Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Kerriidae.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kerriidae

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Kerriidae | |

|---|---|

| |

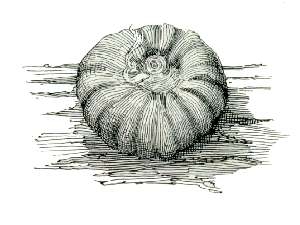

| rosette lac scale (Paratachardina decorella) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Sternorrhyncha |

| Superfamily: | Coccoidea |

| Family: | Kerriidae Lindinger, 1937 |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Kerridae | |

Kerriidae is a family of scale insects,[2] commonly known as lac insects or lac scales, erected by Karl Lindinger in 1937.

Some members of the genera Metatachardia, Tachardiella, Austrotacharidia, Afrotachardina, Tachardina, and Kerria are raised for commercial purposes, though the most commonly cultivated species is Kerria lacca. These insects secrete a waxy resin that is harvested and converted commercially into lac and shellac, used in various dyes, cosmetics, food glazes, wood finishing varnishes and polishes.[citation needed]

Commercilly-used species include:

- Kerria lacca – true lac scale

- Paratachardina decorella – rosette lac scale

- Paratachardina pseudolobata – lobate lac scale

Genera

[edit]The Global Biodiversity Information Facility[1] lists:

- Afrotachardina Chamberlin, 1923

- Albotachardina Zhang, 1992

- Austrotachardia Chamberlin, 1923

- Austrotachardiella Chamberlin, 1923

- Kerria Targioni-Tozzetti, 1884 - type genus

- Laccifer Oken, 1815

- Metatachardia Chamberlin, 1923

- Paratachardina Balachowsky, 1950

- Tachardia Blanchard, 1886

- Tachardiella Cockerell, 1901

- Tachardina Cockerell, 1901

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Global Biodiversity Information Facility: family Keriidae (retrieved 19 July 2025)

- ^ Ben-Dov, Yair; et al. (Miller, Douglass R.; Gibson, Gary A. P.) (2006). A Systematic Catalogue of Eight Scale Insect Families (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) of The World. Elsevier Science. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-444-52836-0.

External links

[edit]Kerriidae

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia