Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

John 5

View on Wikipedia

| John 5 | |

|---|---|

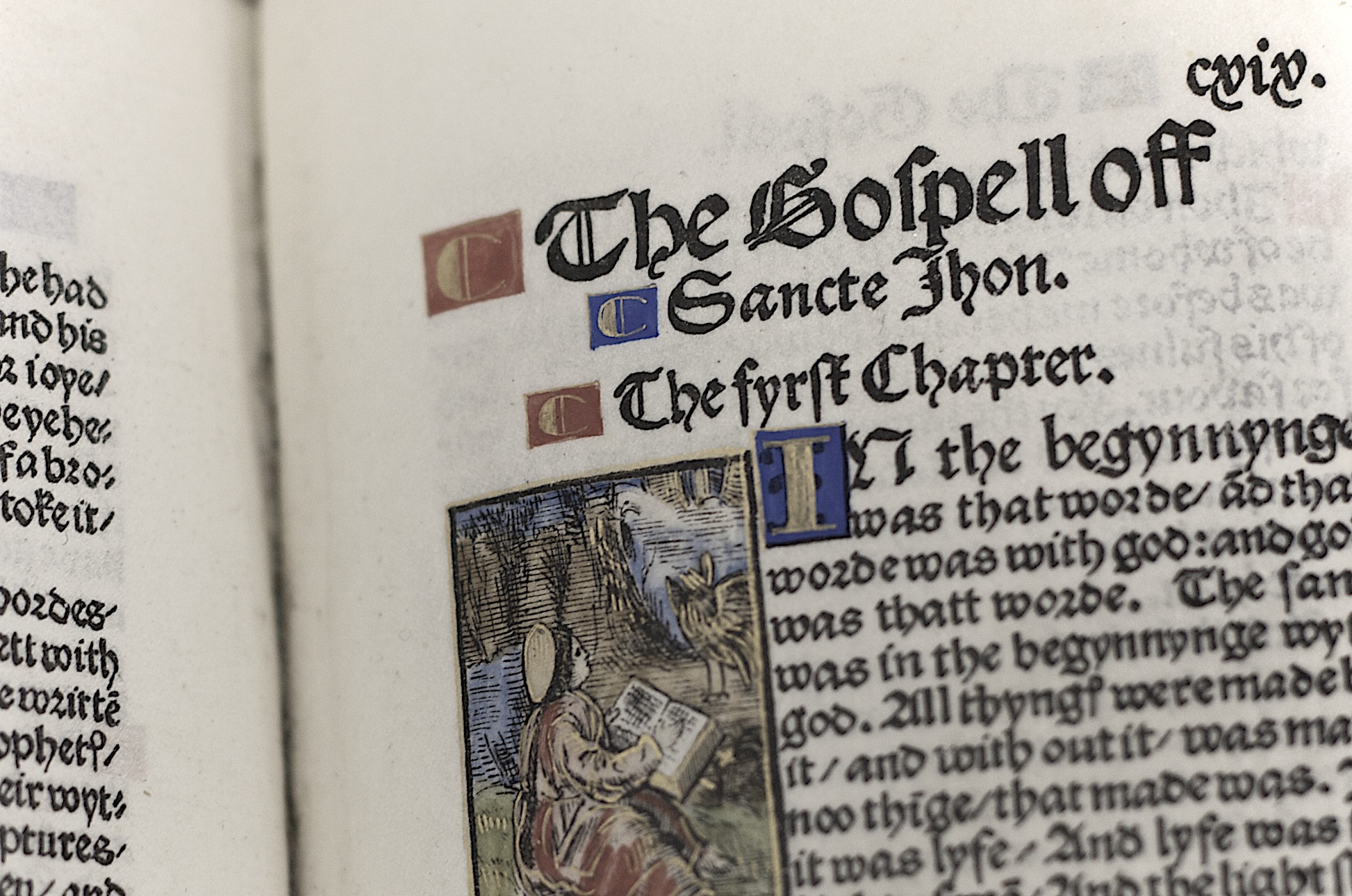

The beginning verses of the Gospel of John chapter 5, from a facsimile edition of William Tyndale's 1525 English translation of the New Testament | |

| Book | Gospel of John |

| Category | Gospel |

| Christian Bible part | New Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 4 |

John 5 is the fifth chapter of the Gospel of John of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It relates Jesus' healing and teaching in Jerusalem, and begins to evidence the hostility shown him by the Jewish authorities.[1]

Text

[edit]

The original text was written in Koine Greek. This chapter is divided into 47 verses.

