Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

LDL receptor

View on Wikipedia

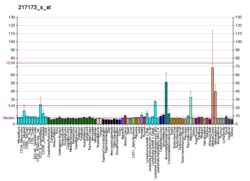

The low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) is a mosaic protein of 839 amino acids (after removal of 21-amino acid signal peptide)[5] that mediates the endocytosis of cholesterol-rich low-density lipoprotein (LDL). It is a cell-surface receptor that recognizes apolipoprotein B100 (ApoB100), which is embedded in the outer phospholipid layer of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), their remnants—i.e. intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), and LDL particles. The receptor also recognizes apolipoprotein E (ApoE) which is found in chylomicron remnants and IDL. In humans, the LDL receptor protein is encoded by the LDLR gene on chromosome 19.[6][7][8] It belongs to the low density lipoprotein receptor gene family.[9] It is most significantly expressed in bronchial epithelial cells and adrenal gland and cortex tissue.[10]

Michael S. Brown and Joseph L. Goldstein were awarded the 1985 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their identification of LDL-R[11] and its relation to cholesterol metabolism and familial hypercholesterolemia.[12] Disruption of LDL-R can lead to higher LDL-cholesterol as well as increasing the risk of related diseases. Individuals with disruptive mutations (defined as nonsense, splice site, or indel frameshift) in LDLR have an average LDL-cholesterol of 279 mg/dL, compared with 135 mg/dL for individuals with neither disruptive nor deleterious mutations. Disruptive mutations were 13 times more common in individuals with early-onset myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease than in individuals without either disease.[13]

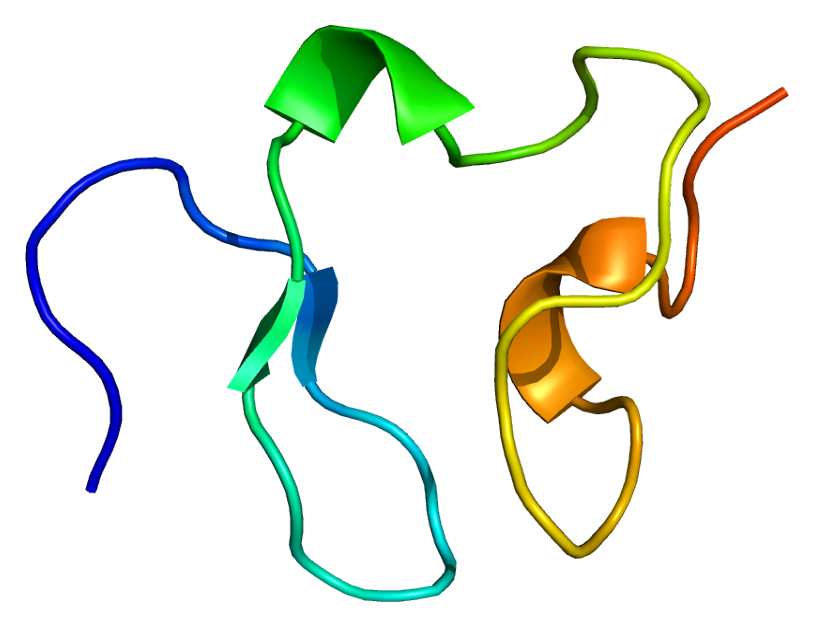

Structure

[edit]Gene

[edit]The LDLR gene resides on chromosome 19 at the band 19p13.2 and is split into 18 exons.[8] Exon 1 contains a signal sequence that localises the receptor to the endoplasmic reticulum for transport to the cell surface. Beyond this, exons 2-6 code the ligand binding region; 7-14 code the epidermal growth factor (EGF) domain; 15 codes the oligosaccharide rich region; 16 (and some of 17) code the membrane spanning region; and 18 (with the rest of 17) code the cytosolic domain.

