Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reelin

View on Wikipedia

Reelin, encoded by the RELN gene,[5] is a large secreted extracellular matrix glycoprotein that helps regulate processes of neuronal migration and positioning in the developing brain by controlling cell–cell interactions. Besides this important role in early development, reelin continues to work in the adult brain.[6] It modulates synaptic plasticity by enhancing the induction and maintenance of long-term potentiation.[7][8] It also stimulates dendrite and dendritic spine development in the hippocampus,[9][10] and regulates the continuing migration of neuroblasts generated in adult neurogenesis sites of the subventricular and subgranular zones. It is found not only in the brain but also in the liver, thyroid gland, adrenal gland, fallopian tube, breast and in comparatively lower levels across a range of anatomical regions.[11]

Reelin has been suggested to be implicated in pathogenesis of several brain diseases. The expression of the protein has been found to be significantly lower in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder,[12] but the cause of this observation remains uncertain, as studies show that psychotropic medication itself affects reelin expression. Moreover, epigenetic hypotheses aimed at explaining the changed levels of reelin expression[13] are controversial.[14][15] Total lack of reelin causes a form of lissencephaly. Reelin may also play a role in Alzheimer's disease,[16] temporal lobe epilepsy and autism.

Reelin's name comes from the abnormal reeling gait of reeler mice,[17] which were later found to have a deficiency of this brain protein and were homozygous for mutation of the RELN gene. The primary phenotype associated with loss of reelin function is a failure of neuronal positioning throughout the developing central nervous system (CNS). The mice heterozygous for the reelin gene, while having little neuroanatomical defects, display the endophenotypic traits linked to psychotic disorders.[18]

Discovery

[edit]

Mutant mice have provided insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of the development of the central nervous system. Useful spontaneous mutations were first identified by scientists who were interested in motor behavior, and it proved relatively easy to screen littermates for mice that showed difficulties moving around the cage. A number of such mice were found and given descriptive names such as reeler, weaver, lurcher, nervous, and staggerer.[citation needed]

The "reeler" mouse was described for the first time in 1951 by D.S.Falconer in Edinburgh University as a spontaneous variant arising in a colony of at least mildly inbred snowy-white bellied mice stock in 1948.[17] Histopathological studies in the 1960s revealed that the cerebellum of reeler mice is dramatically decreased in size while the normal laminar organization found in several brain regions is disrupted.[19] The 1970s brought about the discovery of cellular layer inversion in the mouse neocortex,[20] which attracted more attention to the reeler mutation.

In 1994, a new allele of reeler was obtained by means of insertional mutagenesis.[21] This provided the first molecular marker of the locus, permitting the RELN gene to be mapped to chromosome 7q22 and subsequently cloned and identified.[22] Japanese scientists at Kochi Medical School successfully raised antibodies against normal brain extracts in reeler mice, later these antibodies were found to be specific monoclonal antibodies for reelin, and were termed CR-50 (Cajal-Retzius marker 50).[23] They noted that CR-50 reacted specifically with Cajal-Retzius neurons, whose functional role was unknown until then.[citation needed]

The Reelin receptors, apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR), were discovered by Trommsdorff, Herz and colleagues, who initially found that the cytosolic adaptor protein Dab1 interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of LDL receptor family members.[24] They then went on to show that the double knockout mice for ApoER2 and VLDLR, which both interact with Dab1, had cortical layering defects similar to those in reeler.[25]

The downstream pathway of reelin was further clarified with the help of other mutant mice, including yotari and scrambler. These mutants have phenotypes similar to that of reeler mice, but without mutation in reelin. It was then demonstrated that the mouse disabled homologue 1 (Dab1) gene is responsible for the phenotypes of these mutant mice, as Dab1 protein was absent (yotari) or only barely detectable (scrambler) in these mutants.[26] Targeted disruption of Dab1 also caused a phenotype similar to that of reeler. Pinpointing the DAB1 as a pivotal regulator of the reelin signaling cascade started the tedious process of deciphering its complex interactions.[citation needed]

There followed a series of speculative reports linking reelin's genetic variation and interactions to schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, autism and other highly complex dysfunctions. These and other discoveries, coupled with the perspective of unraveling the evolutionary changes that allowed for the creation of human brain, highly intensified the research. As of 2008, some 13 years after the gene coding the protein was discovered, hundreds of scientific articles address the multiple aspects of its structure and functioning.[27][28]

Tissue distribution and secretion

[edit]Studies show that reelin is absent from synaptic vesicles and is secreted via constitutive secretory pathway, being stored in Golgi secretory vesicles.[29] Reelin's release rate is not regulated by depolarization, but strictly depends on its synthesis rate. This relationship is similar to that reported for the secretion of other extracellular matrix proteins.[citation needed]

During the brain development, reelin is secreted in the cortex and hippocampus by the so-called Cajal-Retzius cells, Cajal cells, and Retzius cells.[30] Reelin-expressing cells in the prenatal and early postnatal brain are predominantly found in the marginal zone (MZ) of the cortex and in the temporary subpial granular layer (SGL), which is manifested to the highest extent in human,[31] and in the hippocampal stratum lacunosum-moleculare and the upper marginal layer of the dentate gyrus.

In the developing cerebellum, reelin is expressed first in the external granule cell layer (EGL), before the granule cell migration to the internal granule cell layer (IGL) takes place.[32]

Having peaked just after the birth, the synthesis of reelin subsequently goes down sharply, becoming more diffuse compared with the distinctly laminar expression in the developing brain. In the adult brain, reelin is expressed by GABA-ergic interneurons of the cortex and glutamatergic cerebellar neurons,[33] the glutamatergic stellate cells and fan cells in the superficial entorhinal cortex that are supposed to carry a role in encoding new episodic memories,[34] and by the few extant Cajal-Retzius cells. Among GABAergic interneurons, reelin seems to be detected predominantly in those expressing calretinin and calbindin, like bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells, but not parvalbumin-expressing cells, like chandelier or basket neurons.[35][36] In the white matter, a minute proportion of interstitial neurons has also been found to stain positive for reelin expression.[37]

Outside the brain, reelin is found in adult mammalian blood, liver, pituitary pars intermedia, and adrenal chromaffin cells.[38] In the liver, reelin is localized in hepatic stellate cells.[39] The expression of reelin increases when the liver is damaged, and returns to normal following its repair.[40] In the eyes, reelin is secreted by retinal ganglion cells and is also found in the endothelial layer of the cornea.[41] Just as in the liver, its expression increases after an injury has taken place.[citation needed]

The protein is also produced by the odontoblasts, which are cells at the margins of the dental pulp. Reelin is found here both during odontogenesis and in the mature tooth.[42] Some authors suggest that odontoblasts play an additional role as sensory cells able to transduce pain signals to the nerve endings.[43] According to the hypothesis, reelin participates in the process[28] by enhancing the contact between odontoblasts and the nerve terminals.[44]

Structure

[edit]

Reelin is composed of 3461 amino acids with a relative molecular mass of 388 kDa. It also has serine protease activity.[46] Murine RELN gene consists of 65 exons spanning approximately 450 kb.[47] One exon, coding for only two amino acids near the protein's C-terminus, undergoes alternative splicing, but the exact functional impact of this is unknown.[28] Two transcription initiation sites and two polyadenylation sites are identified in the gene structure.[47]

The reelin protein starts with a signaling peptide 27 amino acids in length, followed by a region bearing similarity to F-spondin (the reeler domain), marked as "SP" on the scheme, and by a region unique to reelin, marked as "H". Next comes 8 repeats of 300–350 amino acids. These are called reelin repeats and have an epidermal growth factor motif at their center, dividing each repeat into two subrepeats, A (the BNR/Asp-box repeat) and B (the EGF-like domain). Despite this interruption, the two subdomains make direct contact, resulting in a compact overall structure.[48]

The final reelin domain contains a highly basic and short C-terminal region (CTR, marked "+") with a length of 32 amino acids. This region is highly conserved, being 100% identical in all investigated mammals. It was thought that CTR is necessary for reelin secretion, because the Orleans reeler mutation, which lacks a part of 8th repeat and the whole CTR, is unable to secrete the misshaped protein, leading to its concentration in cytoplasm. However, other studies have shown that the CTR is not essential for secretion itself, but mutants lacking the CTR were much less efficient in activating downstream signaling events.[49]

Reelin is cleaved in vivo at two sites located after domains 2 and 6 – approximately between repeats 2 and 3 and between repeats 6 and 7, resulting in the production of three fragments.[50] This splitting does not decrease the protein's activity, as constructs made of the predicted central fragments (repeats 3–6) bind to lipoprotein receptors, trigger Dab1 phosphorylation and mimic functions of reelin during cortical plate development.[51] Moreover, the processing of reelin by embryonic neurons may be necessary for proper corticogenesis.[52]

