Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isogonal figure

View on WikipediaIn geometry, a polytope (e.g. a polygon or polyhedron) or a tiling is isogonal or vertex-transitive if all its vertices are equivalent under the symmetries of the figure. This implies that each vertex is surrounded by the same kinds of face in the same or reverse order, and with the same angles between corresponding faces.

Technically, one says that for any two vertices there exists a symmetry of the polytope mapping the first isometrically onto the second. Other ways of saying this are that the group of automorphisms of the polytope acts transitively on its vertices, or that the vertices lie within a single symmetry orbit.

All vertices of a finite n-dimensional isogonal figure exist on an (n−1)-sphere.[1]

The term isogonal has long been used for polyhedra. Vertex-transitive is a synonym borrowed from modern ideas such as symmetry groups and graph theory.

The pseudorhombicuboctahedron – which is not isogonal – demonstrates that simply asserting that "all vertices look the same" is not as restrictive as the definition used here, which involves the group of isometries preserving the polyhedron or tiling.

Isogonal polygons and apeirogons

[edit]| Isogonal apeirogons |

|---|

|

| Isogonal skew apeirogons |

All regular polygons, apeirogons and regular star polygons are isogonal. The dual of an isogonal polygon is an isotoxal polygon.

Some even-sided polygons and apeirogons which alternate two edge lengths, for example a rectangle, are isogonal.

All planar isogonal 2n-gons have dihedral symmetry (Dn, n = 2, 3, ...) with reflection lines across the mid-edge points.

| D2 | D3 | D4 | D7 |

|---|---|---|---|

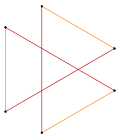

Isogonal rectangles and crossed rectangles sharing the same vertex arrangement |

Isogonal hexagram with 6 identical vertices and 2 edge lengths.[2] |

Isogonal convex octagon with blue and red radial lines of reflection |

Isogonal "star" tetradecagon with one vertex type, and two edge types[3] |

Isogonal polyhedra and 2D tilings

[edit]

|

| Distorted square tiling |

|

| A distorted truncated square tiling |

An isogonal polyhedron and 2D tiling has a single kind of vertex. An isogonal polyhedron with all regular faces is also a uniform polyhedron and can be represented by a vertex configuration notation sequencing the faces around each vertex. Geometrically distorted variations of uniform polyhedra and tilings can also be given the vertex configuration.

| D3d, order 12 | Th, order 24 | Oh, order 48 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.4.6 | 3.4.4.4 | 4.6.8 | 3.8.8 |

A distorted hexagonal prism (ditrigonal trapezoprism) |

A distorted rhombicuboctahedron |

A shallow truncated cuboctahedron |

A hyper-truncated cube |

Isogonal polyhedra and 2D tilings may be further classified:

- Regular if it is also isohedral (face-transitive) and isotoxal (edge-transitive); this implies that every face is the same kind of regular polygon.

- Quasi-regular if it is also isotoxal (edge-transitive) but not isohedral (face-transitive).

- Semi-regular if every face is a regular polygon but it is not isohedral (face-transitive) or isotoxal (edge-transitive). (Definition varies among authors; e.g. some exclude solids with dihedral symmetry, or nonconvex solids.)

- Uniform if every face is a regular polygon, i.e. it is regular, quasiregular or semi-regular.

- Semi-uniform if its elements are also isogonal but allow for multiple edges lengths

- Scaliform if all the edges are the same length.

- Noble if it is also isohedral (face-transitive).

N dimensions: Isogonal polytopes and tessellations

[edit]These definitions can be extended to higher-dimensional polytopes and tessellations. All uniform polytopes are isogonal, for example, the uniform 4-polytopes and convex uniform honeycombs.

The dual of an isogonal polytope is an isohedral figure, which is transitive on its facets.

k-isogonal and k-uniform figures

[edit]A polytope or tiling may be called k-isogonal if its vertices form k transitivity classes. A more restrictive term, k-uniform is defined as a k-isogonal figure constructed only from regular polygons. They can be represented visually with colors by different uniform colorings.

This truncated rhombic dodecahedron is 2-isogonal because it contains two transitivity classes of vertices. This polyhedron is made of squares and flattened hexagons. |

This demiregular tiling is also 2-isogonal (and 2-uniform). This tiling is made of equilateral triangle and regular hexagonal faces. |

2-isogonal 9/4 enneagram (face of the final stellation of the icosahedron) |

See also

[edit]- Edge-transitive (Isotoxal figure)

- Face-transitive (Isohedral figure)

References

[edit]- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (1997), "Isogonal prismatoids", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 18 (1): 13–52, doi:10.1007/PL00009307, MR 1453440

- ^ Coxeter, The Densities of the Regular Polytopes II, p54-55, "hexagram" vertex figure of h{5/2,5}.

- ^ The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eugène Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics and its History, (1994), Metamorphoses of polygons, Branko Grünbaum, Figure 1. Parameter t=2.0

- Peter R. Cromwell, Polyhedra, Cambridge University Press 1997, ISBN 0-521-55432-2, p. 369 Transitivity

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1987). Tilings and Patterns. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1193-1. (p. 33 k-isogonal tiling, p. 65 k-uniform tilings)

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Vertex-transitive graph". MathWorld.

- Isogonal Kaleidoscopical Polyhedra Vladimir L. Bulatov, Physics Department, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Presented at Mosaic2000, Millennial Open Symposium on the Arts and Interdisciplinary Computing, 21–24 August 2000, Seattle, WA VRML models

- Steven Dutch uses the term k-uniform for enumerating k-isogonal tilings

- List of n-uniform tilings

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Demiregular tessellations". MathWorld. (Also uses term k-uniform for k-isogonal)