Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Inbreeding

View on Wikipedia

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically.[1] By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and other consequences that may arise from expression of deleterious recessive traits resulting from incestuous sexual relationships and consanguinity.

Inbreeding results in homozygosity which can increase the chances of offspring being affected by recessive traits.[2] In extreme cases, this usually leads to at least temporarily decreased biological fitness of a population[3][4] (called inbreeding depression), which is its ability to survive and reproduce. An individual who inherits such deleterious traits is colloquially referred to as inbred. The avoidance of expression of such deleterious recessive alleles caused by inbreeding, via inbreeding avoidance mechanisms, is the main selective reason for outcrossing.[5][6] Crossbreeding between populations sometimes has positive effects on fitness-related traits,[7] but also sometimes leads to negative effects known as outbreeding depression. However, increased homozygosity increases the probability of fixing beneficial alleles and also slightly decreases the probability of fixing deleterious alleles in a population.[8] Inbreeding can result in purging of deleterious alleles from a population through purifying selection.[9][10][11]

Inbreeding is a technique used in selective breeding. For example, in livestock breeding, breeders may use inbreeding when trying to establish a new and desirable trait in the stock and for producing distinct families within a breed, but will need to watch for undesirable characteristics in offspring, which can then be eliminated through further selective breeding or culling. Inbreeding also helps to ascertain the type of gene action affecting a trait. Inbreeding is also used to reveal deleterious recessive alleles, which can then be eliminated through assortative breeding or through culling. In plant breeding, inbred lines are used as stocks for the creation of hybrid lines to make use of the effects of heterosis. Inbreeding in plants also occurs naturally in the form of self-pollination.

Inbreeding can significantly influence gene expression which can prevent inbreeding depression.[12]

Overview

[edit]

Offspring of biologically related persons are subject to the possible effects of inbreeding, such as congenital birth defects. The chances of such disorders are increased when the biological parents are more closely related. This is because such pairings have a 25% probability of producing homozygous zygotes, resulting in offspring with two recessive alleles, which can produce disorders when these alleles are deleterious.[13] Because most recessive alleles are rare in populations, it is unlikely that two unrelated partners will both be carriers of the same deleterious allele; however, because close relatives share a large fraction of their alleles, the probability that any such deleterious allele is inherited from the common ancestor through both parents is increased dramatically. For each homozygous recessive individual formed there is an equal chance of producing a homozygous dominant individual — one completely devoid of the harmful allele. Contrary to common belief, inbreeding does not in itself alter allele frequencies, but rather increases the relative proportion of homozygotes to heterozygotes; however, because the increased proportion of deleterious homozygotes exposes the allele to natural selection, in the long run its frequency decreases more rapidly in inbred populations. In the short term, incestuous reproduction is expected to increase the number of spontaneous abortions of zygotes, perinatal deaths, and postnatal offspring with birth defects.[14] The advantages of inbreeding may be the result of a tendency to preserve the structures of alleles interacting at different loci that have been adapted together by a common selective history.[15]

Malformations or harmful traits can stay within a population due to a high homozygosity rate, and this will cause a population to become fixed for certain traits, like having too many bones in an area, like the vertebral column of wolves on Isle Royale or having cranial abnormalities, such as in Northern elephant seals, where their cranial bone length in the lower mandibular tooth row has changed. Having a high homozygosity rate is problematic for a population because it will unmask recessive deleterious alleles generated by mutations, reduce heterozygote advantage, and it is detrimental to the survival of small, endangered animal populations.[16] When deleterious recessive alleles are unmasked due to the increased homozygosity generated by inbreeding, this can cause inbreeding depression.[17]

There may also be other deleterious effects besides those caused by recessive diseases. Thus, similar immune systems may be more vulnerable to infectious diseases (see Major histocompatibility complex and sexual selection).[18]

Inbreeding history of the population should also be considered when discussing the variation in the severity of inbreeding depression between and within species. With persistent inbreeding, there is evidence that shows that inbreeding depression becomes less severe. This is associated with the unmasking and elimination of severely deleterious recessive alleles. However, inbreeding depression is not a temporary phenomenon because this elimination of deleterious recessive alleles will never be complete. Eliminating slightly deleterious mutations through inbreeding under moderate selection is not as effective. Fixation of alleles most likely occurs through Muller's ratchet, when an asexual population's genome accumulates deleterious mutations that are irreversible.[19]

Despite all its disadvantages, inbreeding can also have a variety of advantages, such as ensuring a child produced from the mating contains, and will pass on, a higher percentage of its mother/father's genetics, reducing the recombination load,[20] and allowing the expression of recessive advantageous phenotypes. Some species with a Haplodiploidy mating system depend on the ability to produce sons to mate with as a means of ensuring a mate can be found if no other male is available. It has been proposed that under circumstances when the advantages of inbreeding outweigh the disadvantages, preferential breeding within small groups could be promoted, potentially leading to speciation.[21]

Genetic disorders

[edit]Autosomal recessive disorders occur in individuals who have two copies of an allele for a particular recessive genetic mutation.[22] Except in certain rare circumstances, such as new mutations or uniparental disomy, both parents of an individual with such a disorder will be carriers of the gene. These carriers do not display any signs of the mutation and may be unaware that they carry the mutated gene. Since relatives share a higher proportion of their genes than do unrelated people, it is more likely that related parents will both be carriers of the same recessive allele, and therefore their children are at a higher risk of inheriting an autosomal recessive genetic disorder. The extent to which the risk increases depends on the degree of genetic relationship between the parents; the risk is greater when the parents are close relatives and lower for relationships between more distant relatives, such as second cousins, though still greater than for the general population.[23]

Children of parent-child or sibling-sibling unions are at an increased risk compared to cousin-cousin unions.[24]: 3 Inbreeding may result in a greater than expected phenotypic expression of deleterious recessive alleles within a population.[25] As a result, first-generation inbred individuals are more likely to show physical and health defects,[26][27] including:

- Lower intelligence quotient levels and higher incidence rates of being affected by an intellectual disability

- Reduced fertility both in litter size and sperm viability

- Increased genetic disorders

- Fluctuating facial asymmetry

- Lower birth rate

- Higher infant mortality and child mortality[28]

- Smaller adult size

- Loss of immune system function

- Increased cardiovascular risks[29]

The isolation of a small population for a period of time can lead to inbreeding within that population, resulting in increased genetic relatedness between breeding individuals. Inbreeding depression can also occur in a large population if individuals tend to mate with their relatives, instead of mating randomly.[citation needed]

Due to higher prenatal and postnatal mortality rates, some individuals in the first generation of inbreeding will not live on to reproduce.[30] Over time, with isolation, such as a population bottleneck caused by purposeful (assortative) breeding or natural environmental factors, the deleterious inherited traits are culled.[5][6][31]

Island species are often very inbred, as their isolation from the larger group on a mainland allows natural selection to work on their population. This type of isolation may result in the formation of race or even speciation, as the inbreeding first removes many deleterious genes, and permits the expression of genes that allow a population to adapt to an ecosystem. As the adaptation becomes more pronounced, the new species or race radiates from its entrance into the new space, or dies out if it cannot adapt and, most importantly, reproduce.[32]

The reduced genetic diversity, for example due to a bottleneck will unavoidably increase inbreeding for the entire population. This may mean that a species may not be able to adapt to changes in environmental conditions. Each individual will have similar immune systems, as immune systems are genetically based. When a species becomes endangered, the population may fall below a minimum whereby the forced interbreeding between the remaining animals will result in extinction.[citation needed]

Natural breedings include inbreeding by necessity, and most animals only migrate when necessary. In many cases, the closest available mate is a mother, sister, grandmother, father, brother, or grandfather. In all cases, the environment presents stresses to remove from the population those individuals who cannot survive because of illness.[citation needed]

There was an assumption[by whom?] that wild populations do not inbreed; this is not what is observed in some cases in the wild. However, in species such as horses, animals in wild or feral conditions often drive off the young of both sexes, thought to be a mechanism by which the species instinctively avoids some of the genetic consequences of inbreeding.[33] In general, many mammal species, including humanity's closest primate relatives, avoid close inbreeding possibly due to the deleterious effects.[24]: 6

Examples

[edit]Although there are several examples of inbred populations of wild animals, the negative consequences of this inbreeding are poorly documented.[citation needed] In the South American sea lion, there was concern that recent population crashes would reduce genetic diversity. Historical analysis indicated that a population expansion from just two matrilineal lines was responsible for most of the individuals within the population. Even so, the diversity within the lines allowed great variation in the gene pool that may help to protect the South American sea lion from extinction.[34]