Function

[edit]

The primary functions of Reelin are the regulation of corticogenesis and neuronal cell positioning in the prenatal period, but the protein also continues to play a role in adults. Reelin is found in numerous tissues and organs, and one could roughly subdivide its functional roles by the time of expression and by localisation of its action.[11]

During development

[edit]A number of non-nervous tissues and organs express reelin during development, with the expression sharply going down after organs have been formed. The role of the protein here is largely unexplored, because the knockout mice show no major pathology in these organs. Reelin's role in the growing central nervous system has been extensively characterized. It promotes the differentiation of progenitor cells into radial glia and affects the orientation of its fibers, which serve as the guides for the migrating neuroblasts.[55] The position of reelin-secreting cell layer is important, because the fibers orient themselves in the direction of its higher concentration.[56] For example, reelin regulates the development of layer-specific connections in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex.[57][58]

Mammalian corticogenesis is another process where reelin plays a major role. In this process the temporary layer called preplate is split into the marginal zone on the top and subplate below, and the space between them is populated by neuronal layers in the inside-out pattern. Such an arrangement, where the newly created neurons pass through the settled layers and position themselves one step above, is a distinguishing feature of mammalian brain, in contrast to the evolutionary older reptile cortex, in which layers are positioned in an "outside-in" fashion. When reelin is absent, like in the mutant reeler mouse, the order of cortical layering becomes roughly inverted, with younger neurons finding themselves to be unable to pass the settled layers. Subplate neurons fail to stop and invade the upper most layer, creating the so-called superplate in which they mix with Cajal-Retzius cells and some cells normally destined for the second layer.[citation needed]

There is no agreement concerning the role of reelin in the proper positioning of cortical layers. The original hypothesis, that the protein is a stop signal for the migrating cells, is supported by its ability to induce the dissociation,[59] its role in asserting the compact granule cell layer in the hippocampus, and by the fact that migrating neuroblasts evade the reelin-rich areas. But an experiment in which murine corticogenesis went normally despite the malpositioned reelin secreting layer,[60] and lack of evidence that reelin affects the growth cones and leading edges of neurons, caused some additional hypotheses to be proposed. According to one of them, reelin makes the cells more susceptible to some yet undescribed positional signaling cascade.[citation needed]

Reelin may also ensure correct neuronal positioning in the spinal cord: according to one study, location and level of its expression affects the movement of sympathetic preganglionic neurons.[61]

The protein is thought to act on migrating neuronal precursors and thus controls correct cell positioning in the cortex and other brain structures. The proposed role is one of a dissociation signal for neuronal groups, allowing them to separate and go from tangential chain-migration to radial individual migration.[59] Dissociation detaches migrating neurons from the glial cells that are acting as their guides, converting them into individual cells that can strike out alone to find their final position.[citation needed]

Reelin takes part in the developmental change of NMDA receptor configuration, increasing mobility of NR2B-containing receptors and thus decreasing the time they spend at the synapse.[63][dead link][64][65] It has been hypothesized that this may be a part of the mechanism behind the "NR2B-NR2A switch" that is observed in the brain during its postnatal development.[66] Ongoing reelin secretion by GABAergic hippocampal neurons is necessary to keep NR2B-containing NMDA receptors at a low level.[62]

In adults

[edit]In the adult nervous system, reelin plays an eminent role at the two most active neurogenesis sites, the subventricular zone and the dentate gyrus. In some species, the neuroblasts from the subventricular zone migrate in chains in the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to reach the olfactory bulb, where reelin dissociates them into individual cells that are able to migrate further individually. They change their mode of migration from tangential to radial, and begin using the radial glia fibers as their guides. There are studies showing that along the RMS itself the two receptors, ApoER2 and VLDLR, and their intracellular adapter DAB1 function independently of Reelin,[67] most likely by the influence of a newly proposed ligand, thrombospondin-1.[53] In the adult dentate gyrus, reelin provides guidance cues for new neurons that are constantly arriving to the granule cell layer from subgranular zone, keeping the layer compact.[68]

Reelin also plays an important role in the adult brain by modulating cortical pyramidal neuron dendritic spine expression density, the branching of dendrites, and the expression of long-term potentiation[8] as its secretion is continued diffusely by the GABAergic cortical interneurons those origin is traced to the medial ganglionic eminence.

In the adult organism the non-neural expression is much less widespread, but goes up sharply when some organs are injured.[40][41] The exact function of reelin upregulation following an injury is still being researched.[citation needed]

Evolutionary significance

[edit]

Reelin-DAB1 interactions could have played a key role in the structural evolution of the cortex that evolved from a single layer in the common predecessor of the amniotes into multiple-layered cortex of contemporary mammals.[69] Research shows that reelin expression goes up as the cortex becomes more complex, reaching the maximum in the human brain in which the reelin-secreting Cajal-Retzius cells have significantly more complex axonal arbour.[70] Reelin is present in the telencephalon of all the vertebrates studied so far, but the pattern of expression differs widely. For example, zebrafish have no Cajal-Retzius cells at all; instead, the protein is being secreted by other neurons.[71][72] These cells do not form a dedicated layer in amphibians, and radial migration in their brains is very weak.[71]

As the cortex becomes more complex and convoluted, migration along the radial glia fibers becomes more important for the proper lamination. The emergence of a distinct reelin-secreting layer is thought to play an important role in this evolution.[56] There are conflicting data concerning the importance of this layer,[60] and these are explained in the literature either by the existence of an additional signaling positional mechanism that interacts with the reelin cascade,[60] or by the assumption that mice that are used in such experiments have redundant secretion of reelin[73] compared with more localized synthesis in the human brain.[31]

Cajal-Retzius cells, most of which disappear around the time of birth, coexpress reelin with the HAR1 gene that is thought to have undergone the most significant evolutionary change in humans compared with chimpanzee, being the most "evolutionary accelerated" of the genes from the human accelerated regions.[74] There is also evidence of that variants in the DAB1 gene have been included in a recent selective sweep in Chinese populations.[75][76]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

SFK: Src family kinases.

JIP: JNK-interacting protein 1

Receptors

[edit]Reelin's control of cell-cell interactions is thought to be mediated by binding of reelin to the two members of low density lipoprotein receptor gene family: VLDLR and the ApoER2.[78][79][80][81] The two main reelin receptors seem to have slightly different roles: VLDLR conducts the stop signal, while ApoER2 is essential for the migration of late-born neocortical neurons.[82] It also has been shown that the N-terminal region of reelin, a site distinct from the region of reelin shown to associate with VLDLR/ApoER2 binds to the alpha-3-beta-1 integrin receptor.[83] The proposal that the protocadherin CNR1 behaves as a Reelin receptor[84] has been disproven.[51]

As members of lipoprotein receptor superfamily, both VLDLR and ApoER2 have in their structure an internalization domain called NPxY motif. After binding to the receptors reelin is internalized by endocytosis, and the N-terminal fragment of the protein is re-secreted.[85] This fragment may serve postnatally to prevent apical dendrites of cortical layer II/III pyramidal neurons from overgrowth, acting via a pathway independent of canonical reelin receptors.[86]

Reelin receptors are present on both neurons and glial cells. Furthermore, radial glia express the same amount of ApoER2 but being ten times less rich in VLDLR.[55] beta-1 integrin receptors on glial cells play more important role in neuronal layering than the same receptors on the migrating neuroblasts.[87]

Reelin-dependent strengthening of long-term potentiation is caused by ApoER2 interaction with NMDA receptor. This interaction happens when ApoER2 has a region coded by exon 19. ApoER2 gene is alternatively spliced, with the exon 19-containing variant more actively produced during periods of activity.[88] According to one study, the hippocampal reelin expression rapidly goes up when there is need to store a memory, as demethylases open up the RELN gene.[89] The activation of dendrite growth by reelin is apparently conducted through Src family kinases and is dependent upon the expression of Crk family proteins,[90] consistent with the interaction of Crk and CrkL with tyrosine-phosphorylated Dab1.[91] Moreover, a Cre-loxP recombination mouse model that lacks Crk and CrkL in most neurons[92] was reported to have the reeler phenotype, indicating that Crk/CrkL lie between DAB1 and Akt in the reelin signaling chain.

