Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jap is an English abbreviation of the word "Japanese". In the United States, Japanese Americans have come to find the term offensive because of the internment they suffered during World War II. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Jap was not considered primarily offensive. However, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Japanese declaration of war on the US, the term began to be used derogatorily, as anti-Japanese sentiment increased.[1] During the war, signs using the epithet, with messages such as "No Japs Allowed", were hung in some businesses, with service denied to customers of Japanese descent.[2]

History and etymology

[edit]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest recorded use of Jap as an abbreviation for Japanese dates to 1854, in the diary of Edward Y. McCauley, a member of Commodore Perry’s expedition to Japan: "The Commo: gives a Grand dinner to the Japs on the 27th".[3] An example of benign usage was the previous naming of Boondocks Road in Jefferson County, Texas, originally named Jap Road when it was built in 1905 to honor a popular local rice farmer from Japan.[4]

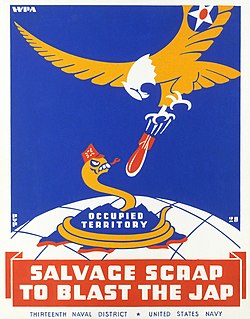

Later popularized during World War II to describe those of Japanese descent, Jap was then commonly used in newspaper headlines to refer to the Japanese and Imperial Japan. Jap began to be used in a derogatory fashion during the war, more so than Nip.[1] Veteran and author Paul Fussell explains the rhetorical usefulness of the word during the war for creating effective propaganda by saying that Japs "was a brisk monosyllable handy for slogans like 'Rap the Jap' or 'Let's Blast the Jap Clean Off the Map'".[1] Some in the United States Marine Corps tried to combine the word Japs with apes to create a new description, Japes, for the Japanese; this neologism never became popular.[1]

In the United States, the term has now been considered derogatory; the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary notes it is "disparaging".[5][6] A snack food company in Chicago named Japps Foods (for the company founder) changed their name and eponymous potato chip brand to Jays Foods shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor to avoid any negative associations with Japan.[7] Spiro Agnew was criticized in the media in 1968 for an offhand remark referring to reporter Gene Oishi as a "fat Jap".[8]

In Texas, under pressure from civil rights groups, Jefferson County commissioners in 2004 decided to drop the name Jap Road from a 4.3-mile (6.9 km) road near the city of Beaumont. In adjacent Orange County, Jap Lane has also been targeted by civil rights groups.[9] The road was originally named for the contributions of Kichimatsu Kishi and the farming colony he founded. In Arizona, the state department of transportation renamed Jap Road near Topock, Arizona to "Bonzai Slough Road" to note the presence of Japanese agricultural workers and family-owned farms along the Colorado River there in the early 20th century. [citation needed] In November 2018, in Kansas, automatically generated license plates which included three digits and "JAP" were recalled after a man of Japanese ancestry saw a plate with that pattern and complained to the state.[10]

Reaction in Japan

[edit]

Koto Matsudaira, Japan's Permanent Representatives to the United Nations, was asked whether he disapproved of the use of the term on a television program in June 1957, and reportedly replied, "Oh, I don't care. It's a [sic] English word. It's maybe American slang. I don't know. If you care, you are free to use it".[11] Matsudaira later received a letter from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL),[12] and apologized for his earlier remarks upon being interviewed by reporters from Honolulu and San Francisco.[13] He then pledged cooperation with the JACL to help eliminate the term Jap from daily use.[14]

In 2003, the Japanese deputy ambassador to the United Nations, Yoshiyuki Motomura, protested the North Korean ambassador's use of the term in retaliation for a Japanese diplomat's use of the term "North Korea" instead of the official name, "Democratic People's Republic of Korea".[15]

In 2011, after the term's offhand use in a March 26 article appearing in The Spectator ("white-coated Jap bloke"), the Minister of the Japanese Embassy in London protested that "most Japanese people find the word 'Japs' offensive, irrespective of the circumstances in which it is used".[16]

Around the world

[edit]Asia & Oceania

[edit]

In Singapore,[17] the term is used relatively frequently as a contraction of the adjective Japanese rather than as a derogatory term. It is also used in Australia, particularly for Japanese cars[18] and Japanese pumpkin.[19]

In New Zealand, the phrase is a non-pejorative contraction of Japanese, although the phrase Jap crap is used to describe poor-quality Japanese vehicles.