This gene produces 6 isoforms through alternative splicing.[14]

Protein

[edit]This protein belongs to the LDLR family and is made up of a number of functionally distinct domains, including 3 EGF-like domains, 7 LDL-R class A domains, and 6 LDL-R class B repeats.[14]

The N-terminal domain of the LDL receptor, which is responsible for ligand binding, is composed of seven sequence repeats (~50% identical). Each repeat, referred to as a class A repeat or LDL-A, contains roughly 40 amino acids, including 6 cysteine residues that form disulfide bonds within the repeat. Additionally, each repeat has highly conserved acidic residues which it uses to coordinate a single calcium ion in an octahedral lattice. Both the disulfide bonds and calcium coordination are necessary for the structural integrity of the domain during the receptor's repeated trips to the highly acidic interior of the endosome. The exact mechanism of interaction between the class A repeats and ligand (LDL) is unknown, but it is thought that the repeats act as "grabbers" to hold the LDL. Binding of ApoB requires repeats 2-7 while binding ApoE requires only repeat 5 (thought to be the ancestral repeat).

Next to the ligand binding domain is an EGF precursor homology domain (EGFP domain). This shows approximately 30% homology with the EGF precursor gene. There are three "growth factor" repeats; A, B and C. A and B are closely linked while C is separated by the YWTD repeat region, which adopts a beta-propeller conformation (LDL-R class B domain). It is thought that this region is responsible for the pH-dependent conformational shift that causes bound LDL to be released in the endosome.

A third domain of the protein is rich in O-linked oligosaccharides but appears to show little function. Knockout experiments have confirmed that no significant loss of activity occurs without this domain. It has been speculated that the domain may have ancestrally acted as a spacer to push the receptor beyond the extracellular matrix.

The single transmembrane domain of 22 (mostly) non-polar residues crosses the plasma membrane in a single alpha helix.

The cytosolic C-terminal domain contains ~50 amino acids, including a signal sequence important for localizing the receptors to clathrin-coated pits and for triggering receptor-mediated endocytosis after binding. Portions of the cytosolic sequence have been found in other lipoprotein receptors, as well as in more distant receptor relatives.[15][16][17]

Mutations

[edit]Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the LDL receptor are known to cause familial hypercholesterolaemia.

There are 5 broad classes of mutation of the LDL receptor:

- Class 1 mutations affect the synthesis of the receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

- Class 2 mutations prevent proper transport to the Golgi body needed for modifications to the receptor.

- e.g. a truncation of the receptor protein at residue number 660 leads to domains 3,4 and 5 of the EGF precursor domain being missing. This precludes the movement of the receptor from the ER to the Golgi, and leads to degradation of the receptor protein.

- Class 3 mutations stop the binding of LDL to the receptor.

- e.g. repeat 6 of the ligand binding domain (N-terminal, extracellular fluid) is deleted.

- Class 4 mutations inhibit the internalization of the receptor-ligand complex.

- e.g. "JD" mutant results from a single point mutation in the NPVY domain (C-terminal, cytosolic; C residue converted to a Y, residue number 807). This domain recruits clathrin and other proteins responsible for the endocytosis of LDL, therefore this mutation inhibits LDL internalization.

- Class 5 mutations give rise to receptors that cannot recycle properly. This leads to a relatively mild phenotype as receptors are still present on the cell surface (but all must be newly synthesised).[18]

Gain-of-function mutations decrease LDL levels and are a target of research to develop a gene therapy to treat refractory hypercholesterolemia.[19]

