Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Canuck

View on Wikipedia

Canuck (/kəˈnʌk/ kə-NUK) is a slang term for a Canadian, though its semantic nuances are manifold.[1] A variety of theories have been postulated for the etymological origins of the term.[2] The term Kanuck is first recorded in 1835 as a Canadianism, originally referring to Dutch Canadians (which included German Canadians) or French Canadians.[2][3] By the 1850s, the spelling with a "C" became predominant.[2] Today, many Canadians and others use Canuck as a mostly affectionate term for any Canadian.[2][4]

Johnny Canuck is a folklore hero who was created as a political cartoon in 1869 and was later re-invented as a Second World War action hero in 1942.[5] The Vancouver Canucks, a professional ice hockey team in the National Hockey League (NHL), has used a version of "Johnny Canuck" as their team logos.[6]

The Canadian military has used the term colloquially for several projects: Operation Canuck, the Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck and the Fleet 80 Canuck.

Captain Canuck is a Canadian comic book superhero who first appeared in Captain Canuck #1 (July 1975).[7] The series was the first successful Canadian comic book since the collapse of the nation's comic book industry following World War II.[8]

Origin

[edit]Historically the etymology was labelled as unclear,[2] with its most likely origins according to the 2017 Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles, 2nd edition being:

- kanata,[9] "village" (see name of Canada)

- Canada + -uc (Algonquian noun suffix)[3]

- Kanaka, derived from the Hawaiian Kanaka.[10]

According to The Etymology of Canuck by Jacob Adler with contributions from Mitford M. Mathews, the word Canuck connects back to the term kanaka, which is defined as someone indigenous to Hawaii.[11] The term spread beginning in the 1800s however, when kanaka acquired a racist connotation, and was used to refer to Polynesians with darker skin tones negatively.[3]

Usage and examples

[edit]Canadians use Canuck as an affectionate or merely descriptive term for their nationality.[12]

If familiar with the term, most citizens of other nations, including the United States, also use it affectionately, though there are individuals who may use it as a derogatory term.

History

[edit]- Canuck also has the derived meanings of a Canadian pony (rare) and a French-Canadian patois[13] (very rare).

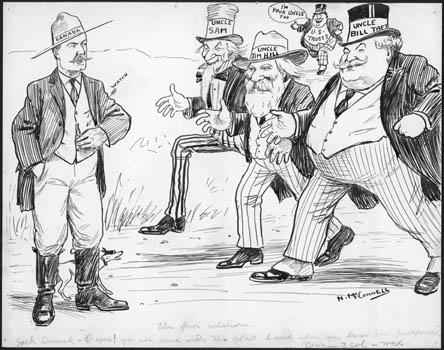

- Johnny Canuck, a personification of Canada who appeared in early political cartoons of the 1860s resisting Uncle Sam's bullying. Johnny Canuck was revived in 1942 by Leo Bachle to defend Canada against the Nazis. The Vancouver Canucks have adopted a personification of Johnny Canuck on their alternate hockey sweater.

- As the historical nickname for three Canadian-built aircraft from the 20th century: the Curtiss JN-4C training biplane, with some 1,260 airframes built; the Avro CF-100 jet fighter; and the Fleet 80 Canuck two-seat side-by-side trainer.

- One of the first uses of Canuck – in the form of Kanuk – specifically referred to Dutch Canadians as well as the French.

- Operation Canuck was the designated name of a British SAS raid led by a Canadian captain, Buck McDonald in January 1945.

- The Canuck letter became a focal point during the US 1972 Democratic primaries, when a letter published in the Manchester Union Leader implied Democratic contender Senator Edmund Muskie was prejudiced against French-Canadians. He soon ended his campaign as a result. The letter was later discovered to have been written by the Nixon campaign in an attempt to sabotage Muskie.

- A brand of firearms engineered and distributed by O'Dell Engineering Ltd since 2014 includes the Canuck 1911, Canuck Over Under and Canuck Shotgun.

Media

[edit]- In the opening of Thornton Wilder's 1938 play Our Town, Polish and "Canuck families" are mentioned as living on the outskirts of the prototypical 1901 New Hampshire town.

