Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Annas

View on Wikipedia

Annas (also Ananus[1] or Ananias;[2] Hebrew: חָנָן, Ḥānān; Koine Greek: Ἅννας, Hánnas; 23/22 BC – death date unknown,[3] probably around AD 40) was appointed by the Roman legate Quirinius as the first High Priest of the newly formed Roman province of Judaea in AD 6 – just after the Romans had deposed Archelaus, Ethnarch of Judaea, thereby putting Judaea directly under Roman rule.

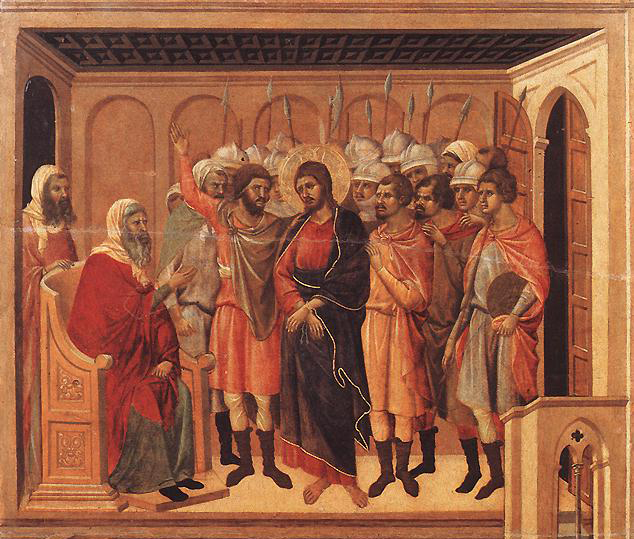

Annas appears in the Gospels and Passion plays as a high priest before whom Jesus is brought for judgment, prior to being brought before Pontius Pilate.

The sacerdotal family

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

The terms of Annas, Caiaphas, and the five brothers are:

Ananus (or Annas), son of Seth (6–15)

[edit]Annas served officially as High Priest for ten years (AD 6–15), when at the age of 36 he was deposed by the procurator Valerius Gratus. Yet while having been officially removed from office, he remained as one of the nation's most influential political and social individuals, aided greatly by the fact that his five sons and his son-in-law Caiaphas all served at sometime as High Priests.[4] His death is unrecorded. His son Annas the Younger, also known as Ananus the son of Ananus, was assassinated in AD 66 for advocating peace with Rome.[2]

Eleazar ben Ananus (16–17)

[edit]After Valerius Gratus deposed Ishmael ben Fabus from the high priesthood, he installed Eleazar ben Ananus, (15—16),[5][6] a descendant of John Hyrcanus. It was a time of turbulence in Jewish politics, with the role of the high priesthood being contended for by several priestly families. Eleazar was likewise deposed by Gratus, who gave the office to Simon ben Camithus (17-18).

Caiaphas was married to the daughter of Annas (John 18:13). Gratus made him high priest after depriving Simon ben Camithus of the office.[5] The comparatively long eighteen-year tenure of Caiaphas suggests he had established a good working relationship with the Roman authorities. Gratus' successor Pontius Pilate retained him as high priest.[7]

Jonathan ben Ananus (36–37)

[edit]This section needs expansion with: comparable text description and source to support the contentions of the section heading and the table following. You can help by adding missing information. (March 2024) |

Theophilus ben Ananus (37–41)

[edit]This section needs expansion with: comparable text description and source to support the contentions of the section heading and the table following. You can help by adding missing information. (March 2024) |

Matthias ben Ananus (43)

[edit]This section needs expansion with: comparable text description and source to support the contentions of the section heading and the table following. You can help by adding missing information. (March 2024) |

Jonathan ben Ananus (44)

[edit]This section needs expansion with: comparable text description and source to support the contentions of the section heading and the table following. You can help by adding missing information. (March 2024) |

Ananus ben Ananus (63)

[edit]This section needs expansion with: sources to support text that appears, as well as the contentions of the section heading and the table following. You can help by adding missing information. (March 2024) |