In lions, prides are often followed by related males in bachelor groups. When the dominant male is killed or driven off by one of these bachelors, a father may be replaced by his son. There is no mechanism for preventing inbreeding or to ensure outcrossing. In the prides, most lionesses are related to one another. If there is more than one dominant male, the group of alpha males are usually related. Two lines are then being "line bred". Also, in some populations, such as the Crater lions, it is known that a population bottleneck has occurred. Researchers found far greater genetic heterozygosity than expected.[35] In fact, predators are known for low genetic variance, along with most of the top portion of the trophic levels of an ecosystem.[36] Additionally, the alpha males of two neighboring prides can be from the same litter; one brother may come to acquire leadership over another's pride, and subsequently mate with his 'nieces' or cousins. However, killing another male's cubs, upon the takeover, allows the new selected gene complement of the incoming alpha male to prevail over the previous male. There are genetic assays being scheduled for lions to determine their genetic diversity. The preliminary studies show results inconsistent with the outcrossing paradigm based on individual environments of the studied groups.[35]

In Central California, sea otters were thought to have been driven to extinction due to over hunting, until a small colony was discovered in the Point Sur region in the 1930s.[37] Since then, the population has grown and spread along the central Californian coast to around 2,000 individuals, a level that has remained stable for over a decade. Population growth is limited by the fact that all Californian sea otters are descended from the isolated colony, resulting in inbreeding.[38]

Cheetahs are another example of inbreeding. Thousands of years ago, the cheetah went through a population bottleneck that reduced its population dramatically so the animals that are alive today are all related to one another. A consequence from inbreeding for this species has been high juvenile mortality, low fecundity, and poor breeding success.[39]

In a study on an island population of song sparrows, individuals that were inbred showed significantly lower survival rates than outbred individuals during a severe winter weather related population crash. These studies show that inbreeding depression and ecological factors have an influence on survival.[19]

The Florida panther population was reduced to about 30 animals, so inbreeding became a problem. Several females were imported from Texas and now the population is better off genetically.[40][41]

Measures

[edit]A measure of inbreeding of an individual A is the probability F(A) that both alleles in one locus are derived from the same allele in an ancestor. These two identical alleles that are both derived from a common ancestor are said to be identical by descent. This probability F(A) is called the "coefficient of inbreeding".[42]

Another useful measure that describes the extent to which two individuals are related (say individuals A and B) is their coancestry coefficient f(A,B), which gives the probability that one randomly selected allele from A and another randomly selected allele from B are identical by descent.[43] This is also denoted as the kinship coefficient between A and B.[44]

A particular case is the self-coancestry of individual A with itself, f(A,A), which is the probability that taking one random allele from A and then, independently and with replacement, another random allele also from A, both are identical by descent. Since they can be identical by descent by sampling the same allele or by sampling both alleles that happen to be identical by descent, we have f(A,A) = 1/2 + F(A)/2.[45]

Both the inbreeding and the coancestry coefficients can be defined for specific individuals or as average population values. They can be computed from genealogies or estimated from the population size and its breeding properties, but all methods assume no selection and are limited to neutral alleles.[citation needed]

There are several methods to compute this percentage. The two main ways are the path method[46][42] and the tabular method.[47][48]

Typical coancestries between relatives are as follows:

- Father/daughter or mother/son → 25% (1⁄4)

- Brother/sister → 25% (1⁄4)

- Grandfather/granddaughter or grandmother/grandson → 12.5% (1⁄8)

- Half-brother/half-sister, Double cousins → 12.5% (1⁄8)

- Uncle/niece or aunt/nephew → 12.5% (1⁄8)

- Great-grandfather/great-granddaughter or great-grandmother/great-grandson → 6.25% (1⁄16)

- Half-uncle/niece or half-aunt/nephew → 6.25% (1⁄16)

- First cousins → 6.25% (1⁄16)

Animals

[edit]

Wild animals

[edit]- Banded mongoose females regularly mate with their fathers and brothers.[49]

- Bed bugs: North Carolina State University found that bedbugs, in contrast to most other insects, tolerate incest and are able to genetically withstand the effects of inbreeding quite well.[50]

- Common fruit fly females prefer to mate with their own brothers over unrelated males.[51]

- Cottony cushion scales: 'It turns out that females in these hermaphrodite insects are not really fertilizing their eggs themselves, but instead are having this done by a parasitic tissue that infects them at birth,' says Laura Ross of Oxford University's Department of Zoology. 'It seems that this infectious tissue derives from left-over sperm from their father, who has found a sneaky way of having more children by mating with his daughters.'[52][53]

- Adactylidium: The single male offspring mite mates with all the daughters when they are still in the mother. The females, now impregnated, cut holes in their mother's body so that they can emerge. The male emerges as well, but does not look for food or new mates, and dies after a few hours. The females die at the age of 4 days, when their own offspring eat them alive from the inside.[54]

Domestic animals

[edit]

Breeding in domestic animals is primarily assortative breeding (see selective breeding). Without the sorting of individuals by trait, a breed could not be established, nor could poor genetic material be removed. Homozygosity is the case where similar or identical alleles combine to express a trait that is not otherwise expressed (recessiveness). Inbreeding exposes recessive alleles through increasing homozygosity.[58]

Breeders must avoid breeding from individuals that demonstrate either homozygosity or heterozygosity for disease causing alleles.[59] The goal of preventing the transfer of deleterious alleles may be achieved by reproductive isolation, sterilization, or, in the extreme case, culling. Culling is not strictly necessary if genetics are the only issue in hand. Small animals such as cats and dogs may be sterilized, but in the case of large agricultural animals, such as cattle, culling is usually the only economic option.[citation needed]

The issue of casual breeders who inbreed irresponsibly is discussed in the following quotation on cattle:

Meanwhile, milk production per cow per lactation increased from 17,444 lbs to 25,013 lbs from 1978 to 1998 for the Holstein breed. Mean breeding values for milk of Holstein cows increased by 4,829 lbs during this period.[60] High producing cows are increasingly difficult to breed and are subject to higher health costs than cows of lower genetic merit for production (Cassell, 2001).

Intensive selection for higher yield has increased relationships among animals within breed and increased the rate of casual inbreeding.

Many of the traits that affect profitability in crosses of modern dairy breeds have not been studied in designed experiments. Indeed, all crossbreeding research involving North American breeds and strains is very dated (McAllister, 2001) if it exists at all.[61]

As a result of long-term cooperation between USDA and dairy farmers which led to a revolution in dairy cattle productivity, the United States has since 1992 been the world's largest supplier of dairy bull semen.[62] However, US genomic technology has resulted in the US dairy cattle population becoming "the most inbred it's ever been" and the rate of increase in US national milk yield has tapered off. Efforts are now being made to identify desirable genes in cattle breeds not yet optimized by US dairy breeders in order to apply hybrid vigor to the US dairy cattle population and thus propel US dairy technology to even higher levels of productivity.[citation needed]

The BBC produced two documentaries on dog inbreeding titled Pedigree Dogs Exposed and Pedigree Dogs Exposed: Three Years On that document the negative health consequences of excessive inbreeding.[citation needed]

Linebreeding

[edit]Linebreeding is a form of inbreeding. There is no clear distinction between the two terms, but linebreeding may encompass crosses between individuals and their descendants or two cousins.[57][63] This method can be used to increase a particular animal's contribution to the population.[57] While linebreeding is less likely to cause problems in the first generation than does inbreeding, over time, linebreeding can reduce the genetic diversity of a population and cause problems related to a too-small gene pool that may include an increased prevalence of genetic disorders and inbreeding depression.[64]

Outcrossing

[edit]Outcrossing is where two unrelated individuals are crossed to produce progeny. In outcrossing, unless there is verifiable genetic information, one may find that all individuals are distantly related to an ancient progenitor. If the trait carries throughout a population, all individuals can have this trait. This is called the founder effect. In the well established breeds, that are commonly bred, a large gene pool is present. For example, in 2004, over 18,000 Persian cats were registered.[65] A possibility exists for a complete outcross, if no barriers exist between the individuals to breed. However, it is not always the case, and a form of distant linebreeding occurs. Again it is up to the assortative breeder to know what sort of traits, both positive and negative, exist within the diversity of one breeding. This diversity of genetic expression, within even close relatives, increases the variability and diversity of viable stock.[citation needed]

