- Infections in the posterior pharynx can irritate the nerves supplying the neck muscles and cause torticollis, and these infections may be treated with antibiotics if they are not too severe, but could require surgical debridement in intractable cases.

- Ear infections and surgical removal of the adenoids can cause an entity known as Grisel's syndrome, a subluxation of the upper cervical joints, mostly the atlantoaxial joint, due to inflammatory laxity of the ligaments caused by an infection.[21]

- The use of certain drugs, such as antipsychotics, can cause torticollis.[22]

- Antiemetics - Neuroleptic Class - Phenothiazines

- There are many other rare causes of torticollis. A very rare cause of acquired torticollis is fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), the hallmark of which is malformed great toes.

Spasmodic torticollis

[edit]Torticollis with recurrent, but transient contraction of the muscles of the neck and especially of the sternocleidomastoid, is called spasmodic torticollis. Synonyms are "intermittent torticollis", "cervical dystonia" or "idiopathic cervical dystonia", depending on cause.[23]

Trochlear torticollis

[edit]Torticollis can be caused by damage to the trochlear nerve (fourth cranial nerve), which supplies the superior oblique muscle of the eye. The superior oblique muscle is involved in depression, abduction, and intorsion of the eye. When the trochlear nerve is damaged, the eye is extorted because the superior oblique is not functioning. The affected person will have vision problems unless they turn their head away from the side that is affected, causing intorsion of the eye and balancing out the extorsion of the eye. This can be diagnosed by the Bielschowsky test, also called the head-tilt test, where the head is turned to the affected side. A positive test occurs when the affected eye elevates, seeming to float up.[24]

Anatomy

[edit]The main job of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is to help move the head and neck by turning the head to one side and bending the neck forward.[25] The sternocleidomastoid muscle gets its blood from different arteries in the neck, which bring oxygen and nutrients to keep the muscle healthy. Torticollis can happen when there are issues with the sternocleidomastoid muscle, like if it's too short, causing the head and neck to be in an odd position.[25] Torticollis can also be caused by problems with bones, muscles, or the spine in the neck, leading to difficulty moving the head and neck normally.[25] Knowing about the sternocleidomastoid muscle and how it works is crucial for doctors to diagnose and treat torticollis correctly, so they can find and fix the problem causing it. Differences in how the sternocleidomastoid muscle is supplied with blood or nerves can affect how torticollis develops or how well treatments work, so it's important for doctors to consider these variations when planning treatment.[26] Having a good understanding of the neck's anatomy helps doctors accurately diagnose torticollis and choose the best treatments to help patients feel better.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle gets signals from nerves in the neck and head to contract and move properly. The underlying anatomical distortion causing torticollis is a shortened sternocleidomastoid muscle. This is the muscle of the neck that originates at the sternum and clavicle and inserts on the mastoid process of the temporal bone on the same side.[11] There are two sternocleidomastoid muscles in the human body and when they both contract, the neck is flexed. The main blood supply for these muscles come from the occipital artery, superior thyroid artery, transverse scapular artery and transverse cervical artery.[11] The main innervation to these muscles is from cranial nerve XI (the accessory nerve) but the second, third and fourth cervical nerves are also involved.[11] Pathologies in these blood and nerve supplies can lead to torticollis.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Evaluation of a child with torticollis begins with history taking to determine circumstances surrounding birth and any possibility of trauma or associated symptoms. Physical examination reveals decreased rotation and bending to the side opposite from the affected muscle. Some[who?] say that congenital cases more often involve the right side, but there is not complete agreement about this in published studies. Evaluation should include a thorough neurologic examination, and the possibility of associated conditions such as developmental dysplasia of the hip and clubfoot should be examined. Radiographs of the cervical spine should be obtained to rule out obvious bony abnormality, and MRI should be considered if there is concern about structural problems or other conditions.

Ultrasonography can be used to visualize muscle tissue, with a colour histogram generated to determine cross-sectional area and thickness of the muscle.[27]

Evaluation by an optometrist or an ophthalmologist should be considered in children to ensure that the torticollis is not caused by vision problems (IV cranial nerve palsy, nystagmus-associated "null position", etc.).

