Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dactyly

View on Wikipedia

In biology, dactyly is the arrangement of digits (fingers and toes) on the hands, feet, or sometimes wings of a tetrapod animal. The term is derived from the Ancient Greek word δάκτυλος (dáktulos), meaning "finger."

Sometimes the suffix "-dactylia" is used. The derived adjectives end with "-dactyl" or "-dactylous."

As a normal feature

[edit]Pentadactyly

[edit]Pentadactyly (from Ancient Greek πέντε (pénte), meaning "five") is the condition of having five digits on each limb. It is traditionally believed that all living tetrapods are descended from an ancestor with a pentadactyl limb, although many species have now lost or transformed some or all of their digits by the process of evolution. However, this viewpoint was challenged by Stephen Jay Gould in his 1991 essay "Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies," where he pointed out polydactyly in early tetrapods and described the specializations of digit reduction.[1] Despite the individual variations listed below, the relationship is to the original five-digit model.

In reptiles, the limbs are pentadactylous.

Dogs have tetradactylous paws but the dewclaw makes them pentadactyls. Cats also have dewclaws on their front limbs but not their hind limbs, making them both pentadactyls and tetradactyls.

Tetradactyly

[edit]Tetradactyly (from Ancient Greek τετρα- (tetra-), meaning "four") is the condition of having four digits on a limb, as in many birds, amphibians, and theropod dinosaurs.

Tridactyly

[edit]

Tridactyly (from Ancient Greek τρι- (trí-), meaning "three") is the condition of having three digits on a limb, as in the rhinoceros and ancestors of the horse such as Protohippus and Hipparion. These all belong to the Perissodactyla. Some birds also have three toes, including emus, bustards, and quail.

Didactyly

[edit]Didactyly (from Ancient Greek δι- (di-), meaning "two") or bidactyly is the condition of having two digits on each limb, as in the Hypertragulidae and two-toed sloth, Choloepus didactylus. In humans this name is used for an abnormality in which the middle digits are missing, leaving only the thumb and fifth finger, or big and little toes. Cloven-hoofed mammals (such as deer, sheep and cattle – Artiodactyla) have only two digits, as do ostriches.

Monodactyly

[edit]Monodactyly (from Ancient Greek μόνος (mónos), meaning "one") is the condition of having a single digit on a limb, as in modern horses and other equids (though one study suggests that the frog might be composed of remnants of digits II and IV, rendering horses as not truly monodactyl[2]) as well as sthenurine kangaroos. Functional monodactyly, where the weight is supported on only one of multiple toes, can also occur, as in the theropod dinosaur Vespersaurus. The pterosaur Nyctosaurus retained only the wing finger on the forelimb, rendering it also partially monodactyl.[3]

As a congenital defect

[edit]Among humans, the term "five-fingered hand" is sometimes used to mean the abnormality of having five fingers, none of which is a thumb.[citation needed]

Syndactyly

[edit]

Syndactyly (from Ancient Greek σύν (sún), meaning "together") is a condition where two or more digits are fused together. It occurs normally in some mammals, such as the siamang and most diprotodontid marsupials such as kangaroos. It occurs as an unusual condition in humans.

Polydactyly

[edit]Polydactyly (from Ancient Greek πολύς (polús), meaning "many") is when a limb has more than the usual number of digits. This can be:

- As a result of congenital abnormality in a normally pentadactyl animal. Polydactyly is very common among domestic cats. For more information, see polydactyly.

- Polydactyly in early tetrapod aquatic animals, such as in Acanthostega gunnari (Jarvik 1952), one of an increasing number of genera of stem-tetrapods known from the Upper Devonian, which are providing insights into the appearance of tetrapods and the origin of limbs with digits. It also occurs secondarily in some later tetrapods, such as ichthyosaurs. The use of a term normally reserved for congenital defects reflects that it was regarded as an anomaly at the time, as it was believed that all modern tetrapods have either five digits or ancestors that did.

Oligodactyly

[edit]Oligodactyly (from Greek ὀλίγος (olígos), meaning "few") is having too few digits when not caused by an amputation. It is sometimes incorrectly called hypodactyly or confused with aphalangia, the absence of the phalanx bone on one or (commonly) more digits. When all the digits on a hand or foot are absent, it is referred to as adactyly.[4]

Ectrodactyly

[edit]Ectrodactyly, also known as split-hand malformation, is the congenital absence of one or more central digits of the hands and feet. Consequently, it is a form of oligodactyly. News anchor Bree Walker is probably the best-known person with this condition, which affects about one in 91,000 people.[citation needed] It is conspicuously more common in the Vadoma in Zimbabwe.

-

Tetradactyly

-

Tridactyly (Mikhail Tal)

-

Didactyly

-

Monodactyly

Clinodactyly

[edit]Clinodactyly is a medical term describing the curvature of a digit (a finger or toe) in the plane of the palm, most commonly the fifth finger (the "little finger") towards the adjacent fourth finger (the "ring finger"). It is a fairly common isolated anomaly which often goes unnoticed, but also occurs in combination with other abnormalities in certain genetic syndromes, such as Down syndrome, Turner syndrome and Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

In birds

[edit]

(right foot, top is front)

Anisodactyly

[edit]Anisodactyly is the most common arrangement of digits in birds, with three toes forward and one back. This is common in songbirds and other perching birds, as well as hunting birds such as eagles, hawks, and falcons. This arrangement of digits helps with perching and/or climbing and clinging. This occurs in Passeriformes, Columbiformes, Falconiformes, Accipitriformes, Galliformes and a majority of other birds.