Laboratory animals

[edit]Systematic inbreeding and maintenance of inbred strains of laboratory mice and rats is of great importance for biomedical research. The inbreeding guarantees a consistent and uniform animal model for experimental purposes and enables genetic studies in congenic and knock-out animals. In order to achieve a mouse strain that is considered inbred, a minimum of 20 sequential generations of sibling matings must occur. With each successive generation of breeding, homozygosity in the entire genome increases, eliminating heterozygous loci. With 20 generations of sibling matings, homozygosity is occurring at roughly 98.7% of all loci in the genome, allowing for these offspring to serve as animal models for genetic studies.[66] The use of inbred strains is also important for genetic studies in animal models, for example to distinguish genetic from environmental effects. The mice that are inbred typically show considerably lower survival rates.[citation needed]

Humans

[edit]

Effects

[edit]Inbreeding increases homozygosity, which can increase the chances of the expression of deleterious or beneficial recessive alleles and therefore has the potential to either decrease or increase the fitness of the offspring. Depending on the rate of inbreeding, natural selection may still be able to eliminate deleterious alleles.[68] With continuous inbreeding, genetic variation is lost and homozygosity is increased, enabling the expression of recessive deleterious alleles in homozygotes. The coefficient of inbreeding, or the degree of inbreeding in an individual, is an estimate of the percent of homozygous alleles in the overall genome.[69] The more biologically related the parents are, the greater the coefficient of inbreeding, since their genomes have many similarities already. This overall homozygosity becomes an issue when there are deleterious recessive alleles in the gene pool of the family.[70] By pairing chromosomes of similar genomes, the chance for these recessive alleles to pair and become homozygous greatly increases, leading to offspring with autosomal recessive disorders.[70] However, these deleterious effects are common for very close relatives but not for those related on the 3rd cousin or greater level, who exhibit increased fitness.[71]

Inbreeding is especially problematic in small populations where the genetic variation is already limited.[72] By inbreeding, individuals are further decreasing genetic variation by increasing homozygosity in the genomes of their offspring.[73] Thus, the likelihood of deleterious recessive alleles to pair is significantly higher in a small inbreeding population than in a larger inbreeding population.[72]

The fitness consequences of consanguineous mating have been studied since their scientific recognition by Charles Darwin in 1839.[74][75] Some of the most harmful effects known from such breeding includes its effects on the mortality rate as well as on the general health of the offspring.[76] Since the 1960s, there have been many studies to support such debilitating effects on the human organism.[73][74][76][77][78] Specifically, inbreeding has been found to decrease fertility as a direct result of increasing homozygosity of deleterious recessive alleles.[78][79] Fetuses produced by inbreeding also face a greater risk of spontaneous abortions due to inherent complications in development.[80] Among mothers who experience stillbirths and early infant deaths, those that are inbreeding have a significantly higher chance of reaching repeated results with future offspring.[81] Additionally, consanguineous parents possess a high risk of premature birth and producing underweight and undersized infants.[82] Viable inbred offspring are also likely to be inflicted with physical deformities and genetically inherited diseases.[69] Studies have confirmed an increase in several genetic disorders due to inbreeding such as blindness, hearing loss, neonatal diabetes, limb malformations, disorders of sex development, schizophrenia and several others.[69][83] Moreover, there is an increased risk for congenital heart disease depending on the inbreeding coefficient (See coefficient of inbreeding) of the offspring, with significant risk accompanied by an F =.125 or higher.[26]

Prevalence

[edit]The general negative outlook and eschewal of inbreeding that is prevalent in the Western world today has roots from over 2000 years ago. Specifically, written documents such as the Bible illustrate that there have been laws and social customs that have called for the abstention from inbreeding. Along with cultural taboos, parental education and awareness of inbreeding consequences have played large roles in minimizing inbreeding frequencies in areas like Europe. That being so, there are less urbanized and less populated regions across the world that have shown continuity in the practice of inbreeding.[citation needed]

The continuity of inbreeding is often either by choice or unavoidably due to the limitations of the geographical area. When by choice, the rate of consanguinity is highly dependent on religion and culture.[72] In the Western world, some Anabaptist groups are highly inbred because they originate from small founder populations that have bred as a closed population.[84]

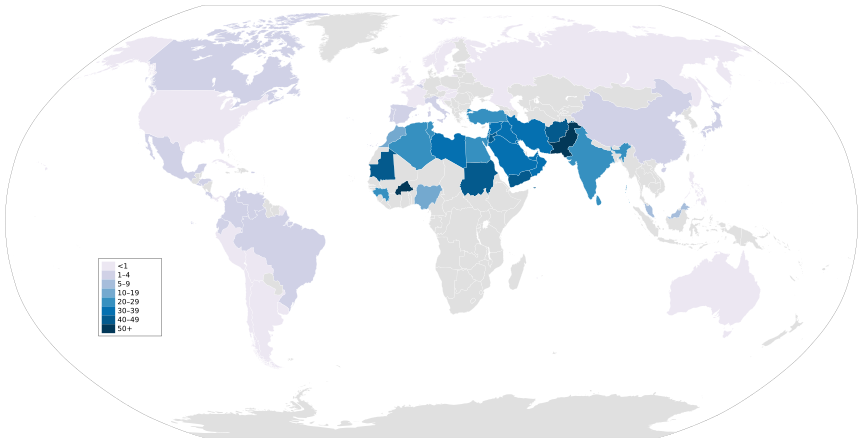

Of the practicing regions, Middle Eastern and northern African nations show the greatest frequencies of consanguinity.[72]

Among these populations with high levels of inbreeding, researchers have found several disorders prevalent among inbred offspring. In Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel, the offspring of consanguineous relationships have an increased risk of congenital malformations, congenital heart defects, congenital hydrocephalus and neural tube defects.[72] Furthermore, among inbred children in Palestine and Lebanon, there is a positive association between consanguinity and reported cleft lip/palate cases.[72] Historically, populations of Qatar have engaged in consanguineous relationships of all kinds, leading to high risk of inheriting genetic diseases. As of 2014, around 5% of the Qatari population suffered from hereditary hearing loss; most were descendants of a consanguineous relationship.[85] In 2017-2019, congenital anomalies due to inbreeding was the most common cause of death of babies belonging to the Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic groups in England and Wales.[86]

Royalty and nobility

[edit]

Inter-nobility marriage was used as a method of forming political alliances among elites. These ties were often sealed only upon the birth of progeny within the arranged marriage. Thus marriage was seen as a union of lines of nobility and not as a contract between individuals.[citation needed]

Royal intermarriage was often practiced among European royal families, usually for interests of state. Over time, due to the relatively limited number of potential consorts, the gene pool of many ruling families grew progressively smaller, until all European royalty was related. This also resulted in many being descended from a certain person through many lines of descent, such as the numerous European royalty and nobility descended from the British Queen Victoria or King Christian IX of Denmark.[87] The House of Habsburg was known for its intermarriages; the Habsburg lip often cited as an ill-effect. The closely related houses of Habsburg, Bourbon, Braganza and Wittelsbach also frequently engaged in first-cousin unions as well as the occasional double-cousin and uncle–niece marriages.[citation needed]

In ancient Egypt, royal women were believed to carry the bloodlines and so it was advantageous for a pharaoh to marry his sister or half-sister;[88] in such cases a special combination between endogamy and polygamy is found. Normally, the old ruler's eldest son and daughter (who could be either siblings or half-siblings) became the new rulers. All rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty uninterruptedly from Ptolemy IV (Ptolemy II married his sister but had no issue) were married to their brothers and sisters, so as to keep the Ptolemaic blood "pure" and to strengthen the line of succession. King Tutankhamun's mother is reported to have been the half-sister to his father,[89] Cleopatra VII (also called Cleopatra VI) and Ptolemy XIII, who married and became co-rulers of ancient Egypt following their father's death, are the most widely known example.[90]

See also

[edit]- Álvarez incest case

- Coefficient of relationship

- Consanguinity

- Cousin marriage

- Cousin marriage in the Middle East

- Evolution of sexual reproduction

- Exogamy

- Founder effect

- F-statistics

- Fritzl case

- Genetic diversity

- Genetic purging

- Genetic sexual attraction

- Heterozygote advantage

- Identical ancestors point

- Inbreeding depression

- Inbreeding in fish

- Incest

- Incest taboo

- Insular dwarfism

- Intellectual inbreeding

- Legality of incest

- List of coupled cousins

- Mahram

- Outbreeding depression

- Outcrossing

- Proximity of blood

- Prohibited degree of kinship

- Selective breeding

- Self-incompatibility in plants (the way that some plants avoid inbreeding)

References

[edit]- ^ Inbreeding at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Nabulsi MM, Tamim H, Sabbagh M, Obeid MY, Yunis KA, Bitar FF (February 2003). "Parental consanguinity and congenital heart malformations in a developing country". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 116A (4): 342–7. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.10020. PMID 12522788. S2CID 44576506.