Differential diagnosis for torticollis includes[11][28]

- Cranial nerve IV palsy

- Spasmus nutans[29]

- Sandifer syndrome

- Myasthenia gravis

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak

Cervical dystonia appearing in adulthood has been believed to be idiopathic in nature, as specific imaging techniques most often find no specific cause.[30]

Treatment

[edit]Teaching people how to sit and stand properly can help reduce strain on the neck muscles and improve posture. Changing habits like bad posture or repetitive movements can help ease symptoms of torticollis.[26] Wearing a special collar can also support the neck and keep it in the right position during daily activities. Using electrical devices have also been shown to reduce pain, make muscles work better, and relax tight muscles.[31] Injecting a substance like Botox into overactive muscles can weaken them temporarily, allowing for better movement.[32] If other treatments don't work, surgery might be needed to fix the muscles or bones causing torticollis.

Physical therapy

[edit]Physical therapy is an option for treating torticollis in a non-invasive and cost-effective manner.[33] Physical therapy is seen as an early conservative intervention to minimize the intensity of the musculoskeletal disorder, leading to short durations of care as well as improved outcomes from treatment. The Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CMT CPG) reflects the recommendations and guidelines for physical therapists in diagnosing, treating and educating families of infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physical therapists that reported using the 2013 CMT CPG in their practices saw patient torticollis resolution in as little as 6-months increase from 42%-61%. As of currently, there is an updated 2024 CMT CMG from the American Physical Therapy Association.[34][35] In the children above 1 year of age, surgical release of the tight sternocleidomastoid muscle is indicated along with aggressive therapy and appropriate splinting. Occupational therapy rehabilitation in congenital muscular torticollis concentrates on observation, orthosis, gentle stretching, myofascial release techniques, parents' counseling-training, and home exercise program. While outpatient infant physiotherapy is effective, home therapy performed by a parent or guardian is just as effective in reversing the effects of congenital torticollis.[14] It is important for physical therapists to educate parents on the importance of their role in the treatment and to create a home treatment plan together with them for the best results for their child.

Five components have been recognized as the "first choice intervention" in PT for treatment of torticollis and include

- neck passive range of motion,

- neck and trunk active range of motion,

- development of symmetrical movement,

- environmental adaptations, and

- caregiver education

In therapy, parents or guardians should expect their child to be provided with these important components, explained in detail below.[36] Lateral neck flexion and overall range of motion can be regained quicker in newborns when parents conduct physical therapy exercises several times a day.[14]

Physical therapists should teach parents and guardians to perform the following exercises:[14]

- Stretching the neck and trunk muscles actively. Parents can help promote this stretching at home with infant positioning.[36] For example, prone positioning will encourage the child to lift their chin off the ground, thereby strengthening their bilateral neck and spine extensor muscles, and stretching their neck flexor muscles.[36] Active rotation exercises in supine, sitting or prone position by using toys, lights and sounds to attract infant's attention to turn neck and look toward the non-affected side.[36]

- Stretching the muscle in a prone position passively.[36] Passive stretching is manual, and does not include infant involvement. Two people can be involved in these stretches, one person stabilizing the infant while the other holds the head and slowly brings it through the available range of motion.[36] Passive stretching should not be painful to the child, and should be stopped if the child resists.[36] Also, discontinue the stretch if changes in breathing or circulation are seen or felt.[36]

- Stretching the muscle in a lateral position supported by a pillow (have infant lie on the side with the neck supported by pillow). Affected side should be against the pillow to deviate the neck towards the non-affected side.[citation needed]

- Environmental adaptations can control posture in strollers, car seats and swings (using U-shaped neck pillow or blankets to hold neck in neutral position)[citation needed]

- Passive cervical rotation (much like stretching when being supported by a pillow, have affected side down)[37]

- Position infant in the crib with affected side by the wall so they must turn to the non-affected side to face out[citation needed]

Physical therapists often encourage parents and caregivers of children with torticollis to modify the environment to improve neck movements and position. Modifications may include:

- Adding neck supports to the car seat to attain optimal neck alignment

- Reducing time spent in a single position

- Using toys to encourage the child to look in the direction of limited neck movement