Europe

[edit]In the UK, the term is variously seen as neutral or offensive. For instance, Paul McCartney used the term in his 1980 instrumental song "Frozen Jap" from McCartney II, maintaining that he had not intended to cause offense; the song's title was changed to "Frozen Japanese" for the Japanese market.[20] "Nip" is the term that is usually used in the UK when the intention is to cause offence.[21] In Ireland, Jap-Fest is an annual Japanese car show.[22]

Similar to Australian, the analog Swedish word, japsare, is non-pejorative and particularly used for Japanese cars (singular and plural),[23] mirroring the term jänkare ("yankee") for American cars. The plural form japsar ("japs") is commonly used to denote the Japanese collectively, analog to jänkar ("yankees").[24] Guling ("yellow-ian") is the term that is usually used in Sweden when the intention is to be racist. Similarly to Swedish, in Finnish, the term japsi (pronounced /yahpsi/) is frequently used colloquially for anything Japanese, with no derogatory meaning, similar to how the term jenkki ("yank") is used for anything American.[25]

In 1970, the Japanese fashion designer Kenzo Takada opened the Jungle Jap boutique in Paris.[26]

The word Jap is used in Dutch as well, where it is also considered an ethnic slur. It frequently appears in the compound Jappenkampen 'Jap camps', referring to Japanese internment camps for Dutch citizens in the Japanese-occupied Dutch Indies.[27]

North & South America

[edit]In Canada, the term Jap Oranges was once very common, and was not considered derogatory, given the widespread Canadian tradition of eating imported Japanese-grown oranges at Christmas dating back to the 1880s (to the degree that Canada at one time imported by far the bulk of the Japanese orange crop each year), but after WW2 as consumers were still hesitant to purchase products from Japan[28] the term Jap was gradually dropped and they began to be marketed as "Mandarin Oranges". Today the term Jap Oranges is typically only used by older Canadians.[citation needed]

In Brazil, the term japa is sometimes used in place of the standard japonês as a noun and adjective. Its use may be inappropriate in formal contexts.[29] The use of japa in reference to any person of East Asian appearance, regardless of their ancestry, can be pejorative.[30]

See also

[edit]- Nip, a similar slur

- Anti-Japanese sentiment

- Jjokbari (Korean)

- Guizi, Xiao Riben (Chinese)

- List of ethnic slurs

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Paul Fussell, Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 117.

- ^ Gil Asakawa, Nikkeiview: Jap, July 18, 2004.

- ^ "Jap (n.1 & adj.)". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/5975345312. Retrieved 2025-09-01. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.).

- ^ "Tolerance.org: Texas County Bans 'Jap Road'". Archived from the original on September 14, 2005.

- ^ "Jap", Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

- ^ "Oxford Languages | The Home of Language Data". languages.oup.com.

- ^ [1] Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Nation: Fat Jap Trap". Time. February 28, 1972. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Community in Grip of a Kind of Road Rage". September 29, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- ^ Noticias, Univision. "¿Por qué en Kansas están retirando las matrículas de automóviles con las letras JAP?". Univision. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- ^ "Protest envoy acceptance of 'Jap'". Densho. Pacific Citizen. 2 August 1957. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Miyakawa, Wataru (9 July 1957). "Reply to letter regarding use of term "Jap" on a television program". Densho. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Matsudaira sorry on acceptance of 'Jap'". Densho. Pacific Citizen. 9 August 1957. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Matsudaira to cooperate in JACL campaign to depopularize 'Jap'". Densho. Pacific Citizen. 16 August 1957. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Shane Green, Treaty plan could end Korean War, The Age, November 6, 2003

- ^ Ken Okaniwa (9 April 2011). "Not acceptable". The Spectator. Retrieved 22 July 2012. His brief letter continued, noting that the term had been used in the context of the then-recent 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster still-ongoing; "I find the gratuitous use of a word reviled by everyone in Japan utterly inappropriate. I strongly request that you refrain from allowing the use of this term in any future articles that refer to Japan".