Syndactyly

[edit]Syndactyly, as it occurs in birds, is like anisodactyly, except that the third and fourth toes (the outer and middle forward-pointing toes), or three toes, are fused together almost to their claws, as in the belted kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon).[5] This is often found in Picocoraciae, though rollers, ground rollers, and Piciformes (who are zygodactyl) are exceptions.[6]: 37

Zygodactyly

[edit]

Zygodactyly (from Greek ζυγος, even-numbered) is an arrangement of digits in birds and chameleons, with two toes facing forward (digits 2 and 3) and two back (digits 1 and 4). This arrangement is most common in arboreal species, particularly those that climb tree trunks or clamber through foliage. Zygodactyly occurs in the parrots, woodpeckers (including flickers), cuckoos (including roadrunners), and some owls. Zygodactyl tracks have been found dating to 120–110 million years ago (early Cretaceous), 50 million years before the first identified zygodactyl fossils. All Psittaciformes, Cuculiformes, the majority of Piciformes and the osprey are zygodactyl.[7]

Heterodactyly

[edit]Heterodactyly is like zygodactyly, except that digits 3 and 4 point forward and digits 1 and 2 point back. This is found only in trogons,[8] though the enantiornithean Dalingheornis might also have had this arrangement.[9]

Pamprodactyly

[edit]Pamprodactyly is an arrangement in which all four toes point forward, outer toes (toe 1 and sometimes 4) often if not regularly reversible. It is a characteristic of swifts (Apodidae) and mousebirds (Coliiformes).[6]: 37–38

Chameleons

[edit]The feet of chameleons are organized into bundles of a group of two and a group of three digits which oppose one another to grasp branches in a pincer-like arrangement. This condition has been called zygodactyly or didactyly, but the specific arrangement in chameleons does not fit either definition. The feet of the front limbs in chameleons, for instance, are organized into a medial bundle of digits 1, 2 and 3, and a lateral bundle of digits 4 and 5, while the feet of the hind limbs are organized into a medial bundle of digits 1 and 2, and a lateral bundle of digits 3, 4 and 5.[10] On the other hand, zygodactyly involves digits 1 and 4 opposing digits 2 and 3, which is an arrangement that chameleons do not exhibit in either front or hind limbs.

Aquatic tetrapods

[edit]In many secondarily aquatic vertebrates, the non-bony tissues of the forelimbs and/or hindlimbs are fused into a single flipper. Some remnant of each digit generally remains under the soft tissue of the flipper, though digit reduction gradually occurs such as in baleen whales (mysticeti).[11] Marine mammals evolving flippers represents a classic example of convergent evolution, and by some analyses, parallel evolution.[12]

Full webbing of the digits in the manus and/or pes is present in a number of aquatic tetrapods. Such animals include marine mammals (cetaceans, sirenians, and pinnipeds), marine reptiles (modern sea turtles and extinct ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, metriorhynchids), and flightless aquatic birds such as penguins.[13] Hyperphalangy, or an increase in the number of phalanges beyond ancestral mammal and reptile conditions, is present in modern cetaceans and extinct marine reptiles.[14]

Schizodactyly

[edit]Schizodactyly is a primate term for grasping and clinging with the second and third digit, instead of the thumb and second digit.

See also

[edit]- Artiodactyl – even-toed ungulates, clade Cetartiodactyla

- Perissodactyl – odd-toed ungulates

References

[edit]- ^ Stephen Jay Gould. "Stephen Jay Gould "Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies" 1991". Archived from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

- ^ Solounias, Nikos; Danowitz, Melinda; Stachtiaris, Elizabeth; Khurana, Abhilasha; Araim, Marwan; Sayegh, Marc; Natale, Jessica (2018). "The evolution and anatomy of the horse manus with an emphasis on digit reduction". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (1) 171782. doi:10.1098/rsos.171782. PMC 5792948. PMID 29410871.

- ^ Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691150611.

- ^ József Zákány; Catherine Fromental-Ramain; Xavier Warot & Denis Duboule (1997). "Regulation of number and size of digits by posterior Hox genes: A dose-dependent mechanism with potential evolutionary implications". PNAS. 94 (25): 13695–13700. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9413695Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13695. PMC 28368. PMID 9391088.

- ^ Dudley, Ron (14 February 2016). "Belted Kingfisher With A Fish (plus an interesting foot adaptation)". FeatheredPhotography. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ a b Nupen, Lisa (September–October 2016). "Fancy Footwork: The Dazzling Diversity of Avian Feet" (PDF). African Birdlife. Vol. 4, no. 6. BirdLife South Africa. pp. 34–38. ISSN 2305-042X. Retrieved 4 December 2022 – via FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology.

- ^ Lockley, Martin G.; Li, Rihui; Harris, Jerald D.; Matsukawa, Masaki; Liu, Mingwei (2007). "Earliest zygodactyl bird feet: evidence from Early Cretaceous roadrunner-like tracks" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 94 (8): 657–665. Bibcode:2007NW.....94..657L. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0239-x. PMID 17387416. S2CID 15821251.

- ^ Botelho, João Francisco; Smith-Paredes, Daniel; Nuñez-Leon, Daniel; Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Vargas, Alexander O. (2014-08-07). "The developmental origin of zygodactyl feet and its possible loss in the evolution of Passeriformes". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1788) 20140765. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0765. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4083792. PMID 24966313.

- ^ Zhang, Z.; Hou, L.; Hasegawa, Y.; O'Connor, J.; Martin, L.D.; Chiappe, L.M. (2006). "The first Mesozoic heterodactyl bird from China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 80 (5): 631–635.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher V. & Higham, Timothy E. (2014). "Chameleon anatomy". In Tolley, Krystal A. & Herrel, Anthony (eds.). The Biology of Chameleons. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 7–55. ISBN 978-0-520-27605-5.

- ^ Cooper, Lisa Noelle; Berta, Annalisa; Dawson, Susan D.; Reidenberg, Joy S. (2007). "Evolution of hyperphalangy and digit reduction in the cetacean manus". Anatomical Record. 290 (6): 654–672. doi:10.1002/ar.20532. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 17516431. S2CID 14586607.

- ^ Chikina, Maria; Robinson, Joseph D.; Clark, Nathan L. (2016-09-01). "Hundreds of Genes Experienced Convergent Shifts in Selective Pressure in Marine Mammals". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33 (9): 2182–2192. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw112. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 5854031. PMID 27329977.