References in the Mosaic Law to "the death of the high priest" (Numbers 35:25, 28) suggest that the high-priesthood was ordinarily held for life.[citation needed] Annas was still called "high priest" even after his dismissal, along with Caiaphas (Luke 3:2),[non-primary source needed] perhaps for that reason.[verification needed][citation needed] It is also thought[according to whom?] that Annas also may have been acting as president of the Sanhedrin, or a coadjutor of the high priest.[verification needed][citation needed]

In the New Testament

[edit]This section may contain original research. (March 2024) |

The trial of Jesus

[edit]Although Caiaphas was the properly appointed high priest, Annas, being his father-in-law and a former incumbent of the office, possibly retained some of the power attached to the position.[8] According to the Gospel of John (the event is not mentioned in other accounts), Jesus was first brought before Annas, whose palace was closer.[9] Annas questioned him regarding his disciples and teaching, and then sent him on to Caiaphas, where some members of the Sanhedrin had met, and where in Matthew's account the first trial of Jesus took place (Matthew 26:57–68).

In the Book of Acts

[edit]After Pentecost, Annas presided over the Sanhedrin before which the Apostles Peter and John were brought (Acts 4:6).

Cultural references

[edit]Annas has an important role in Jesus Christ Superstar, as one of the two main antagonists of the show (the other being Caiaphas) spurring Pontius Pilate to take action against Jesus. In almost all versions, Annas has a high voice to contrast against Caiaphas' bass. Despite being Caiaphas' father-in-law, Annas is generally played by a younger actor.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Josephus, The Complete Works, Thomas Nelson Publishers (Nashville, Tennessee, US), 20.9.1 (1998)

- ^ a b Goodman, Martin, "Rome & Jerusalem", Penguin Books, p.12 (2007)

- ^ "Glossary | Ananus Ben Seth".

- ^ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities XX, 9.1; "It is said that the elder Ananus was extremely fortunate. For he had five sons, all of whom, after he himself had previously enjoyed the office for a very long period, became high priests of God - a thing that had never happened to any other of our high priests."

- ^ a b Josephus Antiquities 18.2.2

- ^ "High Priests of the Second Temple Period", Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Lendering, Jona. "Caiaphas". www.livius.org.

- ^ Enelow, H.G., "Annas", Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Gottheil, Richard; Krauss, Samuel. "Caiaphas". 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Annas". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Annas". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

External links

[edit]Annas

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Appointment

Origins and Family Background

Annas, whose Hebrew name was Ananus ben Seth, was born into the Jewish priestly aristocracy of Judea during the late Second Temple era, with his father Seth belonging to the Sadducean elite that controlled Temple administration.[5] Limited historical records exist on his early life or precise birth date, estimated around 20–30 BC based on his appointment to the high priesthood at a typical adult age for such offices, but primary sources like Josephus provide no further ancestral details beyond this patrilineal identification, suggesting a background rooted in established Zadokite or comparable priestly lineages favored by Roman procurators for their pliability in governance.[6] The defining feature of Annas' family background was its dynastic dominance over the high priesthood, which Josephus attributes to strategic marriages and Roman patronage rather than hereditary legitimacy under Hasmonean precedents.[7] He fathered at least five sons—Eleazar, Jonathan, Theophilus, Matthias, and a second Ananus (the younger)—each of whom successively held the high priesthood after his own tenure, spanning from approximately AD 16 to 62 and enabling the family to retain de facto authority over Temple revenues and rituals for over half a century.[7] Josephus notes this as evidence of Annas' "fortune," with his daughters marrying into other influential families, including one to Joseph Caiaphas, who served as high priest from AD 18 to 36 and acted as Annas' close political ally.[7] This network exemplified the shift from hereditary to appointive high priesthood under Roman rule, where familial alliances secured repeated Roman endorsements despite frequent depositions.[6]Appointment as High Priest (6 AD)