- ^ Jiménez JA, Hughes KA, Alaks G, Graham L, Lacy RC (October 1994). "An experimental study of inbreeding depression in a natural habitat". Science. 266 (5183): 271–3. Bibcode:1994Sci...266..271J. doi:10.1126/science.7939661. PMID 7939661.

- ^ Chen X (1993). "Comparison of inbreeding and outbreeding in hermaphroditic Arianta arbustorum (L.) (land snail)". Heredity. 71 (5): 456–461. Bibcode:1993Hered..71..456C. doi:10.1038/hdy.1993.163.

- ^ a b Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (September 1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–81. Bibcode:1985Sci...229.1277B. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. PMID 3898363.

- ^ a b Michod RE. Eros and Evolution: A Natural Philosophy of Sex. (1994) Perseus Books, ISBN 0-201-40754-X

- ^ Lynch M (1991). "The Genetic Interpretation of Inbreeding Depression and Outbreeding Depression". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 45 (3). Oregon: Society for the Study of Evolution: 622–629. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb04333.x. PMID 28568822. S2CID 881556.[page needed]

- ^ Whitlock MC (June 2003). "Fixation probability and time in subdivided populations". Genetics. 164 (2): 767–79. doi:10.1093/genetics/164.2.767. PMC 1462574. PMID 12807795.

- ^ Tien NS, Sabelis MW, Egas M (March 2015). "Inbreeding depression and purging in a haplodiploid: gender-related effects". Heredity. 114 (3): 327–32. Bibcode:2015Hered.114..327T. doi:10.1038/hdy.2014.106. PMC 4815584. PMID 25407077.

- ^ Peer K, Taborsky M (February 2005). "Outbreeding depression, but no inbreeding depression in haplodiploid Ambrosia beetles with regular sibling mating". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 59 (2): 317–23. doi:10.1554/04-128. PMID 15807418. S2CID 198156378.

- ^ Gulisija D, Crow JF (May 2007). "Inferring purging from pedigree data". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 61 (5): 1043–51. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00088.x. PMID 17492959. S2CID 24302475.

- ^ García C, Avila V, Quesada H, Caballero A (2012). "Gene-Expression Changes Caused by Inbreeding Protect Against Inbreeding Depression in Drosophila". Genetics. 192 (1): 161–72. doi:10.1534/genetics.112.142687. PMC 3430533. PMID 22714404.

- ^ Livingstone FB (1969). "Genetics, Ecology, and the Origins of Incest and Exogamy". Current Anthropology. 10: 45–62. doi:10.1086/201009. S2CID 84009643.

- ^ Thornhill NW (1993). The Natural History of Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-79854-7.

- ^ Shields, W. M. 1982. Philopatry, Inbreeding, and the Evolution of Sex. Print. 50–69.

- ^ Meagher S, Penn DJ, Potts WK (March 2000). "Male-male competition magnifies inbreeding depression in wild house mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (7): 3324–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.3324M. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.7.3324. PMC 16238. PMID 10716731.

- ^ Swindell WR, et al. (2006). "Selection and Inbreeding Depression: Effects of Inbreeding Rate and Inbreeding Environment". Evolution. 60 (5): 1014–1022. doi:10.1554/05-493.1. PMID 16817541. S2CID 198156086.

- ^ Lieberman D, Tooby J, Cosmides L (April 2003). "Does morality have a biological basis? An empirical test of the factors governing moral sentiments relating to incest". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 270 (1517): 819–26. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2290. PMC 1691313. PMID 12737660.

- ^ a b Pusey A, Wolf M (May 1996). "Inbreeding avoidance in animals". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 11 (5): 201–6. Bibcode:1996TEcoE..11..201P. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10028-8. PMID 21237809.

- ^ Shields WM (1982). Philopatry, inbreeding, and the evolution of sex. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-618-5.

- ^ Joly E (December 2011). "The existence of species rests on a metastable equilibrium between inbreeding and outbreeding. An essay on the close relationship between speciation, inbreeding and recessive mutations". Biology Direct. 6: 62. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-62. PMC 3275546. PMID 22152499.

- ^ Hartl, D.L., Jones, E.W. (2000) Genetics: Analysis of Genes and Genomes. Fifth Edition. Jones and Bartlett Publishers Inc., pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-7637-1511-5.

- ^ Kingston HM (April 1989). "ABC of clinical genetics. Genetics of common disorders". BMJ. 298 (6678): 949–52. doi:10.1136/bmj.298.6678.949. PMC 1836181. PMID 2497870.

- ^ a b Wolf AP, Durham WH, eds. (2005). Inbreeding, incest, and the incest taboo: the state of knowledge at the turn. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5141-4.

- ^ Griffiths AJ, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, Lewontin RC, Gelbart WM (1999). An introduction to genetic analysis. New York: W. H. Freeman. pp. 726–727. ISBN 978-0-7167-3771-1.

- ^ a b Bittles AH, Black ML (January 2010). "Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Consanguinity, human evolution, and complex diseases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 Suppl 1 (suppl 1): 1779–86. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.1779B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906079106. PMC 2868287. PMID 19805052.

- ^ Fareed M, Afzal M (2014). "Evidence of inbreeding depression on height, weight, and body mass index: a population-based child cohort study". American Journal of Human Biology. 26 (6): 784–95. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22599. PMID 25130378. S2CID 6086127.

- ^ Fareed M, Kaisar Ahmad M, Azeem Anwar M, Afzal M (January 2017). "Impact of consanguineous marriages and degrees of inbreeding on fertility, child mortality, secondary sex ratio, selection intensity, and genetic load: a cross-sectional study from Northern India". Pediatric Research. 81 (1): 18–26. doi:10.1038/pr.2016.177. PMID 27632780.

- ^ Fareed M, Afzal M (April 2016). "Increased cardiovascular risks associated with familial inbreeding: a population-based study of adolescent cohort". Annals of Epidemiology. 26 (4): 283–92. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.03.001. PMID 27084548.

- ^ Bittles AH, Grant JC, Shami SA (June 1993). "Consanguinity as a determinant of reproductive behaviour and mortality in Pakistan". International Journal of Epidemiology (Submitted manuscript). 22 (3): 463–7. doi:10.1093/ije/22.3.463. PMID 8359962.

- ^ Kirkpatrick M, Jarne P (February 2000). "The Effects of a Bottleneck on Inbreeding Depression and the Genetic Load". The American Naturalist. 155 (2): 154–167. Bibcode:2000ANat..155..154K. doi:10.1086/303312. PMID 10686158. S2CID 4375158.

- ^ Leck CF (1980). "Establishment of New Population Centers with Changes in Migration Patterns" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 51 (2): 168–173. JSTOR 4512538.

- ^ "ADVS 3910 Wild Horses Behavior", College of Agriculture, Utah State University.

- ^ Freilich S, Hoelzel AR, Choudhury SR. "Genetic diversity and population genetic structure in the South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens)" (PDF). Department of Anthropology and School of Biological & Biomedical Sciences, University of Durham, U.K.

- ^ a b Gilbert DA, Packer C, Pusey AE, Stephens JC, O'Brien SJ (1991-10-01). "Analytical DNA fingerprinting in lions: parentage, genetic diversity, and kinship". The Journal of Heredity. 82 (5): 378–86. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111107. PMID 1940281.

- ^ Ramel C (1998). "Biodiversity and intraspecific genetic variation". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 70 (11): 2079–2084. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.484.8521. doi:10.1351/pac199870112079. S2CID 27867275.

- ^ Kenyon KW (August 1969). "The sea otter in the eastern Pacific Ocean". North American Fauna. 68: 13. Bibcode:1969usgs.rept...13K. doi:10.3996/nafa.68.0001.

- ^ Bodkin JL, Ballachey BE, Cronin MA, Scribner KT (December 1999). "Population Demographics and Genetic Diversity in Remnant and Translocated Populations of Sea Otters". Conservation Biology. 13 (6): 1378–85. Bibcode:1999ConBi..13.1378B. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98124.x. S2CID 86833574.