Function

[edit]LDL receptor mediates the endocytosis of cholesterol-rich LDL and thus maintains the plasma level of LDL.[20] This occurs in all nucleated cells, but mainly in the liver which removes ~70% of LDL from the circulation. LDL receptors are clustered in clathrin-coated pits, and coated pits pinch off from the surface to form coated endocytic vesicles that carry LDL into the cell.[21] After internalization, the receptors dissociate from their ligands when they are exposed to lower pH in endosomes. After dissociation, the receptor folds back on itself to obtain a closed conformation and recycles to the cell surface.[22] The rapid recycling of LDL receptors provides an efficient mechanism for delivery of cholesterol to cells.[23][24] It was also reported that by association with lipoprotein in the blood, viruses such as hepatitis C virus, Flaviviridae viruses and bovine viral diarrheal virus could enter cells indirectly via LDLR-mediated endocytosis.[25] LDLR has been identified as the primary mode of entry for the Vesicular stomatitis virus in mice and humans.[26] In addition, LDLR modulation is associated with early atherosclerosis-related lymphatic dysfunction.[27] Synthesis of receptors in the cell is regulated by the level of free intracellular cholesterol; if it is in excess for the needs of the cell then the transcription of the receptor gene will be inhibited.[28] LDL receptors are translated by ribosomes on the endoplasmic reticulum and are modified by the Golgi apparatus before travelling in vesicles to the cell surface.

Clinical significance

[edit]In humans, LDL is directly involved in the development of atherosclerosis, which is the process responsible for the majority of cardiovascular diseases, due to accumulation of LDL-cholesterol in the blood [citation needed]. Hyperthyroidism may be associated with reduced cholesterol via upregulation of the LDL receptor, and hypothyroidism with the converse. A vast number of studies have described the relevance of LDL receptors in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, and steatohepatitis.[29][30] Previously, rare mutations in LDL-genes have been shown to contribute to myocardial infarction risk in individual families, whereas common variants at more than 45 loci have been associated with myocardial infarction risk in the population. When compared with non-carriers, LDLR mutation carriers had higher plasma LDL cholesterol, whereas APOA5 mutation carriers had higher plasma triglycerides.[31] Recent evidence has connected MI risk with coding-sequence mutations at two genes functionally related to APOA5, namely lipoprotein lipase and apolipoprotein C-III.[32][33] Combined, these observations suggest that, as well as LDL cholesterol, disordered metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins contributes to MI risk. Overall, LDLR has a high clinical relevance in blood lipids.[34][35]

Clinical marker

[edit]A multi-locus genetic risk score study based on a combination of 27 loci, including the LDLR gene, identified individuals at increased risk for both incident and recurrent coronary artery disease events, as well as an enhanced clinical benefit from statin therapy. The study was based on a community cohort study (the Malmö Diet and Cancer study) and four additional randomized controlled trials of primary prevention cohorts (JUPITER and ASCOT) and secondary prevention cohorts (CARE and PROVE IT-TIMI 22).[36]

Interactive pathway map

[edit]Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.[§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000130164 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000032193 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Südhof TC, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Russell DW (May 1985). "The LDL receptor gene: a mosaic of exons shared with different proteins". Science. 228 (4701): 815–22. Bibcode:1985Sci...228..815S. doi:10.1126/science.2988123. PMC 4450672. PMID 2988123.

- ^ Francke U, Brown MS, Goldstein JL (May 1984). "Assignment of the human gene for the low density lipoprotein receptor to chromosome 19: synteny of a receptor, a ligand, and a genetic disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (9): 2826–30. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.2826F. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.9.2826. PMC 345163. PMID 6326146.

- ^ Lindgren V, Luskey KL, Russell DW, Francke U (December 1985). "Human genes involved in cholesterol metabolism: chromosomal mapping of the loci for the low density lipoprotein receptor and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase with cDNA probes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 82 (24): 8567–71. Bibcode:1985PNAS...82.8567L. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.24.8567. PMC 390958. PMID 3866240.

- ^ a b "LDLR low density lipoprotein receptor [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ Nykjaer A, Willnow TE (June 2002). "The low-density lipoprotein receptor gene family: a cellular Swiss army knife?". Trends in Cell Biology. 12 (6): 273–80. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02282-1. PMID 12074887.