Annas ben Seth was appointed High Priest of Judea in 6 CE by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, the Roman legate of Syria, amid the transition to direct Roman provincial administration following the deposition of ethnarch Herod Archelaus by Emperor Augustus.[8] Quirinius, dispatched to conduct a census and suppress unrest, exercised authority to install Annas, replacing Joazar ben Boethus, as part of efforts to stabilize governance and integrate Judea into the imperial tax system.[9] This appointment, detailed in Flavius Josephus's Antiquities of the Jews (18.2.1–2), reflected Roman preference for Sadducean elites amenable to collaboration, with Annas hailing from a priestly lineage that positioned him to navigate both Temple rituals and prefectural demands.[10] The selection occurred against a backdrop of Jewish resistance to the census, viewed as a harbinger of heavier taxation and loss of autonomy, which sparked revolts led by Judas of Galilee.[11] Annas's tenure thus began under strained conditions, requiring him to mediate between Roman imperatives—such as ensuring orderly revenue collection—and Jewish expectations of priestly legitimacy derived from Zadokite descent, though Roman veto power increasingly superseded hereditary claims.[3] His role emphasized the high priesthood's evolution into a politically appointed office, prioritizing administrative utility over purely religious criteria.Initial Tenure and Roman Relations (6-15 AD)

Annas ben Seth was appointed high priest in 6 AD by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, the Roman legate of Syria, shortly after the annexation of Judaea as a Roman province following the deposition of Herod Archelaus.[12][3] This selection replaced Joazar ben Boethus and aligned with Quirinius's administrative reforms, including the controversial census that assessed property for taxation and triggered the Galilean revolt led by Judas of Galilee and Zadok the Pharisee.[12] As the first high priest under direct Roman provincial governance, Annas's installation underscored the empire's strategy of appointing cooperative Sadducean elites to manage temple affairs and mitigate unrest, thereby ensuring fiscal contributions to Rome flowed through Jerusalem's religious institutions.[3] Throughout his tenure, Annas maintained functional relations with Roman authorities by upholding the status quo of priestly Sadducean dominance, which prioritized temple revenues—estimated from sacrifices, tithes, and trade—over zealous resistance to imperial demands.[3] No major revolts directly implicated him, suggesting effective mediation between Roman prefects and Jewish factions during a period of adjustment to provincial rule, though underlying tensions from the 6 AD census persisted.[12] His approximately nine-year hold on the office, longer than many contemporaries, reflected pragmatic alignment with Roman interests, as high priests derived legitimacy and security from imperial favor rather than solely from Hasmonean or popular mandate.[3] In 15 AD, Valerius Gratus, the newly appointed Roman prefect of Judaea, deposed Annas and replaced him with Ishmael ben Phiabi, initiating a pattern of rapid high priestly turnovers to consolidate procuratorial control.[12][3] The deposition, executed without recorded cause in primary accounts, likely stemmed from Gratus's efforts to install more pliable figures amid ongoing fiscal pressures, though Annas's family retained informal influence over subsequent appointees.[3] This event highlighted the precariousness of Jewish leadership under Roman oversight, where tenure depended on perceived loyalty and utility to imperial administration.[12]Dynastic Influence and Family Priesthood

Key Family Members and Their Tenures

Annas exerted dynastic control over the high priesthood through his immediate family, with five sons and one son-in-law appointed to the office by Roman authorities in the decades following his own tenure.[3] These included Eleazar, Jonathan, Theophilus, Matthias, Ananus the younger, and Joseph Caiaphas, married to Annas' daughter.[3] This succession, spanning from 16 CE to 62 CE, reflected the family's entrenched influence amid frequent Roman interventions in priestly appointments, as detailed by Josephus.[5][7] The specific tenures of these key family members were:| Name | Relation to Annas | Tenure as High Priest |

|---|---|---|

| Eleazar ben Ananus | Son | 16–17 CE |

| Joseph Caiaphas | Son-in-law | 18–36 CE |

| Jonathan ben Ananus | Son | 36–37 CE |

| Theophilus ben Ananus | Son | 37–41 CE |

| Matthias ben Ananus | Son | 43 CE |

| Ananus ben Ananus | Son | 62 CE |