Textual witnesses

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter are:

- Papyrus 75 (AD 175–225)

- Papyrus 66 (c. 200)

- Papyrus 95 (3rd century; extant verses 26–29, 36–38)[2][3]

- Codex Vaticanus (325–350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330–360)

- Codex Bezae (c. 400)

- Codex Alexandrinus (400–440)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (c. 450; extant verses 1–16)

Some writers place this chapter after John 6.[4]

Old Testament references

[edit]A feast at Jerusalem (verse 1)

[edit]As the chapter opens, Jesus goes again to Jerusalem for "a feast".

According to Deuteronomy 16:16, "Three times a year all your males shall appear before the Lord your God in the place which He chooses (i.e. Jerusalem): at the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Passover), at the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot, or Pentecost), and at the Feast of Tabernacles".[a] John's Gospel records Jesus' visit to Jerusalem for the Passover in John 2:13, and another Passover was mentioned in John 6:4, and so some commentators have speculated whether John 5:1 also referred to a Passover (implying that the events of John 2–6 took place over at least three years), or whether a different feast is indicated. Bengel's Gnomen lists a number of authorities for the proposition that the feast referred to was Pentecost.[6] The Pulpit Commentary notes that "the indefinite Greek: ἑορτη has been identified by commentators with every feast in the calendar, so there can be no final settlement of the problem".[7] In verse 9 it is considered to be a sabbath.[4]

Healing at Bethesda (verses 2-15)

[edit]

At the Pool of Bethesda or Bethzatha,[8] Jesus heals a man who is both paralyzed and isolated. Jesus tells him to "Pick up your mat and walk!" This takes place on the Sabbath, and Jewish religious leaders see the man carrying his mat and tell him this is against the law. He tells them the man who healed him told him to do so, and they ask who that was. He tries to point out Jesus, but he has slipped away into the crowd. Jesus comes to him later and tells him "Sin no more, lest a worse thing come upon you". The man then tells the Jewish religious leaders that it was Jesus who healed him (John 5:15).

The ruins of the Pool of Bethesda are still standing in Jerusalem.

Verses 3b–4

[edit]- In these lay a great multitude of impotent folk, of blind, halt, withered, waiting for the moving of the water. 4 For an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water: whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had. And a certain man was there, which had an infirmity thirty and eight years.[9]

Verses 3b–4, in bold above, are not found in the most reliable manuscripts of John,[10] although they appear in the King James Version of the Bible (which is based on the Textus Receptus). Most modern textual critics believe that John 5:3b–4 is an interpolation, and not an original part of the text of John.[11]

The New English Translation and the English Revised Version omit this text completely, but others, such as the New International Version, refer to it in a note. Bengel, who treats it as integral to the text, thinks that "a certain season" might indicate that the occasion was Pentecost.[6] Biblical commentator Alfred Plummer treats this text as spurious, and argues that the occasions when the water was "moved" or "troubled" (verse 7) came "at irregular intervals".[1]

Verses 9-10

[edit]- 9 And immediately the man was made well, took up his bed, and walked. And that day was the Sabbath. 10 The Jews therefore said to him who was cured, "It is the Sabbath; it is not lawful for you to carry your bed".[12]

Before Jesus is accused of working on the Sabbath, the man he has healed is accused. His bed would probably be only a mat or rug, but Plummer notes that his Jewish accusers "had the letter of the law very strongly on their side",[1] citing several passages in the Mosaic law (Exodus 23:12, Exodus 31:14, Exodus 35:2–3 and Numbers 15:32), but especially Jeremiah 17:21:

- Thus says the Lord: "Take heed to yourselves, and bear no burden on the Sabbath day, nor bring it in by the gates of Jerusalem.

Verse 11

[edit]- He answered them, "He who made me well said to me, 'Take up your bed and walk'."[13]

Plummer notes that the man carries his bed in obedience "to a higher authority",[1] not merely as a practical consequence of his having been cured.