- Alternating sides when bottle or breastfeeding[36]

- Encouraging prone playtime. Although the Back to Sleep campaign promotes infants sleeping on their backs to avoid sudden infant death syndrome during sleep, parents should still ensure that their infants spend some waking hours on their stomachs.[36]

Environmental Modifications for Torticollis Management:

- Placing the baby in a crib with the affected side facing the wall can encourage them to turn their head the other way, promoting better movement.[38]

Manual therapy

[edit]A meta-analysis shows physical therapists specializing in manual therapy have developed effective interventions for the management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT), primarily centered around massage and passive stretching techniques. These interventions are tailored to address the specific needs of pediatric patients, with a focus on stretching the sternocleidomastoid muscle.[38] Various protocols have been proposed, including stretching exercises held for specific durations and repetitions, aimed at increasing blood flow, and promoting muscle relaxation.

Additionally, massage maneuvers such as rhythmic muscle mobilization techniques are employed to mobilize cervical structures and induce relaxation.[38] The systematic review highlights the efficacy of manual therapy and passive stretching in improving cervical range of motion (ROM) in children with CMT. Furthermore, the involvement of caregivers in home exercise programs is emphasized as crucial for optimizing treatment outcomes and promoting motor development while preventing secondary complications.

A systematic review, looked into the possible benefits of using manipulation techniques to counteract infant torticollis. The study considered the impact of manipulation on an infant's sleep, crying, and restlessness as well.[39] This review did not report any adverse effects of using manipulation techniques. It was shown that using manipulation techniques on their own had little to no statistical differences from a placebo group, immediately. When manipulation techniques were combined with physical therapy, there was a change in symptoms compared to the use of physical therapy alone. When targeting the cervical spine, manipulation techniques were shown to shorten treatment duration in infants with head asymmetries.[39]

Microcurrent therapy

[edit]A Korean study has recently[when?] introduced an additional treatment called microcurrent therapy that may be effective in treating congenital torticollis. For this therapy to be effective the children should be under three months of age and have torticollis involving the entire sternocleidomastoid muscle with a palpable mass and a muscle thickness over 10 mm. Microcurrent therapy sends minute electrical signals into tissue to restore the normal frequencies in cells.[27] Microcurrent therapy is completely painless and children can only feel the probe from the machine on their skin.[27]

Microcurrent therapy is thought to increase ATP and protein synthesis as well as enhance blood flow, reduce muscle spasms and decrease pain along with inflammation.[27] It should be used in addition to regular stretching exercises and ultrasound diathermy. Ultrasound diathermy generates heat deep within body tissues to help with contractures, pain and muscle spasms as well as decrease inflammation. This combination of treatments shows remarkable outcomes in the duration of time children are kept in rehabilitation programs: Micocurrent therapy can cut the length of a rehabilitation program almost in half with a full recovery seen after 2.6 months.[27]

About 5–10% of cases fail to respond to stretching and require surgical release of the muscle.[40][41]

Surgery

[edit]Surgical release involves the two heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle being dissected free. This surgery can be minimally invasive and done laparoscopically. Usually surgery is performed on those who are over 12 months old. The surgery is for those who do not respond to physical therapy or botulinum toxin injection or have a very fibrotic sternocleidomastoid muscle.[8] After surgery the child will be required to wear a soft neck collar (also called a Callot's cast). There will be an intense physiotherapy program for 3–4 months as well as strengthening exercises for the neck muscles.[42]

Other treatments

[edit]Other treatments include:[14]

- Rest and analgesics for acute cases

- Diazepam or other muscle relaxants

- Botulinum toxin[43][44]

- Encouraging active movements for children 6–8 months of age

- Ultrasound diathermy

Overview

[edit]CMT is a neck problem that babies are born with or develop soon after birth, causing their neck to be stiff and bent in an awkward position.[38] Besides the sternocleidomastoid muscle, other muscles in the neck can also be affected by CMT, leading to problems moving the head and neck normally.[38] The main goal of treating CMT is to make the sternocleidomastoid muscle stronger and more flexible, so the neck can move better and symptoms can improve.