- In 1975, in comics by Richard Comely, Captain Canuck is a super-agent for Canadians' security, with Redcoat and Kebec being his sidekicks. (Kebec is claimed to be unrelated to Capitaine Kébec of a French-Canadian comic published two years earlier.) Captain Canuck had enhanced strength and endurance thanks to being bathed in alien rays during a camping trip. The captain was reintroduced in the mid-1990s, and again in 2004.

- The Marvel Comics character Wolverine is often referred to affectionately as "the Ol' Canucklehead" due to his Canadian heritage.

- Soviet Canuckistan was an insult used by Pat Buchanan in response to Canada's reaction to racial profiling by US Customs agents.

Sport

[edit]- The Canada national rugby union team (men's) is officially nicknamed Canucks.

- The Canucks rugby Club, playing in Calgary since 1968.

- The Crazy Canucks, Canadian alpine ski racers who competed successfully on the World Cup circuit in the 1970s.

- The Vancouver Canucks professional ice hockey team, with their former goaltender, Roberto Luongo, having a depiction of Johnny Canuck on his goalie mask.[14] The full body Johnny Canuck was then updated in 2009 by graphic designer Evan Biswanger.

- During the Vancouver 2010 Olympics official Canadian Olympic gear bore the term.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles, Third Edition, s.v. "Canuck", def. (1a)". dchp.arts.ubc.ca. 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Orkin, Mark M. (1970). Speaking Canadian English: An Informal Account of the English Language in Canada. Taylor & Francis. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-317-43632-4.

- ^ a b c Dollinger, Stefan (2006). "Towards a fully revised and extended edition of the Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles (DCHP-2): background, challenges, prospects". HSL/SHL Vol. 6.

- ^ The Mavens' Word of the Day, archived from the original on April 17, 2001

- ^ Bachle, L.; Kulbach, A.; Dak, P. (2015). Johnny Canuck. Comic Syrup Press. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-0-9940547-0-8. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "Canuck". The Canadian Encyclopedia. July 8, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Markstein, Don. "Captain Canuck". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Edwardson, Ryan (November 2003). "The Many Lives of Captain Canuck: Nationalism, Culture, and the creation of a Canadian Comic Book Superhero". The Journal of Popular Culture. 37 (2): 184–201. doi:10.1111/1540-5931.00063.

- ^ Random House Dictionary

- ^ Allen, Irving Lewis (1990). Unkind Words: Ethnic Labeling from Redskin to WASP. pp. 59, 61–62. New York: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-217-8.

- ^ "DCHP-3 | Canuck, definition 1a". dchp.arts.ubc.ca. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Cheng, Pang Guek; Barlas, Robert (2009). CultureShock! Canada: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-981-4435-31-4.

- ^ The Oxford Companion To The English Language

- ^ "Johnny Canuck". Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2009.

External links

[edit]- Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles, Second Edition, UBC, 2017.

- History of the Vancouver Canucks National Hockey League team

- Canuck Unlimited Canadians airplane crews who operated in Southeast Asia during World War II

- Johnny Canuck: with a stamp illustration

- Captain Canuck: with a stamp illustration

- The Word Detective

Canuck

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Proposed Origins

The term "Kanuck" first appears in print in 1835, in Henry Cook Todd's Notes upon Canada and Labrador, where it is used by an American author to refer to Dutch or French Canadians.[4][5] This early attestation indicates an American English origin, initially denoting specific ethnic subgroups within Canada rather than all inhabitants.[4] Several etymological theories have been proposed, though none has achieved consensus due to limited primary linguistic evidence predating 1835. One prominent hypothesis derives "Canuck" from "Canada" through phonetic reduction, akin to informal shortenings like "Can." for the country name, reflecting 19th-century borderland slang.[4] Another theory traces it to the Hawaiian word kanaka, meaning "person" or "human," introduced to North American whalers in the Pacific Northwest around the early 1800s; Polynesian sailors self-identified as kanaka, and the term may have transferred to French-Canadian or other laborers in logging and maritime trades before broadening.[4][5] Less supported suggestions include adaptation from Dutch kanoek or canoek ("canoe"), possibly via early colonial interactions with Indigenous watercraft, or from "Connaught," a nickname applied by French Canadians to Irish immigrants from Ireland's Connacht province.[2] A 1861 article in The Canadian Naturalist and Geologist describes American usage of "Canuck" as "vulgarly and rather contemptuously" applied to Canadians, underscoring its early pejorative tone without resolving its derivation.[4] These theories rely on circumstantial phonetic and historical parallels rather than direct attestation, highlighting the word's uncertain roots amid 19th-century transatlantic and Pacific migrations.[4]Linguistic Evolution