- ^ Fish, F.E. (2004). "Structure and Mechanics of Nonpiscine Control Surfaces". IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 29 (3): 605–621. Bibcode:2004IJOE...29..605F. doi:10.1109/joe.2004.833213. ISSN 0364-9059. S2CID 28802495.

- ^ Fedak, Tim J; Hall, Brian K (2004). "Perspectives on hyperphalangy: patterns and processes". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (3): 151–163. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00278.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1571266. PMID 15032905.

External links

[edit]- Coates, Michael (25 April 2005). "Why do most species have five digits on their hands and feet?". Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

Dactyly

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Dactyly refers to the arrangement of digits—such as fingers, toes, or wing elements—on the limbs of tetrapod animals, encompassing aspects like their number, position, fusion, and orientation.[8] This biological concept focuses on how these structures are configured in the autopodia (hand and foot regions) of tetrapods, which are four-limbed vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.[2] The scope of dactyly is strictly limited to tetrapods, excluding invertebrates and non-tetrapod vertebrates like fish, as digits represent a defining evolutionary innovation tied to terrestrial adaptation. The term dactyly originates from foundational studies in comparative anatomy and evolutionary biology, where it emerged as a key descriptor for analyzing limb morphology across vertebrate lineages. In these fields, dactyly has been recognized as a derived character state that distinguishes tetrapods from their aquatic ancestors, marking the transition from fin-like structures to load-bearing limbs capable of supporting weight on land.[2] This framework allows researchers to trace how digit configurations evolved in response to selective pressures during the Devonian period and beyond.[9] A central concept in dactyly is its role in facilitating diverse functional adaptations among tetrapods, influencing locomotion, environmental manipulation, and grasping abilities.[2] For instance, variations in digit arrangement enable specialized movements, such as the weight distribution in amphibian limbs for aquatic-terrestrial transitions or the precise manipulation in mammalian forelimbs.[10] These features underscore dactyly's evolutionary significance in promoting tetrapod diversification and success in varied habitats.[2]Etymology

The term "dactyly" derives from the Ancient Greek word δάκτυλος (dáktulos), meaning "finger," which was also applied to toes in anatomical contexts.[11] This root is combined with numerical prefixes such as πέντα- (penta-, "five") for pentadactyly, τέτρα- (tetra-, "four") for tetradactyly, and τρία- (tri-, "three") for tridactyly to describe specific digit counts.[12] Other prefixes include σύν- (syn-, "together") as in syndactyly for fused digits, and πολύ- (poly-, "many") as in polydactyly for supernumerary digits.[13] In medical terminology, the suffix -dactyly denotes a condition or state related to digits, while -dactyl indicates possession of a certain number or type of digits, following standard Greco-Latin compounding patterns in anatomy.[14] For instance, polydactyly is formed from poly- + daktylos + -ia, where -ia signifies a pathological condition, resulting in a term meaning "many-fingered state."[15] These terms first appeared in anatomical literature during the 17th and 19th centuries, with polydactyly coined in 1670 by Dutch physician Theodor Kerckring to describe a case of extra digits, and syndactyly entering English usage by 1864.[16] Their formation was influenced by the systematic nomenclature traditions established in Linnaean classification, which favored Greek and Latin roots for precise biological descriptions.[17]Normal digit counts in tetrapods

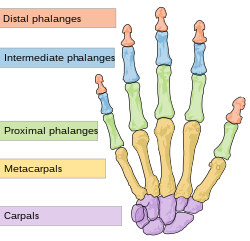

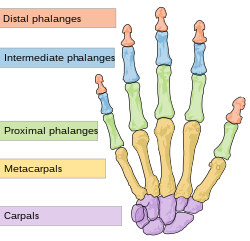

Pentadactyly

Pentadactyly refers to the condition in which a tetrapod limb possesses five digits, representing the ancestral and predominant digit arrangement across most amphibian, reptilian, and mammalian lineages, as well as in early avian forms before subsequent reductions.[2] This configuration provided a versatile structural foundation that facilitated diverse modes of locomotion on land, from walking and grasping to burrowing, enabling the transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments during the Devonian period.[10] The evolutionary origins of pentadactyly trace back to the late Devonian (~375–359 million years ago), where early stem-tetrapods like Acanthostega exhibited polydactyly with eight digits per limb, likely as an experimental phase in fin-to-limb transition from sarcopterygian fish ancestors.[2] By the early Carboniferous (~350 million years ago), the pentadactyl pattern had stabilized as the ground state in more derived forms such as Pederpes, marking a key innovation for efficient weight-bearing and maneuverability on terrestrial substrates.[10] This five-digit arrangement became conserved through developmental mechanisms involving signaling pathways like Sonic hedgehog (Shh), which pattern the autopodal region and support adaptive radiations in tetrapod diversity.[18] In modern tetrapods, pentadactyly is exemplified by the human hand and foot, each bearing five digits adapted for manipulation and bipedal stability; the canine paw, where the dewclaw serves as the reduced first digit alongside four weight-bearing toes; and the crocodilian limb, which retains a fully functional five-toed structure suited for semi-aquatic ambulation.[19] In mammals, such as humans and canines, the phalangeal formula is typically 2-3-3-3-3, denoting two phalanges in the first (preaxial) digit and three in each of the others, while in crocodilians it is 2-3-4-5-3.[20][21] These patterns optimize flexibility and strength. While pentadactyly remains overt in many species, variations occur where digits are vestigial or incorporated into the limb skeleton, such as in equids where the splint bones represent the highly reduced second and fourth metacarpals and metatarsals, remnants of the ancestral five-digit array modified for cursorial speed.[22]Tetradactyly

Tetradactyly refers to the condition in which a tetrapod limb possesses four functional digits, typically resulting from the reduction or absence of the first digit (equivalent to the thumb or hallux) while retaining digits II through V.[23] This arrangement contrasts with the ancestral pentadactyl state and is common in certain lineages where limb streamlining enhances mobility. In such cases, the reduced digit I often serves a vestigial role or is entirely absent, allowing the remaining digits to bear primary weight and facilitate specialized locomotion.[8] In evolutionary terms, tetradactyly emerged prominently among theropod dinosaurs and their avian descendants as an adaptation favoring increased speed and efficiency in bipedal or aerial movement. Theropod ancestors, originating from archosauriforms, exhibited this digit reduction to optimize hindlimb propulsion for cursorial pursuits, reducing drag and improving stride efficiency.[24] This trait persisted and evolved in modern birds, where it supports both terrestrial running and flight initiation by minimizing limb mass.[25] Prominent examples of tetradactyly occur in most modern birds, where the foot features four digits with II, III, and IV directed forward for perching and propulsion, and I as a reduced backward-facing hallux.[26] Among lizards, tetradactyly is observed in certain scincid genera like Brachymeles, the Philippine slender skinks, which have evolved reduced limbs with four digits per manus and pes adapted to fossorial lifestyles.[27] The functional advantages of tetradactyly include enhanced streamlining for high-speed running in theropods and balanced weight distribution for takeoff in birds, achieved through phalangeal shortening in the outer digits to maintain stability during rapid maneuvers.[28] This configuration reduces overall limb inertia, allowing for quicker acceleration and energy-efficient locomotion compared to more digitally complex forms.[29] Fossil evidence documents the transition from pentadactyly to tetradactyly among Triassic archosaurs, particularly in dinosauromorphs, where Middle Triassic trackways show progressive reduction of digits I and V, yielding tetradactyl imprints indicative of emerging bipedalism.[30] Such footprints from Early to Middle Triassic deposits reveal intermediate stages, with archosauriforms displaying variable digit counts that stabilized at four in later theropod lineages.[28] This reduction often preceded further loss to tridactyly in more derived cursorial forms.[30]Tridactyly

Tridactyly refers to the condition in which tetrapods possess three functional digits per limb, typically digits II, III, and IV, with digits I and V either absent or reduced to vestigial structures such as splint bones.[31] This configuration represents an intermediate stage of digit reduction from the ancestral pentadactyly, often associated with adaptations for terrestrial locomotion in fast-moving species.[32] In evolutionary terms, tridactyly facilitates enhanced speed and agility by reducing limb weight and improving stability on varied terrains, particularly in cursorial animals. For instance, in perissodactyl ungulates, this digit arrangement supports efficient weight distribution during rapid movement, as seen in modern rhinoceroses (family Rhinocerotidae), which bear three toes on both fore- and hindfeet, with the central digit III being the largest and primary weight-bearer.[33] Fossil equids like those in the tribe Hipparionini (e.g., Hipparion and Cormohipparion), prevalent from about 17 to 1 million years ago, exemplified tridactyly adapted for maneuvering in wooded Miocene environments, before further reduction to monodactyly in modern Equus.[31] Similarly, many theropod dinosaurs, including basal forms and advanced coelurosaurs ancestral to birds, exhibited tridactyl manus and pes, promoting lightweight, bipedal sprinting capabilities that contributed to their ecological success during the Mesozoic era.[34] The phalangeal formula in tridactyl limbs often follows a pattern of 0-3-3-3 (indicating no phalanges in absent digits, followed by three phalanges each in digits II, III, and IV), providing structural stability for load-bearing while minimizing mass. In theropod dinosaurs, the pedal formula is typically II³-III⁴-IV⁵ (three phalanges in digit II, four in III, five in IV), which supports dynamic propulsion in predatory lifestyles.[34] Developmentally, tridactyly arises through regulation by Hox genes, particularly clusters HoxA and HoxD, which control limb patterning and digit formation via dosage-dependent mechanisms that suppress the development of lateral digits. Posterior Hoxd genes (e.g., Hoxd11–13) promote digit reduction by influencing mesenchymal condensation spacing in the limb bud, leading to the loss or vestigialization of digits I and V across multiple tetrapod lineages.[35] This genetic framework allows evolutionary flexibility, enabling tridactyly as an adaptation for speed without compromising overall limb integrity.[36]Didactyly

Didactyly refers to the condition in which a limb possesses two digits, frequently configured with one acting as an opposable structure to enable secure gripping. This arrangement supports specialized functions in grasping or perching, distinguishing it from more common pentadactyl patterns by emphasizing efficiency in targeted manipulation over broad versatility.[37] In evolutionary terms, didactyly has arisen as an adaptation in arboreal mammals to enhance prehensility, allowing prolonged suspension and precise handling in tree-dwelling lifestyles. For instance, in two-toed sloths (Choloepus spp.), the forelimbs exhibit this reduction, with only digits II and III functional and syndactylous, forming long, hook-like claws that facilitate hanging upside down from branches for extended periods.[38] The functional advantages of didactyly include improved prehensile capability, where the limited digits concentrate strength and flexibility for secure holds, and elongated phalanges extend reach without excess weight, optimizing energy use in slow, suspensory locomotion. In sloths, this configuration supports a low-metabolic arboreal existence, minimizing limb mass while maximizing hook-like stability.[38] Genetically, didactyly involves selective apoptosis during embryonic limb development, where programmed cell death eliminates interdigital tissue to separate digits but also modulates patterning to suppress formation of additional ones, sculpting the final two-digit structure. This process, mediated by factors like bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), ensures precise limb morphology tailored to ecological demands.[39] Further evolutionary reduction to a single digit, as in monodactyly, can occur through intensified suppression of digit primordia.[39]Monodactyly