Signaling cascades

[edit]Reelin activates the signaling cascade of Notch-1, inducing the expression of FABP7 and prompting progenitor cells to assume radial glial phenotype.[93] In addition, corticogenesis in vivo is highly dependent upon reelin being processed by embryonic neurons,[52] which are thought to secrete some as yet unidentified metalloproteinases that free the central signal-competent part of the protein. Some other unknown proteolytic mechanisms may also play a role.[94] It is supposed that full-sized reelin sticks to the extracellular matrix fibers on the higher levels, and the central fragments, as they are being freed up by the breaking up of reelin, are able to permeate into the lower levels.[52] It is possible that as neuroblasts reach the higher levels they stop their migration either because of the heightened combined expression of all forms of reelin, or due to the peculiar mode of action of the full-sized reelin molecules and its homodimers.[28]

The intracellular adaptor DAB1 binds to the VLDLR and ApoER2 through an NPxY motif and is involved in transmission of Reelin signals through these lipoprotein receptors. It becomes phosphorylated by Src[95] and Fyn[96] kinases and apparently stimulates the actin cytoskeleton to change its shape, affecting the proportion of integrin receptors on the cell surface, which leads to the change in adhesion. Phosphorylation of DAB1 leads to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, and this explains the heightened levels of DAB1 in the absence of reelin.[97] Such negative feedback is thought to be important for proper cortical lamination.[98] Activated by two antibodies, VLDLR and ApoER2 cause DAB1 phosphorylation but seemingly without the subsequent degradation and without rescuing the reeler phenotype, and this may indicate that a part of the signal is conducted independently of DAB1.[51]

A protein having an important role in lissencephaly and accordingly called LIS1 (PAFAH1B1), was shown to interact with the intracellular segment of VLDLR, thus reacting to the activation of reelin pathway.[77]

Complexes

[edit]Reelin molecules have been shown[99][100] to form a large protein complex, a disulfide-linked homodimer. If the homodimer fails to form, efficient tyrosine phosphorylation of DAB1 in vitro fails. Moreover, the two main receptors of reelin are able to form clusters[101] that most probably play a major role in the signaling, causing the intracellular adaptor DAB1 to dimerize or oligomerize in its turn. Such clustering has been shown in the study to activate the signaling chain even in the absence of Reelin itself.[101] In addition, reelin itself can cut the peptide bonds holding other proteins together, being a serine protease,[46] and this may affect the cellular adhesion and migration processes. Reelin signaling leads to phosphorylation of actin-interacting protein cofilin 1 at ser3; this may stabilize the actin cytoskeleton and anchor the leading processes of migrating neuroblasts, preventing their further growth.[102][103]

Interaction with Cdk5

[edit]Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5), a major regulator of neuronal migration and positioning, is known to phosphorylate DAB1[104][105][106] and other cytosolic targets of reelin signaling, such as Tau,[107] which could be activated also via reelin-induced deactivation of GSK3B,[108] and NUDEL,[109] associated with Lis1, one of the DAB1 targets. LTP induction by reelin in hippocampal slices fails in p35 knockouts.[110] P35 is a key Cdk5 activator, and double p35/Dab1, p35/RELN, p35/ApoER2, p35/VLDLR knockouts display increased neuronal migration deficits,[110][111] indicating a synergistic action of reelin → ApoER2/VLDLR → DAB1 and p35/p39 → Cdk5 pathways in the normal corticogenesis.

Possible pathological role

[edit]Lissencephaly

[edit]Disruptions of the RELN gene are considered to be the cause of the rare form of lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia classed as a microlissencephaly called Norman-Roberts syndrome.[112][113] The mutations disrupt splicing of the RELN mRNA transcript, resulting in low or undetectable amounts of reelin protein. The phenotype in these patients was characterized by hypotonia, ataxia, and developmental delay, with lack of unsupported sitting and profound mental retardation with little or no language development. Seizures and congenital lymphedema are also present. A novel chromosomal translocation causing the syndrome was described in 2007.[114]

Schizophrenia

[edit]Reduced expression of reelin and its mRNA levels in the brains of schizophrenia sufferers had been reported in 1998[115] and 2000,[116] and independently confirmed in postmortem studies of the hippocampus,[12] cerebellum,[117] basal ganglia,[118] and cerebral cortex.[119][120] The reduction may reach up to 50% in some brain regions and is coupled with reduced expression of GAD-67 enzyme,[117] which catalyses the transition of glutamate to GABA. Blood levels of reelin and its isoforms are also altered in schizophrenia, along with mood disorders, according to one study.[121] Reduced reelin mRNA prefrontal expression in schizophrenia was found to be the most statistically relevant disturbance found in the multicenter study conducted in 14 separate laboratories in 2001 by Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortium.[122]

Epigenetic hypermethylation of DNA in schizophrenia patients is proposed as a cause of the reduction,[123][124] in agreement with the observations dating from the 1960s that administration of methionine to schizophrenic patients results in a profound exacerbation of schizophrenia symptoms in sixty to seventy percent of patients.[125][126][127][128] The proposed mechanism is a part of the "epigenetic hypothesis for schizophrenia pathophysiology" formulated by a group of scientists in 2008 (D. Grayson; A. Guidotti; E. Costa).[13][129] A postmortem study comparing a DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1) and Reelin mRNA expression in cortical layers I and V of schizophrenic patients and normal controls demonstrated that in the layer V both DNMT1 and Reelin levels were normal, while in the layer I DNMT1 was threefold higher, probably leading to the twofold decrease in the Reelin expression.[130] There is evidence that the change is selective, and DNMT1 is overexpressed in reelin-secreting GABAergic neurons but not in their glutamatergic neighbours.[131][132] Methylation inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as valproic acid, increase reelin mRNA levels,[133][134][135] while L-methionine treatment downregulates the phenotypic expression of reelin.[136]

One study indicated the upregulation of histone deacetylase HDAC1 in the hippocampi of patients.[137] Histone deacetylases suppress gene promoters; hyperacetylation of histones was shown in murine models to demethylate the promoters of both reelin and GAD67.[138] DNMT1 inhibitors in animals have been shown to increase the expression of both reelin and GAD67,[139] and both DNMT inhibitors and HDAC inhibitors shown in one study[140] to activate both genes with comparable dose- and time-dependence. As one study shows, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) concentration in patients' prefrontal cortex is twice as high as in the cortices of non-affected people.[141] SAM, being a methyl group donor necessary for DNMT activity, could further shift epigenetic control of gene expression.[citation needed]

Chromosome region 7q22 that harbours the RELN gene is associated with schizophrenia,[142] and the gene itself was associated with the disease in a large study that found the polymorphism rs7341475 to increase the risk of the disease in women, but not in men. The women that have the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) are about 1.4 times more likely to get ill, according to the study.[143] Allelic variations of RELN have also been correlated with working memory, memory and executive functioning in nuclear families where one of the members suffers from schizophrenia.[142] The association with working memory was later replicated.[144] In one small study, nonsynonymous polymorphism Val997Leu of the gene was associated with left and right ventricular enlargement in patients.[145]

One study showed that patients have decreased levels of one of reelin receptors, VLDLR, in the peripheral lymphocytes.[146] After six months of antipsychotic therapy the expression went up; according to authors, peripheral VLRLR levels may serve as a reliable peripheral biomarker of schizophrenia.[146]

Considering the role of reelin in promoting dendritogenesis,[9][90] suggestions were made that the localized dendritic spine deficit observed in schizophrenia[147][148] could be in part connected with the downregulation of reelin.[149][150]

Reelin pathway could also be linked to schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders through its interaction with risk genes. One example is the neuronal transcription factor NPAS3, disruption of which is linked to schizophrenia[151] and learning disability. Knockout mice lacking NPAS3 or the similar protein NPAS1 have significantly lower levels of reelin;[152] the precise mechanism behind this is unknown. Another example is the schizophrenia-linked gene MTHFR, with murine knockouts showing decreased levels of reelin in the cerebellum.[153] Along the same line, it is worth noting that the gene coding for the subunit NR2B that is presumably affected by reelin in the process of NR2B->NR2A developmental change of NMDA receptor composition,[65] stands as one of the strongest risk gene candidates.[154] Another shared aspect between NR2B and RELN is that they both can be regulated by the TBR1 transcription factor.[155]

The heterozygous reeler mouse, which is haploinsufficient for the RELN gene, shares several neurochemical and behavioral abnormalities with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,[156] but the exact relevance of these murine behavioral changes to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia remains debatable.[157]

As previously described, reelin plays a crucial role in modulating early neuroblast migration during brain development. Evidences of altered neural cell positioning in post-mortem schizophrenia patient brains[158][159] and changes to gene regulatory networks that control cell migration[160][161] suggests a potential link between altered reelin expression in patient brain tissue to disrupted cell migration during brain development. To model the role of reelin in the context of schizophrenia at a cellular level, olfactory neurosphere-derived cells were generated from the nasal biopsies of schizophrenia patients, and compared to cells from healthy controls.[160] Schizophrenia patient-derived cells have reduced levels of reelin mRNA[160] and protein[162] when compared to healthy control cells, but expresses the key reelin receptors and DAB1 accessory protein.[162] When grown in vitro, schizophrenia patient-derived cells were unable to respond to reelin coated onto tissue culture surfaces; In contrast, cells derived from healthy controls were able to alter their cell migration when exposed to reelin.[162] This work went on to show that the lack of cell migration response in patient-derived cells were caused by the cell's inability to produce enough focal adhesions of the appropriate size when in contact with extracellular reelin.[162] More research into schizophrenia cell-based models are needed to look at the function of reelin, or lack of, in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Bipolar disorder