Prognosis

[edit]Studies and evidence from clinical practice show that 85–90% of cases of congenital torticollis are resolved with conservative treatment such as physical therapy.[36] Earlier intervention is shown to be more effective and faster than later treatments. More than 98% of infants with torticollis treated before 1 month of age recover by 2.5 months of age.[36] Infants between 1 and 6 months usually require about 6 months of treatment.[36] After that point, therapy will take closer to 9 months, and it is less likely that the torticollis will be fully resolved.[36] It is possible that torticollis will resolve spontaneously, but chance of relapse is possible.[11] For this reason, infants should be reassessed by their physical therapist or other provider 3–12 months after their symptoms have resolved.[36]

Other animals

[edit]

In veterinary literature usually only the lateral bend of head and neck is termed torticollis, whereas the analogon to the rotatory torticollis in humans is called a head tilt. The most frequently encountered form of torticollis in domestic pets is the head tilt, but occasionally a lateral bend of the head and neck to one side is encountered.[45]

Head tilt

[edit]Causes for a head tilt in domestic animals are either diseases of the central or peripheral vestibular system or relieving posture due to neck pain. Known causes for head tilt in domestic animals include:

- Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection in rabbits[46]

- parasitic infestation by the nematode (roundworm) Baylisascaris procyonis in rabbits

- Inner ear infection

- Hypothyroidism in dogs[47]

- Disease of cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear nerve) through trauma, infection, inflammation, or neoplasia

- Disease of the brain stem caused by stroke, trauma, or neoplasia

- Damage to the vestibular organ due to toxicity, inflammation or impaired blood supply

- Geriatric vestibular syndrome in dogs

Notes

[edit]- ^ Not be confused with the genus Loxia covering those bird species known as "crossbills", which was assigned by Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner because of the obvious similarities.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dauer, W.; Burke, RE; Greene, P; Fahn, S (1998). "Current concepts on the clinical features, aetiology and management of idiopathic cervical dystonia". Brain. 121 (4): 547–60. doi:10.1093/brain/121.4.547. PMID 9577384.

- ^ a b c Cooperman, Daniel R. (January 1997). "The Differential Diagnosis of Torticollis in Children". Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 17 (2): 1–11. doi:10.1080/J006v17n02_01.

- ^ Velickovic, M; Benabou, R; Brin, MF (2001). "Cervical dystonia pathophysiology and treatment options". Drugs. 61 (13): 1921–43. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161130-00004. PMID 11708764. S2CID 46954613.

- ^ "Cervical dystonia - Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ a b c Dauer, W. (1998-04-01). "Current concepts on the clinical features, aetiology and management of idiopathic cervical dystonia". Brain. 121 (4): 547–560. doi:10.1093/brain/121.4.547. PMID 9577384.

- ^ Papapetropoulos, S; Tuchman, A; Sengun, C; Russell, A; Mitsi, G; Singer, C (2008). "Anterocollis: Clinical features and treatment options". Medical Science Monitor. 14 (9): CR427–30. PMID 18758411.

- ^ Papapetropoulos, Spiridon; Baez, Sheila; Zitser, Jennifer; Sengun, Cenk; Singer, Carlos (2008). "Retrocollis: Classification, Clinical Phenotype, Treatment Outcomes and Risk Factors". European Neurology. 59 (1–2): 71–5. doi:10.1159/000109265. PMID 17917462. S2CID 30159732.

- ^ a b Saxena, Amulya (2015). "Pediatric torticollis surgery treatment & management". Medscape.

- ^ "Torticollis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov.

- ^ "Torticollis (Wryneck)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-04-28. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tomczak, Kinga K.; Rosman, N. Paul (March 2013). "Torticollis". Journal of Child Neurology. 28 (3): 365–378. doi:10.1177/0883073812469294. PMID 23271760. S2CID 216099695.

- ^ "Torticollis". www.childrenshospital.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-21. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ a b c Xiao, Yuanyi; Chi, Zhenhai; Yuan, Fuqiang; Zhu, Daocheng; Ouyang, Xilin; Xu, Wei; Li, Jun; Luo, Zhaona; Chen, Rixin; Jiao, Lin (28 August 2020). "Effectiveness and safety of massage in the treatment of the congenital muscular torticollis: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol". Medicine. 99 (35) e21879. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021879. PMC 7458238. PMID 32871916.

- ^ a b c d e Carenzio, G (2015). "Early rehabilitation treatment in newborns with congenital muscular torticollis". Phys Rehabil Med. 51 (5): 539–45. PMID 25692687.

- ^ Boricean, ID (2011). "Understanding ocular torticollis in children". Oftalmologia. 55 (1): 10–26. PMID 21774381.

- ^ Cheng, JC; Wong, MW; Tang, SP; Chen, TM; Shum, SL; Wong, EM (2001). "Clinical determinants of the outcome of manual stretching in the treatment of congenital muscular torticollis in infants. A prospective study of eight hundred and twenty-one cases". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 83-A (5): 679–87. doi:10.2106/00004623-200105000-00006. PMID 11379737. S2CID 999791.

- ^ "Clinical Practice Guidelines: Congenital Torticollis". www.rch.org.au. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Rosman, Paul; Douglass, Laurie; Paolini, Jan (30 January 2009). "The Neurology of Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis of Infancy: Report of 10 New Cases and Review of the Literature". Journal of Child Neurology. 24 (2): 155–160. doi:10.1177/0883073808322338. PMID 19182151. S2CID 35657143.

- ^ "Clinical Practice Guidelines: Acquired Torticollis". www.rch.org.au. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Boussetta, Rim; Zairi, Mohamed; Sami, Sami Bouchoucha; Lafrem, Rafik; Msakeni, Ahmed; Saied, Walid; Nessib, Nebil (2020). "Torticollis as a sign of spinal tuberculosis". Pan African Medical Journal. 36: 277. doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.36.277.22977. PMC 7545976. PMID 33088406.

- ^ Bocciolini, C; Dall'Olio, D; Cunsolo, E; Cavazzuti, PP; Laudadio, P (August 2005). "Grisel's syndrome: a rare complication following adenoidectomy". Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 25 (4): 245–249. PMC 2639892. PMID 16482983.

- ^ Dressler, D.; Benecke, R. (2005). "Diagnosis and management of acute movement disorders". Journal of Neurology. 252 (11): 1299–306. doi:10.1007/s00415-005-0006-x. PMID 16208529. S2CID 189867541.

- ^ "Cervical dystonia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ Trochlear Nerve Palsy (Fourth Nerve Palsy) at eMedicine

- ^ a b c "Torticollis in Children and Adolescents | PM&R KnowledgeNow". 2017-02-27. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ a b "Torticollis". Yale Medicine. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ a b c d e Kwon, D.R. (2014). "Efficacy of micro current therapy in infants with congenital muscular torticollis involving the entire sternocleidomastoid muscle". Clinical Rehabilitation. 28 (10): 983–91. doi:10.1177/0269215513511341. PMID 24240061. S2CID 206484848.

- ^ Mokri, Bahram (December 2014). "Movement disorders associated with spontaneous CSF leaks: a case series". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 34 (14): 1134–1141. doi:10.1177/0333102414531154. PMID 24728303. S2CID 3100453.

- ^ "Acquired Nystagmus: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 30 June 2023.

- ^ Crowner, Beth E. (2007-11-01). "Cervical Dystonia: Disease Profile and Clinical Management". Physical Therapy. 87 (11): 1511–1526. doi:10.2522/ptj.20060272. PMID 17878433.

- ^ Płomiński, Janusz; Olesińska, Jolanta; Kamelska-Sadowska, Anna Malwina; Nowakowski, Jacek Józef; Zaborowska-Sapeta, Katarzyna (20 December 2023). "Congenital Muscular Torticollis—Current Understanding and Perinatal Risk Factors: A Retrospective Analysis". Healthcare. 12 (1): 13. doi:10.3390/healthcare12010013. PMC 10778664. PMID 38200919. ProQuest 2912741403.

- ^ "Botox".

- ^ Kaplan, Sandra L.; Coulter, Colleen; Fetters, Linda (2013). "Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis". Pediatric Physical Therapy. 25 (4): 348–394. doi:10.1097/pep.0b013e3182a778d2. PMID 24076627. S2CID 5343916.