Monodactyly describes the condition in tetrapod limbs where only one functional digit is present, with all others absent or reduced to vestigial structures. This extreme form of digit reduction contrasts sharply with the ancestral pentadactyly seen in early tetrapods and serves as the endpoint in evolutionary series of decreasing digit number. It is relatively rare across tetrapods, occurring predominantly in derived mammalian lineages such as perissodactyls, where it has evolved independently multiple times.[31] A prominent evolutionary example of monodactyly is found in equids, including modern horses (Equus caballus), where each limb terminates in a single robust toe bearing a keratinized hoof. This trait first appeared in full form during the early late Miocene in species like Pliohippus, evolving from tridactyl ancestors through progressive loss of lateral digits. In equids, the single digit plays a critical functional role in propulsion during high-speed cursorial locomotion, with the central phalanges reinforced for weight-bearing and shock absorption to enable sustained running over hard terrain.[31][40] Developmentally, monodactyly in equids arises from the initial formation of five digit condensations in the embryonic limb bud, followed by the complete suppression of the lateral four through targeted cell death (apoptosis) and fusion into rudimentary splint bones. This process involves alterations in key signaling pathways, including Sonic hedgehog (Shh) from the zone of polarizing activity, which patterns the anterior-posterior axis, and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), which regulate interdigital apoptosis and chondrogenesis to eliminate non-central primordia.[41][42]Congenital abnormalities

Syndactyly

Syndactyly is a congenital malformation characterized by the fusion of two or more adjacent digits, which may involve only soft tissue (simple syndactyly) or include bony unions (complex syndactyly). This condition results from incomplete separation of digits during embryonic development due to failure of programmed cell death (apoptosis) in the interdigital necrotic zones.[4] It is the most common congenital anomaly of the hand, accounting for approximately 20-40% of all hand malformations.[4] The prevalence of syndactyly is estimated at 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 3,000 live births, with a higher incidence in males and often bilateral involvement.[43] It can occur in isolation or as part of genetic syndromes, such as Apert syndrome (associated with FGFR2 mutations) or Poland syndrome. Inheritance is typically autosomal dominant with variable penetrance, though sporadic cases are common. Environmental factors, like amniotic band syndrome, can also contribute.[4] In animals, syndactyly is observed in breeds like the Norwegian Lundehund dog, where it aids in specific locomotion but can be pathological if excessive.[44] Clinically, syndactyly may lead to functional impairments, such as reduced dexterity or nail deformities, particularly in complex forms involving the thumb and index finger. Diagnosis is clinical, often confirmed by radiographs to assess bony involvement. Treatment usually involves surgical separation, ideally performed between 6-18 months of age to allow for normal growth and minimize complications like web creep.[45] Multidisciplinary care, including genetic counseling, is recommended for syndromic cases.Polydactyly

Polydactyly is a congenital limb malformation defined by the presence of supernumerary digits, exceeding the typical five per limb in humans.[5] It is classified into preaxial (affecting the thumb or radial side), postaxial (affecting the little finger or ulnar side), central, or mixed forms based on the location of the extra digit.[46] This condition arises from disruptions in limb patterning during embryonic development and can occur in isolation or as part of broader syndromes. The prevalence of polydactyly in humans varies by type and ethnicity, occurring in approximately 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,000 live births overall.[47] Postaxial polydactyly, for instance, affects 1 to 2 per 1,000 births globally, with higher rates in individuals of African descent (1 in 100 to 1 in 300).[5] Inheritance often follows an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance in familial cases, though sporadic occurrences are common.[48] Non-syndromic forms predominate, but polydactyly also features in syndromes such as Bardet-Biedl syndrome, where postaxial extra digits accompany retinal dystrophy, obesity, and renal anomalies.[49] In animals, polydactyly is well-documented in cats, particularly the Maine Coon breed, where it manifests as an autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity, often resulting in extra toes on the paws.[50] Embryologically, polydactyly stems from a failure of programmed cell death (apoptosis) in the interdigital zones of the developing limb bud, leading to persistent digit separation issues.[5] A key molecular mechanism involves ectopic or overexpressed signaling from the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) gene, which regulates anterior-posterior limb patterning; mutations in SHH regulatory elements, such as the zone of polarizing activity regulatory sequence (ZRS), disrupt this balance and promote extra digit formation.[51] Historically, polydactyly was interpreted as an atavism, a supposed reversion to ancestral multi-digit forms in vertebrates, reflecting early evolutionary theories of limb development.[52] In modern practice, surgical intervention is the standard approach for functional or aesthetic correction, with techniques ranging from simple ligation or excision for rudimentary digits to complex reconstruction involving osteotomy and soft tissue realignment for more developed extras.[53] Polydactyly thus contrasts with the standard pentadactyly by introducing excess digits that may impair hand or foot function if untreated.Oligodactyly

Oligodactyly is a congenital malformation characterized by the presence of fewer than the normal number of digits on a hand or foot, typically fewer than five per limb, resulting from disrupted limb development during embryogenesis.[54] This condition arises due to failure in the proper differentiation of the apical ectodermal ridge in the first trimester of pregnancy, leading to incomplete formation of digital structures.[55] It represents a type of limb reduction defect, where digits may be absent, hypoplastic, or malformed from the outset.[56] The causes of oligodactyly include both genetic and environmental factors. Genetically, it is associated with various syndromes, such as Weyers ulnar ray/oligodactyly syndrome, which involves mutations leading to variable ray reductions in the limbs, and Fanconi anemia, where radial ray defects often result in absent or hypoplastic thumbs, effectively reducing digit count.[57][58] Environmental influences, notably prenatal exposure to teratogens like thalidomide during critical periods of limb bud development, can induce oligodactyly as part of broader reduction defects.[56] These etiologies often interact, with genetic predispositions potentially exacerbating environmental risks. Oligodactyly manifests in symmetric or asymmetric forms, with bilateral involvement being common in syndromic cases but unilateral presentations occurring in isolated or amniotic band-related instances.[59] It frequently occurs as a component of longitudinal or transverse limb reduction defects, where the absence of digits may accompany proximal skeletal anomalies.[56] A specific presentation, such as that seen in ectrodactyly, can contribute to oligodactyly through central digit absence.[55] The condition is rare, with an estimated incidence ranging from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 births, depending on the subtype and associated syndrome.[59] Its association with Fanconi anemia underscores the need for screening in cases of congenital limb anomalies, as up to 50-60% of affected individuals exhibit skeletal malformations.[58] Diagnosis of oligodactyly is often achieved prenatally through ultrasound imaging, which can detect reduced digit counts as early as the second trimester, allowing for genetic counseling and planning.[60] Postnatally, clinical examination and radiographic studies confirm the extent of reduction. Management focuses on functional rehabilitation, with prosthetic devices fitted to improve grip and mobility in cases of significant digit loss; surgical interventions, such as toe-to-hand transfers, may be considered for severe unilateral oligodactyly to enhance hand function.[61] Multidisciplinary care, including orthopedic and genetic specialists, is essential for optimizing outcomes.[55]Ectrodactyly

Ectrodactyly, commonly referred to as split hand/foot malformation or "lobster claw" deformity, is a congenital limb malformation characterized by the absence or severe hypoplasia of one or more central digits, typically the 2nd, 3rd, and/or 4th fingers or toes, resulting in a prominent V-shaped cleft in the hand or foot.[62] This central deficiency divides the limb into two distinct parts, with the thumb and fifth digit often preserved but sometimes rotated or syndactylous, leading to functional and cosmetic challenges.[63] Ectrodactyly serves as a specific subtype of oligodactyly, focusing on this patterned central absence rather than generalized digit reduction.[64] The condition arises primarily from genetic mutations, most notably in the TP63 gene on chromosome 3q28, which encodes a transcription factor critical for ectodermal and limb development.[65] In the context of ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting (EEC) syndrome, these heterozygous missense mutations exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance, with variable expressivity and penetrance.[66] EEC syndrome integrates ectrodactyly with additional features such as ectodermal defects, though isolated ectrodactyly can occur via mutations in other loci like DLX5/DLX6 or HOXD13.[67] The prevalence of ectrodactyly is estimated at 1 in 90,000 to 1 in 150,000 live births, with manifestations that can be unilateral or bilateral, the latter occurring in a substantial proportion of cases.[68][62] Associated issues frequently include nail dysplasia, manifesting as hypoplastic, ridged, or absent nails on the affected digits, alongside broader ectodermal defects in syndromic forms such as sparse hair, hypohidrosis, and dental anomalies.[69] These complications can impair grip, balance, and sensation, often necessitating multidisciplinary management. Surgical reconstruction, typically performed in stages during childhood, aims to close the cleft, centralize the thumb, and improve opposition and stability, using techniques like osteotomies and soft tissue transfers to enhance function.[69][70] In veterinary contexts, ectrodactyly is rare but documented in certain animal models, including sporadic cases in dogs and a hereditary, often lethal form in Holstein cattle breeds, providing insights into genetic mechanisms through comparative studies.[71][72]Clinodactyly

Clinodactyly refers to a congenital angular deviation or curvature of one or more digits, most commonly the fifth finger (little finger), toward the radial side (midline of the hand), with an angulation exceeding 10 degrees in the coronal plane.[73] This bending typically occurs at the distal interphalangeal joint and results from an abnormal trapezoidal or delta-shaped middle phalanx, which shortens the bone and causes the longitudinal bracket creep deformity.[73] The condition is often bilateral and primarily affects the hands, though it can involve toes as well.[73] The primary cause of clinodactyly is the congenital shortening or malformation of the middle phalanx, leading to an imbalance in the collateral ligaments and joint alignment.[73] It frequently appears as an isolated trait but is associated with various genetic syndromes, notably Down syndrome, where it occurs in 35% to 79% of affected individuals due to trisomy 21-related skeletal anomalies.[74] Prevalence in the general population ranges from 1% to 19.5%, with higher rates reported in certain ethnic groups and a slight male predominance; it is typically asymptomatic and requires no intervention unless severe.[73] Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on physical examination to measure the radial deviation angle, often confirmed by plain radiographs that reveal the shortened middle phalanx and curvature.[73] Treatment is rarely needed for mild cases, as the condition seldom impairs function; observation or splinting may suffice for cosmetic concerns, while surgical correction—such as reverse wedge osteotomy—is reserved for angles greater than 30-45 degrees causing functional limitations.[74] Unlike camptodactyly, which features permanent flexion contracture at the proximal interphalangeal joint, clinodactyly involves fixed lateral angulation without flexion.[75]Schizodactyly

Schizodactyly is a congenital malformation characterized by the longitudinal bifurcation or forking of one or more digits, resulting in a split appearance without associated absence of tissue. This condition represents the opposite of syndactyly, where digits fail to separate, as schizodactyly involves excessive division or duplication during digit formation.[76] The malformation arises from disruptions in embryogenesis, particularly during the differentiation and segmentation of digital rays in the limb bud, leading to incomplete fusion of phalangeal elements or the development of supernumerary branches attached to an existing digit. It is often classified as a variant of polydactyly, specifically polyphalangy, where the extra structure emerges longitudinally from a primary digit. In natural populations, such anomalies are linked to environmental factors, genetic predispositions, or developmental perturbations, though specific etiologies vary by species.[77][78] Schizodactyly is rare, with prevalence in amphibian populations generally below 5%, considered within natural baseline levels for morphological anomalies unless elevated by external stressors. It is distinct from conditions involving tissue reduction, focusing instead on structural division without loss of digital elements. Familial or recurrent cases have been noted in monitored wild populations, suggesting potential heritable components in affected lineages.[79][77] Examples include cases in amphibians, such as the smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris), where schizodactyly manifests as a forked hind limb digit resembling a specific polydactyly form. In the striped snouted treefrog (Scinax squalirostris), an extra toe bifurcates from the fourth toe of the left hind limb, observed in adult specimens from southeastern Brazil. Similarly, in the moor frog (Rana arvalis), a supernumerary toe branches from a normal digit in the foot, bending distinctly away without impacting overall mobility. These instances highlight schizodactyly's occurrence across anuran and caudatan species during early developmental stages.[76][80][81] Treatment in affected individuals, particularly if functional impairment occurs, may involve surgical reconstruction to realign or remove the bifurcated segment, though such interventions are uncommon in wild populations. Genetic counseling is recommended for captive breeding programs or monitored lineages showing inheritance patterns to mitigate recurrence.[82]Digit arrangements in birds

Anisodactyly

Anisodactyly represents the predominant digit arrangement in avian feet, featuring digits II, III, and IV oriented forward while digit I, known as the hallux, points backward to enable opposition against the other toes.[83] This configuration is characterized by a standard phalangeal formula of 2-3-4-5 phalanges for digits I through IV, respectively, with the forward digits (II, III, IV) possessing 3, 4, and 5 phalanges.[84] The arrangement supports precise grasping, as the hallux can oppose the forward toes, forming a vice-like grip around perches or objects.[85] Evolutionarily, anisodactyly is the ancestral condition for modern birds (Neornithes), derived from theropod dinosaurs through the posterior rotation of the hallux from its original forward position.[86] This toe orientation is evident in early avialans like Archaeopteryx and persists in approximately 80–90% of extant bird species, including the diverse order Passeriformes (passerines or songbirds) and other groups such as Columbiformes (pigeons and doves).[83] For instance, in songbirds like robins (Turdus migratorius) and finches (Fringilla spp.), the structure optimizes branch perching, while in pigeons (Columba livia), it facilitates both perching and ground foraging.[83] The functional advantages of anisodactyly include enhanced stability for perching on narrow or irregular surfaces, achieved through the opposable hallux and the collective support of the three forward toes, which distribute weight evenly and prevent slippage.[87] In locomotion, this setup promotes efficient forward propulsion during walking or hopping on the ground, as the aligned forward digits generate thrust while the hallux provides balance.[88] Variations occur in hallux size and mobility; in arboreal species, the hallux is often elongated for stronger grip, whereas in some ground-dwelling birds, it may be reduced, and limited reversibility—allowing the hallux to rotate slightly forward—enhances versatility in certain perching maneuvers.[83] This basic arrangement forms the foundation for derived foot types, such as zygodactyly in climbing birds.[85]Zygodactyly

Zygodactyly refers to a distinctive toe arrangement in birds characterized by digits II and III directed forward and digits I (the hallux) and IV directed backward, forming a paired opposition that enhances grip strength.[86] This configuration contrasts with the typical anisodactyly of most perching birds and is the second most common foot type among avian species. In certain zygodactyl birds, such as owls and ospreys, the arrangement is reversible, with the fourth toe capable of pivoting forward to adopt a more anisodactyl-like posture when needed for tasks like grasping prey during flight.[89][90] This toe pattern represents an evolutionary adaptation for arboreal lifestyles, particularly in species that climb tree trunks or manipulate objects, such as parrots (Psittaciformes), woodpeckers (Piciformes), and owls (Strigiformes).[91] It provides a secure, vise-like grasp on vertical surfaces, enabling efficient foraging and perching in complex environments like bark or branches. Examples include cuckoos (Cuculiformes), which use it for climbing vegetation, and woodpeckers, where the opposed toes brace against rough substrates during pecking. Zygodactyly has evolved independently at least four times in modern birds, originating from anisodactyly ancestors to suit these specialized niches.[92] The development of zygodactyly arises through asymmetric actions of foot muscles during embryogenesis, which induce the retroversion of digit IV from its initial forward position.[91] Experimental paralysis of these muscles in budgerigar embryos results in failure of this reversal, producing an anisodactyl foot instead. Zygodactyly occurs in approximately 10–12% of extant bird species and has prehistoric roots, with fossil evidence of zygodactyl feet documented in Eocene deposits like the Green River Formation, indicating its ancient origins among early avian lineages.[93]Syndactyly

Syndactyly in birds refers to a foot morphology where two or more toes, typically the third and fourth (outer and middle forward-pointing toes), are fused along part or most of their length, resulting in a shared broad sole that enhances surface area for grip.[94] This arrangement is a modification of the basal anisodactyl condition, where three toes point forward and one backward, but with fusion providing structural reinforcement.[95] The fusion creates a paddle-like or broadened structure that aids in perching on unstable or smooth substrates, such as reeds or branches near water.[96] There are variations in the extent of fusion, ranging from partial syndactyly, where toes are joined only at the base or for a portion of their length, to more complete forms where the toes are united for most of their proximal length.[92] Partial fusion is common in many Coraciiformes, with intermediate examples showing varying degrees of joining. More complete syndactyly occurs in species like kingfishers, where the fused toes form a robust unit.[97] This morphology plays an adaptive role in locomotion and foraging, particularly for species that perch on vertical or slippery surfaces or excavate nests in soft soil. In kingfishers (Alcedinidae), the fused toes facilitate digging burrows in riverbanks and gripping perches while hunting aquatic prey.[96] Similarly, in bee-eaters (Meropidae) and hornbills (Bucerotidae), the broad sole improves adherence to substrates during aerial or arboreal activities.[92] Syndactyly is prevalent among Coraciiformes, many of which inhabit wetland or riparian environments, supporting wading or swimming-related behaviors through enhanced stability.[87] Evolutionarily, syndactyly derives from the anisodactyl arrangement ancestral to most birds, arising through modifications in toe orientation and fusion.[98] Its genetic basis involves disruptions in interdigital necrosis, the programmed cell death process that normally separates digits during embryonic development; failure of this necrosis in specific regions leads to persistent tissue union between toes.[99] In birds, this is evident from necrotic zones observed in interdigital spaces during limb bud regression, a mechanism conserved across reptiles and avians.[100]Heterodactyly

Heterodactyly refers to a toe arrangement in avian feet where digits I and II are directed backward and digits III and IV forward, differing from the more common zygodactyl pattern. This fixed configuration provides a unique opposition for gripping. This foot type is unique to trogons (Trogoniformes), a clade of colorful, forest-dwelling birds adapted for perching in the understory. The arrangement supports precise grasping of foliage and branches in dense vegetation, aiding in gleaning insects and fruits. Heterodactyly enhances stability on slender supports, serving as an evolutionary specialization for their arboreal, non-climbing lifestyle. Heterodactyly is extremely rare, occurring only in trogons (~45 species), representing less than 0.5% of extant birds. Anatomical studies highlight the reversed inner toe (II) as a derived trait, with fossil evidence limited but suggesting origins in early Paleogene avialans.Pamprodactyly