Verse 13

[edit]- Now the man who had been healed did not know who it was, for Jesus had withdrawn, as there was a crowd in the place.[14]

René Kieffer sees Jesus' withdrawal from the drama as purposeful: "in order to allow a discussion to be raised with the man who was healed".[4][b]

Verse 14

[edit]- Afterward Jesus found him in the temple, and said to him, "See, you have been made well. Sin no more, lest a worse thing come upon you."[15]

"Sin no more" is spoken as a prohibition with a present imperative, involving a general condition.[16] The connection expressed between sickness and sin is distinct from Jesus' assertion in John 9:2-3 that the healed man there had not been born blind because of his own sin or his parents'.[4]

Jesus speaks of His Father and the Jews begin to persecute him (verses 16–30)

[edit]The Jews begin to persecute Jesus (and in some texts, verse 16 adds that they "sought to kill him").[17] H. W. Watkins argues that "the words 'and sought to slay Him' should be omitted: in his view they have been inserted in some manuscripts to explain the first clause of John 5:18 (the Jews sought the more to kill him)",[18] the first of several Jewish threats against him (John 7:1, 7:19–25, 8:37, 8:40 and 10:39).[4]

Two reasons emerge:

- firstly, for "working on the Sabbath" (John 5:16);

- secondly, for calling God his "father" and thus making himself equal to God (John 5:18).

From Jesus' words, "My Father", Methodist founder John Wesley observed that "It is evident [that] all the hearers so understood him [to mean] making himself equal with God".[19] St. Augustine sees the words "... equal to God" as an extension of the words in John 1:1: In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.[20]

Jesus continues to speak of himself ("the Son") in relation to God ("the Father"): the Son can do nothing independently of (or in rivalry with) the Father; "the Son can have no separate interest or action from the Father".[21] the Son "acts with no individual self-assertion independent of God, because He is the Son.[1] The Son imitates the Father; the Father loves the Son and shows Him his ways; and the Son gives life in the way that the Father raises the dead. But the Father has delegated the exercise of judgment to the Son: all should honour the Son as they would honour the Father, and anyone who does not honour the Son does not honour the Father who sent Him. (John 5:19–23) The words in verse 19: the Son can do nothing on his own become, in verse 30, I can do nothing on my own; Jesus "identifies himself with the Son".[1]

Two sayings then follow each commencing with a double "amen" (Greek: αμην αμην, translated "Verily, verily" in the King James Version, "Truly, truly" in the English Standard Version, or "Very truly I tell you" in the New International Version):

- He who hears My word and believes in Him who sent Me has everlasting life, and shall not come into judgment, but has passed from death into life. (John 5:24)

- The hour is coming, and now is, when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God; and those who hear will live. (John 5:25)

Reformed Evangelical theologian D. A. Carson sees John 5:24 as giving the "strongest affirmation of inaugurated eschatology in the Fourth Gospel" ... it is not necessary for the believer to "wait until the last day to experience something of resurrection life".[22] Lutheran theologian Heinrich Meyer refers to "the hour when the dead hear the voice of the Son of God" as the "resurrection summons". Meyer argues that this "hour" extends from its beginning at "Christ's entrance upon His life-giving ministry" until "the second advent – already had it begun to be present, but, viewed in its completeness, it still belonged to the future".[23]

The fourfold witness (verses 31–47)

[edit]The final verses of this chapter, verses 31 to 47 refer to what the New King James Version calls the "fourfold witness". Jesus states that he does not bear witness (Greek: η μαρτυρια) to himself, for such witness would not be true or valid. Instead he calls on the testimony of four other witnesses:

- John the Baptist (John 5:33–35)

- Jesus' own works (John 5:36)

- The Father, speaking through the scriptures (John 5:37–40)

- Moses (John 5:45–47).