[edit]Decrease in RELN expression with concurrent upregulation of DNMT1 is typical of bipolar disorder with psychosis, but is not characteristic of patients with major depression without psychosis, which could speak of specific association of the change with psychoses.[116] One study suggests that unlike in schizophrenia, such changes are found only in the cortex and do not affect the deeper structures in psychotic bipolar patients, as their basal ganglia were found to have the normal levels of DNMT1 and subsequently both the reelin and GAD67 levels were within the normal range.[118]

In a genetic study conducted in 2009, preliminary evidence requiring further DNA replication suggested that variation of the RELN gene (SNP rs362719) may be associated with susceptibility to bipolar disorder in women.[163]

Autism

[edit]Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is generally believed to be caused by mutations in several locations, likely triggered by environmental factors. The role of reelin in autism is not decided yet.[164]

Reelin was originally in 2001 implicated in a study finding associations between autism and a polymorphic GGC/CGG repeat preceding the 5' ATG initiator codon of the RELN gene in an Italian population. Longer triplet repeats in the 5' region were associated with an increase in autism susceptibility.[165] However, another study of 125 multiple-incidence families and 68 single-incidence families from the subsequent year found no significant difference between the length of the polymorphic repeats in affected and controls. Although, using a family based association test larger reelin alleles were found to be transmitted more frequently than expected to affected children.[166] An additional study examining 158 subjects with German lineage likewise found no evidence of triplet repeat polymorphisms associated with autism.[167] And a larger study from 2004 consisting of 395 families found no association between autistic subjects and the CGG triplet repeat as well as the allele size when compared to age of first word.[168] In 2010 a large study using data from 4 European cohorts would find some evidence for an association between autism and the rs362780 RELN polymorphism.[169]

Studies of transgenic mice have been suggestive of an association, but not definitive.[170]

Temporal lobe epilepsy: granule cell dispersion

[edit]Decreased reelin expression in the hippocampal tissue samples from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy was found to be directly correlated with the extent of granule cell dispersion (GCD), a major feature of the disease that is noted in 45%–73% of patients.[171][172] The dispersion, according to a small study, is associated with the RELN promoter hypermethylation.[173] According to one study, prolonged seizures in a rat model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy have led to the loss of reelin-expressing interneurons and subsequent ectopic chain migration and aberrant integration of newborn dentate granule cells. Without reelin, the chain-migrating neuroblasts failed to detach properly.[174] Moreover, in a kainate-induced mouse epilepsy model, exogenous reelin had prevented GCD, according to one study.[175]

Alzheimer's disease

[edit]The Reelin receptors ApoER2 and VLDLR belong to the LDL receptor gene family.[176] All members of this family are receptors for Apolipoprotein E (ApoE). Therefore, they are often synonymously referred to as 'ApoE receptors'. ApoE occurs in 3 common isoforms (E2, E3, E4) in the human population. ApoE4 is the primary genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease. This strong genetic association has led to the proposal that ApoE receptors play a central role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease.[176][177] According to one study, reelin expression and glycosylation patterns are altered in Alzheimer's disease. In the cortex of the patients, reelin levels were 40% higher compared with controls, but the cerebellar levels of the protein remain normal in the same patients.[178] This finding is in agreement with an earlier study showing the presence of Reelin associated with amyloid plaques in a transgenic AD mouse model.[179] A large genetic study of 2008 showed that RELN gene variation is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease in women.[180] The number of reelin-producing Cajal-Retzius cells is significantly decreased in the first cortical layer of patients.[181][182] Reelin has been shown to interact with amyloid precursor protein,[183] and, according to one in-vitro study, is able to counteract the Aβ-induced dampening of NMDA-receptor activity.[184] This is modulated by ApoE isoforms, which selectively alter the recycling of ApoER2 as well as AMPA and NMDA receptors.[185]

Cancer

[edit]DNA methylation patterns are often changed in tumours, and the RELN gene could be affected: according to one study, in the pancreatic cancer the expression is suppressed, along with other reelin pathway components[186] In the same study, cutting the reelin pathway in cancer cells that still expressed reelin resulted in increased motility and invasiveness. On the contrary, in prostate cancer the RELN expression is excessive and correlates with Gleason score.[187] Retinoblastoma presents another example of RELN overexpression.[188] This gene has also been seen recurrently mutated in cases of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.[189]

Other conditions

[edit]One genome-wide association study indicates a possible role for RELN gene variation in otosclerosis, an abnormal growth of bone of the middle ear.[190] In a statistical search for the genes that are differentially expressed in the brains of cerebral malaria-resistant versus cerebral malaria-susceptible mice, Delahaye et al. detected a significant upregulation of both RELN and DAB1 and speculated on possible protective effects of such over-expression.[191] In 2020, a study reported a novel variant in RELN gene (S2486G) which was associated with ankylosing spondylitis in a large family. This suggested a potential insight into the pathophysiological involvement of reelin via inflammation and osteogenesis pathways in ankylosing spondylitis, and it could broaden the horizon toward new therapeutic strategies.[192] A 2020 study from UT Southwestern Medical Center suggests circulating Reelin levels might correlate with MS severity and stages, and that lowering Reelin levels might be a novel way to treat MS.[193]

Factors affecting reelin expression

[edit]

The expression of reelin is controlled by a number of factors besides the sheer number of Cajal-Retzius cells. For example, TBR1 transcription factor regulates RELN along with other T-element-containing genes.[155] On a higher level, increased maternal care was found to correlate with reelin expression in rat pups; such correlation was reported in hippocampus[195] and in the cortex.[194] According to one report, prolonged exposure to corticosterone significantly decreased reelin expression in murine hippocampi, a finding possibly pertinent to the hypothetical role of corticosteroids in depression.[196] One small postmortem study has found increased methylation of RELN gene in the neocortex of persons past their puberty compared with those that had yet to enter the period of maturation.[197]

Psychotropic medication

[edit]As reelin is being implicated in a number of brain disorders and its expression is usually measured posthumously, assessing the possible medication effects is important.[198]

According to the epigenetic hypothesis, drugs that shift the balance in favour of demethylation have a potential to alleviate the proposed methylation-caused downregulation of RELN and GAD67. In one study, clozapine and sulpiride but not haloperidol and olanzapine were shown to increase the demethylation of both genes in mice pretreated with l-methionine.[199] Valproic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, when taken in combination with antipsychotics, is proposed to have some benefits. But there are studies conflicting the main premise of the epigenetic hypothesis, and a study by Fatemi et al. shows no increase in RELN expression by valproic acid; that indicates the need for further investigation.[citation needed]

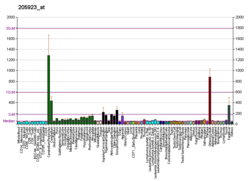

Fatemi et al. conducted the study in which RELN mRNA and reelin protein levels were measured in rat prefrontal cortex following a 21-day of intraperitoneal injections of the following drugs:[28]

| Reelin expression | Clozapine | Fluoxetine | Haloperidol | Lithium | Olanzapine | Valproic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| protein | ↓ | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↔ |

| mRNA | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

In 2009, Fatemi et al. published the more detailed work on rats using the same medication. Here, cortical expression of several participants (VLDLR, DAB1, GSK3B) of the signaling chain was measured besides reelin itself, and also the expression of GAD65 and GAD67.[200]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000189056 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000042453 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "RELN gene". Genetics Home Reference. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Bosch C, Muhaisen A, Pujadas L, Soriano E, Martínez A (2016). "Reelin Exerts Structural, Biochemical and Transcriptional Regulation Over Presynaptic and Postsynaptic Elements in the Adult Hippocampus". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 10: 138. doi:10.3389/fncel.2016.00138. PMC 4884741. PMID 27303269.

- ^ Weeber EJ, Beffert U, Jones C, Christian JM, Forster E, Sweatt JD, et al. (October 2002). "Reelin and ApoE receptors cooperate to enhance hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (42): 39944–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205147200. PMID 12167620.

- ^ a b D'Arcangelo G (August 2005). "Apoer2: a reelin receptor to remember". Neuron. 47 (4): 471–3. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.001. PMID 16102527. S2CID 15091293.