Pamprodactyly refers to a reversible digit arrangement in birds where digits I (hallux) and IV can rotate, allowing all four digits to face forward when needed, in addition to other configurations. This deviates from the standard anisodactyly prevalent in most avian species, where the hallux points rearward to facilitate perching on branches.[94] This arrangement is rare, occurring in less than 5% of bird species, and primarily contrasts with the perching-adapted anisodactyly by enabling versatile ground-based or clinging activities.[83] Pamprodactyly is exemplified in buttonquails (family Turnicidae) and certain rails (family Rallidae), both of which exhibit adaptations suited to ground-dwelling lifestyles involving scratching and probing for food. These birds belong to the order Gruiformes, where the condition reflects a secondary evolutionary modification from ancestors with more versatile, backward-facing hallux for climbing or grasping.[101][83] The functional advantages include enhanced efficiency in forward-directed digging and foraging, as the phalanges are aligned to support powerful pushing motions against soil or leaf litter, aiding in uncovering invertebrates and seeds during ground-based activities, while reversibility allows occasional perching.[101]Adaptations in other tetrapods

Chameleons

Chameleons exhibit a unique form of zygodactyly among reptiles, characterized by the division of their digits into two opposable bundles: digits II and III on one side versus digits IV and V on the other, creating a pincer-like grip ideal for grasping slender branches. This arrangement allows for a vise-like hold that enhances stability during arboreal locomotion. Anatomically, the phalanges within each bundle are partially fused, providing rigidity while specialized muscles enable reversible opposition between the bundles, permitting the foot to alternate between gripping and releasing positions with precision. This muscular control is facilitated by tendons and ligaments that coordinate the flexion and extension, distinguishing chameleon feet from the more rigid zygodactyl arrangements in other taxa. This adaptation evolved independently in chameleons to support their arboreal lifestyle in forested environments, where precise clinging to irregular surfaces is essential for foraging, predator avoidance, and territorial movement. All species within the Chamaeleonidae family, comprising approximately 236 extant chameleon species as of 2025 primarily distributed across Africa, Madagascar, and southern Asia, possess this zygodactyl foot structure, which exemplifies an extreme specialization for branch clinging unmatched in other lizards.[102] For instance, in species like the veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus), this grip supports slow, deliberate climbing on thin twigs, minimizing energy expenditure. The chameleon foot bears a functional similarity to the opposable digits of primate hands, enabling manipulative precision in a quadrupedal reptile, though it lacks the dexterity for object manipulation beyond locomotion. This parallel underscores convergent evolution for arboreal niches, akin in broad form to zygodactyly in birds but arising separately in squamates.Aquatic tetrapods

Aquatic tetrapods, including cetaceans, sirenians, and pinnipeds, exhibit specialized digit arrangements in their forelimbs and hindlimbs to facilitate propulsion and maneuverability in water, often involving elongation, fusion, or increased phalangeal counts beyond the typical tetrapod condition of three phalanges per digit.[103] These adaptations contrast with terrestrial tetrapods by prioritizing streamlined flipper shapes for hydrodynamic efficiency over grasping or weight-bearing functions.[103] In cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises), the forelimbs form rigid, paddle-like flippers characterized by hyperphalangy—an increase in phalangeal elements arranged linearly within digits—and varying degrees of digit reduction. Toothed whales (odontocetes) typically retain a pentadactylous (five-digit) arrangement, with pronounced hyperphalangy in digits II and III, where phalange counts can reach 5–8 in species like the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus).[103] Baleen whales (mysticetes), such as the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), are generally tetradactylous, having lost the first metacarpal and associated elements around 14 million years ago, while exhibiting hyperphalangy primarily in digits III and IV (5–7 phalanges).[103] This hyperphalangy, which evolved independently at least by 7–8 million years ago in mysticetes, enhances flipper flexibility for steering and stability during high-speed swimming, though it is less extensive than in extinct aquatic reptiles like ichthyosaurs, where all digits often show extreme elongation.[103] Digit V in odontocetes shows phalangeal reduction, often to fewer than the plesiomorphic three elements, which contributes to the tapered shape of the flipper trailing edge.[103] Sirenians (manatees and dugongs) possess paddle-like forelimbs with a pentadactylous base, but without hyperphalangy; instead, digits are shortened and broadened, with the first digit notably reduced in size and the fifth enlarged for better surface area in slow, undulating propulsion.[104] Manatees (Trichechus spp.) feature nails on digits II–IV (sometimes three to four per flipper), aiding in tactile foraging on aquatic vegetation, while dugongs (Dugong dugon) lack nails entirely, reflecting their benthic grazing adaptations.[105] Hindlimbs are vestigial or absent, emphasizing tail-powered swimming over limb use. These modifications support a herbivorous, low-speed lifestyle in shallow coastal waters, differing from the high-maneuverability needs of cetaceans.[104] Pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses) display semi-aquatic forelimb adaptations with retained pentadactyly, where digits are elongated and webbed to form flexible flippers capable of both swimming and terrestrial locomotion. In phocid seals (true seals), foreflippers taper distally due to progressive length reduction from digit I to V, with robust, trochleated joints allowing digit spreading and curling for enhanced thrust during undulatory swimming.[106] Otariids (eared seals like sea lions) have longer, more mobile foreflippers with claws (though reduced in size) on all five digits, facilitating prey capture and hauling out on land, while walruses show further modifications with reduced claws and extended cartilaginous tips for sensory and manipulative roles.[107] Unlike cetaceans, pinnipeds lack hyperphalangy, maintaining standard phalangeal counts but with increased overall limb rigidity for alternating forelimb paddling in more versatile aquatic-terrestrial transitions.[106]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dactyly