- ^ Power up with Jap lunch, The New Paper, 18 May 2006

- ^ "Home". Just Jap. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Growing Jap Pumpkins in Australia: A Comprehensive Guide for Gardeners – Farming How". 16 March 2023.

- ^ PAUL McCARTNEY TALKS McCARTNEY II, SONGWRITING AND MORE! | 1980 Interview, retrieved 2022-08-12

- ^ Vries, Paul de (2022-03-31). "The Welcome Death of a Derogatory Term | JAPAN Forward". japan-forward.com. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ "Homepage". Jap-Fest. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Mest nya japsare på japankvällen". automobilsallskapet.se. 2015-07-23. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ^ "BANZAI!". gamereactor.se. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ^ "Kielitoimiston sanakirja".

- ^ William Wetherall, "Jap, Jappu, and Zyappu, The emotional tapestries of pride and prejudice"[permanent dead link], July 12, 2006.

- ^ Walsum, Sander van (2019-08-14). "'In Japan zijn die Jappenkampen nooit een thema geweest'". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ^ British Columbia Dept. of Agriculture, "Japanese Mandarins" [2] Archived 2013-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, 2008

- ^ "Combinações inusitadas do sushi brasileiro viram tendência até no Japão". www.uol.com.br.

- ^ Hypeness, Redação (July 7, 2017). "Ele desenhou os motivos pelos quais não devemos chamar asiáticos de 'japa' e dizer que são todos iguais". Hypeness. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of jap at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of jap at Wiktionary- Jap in literature

- U.S. Government publication on spotting Japs

Etymology and Early Usage

Linguistic Origins

The term "Jap" originated as a clipped form of "Japanese," a common English-language abbreviation practice for ethnic or national demonyms to achieve linguistic economy in speech and writing.[7] This formation follows patterns seen in other English shortenings, such as "Brit" from "British" or "Scot" from "Scottish," where the initial syllable is retained for brevity without inherent derogatory connotation.[8] The Oxford English Dictionary records the earliest attestation in 1854, in a diary entry by E. Y. McCauley referring to Japanese individuals in a neutral descriptive sense.[8] Subsequent 19th-century uses, such as in American press coverage of the 1860 Japanese embassy to the United States, employed "Jap" descriptively and often complimentarily, as in references to "Jap delegates" or "Jap costumes," indicating no pejorative intent in these initial contexts.[9] Etymological analyses of historical corpora confirm that early instances, including compounds like "Jap lacquer" or "Jap art" by the 1870s, treated the term as a straightforward nominal shortening rather than a term laden with malice or bias.[7] This aligns with broader English abbreviative tendencies driven by phonetic efficiency, as evidenced in dictionary entries predating 20th-century shifts.[8]Pre-20th Century Neutral Applications

The colloquial abbreviation "Jap" for "Japanese" first appeared in English in 1877, serving as a neutral shortening without derogatory intent, analogous to contractions for other nationalities such as "Brit" for British or "Scot" for Scottish.[7] This emergence coincided with heightened Western engagement with Japan after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ended sakoku isolationism and spurred trade, diplomacy, and cultural imports, fostering informal linguistic adaptations based on familiarity rather than animus.[9] In journalism, "Jap" denoted Japanese individuals or artifacts descriptively; for instance, American press coverage of the 1860 Japanese embassy to the United States employed it complimentarily alongside terms like "No-Kamis," reflecting curiosity about the delegation rather than prejudice.[9] Commerce similarly adopted the term benignly, with advertisements promoting "Jap goods" as exotic imports—such as a 1894 notice for celluloid novelties and Jap wares, or a 1895 announcement of a large Pasadena exhibit of Jap goods—highlighting affordability and novelty amid surging imports post-Sino-Japanese War victory in 1895.[10][11] Pre-1900 literature and periodicals, including Harper's New Monthly Magazine in the 1850s–1890s, used "Jap" in factual contexts like expedition accounts or trade discussions, devoid of the scorn that later associations imposed, underscoring its role as a practical descriptor in an era of expanding transpacific exchange.[7][12]Historical Context and Evolution

Pre-World War II Usage

In the early 1900s, the abbreviation "Jap" entered common American English usage primarily as a neutral shorthand for "Japanese," particularly in journalistic coverage of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), where U.S. newspapers frequently employed it to describe Japanese troops, diplomats, and victories without consistent derogatory framing.[13][14] This reflected the era's fascination with Japan's rapid modernization and military prowess, which contrasted with European expectations, though subtle racial undertones appeared in some accounts linking Japanese success to broader "Yellow Peril" anxieties about Asian expansionism.[15] Economic contexts also featured the term descriptively, as in references to "Jap silk" or imports, amid U.S. trade imbalances where Japanese exports like raw silk—comprising over 90% of U.S. supply by 1920—fueled debates on protectionism rather than immediate vilification.[16] By the 1920s and into the 1930s, usage exhibited mixed tones in U.S. media, with neutral applications persisting in factual reporting on Japanese culture, trade, or diplomacy, while derogatory hints emerged in political cartoons and editorials amid heightened Yellow Peril rhetoric portraying Japanese as insidious economic competitors undercutting American labor.[17] For instance, California's agricultural sector saw resentment toward Japanese immigrant farmers, who by 1920 controlled about 10% of truck crops despite comprising less than 2% of the population, prompting nativist campaigns that occasionally infused "Jap" with pejorative implications tied to job displacement fears rather than abstract prejudice.[18] Corpus analyses of printed materials, such as Google Ngram data, reveal low-to-moderate frequency through the 1920s, dominated by descriptive contexts, with acceleration only in the late 1930s correlating to Japan's imperial aggressions in Asia and U.S. embargo responses, underscoring causal links to tangible rivalries over inherent bias.[19] Japanese American figures like attorney Shosuke Sasaki initiated protests against the term's print usage as early as the 1910s, arguing it demeaned immigrants irrespective of intent, though such efforts highlighted a transitional phase where the word's offensiveness was contested rather than universally acknowledged.[4] This gradual evolution—from shorthand amid wartime novelty to a vector for economic grievances—distinguished pre-1930s applications from later wartime dehumanization, driven more by competition in labor markets and trade (e.g., Japanese textile dumping prompting 1930s tariffs) than systemic racism alone.[20]World War II and Emergence as Derogatory Term

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the abbreviation "Jap" proliferated in American wartime media and materials as a shorthand for Japanese forces and civilians, marking its shift toward derogatory connotation amid heightened animosity.[21] This usage surged in propaganda efforts designed to unify public support for the war, appearing in countless posters, cartoons, and advertisements that depicted Japanese people as subhuman threats requiring total defeat.[22] For instance, Dr. Seuss's wartime cartoons frequently employed "Jap" to satirize Japanese aggression, reinforcing racial stereotypes to bolster resolve after early Pacific defeats.[23] The U.S. government, through agencies like the Office of War Information (OWI), systematically endorsed and disseminated such terminology in morale-boosting campaigns from 1942 to 1945, viewing it as an effective tool to demonize the enemy and encourage home-front sacrifices rather than an spontaneous slur emerging from grassroots prejudice.[24] OWI-guided materials, including war bond drives and scrap collection posters, routinely featured phrases like "Slap the Jap with a War Bond" or "You Can't Pop a Jap Without Scrap," linking the term directly to practical war efforts such as funding military operations and recycling resources for armament production.[25] Political speeches and editorials echoed this rhetoric, with "Jap" invoked to evoke the Pearl Harbor betrayal and justify aggressive countermeasures, amplifying its pejorative force through official channels.[26] This orchestrated propaganda correlated with broader wartime policies, including the internment of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066 signed on February 19, 1942, where dehumanizing language like "Jap" in media and government discourse facilitated public acquiescence to mass relocation by framing ethnic Japanese as inherent security risks.[27] However, the term's pre-war neutral applications in trade and journalism underscore that its derogatory emergence was not inevitable but a deliberate product of state-sponsored vilification tied to the 1941-1945 conflict's exigencies, distinguishing it from organic linguistic evolution.[28]Perceptions and Reactions