- ^ a b Niu S, Renfro A, Quattrocchi CC, Sheldon M, D'Arcangelo G (January 2004). "Reelin promotes hippocampal dendrite development through the VLDLR/ApoER2-Dab1 pathway". Neuron. 41 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00819-5. PMID 14715136. S2CID 10716252.

- ^ Niu S, Yabut O, D'Arcangelo G (October 2008). "The Reelin signaling pathway promotes dendritic spine development in hippocampal neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (41): 10339–48. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1917-08.2008. PMC 2572775. PMID 18842893.

- ^ a b "Tissue expression of RELN - Summary - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ a b Fatemi SH, Earle JA, McMenomy T (November 2000). "Reduction in Reelin immunoreactivity in hippocampus of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression". Molecular Psychiatry. 5 (6): 654–63, 571. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000783. PMID 11126396.

- ^ a b Grayson DR, Guidotti A, Costa E (17 January 2008). "Current Hypotheses". Schizophrenia Research Forum. schizophreniaforum.org. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ Tochigi M, Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Komori A, Sasaki T, Kato N, et al. (March 2008). "Methylation status of the reelin promoter region in the brain of schizophrenic patients". Biological Psychiatry. 63 (5): 530–3. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.003. PMID 17870056. S2CID 11816759.

- ^ Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, et al. (March 2008). "Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (3): 696–711. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. PMC 2427301. PMID 18319075.

- ^ Kovács KA (December 2021). "Relevance of a Novel Circuit-Level Model of Episodic Memories to Alzheimer's Disease". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (1): 462. doi:10.3390/ijms23010462. PMC 8745479. PMID 35008886.

- ^ a b Falconer DS (January 1951). "Two new mutants, 'trembler' and 'reeler', with neurological actions in the house mouse (Mus musculus L.)" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 50 (2): 192–201. doi:10.1007/BF02996215. PMID 24539699. S2CID 37918631.

- ^ Tueting P, Doueiri MS, Guidotti A, Davis JM, Costa E (2006). "Reelin down-regulation in mice and psychosis endophenotypes". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 30 (8): 1065–77. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.04.001. PMID 16769115. S2CID 21156214.

- ^ Hamburgh M (October 1963). "Analysis of the postnatal developmental effects of "reeler," a neurological mutation in mice. A study in developmental genetics". Developmental Biology. 8 (2): 165–85. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(63)90040-X. PMID 14069672.

- ^ Caviness VS (December 1976). "Patterns of cell and fiber distribution in the neocortex of the reeler mutant mouse". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 170 (4): 435–47. doi:10.1002/cne.901700404. PMID 1002868. S2CID 34383977.

- ^ Miao GG, Smeyne RJ, D'Arcangelo G, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Morgan JI, et al. (November 1994). "Isolation of an allele of reeler by insertional mutagenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (23): 11050–4. Bibcode:1994PNAS...9111050M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.23.11050. PMC 45164. PMID 7972007.

- ^ D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T (April 1995). "A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler". Nature. 374 (6524): 719–23. Bibcode:1995Natur.374..719D. doi:10.1038/374719a0. PMID 7715726. S2CID 4266946.

- ^ Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, Yagyu K, Seike M, Ikenaka K, et al. (May 1995). "The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons". Neuron. 14 (5): 899–912. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. PMID 7748558. S2CID 17993812.

- ^ Trommsdorff M, Borg JP, Margolis B, Herz J (December 1998). "Interaction of cytosolic adaptor proteins with neuronal apolipoprotein E receptors and the amyloid precursor protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (50): 33556–60. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.50.33556. PMID 9837937.

- ^ Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, Shelton J, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, et al. (June 1999). "Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2". Cell. 97 (6): 689–701. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80782-5. PMID 10380922. S2CID 13492626.

- ^ Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, Yoneshima H, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K, et al. (October 1997). "Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice". Nature. 389 (6652): 730–3. Bibcode:1997Natur.389..730S. doi:10.1038/39601. PMID 9338784. S2CID 4414738.

- ^ "Reelin" mentioned in the titles of scientific literature – a search in the Google Scholar

- ^ a b c d e Hossein S. Fatemi, ed. (2008). Reelin Glycoprotein: Structure, Biology and Roles in Health and Disease. Springer. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-387-76760-4.

- ^ Lacor PN, Grayson DR, Auta J, Sugaya I, Costa E, Guidotti A (March 2000). "Reelin secretion from glutamatergic neurons in culture is independent from neurotransmitter regulation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (7): 3556–61. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.3556L. doi:10.1073/pnas.050589597. PMC 16278. PMID 10725375.

- ^ Meyer G, Goffinet AM, Fairén A (December 1999). "What is a Cajal-Retzius cell? A reassessment of a classical cell type based on recent observations in the developing neocortex". Cerebral Cortex. 9 (8): 765–75. doi:10.1093/cercor/9.8.765. PMID 10600995.

- ^ a b Meyer G, Goffinet AM (July 1998). "Prenatal development of reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the human neocortex". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 397 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980720)397:1<29::AID-CNE3>3.3.CO;2-7. PMID 9671277.

- ^ Schiffmann SN, Bernier B, Goffinet AM (May 1997). "Reelin mRNA expression during mouse brain development". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 9 (5): 1055–71. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01456.x. PMID 9182958. S2CID 22576790.

- ^ Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG, Uzunov DP, Costa E, Guidotti A, et al. (March 1998). "Reelin is preferentially expressed in neurons synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in cortex and hippocampus of adult rats". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (6): 3221–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.3221P. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.6.3221. PMC 19723. PMID 9501244.

- ^ Kovács KA (September 2020). "Episodic Memories: How do the Hippocampus and the Entorhinal Ring Attractors Cooperate to Create Them?". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 14: 68. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2020.559186. PMC 7511719. PMID 33013334.

- ^ Alcántara S, Ruiz M, D'Arcangelo G, Ezan F, de Lecea L, Curran T, et al. (October 1998). "Regional and cellular patterns of reelin mRNA expression in the forebrain of the developing and adult mouse". The Journal of Neuroscience. 18 (19): 7779–99. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07779.1998. PMC 6792998. PMID 9742148.

- ^ Pesold C, Liu WS, Guidotti A, Costa E, Caruncho HJ (March 1999). "Cortical bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells preferentially express and secrete reelin into perineuronal nets, nonsynaptically modulating gene expression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (6): 3217–22. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.3217P. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.6.3217. PMC 15922. PMID 10077664.

- ^ Suárez-Solá ML, González-Delgado FJ, Pueyo-Morlans M, Medina-Bolívar OC, Hernández-Acosta NC, González-Gómez M, et al. (2009). "Neurons in the white matter of the adult human neocortex". Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 3: 7. doi:10.3389/neuro.05.007.2009. PMC 2697018. PMID 19543540.

- ^ Smalheiser NR, Costa E, Guidotti A, Impagnatiello F, Auta J, Lacor P, et al. (February 2000). "Expression of reelin in adult mammalian blood, liver, pituitary pars intermedia, and adrenal chromaffin cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (3): 1281–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1281S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.3.1281. PMC 15597. PMID 10655522.

- ^ Samama B, Boehm N (July 2005). "Reelin immunoreactivity in lymphatics and liver during development and adult life". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 285 (1): 595–9. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20202. PMID 15912522.

- ^ a b Kobold D, Grundmann A, Piscaglia F, Eisenbach C, Neubauer K, Steffgen J, et al. (May 2002). "Expression of reelin in hepatic stellate cells and during hepatic tissue repair: a novel marker for the differentiation of HSC from other liver myofibroblasts". Journal of Hepatology. 36 (5): 607–13. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00050-8. PMID 11983443.

- ^ a b Pulido JS, Sugaya I, Comstock J, Sugaya K (June 2007). "Reelin expression is upregulated following ocular tissue injury". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 245 (6): 889–93. doi:10.1007/s00417-006-0458-4. PMID 17120005. S2CID 12397364.

- ^ Buchaille R, Couble ML, Magloire H, Bleicher F (September 2000). "A substractive PCR-based cDNA library from human odontoblast cells: identification of novel genes expressed in tooth forming cells". Matrix Biology. 19 (5): 421–30. doi:10.1016/S0945-053X(00)00091-3. PMID 10980418.

- ^ Allard B, Magloire H, Couble ML, Maurin JC, Bleicher F (September 2006). "Voltage-gated sodium channels confer excitability to human odontoblasts: possible role in tooth pain transmission". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (39): 29002–10. doi:10.1074/jbc.M601020200. PMID 16831873.

- ^ Maurin JC, Couble ML, Didier-Bazes M, Brisson C, Magloire H, Bleicher F (August 2004). "Expression and localization of reelin in human odontoblasts". Matrix Biology. 23 (5): 277–85. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2004.06.005. PMID 15464360.