The term "Canuck" evolved in spelling from early variants like "Kanuck" and "Cannuck," with the first documented appearance as "Kanuck" in 1835 referring to a French Canadian. By the mid-19th century, "Canuck" became the predominant form in print, as evidenced in historical dictionaries compiling North American usage. This shift paralleled semantic broadening from primarily denoting French Canadians—often with pejorative undertones in U.S. contexts—to encompassing Anglophone Canadians by 1849, alongside an overall amelioration of derogatory associations within Canada. Rare derived senses included references to the French-Canadian patois or dialect by 1866, and an obsolete American usage for a "Canadian pony" or horse. The pronunciation stabilized early as /kəˈnʌk/, an anglicized rendering that preserved phonetic ties to its informal, ethnic-specific origins among French or working-class Canadian groups, without noted shifts over time. Print media played a key role in standardizing the dominant "Canuck" spelling and neutral semantic shades by the late 19th century, as consistent appearances in newspapers and slang compilations reduced variant forms like "Kanaka."Historical Usage

Early 19th-Century Records

The earliest documented appearance of "Canuck" dates to 1835, when it emerged as a U.S. colloquialism specifically for a French-Canadian, occasionally extended to Canadians of Dutch or German ancestry.[1][6] This initial usage reflected American perceptions of neighboring populations across the border, particularly in frontier regions where economic interactions, such as trade and labor migration, were common. In practical contexts like logging camps along the U.S.-Canada border, the term denoted Canadian workers, often French-speaking, who participated in seasonal lumber operations spanning both sides of the line; records from New England mills indicate its application to these migrants as early as the mid-19th century.[7] American speakers typically employed it in reference to these groups, underscoring cross-border frictions in resource industries without implying broader national identity.[8] The term's tone ranged from neutral descriptor to mild derision in early records; a 1861 geological publication noted its American deployment as "vulgarly and rather contemptuously" toward Canadians generally, highlighting its informal and sometimes dismissive character in scholarly observation.[4] By the late 1860s, "Canuck" began appearing in broader printed media, marking its transition from regional slang to more visible cultural reference, though retaining its American-origin connotation.[9]20th-Century Developments

During the First World War, editorial cartoons increasingly featured Johnny Canuck as a symbol of emerging Canadian autonomy, often depicted alongside figures like Uncle Sam to underscore national contributions such as the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917, which bolstered a sense of distinct identity separate from British imperial ties.[10] This usage in periodicals like newspapers helped propagate resilience amid heavy casualties, with over 60,000 Canadian deaths fostering a collective self-image of hardy settlers defending sovereignty. The term's personification gained prominence in the Second World War, when 16-year-old artist Leo Bachle created Johnny Canuck for Hillborough Studios' Dime Comics #1, released in February 1942, portraying him as an ordinary downed Royal Canadian Air Force pilot turned guerrilla fighter against Nazi forces in occupied Europe.[11] Without superpowers, the character emphasized everyday Canadian grit, appearing in over 20 issues by 1946 to support wartime morale and recruitment, aligning with Canada's mobilization of 1.1 million personnel.[11] Such comics served as subtle propaganda, countering perceptions of Canada as a mere appendage to Allied powers by highlighting independent exploits like the 1945 Operation Canuck raid in Italy.[11] By the mid-20th century, "Canuck" expanded beyond its earlier French-Canadian connotations to denote all Canadians, driven by massive immigration waves—over 1.2 million arrivals between 1901 and 1914, followed by European influxes in the 1920s—that diversified the populace and reinforced a unified national ethos post-wars.[2] This shift reflected causal realities of identity formation: battlefield sacrifices and economic integration diluted ethnic silos, with the term invoked in media to evoke broad patriotism rather than regional divides, as seen in 1940s cartoons asserting cultural resilience against American continentalism.[11]Modern Usage