- ^ Wielebnowski N (1996). "Reassessing the relationship between juvenile mortality and genetic monomorphism in captive cheetahs". Zoo Biology. 15 (4): 353–369. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2361(1996)15:4<353::AID-ZOO1>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ^ UCF report on complex genetic health of Florida panther

- ^ Johnson, Warren E., David P. Onorato, Melody E. Roelke, E. Darrell Land, Mark Cunningham, Robert C. Belden, Roy McBride et al. "Genetic restoration of the Florida panther." Science 329, no. 5999 (2010): 1641-1645.

- ^ a b Wright S (1922). "Coefficients of inbreeding and relationship". American Naturalist. 56 (645): 330–338. Bibcode:1922ANat...56..330W. doi:10.1086/279872. S2CID 83865141.

- ^ Reynolds J, Weir BS, Cockerham CC (November 1983). "Estimation of the coancestry coefficient: basis for a short-term genetic distance". Genetics. 105 (3): 767–79. doi:10.1093/genetics/105.3.767. PMC 1202185. PMID 17246175.

- ^ Casas AM, Igartua E, Valles MP, Molina-Cano JL (November 1998). "Genetic diversity of barley cultivars grown in Spain, estimated by RFLP, similarity and coancestry coefficients". Plant Breeding. 117 (5): 429–35. Bibcode:1998PBree.117..429C. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.1998.tb01968.x. hdl:10261/121301.

- ^ Malecot G. Les Mathématiques de l'hérédité. Paris: Masson et Cie. p. 1048.

- ^ How to compute and inbreeding coefficient (the path method), Braque du Bourbonnais.

- ^ Christensen K. "4.5 Calculation of inbreeding and relationship, the tabular method". Genetic calculation applets and other programs. Genetics pages. Archived from the original on 2010-03-27. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ^ García-Cortés LA, Martínez-Ávila JC, Toro MA (2010-05-16). "Fine decomposition of the inbreeding and the coancestry coefficients by using the tabular method". Conservation Genetics. 11 (5): 1945–52. Bibcode:2010ConG...11.1945G. doi:10.1007/s10592-010-0084-x. S2CID 2636127.

- ^ a b Nichols HJ, Cant MA, Hoffman JI, Sanderson JL (December 2014). "Evidence for frequent incest in a cooperatively breeding mammal". Biology Letters. 10 (12) 20140898. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0898. PMC 4298196. PMID 25540153.

- ^ "Insect Incest Produces Healthy Offspring". 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Loyau A, Cornuau JH, Clobert J, Danchin E (2012). "Incestuous sisters: mate preference for brothers over unrelated males in Drosophila melanogaster". PLOS ONE. 7 (12) e51293. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751293L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051293. PMC 3519633. PMID 23251487.

- ^ Gardner A, Ross L (August 2011). "The evolution of hermaphroditism by an infectious male-derived cell lineage: an inclusive-fitness analysis" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 178 (2): 191–201. Bibcode:2011ANat..178..191G. doi:10.1086/660823. hdl:10023/5096. PMID 21750383. S2CID 15361433.

- ^ "The Evolution of Hermaphroditism by an Infectious Male-Derived Cell Lineage" (PDF). pure.rug.nl. April 26, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2023.

- ^ Freeman S, Herran JC (2007). "Aging and other life history characters". Evolutionary Analysis (4th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-13-227584-2.

- ^ "Polycystic kidney disease | International Cat Care". icatcare.org. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ^ "Polycystic Kidney Disease". www.vet.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ^ a b c Tave D (1999). Inbreeding and brood stock management. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. p. 50. ISBN 978-92-5-104340-0.

- ^ Bosse M, Megens HJ, Derks MF, Cara ÁM, Groenen MA (2019). "Deleterious alleles in the context of domestication, inbreeding, and selection". Evolutionary Applications. 12 (1): 6–17. Bibcode:2019EvApp..12....6B. doi:10.1111/eva.12691. PMC 6304688. PMID 30622631.

- ^ G2036 Culling the Commercial Cow Herd: BIF Fact Sheet, MU Extension Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Extension.missouri.edu. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Genetic Evaluation Results". Archived from the original on August 27, 2001.

- ^ S1008: Genetic Selection and Crossbreeding to Enhance Reproduction and Survival of Dairy Cattle (S-284) Archived 2006-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. Nimss.umd.edu. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ Hutchens J (December 5, 2024). "How big data created the modern dairy cow". Works In Progress. Archived from the original on December 6, 2024. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ Vogt D, Swartz HA, Massey J (October 1993). "Inbreeding: Its Meaning, Uses and Effects on Farm Animals". MU Extension. University of Missouri. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ admin-science (2023-12-20). "Understanding the Genetic Issues Associated with Inbreeding". Genetics. Retrieved 2025-08-31.

- ^ Top Cat Breeds for 2004. Petplace.com. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ Taft, Robert et al. "Know thy mouse." Science Direct. Vol. 22, No. 12, Dec. 2006, pp. 649-653. Trends in Genetics. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.09.010

- ^ Hamamy H (July 2012). "Consanguineous marriages: Preconception consultation in primary health care settings". Journal of Community Genetics. 3 (3): 185–92. doi:10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y. PMC 3419292. PMID 22109912.

- ^ Reed DH, Lowe EH, Briscoe DA, Frankham R (2003-05-01). "Inbreeding and extinction: Effects of rate of inbreeding". Conservation Genetics. 4 (3): 405–410. Bibcode:2003ConG....4..405R. doi:10.1023/A:1024081416729. ISSN 1572-9737.

- ^ a b c Woodley MA (2009). "Inbreeding depression and IQ in a study of 72 countries". Intelligence. 37 (3): 268–276. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2008.10.007.

- ^ a b Kamin LJ (1980). "Inbreeding depression and IQ". Psychological Bulletin. 87 (3): 469–478. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.87.3.469. PMID 7384341.

- ^ de Boer RA, Vega-Trejo R, Kotrschal A, Fitzpatrick JL (July 2021). "Meta-analytic evidence that animals rarely avoid inbreeding". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 5 (7): 949–964. Bibcode:2021NatEE...5..949D. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01453-9. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 33941905. S2CID 233718913.

- ^ a b c d e f Tadmouri GO, Nair P, Obeid T, Al Ali MT, Al Khaja N, Hamamy HA (October 2009). "Consanguinity and reproductive health among Arabs". Reproductive Health. 6 (1) 17. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-6-17. PMC 2765422. PMID 19811666.

- ^ a b Roberts DF (November 1967). "Incest, inbreeding and mental abilities". British Medical Journal. 4 (5575): 336–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5575.336. PMC 1748728. PMID 6053617.

- ^ a b Van Den Berghe PL (2010). "Human inbreeding avoidance: Culture in nature". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 6: 91–102. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00014850. S2CID 146133244.

- ^ Speicher MR, Motulsky AG, Antonarakis SE, Bittles AH, eds. (2010). "Consanguinity, Genetic Drift, and Genetic Diseases in Populations with Reduced Numbers of Founders". Vogel and Motulsky's human genetics problems and approaches (4th ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 507–528. ISBN 978-3-540-37654-5.

- ^ a b Ober C, Hyslop T, Hauck WW (January 1999). "Inbreeding effects on fertility in humans: evidence for reproductive compensation". American Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (1): 225–31. doi:10.1086/302198. PMC 1377721. PMID 9915962.

- ^ Morton NE (August 1978). "Effect of inbreeding on IQ and mental retardation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 75 (8): 3906–8. Bibcode:1978PNAS...75.3906M. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.8.3906. PMC 392897. PMID 279005.

- ^ a b Bittles AH, Grant JC, Sullivan SG, Hussain R (2002-01-01). "Does inbreeding lead to decreased human fertility?". Annals of Human Biology. 29 (2): 111–30. doi:10.1080/03014460110075657. PMID 11874619. S2CID 31317976.

- ^ Ober C, Elias S, Kostyu DD, Hauck WW (January 1992). "Decreased fecundability in Hutterite couples sharing HLA-DR". American Journal of Human Genetics. 50 (1): 6–14. PMC 1682532. PMID 1729895.

- ^ Diamond JM (1987). "Causes of death before birth". Nature. 329 (6139): 487–8. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..487D. doi:10.1038/329487a0. PMID 3657971. S2CID 4338257.

- ^ Stoltenberg C, Magnus P, Skrondal A, Lie RT (April 1999). "Consanguinity and recurrence risk of stillbirth and infant death". American Journal of Public Health. 89 (4): 517–23. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.4.517. PMC 1508879. PMID 10191794.