- ^ PDB: 2E26; Yasui N, Nogi T, Kitao T, Nakano Y, Hattori M, Takagi J (June 2007). "Structure of a receptor-binding fragment of reelin and mutational analysis reveal a recognition mechanism similar to endocytic receptors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (24): 9988–93. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9988Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700438104. PMC 1891246. PMID 17548821.

- ^ a b Quattrocchi CC, Wannenes F, Persico AM, Ciafré SA, D'Arcangelo G, Farace MG, et al. (January 2002). "Reelin is a serine protease of the extracellular matrix". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (1): 303–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106996200. hdl:11380/1250927. PMID 11689558.

- ^ a b Royaux I, Lambert de Rouvroit C, D'Arcangelo G, Demirov D, Goffinet AM (December 1997). "Genomic organization of the mouse reelin gene". Genomics. 46 (2): 240–50. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.4983. PMID 9417911.

- ^ PDB: 2ddu; Nogi T, Yasui N, Hattori M, Iwasaki K, Takagi J (August 2006). "Structure of a signaling-competent reelin fragment revealed by X-ray crystallography and electron tomography". The EMBO Journal. 25 (15): 3675–83. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601240. PMC 1538547. PMID 16858396.

- ^ Nakano Y, Kohno T, Hibi T, Kohno S, Baba A, Mikoshiba K, et al. (July 2007). "The extremely conserved C-terminal region of Reelin is not necessary for secretion but is required for efficient activation of downstream signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (28): 20544–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702300200. PMID 17504759.

- ^ Lambert de Rouvroit C, de Bergeyck V, Cortvrindt C, Bar I, Eeckhout Y, Goffinet AM (March 1999). "Reelin, the extracellular matrix protein deficient in reeler mutant mice, is processed by a metalloproteinase". Experimental Neurology. 156 (1): 214–7. doi:10.1006/exnr.1998.7007. PMID 10192793. S2CID 35222830.

- ^ a b c Jossin Y, Ignatova N, Hiesberger T, Herz J, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM (January 2004). "The central fragment of Reelin, generated by proteolytic processing in vivo, is critical to its function during cortical plate development". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (2): 514–21. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-03.2004. PMC 6730001. PMID 14724251.

- ^ a b c Jossin Y, Gui L, Goffinet AM (April 2007). "Processing of Reelin by embryonic neurons is important for function in tissue but not in dissociated cultured neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (16): 4243–52. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0023-07.2007. PMC 6672330. PMID 17442808.

- ^ a b Blake SM, Strasser V, Andrade N, Duit S, Hofbauer R, Schneider WJ, et al. (November 2008). "Thrombospondin-1 binds to ApoER2 and VLDL receptor and functions in postnatal neuronal migration". The EMBO Journal. 27 (22): 3069–80. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.223. PMC 2585172. PMID 18946489.

- ^ Lennington JB, Yang Z, Conover JC (November 2003). "Neural stem cells and the regulation of adult neurogenesis". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 1: 99. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-1-99. PMC 293430. PMID 14614786.

- ^ a b Hartfuss E, Förster E, Bock HH, Hack MA, Leprince P, Luque JM, et al. (October 2003). "Reelin signaling directly affects radial glia morphology and biochemical maturation". Development. 130 (19): 4597–609. doi:10.1242/dev.00654. hdl:10261/333510. PMID 12925587.

- ^ a b c d e Nomura T, Takahashi M, Hara Y, Osumi N (January 2008). Reh T (ed.). "Patterns of neurogenesis and amplitude of Reelin expression are essential for making a mammalian-type cortex". PLOS ONE. 3 (1) e1454. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1454N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001454. PMC 2175532. PMID 18197264.

- ^ Del Río JA, Heimrich B, Borrell V, Förster E, Drakew A, Alcántara S, et al. (January 1997). "A role for Cajal-Retzius cells and reelin in the development of hippocampal connections". Nature. 385 (6611): 70–4. Bibcode:1997Natur.385...70D. doi:10.1038/385070a0. PMID 8985248. S2CID 4352996.

- ^ Borrell V, Del Río JA, Alcántara S, Derer M, Martínez A, D'Arcangelo G, et al. (February 1999). "Reelin regulates the development and synaptogenesis of the layer-specific entorhino-hippocampal connections". The Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (4): 1345–58. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01345.1999. PMC 6786030. PMID 9952412.

- ^ a b Hack I, Bancila M, Loulier K, Carroll P, Cremer H (October 2002). "Reelin is a detachment signal in tangential chain-migration during postnatal neurogenesis". Nature Neuroscience. 5 (10): 939–45. doi:10.1038/nn923. PMID 12244323. S2CID 7096018.

- ^ a b c Yoshida M, Assimacopoulos S, Jones KR, Grove EA (February 2006). "Massive loss of Cajal-Retzius cells does not disrupt neocortical layer order". Development. 133 (3): 537–45. doi:10.1242/dev.02209. PMID 16410414. S2CID 1702450.

- ^ Yip YP, Mehta N, Magdaleno S, Curran T, Yip JW (July 2009). "Ectopic expression of reelin alters migration of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 515 (2): 260–8. doi:10.1002/cne.22044. PMID 19412957. S2CID 21832778.

- ^ a b Campo CG, Sinagra M, Verrier D, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P (2009). Okazawa H (ed.). "Reelin secreted by GABAergic neurons regulates glutamate receptor homeostasis". PLOS ONE. 4 (5) e5505. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5505C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005505. PMC 2675077. PMID 19430527.

- ^ INSERM – Olivier Manzoni – Physiopathology of Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity Archived 25 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine – Bordo neuroscience institute.

- ^ Sinagra M, Verrier D, Frankova D, Korwek KM, Blahos J, Weeber EJ, et al. (June 2005). "Reelin, very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 control somatic NMDA receptor composition during hippocampal maturation in vitro". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (26): 6127–36. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1757-05.2005. PMC 6725049. PMID 15987942.

- ^ a b Groc L, Choquet D, Stephenson FA, Verrier D, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P (September 2007). "NMDA receptor surface trafficking and synaptic subunit composition are developmentally regulated by the extracellular matrix protein Reelin". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (38): 10165–75. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1772-07.2007. PMC 6672660. PMID 17881522.

- ^ Liu XB, Murray KD, Jones EG (October 2004). "Switching of NMDA receptor 2A and 2B subunits at thalamic and cortical synapses during early postnatal development". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (40): 8885–95. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2476-04.2004. PMC 6729956. PMID 15470155.

- ^ Andrade N, Komnenovic V, Blake SM, Jossin Y, Howell B, Goffinet A, et al. (May 2007). "ApoER2/VLDL receptor and Dab1 in the rostral migratory stream function in postnatal neuronal migration independently of Reelin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (20): 8508–13. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8508A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611391104. PMC 1895980. PMID 17494763.

- ^ Frotscher M, Haas CA, Förster E (June 2003). "Reelin controls granule cell migration in the dentate gyrus by acting on the radial glial scaffold". Cerebral Cortex. 13 (6): 634–40. doi:10.1093/cercor/13.6.634. PMID 12764039.

- ^ Bar I, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Goffinet AM (December 2000). "The evolution of cortical development. An hypothesis based on the role of the Reelin signaling pathway". Trends in Neurosciences. 23 (12): 633–8. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01675-1. PMID 11137154. S2CID 13568642.

- ^ Molnár Z, Métin C, Stoykova A, Tarabykin V, Price DJ, Francis F, et al. (February 2006). "Comparative aspects of cerebral cortical development". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (4): 921–34. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04611.x. PMC 1931431. PMID 16519657.

- ^ a b Pérez-García CG, González-Delgado FJ, Suárez-Solá ML, Castro-Fuentes R, Martín-Trujillo JM, Ferres-Torres R, et al. (January 2001). "Reelin-immunoreactive neurons in the adult vertebrate pallium". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 21 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00104-6. PMID 11173219. S2CID 23395046.

- ^ Costagli A, Kapsimali M, Wilson SW, Mione M (August 2002). "Conserved and divergent patterns of Reelin expression in the zebrafish central nervous system". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 450 (1): 73–93. doi:10.1002/cne.10292. PMID 12124768. S2CID 23110916.

- ^ Goffinet AM (November 2006). "What makes us human? A biased view from the perspective of comparative embryology and mouse genetics". Journal of Biomedical Discovery and Collaboration. 1: 16. doi:10.1186/1747-5333-1-16. PMC 1769396. PMID 17132178.

- ^ Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, Lambot MA, Coppens S, Pedersen JS, et al. (September 2006). "An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans" (PDF). Nature. 443 (7108): 167–72. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..167P. doi:10.1038/nature05113. PMID 16915236. S2CID 18107797.