- ^ "BioGPS - your Gene Portal System". biogps.org. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1985" (Press release). The Royal Swedish Academy of Science. 1985. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ Brown MS, Goldstein JL (November 1984). "How LDL receptors influence cholesterol and atherosclerosis". Scientific American. 251 (5): 58–66. Bibcode:1984SciAm.251c..52K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0984-52. PMID 6390676.

- ^ Do R, Stitziel NO, Won HH, Jørgensen AB, Duga S, Angelica Merlini P, et al. (February 2015). "Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction". Nature. 518 (7537): 102–6. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..102.. doi:10.1038/nature13917. PMC 4319990. PMID 25487149.

- ^ a b "LDLR - Low-density lipoprotein receptor precursor - Homo sapiens (Human) - LDLR gene & protein". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ Yamamoto T, Davis CG, Brown MS, Schneider WJ, Casey ML, Goldstein JL, et al. (November 1984). "The human LDL receptor: a cysteine-rich protein with multiple Alu sequences in its mRNA". Cell. 39 (1): 27–38. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90188-0. PMID 6091915. S2CID 25822170.

- ^ Brown MS, Herz J, Goldstein JL (August 1997). "LDL-receptor structure. Calcium cages, acid baths and recycling receptors". Nature. 388 (6643): 629–30. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..629B. doi:10.1038/41672. PMID 9262394. S2CID 33590160.

- ^ Gent J, Braakman I (October 2004). "Low-density lipoprotein receptor structure and folding". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 61 (19–20): 2461–70. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4090-3. PMC 11924501. PMID 15526154. S2CID 21235282.

- ^ "Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor". LOVD v.1.1.0 - Leiden Open Variation Database. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ^ Srivastava RA (December 2023). "New opportunities in the management and treatment of refractory hypercholesterolemia using in vivo CRISPR-mediated genome/base editing". Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 33 (12): 2317–2325. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2023.08.010. PMID 37805309.

- ^ Leren TP (November 2014). "Sorting an LDL receptor with bound PCSK9 to intracellular degradation". Atherosclerosis. 237 (1): 76–81. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.038. PMID 25222343.

- ^ Goldstein JL, Brown MS (April 2009). "The LDL receptor". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 29 (4): 431–8. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179564. PMC 2740366. PMID 19299327.

- ^ Rudenko G, Henry L, Henderson K, Ichtchenko K, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, et al. (December 2002). "Structure of the LDL receptor extracellular domain at endosomal pH". Science. 298 (5602): 2353–8. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.2353R. doi:10.1126/science.1078124. PMID 12459547. S2CID 17712211.

- ^ Basu SK, Goldstein JL, Anderson RG, Brown MS (May 1981). "Monensin interrupts the recycling of low density lipoprotein receptors in human fibroblasts". Cell. 24 (2): 493–502. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(81)90340-8. PMID 6263497. S2CID 29553611.

- ^ Brown MS, Anderson RG, Goldstein JL (March 1983). "Recycling receptors: the round-trip itinerary of migrant membrane proteins". Cell. 32 (3): 663–7. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90052-1. PMID 6299572. S2CID 34919831.

- ^ Agnello V, Abel G, Elfahal M, Knight GB, Zhang QX (October 1999). "Hepatitis C virus and other flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (22): 12766–71. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612766A. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.22.12766. PMC 23090. PMID 10535997.

- ^ Finkelshtein D, Werman A, Novick D, Barak S, Rubinstein M (April 2013). "LDL receptor and its family members serve as the cellular receptors for vesicular stomatitis virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (18): 7306–11. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.7306F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1214441110. PMC 3645523. PMID 23589850.

- ^ Milasan A, Dallaire F, Mayer G, Martel C (2016-01-01). "Effects of LDL Receptor Modulation on Lymphatic Function". Scientific Reports. 6 27862. Bibcode:2016NatSR...627862M. doi:10.1038/srep27862. PMC 4899717. PMID 27279328.