- ^ Khlat M (December 1989). "Inbreeding effects on fetal growth in Beirut, Lebanon". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 80 (4): 481–4. Bibcode:1989AJPA...80..481K. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330800407. PMID 2603950.

- ^ Bener A, Dafeeah EE, Samson N (December 2012). "Does consanguinity increase the risk of schizophrenia? Study based on primary health care centre visits". Mental Health in Family Medicine. 9 (4): 241–8. PMC 3721918. PMID 24294299.

- ^ Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Tomlin JF (2001). "Towards a Complete North American Anabaptist Genealogy II: Analysis of Inbreeding". Human Biology. 73 (4). Wayne State University Press: 533–545. doi:10.1353/hub.2001.0045. ISSN 0018-7143. JSTOR 41466828. PMID 11512680.

- ^ Girotto G, Mezzavilla M, Abdulhadi K, Vuckovic D, Vozzi D, Khalifa Alkowari M, Gasparini P, Badii R (2014-01-01). "Consanguinity and hereditary hearing loss in Qatar". Human Heredity. 77 (1–4): 175–82. doi:10.1159/000360475. hdl:11577/3455561. PMID 25060281.

- ^ "Births and infant mortality by ethnicity in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 2025-01-27.

- ^ Beeche A (2009). The Gotha: Still a Continental Royal Family, Vol. 1. Richmond, US: Kensington House Books. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-9771961-7-3.

- ^ Seawright C. "Women in Ancient Egypt, Women and Law". thekeep.org. Archived from the original on 2010-12-27. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ^ King Tut Mysteries Solved: Was Disabled, Malarial, and Inbred

- ^ Bevan ER. "The House of Ptolomey". uchicago.edu.

External links

[edit]Inbreeding

View on GrokipediaInbreeding refers to the mating of genetically related individuals, resulting in offspring whose alleles at a given locus are more likely to be identical by descent, thereby increasing homozygosity across the genome.[1] This process elevates the probability of expressing recessive deleterious mutations that are normally masked in heterozygous states, leading to inbreeding depression—a reduction in fitness traits such as survival, fertility, and morphological vigor.[2] In natural populations, inbreeding depression arises primarily from the unmasking of mildly deleterious recessive alleles accumulated in the genome, with empirical evidence from diverse taxa confirming its causal role in diminished reproductive success and increased mortality.[3][4] In humans, consanguineous unions such as first-cousin marriages, which constitute inbreeding at the population level, are associated with measurable health detriments, including elevated risks of congenital malformations, intellectual disabilities, and childhood mortality—effects corroborated by meta-analyses showing excess infant death rates and perinatal complications.[5][6] These outcomes stem from heightened homozygosity, which amplifies the load of rare recessive disorders; for instance, offspring of first cousins exhibit reduced height by approximately 3 cm on average compared to those from unrelated parents, alongside impaired lung function and cognitive performance in adulthood.[7][8] While prevalence varies globally, with higher rates in regions practicing endogamy for cultural or socioeconomic reasons, the genetic costs persist regardless of context, underscoring inbreeding's role in constraining adaptability and elevating disease burden.[5] Historically, extreme inbreeding in isolated elites, such as the Spanish Habsburg dynasty culminating in Charles II (1661–1700), whose pedigree inbreeding coefficient exceeded 0.25, exemplifies severe phenotypic distortions including mandibular prognathism, infertility, and early death, contributing to the dynasty's extinction through compounded fitness declines across generations.[9] In conservation biology, inbreeding threatens small populations by eroding genetic diversity and amplifying extinction risk, as seen in captive breeding programs where deliberate outcrossing mitigates depression effects.[10] Despite occasional purging of highly deleterious alleles in persistently inbred lines, empirical data indicate that recovery remains slow and incomplete without gene flow, affirming inbreeding's net negative impact on long-term viability.[2]

Definition and Biological Foundations

Core Definition

Inbreeding is the mating of genetically related individuals, resulting in offspring with a higher probability of inheriting identical alleles by descent from a common ancestor at any given locus, which elevates genome-wide homozygosity relative to random mating.[11][12] This process occurs across species, including plants, animals, and humans, and contrasts with outbreeding, where mates share no recent common ancestry, preserving heterozygosity.[13] The extent of inbreeding is quantified by the inbreeding coefficient , defined as the probability that two alleles at a locus in an individual are identical by descent, equivalent to the proportion by which heterozygosity is reduced compared to a non-inbred population under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.[14][15] For example, offspring of full siblings have an of 0.25, while first cousins yield an of 0.0625, reflecting the degree of shared ancestry.[10] Inbreeding does not alter allele frequencies directly but redistributes them toward homozygosity, potentially exposing recessive variants.[11] Biologically, inbreeding arises from limited mate choice in small or isolated populations, self-fertilization in plants, or deliberate close-kin pairings in breeding programs, fundamentally driven by pedigree relatedness rather than population-level averages.[13][10]Underlying Genetic Mechanisms

Inbreeding elevates the probability that two alleles at a locus in an offspring are identical by descent (IBD), meaning they are copies of the same ancestral allele received from both parents through recent common ancestry.[16] This probability is quantified by the inbreeding coefficient , which ranges from 0 in outbred individuals to 1 in completely inbred cases, such as self-fertilization or repeated parent-offspring mating.[17] For example, offspring of full siblings have , while first cousins yield .[16] Increased systematically raises genome-wide homozygosity by reducing heterozygosity, as related parents are more likely to carry the same alleles.[18] In genomes harboring deleterious recessive or partially recessive mutations—common due to mutation-selection balance—this homozygosity exposes harmful genotypes that were previously masked in heterozygotes.[19] The resulting decline in viability, fertility, or other fitness traits constitutes inbreeding depression, primarily driven by the cumulative effects of multiple such loci rather than single major genes.[20] The partial dominance hypothesis provides the dominant explanation for this depression: mildly deleterious alleles with small dominance coefficients () confer near-normal fitness when heterozygous but reduce it substantially when homozygous.[21] Genomic studies confirm that homozygosity for strongly or moderately deleterious variants correlates with trait-specific fitness losses, supporting partial dominance over alternatives like overdominance (heterozygote superiority), which lacks comparable empirical backing across taxa.[21][20] In contrast, overdominance contributes minimally, as evidenced by mapping studies showing most depression attributable to recessive effects at identified loci.[22] Purifying selection may purge some deleterious alleles in persistently inbred lineages, potentially mitigating long-term depression, though empirical purging remains inconsistent and context-dependent.[23]Inbreeding Depression and Related Phenomena

Manifestations of Inbreeding Depression

Inbreeding depression manifests as a decline in biological fitness among offspring of closely related individuals, primarily through increased homozygosity that exposes deleterious recessive alleles, leading to reduced performance in traits such as survival, reproduction, and growth across diverse taxa.[24] In wild populations, these effects are evident in moderate to high reductions in fitness components, with inbred matings often resulting in significantly lower viability and fecundity compared to outbred ones.[25] Key manifestations include diminished juvenile survival rates; for instance, in captive wild species across 40 populations, inbred offspring experienced a 33% increase in juvenile mortality.[25] Reproductive output is similarly impaired, as seen in the Scandinavian wolf (Canis lupus) population, where pup inbreeding coefficients correlated strongly with reduced winter litter sizes, decreasing by 1.15 pups per 0.1 unit increase in the inbreeding coefficient (R² = 0.39, p < 0.001).[26] Growth and development suffer as well, with inbred individuals showing slower maturation and smaller body sizes, contributing to overall vigor loss under natural conditions.[25] In plants, inbreeding depression appears across life stages, affecting mating success, embryo production, seed viability, germination, and competitive ability in crowded environments.[27] Experimental studies demonstrate reduced larval growth and population-level competitive performance, with effects varying by species but consistently linked to homozygous deleterious effects.[28] Quantitative meta-analyses indicate median trait declines of 0.13% of the mean per 1% increase in pedigree inbreeding, with stronger impacts on growth metrics like weight (up to 1.071% of standard deviation).[24] These fitness reductions are exacerbated by environmental stresses, amplifying susceptibility to disease, predation, and abiotic challenges, though the magnitude varies by taxon—higher in homeothermic animals (mean δ = 0.509) than poikilotherms (δ = 0.201) or plants (δ = 0.331).[25] In livestock, analogous patterns emerge, with inbreeding linked to higher calf mortality and smaller litter sizes, underscoring conserved mechanisms despite artificial selection.[24]Heterosis and Comparative Evidence