- ^ Williamson SH, Hubisz MJ, Clark AG, Payseur BA, Bustamante CD, Nielsen R (June 2007). "Localizing recent adaptive evolution in the human genome". PLOS Genetics. 3 (6) e90. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030090. PMC 1885279. PMID 17542651.

- ^ Wade N (26 June 2007). "Humans Have Spread Globally, and Evolved Locally". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ a b Zhang G, Assadi AH, McNeil RS, Beffert U, Wynshaw-Boris A, Herz J, et al. (February 2007). Mueller U (ed.). "The Pafah1b complex interacts with the reelin receptor VLDLR". PLOS ONE. 2 (2) e252. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..252Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000252. PMC 1800349. PMID 17330141.

- ^ D'Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T (October 1999). "Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors". Neuron. 24 (2): 471–9. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80860-0. PMID 10571240. S2CID 14631418.

- ^ Hiesberger T, Trommsdorff M, Howell BW, Goffinet A, Mumby MC, Cooper JA, et al. (October 1999). "Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation". Neuron. 24 (2): 481–9. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80861-2. PMID 10571241. S2CID 243043.

- ^ Andersen OM, Benhayon D, Curran T, Willnow TE (August 2003). "Differential binding of ligands to the apolipoprotein E receptor 2". Biochemistry. 42 (31): 9355–64. doi:10.1021/bi034475p. PMID 12899622.

- ^ Benhayon D, Magdaleno S, Curran T (April 2003). "Binding of purified Reelin to ApoER2 and VLDLR mediates tyrosine phosphorylation of Disabled-1". Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 112 (1–2): 33–45. doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00032-9. PMID 12670700.

- ^ Hack I, Hellwig S, Junghans D, Brunne B, Bock HH, Zhao S, et al. (November 2007). "Divergent roles of ApoER2 and Vldlr in the migration of cortical neurons". Development. 134 (21): 3883–91. doi:10.1242/dev.005447. PMID 17913789.

- ^ Schmid RS, Jo R, Shelton S, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES (October 2005). "Reelin, integrin and DAB1 interactions during embryonic cerebral cortical development". Cerebral Cortex. 15 (10): 1632–6. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi041. PMID 15703255.

- ^ Senzaki K, Ogawa M, Yagi T (December 1999). "Proteins of the CNR family are multiple receptors for Reelin". Cell. 99 (6): 635–47. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81552-4. PMID 10612399. S2CID 14277878.

- ^ Hibi T, Hattori M (April 2009). "The N-terminal fragment of Reelin is generated after endocytosis and released through the pathway regulated by Rab11". FEBS Letters. 583 (8): 1299–303. Bibcode:2009FEBSL.583.1299H. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.024. PMID 19303411. S2CID 43542615.

- ^ Chameau P, Inta D, Vitalis T, Monyer H, Wadman WJ, van Hooft JA (April 2009). "The N-terminal region of reelin regulates postnatal dendritic maturation of cortical pyramidal neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (17): 7227–32. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7227C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810764106. PMC 2678467. PMID 19366679.

- ^ Belvindrah R, Graus-Porta D, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Müller U (December 2007). "Beta1 integrins in radial glia but not in migrating neurons are essential for the formation of cell layers in the cerebral cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (50): 13854–65. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4494-07.2007. PMC 6673609. PMID 18077697.

- ^ Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Durudas A, Qiu S, Masiulis I, Sweatt JD, et al. (August 2005). "Modulation of synaptic plasticity and memory by Reelin involves differential splicing of the lipoprotein receptor Apoer2". Neuron. 47 (4): 567–79. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.007. PMID 16102539. S2CID 5854936.

- ^ Miller CA, Sweatt JD (March 2007). "Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation". Neuron. 53 (6): 857–69. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022. PMID 17359920. S2CID 62791264.

- ^ a b Matsuki T, Pramatarova A, Howell BW (June 2008). "Reduction of Crk and CrkL expression blocks reelin-induced dendritogenesis". Journal of Cell Science. 121 (11): 1869–75. doi:10.1242/jcs.027334. PMC 2430739. PMID 18477607.

- ^ Ballif BA, Arnaud L, Arthur WT, Guris D, Imamoto A, Cooper JA (April 2004). "Activation of a Dab1/CrkL/C3G/Rap1 pathway in Reelin-stimulated neurons". Current Biology. 14 (7): 606–10. Bibcode:2004CBio...14..606B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.038. PMID 15062102. S2CID 52887334.

- ^ Park TJ, Curran T (December 2008). "Crk and Crk-like play essential overlapping roles downstream of disabled-1 in the Reelin pathway". The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (50): 13551–62. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-08.2008. PMC 2628718. PMID 19074029.

- ^ a b Keilani S, Sugaya K (July 2008). "Reelin induces a radial glial phenotype in human neural progenitor cells by activation of Notch-1". BMC Developmental Biology. 8 (1): 69. doi:10.1186/1471-213X-8-69. PMC 2447831. PMID 18593473.

- ^ Lugli G, Krueger JM, Davis JM, Persico AM, Keller F, Smalheiser NR (September 2003). "Methodological factors influencing measurement and processing of plasma reelin in humans". BMC Biochemistry. 4: 9. doi:10.1186/1471-2091-4-9. PMC 200967. PMID 12959647.

- ^ Howell BW, Gertler FB, Cooper JA (January 1997). "Mouse disabled (mDab1): a Src binding protein implicated in neuronal development". The EMBO Journal. 16 (1): 121–32. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.1.121. PMC 1169619. PMID 9009273.

- ^ Arnaud L, Ballif BA, Förster E, Cooper JA (January 2003). "Fyn tyrosine kinase is a critical regulator of disabled-1 during brain development". Current Biology. 13 (1): 9–17. Bibcode:2003CBio...13....9A. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01397-0. PMID 12526739. S2CID 1739505.

- ^ Feng L, Allen NS, Simo S, Cooper JA (November 2007). "Cullin 5 regulates Dab1 protein levels and neuron positioning during cortical development". Genes & Development. 21 (21): 2717–30. doi:10.1101/gad.1604207. PMC 2045127. PMID 17974915.

- ^ Kerjan G, Gleeson JG (November 2007). "A missed exit: Reelin sets in motion Dab1 polyubiquitination to put the break on neuronal migration". Genes & Development. 21 (22): 2850–4. doi:10.1101/gad.1622907. PMID 18006681.

- ^ Utsunomiya-Tate N, Kubo K, Tate S, Kainosho M, Katayama E, Nakajima K, et al. (August 2000). "Reelin molecules assemble together to form a large protein complex, which is inhibited by the function-blocking CR-50 antibody". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (17): 9729–34. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.9729U. doi:10.1073/pnas.160272497. PMC 16933. PMID 10920200.

- ^ Kubo K, Mikoshiba K, Nakajima K (August 2002). "Secreted Reelin molecules form homodimers". Neuroscience Research. 43 (4): 381–8. doi:10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00068-8. PMID 12135781. S2CID 10656560.

- ^ a b Strasser V, Fasching D, Hauser C, Mayer H, Bock HH, Hiesberger T, et al. (February 2004). "Receptor clustering is involved in Reelin signaling". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (3): 1378–86. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.3.1378-1386.2004. PMC 321426. PMID 14729980.

- ^ Chai X, Förster E, Zhao S, Bock HH, Frotscher M (January 2009). "Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (1): 288–99. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2934-08.2009. PMC 6664910. PMID 19129405.

- ^ Frotscher M, Chai X, Bock HH, Haas CA, Förster E, Zhao S (November 2009). "Role of Reelin in the development and maintenance of cortical lamination". Journal of Neural Transmission. 116 (11): 1451–5. doi:10.1007/s00702-009-0228-7. PMID 19396394. S2CID 1310387.

- ^ Arnaud L, Ballif BA, Cooper JA (December 2003). "Regulation of protein tyrosine kinase signaling by substrate degradation during brain development". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (24): 9293–302. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.24.9293-9302.2003. PMC 309695. PMID 14645539.

- ^ Ohshima T, Suzuki H, Morimura T, Ogawa M, Mikoshiba K (April 2007). "Modulation of Reelin signaling by Cyclin-dependent kinase 5". Brain Research. 1140: 84–95. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.121. PMID 16529723. S2CID 23991327.

- ^ Keshvara L, Magdaleno S, Benhayon D, Curran T (June 2002). "Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates disabled 1 independently of Reelin signaling". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (12): 4869–77. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04869.2002. PMC 6757745. PMID 12077184.

- ^ Kobayashi S, Ishiguro K, Omori A, Takamatsu M, Arioka M, Imahori K, et al. (December 1993). "A cdc2-related kinase PSSALRE/cdk5 is homologous with the 30 kDa subunit of tau protein kinase II, a proline-directed protein kinase associated with microtubule". FEBS Letters. 335 (2): 171–5. Bibcode:1993FEBSL.335..171K. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)80723-8. PMID 8253190. S2CID 26474408.