- ^ Sargent, Barbara; Coulter, Colleen; Cannoy, Jill; Kaplan, Sandra L. (October 2024). "Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis: A 2024 Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Physical Therapy Association Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy". Pediatric Physical Therapy. 36 (4): 370–421. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000001114. ISSN 0898-5669. PMC 8568067. PMID 39356257.

- ^ Castilla, Adrianna; Gonzalez, Mariah; Kysh, Lynn; Sargent, Barbara (2023-01-11). "Informing the Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis Clinical Practice Guideline: A Systematic Review". Pediatric Physical Therapy. 35 (2): 190–200. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000993. ISSN 0898-5669. PMID 36637442.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kaplan, Sandra L.; Coulter, Colleen; Sargent, Barbara (October 2018). "Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis: A 2018 Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline From the APTA Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy". Pediatric Physical Therapy. 30 (4): 240–290. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000544. PMC 8568067. PMID 30277962. S2CID 52909510.

- ^ Graham, John M. (2007), "Torticollis-Plagiocephaly Deformation Sequence", Smith's Recognizable Patterns of Human Deformation, Elsevier, pp. 141–156, doi:10.1016/b978-072161489-2.10025-6, ISBN 978-0-7216-1489-2

- ^ a b c d e Blanco-Diaz, Maria; Marcos-Alvarez, Maria; Escobio-Prieto, Isabel; De la Fuente-Costa, Marta; Perez-Dominguez, Borja; Pinero-Pinto, Elena; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, Alvaro Manuel (7 July 2023). "Effectiveness of Conservative Treatments in Positional Plagiocephaly in Infants: A Systematic Review". Children. 10 (7): 1184. doi:10.3390/children10071184. hdl:10261/350376. PMC 10378416. PMID 37508680. ProQuest 2843032121.

- ^ a b Brurberg, Kjetil G.; Dahm, Kristin Thuve; Kirkehei, Ingvild (2018). "Manipulasjonsteknikker ved nakkeasymmetri hos spedbarn" [Manipulation techniques for infant torticollis]. Tidsskrift for den Norske Legeforening (in Norwegian). 138 (1). doi:10.4045/tidsskr.17.1031. hdl:11250/2582088. PMID 30644674. S2CID 203804340.

- ^ Tang, SF; Hsu, KH; Wong, AM; Hsu, CC; Chang, CH (2002). "Longitudinal followup study of ultrasonography in congenital muscular torticollis". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 403 (403): 179–85. doi:10.1097/00003086-200210000-00026. PMID 12360024. S2CID 20606626.

- ^ Hsu, Tsz-Ching; Wang, Chung-Li; Wong, May-Kuen; Hsu, Kuang-Hung; Tang, Fuk-Tan; Chen, Huan-Tang (1999). "Correlation of clinical and ultrasonographic features in congenital muscular torticollis". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 80 (6): 637–41. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90165-X. PMID 10378488.

- ^ Seung, Seo (2015). "Change of facial asymmetry in patients". Medscape.

- ^ Samotus, Olivia; Lee, Jack; Jog, Mandar (2018-03-20). "Personalized botulinum toxin type A therapy for cervical dystonia based on kinematic guidance". Journal of Neurology. 265 (6): 1269–1278. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8819-6. PMID 29557988. S2CID 4043479.

- ^ Safarpour, Yasaman; Jabbari, Bahman (2018-02-24). "Botulinum Toxin Treatment of Movement Disorders". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 20 (2): 4. doi:10.1007/s11940-018-0488-3. PMID 29478149. S2CID 3502413.

- ^ "Head Tilt (Torticollis) in Rabbits: Don't Give Up". www.bio.miami.edu.

- ^ Künzel, Frank; Joachim, Anja (2009). "Encephalitozoonosis in rabbits". Parasitology Research. 106 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1007/s00436-009-1679-3. PMID 19921257. S2CID 11727371.

- ^ Jaggy, André; Oliver, John E.; Ferguson, Duncan C.; Mahaffey, E. A.; Glaus Jr, T. Glaus (1994). "Neurological Manifestations of Hypothyroidism: A Retrospective Study of 29 Dogs". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 8 (5): 328–36. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03245.x. PMID 7837108.