Heterosis, or hybrid vigor, manifests as enhanced biological fitness in offspring from crosses between genetically divergent parents, particularly when compared to inbred parental lines, serving as a counterpoint to inbreeding depression. This superiority arises primarily from increased heterozygosity, which masks deleterious recessive alleles via the dominance hypothesis, though overdominance at certain loci may also contribute. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that hybrid performance exceeds the average or even the better parent in traits like growth, yield, and survival, underscoring the fitness costs of homozygosity accumulation in inbred populations.[29][30] In plants, comparative evidence from controlled crosses highlights heterosis's magnitude. For instance, maize hybrids exhibit grain yield increases of at least 15% over inbred lines, a effect exploited since the 1930s to boost global production, with modern hybrids often surpassing the superior parent by 20% or more under optimal conditions. Similar patterns occur in rice and sorghum, where F1 hybrids show 10-30% improvements in biomass and stress tolerance, directly contrasting yield declines from selfing or sib-mating in inbred progenitors. These quantitative disparities reveal heterosis as a direct offset to inbreeding depression, with hybrid advantages scaling with parental genetic distance up to an optimal point beyond which outbreeding depression may emerge.[31][32] Animal studies provide analogous evidence, particularly in livestock where crossbreeding routinely yields hybrid vigor. In cattle, rotational crossing between breeds can enhance weaning weights by 10-20% and fertility rates, with each 10% increment in heterosis correlating to a 2.3% rise in pregnancy success. Poultry and swine hybrids similarly display 5-15% gains in growth efficiency and viability over purebreds, attributable to reduced homozygous deleterious loads. In wild contexts, heterosis appears in outcrosses between small, inbred populations, such as improved fledging rates in bird genetic rescues, though less pronounced than in domesticated lines due to lower baseline inbreeding. These comparisons affirm that outcrossing restores fitness eroded by inbreeding, with heterosis magnitudes often mirroring depression levels in reverse.[33][34][35]Inbreeding in Natural and Wild Contexts

Patterns in Wild Animal Populations

In wild animal populations, inbreeding levels are generally low due to behavioral mechanisms such as natal dispersal and kin recognition, which promote outbreeding, but they elevate in small, isolated, or socially structured groups where mate choice is constrained.[36] Genetic studies using genomic markers like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) reveal that inbreeding coefficients (F), quantifying homozygosity due to relatedness, typically range from near zero in large continuous habitats to 0.1-0.25 in fragmented or bottlenecked populations.[18] For instance, in cooperatively breeding species with limited dispersal, such as banded mongooses (Mungos mungo) in Ugandan savannas, approximately 10% of pups result from close inbreeding events like brother-sister or father-daughter matings, despite partial avoidance through olfactory kin discrimination.[37][38] Small population sizes and habitat fragmentation exacerbate inbreeding, as seen in endangered large carnivores. Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) exhibit genome-wide inbreeding stemming from Pleistocene bottlenecks around 100,000 and 12,000 years ago, resulting in minimal genetic diversity, with inbreeding coefficients inferred from high homozygosity across loci and manifested in traits like poor semen quality and elevated juvenile mortality.[39][40] Similarly, island or peripheral populations, such as Soay sheep on St. Kilda or rhesus macaques on Cayo Santiago, show elevated F values (up to 0.2) due to founder effects and restricted gene flow, correlating with reduced fitness components like lamb survival.[41] In avian species, close inbreeding (F ≥ 0.25) remains rare, often below 5% of pairings, owing to strong philopatry avoidance and extra-pair copulations that introduce unrelated genes, though it increases in dense or colonial breeders like song sparrows where pedigree analysis detects occasional full-sibling matings linked to lower nestling survival.[42] Rodents and primates in patchy habitats, including kangaroo rats and baboons, display moderate inbreeding in isolated demes, with genomic estimates confirming cumulative effects over generations that heighten vulnerability to environmental stressors without immediate extinction.[41] Overall, while wild populations tolerate episodic inbreeding without collapse, sustained high levels—measured via realized F from parentage assignment—consistently predict inbreeding depression in viability and fecundity, underscoring the role of connectivity in maintaining diversity.[43][44]Natural Avoidance Mechanisms

In wild populations, animals employ multiple behavioral and physiological strategies to minimize inbreeding, thereby preserving genetic diversity and mitigating inbreeding depression. These mechanisms often operate redundantly, with evidence from longitudinal field studies indicating that their combined effect substantially reduces realized inbreeding rates, even in high-density or kin-structured groups. For example, in cooperatively breeding species like meerkats and banded mongooses, inbreeding avoidance through complementary tactics has been shown to lower close-kin matings by up to 40% compared to random expectations.[45][46] Dispersal serves as a foundational pre-mating barrier, typically involving sex-biased natal dispersal where one sex—often males in mammals or females in birds—emigrates from the family group to unrelated territories, limiting opportunities for incest. This pattern is widespread across taxa; in a study of wild birds like the collared flycatcher, longer dispersal distances correlated with reduced inbreeding coefficients, suggesting dispersal evolves primarily to avert mating with retained relatives. In primates such as chimpanzees, both sexes partially disperse, but females more frequently, resulting in lower kinship in breeding units and fewer observed close-kin copulations. Empirical data from marked populations confirm that dispersal failures lead to elevated inbreeding, underscoring its causal role in outbreeding promotion.[47][36][48] Kin recognition enables fine-tuned avoidance during mate encounters, relying on cues like olfactory profiles shaped by familiarity or self-referential phenotype matching. In wild birds such as European storm-petrels, females discriminate kin via odor, preferentially approaching non-kin males in choice assays, which reduces incest risk in philopatric populations. Primates exhibit asymmetrical recognition, avoiding maternal kin more effectively than paternal kin due to prolonged maternal association, as documented in detailed behavioral observations of wild lemurs where encounter rates with kin did not translate to matings owing to rejection behaviors. Insects like the cockroach Blattella germanica similarly use chemical cues for kin discrimination, with females rejecting familiar siblings, demonstrating the mechanism's antiquity across phyla.[49][50][51] MHC-disassortative mate choice provides a genetic proxy for broader outbreeding, as individuals preferentially select partners with dissimilar alleles at major histocompatibility complex loci, which detect pathogens and whose heterozygosity resists inbreeding depression. In mice, early experiments with congenic strains revealed females avoiding MHC-identical males, yielding offspring with enhanced immune diversity; similar patterns hold in wild primates, where MHC divergence predicts mating success independent of pedigree relatedness. Field data from solitary primates like mouse lemurs confirm deviations from random MHC pairing, driven by functional loci like DRB, linking this preference to reduced homozygosity. While not infallible—especially under kin-biased group structures—this mechanism complements dispersal by filtering residual inbreeding opportunities.[52][53][54] Post-copulatory safeguards, such as biased sperm usage or embryonic rejection of homozygous zygotes, act as fail-safes when pre-mating barriers fail, though their efficacy varies; in some mammals, cryptic female choice favors non-kin gametes, but quantification remains challenging without genetic paternity assays. Overall, these mechanisms' prevalence reflects natural selection against inbreeding costs, with lapses occurring mainly in fragmented habitats or small populations where options dwindle.[45][36]Inbreeding in Controlled Breeding

Applications in Domestic Animals

In domestic animal breeding, controlled inbreeding is applied to concentrate desirable genetic traits from elite ancestors, promoting breed uniformity and increasing the likelihood of offspring inheriting specific phenotypes such as conformation, productivity, or temperament.[13] This practice, often through linebreeding—mating relatives sharing one or more common ancestors—allows breeders to exploit prepotency, where superior individuals consistently transmit traits to progeny, facilitating the development of standardized breeds.[55] For instance, in purebred dogs, closed registries enforce inbreeding to maintain morphological standards, resulting in average inbreeding coefficients equivalent to 25% across 227 breeds, akin to full sibling mating.[56] In livestock such as cattle, inbreeding is utilized in sire lines to accelerate genetic progress for traits like milk yield or growth rate, though typically managed to limit coefficients below levels causing severe depression, with pedigree-based averages around 1.6% in large populations like Nelore cattle.[57] Beef cattle breeders employ linebreeding to perpetuate bloodlines of influential bulls, aiming for consistent carcass quality and fertility, while monitoring inbreeding to avoid exceeding 12.5%, beyond which depression in viability intensifies disproportionately.[58] Similarly, in swine and poultry production, initial inbreeding creates homozygous lines for subsequent hybrid vigor through outcrossing, enhancing overall herd performance despite reduced fitness in inbred parental stocks.[55] Companion animals like cats exemplify selective inbreeding for aesthetic traits; breeds such as Persians are developed through repeated close matings to fix silver shading or brachycephalic features, though this elevates risks of polycystic kidney disease and respiratory issues due to heightened homozygosity.[13] In horses, thoroughbred racing lines incorporate controlled inbreeding to preserve speed-related genetics, with coefficients tracked via pedigrees to balance trait fixation against fertility declines observed above 10% inbreeding.[59] These applications underscore inbreeding's role in rapid trait consolidation in closed populations, predicated on the causal increase in homozygosity that amplifies both targeted alleles and latent deleterious recessives, necessitating vigilant outcrossing to sustain long-term viability.[60]Use in Laboratory Settings