Japanese Perspectives

In Japan, the term "Jap" is frequently unknown to the general population or regarded as a neutral English abbreviation for "Japanese" rather than a slur. Self-identified native Japanese participants in online forums have expressed perplexity upon learning of its derogatory connotation abroad, with many indicating that it holds no inherent offense domestically. For instance, in a 2024 Reddit thread soliciting direct input from Japanese residents, respondents noted that "in Japan? No. They don’t know it’s a derogatory word" and that it is often perceived simply as a shortened form without negative implications.[29] Others qualified that offensiveness, if any, arises primarily from context rather than the word itself, underscoring a lack of widespread emotional association with wartime dehumanization.[29] Domestic media and public discourse reflect minimal controversy over the term, with no recorded major campaigns or protests akin to those in Japanese-American communities abroad. The absence of prominent references in Japanese-language outlets to "Jap" as a lingering slur aligns with broader societal focus on post-war economic resurgence and pacifism over English-language propaganda relics, diminishing its salience in national memory. This contrasts with imported sensitivities, as English loanwords and abbreviations are tolerated in casual or technical contexts without equivalent scrutiny.[6]American and Western Reactions

In the United States, following World War II, Japanese American advocacy groups such as the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) initiated campaigns to reclassify "Jap" as a derogatory slur and remove it from print media and dictionaries, reflecting broader civil rights efforts to combat ethnic epithets amid declining wartime animosities.[4] These initiatives gained traction in the 1950s, when JACL member Shosuke Sasaki launched a sustained effort targeting major publications and reference works, collaborating with figures like Japan's UN ambassador Koto Matsudaira to pressure for its elimination from common usage. By 1958, the Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary had annotated "Jap" as an expression of contempt and derision, marking a formal acknowledgment of its pejorative status in American lexicography. Media style guides in the U.S. and Western outlets increasingly institutionalized avoidance of the term during the 1960s and beyond, aligning with evolving sensitivities toward ethnic slurs influenced by the civil rights movement, though specific prohibitions varied by publication without a uniform pre-1960s ban.[30] Empirical data on language corpora indicate a sharp post-WWII decline in "Jap"'s frequency in American English texts, dropping to near obsolescence by the late 20th century as wartime contexts faded, even prior to exhaustive advocacy campaigns.[6] This evolution to taboo status, while rooted in legitimate historical grievances, has prompted critiques of overreach, as the term's rarity in contemporary discourse—coupled with its context-dependent origins—suggests institutional lists of slurs may amplify perceived offense beyond current empirical usage patterns.[4]International Variations

In the United Kingdom, "Jap" has historically been regarded as less derogatory than in the United States, with British English speakers preferring "Nip" for explicitly pejorative references to Japanese people during and after World War II.[6] This distinction reflects a milder post-war fade in usage intensity, as evidenced by the term's appearance in British wartime media and literature without the same level of institutional taboo that developed in American contexts.[31] Australian English exhibits further variation, where "Jap" persists among older speakers in references to World War II events, such as invasions or military encounters, without equivalent modern hypersensitivity.[31] The term appears in Australian colloquial lists as a descriptor for persons of Japanese descent, often alongside "Nip," indicating a neutral or contextual shortening rather than inherent slur status.[32] This usage aligns with broader Commonwealth English patterns, where the abbreviation's pejoration tied to U.S.-centric wartime propaganda has not fully permeated local dialects. In non-Anglophone European contexts, perceptions of "Jap" show limited adoption as a slur, given its English origins and the preference for local equivalents during wartime hostilities.[12] Dictionary entries, including those tracing global English variants, document the term's neutral clipping from "Japanese" predating World War II, with international citations varying by regional exposure to Allied propaganda rather than uniform offensiveness.[8] Such relativity underscores that the term's derogatory weight is culturally contingent, diminishing outside North American spheres.Controversies and Debates