Within Canada

Within Canada, the term "Canuck" has achieved widespread domestic adoption as a colloquial descriptor for Canadians, particularly among Anglophone populations, and is frequently employed in self-referential contexts without pejorative intent.[2] The Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles, Third Edition (DCHP-3) explicitly notes that, contrary to some external dictionary definitions, Canadians applying "Canuck" to themselves view it as non-derogatory and often affirmative, reflecting semantic amelioration from earlier usages.[2] This normalization is evident in everyday vernacular, where it serves as an informal shorthand akin to other national nicknames, conveying familiarity or mild patriotism rather than offense.[4] Self-identification with "Canuck" appears more prevalent in Western Canada, including British Columbia and Prairie provinces, where regional pride intersects with national identity, though it garners broader acceptance across the country in casual discourse.[4] For instance, it features in community and cultural expressions, such as local sports affiliations or informal groupings that evoke shared Canadian traits, without the negativity sometimes associated abroad.[2] Canadian sources consistently portray its internal usage as affectionate or neutral, with the Canadian Encyclopedia observing that it is "more often wielded with pride" domestically, underscoring a divergence from international connotations.[4] This embrace aligns with linguistic patterns where terms evolve through in-group reclamation, supported by historical Canadian English documentation.[2]International Contexts

In the United States, particularly in the Northeast, "Canuck" has been used as a derogatory slur specifically targeting French Canadians, stemming from waves of Quebecois immigration to industrial areas like New England mills between the 1860s and 1920s, where it connoted lower-class laborers or ethnic outsiders.[3] [12] This pejorative sense persists in some American English dictionaries, which label it as offensive slang for a Canadian, especially a French-speaking one, when employed by non-Canadians.[3] [13] The term's application to English-speaking Canadians is rarer in this context, highlighting its ethnic specificity rather than national breadth.[12] Beyond the U.S., "Canuck" sees limited adoption and lacks the same derogatory weight, appearing infrequently in other English-speaking regions like the United Kingdom or Australia, where it is occasionally recognized as informal slang for any Canadian without strong regional variances.[14] Its international visibility has grown modestly through Canadian cultural exports, such as literature and broadcasting, but remains niche compared to domestic usage, with no evidence of widespread slang integration in non-North American contexts by the 2000s.[15] Linguistic references post-2020, including updated dictionary entries, show no substantive shifts in these international connotations, maintaining the term's primary association with American ethnic derogation while underscoring its obscurity elsewhere.[3] [13]Cultural Representations

Folk Hero Figures

Johnny Canuck emerged in 1869 as a cartoonish folk hero in Canadian political illustrations, depicted as a sturdy lumberjack embodying the resilient, everyday Canadian spirit amid Confederation-era debates.[11] This figure served as a national counterpart to American Uncle Sam or British John Bull, often portrayed outwitting larger adversaries through clever tenacity rather than brute force, reflecting early assertions of Canadian autonomy.[16] By the early 20th century, Johnny Canuck symbolized unpretentious endurance, with appearances in editorial cartoons highlighting resourcefulness in frontier life and resistance to external pressures.[17] During World War II, artist Leo Bachle revived Johnny Canuck in 1941 as a comic book adventurer in Dime Comics, transforming him into a aviator hero combating Nazi threats, which bolstered wartime morale and recruitment efforts in Canada.[18] This iteration emphasized physical prowess and patriotic duty, drawing on the character's foundational traits to project Canadian resolve against global aggression.[19] The evolution underscored a causal link between symbolic archetypes and collective identity formation, as such depictions countered perceptions of Canada as a mere appendage to Allied powers by foregrounding indigenous grit. Captain Canuck debuted in 1975, conceived by Ron Leishman and realized by Richard Comely as an independent superhero in self-published comics, granted enhanced strength by extraterrestrials to defend a futuristic Canada from subversion.[20] Clad in a red-and-white uniform evoking the national flag, the character navigated espionage and internal threats, promoting themes of sovereignty and multiculturalism without overt jingoism.[21] Unlike imported American icons, Captain Canuck's narratives prioritized Canadian agency, contributing to cultural self-assertion during a period of economic dependence on the U.S. and debates over national symbols post-1960s Quiet Revolution influences. These folk heroes played a pivotal role in cultivating Canadian pride by instantiating "Canuck" as a badge of understated fortitude, enabling cultural differentiation from dominant Anglo-American archetypes through serialized tales of self-reliance. Empirical patterns in their depictions—rooted in historical comics rather than elite historiography—reveal how grassroots symbolism reinforced identity resilience against stereotypes of passivity or derivativeness.[22] Their persistence in niche media, despite limited commercial success, evidences a bottom-up causal mechanism for embedding "Canuck" connotations of hardy individualism in public consciousness.Literature and Media