In laboratory settings, inbreeding is systematically applied to produce genetically homogeneous strains of model organisms, enabling researchers to control for genetic variability and achieve reproducible results in experiments. This process typically involves at least 20 consecutive generations of controlled matings, such as brother-sister or parent-offspring pairings, which progressively increase homozygosity across the genome until individuals within a strain are nearly identical at virtually all loci, except for sex chromosomes.[61][62] Such uniformity minimizes confounding genetic noise, allowing precise attribution of phenotypic outcomes to specific experimental variables like gene knockouts or environmental manipulations.[62] In rodents, particularly mice, inbred strains dominate biomedical research; for instance, the C57BL/6J strain, originating from matings initiated in 1921 by Clarence Cook Little, has been foundational for studies in cancer genetics, immunology, and metabolic disorders, contributing to discoveries like the BRAF mutation's role in melanoma and the development of targeted therapies such as vemurafenib, approved by the FDA in 2011.[63] These strains support applications in quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping, disease modeling, and preclinical drug testing, where genetic consistency enhances statistical power and reduces the number of animals required, aligning with ethical principles of experimental reduction.[63][62] Similar techniques extend to invertebrates like Drosophila melanogaster, where recombinant inbred lines derived from wild crosses facilitate dissection of polygenic traits and behavioral genetics, as demonstrated in panels mapping aggression and locomotion loci.[64] In fish models such as zebrafish (Danio rerio), inbreeding generates strains like the M-AB line, established through sequential sib-pair matings to yield uniform cohorts for developmental biology and toxicology research, with reduced heterozygosity enabling reliable assessment of gene functions and pollutant effects.[65] Despite potential inbreeding depression—manifesting as lowered viability in early generations—viable strains are maintained via selective breeding, purging deleterious recessives and stabilizing phenotypes for long-term use in fields including neurobehavior and endocrinology.[65][62] Overall, these practices underscore inbreeding's utility in isolating causal genetic mechanisms, though ongoing genetic monitoring is essential to mitigate drift and substrain divergence over time.[61]Techniques like Linebreeding and Outcrossing

Linebreeding constitutes a deliberate, mild form of inbreeding in controlled breeding programs, wherein mates are selected based on their descent from a particular superior ancestor to intensify transmission of favorable alleles while constraining overall relatedness.[13] This technique typically involves pairings such as half-siblings (inbreeding coefficient F ≈ 0.125) or cousins (F ≈ 0.0625), avoiding closer unions like full siblings (F = 0.25) to temper homozygosity buildup.[66] In cattle breeding, for instance, half-brother to half-sister matings have fixed traits like intramuscular fat deposition in Wagyu lines, where some populations exhibit average inbreeding coefficients of 21.7%, amplifying both targeted gains and latent risks of recessive defects.[66] The primary goal of linebreeding is to enhance prepotency—uniform expression of elite traits in progeny—facilitated by elevated genetic uniformity, as quantified by maintaining an ancestor's contribution at or below 50% in descendants to curb excessive inbreeding depression.[13] Empirical assessments in swine reveal performance declines, such as 0.20–0.44 fewer pigs per litter for every 10% rise in inbreeding, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring via pedigree analysis or progeny testing (e.g., 35+ daughter evaluations in dairy cattle at p=0.01 for recessive detection).[13] Despite these controls, linebreeding elevates homozygosity over generations, potentially unmasking deleterious recessives and necessitating periodic genetic audits. Outcrossing, conversely, entails mating animals with negligible shared ancestry within the same breed (relationship coefficient ≈ 0), injecting novel alleles to restore heterozygosity and alleviate inbreeding-induced vigor loss.[13] This strategy mitigates accumulated homozygosity by promoting hybrid-like heterosis without breed hybridization, yielding measurable uplifts in fitness metrics like survival or productivity, as in swine where outcross litters offset prior inbreeding penalties.[13] In pedigree dogs, outcrossing demonstrably curtails inbreeding coefficients and associated maladies, though efficacy wanes in tightly closed registries without sustained donor infusions, highlighting management imperatives for long-term diversity.[67] Breeders often integrate linebreeding and outcrossing cyclically: intensive linebreeding to consolidate traits, followed by strategic outcrosses to dilute inbreeding loads, thereby balancing fixation against depression in populations like livestock or show animals.[13] Genomic tools now refine these approaches, enabling precise kinship tracking to sustain effective population sizes above critical thresholds (e.g., Ne > 50–100) for viability.[68]Inbreeding in Human Societies

Historical Practices Among Elites

Historical elites across civilizations practiced consanguineous marriages, including sibling and uncle-niece unions, primarily to preserve dynastic power, consolidate wealth, and maintain the perceived purity of ruling bloodlines believed to confer divine or superior status. In ancient Egypt, pharaohs from the 18th Dynasty onward, such as Akhenaten (r. 1353–1336 BCE), married full sisters to emulate godly unions and prevent external claims to the throne, a custom extending to priests and nobility.[69] This resulted in reduced height variation among royal mummies compared to commoners, indicating sustained inbreeding over generations.[70] The Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt (305–30 BCE), founded by Ptolemy I Soter, adopted sibling marriages to legitimize Hellenistic rule by mimicking native pharaonic traditions; Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 285–246 BCE) wed his sister Arsinoë II, establishing the practice that continued through Cleopatra VII's unions with brothers Ptolemy XIII and XIV.[71] Such endogamy reinforced intra-family alliances amid succession struggles, though it concentrated deleterious traits without evident purging.[72] In Europe, the Habsburg dynasty exemplified intensive inbreeding from the 15th to 17th centuries to secure territorial control through uncle-niece and double-cousin marriages, as seen in the Spanish branch where Philip II (r. 1556–1598) wed his niece Anna of Austria.[73] This culminated in Charles II of Spain (r. 1665–1700), whose inbreeding coefficient reached 0.254—equivalent to sibling offspring—due to six generations of close-kin unions, rendering him infertile and contributing to the dynasty's extinction upon his death without heirs.[74][75] Empirical analysis confirms inbreeding depression reduced survival rates in Habsburg progeny by up to 20% compared to outbred baselines.[73] These practices prioritized political consolidation over genetic diversity, often yielding frail rulers despite short-term gains in sovereignty.Contemporary Prevalence and Regional Variations

Consanguineous marriages, typically involving first or second cousins, account for approximately 10.4% of unions globally, affecting over 1 billion people in regions where such practices are customary.[76] These rates translate to a mean population inbreeding coefficient (F) of about 0.0117, with first-cousin unions comprising the majority.[77] Prevalence varies sharply by geography and ethnicity, driven by cultural, religious, and socioeconomic factors rather than legal prohibitions, as cousin marriage remains permitted in most countries except a few Western states.[78] In the Middle East and North Africa, rates often exceed 20-50%, with Saudi Arabia reporting around 50-67% of marriages as consanguineous, predominantly first cousins, though urban areas show slight declines from historical peaks.[78] [79] Pakistan exhibits among the highest figures at 60-70%, linked to tribal and kinship structures, while in Jordan and Qatar, rates hover between 50-58%.[80] South Asia, including parts of India and Bangladesh, sees 20-40% in certain communities, often tied to caste endogamy.[78] Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Central Asia report 10-30%, influenced by pastoralist traditions, whereas East Asia and the Americas maintain rates below 1%, reflecting broader exogamy norms and modernization.[78] In Europe and North America, overall prevalence is under 0.5%, but elevated in diaspora populations, such as Pakistani communities in the UK where rates can reach 50-55%.[78] Recent data indicate gradual declines in some areas, for instance, Turkey's first-cousin marriages dropping from 5.9% in 2010 to 3.2% by 2023, attributed to increased education and urbanization eroding traditional preferences.[78] Despite awareness of genetic risks—recognized by 73-85% in surveyed Middle Eastern cohorts—cultural persistence sustains higher rates in endemic regions.[81] [82]Physical and Cognitive Health Consequences