Claims of Inherent Offensiveness

Proponents of viewing "Jap" as inherently offensive assert that the term's entrenchment in World War II propaganda, which portrayed Japanese people as subhuman enemies, imparts a permanent derogatory connotation incapable of neutral reclamation.[33][34] This perspective emphasizes the word's role in facilitating dehumanization, such as during the internment of Japanese Americans, where it allegedly stripped individuals of citizenship identity and reduced them to ethnic adversaries.[33] Organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League have condemned recent usages, such as a 2025 reference to an internment site as a "Jap Camp," as perpetuating anti-Japanese slurs tied to this historical trauma.[35] Such claims often draw on personal testimonies from Japanese Americans, who report enduring psychological echoes of wartime racism, with the term evoking exclusion and violence even decades later.[36] Advocates point to its classification in linguistic resources as a racial epithet, arguing that unlike some slurs that have undergone reclamation in in-group contexts, "Jap" remains broadly taboo due to the scale of associated atrocities and lack of cultural rehabilitation.[30][12] These arguments frequently reference inclusion in ethnic slur compilations and mid-20th-century campaigns, like Shosuke Sasaki's 1950s-1970s effort to reclassify it explicitly as a slur in media style guides, underscoring its perceived indelible harm.[4][37]Counterarguments on Context and Hypersensitivity

The designation of "Jap" as an inherently offensive slur overlooks its context-dependent evolution, as the term entered English as a neutral colloquial abbreviation for "Japanese" in 1877, without initial pejorative intent.[7] Linguistic analysis indicates that its derogatory connotation developed primarily through association with World War II hostilities, akin to "Kraut"—a shortening of "sauerkraut" applied to Germans from 1841, which gained slur status during wartime but retains non-offensive uses in culinary or casual references today. Similarly, "Nip," derived from "Nippon," followed a parallel trajectory, intensifying via conflict rather than lexical essence, demonstrating that such terms' sting derives from historical animus, not intrinsic properties. Arguments against hypersensitivity emphasize that equating pre-war neutral abbreviations with perpetual slurs ignores causal realism rooted in specific geopolitical events, such as Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, which fueled propagandistic rhetoric but did not retroactively imbue the word with timeless toxicity.[7] Modern claims of inherent offensiveness, often amplified in academic and media institutions prone to interpretive overreach, parallel reactions to other ethnic nicknames like "Aussie" or "Yank," which some view as benign shortenings despite occasional pejorative misuse; this suggests a pattern where subjective offense trumps empirical usage history.[38] From a free speech perspective, rigidly banning such abbreviations curtails linguistic dynamism, as languages evolve descriptively through communal adoption rather than prescriptive edicts, potentially eroding expressive range without addressing underlying attitudes.[39] Evidence from etymological records shows no primordial malice in "Jap," supporting rebuttals that hypersensitivity, detached from wartime origins, fosters unnecessary linguistic constriction rather than genuine reconciliation.[7]Legal and Media Instances

In 1957, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) launched a nationwide public education campaign aimed at eliminating the use of "Jap" as a reference to individuals of Japanese ancestry, emphasizing its derogatory implications through media outreach and community advocacy rather than litigation.[40] This effort persisted into subsequent decades but did not result in formal lawsuits, reflecting a preference for voluntary compliance over legal enforcement.[41] Media organizations have codified restrictions on the term via style guides to avoid perceived offensiveness. The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage designates "Jap" as pejorative for Japanese people and advises against its use, even when referencing World War II-era attitudes or documents.[42] Similarly, diversity guidelines for journalists recommend avoiding "Jap" as an ethnic shorthand, aligning with broader editorial practices to prioritize neutral descriptors like "Japanese."[43] Legal challenges involving "Jap" have been infrequent and context-specific, typically embedded in broader discrimination claims rather than standalone prohibitions. In workplace harassment suits, such as a 2010 Chevron case where a supervisor called an employee a "stupid Jap," courts and agencies have cited the term as evidence violating federal and state anti-discrimination statutes like Title VII, leading to findings of hostile environments but not term-specific bans.[44] Hawaii's State v. Hoshijo (2003) referenced "Jap" alongside other slurs in analyzing severe emotional impact under employment law, underscoring its role in proving discriminatory intent without establishing it as independently actionable.[45] A 2020 New Zealand Advertising Standards Authority ruling deemed "Jap" in a car ad offensive, upholding a complaint under codes against racial denigration and requiring removal, though enforcement relied on self-regulation rather than penalties.[46] Online media and gaming platforms have seen moderated instances of enforcement, often through content policies treating "Jap" as a slur. In communities like Reddit's Age of Empires 4 subreddit, users reported chat restrictions on "Jap" or "Japanese" in 2021 discussions, with moderators citing offensiveness guidelines, sparking debates over historical shorthand versus sensitivity. Similar warnings occurred in World of Warships forums around 2020 for abbreviating Japanese naval references as "Jap" instead of "IJN," enforced via automated filters and community reports.[47] Despite these measures, informal persistence appears in non-media contexts without legal fallout. In June 2025, Wyoming state representative Clark Stith referred to the Heart Mountain internment site as "Jap camp" during a public group discussion, drawing criticism but no lawsuits or formal sanctions, illustrating limits of enforcement in casual political speech.[48] No significant escalations in legal or media controversies over the term have been documented from 2020 to 2025, with cases remaining isolated to specific harassment or advertising disputes.[49]Contemporary Status