- ^ Smith JR, Osborne TF, Goldstein JL, Brown MS (Feb 1990). "Identification of nucleotides responsible for enhancer activity of sterol regulatory element in low density lipoprotein receptor gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (4): 2306–10. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)39976-4. PMID 2298751. S2CID 26062629.

- ^ Hsieh J, Koseki M, Molusky MM, Yakushiji E, Ichi I, Westerterp M, et al. (July 2016). "TTC39B deficiency stabilizes LXR reducing both atherosclerosis and steatohepatitis". Nature. 535 (7611): 303–7. Bibcode:2016Natur.535..303H. doi:10.1038/nature18628. PMC 4947007. PMID 27383786.

- ^ Walter K, Min JL, Huang J, Crooks L, Memari Y, McCarthy S, et al. (October 2015). "The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease". Nature. 526 (7571): 82–90. Bibcode:2015Natur.526...82T. doi:10.1038/nature14962. PMC 4773891. PMID 26367797.

- ^ Rose-Hellekant TA, Schroeder MD, Brockman JL, Zhdankin O, Bolstad R, Chen KS, et al. (August 2007). "Estrogen receptor-positive mammary tumorigenesis in TGFalpha transgenic mice progresses with progesterone receptor loss". Oncogene. 26 (36): 5238–46. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210340. PMC 2587149. PMID 17334393.

- ^ Crosby J, Peloso GM, Auer PL, Crosslin DR, Stitziel NO, Lange LA, et al. (July 2014). "Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1307095. PMC 4180269. PMID 24941081.

- ^ Jørgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A (July 2014). "Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308027. PMID 24941082. S2CID 26995834.

- ^ Shuldiner AR, Pollin TI (August 2010). "Genomics: Variations in blood lipids". Nature. 466 (7307): 703–4. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..703S. doi:10.1038/466703a. PMID 20686562. S2CID 205057802.

- ^ Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, et al. (August 2010). "Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids". Nature. 466 (7307): 707–13. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..707T. doi:10.1038/nature09270. PMC 3039276. PMID 20686565.

- ^ Mega JL, Stitziel NO, Smith JG, Chasman DI, Caulfield MJ, Devlin JJ, et al. (June 2015). "Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials". Lancet. 385 (9984): 2264–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61730-X. PMC 4608367. PMID 25748612.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown MS, Goldstein JL (July 1979). "Receptor-mediated endocytosis: insights from the lipoprotein receptor system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (7): 3330–7. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.3330B. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.7.3330. PMC 383819. PMID 226968.

- Hobbs HH, Brown MS, Goldstein JL (1993). "Molecular genetics of the LDL receptor gene in familial hypercholesterolemia". Human Mutation. 1 (6): 445–66. doi:10.1002/humu.1380010602. PMID 1301956. S2CID 5756814.

- Fogelman AM, Van Lenten BJ, Warden C, Haberland ME, Edwards PA (1989). "Macrophage lipoprotein receptors". Journal of Cell Science. Supplement. 9: 135–49. doi:10.1242/jcs.1988.supplement_9.7. PMID 2855802.

- Barrett PH, Watts GF (March 2002). "Shifting the LDL-receptor paradigm in familial hypercholesterolemia: novel insights from recent kinetic studies of apolipoprotein B-100 metabolism". Atherosclerosis. Supplements. 2 (3): 1–4. doi:10.1016/S1567-5688(01)00012-5. PMID 11923121.

- May P, Bock HH, Herz J (April 2003). "Integration of endocytosis and signal transduction by lipoprotein receptors". Science's STKE. 2003 (176) PE12. doi:10.1126/stke.2003.176.pe12. PMID 12671190. S2CID 24468290.

- Gent J, Braakman I (October 2004). "Low-density lipoprotein receptor structure and folding". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 61 (19–20): 2461–70. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4090-3. PMC 11924501. PMID 15526154. S2CID 21235282.

External links

[edit]- Description of LDL receptor pathway at the Brown - Goldstein Laboratory webpage

- LDL+Receptor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)