In late 19th-century American fiction, the term "Canuck" frequently referred to French-Canadian immigrants depicted as resilient but rustic laborers in frontier settings. For instance, in William Dean Howells' 1897 novel The Landlord at Lion's Head, a "Canuck" character is shown chopping wood in a New England clearing, embodying the stereotype of hardy, dialect-speaking woodsmen often viewed through an outsider's lens of exotic simplicity. Such portrayals, rooted in real migrations of French-Canadians to U.S. mills and farms during the 1860s–1890s, emphasized physical endurance over cultural nuance, reflecting American authors' tendency to simplify ethnic distinctions without deeper empirical validation of individual agency.[23] Early 20th-century Canadian literature began reclaiming "Canuck" with more affirmative narratives focused on national identity and exploration. Emily Murphy's 1910 memoir Janey Canuck in the West, written under the pseudonym embracing the term, chronicles travels across prairie settlements, portraying Canadians as pioneering settlers adapting to harsh landscapes with pragmatic optimism rather than mere toil.[24] Similarly, Camille Lessard-Bissonnette's 1936 novella Canuck, serialized in a French newspaper, narrates a French-Canadian family's relocation to New England factories, highlighting economic hardships and cultural dislocation through gritty realism drawn from the author's émigré observations, thus shifting focus from stereotype to causal immigrant struggles.[25] In film, "Canuck" appearances often aligned with wartime mobilization, as in the 1942 propaganda feature Captains of the Clouds, where Canadian bush pilots—explicitly termed Canucks—transition to Royal Canadian Air Force roles, showcasing rugged competence in aerial combat to bolster Allied recruitment amid real shortages of trained aviators. Later international media, such as Matthew Rankin's 2019 satirical biopic The Twentieth Century, employs "Canuck" in vignettes critiquing early 20th-century political ambition, exaggerating tropes of innate politeness and moral virtue as naive hindrances to decisive action, though historical records of figures like William Lyon Mackenzie King reveal more calculated pragmatism than such caricatures suggest.[26] These depictions balance rugged individualism with perceived ingenuousness, but overreliance on anecdotal archetypes in media overlooks data from migration patterns and economic records indicating diverse, adaptive responses among Canadians.Sports Associations

Vancouver Canucks NHL Team

The Vancouver Canucks are a professional ice hockey team in the National Hockey League (NHL), based in Vancouver, British Columbia, and competing in the Pacific Division of the Western Conference. The franchise was officially awarded on May 22, 1970, as part of the league's expansion, entering play in the 1970–71 season alongside the Buffalo Sabres. The team's name derives from "Canuck," a longstanding slang term for Canadians that emerged in the 19th century, initially among American frontiersmen and later embraced in British Columbia's whaling and logging communities as a marker of regional identity. This choice reflected the owners' intent to evoke hardy Canadian heritage, distancing from generic names and tying into local folklore like the Johnny Canuck figure.[27][28] Early logos featured abstract designs, evolving to include a stylized hockey-stick-wielding Johnny Canuck in the 1980s and the current orca whale integrated into a "C," symbolizing Pacific Northwest marine life and reinforcing the "Canuck" persona through fan chants like "Go Canucks Go" and third jerseys bearing the folk hero. Fan culture has solidified around this identity, with supporters donning Canuck-themed apparel and participating in rituals that celebrate the term as a badge of provincial pride, particularly during playoff runs that draw packed arenas and widespread viewership.[29] Milestones include the 1982 Stanley Cup Finals, the team's first postseason deep run ending in defeat to the New York Islanders, followed by Game 7 losses in the 1994 Finals to the New York Rangers and 2011 Finals to the Boston Bruins. The 2020s saw a peak in 2023–24 with a Pacific Division title and second-round playoffs, but the 2024–25 season faltered amid injuries and inconsistencies, missing playoffs by six points; entering 2025–26, focus centers on defensive stability and key players like Quinn Hughes for a rebound.[30][31] Through NHL broadcasts reaching tens of millions annually and merchandise sales surging during successes—such as 30–60% increases noted in past playoffs—the Canucks have amplified "Canuck" as a positive, unifying symbol in hockey, embedding it in Canadian sports lexicon via global exposure and local fervor without prior championship validation.[32]