Jesus says that the Jews who seek to kill him study the scriptures hoping for eternal life, but that the scriptures speak of him, and people still refuse to come to him for life. People accept people who preach in their own name but not in one who comes in the name of the Father. "How can you believe if you accept praise from one another, yet make no effort to obtain the praise that comes from the only God?" He then speaks of Moses as their accuser:

- "But do not think I will accuse you before the Father. Your accuser is Moses, on whom your hopes are set. If you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote about me:

- I will raise up for them a Prophet like you from among their brethren, and will put My words in His mouth, and He shall speak to them all that I command Him" (John 5:45, linked to Deuteronomy 18:18).

But, says Jesus, since you do not believe what Moses wrote, how are you going to believe what I say?" (John 5:47)

Theologian Albert Barnes notes that "the ancient fathers of the Church and the generality of modern commentators have regarded our Lord as the prophet promised in these verses [of Deuteronomy]".[24] Commentators have also explored whether the contrast to be emphasized is a contrast between the person of Moses and the person of Jesus, or between Moses understood as the author of scriptural writings and Jesus, who did not write but whose testimony was his 'sayings'. Bengel's Gnomen argues that in John 5:47, Moses' writings (Greek: Γράμμασιν) are placed in antithesis to Jesus' words (Greek: ῥήμασι): "Often more readily is belief attached to a letter previously received, than to a discourse heard for the first time".[6] However, Plummer is critical of this approach:

- "The emphatic words are 'his' and 'My'. Most readers erroneously emphasize 'writings' and 'words'. The comparison is between Moses and Christ. It was a simple matter of fact that Moses had written[c] and Christ had not: the contrast between writings and words is no part of the argument". The same comparison is seen in Luke 16:31: "If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded though one rose from the dead".[1]

These teachings of Jesus are almost only found in John. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus only speaks of himself as the Messiah in such a straightforward way at the very end, shortly before his death. All this occurs in Jerusalem, while the Synoptic Gospels have very little of Jesus's teachings occurring in Jerusalem and then only shortly before his death.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Plummer, A. (1902), Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on John 5, accessed 11 March 2016

- ^ J. Lenaerts, Un papyrus de l'Évangile de Jean : PL II/31, Chronique d' Egypte 60 (1985), pp. 117–120

- ^ Philip W. Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts. An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textual Criticism, Nashville, Tennessee: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2005, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d e f Kieffer, R., 60. John, in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001), The Oxford Bible Commentary Archived 2 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, p. 969-970

- ^ a b c d "Biblical concordances of John 5 in the 1611 King James Bible".

- ^ a b c Bengel's Gnomon of the New Testament on John 5, accessed on 6 March 2016

- ^ Pulpit Commentary on John 5, accessed 4 March 2016

- ^ Vincent, M., Vincent's Word Studies on John 5: "Tischendorf and Westcott and Hort give βηθζαθά, Bethzatha, House of the Olive".

- ^ John 5:3–5: King James Version (interpolated text bolded)

- ^ Texts lacking this passage include 𝔓66, 𝔓75, א, B, C*, T, and 821

- ^ Craig Blomberg (1997), Jesus and the Gospels, Apollos, pp. 74–75

- ^ John 5:10: NKJV

- ^ John 5:10: NKJV

- ^ John 5:13: English Standard Version

- ^ John 5:14 NKJV

- ^ Note on John 5:14 in the NET Bible.

- ^ John 5:16. See also the Textus Receptus, Geneva Bible and King James Version. However, Westcott and Hort's critical text (John 5:16) does not include these words.

- ^ Watkins, H. W. (1905), Ellicott's Commentary for English Readers on John 5, accessed 5 March 2016

- ^ Wesley's Notes on John 5, accessed 5 March 2016

- ^ Schaff, P. (ed.), Homilies or Tractates of St. Augustin on the Gospel of John, Tractate XVIII, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers in the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- ^ Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary on John 5, accessed 6 March 2016

- ^ D. A. Carson, The Gospel According to John (Apollos, 1991), p. 256.

- ^ Meyer's NT Commentary on John 5, accessed 8 March 2016

- ^ Barnes' Notes on the Bible on Deuteronomy 18, accessed 10 March 2016

External links

[edit]- John 5 King James Bible – Wikisource

- English Translation with Parallel Latin Vulgate

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Multiple bible versions at Bible Gateway (NKJV, NIV, NRSV etc.)

| Preceded by John 4 |

Chapters of the Bible Gospel of John |

Succeeded by John 6 |