Modern Linguistic Analysis

Modern linguistic analysis of slurs like "Jap" emphasizes pragmatic mechanisms over semantic encoding for their derogatory force. Semantic theories posit that slurs carry inherent negative content, such as stereotypes or attitudes, as part of their literal meaning, akin to presuppositions or conventional implicatures.[50] In contrast, pragmatic accounts argue that slurs share the truth-conditional semantics of their neutral counterparts—"Jap" denoting a Japanese person without descriptive derogation—but acquire offensiveness through the speaker's act of selection and use, signaling endorsement of pejorative associations.[51] A key pragmatic framework is expressive commitment attribution, which replaces traditional implicature models by viewing slur usage as committing the speaker to derogatory expressive attitudes, independent of literal assertion.[52] For "Jap," originally a neutral abbreviation for "Japanese" in early 20th-century English, wartime contexts imbued it with hostile connotations via repeated propagandistic deployment, but the term's core predication remains neutral; derogation arises from the user's pragmatic choice to invoke those historical associations rather than an essential semantic toxicity.[52] This view aligns with causal realism in language use: offensiveness is not an immutable property of the word but emerges from contextual endorsement, allowing reclamation or neutral reference without inherent violation.[53] Corpus-based studies of ethnic slurs broadly support pragmatic desuetude, where reduced frequency correlates with societal norms against derogatory endorsement rather than semantic prohibition. While specific large-scale corpora for "Jap" post-1980 show sparse occurrences, primarily in historical or reclaimed contexts, this decline reflects pragmatic avoidance of expressive commitments tied to mid-20th-century animus, not an intrinsic barrier to mention.[54] Pragmatic theories thus privilege empirical patterns of use over essentialist claims, underscoring that slurs derogate through speaker intent and social uptake, enabling analytical discussion without performative harm.[55]Usage in Pop Culture and Everyday Language

In contemporary media, the term "Jap" surfaces infrequently, primarily in uncensored depictions of historical contexts such as World War II propaganda within documentaries or films, where archival footage retains original language for authenticity. For instance, discussions in academic analyses of Asian representation in pop culture reference its past derogatory use but note its rarity in 2020s productions, with no widespread adoption or backlash tied to new content.[56] Gaming, a key pop culture domain, has featured controversies over Japanese cultural elements—such as in Assassin's Creed Shadows (released March 2025), criticized by Japanese officials for shrine desecration mechanics—but these debates center on representation rather than the term "Jap" itself, underscoring a shift away from linguistic slurs toward broader sensitivity issues.[57][58] In everyday language, usage remains marginal, with limited evidence of neutral self-reference among Japanese diaspora communities. Many Japanese nationals and diaspora members, particularly those less immersed in English-speaking environments, report unfamiliarity with "Jap" as a slur, treating abbreviations of "Japanese" casually without pejorative intent in informal contexts.[59] This lack of recognition contributes to a declining taboo, as the term evokes minimal reflexive offense outside historical awareness circles. Web searches for 2020s incidents reveal no major spikes in everyday controversies or viral usages, indicating subdued presence compared to prior eras.[60]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Australian_English_terms_for_people