- ^ Beffert U, Morfini G, Bock HH, Reyna H, Brady ST, Herz J (December 2002). "Reelin-mediated signaling locally regulates protein kinase B/Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (51): 49958–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.M209205200. PMID 12376533.

- ^ Sasaki S, Shionoya A, Ishida M, Gambello MJ, Yingling J, Wynshaw-Boris A, et al. (December 2000). "A LIS1/NUDEL/cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain complex in the developing and adult nervous system". Neuron. 28 (3): 681–96. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00146-X. PMID 11163259. S2CID 17738599.

- ^ a b Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Morfini G, Ko J, Brady ST, Tsai LH, et al. (February 2004). "Reelin and cyclin-dependent kinase 5-dependent signals cooperate in regulating neuronal migration and synaptic transmission". The Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (8): 1897–906. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4084-03.2004. PMC 6730409. PMID 14985430.

- ^ Ohshima T, Ogawa M, Hirasawa M, Longenecker G, Ishiguro K, Pant HC, et al. (February 2001). "Synergistic contributions of cyclin-dependant kinase 5/p35 and Reelin/Dab1 to the positioning of cortical neurons in the developing mouse brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (5): 2764–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.2764O. doi:10.1073/pnas.051628498. PMC 30213. PMID 11226314.

- ^ Hong SE, Shugart YY, Huang DT, Shahwan SA, Grant PE, Hourihane JO, et al. (September 2000). "Autosomal recessive lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia is associated with human RELN mutations". Nature Genetics. 26 (1): 93–6. doi:10.1038/79246. PMID 10973257. S2CID 67748801.

- ^ Crino P (November 2001). "New RELN Mutation Associated with Lissencephaly and Epilepsy". Epilepsy Currents. 1 (2): 72–73. doi:10.1046/j.1535-7597.2001.00017.x. PMC 320825. PMID 15309195.

- ^ Zaki M, Shehab M, El-Aleem AA, Abdel-Salam G, Koeller HB, Ilkin Y, et al. (May 2007). "Identification of a novel recessive RELN mutation using a homozygous balanced reciprocal translocation". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 143A (9): 939–44. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31667. PMID 17431900. S2CID 19126812.

- ^ Impagnatiello F, Guidotti AR, Pesold C, Dwivedi Y, Caruncho H, Pisu MG, et al. (December 1998). "A decrease of reelin expression as a putative vulnerability factor in schizophrenia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (26): 15718–23. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9515718I. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15718. PMC 28110. PMID 9861036.

- ^ a b Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Di-Giorgi-Gerevini V, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, et al. (November 2000). "Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 57 (11): 1061–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. PMID 11074872.

- ^ a b Fatemi SH, Hossein Fatemi S, Stary JM, Earle JA, Araghi-Niknam M, Eagan E (January 2005). "GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders as reflected by decreased levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa and Reelin proteins in cerebellum". Schizophrenia Research. 72 (2–3): 109–22. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.017. PMID 15560956. S2CID 35193802.

- ^ a b Veldic M, Kadriu B, Maloku E, Agis-Balboa RC, Guidotti A, Davis JM, et al. (March 2007). "Epigenetic mechanisms expressed in basal ganglia GABAergic neurons differentiate schizophrenia from bipolar disorder". Schizophrenia Research. 91 (1–3): 51–61. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.029. PMC 1876737. PMID 17270400.

- ^ Eastwood SL, Harrison PJ (September 2003). "Interstitial white matter neurons express less reelin and are abnormally distributed in schizophrenia: towards an integration of molecular and morphologic aspects of the neurodevelopmental hypothesis". Molecular Psychiatry. 8 (9): 769, 821–31. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001371. PMID 12931209. S2CID 25020557.

- ^ Abdolmaleky HM, Cheng KH, Russo A, Smith CL, Faraone SV, Wilcox M, et al. (April 2005). "Hypermethylation of the reelin (RELN) promoter in the brain of schizophrenic patients: a preliminary report". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 134B (1): 60–6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30140. PMID 15717292. S2CID 23169492.

- ^ Fatemi SH, Kroll JL, Stary JM (October 2001). "Altered levels of Reelin and its isoforms in schizophrenia and mood disorders". NeuroReport. 12 (15): 3209–15. doi:10.1097/00001756-200110290-00014. PMID 11711858. S2CID 43077109.

- ^ Knable MB, Torrey EF, Webster MJ, Bartko JJ (July 2001). "Multivariate analysis of prefrontal cortical data from the Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortium". Brain Research Bulletin. 55 (5): 651–9. doi:10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00521-4. PMID 11576762. S2CID 23427111.

- ^ Grayson DR, Jia X, Chen Y, Sharma RP, Mitchell CP, Guidotti A, et al. (June 2005). "Reelin promoter hypermethylation in schizophrenia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (26): 9341–6. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9341G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503736102. PMC 1166626. PMID 15961543.

- ^ Dong E, Agis-Balboa RC, Simonini MV, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A (August 2005). "Reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 promoter remodeling in an epigenetic methionine-induced mouse model of schizophrenia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (35): 12578–83. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10212578D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505394102. PMC 1194936. PMID 16113080.

- ^ Pollin W, Cardon PV, Kety SS (January 1961). "Effects of amino acid feedings in schizophrenic patients treated with iproniazid". Science. 133 (3446): 104–5. Bibcode:1961Sci...133..104P. doi:10.1126/science.133.3446.104. PMID 13736870. S2CID 32080078.

- ^ Brune GG, Himwich HE (May 1962). "Effects of methionine loading on the behavior of schizophrenic patients". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 134 (5): 447–50. doi:10.1097/00005053-196205000-00007. PMID 13873983. S2CID 46617457.

- ^ Park LC, Baldessarini RJ, Kety SS (April 1965). "Methionine Effects on Chronic Schizophrenics". Archives of General Psychiatry. 12 (4): 346–51. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720340018003. PMID 14258360.

- ^ Antun FT, Burnett GB, Cooper AJ, Daly RJ, Smythies JR, Zealley AK (June 1971). "The effects of L-methionine (without MAOI) in schizophrenia". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 8 (2): 63–71. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(71)90009-4. PMID 4932991.

- ^ Grayson DR, Chen Y, Dong E, Kundakovic M, Guidotti A (April 2009). "From trans-methylation to cytosine methylation: evolution of the methylation hypothesis of schizophrenia". Epigenetics. 4 (3): 144–9. doi:10.4161/epi.4.3.8534. PMID 19395859.

- ^ Ruzicka WB, Zhubi A, Veldic M, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A (April 2007). "Selective epigenetic alteration of layer I GABAergic neurons isolated from prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients using laser-assisted microdissection". Molecular Psychiatry. 12 (4): 385–97. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001954. PMID 17264840. S2CID 24045153.

- ^ Veldic M, Caruncho HJ, Liu WS, Davis J, Satta R, Grayson DR, et al. (January 2004). "DNA-methyltransferase 1 mRNA is selectively overexpressed in telencephalic GABAergic interneurons of schizophrenia brains". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (1): 348–53. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101..348V. doi:10.1073/pnas.2637013100. PMC 314188. PMID 14684836.

- ^ Veldic M, Guidotti A, Maloku E, Davis JM, Costa E (February 2005). "In psychosis, cortical interneurons overexpress DNA-methyltransferase 1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (6): 2152–7. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.2152V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409665102. PMC 548582. PMID 15684088.

- ^ Tremolizzo L, Doueiri MS, Dong E, Grayson DR, Davis J, Pinna G, et al. (March 2005). "Valproate corrects the schizophrenia-like epigenetic behavioral modifications induced by methionine in mice". Biological Psychiatry. 57 (5): 500–9. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.046. PMID 15737665. S2CID 29868395.

- ^ Chen Y, Sharma RP, Costa RH, Costa E, Grayson DR (July 2002). "On the epigenetic regulation of the human reelin promoter". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (13): 2930–9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf401. PMC 117056. PMID 12087179.

- ^ Mitchell CP, Chen Y, Kundakovic M, Costa E, Grayson DR (April 2005). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease reelin promoter methylation in vitro". Journal of Neurochemistry. 93 (2): 483–92. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03040.x. PMID 15816871. S2CID 12445076.

- ^ Tremolizzo L, Carboni G, Ruzicka WB, Mitchell CP, Sugaya I, Tueting P, et al. (December 2002). "An epigenetic mouse model for molecular and behavioral neuropathologies related to schizophrenia vulnerability". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (26): 17095–100. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9917095T. doi:10.1073/pnas.262658999. PMC 139275. PMID 12481028.